Quote and image of the month 12.2018

Richard Law, UTC 2018-12-01 07:32

Christmas is coming. The season of goodwill. Time, therefore, to take a white-knuckle ride at grump-factor 10!

Image of the month 1: The Dresden Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617-1682) is one of this website's least favourite painters (putting it kindly): his works are often ill-conceived, unstructured and shoddily executed. Unfortunately, he was also immensely productive, with many imitators, so the tosh – original and fake – gets everywhere.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Self Portrait, c. 1670. Image: ©National Gallery, London.

Art experts, who make a living from hyperbole and cant, and museums, art galleries and collectors who own the stuff, all have vested interests in the inflation of Murillo's reputation. The common phrase 'his late period', hinting at maturity, defines the years when Murillo was churning out paintings that were slapdash and barely met the criteria for the word 'finished'.

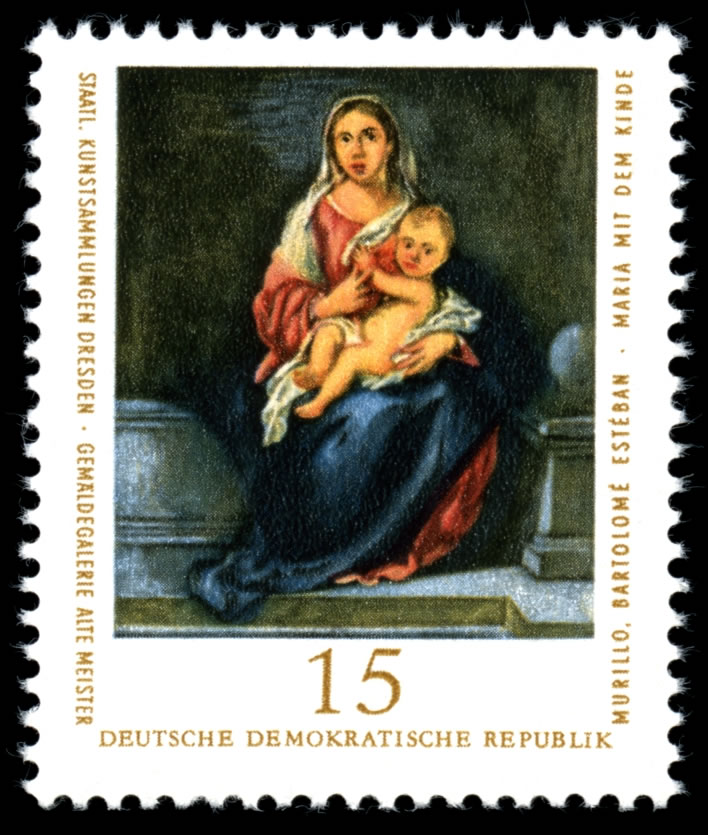

Here is one of those late works, his Maria mit dem Kind (1670-80), in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. Maria mit dem Kind, 'Mary with the Child', c.1670-80. Image: Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. [Click to open a larger version in a new tab.]

This is just one of the 43 paintings of the Virgin and Child listed in Paul Lefort's Murillo et ses Élèves suivi du Catalogue raisonné de ses Principaux ouvrages from 1892. This painting is titled in Lefort as La Vierge au chapelet avec l'Enfant, there are however so many Murillos on this theme that one runs out of unique permutations of 'Virgin' and 'Child'.

After two centuries of Protestantism and nearly 50 years under its Communist masters in the officially atheist German Democratic Republic, the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden titles it simply and atheistically: Maria mit dem Kind, 'Mary with the Child'. Which 'Mary' and which 'Child' is for the observer to guess.

The painting is not unpleasant. There is a brave lack of extraneous clutter. The scary expression of the strange man-baby on her lap is not to everyone's taste: a wide-eyed stare at the viewer whilst grasping at Mary's bosom as if to say – hey, look what I've got! The task of giving babies expressions that are imports of what is to come or which reflect some inner divinity is probably impossible. Is this baby looking out on a hostile world and reaching for its mother in fear? Is the expression on his face fright or beatitude? Who knows?

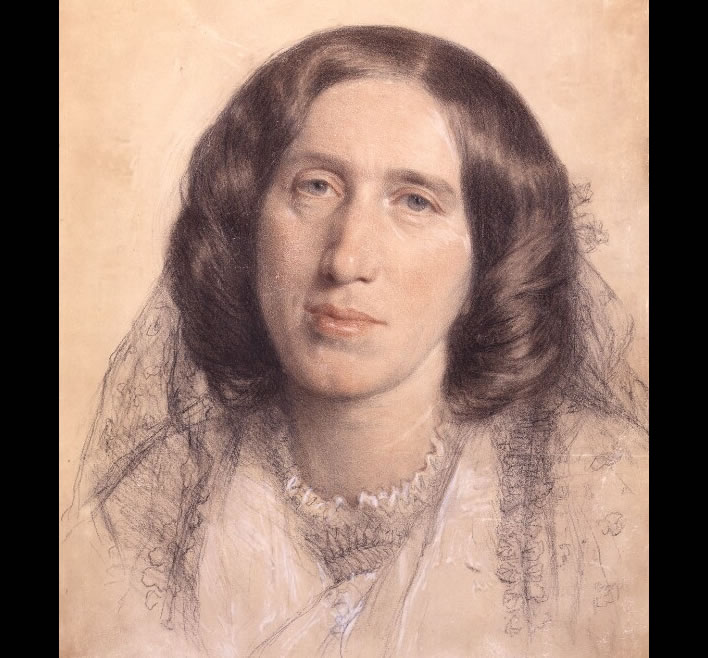

Quote of the month 1: George Eliot

The writer George Eliot (Mary Anne Evans, 1819-1880) was underway in Europe with someone else's husband, George Henry Lewes (1817–78), in 1858. She spent a comfortable six weeks in a commodious and surprisingly inexpensive suite ('a whole apartment of six rooms') in Dresden in July and August. Productive, too, for it was in that peace and quiet that she wrote a considerable part of her first novel, Adam Bede (1859).

George Eliot, portrait by Sir Frederic William Burton, 1865. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

She had already taken in with determination the art in Vienna and Prague. She visited and revisited the Picture Gallery in Dresden with remarkable dedication. She had opinions and was not hesitant at expressing them:

The most popular Murillo, and apparently one of the most popular Madonnas in the gallery, is the simple, sad mother with her child, without the least divinity in it, suggesting a dead or sick father, and imperfect nourishment in a garret. In that light it is touching.

A fellow-traveller in the railway to Leipzig told us he had seen this picture in 1848 with nine bullet holes in it! The firing from the hotel of the Stadt Rom bore directly on the Picture Gallery.

Eliot, George, ed. Margaret Harris, Judith Johnston. The Journals of George Eliot, in Cambridge Studies in Romanticism, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 326. A version is available online in George Eliot's Life, Vol. II.

She read into Murillo's Virgin and Child the opinions of the educated woman of her class. She viewed the picture as though it were one of Murillo's genre paintings, showing a peasant woman and child suffering from 'imperfect nourishment in a garret'. That perceptive observation itself is worth many paragraphs of art critic waffle. Despite the upturned eyes of the Virgin, she finds it 'without the least divinity'.

As for the bullet holes, the hotel Stadt Rom was indeed at the centre of the Dresdner Maiaufstand, the 'May Uprising in Dresden' in 1849 (not 1848, as Eliot says). The uprising was part of the revolutionary upheavals in Germany that took place between 1848 and 1849. The various attempts to overthrow some of the many rulers of the German states of the time failed or were of short duration and the status quo was soon restored. The May Uprising in Dresden was one of the last of these and was put down after the intervention of Saxon and Prussian troops.

Saxon and Prussian troops in the Dresdner Neumarkt attacking the barricades of the revolutionaries around the Hotel Stadt Rom. Image: Wikimedia [hidden by the Stadtmuseum Dresden from the view of the internet public].

Murillo's Madonna was in the firing line, but there is some doubt whether it really got all the nine bullets it so deserved. It was repaired soon afterwards – hence George Eliot noticed nothing until she was told about it by the stranger on the train.

The German Democratic Republic completely restored the painting in 1970, then took revenge on its religious iconography by using its image on a postage stamp:

The pen may indeed be mightier than the sword, but the postage stamp can do more damage than any rifle – especially when printed using a potato.

The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister on its main website currently doesn't think it's worth wasting pixels on the painting. It will, however, let you go and look at it for 12 EUR. The determined searcher will find a small image (with minimal comment) in the Online Collection, with a link to a commercial picture agency with palm outstretched, waiting to be crossed with silver – in a previous case they wanted 100 EUR from us. An adaptation of one of Captain Haddock's carefully crafted, family-friendly curses comes to mind: 'blue blistering bloodsuckers!'

Image of the month 2: The Munich Murillo

Our messing around with Murillo's Virgins didn't start with George Eliot in Dresden. It started with the German writer Christian Friedrich Hebbel (1813-1863). On 6 March of 1839 Hebbel was making a last tour of the art galleries of Munich before setting off a few days later on a hike from Munich to Hamburg, where he arrived on 31 March.

Carl Rahl, portrait of Friedrich Hebbel, 1855. Image: Photo © Andres Kilger / Alte Nationalgalerie / Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Online.

The 'hike' was no pleasant stroll: the physical sufferings of that penniless march nearly cost him his life upon arrival in Hamburg; many believe they contributed to shortening his life.

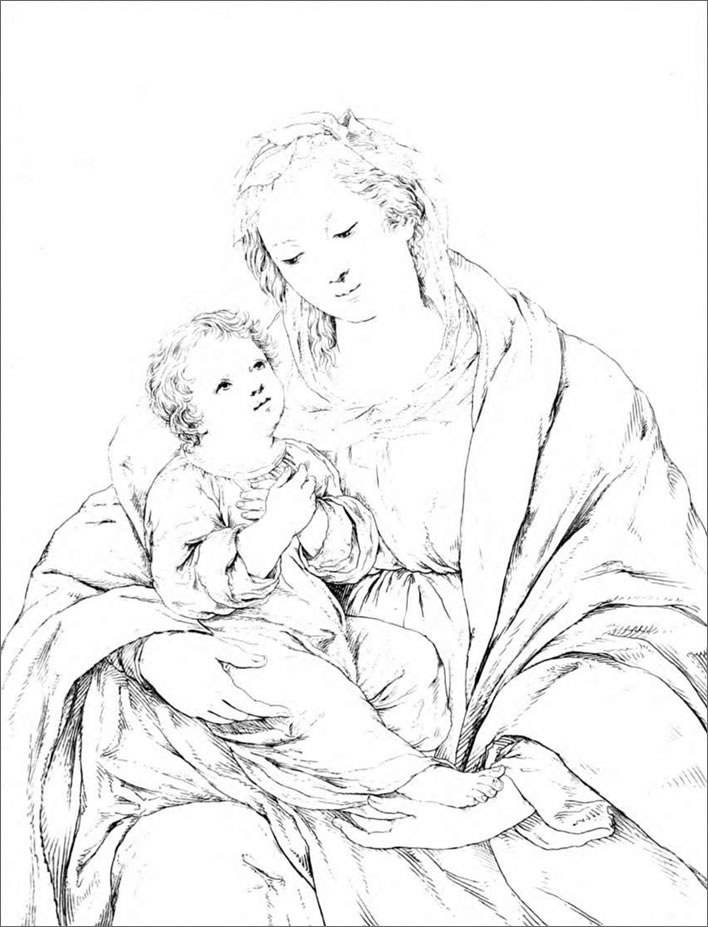

Among the paintings he encountered on his farewell visits to the galleries of Munich, one left a particular impression upon him: a Murillo Virgin and Child. This one:

Johann Nepomuk Muxel (1790-1870), etching in Muxel, Johann N. ; Leuchtenberg, Eugène de Beauharnais von ; Passavant, Johann David. Galerie Leuchtenberg : Gemälde-Sammlung seiner kaiserl. Hoheit des Herzogs von Leuchtenberg in München, Frankfurt am Main, 1851, Verlag: Baer, plate 98. Online. [Click to open a larger version in a new tab.]

Quote of the month 2: Friedrich Hebbel

Now it's time for leave-taking. Yesterday I was in the Pinacothek for the last time, today in the Leuchtenberg Gallery and in the Glyptothek.

In Hamburg it will be a great privation for me that I won't be able to see beautiful paintings and sculptures anywhere.

[…]

Murillo's Madonna. This infant Jesus blends childish naivety and the intimation of his own divinity in the most intimate way; but in this on his own. Christ seems to play with his own self.

Jetzt geht's an's Abschiednehmen. Gestern war ich zum letzten Mal in der Pinacothek, heute in der Leuchtenbergschen Gallerie und in der Glyptothek.

Es wird mir doch in Hamburg eine große Entbehrung seyn, daß ich dort nirgends schöne Gemälde und Bildwerke sehen kann.

[…]

Murillos Madonna. In diesem Christuskinde sind kindliche Naivetät und Ahnung seiner eigenen Göttlichkeit auf's Innigste mit einander verschmolzen; in diesem aber auch ganz allein. Christus scheint mit sich selbst zu spielen.

Hebbel, Friedrich. Ed. Monika Ritzer, Tobias Eiserloh, Matthias Grüne, Hermann Knebel, Uwe Korn, Maike Schmidt, Hargen Thomsen. Tagebücher, Neue historisch-kritische Ausgabe, Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston, 2017, p. 177 (6 March 1839).

The image we show here is an etching by Johann Nepomuk Muxel (1790-1870), who was from 1824 onwards the Inspektor der herzoglichen Leuchtenbergischen Gemäldegalerie. Muxel collected his outline etchings of the contents of the Leuchtenberg Gallery in an illustrated catalogue, published in various editions in 1826, 1841 and finally 1852.

The Palais Leuchtenberg in Munich was built by Eugène Rose de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg (1781-1824), the stepson of Napoleon Bonaparte, who came to fame, fortune and rank as an able general in Napoleon's service. He built the palace and started its art collection at the beginning of the 1820s. After his death his son Auguste inherited the title, then his brother Maximilian. The Leuchtenbergs' glory lasted little over thirty years. After Duke Maximilian's death in 1852, the gallery was closed, the collection divided between the children or sold. Many pieces went to Russia, only to be scattered again during the Russian Revolution.

A photograph of the Palais Leuchtenberg today. This photograph is here after some heart-searching, since almost nothing in this building is in the slightest bit authentic. The building was damaged on several occasions by Allied bombing during the war, then completely demolished around 1957. It could be argued that the new brick and steel facade sort of replicates the original, but to what purpose? The current occupants are the Bavarian tax authorities. Image: PD.

I have not yet found the whereabouts of the original painting. This situation may change when I can get my hands on the most recent Murillo catalogue.

Analysis

The components of the image are certainly unusual: the child is fully dressed in what at first seems to the modern eye to be a onesie but is really some sort of gown, the sleeves sensibly rolled up to allow for growth; the child is resting in Mary's right arm; the rendering of the child is 'miniature adult' – small head and a good thatch of curly hair; Mary is also well wrapped-up, giving us the impression that the painting was done as a study in rendering textile forms. The large wrap around her shoulders gives a feeling of great mass.

The unifying structure of the image is also unusual for Murillo: the curve formed by Mary's arms and the child's right leg binds all the elements together – Murillo's compositional sense is usually not so developed.

The interactions between the two figures are very different from the Dresden Murillo: here the Virgin is gazing lovingly at the child, whilst the child is gazing upwards to heaven. The crossed hands indicate not prayer but submission. Even in this outline sketch, the whole image is theologically and emotionally much more satisfying than the painting in Dresden. Whereas here there is a connection between Mary and Jesus, in Dresden there a separation: Mary is looking upwards and the infant is looking outwards.

Our surprise at the composition of this picture is shared by Muxel and Passavant in their catalogue of the Leuchtenberg gallery:

98 The Blessed Virgin Mary is holding in her arm the dressed infant Jesus, who, with hands laid crosswise on his breast, is looking upwards. Life size three-quarter-length portrait. This beautiful, intensely worked picture is held by some to be the work of a pupil of Murillo. In its treatment it is certainly very different from the preceding pictures of the master.

98. Die heilige Jungfrau hält in ihrem Arme das angekleidete Jesuskind, welches, mit kreuzweis über die Brust gelegten Händen, den Blick nach oben richtet. Kniestück in Lebensgröße. Dieses schöne, sehr ausgeführte Bild wird von einigen für das Werk eines Schülers des Murillo gehalten. Sicher ist es in der Behandlungsweise sehr verschieden von den vorhergehenden Bildern des Meisters. Muxel and Passavant, p. 19.

A very fair summary.

Quote of the month 3: Handbook for Travellers etc.

The anonymous author(s) of John Murray's popular Handbook For Travellers In Southern Germany thought the Murillo painting the 'gem' of the Leuchtenberg Gallery's 'choice collection':

The Leuchtenberg Gallery of Pictures, formed by Eugene Beauharnois, Viceroy of Italy, afterwards Duke of Leuchtenberg, is a small but very choice collection, well worthy of attention. It is to be feared they may be removed to Russia. The gem of it, one of the most remarkable productions of the Spanish School, is Murillo's Virgin and Child. We have here a distinguished proof that the painter's skill was as great in the more elevated province of art, as in the representation of subjects of familiar life.

A Handbook For Travellers In Southern Germany, London, John Murray, 1844, p. 52.

That painter was probably not Murillo, so the definitive and magisterial conclusion about the 'distinguished proof' of the painter's skill is misguided.

A few years before that, the indomitable Mrs Jameson, a popular all-purpose scribbler of her day, the author of the unforgettable Sketches in Canada, and Rambles Among the Red Men, stood before the 'Murillo' Virgin and Child in the Leuchtenberg Gallery and gave her readers both barrels from her hyperbole shotgun:

But the finest picture in the gallery – perhaps one of the finest in the world – is the Madonna and Child of Murillo: one of those rare productions of mind which baffle the copyist, and defy the engraver, – which it is worth making a pilgrimage but to gaze on. How true it is that "a thing of beauty is a joy for ever!"

Anna Brownell Jameson (1794-1860), Sketches of Germany: art, literature, character, Jugel, Frankfurt am Main, 1837, p. 285. Online.

It is ironic that the painting which struck so many people sufficiently forcefully that they needed to write about it, 'one of the finest in the world' as Mrs Jameson put it, has now seemingly disappeared from the world – or at least, its internet manifestation.

Anna Brownell Jameson (née Murphy), by Richard James Lane, printed by Graf and Soret, after Henry Perronet Briggs, lithograph, 1836. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London.

Image of the month 3: Hebbel's paperweights

If Murillo is one of our least favourite painters, Hebbel is one of our least favourite writers in German. As a dramatist, he has his fans, even today, but, reflecting the confused contents of his head, his diaries are a laundry list of windy, pompous and generally meaningless epigrams. There are occasional sparks, such as his perceptive comment about the Leuchtenberg Murillo, but one has to work hard to interpret them. We only understand his comment when we, too, see the picture.

Josef Kriehuber, portrait of Friedrich Hebbel, 1858. Image: Photo © Atelier Schneider / Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Online.

If you write your diary as an interior monologue, then what is the point of anyone else reading it? Contrast George Eliot's diary entry about the Dresden Virgin and Child, which throws an image on the reader's mind that is not that far from reality.

Hebbel's diaries were published last year in a two volume 'critical edition' (who said Germans had no sense of humour?) that is light on learning but heavy on paper – a wrist wrencher that weighs in at a touch under 3 kg.

Excellent for flattening out a cheese sandwich gone curly with neglect, but a test of endurance for reading.

Now we have got all that grumbling out of hearts made angry by seasonal goodwill, we are ready for anything the rest of this gruesome month can throw at us.

Merry Christmas! Hrrmph! Humbug!

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!