Two fabled stones from Graubünden

Richard Law, UTC 2019-04-24 19:06 Updated on UTC 2019-04-26

Our walk on the wild side starts just below the church of Saint Zeno in Ladir, Canton Graubünden (a.k.a. Grisons), Switzerland.

Where's that?

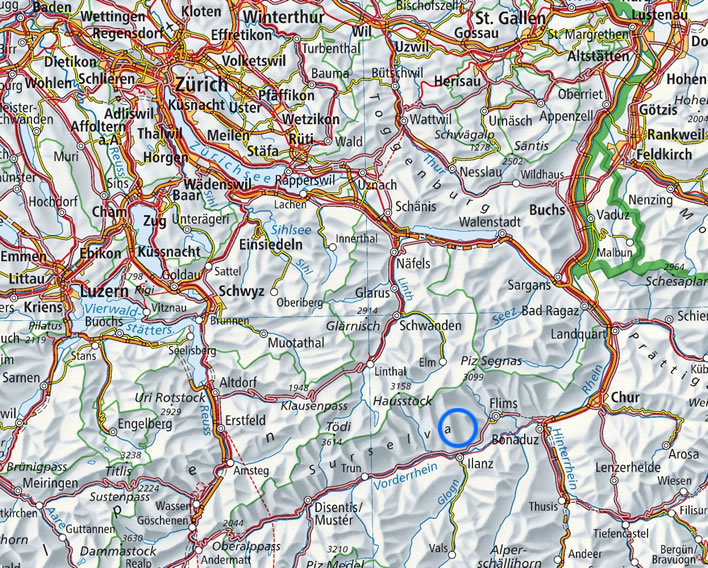

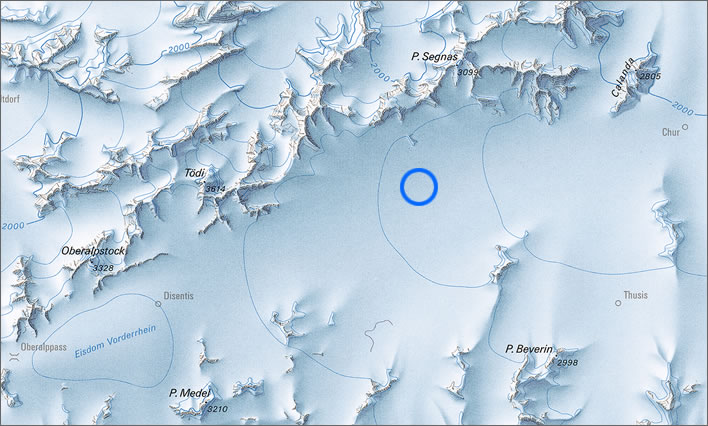

Here:

Switzerland, Surselva. The blue circle marks the location of Ladir-Schluein. The Vorderrhein, 'Anterior Rhine', meets the Hinterrhein, 'Posterior Rhine', at Reichenau and keeps going until it gets to the North Sea at Rotterdam. Image: ©Swisstopo.

The church is built on a nose of land which juts out into the valley of the Vorderrhein, the 'Anterior Rhine'. Unsurprisingly, this dramatic natural platform has been the site of several religious structures, probably going back to bronze age cults.

The piety and sacrifice of the Catholic inhabitants of Ladir has overcome the poverty of an alpine village clinging on the edge of civilisation at 1,250 metres above sea level, allowing them to build and extend their church step-by-step down the centuries.

The earliest record goes back to the late tenth century, but of this structure nothing now remains. Around the middle of the 17th century the church was a simple building with a wooden, barrel-roof. At the beginning of the 18th century the church was rebuilt and acquired the present baroque altar.

The altar of the church of Saint Zeno in Ladir. The now dingy painting in the centrepiece shows Saint Zeno skewering the Devil.

A tower was added in 1901 and the bells for it were manhandled with great effort up the track from Ilanz. The present organ was bought secondhand in 1945. A clock face was painted on the tower, but the clock (with a single face) was only installed in 1972.

The church is dedicated to Saint Zeno (?-372?), who became Bishop of Verona in 362. The few 'facts' we have about him are cluttered with the accretions of nearly two millennia of veneration and hagiographic mythmaking.

The wall statue of Saint Zeno in the church of Ladir. He is holding the church of which he is the patron in his right hand. The darker skintone and beard represents his supposed north African origins.

His feast day is 12 April, so we are a few weeks late – as usual.

His current relevance for us here, standing beneath the shadow of the alpine church of which he is a patron (one of the many), comes from the extended journeys he undertook in Switzerland, Austria and southern Germany with the aim of converting the heathen and battling heresy. Legend has it that on one of his journeys he made Ladir his base while he evangelised in the surrounding communities.

Let's follow in his footsteps on one of these local journeys. Some of the paths we will take were metalled during the wave of infrastructure improvements that were undertaken in the 1970s, but many sections are still close to the condition in which even Saint Zeno would have found them on his legendary travels.

Some of the first sections of our route differ slightly from the traditional track, parts of which have been obliterated by the roadbuilding and improvements of the 20th century. There is not much point trampling across the middle of farmed meadows just for the sake of fifty metres or so of complete authenticity.

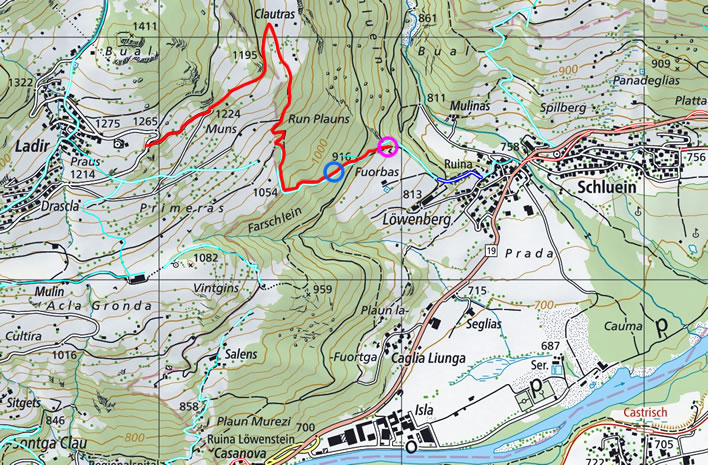

Ladir is top left and Schluein middle right. The Anterior Rhine runs along the bottom of the map and the largest town nearby, Ilanz, is just off the bottom of the map.

A hundred years ago, those journeying between Ladir and Schluein would have taken the route marked in turquoise. The first part of this is no longer feasible. Instead we follow the red route from just below Saint Zeno's church in Ladir to Saint Zeno's Stone (blue circle) and then on to the 'Baby Stone' (magenta circle). Image: ©Swisstopo.

We start out from the road just beneath the church. Our route follows the hillside along the valley of the Vorderrhein on our right. This region is known as the Surselva, from the Romansh for 'above the forest'.

Most of the route is marked as an alpine hiking route (red and white stripes).

Here we leave the metalled path from the 1970s and turn off down the ancient track that connects Ladir and Schluein, in the bottom of the valley.

The village of Schluein prefers its own wooden signposts to the modern bright yellow BAW signs on the walking routes.

By following the modern track we have overshot our entry point into the dappled wood; now is the moment to turn and track back along a path that follows the contour of the hillside.

Down into the dappled wood. The track here – the relic of centuries, perhaps millennia of human journeying – winds down the side of the valley. The descent will test just how well your knees work and whether you remembered to trim your toenails before setting off.

Although the current state of woods such as this is the product of modern forestry, we can still get a good impression of the backbreaking effort that must have gone into the clearing and preparation for cultivation and grazing of the idyllic alpine meadows we see today.

At the end of the most recent ice age, the Würm glaciation around ten thousand years ago, the sides of the valley would have been strewn with boulders of all sizes left behind by the retreating glaciers. At its greatest extent the ice cover in Switzerland was so thick that only the peaks of the highest mountains would have been visible above its surface. It was this glaciation that scrubbed the countryside into the contours we see today. As that cold period gradually came to an end the forests would have re-established themselves and the treeline would have moved upwards.

Humans returned bit by bit to the alpine valleys – leaving traces of their presence that we can still see today. Settled agriculture followed: trees were felled and the rubble left behind by the glaciers was cleared. Now we only see rolling meadows and tidy barns, apart from in woods like this.

These photographs give an idea of the steepness of the hillside we are descending.

Onwards and downwards…

A sturdy little bridge attests to the importance of this path.

— Are we there yet? My knees hurt!

— Just one more bend…

There it is, on the right: Saint Zeno's stone!

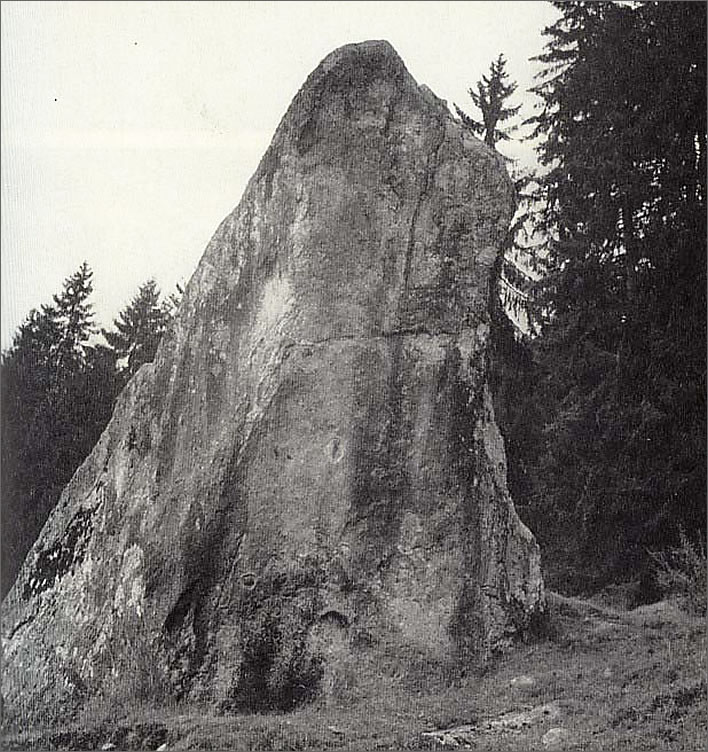

Saint Zeno's stone

The stone block we are looking at was first mentioned in an undated legend that found its way into the collection of Romansh texts known as the Rätoromanische chrestomathie. The chrestomathy was put together in heroic drudgery by Caspar Decurtins (1855-1916) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as part of the great revival of interest in the Romansh language that was taking place at the time.

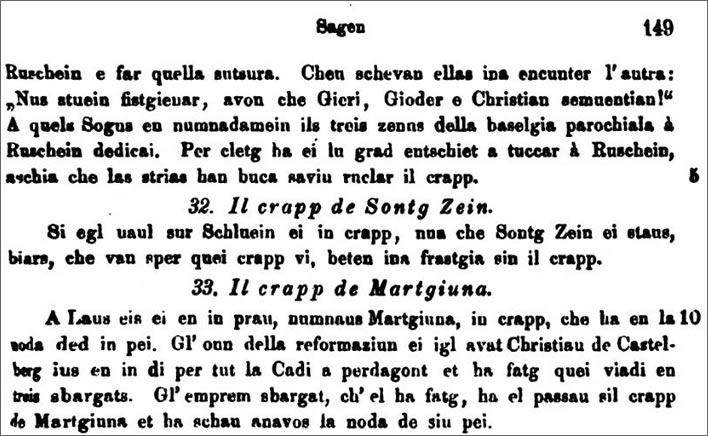

This stone was described in the legend as follows:

The Stone of Saint Zeno. In the forest above Schluein there is a stone where Saint Zeno once was, many who pass the stone lay small branches there on the stone.

[5 32] Il crapp de Sontg Zein. Si egl uaul sur Schluein ei in crapp, nua che Sontg Zein ei staus, biars, che van sper quei crapp vi, beten ina frastgia sin il crapp.

Online.

The legend behind the association of Saint Zeno and this stone was first described by the folklore collector Dietrich Jecklin (1833-1891). As is the case with all such legends, the story comes out of the fog of time at us, without author or any other identifying features. We must take it as it comes:

From the village of Schleuis [Romansh 'Schluein'] a much frequented footpath goes to the elevated village of Ladir. It passes Löwenberg Castle and winds its way through meadows and woods. — About in the middle of the route there is a stone block in the woods, 1 metre long, 2/3 across and 1/2 high, on the upper side of which two depressions are visible, as though a person had kneeled in the stone mass. — A legend about Saint Zeno is associated with this stone.

Vom Dorfe Schleuis aus führt nach dem hochgelegenen Orte Ladir ein stark betretener Fußweg, und zwar beim Schlosse Löwenberg vorbei, durch Wies und Wald sich schlängelnd. – Ungefähr Mitte Wegs liegt im Walde ein Steinblock, 1 Meter lang, 2/3 breit und 1/2 hoch, auf dessen Oberseite zwei Vertiefungen sichtbar sind, wie wenn ein Mensch in dieser Steinmasse gekniet hätte. – An diesen Stein knüpft sich eine Legende des heiligen Zeno.

It is well known that the church in Ladir is dedicated to Saint Zeno. According to the legend he was at one time travelling through wild mountain areas and the preaching to the still heathen population with such vigour that most of them converted to Christianity. The saint stayed in Ladir and in his honour the believers in Ladir (Ladurs 998) dedicated a house of God to him. The saint remained in Ladir for a long time and went from there up hill and down dale, preaching the gospel.

Bekanntlich ist die Kirche zu Ladir dem heiligen Zeno geweiht. Nach der Sage soll er einstens diese damals noch wilde Berggegend bereist und den noch heidnischen Bewohnern das Evangelium mit solchem Eifer gepredigt haben, daß diese zur großen Mehrzahl das Christenthum annahmen. Der Heilige blieb nun in Ladir, und in seiner Ehre weihten die Gläubigen in Ladir (Ladurs 998) ein Gotteshaus. Der Heilige blieb nun in Ladir lange Zeit und ging von dort aus thalein, thalaus, das Evangelium zu verkünden.

Now however the evil spirit was envious of the saint's success and attempted to stop the work of conversion, and if possible even to drag the faithful back into the Empire of Darkness. But the belief in the Redeemer was too deep for him to destroy the holy work with cunning. Satan had to take refuge in force.

Nun war aber der böse Geist neidisch auf die Erfolge des Heiligen und trachtete darnach, wie er das Bekehrungswerk desselben hemme, womöglich sogar die Gläubigen wieder in's Reich der Finsterniß ziehe. Aber zu tief war der Glaube an den Erlöser eingewurzelt,[3] als daß mit List das heilige Werk vernichtet werden konnte. Satanas mußte zur Gewalt die Zuflucht nehmen.

The construction of the church at Ladir had just begun, so the Spirit of Darkness resolved to destroy the work of the faithful. He fetched a great stone from the bed of the Rhine and carried it up into the woods so that he could destroy the church with it. — On the way he took a rest, laid the burden next to him and lay down under a fir tree.

Eben war der Bau des Gotteshauses zu Ladir begonnen, so dachte der Geist der Finsterniß, dieses Werk der Gläubigen zu vernichten, holte vom Rheinbette herauf einen großen Stein, den er den Wald hinauftrug und mit dem er die Kirche zu zertrümmern gedachte. – Unterwegs ruhte er aus, legte die Last neben sich und sich unter eine Tanne.

As he was resting, Saint Zeno came down through the woods on the way to preach the gospel in the valley. Seeing the Evil One and guessing Satan's intention from the presence of the stone block he had never seen before, he kneeled on the stone, prayed, and robbed the enraged Lucifer of any power to raise the stone again. Through his prayers he even forced the Evil One to leave the area and also leave him, the saint, and his faithful flock in peace.

Wie er nun rastete, kam der heilige Zeno den Wald herab, um in der Ebene zu predigen. Alsbald den Bösen erblickend, und an der Anwesenheit des großen, niemals an dieser Stelle gelegenen Steinblockes das Ansinnen des Satans erkennend, kniete er auf diesen Stein nieder, betete, und benahm dem darob ergrimmten Luziferus die Macht, den Stein weiters zu heben, bezwang sogar durch sein Gebet den Bösen, die Gegend zu verlassen und auch ihn, den Heiligen, und seine Gläubigen fürder in Ruhe zu lassen.

Jecklin, Dietrich. Volksthümliches aus Graubünden. II. Theil, Zürich 1874, p.3. Online Zeno.org.

The impressions Saint Zeno's legs made as he prayed can be seen to this day.

Readers who remember our piece on the Teufelsbrücke on the Gotthard Pass will recall the similar legend of satanic activity that involved the Devil wanting to throw a huge block of stone, the Teufelsstein, in an attempt to destroy the newly constructed bridge that afterwards acquired his name: the Devil's Bridge. That bit of devilry was thwarted by a quick-thinking old lady scratching a cross on the stone.

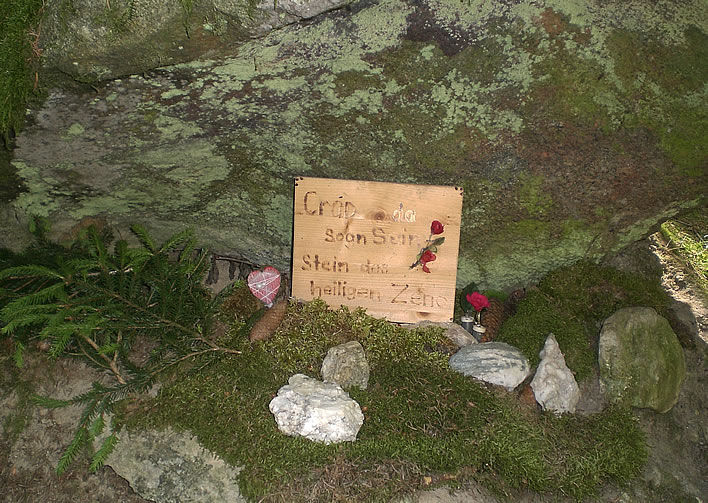

The entry in the Chrestomathy told us that passers-by were in the habit of laying some small votive offering – pine twigs or attractive stones – on Zeno's stone. The first time I visited the stone two years before the present excursion nothing of the sort was to be seen. On this occasion, all the votive stops have been pulled out:

Someone has crafted a wooden board with a poker-work inscription, picked out in gold paint, in Romansh and German, Crap da Sogn Sein / Stein des heiligen Zeno, 'Stone of Saint Zeno' and started a collection of offerings of the usual sort – hearts, flowers in holders, attractive stones as well as pine cones and branches. How many other people have been involved in adding to the collection is unknown. Readers may recall the similar devotional objects at a nearby shrine to Saint Barbara. Yes, I, atheist mocker, leave things at these shrines: you never know…

The smaller stone next to Zeno's stone is colloquially called the Devil's Stone. What role it is supposed to play in the legend is not known, since the stone which Satan intended to heave at the church in Ladir was Zeno's Stone itself.

Christian Caminada (1876-1962) was a Roman Catholic Bishop of the diocese of Chur between 1941 and 1962. He was also a Romansh scholar – he brought to a conclusion Caspar Decurtins' Rätoromanische Chrestomathie and spent much of his life investigating the folklore and local history of Graubünden.

In his book Graubünden, die verzauberten Täler, 'Graubünden, the Enchanted Valleys', he investigated the legend of Saint Zeno's Stone:

The Saint Zeno Stone is half fallen over the lower edge of the track, in such a way that one asks whether lightning or an earthquake toppled it so that it became such an obstruction for traffic that the projecting head of the stone had to be broken off. That the Zeno Stone lost the projecting point in historical times was clear when I saw with my own eyes and traced with my own hand the hole made by the iron drill for the insertion of the blasting charge.

[…]

Our own knee tested the indentations. We also saw under the stone a pile of green branches, now dried out, which those passing had left as offerings for Saint Zeno. No one admitted to seeing anyone leaving the offerings or admitted to being one of them themselves.

Der St.-Zeno Stein ist halb hingefallen über den unteren Strassenrand, dass man sich fragt, ob der Blitz oder ein Erdbebenstoss ihn so hingeworfen hat, dass er zu einem Verkehrshindernis wurde - dass man teilweise den vorragenden Kopf abbrechen musste. Dass der Zeno Stein die vorragende Spitze in historischer Ära verlor, sah ich, als mein Auge und meine Hand ein Eisenbohrloch für die Pulverladung entdeckte. […] Unsere eigenen Knie prüften die Einsenkungen. Zugleich sahen wir unter dem Stein einen Haufen grüner Zweige inmitten verdorrter Äste, welche von Vorüberwandernden dem heiligen Zeno dargeboten wurden. Niemand will die Opfernden gesehen haben oder bekannte sich als der Opfernde.

Caminada, Christian. Die verzauberten Täler: die urgeschichtlichen Kulte und Bräuche im alten Rätien, Walter-Verlag, 1961.

Bishop Caminada is correct. Here is a close-up of the hole that was drilled for the blasting charge and the fractured, uneroded surface left behind by the amputation.

If we imagine what the stone might have looked like when the nose was still attached we have to conclude that the stone would have had a very striking form. It is scarcely a surprise that a legend developed around it. Despite all my search efforts I have been unable to find any remnants that could be identified as part of the amputated nose of the stone. Had the nose been intact it would have merely been rolled out of the way, but we might equally expect that the force of the blast shattered the nose into numerous small, inconspicuous pieces.

The seemingly casual mutilation of a stone with so much religious mythology attached to it leads us to suspect that the myth of Saint Zeno's combat with the Devil may not have been as widespread as we might otherwise assume, but since we don't even know the date when the amputation took place, all must remain unknown.

Bishop Caminada's assumption that the stone was originally a standing stone which fell over at some point seems to be a step too far though. Glaciers don't have to drop stones in a vertical alignment, nor is there any indication that it was ever vertical at any time in the past. The Zeno legend itself requires that the stone lies flat so that the saint can kneel on it.

The large, concave underside with its sharp edges suggests that the stone was no solitary glacial erratic, but that it was split off from another part (in which case, where is the other part?), or perhaps even broke off from a cliff face (in which case, where is the cliff?). Until further research is undertaken, the most plausible hypothesis is that this odd stone was transported here by Satan himself on his way to wreck Zeno's church.

We now leave Zeno's Stone and continue downwards towards Schluein. We are off to see a real standing stone, the 'Baby Stone'.

Not far to go, about one hundred metres or so, heading gently downwards.

We make a right turn at a pleasant resting place, although in summer you will need to be able to come to a peaceful modus vivendi with the bees from the adjacent beehives. They have more pressing things to concern themselves with than you, though.

In the middle of all the luxuriant greenery we catch sight of it: the Crap da Pops, the Kindlistein, the 'Baby Stone'. Pop is the Romansh word for a baby, a 'suckling'; far pops is 'to make a baby'.

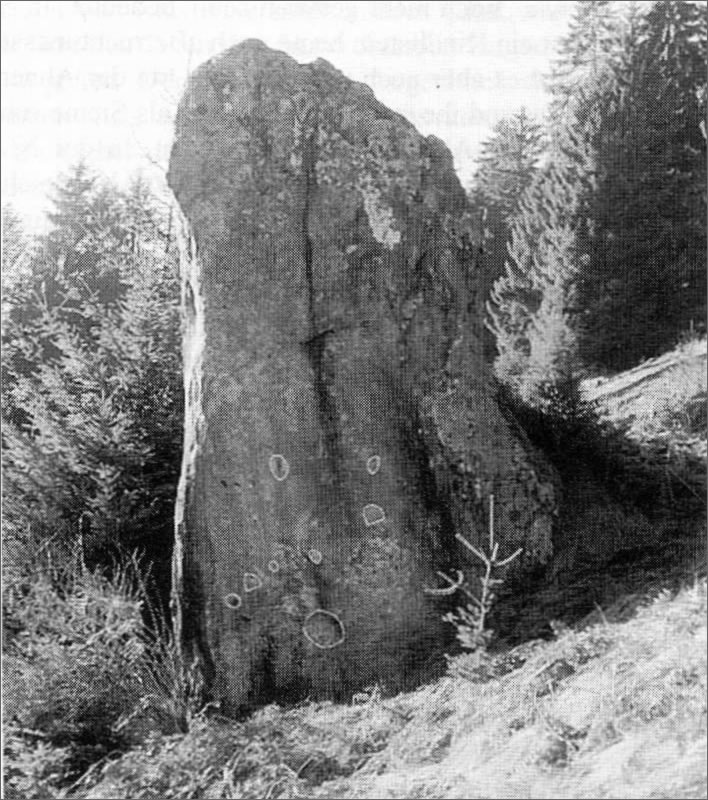

The Baby Stone

We are once more dealing with myth and legend, tales with no date and no author. In the case of the Crap da Pops, the legend is so odd that we might begin to think our ancestors were idiots – which they certainly were not. According to the legend, this stone is the place where the midwives collected the newly born babies, a story that violates every empirical fact available about childbirth.

It may have been the place where you went to leave an offering to ensure either a successful impregnation or to give thanks for a successful birth. No one knows. If today you want to make use of whatever useful services are available at the Crap da Pops you will have to be prepared to fight your way through bushes, past trees, through tall ferns and over a particularly aggressive ant colony.

The wild undergrowth hides the fact that this remarkable stone is about four metres tall. In earlier photographs we can see it in its full splendour:

The Crap da Pops. Image from Caminada, Christian Die verzauberten Täler, photographer unknown.

This is all the view of the front face we have at the time of our visit.

From an archaeological point of view, the Crap da Pops is a much more interesting artefact than Zeno's Stone.

Some researchers claim to be able to make out geometrical figures on the stone – see the chalk highlighting in the second historical photograph, shown below – but Wieland Oswald, who examined the stone in 1962, had to admit that the markings could also be the result of natural processes throughout the centuries.

Image from Derungs, Kurt. 'Mythologische Landschaft Graubünden' in Mythologische Landschaft Schweiz. Bern 1997. p. 233.

For those with a taste for the magical and mythical the valleys of the Surselva are full of prehistoric artefacts into which you can read whatever you choose with little fear of contradiction. It's a charming thought to imagine the doughty Saint Zeno asserting himself over Satan in the dappled woods through which we walked today. We wonder, though, where today's devils are lurking and who there is amongst us who can put an end to their wicked machinations.

Ninety years in the life of the Crap da Pops

The Swiss Bundesamt für Landestopografie gives the public access to its extensive archive of aerial photography.

We can use the aerial photographs taken for this region between 1939 and the present day to show how the natural afforestation of the patch of ground around the Crap da Pops has proceeded without human interference during almost a century.

Sooner or later humans come along and decide the ongoing battle between trees and rocks.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on a thumbnail to see a larger version in the main image. The tooltip contains additional information.

All images in this browser: ©swisstopo.

Looking at this area from above we are struck by the cluster of stones in the meadow close to the Crap da Pops. Whether and how this rubble field is associated with the large stone is an open question. The last image in the browser shows just about the whole extent of the cluster. The erratic pattern of tyre tracks around the stones reveal that the cluster is certainly an irritant for farming, but the effort of removing the stones, even with modern equipment, probably outweighs all benefits.

Ten thousand years in the life of the Crap da Pops

Image: Die Schweiz während des letzteiszeitlichen Maximums (LGM) 1:500000.

Had we been standing in the vicinity of the Crap da Pops (blue circle) around 20,000 years ago during the maximum extent of the Würm glaciation we would have had between 800 and 1,000 metres of ice above our heads.

The glacier was flowing from the ice dome near the modern day Disentis down the valley towards the modern day Chur, scrubbing away at the rock surface at its sides and underneath it. There was no life, neither plant nor animal, on this huge ice sheet.

Around 12,000 years ago the glaciers were in retreat, dumping everything they had picked up onto the valley floor and sides as they melted. Vegetation, animals and our ancestors pursued the disappearing tongues of ice up the valley. At some point the Crap da Pops and Saint Zeno's stone ended up in their present positions. There are numerous places where the hillside consists of boulders heaped into piles on top of each other. Satan didn't need to go all the way down to the bed of the Rhine to find his stone.

Update 26.04.2019

Added the image browser with historical aerial photographs of the Crap da Pops and the ice age section.

All the images on this page, unless explicitly otherwise credited are ©Figures of Speech. Re-use is only permitted with a link to this page.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!