Die Sterne D 939

Richard Law, UTC 2020-01-20 14:15

In our piece on the Kinsky concert given by Schubert and Schönstein around the beginning of July 1828 we discussed the dedication of an album of four poems (Opus 96) to Princess Charlotte.

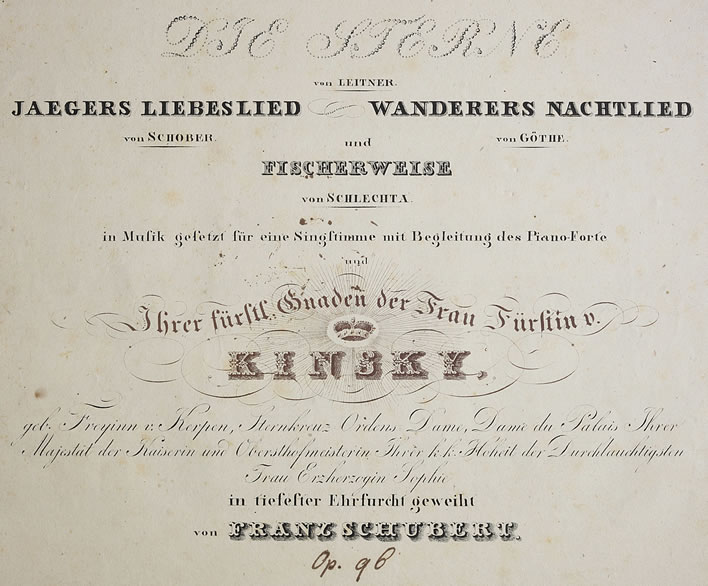

The cover page of the printed album for Opus 96 (1828), dedicated to Charlotte Princess Kinsky. No font or effect was left unused in the creation of this cover page. Reproducing the name of Leitner's poem in little stars floating at the top of the page is a nice touch. Image: Musiksammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Online.

The four poems are Die Sterne (D 939, 1828), Jägers Liebeslied (D 909, 1827), Wandrers Nachtlied (D 768, 1824) and Fischerweise (D 881, 1826), in this order.

Of these four songs, so far we have looked at Wandrers Nachtlied, which we considered to be a true diamond: a brilliant text in a brilliant setting. We have also looked at Fischerweise, a happy accident of a text which Schubert's setting managed to turn into cut glass, at least.

We can put off no longer turning our attention to one of the stones among this group, Die Sterne, written in 1819 by Carl Gottfried Ritter von Leitner (1800-1890) and composed in January 1828. Leitner himself assigns the work to 1819 in the contents list of his 1825 collection of poems.

When the decrepit state of your teeth finally compels you to visit your Bulgarian dentist, Dr Petrov, at least you can look forward to a few airmiles. For the examination of this poem there is, in contrast, no upside at all. Onwards.

Carl Gottfried von Leitner

Carl Gottfried von Leitner, like Franz von Schlechta, is yet another example of the Beamtenpoesie which plagued Austrian literature in the first half of the nineteenth century. He shared a poetic destiny with Schlechta, in that his verse also disappeared without trace. Unfortunately, also like Schlechta, he has come back from deserved oblivion to haunt us through his proxy Franz Schubert.

A lithograph of Gottfried Leitner (c.1840) from a drawing by Josef Kriehuber (1800-1876) which appeared in issue no. 5 of the Wiener Zeitschrift on Saturday 7 January 1843. Image: Wiener Zeitschrift.

Leitner was not an imperial civil servant in the conventional sense. Although he followed the necessary educational path that culminated in a Law degree at the University of Graz in 1824, instead of following the normal route of the civil servant, he took teaching posts in 1825 and 1826.

However, unlike Schubert's father, who lingered in the doldrums of teaching drudgery his whole life, Leitner's aristocratic credentials and better education took him through numerous levels of administrative and directorial posts.

It appears that Leitner never met Schubert. He was based in Graz and their paths never crossed, even when Schubert was there. Through various intermediaries, in the present case Frau Pachler in Graz in 1817, a number of his poems ended up on the Schubert song production conveyor belt.

A painting of Gottfried von Leitner (1849) by Joseph Ernst Tunner (1792-1877). Image: Neue Galerie Graz Universalmuseum Joanneum.

After the sudden death of his wife in 1846 Leitner became involved in various mystical, spiritual and theosophical cults; some may see the roots of that oddity in the simple-mindedness of the poem we are looking at here.

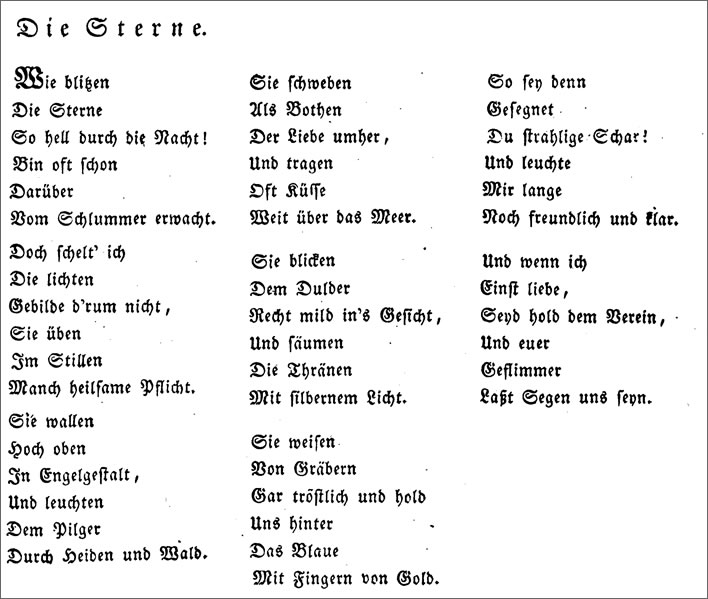

Here is Die Sterne in the form it appears in Leitner's book of poems. Schubert made two minor changes, which are highlighted in yellow. Hover the cursor over the highlight to see a tooltip with Schubert's change.

|

Die Sterne

Wie blitzen Die Sterne So hell durch die Nacht! Bin oft schon Darüber Vom Schlummer erwacht. |

The Stars

How the stars glitter so brightly through the night! I have often been awakened from slumber by them. |

| Doch schelt' ich Die lichten Gebilde d'rum nicht, Sie üben Im Stillen Manch heilsame Pflicht. |

But I do not blame the bright things for that, because they perform in silence some beneficial duties. |

| Sie wallen Hoch oben In Engelgestalt, und leuchten Dem Pilger Durch Heiden und Wald. |

They float high above in the shape of angels, and light the pilgrim's way through meadow and forest. |

| Sie schweben Als Bothen Der Liebe umher, Und tragen Oft Küsse Weit über das Meer. |

They hover around like heralds of love, and often carry kisses far over the sea. |

| Sie blicken Dem Dulder Recht mild in's Gesicht, Und säumen Die Thränen Mit silbernem Licht. |

They gaze very tenderly into the face of the sufferer, and fringe his tears with silvery light. |

|

Sie weisen Von Gräbern Gar tröstlich und hold Uns hinter Das Blaue Mit Fingern von Gold. |

They point from graves quite comfortingly and mildly, to behind the blue with fingers of gold. |

| So sey denn Gesegnet Du strahlige Schar! Und leuchte Mir lange Noch freundlich und klar. |

So bless you, you radiant throng! and shine on me friendly and clear for a long time. |

| Und wenn ich Einst liebe, Seyd hold dem Verein, Und euer Geflimmer Laßt Segen uns seyn. |

And if I should one day fall in love, look kindly on the union, and let your twinkling bless us. |

Text analysis

The content of the poem can be summarised easily: stars my wake us up at night with their light, but their benefits are great. There follows a list, stanza by stanza, of all the useful things they do: they light the pilgrim's path, they are the messengers of love, they comfort the suffering, they point to an eternal life. Leitner finally asks the stars to look kindly on any love he might find.

Leitner was only nineteen when he wrote this poem so we shouldn't be too hard on him about its obvious defects. Unfortunately, what was a youthful indiscretion when he wrote it, instead of landing in the fireplace, somehow found its way into his first volume of poetry and from thence into the hands of Franz Schubert and posterity. By 1828, Leitner should have known better and so should Schubert, but they didn't and we are stuck with it.

Even allowing for the immense differences in taste and culture between the 1820s and the 2020s, where do we begin with this drivel?

Firstly and most annoyingly, that bane of Romantic poetry, the pathetic fallacy – that is, attributing human feelings and thoughts to inanimate objects – is here in all its splendour. We heard Wilhelm Müller's miller gabbling away to flowers and streams. Here Leitner's narrator is in deep conversation with stars.

Secondly, almost every word or phrase displays some degree of poetic incompetence, but with some we can only burst out laughing.

— lichten Gebilde, 'light objects', as a synonym for stars;

— Manch heilsame Pflicht, 'some beneficial duties' (Pflicht, 'duties'?);

— Und tragen Oft Küsse Weit über das Meer, 'carry kisses far over the sea';

— blicken Dem Dulder Recht mild in's Gesicht, 'gaze very tenderly into the face of the sufferer' (recht mild, 'very tenderly'?);

— Und säumen Die Thränen Mit silbernem Licht, 'fringe the tears with silvery light';

— strahlige Schar, 'radiant throng', and so on.

If the English of stanza six, Sie weisen, is incomprehensible to you, then that is an accurate reflection of Leitner's German original.

Conclusion: This is an awful, incompetent poem written by someone with the intellectual level of a five-year-old – Beamtenpoesie, in other words.

However, we still haven't plumbed the hellish depths of this poem, its metrics.

Metrical analysis

It is often possible to scan the metre of a poem in several ways, but in the case of Die Sterne we can say that its basic metre is the amphibrach foot. We can say this with relative certainty because in his text of the poem, Leitner broke up most of the lines according to this metrical pattern.

This is a very, very odd metre to choose.

For a quick contrast consider the more normal metrical feet:

— two iambic feet [dee DUM | dee DUM],

— two trochaic feet [DUM dee | DUM dee] and

— two dactylic feet [DUM dee dee | DUM dee dee].

In contrast

— two amphibrach feet [dee DUM dee | dee DUM dee].

On hearing the term 'amphibrach' the metricist's eyebrows are raised in surprise: this is a metre that competent poets only use for special effects, the most usual of which is the galloping horse:

I sprang to | the stirrup, | and Joris, | and he|;

I galloped, | Dirck galloped, | we galloped | all three|;

Robert Browning, 'How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix' in Dramatic Romances and Lyrics, 1845. NB: the final syllable of the past participle 'galloped' is not voiced (i.e. 'gallop'd') and therefore metrically weightless.

Each line of Browning's poem consists of three amphibrach feet and a concluding iambic foot.

All readers will be familiar with the amphibrach on account of its role in the ubiquitous limerick:

There was a | young man of | Khartoum |

In this case the final foot is a spondee [DUM DUM].

Here is the first stanza of Leitner's poem with metrical markup:

Wie blitzen | Die Sterne | So hell durch | die Nacht! |

Bin oft schon | Darüber | Vom Schlummer | erwacht. |

Well I never! Three amphibrach feet and a concluding iambic foot. The reader just has to read it aloud to get a piece of Robert Browning in German.

We wonder whether Leitner's idiotic layout of the lines on the page was a way of masking the effect of the metre by suggesting implicit caesurae – but that insight would require more poetic intelligence than Leitner possesses. In sum: why would any poet in his right mind choose the galloping amphibrach for a poem about benevolent and almost unmoving stars?

Schubert, metrical master at the end of his tether

The question of why Schubert even looked twice at this rubbish, let alone set it to music is apposite, but unanswerable. In his setting, though, we can hear Schubert wandering around to try and find a melodic line that accords with the metre, without introducing galloping horses.

Gerald Moore and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau doing their best in the first two verses of Die Sterne (D 939).

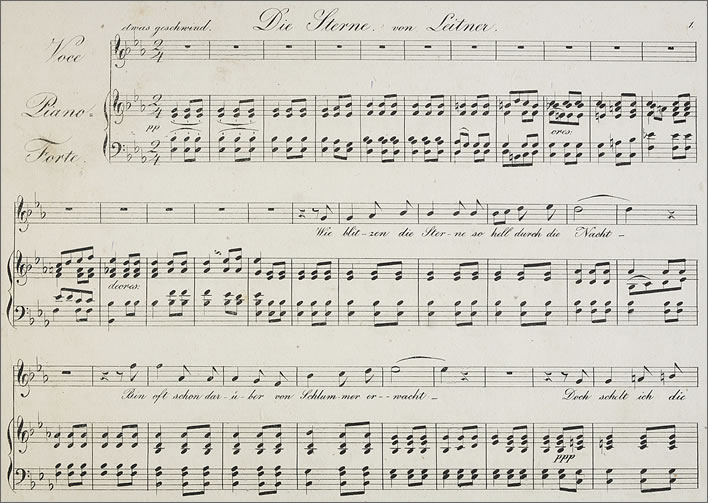

The first page of the 1828 printed score. Image: Musiksammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Online.

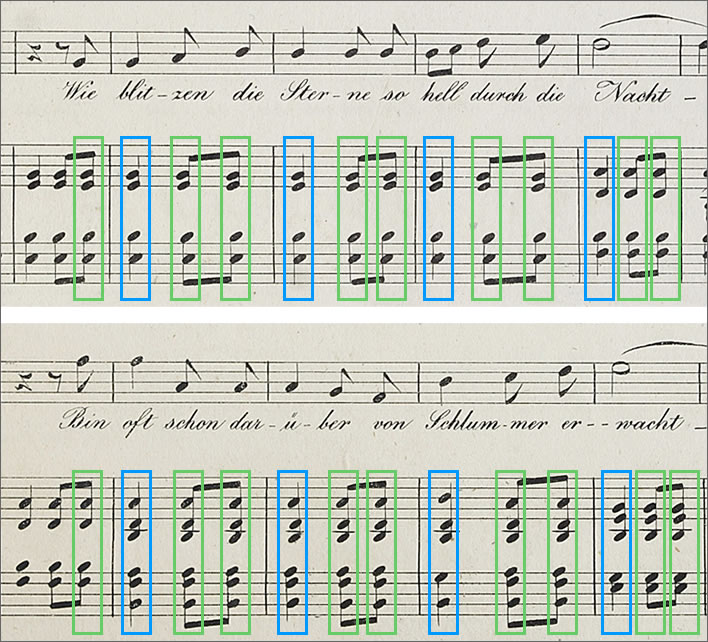

The result of Schubert's obvious desperation with Leitner's galloping horses is that the singer is yodelling amphibrachs

[dee DUM dee | dee DUM dee]

while the pianist is simultaneously plonking out dactyls

[DUM dee dee | DUM dee dee]

with a few decorative twiddles and folderols.

The accompaniment achieves this trick by scanning the line in such a way that the first syllable is an unstressed filler, allowing the remainder of the line to be scanned as dactyls with the metre asserted using pronounced chord sequences which keep the singer in line.

The dactylisation of Leitner's amphibrachs. Blue rectangles mark stressed/long syllables/notes, green rectangles unstressed/short syllables/notes. Schubert puts the first, unstressed note of Leitner's first amphibrach into the last note of the preceding bar. Image: FoS, based on an image from the Musiksammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek. Online.

As can be seen in the first page of the full score, the dactylic rhythm of the piece is asserted right from the first bar.

The world is indeed full of wonders, but your author never imagined he would find that metrical master Schubert doing this kind of thing in the service of incompetent poetry.

Leitner's odd layout of the printed poem demonstrates conclusively, however, that this dactylic construction is not the way he envisioned his poem metrically (that is, if he envisioned it at all). This poem is yet another example, therefore, of Schubert's ability to improve to some extent what idiot poets with cloth ears had written. But to this great talent there were limits, and Leitner's poem was one of them.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!