Fischerweise D 881

Richard Law, UTC 2020-01-15 10:21

Writing under the belljar

Censorship. We can say with no fear of contradiction that, for the period beginning in 1792 and lasting for at least three-quarters of a century, the literature produced in Austria is not worth reading. It wasn't worth reading then, either, but the beggars of the Austrian bourgeoisie could not be choosers.

There was also a period of censorship in the territories that we now call Germany that lasted from about 1820, but which, in that much larger and heterogeneous tapestry, was not as monolithic or uniformly oppressive as it was in the Austrian Empire.

There were the important writings of the mid-century German revolutionaries – Heine, Hoffmann von Fallersleben, Freiligrath and Co. – who wrote and managed to be published despite persecution; there were literary craftsman such as Rückert who managed to be able to do their own thing with little or no interference. We might include the work of Austrians such as Nikolaus Lenau (1802-1850) or Anastasius Grün (1806-1876), regarding them as the first green shoots of literary change in Austria.

This list of 'interesting' authors might lead the reader to assume that we are talking only of malcontents, political radicals and revolutionaries. As we saw in detail recently, the tendrils of censorship crept into every aspect of life: in effect, real people with all their flaws could not be the subject of literature in the Austrian Empire – for that kind of filth you had to go to France.

How can we be so sweepingly totalitarian in these statements?

Because expecting a writer to produce readable poetry or prose in the cultural and intellectual conditions of the time in Austria is like asking a Michelin-starred chef to knock off a dish in a field kitchen in the sodden trenches at Ypres. We can say with confidence that it is not going to succeed and that we shall have to put up with eating our baked beans cold out of the can, just like everyone else. We may put up with it, but let's not call it haute cuisine.

It's easy to spot the few writers who were producing interesting and important work during this period – they are the ones in hiding, in jail or in exile. Their sensible compatriots with day jobs were writing about nightingales, shepherdesses, fishermen and anything safely Greek or Latin.

Elevating nonentities

It is one of the recurring themes on this website that when Schubert sets the words of a poetic master, through their combined poetic sensibility a work emerges which attains even greater heights. One plus one equals three.

But so great was Schubert's genius that he was able on occasions to rescue mediocre texts and make at least something of them. Nought plus one equals two, in other words.

There is, however, only so much ballast that you can strap around the legs of the eagle before the wings can only flap ineffectually. Nought plus one equals nought. Quite a lot of Schubert's settings fall into this category, although there are few critics who will admit it.

We have looked at a number of examples of such lurking mediocrity – the Rellstab lyrics are the stand-out flop, but the quality of Wilhelm Müller's texts for both Die schöne Müllerin and (Die) Winterreise is erratic and they are frequently downright, teeth-grindingly bad. Each of these two cycles is a gilded casket before which audiences and performers reverently prostrate themselves. But when we open them up and examine their contents with a gimlet eye, there are, among the diamonds, numerous stones. The casket called Schwanengesang, as we once saw, contains only stones – and rough ones at that. Schubert audiences seem to be able to listen to this stuff with equanimity, even enjoyment. Perhaps they are just nice people (unlike your author).

The circles of poetasters

The consistently worst examples of poetic texts in the Schubert canon come from the hobby poets among Schubert's friends. We have mentioned Mayrhofer's dismal stuff elsewhere. Schober's work is uniformly gruesome. Just as bad is the work of the friends and acquaintances who dashed off pieces which they then laid on the conveyor belt of the song composing machine, probably thinking they were doing him a favour.

The favour-doing was, in fact, the other way round. It is important to understand what socio-economic process is happening here. Poetry in its written form hardly sold at all. A local paper might print a poem and pay the author a pittance. The task of this poem was to fill up the space for which there was no advertising or real news. On the day after publication the poem would pass into the oblivion that was the fate of all newsprint.

Books of poetry hardly sold at all, certainly not in any quantity. Most of them were essentially vanity publishing. But set a poem to music, that it could be sung and played, then you had a sales proposition on your hands. Schubert's song conveyor belt not only transported the poem towards the possibility of contemporary fame, it brought a good chance of immortality. Who now but the specialist would know the names Mayrhofer, Schober and those of all the many dilettantes whose names Schubert preserved for posterity?

We cannot really blame these young amateurs for the rubbish they wrote. They were all living under a censorship belljar and were not exposed to the new and the innovative. They had gone through school and higher education and thought the staid texts of Klopstock and Co. to be the height of poetics, the goal to which they should aspire. Their works never went beyond the mimetic, which is understandable, since they had spent their formative years copying moth-eaten models. The reward was for the quality of the copy, not the creation of a new model.

The gods are grudging in disbursing the intellectual gifts needed to create something really new. To a genius like Goethe they gave the striving after innovation – the ability, for example, to immerse himself in Latin poets such as Catullus, Propertius and Ovid and then to surface out of that immersion to create the previously unheard German voice of the Römische Elegien.

The civil servants in particular were so terrifed of risking their hard-won positions with the scandal that would arise were, say, a guest to spot a particularly salacious, irreligious or Jacobin book in their library (Rousseau or Holbach etc.), that they trained themselves to self-censorship – the very worst form of censorship, because after a short while you forget you are doing it and forget the wider world beyond the belljar.

Franz Schober is an interesting exception here. He was independently wealthy and could afford to do what other independently wealthy Austrians could do: buy books under the counter or have them imported.

We have to thank Schober's money and Schober's reckless insouciance that the poems of Heine's Die Heimkehr were in his library, waiting for Schubert to find them. Even so, Schubert's choice of them was done with self-censoring care, as we have also shown.

There was no point doing otherwise, for he was in an artistic dead end. His core income came from selling music to music publishers, who would never even attempt to publish something to which the censors might object or had not already passed through their hands. The composer's life came to an end shortly thereafter – the challenge of that small glimpse past the edge of the belljar – the 'Great Wall of Austria' as it has been called – remained unanswered.

We repeat: Schubert occasionally rescued a piece that really just deserved oblivion, but setting most of this stuff was a waste of his time – much of it dragged him down musically to its level of mediocrity. He would have been better just going for a walk.

Scribbling by candlelight

The dog circles three times before lying down? Perhaps, but sooner or later we settle down to snooze on the subject of this article, Fischerweise (D 881).

One of the acquaintances whose work Schubert set to music was Franz Xaver Schlechta Freiherr von Wssehrd (1796-1875) (Wssehrd is just one of the several possible transliterations from the Czech Všehrd). Schlechta was older than Schubert by only three months but he lived nearly fifty years longer. Like so many of the literary types in Schubert's circle, his day job was a career in the drudgery of the imperial civil service. He rose through the ranks in that feudal structure until he took his pension in the mid-1860s.

Heinrich Hollpein (1814-1888), portrait of Franz Xaver Schlechta Freiherr von Wssehrd, 1835. Image: hanging on someone's wall.

There are so many cases of part-time literary types earning a crust from Kaiser Franz's pyramid of social control whilst also scribbling in their leisure hours that the term Beamtenpoesie, 'civil servant poetry' has been applied to this phenomenon.

Beamtenpoesie in turn had a chilling effect on Austrian literature. No civil servant would risk the day job for the hobby. It is telling that the two Austrian exceptions we mentioned above, Nikolaus Lenau and Anastasius Grün, did not sell their souls to Kaiser Franz to become part of his machine – they now get more of our respect than the other scribblers of the time. Eduard Bauernfeld took the Emperor's sixpence for most of his adult life and contented himself with writing inoffensive comedies of manners.

Schlechta is a clear case in point. If you think we are being hard on these sensitive types consider the pointed way the Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich characterises him:

Baron Schlechta belongs in that circle of those older Viennese poets who slung the ribbons of their lyres over their military uniforms, civil servant frock-coats or priestly cassocks, in order indeed to remind themselves that they may not be more of a poet than their official dress allowed. That circle includes Castelli, Mayrhofer, Michael Enk, Anton Pannasch, Deinhardstein, Marsano und Franz von Hermannsthal.

If these gentlemen, at least the majority of them, had been able to have sung from their hearts, literature would possess works that were very different from those we now have from them.

Baron Schlechta in particular is a representative of the soft and comfortable, characteristically Austrian poetry, which at that time warbled only in the softest and melodious tones, in order at least to ring in a happier era with the inspiring and freedom loving sounds of Lenau and Anastasius Grün.

Baron Schlechta may have found the conflict between what he could sing and what he was allowed to sing to have been too deep and, after the poet had transformed himself into an imperial-royal civil servant, he sent his muse packing – and rather quickly at that.

Baron Schlechta gehört in jenen Kreis der älteren Wiener Poeten, welche über dem Soldaten-, Beamten- oder Priesterrocke das Band mit der Lyra trugen, um ja nicht zu vergessen, daß sie nicht mehr Poeten sein dürfen, als es ihnen eben ihr officielles Kleid gestattete. Dazu gehören Castelli, Mayrhofer, Michael Enk, Anton Pannasch, Deinhardstein, Marsano und Franz von Hermannsthal. Hätten diese Herren, wenigstens die Mehrzahl von ihnen, frisch von der Leber weg singen dürfen, die Literatur besäße ganz andere Arbeiten, als es die sind, denen sie einen Platz in der Literatur verdanken. Baron S. vornehmlich ist ein Repräsentant der weichgemüthlichen, echt österreichischen Lyrik, die damals nur in den sanftesten und ganz wohllautenden Tönen flötete, um später mit den berauschenden und freiheitdurchglühten Klängen Lenau’s und Anastasius Grün’s eine neue, immerhin glücklichere Aera einzuläuten. Baron S. mochte den Conflict seines Singenkönnens und Singendürfens zu tief empfunden haben und gab, nachdem der Poet im k. k. Beamten aufgegangen war, seiner Muse, und zwar ziemlich frühzeitig, den Abschied.

Given the low standard of his work we can only be grateful that he gave up early. His muse was probably quite relieved, too: 'Free at last, Nightingale, old friend, free at last!'

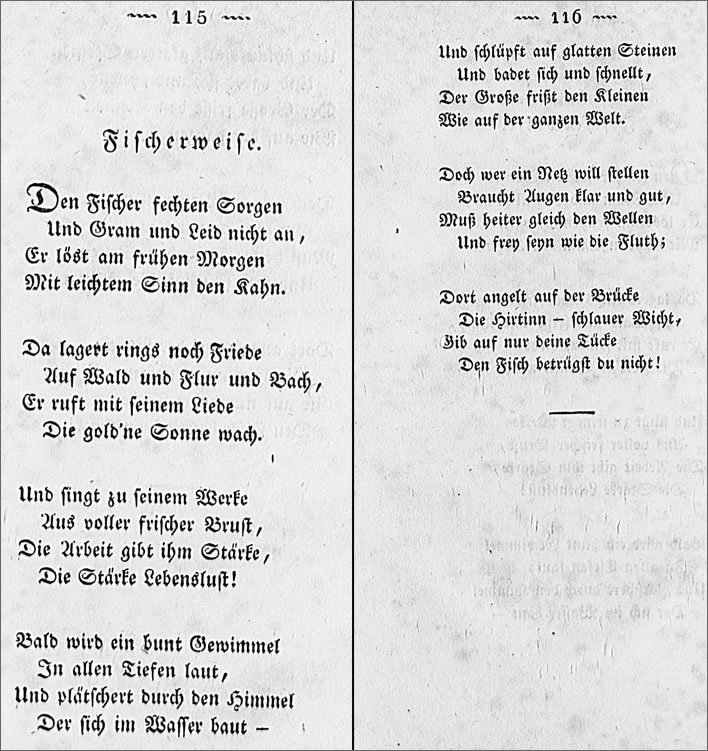

Fischerweise in the 1828 edition of Dichtungen vom Freyherrn Franz von Schlechta. Source: Klassik Stiftung Weimar / Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek.

Fischerweise: text analysis

Here is the text of his poem Fischerweise in the form in which it was set by Franz Schubert with our comments in a tasteful eggshell blue (the only tasteful thing about them):

| Fischerweise | Fisherman's song |

The title Fischerweise has its subtleties. Eine Weise has had the meaning of 'a [short] song' since Old High German. A translation into English such as 'Fisherman's Song' would therefore be superficially correct. But Weise has a much more common meaning of 'the way something is', the 'form' or 'nature' of something or even more accurately, the 'manner of doing something'. Modern German frequently refers to the Art und Weise of something, its 'nature and behaviour'. Thus, the title with all its echoes suggests that this poem is not simply a 'song' but that it is a characterisation of the 'behaviour' of a fisherman – which, when taken as a whole, is what it certainly is. Could we say 'lifestyle'?

| Den Fischer fechten Sorgen Und Gram und Leid nicht an, Er löst am frühen Morgen Mit leichtem Sinn den Kahn. |

The fisherman is not assailed by worries, sorrow or suffering. In the early mornings he unties his boat with a light heart. |

English speakers may be troubled by the sentence inversion in the first two lines. Den Fisher is in the accusative case, meaning that he is the one (not) being assailed by sorrows. Without the inversion and following the more usual subject-verb-object pattern familiar to English speakers it would be: Sorgen, Gram und Leid fechten den Fischer nicht an. The separable verb anfechten is split up into its particle an and stem fechten.

Incompetent poets frequently get themselves into metrical situations that cause them to repeat words with almost the same meaning just to make up the line. We saw this vice at its worst in Rellstab. Sorgen, Gram and Leid are almost completely interchangeable, leaving the translator to make up a list of woes to taste (which the reader shouldn't take too seriously).

| Da lagert rings noch Friede Auf Wald und Flur und Bach, Er ruft mit seinem Liede Die gold'ne Sonne wach. |

Peace still lies all around on woods, meadows and streams. He rouses the golden sun with his song. |

At this mediocre poetic level it is impossible to mention the sun without telling the reader it is golden.

| Er singt zu seinem Werke Aus voller frischer Brust, Die Arbeit gibt ihm Stärke, Die Stärke Lebenslust! |

He sings at his work from a full, fresh breast. The work gives him strength, the strength [gives him] lust for life! |

Er singt zu seinem Werke. Er, 'He', is Schubert's correction of Schlechta's idiotic Und, 'And'. Idiotic, because there is no preceding clause to which the conjunction and can be linked. This is just another of the many examples we have of the care and great discernment with which Schubert treated song texts. Only sloppy writers and five year-olds on their first literary outing would accept such a disconnected Und at the start of stanza.

| Bald wird ein bunt Gewimmel In allen Tiefen laut, Und plätschert durch den Himmel Der sich im Wasser baut – |

Soon a varied seething crowd can be seen at all depths and splashes through the sky reflected in the water. |

Ein bunt Gewimmel. It is a mistake to translate bunt conventionally as 'colourful' – it makes no sense at all. In this context we should take its other meaning of 'varied' or 'diverse' (which can also be rendered with 'colourful' in English). You might encounter eine bunte Gesellschaft, 'a mixed crowd' / 'a colourful crowd' at a party.

It is also a mistake to translate laut as 'loud'. A moment's reflection will show that this translation makes the sentence as nonsensical as bunt does: fish cannot be 'loud' and certainly not 'at all depths'. The roots of the term laut reach back to Middle High German with the original sense of 'perceptible', 'visible', 'audible' etc. In this context the best translation is something like 'can be seen at all depths' i.e. 'right down to the bottom'.

Schlechta's lazy use of that old Romantic metaphor of the sky and/or heaven reflected in the surface of the water is not appropriate here because it adds nothing to our understanding of the situation. In fact it is quite difficult to understand in the context: however we look at it, the fish are not 'rippling or splashing through heaven'. Such an image is absurd.

| Und schlüpft auf glatten Steinen Und badet sich und schnellt, Der Große frißt den Kleinen Wie auf der ganzen Welt. |

And slips over polished rocks and bathes itself and darts. The large ones eat the little ones, just as they do throughout the world. |

In his setting Schubert left out stanza five – with good reason. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau suggested that Schubert left this stanza out because it introduced a metrical change which sabotaged the flow of the song [see below]. In fact, the stanza is so bad, so out of place, that it is difficult to understand why Schlechta included it in the first place.

Once again Schlechta falls victim to 'andopathy', opening this stanza with a floating und, a conjunction that is completely disconnected from what has gone before. Worse, in the previous stanza Schlechta established the bunt Gewimmel, 'varied seething crowd' as the object of our attention. In the present stanza this 'varied seething crowd' is now doing things that such objects do not do: slipping over polished rocks, bathing itself and darting about – he is surely referring now to individual fish.

We are now suddenly faced with two lines of cracker barrel philosophy: 'The large ones eat the little ones, just as they do throughout the world'. So far we have been told nothing about one fish eating another or even the fisherman eating a fish, so this sudden philosophical interjection comes as quite a surprise for the reader, especially in the context of this idyllic Romantic scene. Schubert was quite right: away with it, the entire stanza.

| Doch wer ein Netz will stellen Braucht Augen klar und gut, Muß heiter gleich den Wellen Und frey seyn wie die Fluth; |

But whoever wants to set a net needs eyes both clear and good, must be cheerful as the waves and as free as the waters. |

Schlechta ascends once more to conjunction heaven to start the stanza with doch, 'but', 'however', 'yet' (and many other meanings). However, just as with his problem with Und, there is nothing in front of doch to which it can relate. We cannot avoid the feeling that doch is there just to make up the metre. Tsk. Tsk.

This stanza shows us the Nature Romantics at their most uplifting and their most nonsensical. Even Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), that master of nonsensical rhetoric, whose works Austrians were not allowed to read or possess, wrote better uplifting nonsense: L'homme est né libre, et par-tout il est dans les fers, 'Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains'. ['Du contract social' 1762 p. 3] Let's not think what Kaiser Franz might have said about his subjects being as 'free as the waters'.

| Dort angelt auf der Brücke Die Hirtinn – schlauer Wicht, Gib auf nur deine Tücke Den Fisch betrügst du nicht! |

There on the bridge the shepherdess is fishing – cunning creature, give up your ruse, you won't trick this fish! |

The final stanza contains some bucolic buffoonery among the rustic cast. The shepherdess, a 'cunning creature' is fishing from the bridge in a parallel situation to the fisherman from the boat. She is apparently fishing for the fisherman.

We have more poetic amateurism from Schlechta. So far the story of the poem has been presented in the third person by a narrator. Without any warning or preparation Schlechta now makes in this stanza the fisherman the narrator of the poem.

At a first reading or listening this change may just cause subliminal discomfort, but writers are really not supposed to make such changes to the point of view without at least using some device such as quotation marks. Because of this sudden change we have to cope with the change of position Dort, '[over] there', with the change of person when the fisherman addresses the shepherdess with deine/du, 'your/you' and parsing den Fisch, '[this] fish'. Up to now we have referred to the fisherman as er, 'he' – now he is tacitly ich, 'I'. A good reason why only male voices should sing this song.

The use of Tücke, 'ruse' or 'trick' in the singular is quite rare. These days it is used almost always in the plural Tücken to mean the 'tricks' or 'problems' associated with something. But this is a ruse, a cunning plan, and so must be singular.

Of course, Den Fisch refers to the speaker, the fisherman. Diesen, 'this' would be normal usage but would break the metre. Singers have to sing this in such a way as to make this clear to the audience. The simplest way is to put the stress on Den, not Fisch, where it would normally go in speech.

Performance

In his comment on the song, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau is kinder and briefer than we are: concentrate on Schubert's excellent music, never mind the text:

The song [Fischerweise] was written in March 1826 and apppeared in 1826 as Opus 96. The piano wittily characterises the naivety of the carefree fisherman with half-bar rhythms (which by the way mark the flowing tempo). The verses of the friend of Schubert's youth and benevolent critic Baron Schlechta reflect completely unspoiled cheerfulness. They animated Schubert to produce the declamatorily witty caesura in the final stanza, which follows the text without disrupting the music, in that it points ironically a long finger at the shepherdess and afterwards, almost laughingly, makes up the lost time with the rapidly spoken schlauer Wicht. A stanza of Schlechta's that did not fit into the a-b-a-b alternating rhyme scheme of the music was omitted by Schubert.

Das Lied wurde im März geschrieben und erschien auch bereits im Jahr 1826 als Opus 96. Die Naivität des sorgenfreien Fischers charakterisiert das Klavier witzig durch Halbtaktrhythmen (die übrigens das flüssige Tempo markieren). Die Verse des Jugendfreundes und wohlwollenden Kritikers Baron Schlechta spiegeln ganz ungetrübte Heiterkeit und regen Schubert zu der deklamatorisch geistreichen Zäsur in der Schlußstrophe an, die dem Text nachgeht und die Musik nicht stört, indem sie ironisch mit langem Finger auf die »Hirtin« zeigt und danach fast lachend mit dem schnell hingesprochenen »schlauer Wicht« die verlorene Zeit wieder einholt. Eine Strophe Schlechtas, die nicht in das a-b-a-b-Wechselschema der Musik passen wollte, ließ Schubert aus.

The obvious defects of the omitted stanza we discussed above.

Even crazier after all these years

A remarkable thing happened with Schlechta's published output.

At sometime before his death in March 1875 he was prompted to release a new edition of his poetic efforts. It appeared posthumously in 1876. Thus fifty years after the publication of his first bound collection of poems in 1826, we find him in his dotage effecting a complete revision of those works.

The word 'revision' is putting it rather mildly, for he did not simply dot the odd 'i' and cross the odd 't', he effectively rewrote his poems.

We don't here have space to go into the details of this process, but instead of improving his works with the benefit of hindsight and maturity, he made them almost universally worse. It appears that the old Schlechta was an even more incompetent poet than the young Schlechta.

The only good thing we can say about it is that Schlechta has chosen to have an Ich-narrator right from the beginning, which solves the problem of the narrator change at the last stanza of the original version. Everything has its price, though, and the price of that repair is the use of affected and elevated language that no fisherman would utter: blank, netzbeschwerten, Stille webt, voll Verlangen, begehrst, berückst.

Here is Fisherweise as disembowelled by the aged Schlechta. Seven stanzas became five and the metrics and rhyme scheme stayed much the same:

Bin fröhlich, ohne Sorgen,

Und blank ist meine Bahn,

Ich löse vor dem Morgen

Den netzbeschwerten Kahn.Und Stille webt und Friede

In Tiefe noch und Höh',

Es steigt bei meinem Liede

Die Sonne aus dem See.Gleich wird ein bunt Gewimmel

In allen Gründen laut,

Lebendig wird der Himmel,

Der sich im Wasser baut.Doch wer ein Netz will stellen,

Der halte kühl sein Blut,

Frisch sei er gleich den Wellen,

Doch frei auch wie die Fluth.Dort angelt voll Verlangen

Die Hirtin. Ei, du Wicht!

Den du begehrst zu fangen,

Den Fisch berückst du nicht!

Ephemeren. Dichtungen von weiland Franz Freiherrn von Schlechta-Wssehrd, Wien, A. Hartleben's Verlag, 1876, p. 113.

Let's not translate this nor explain why it is so bad –it's simply not worth it. No sane performer would try to sing this. Let's leave the task of dismantling Schlechta's reworking to German speakers, although they, too, will have better things to do with their time.

Gilding the dandelion

Not every poem needs to arise de profundis – the smiling muse on the flowery sward has her legitimate place. Schlechta's Fischerweise is not terrible, at least if we don't look too closely.

Schubert improved it, bringing it from being a poem with unmissable, discordant defects (particularly stanza 5) to being something readable, singable and entertaining. With one more heave he added a layer of delightful music and created one of his most enjoyable songs. That's Schubert for you all over – despite all the textual deficiencies of Schlechta's poem he turns it into a musical triumph.

In some ways the poem and its song is the very model of the 'flowery' Romantic (as opposed say to the 'courtly' Romantic or the 'spooky' Romantic). We have Nature and within it simple, rustic occupations without civilisational complexities, the man – it's always a man: girls were maids, shepherdesses or king's daughters – the man relies on his own strength and his own wits.

It's all quite sad, really. We might care to imagine Schlechta trudging through his school years in the Kremsmünster Stift, declining Greek, Latin and German (his native tongue Czech), acquiring the patina of French and Italian, trudging through his philosophy classes in the Gymnasium and then his Law degree at the University of Vienna, trudging through his dogsbody days in the imperial administration and finally peaking at honorable respectibility as a civil servant with a high rank appropriate to his baronial status.

Then we read the first three stanzas of Fischerweise about the carefree man who goes about his trade in the peace of the natural world, someone who can sing at his work and who is not chained to a writing desk. We quite like and admire the drudge who can write poetry like that.

But when we read the fifty short and four long – all too long – poems of his 1828 volume Dichtungen vom Freyherrn Franz von Schlechta – the first volume which never had a second volume, for Schlechta put down his laurels and his poet's pen and dedicated himself to fulltime paid drudgery – when we read that through we have to say that he may have tinkered with the nuts and bolts of verse writing, but that he was never a poet.

After a while we soon realise that we are simply in the presence of a mediocre mind, a mind without a single interesting or new thought in it. We realise this because, in poem after poem, we have learned nothing, we have encountered no insight that we haven't encountered twenty times previously. Finally, on page 115 we come across Fischerweise, but by now are probably too numbed to see its potential. Schubert clearly had more staying power. Only another 135 pages to go!

The bucolic poetry of the 'Nature Romantics' could be written well. We looked at one example of a delightful trifle written by Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis (1762-1834), Der Jüngling an der Quelle, a jewel of a poem set to music by Schubert as D 300. But poet Salis-Seewis was an interesting person with a brain full important deeds and careful words. We feel that we would come away from a lunch with him greatly stimulated and enriched in mind and spirit. In contrast, Schlechta has nothing in his head that is worth the knowing.

It was Schubert who not only made Fischerweise worthy of our attention, he elevated it to an entertaining vision from the Romantic mind. Yet one more poet rescued from complete oblivion. Whether that is a good thing or not, only the reader can decide.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!