The trembling aspen

Richard Law, UTC 2019-09-27 14:12 Updated on UTC 2025-07-28

Update 28.09.2019 – Aerial photos

Update 30.09.2019 – Audio examples

Update 28.07.2025 – Grey wolves, the aspens' best friends

Clichés stick onto language like chewing gum onto pavements or shoes. Even today, journalists write on their 21st-century devices, without a blush, that a new CEO is about to 'take over the reins' at a company. We can safely assume that the number of their readers who are familiar with this manoeuvre in a horse-drawn carriage or whilst riding shotgun on some Wells Fargo stagecoach is probably zero.

For those who missed out on the romance of the Wild West in their childhoods there is always the trusty nautical alternative 'taking the helm', which pleases Hornblower readers everywhere.

Such pedantry may keep us grumblers warm at nights, but it doesn't really matter, for we all 'know what they mean' with these now hackneyed(!) phrases.

As shown in those two examples, these pieces of linguistic chewing gum often got stuck on the language long ago, in very different times, well before the various technological and social revolutions that have swept over us. Our modern, quickfire verbal lifestyle, particularly in social media, brings new sticky clichés a-plenty, but the old stuff still soldiers on(!).

Trembling leaves

Some phrases are not only irritating because of their lack of connection with modern life but also because they are often not very good similes in themselves. When did you last see a leaf 'tremble', for example? Trembling 'like a leaf' is a very poor example of trembling. A similar phrase has established itself in French, too: trembler comme une feuille.

The solitary European aspen (Populus tremula) which will be the source of most of the aspen images in this article, here taken in early summer. The tree is around 80 years old and consists of two trunks with some other species embedded in the cluster – a characteristic grouping for the uncultivated aspen. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

German has a similar phrase, but one that is much more precise: zittern wie Espenlaub, 'tremble as the leaves of the aspen'. Not only do we have a particular species of plant, a tree, the aspen (a.k.a. the 'trembling poplar'), but we have an implicit mass noun, das Laub, 'leaves' or 'foliage' as opposed to a single leaf, das Blatt, 'leaf'.

The small leaves of the aspen, captured here in mid-tremble. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

The leaves of the aspen (at least the trembling poplar variety) do indeed tremble. In the following short video of aspen leaves in action, in those scenes which include the leaves of other species you will see just how 'trembly' the aspen leaves are compared with other leaves.

At the time when the morning stars sang together, the Architect of the Universe developed an interesting construction for the leaves of the aspen (and some other poplar types, as well as one or two other trees, such as the birch and the maple).

The leaves are relatively small and hang down on long, thin stems, which droop under the weight of the leaf. The stems have an elliptical cross-section, in a ratio of 2:1. The leaves are much stiffer than the stems, meaning that they keep their shape during movement. Even light air currents cause the leaves to swing from side to side as well as rotate about the axis of the flattish stem.

The leaves of the aspen held on delicate stems. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

This structure of flexible stem and stiff leaf forms a resonator, the movements of which are damped by the surrounding air. Because of the weak coupling provided by the thin, flexible stems, the leaves can twist and turn in the lightest breeze and move largely independently of each other. Thus, in a wind, not only the individual leaves move but the entire tree shimmers.

Branches of aspen leaves. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

When the first prototype emerged from the Divine Workshop, the Architect of the Universe looked, and saw that it was good.

The circles of heaven are not populated by vague metaphysical beings but by hard-headed empiricists who know how to create worlds and make their contents work. Angelic tests showed that these fluttering leaves not only substantially increased each leaf's ability to transpire water vapour, but also increased the absorption of carbon dioxide (that delicious plant food) substantially. Even better, the movement of the leaves even in the smallest air currents cooled them, thus increasing the efficiency of the photosynthetic reactions taking place within them.

Aspen branches in a stiff wind. The thin, very flexible stems allow the leaves to adopt aerodynamically efficient positions that protect them from damage in strong winds. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Unlike the trees with old-fashioned, rigid leaves, the aspen and the feathery birch (and to some extent the maple, even with its statelier oscillation) can produce the same amount of energy but from a much smaller leaf mass.

This is important because the cycle of vernal leaf creation and then autumnal leaf destruction represents a tremendous factor in the energy balance of the tree: if the leaf mass requirement can be reduced, then more energy from food consumption is available for growth, which, in turn, is one of the reasons why the aspen and its fellows belong to the most rapidly growing tree species. Even the near circular shape of the aspen leaf offers an optimum balance of surface area and material.

The many small leaves are borne in layered arrays for the efficient collection of sunlight. The bark of the trunk and branches has photosynthetic abilities which can process sunlight even during winter. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

The angels, archangels and seraphim in the testing team lowered their clipboards, looked up and said: 'God, you're good!'

One of our two aspen trunks is a lady. In early spring we find her shamelessly dangling her assets, waiting for any passing pollen from a male tree. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

She does not have to wait long, because the tree growing right next to her is a gentleman aspen, as we can tell from the presence of the male catkins. They will do their stuff and be quickly discarded, allowing the tree to put its efforts into unfolding and growing its leaves.

Afterthought: A quick survey of some of the other aspens in the area shows that every aspen surveyed is formed as a pair of two adjcacent trunks or trees, leaning out to form a V-structure which reduces competition for light. The pairs are presumably male-female married couples. The Architect of the Universe was really firing on all cylinders when this tree was on the drawing board.

Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

The pollen from the gentleman aspen has done the deed. The lady is heavy with seed that is covered in long fine hairs to catch the wind. Everything about the aspen – its delicate leaves, its windborne pollen and its seeds, now pluming for flight – speaks of a tree of the wind. The delicate leaves are just beginning to emerge. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

At some point, the female catkins with their aerial seed are cast off; the aspen has to get on with unwrapping its leaves, ready for summer. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

When the leaves finally appear their pale yellow-green is suffused with a delicate coppery tinge. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Nowadays, the aspen's growth efficiency is its doom: our modern ecological devils look at it and think what a wonderful way to produce wood quickly for biomass burning. The empiricists in Heaven look down on this plan to destroy by fire one of their most elegant and intrinsically beautiful creations on an industrial scale in order to reduce the amount of plant food in the atmosphere. They look at each other and wrinkle their angelic countenances and ask: 'who made these humans?'

[4] Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth? declare, if thou hast understanding. [5] Who hath laid the measures thereof, if thou knowest? or who hath stretched the line upon it? [6] Whereupon are the foundations thereof fastened? or who laid the corner stone thereof; [7] When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

The Bible, King James Version, Book of Job, 38:4-7.

'That wacko chained up in the cellar'.

Four photographs of the aspen in autumn. The aspen's leaves turn pale yellow, then gold, leaving the showy stuff to other species. Images: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on an image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The evidence of aerial photography shows that our aspen began life between 80 and 90 years ago. Images: swisstopo.

This aspen has survived the chainsaw for eighty-odd years only because it has made common cause with a large rocky outcrop: nothing would be gained by cutting it down. What is tree and what is rock? Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

German trembling

The phrase zittern wie Espenlaub has existed in written German in some variant or other since the beginning of the 17th century and probably earlier (Martin Luther used a similar expression). The motion of the aspen leaf is such a good physical representation of 'tremble' that it is no surprise that it has been in use in German as a simile for all forms of trembling right up to the present day. The simile is almost always applied to the verb zittern, 'to tremble', but occasionally similar words such as beben, 'to move', 'to quake' are introduced.

The question of just how many modern, metropolitan German speakers understand the physical image of what is meant when an aspen 'trembles' is open and cannot be resolved here.

The aspen in late summer, just hinting at the proximity of autumn. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

The Grimms' aspen

The longevity of the simile may be due to the fact that the Brothers Grimm used it on several occasions in their children's stories (1812-1815). As these went through edition after edition, the striking image of the trembling aspen leaves will have certainly stuck in the receptive brains of its little readers and listeners.

In Die drei Schwestern, 'The Three Sisters', German tots encounter the princess who zitterte wie Espenlaub. In the tale Die sechs Diener, 'The Six Servants', children learn of the servant named only der Frostige, the Icy One, who, after surviving a three-day fire, zitterte wie ein Espenlaub among the ashes. In Die Gänsehirtin am Brunnen, 'The Goose Girl at the Fountain', they hear of the girl who Zitternd wie ein Espenlaub lief sie zu dem Haus zurück, 'ran home trembling like aspen leaves'.

Heine's aspen

Despite the centuries of usage of the venerable phrase, the image of the trembling aspen was so good that even punctilious writers of German could not resist it. Even Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), that opponent of all that was faded and fossilised in German, used it in Die Harzreise of 1824:

Ein kaltes Fieber rieselte mir durch Mark und Bein, ich zitterte wie Espenlaub, und kaum wagte ich das Gespenst anzusehen.

A cold fever trickled through my bones, I trembled like aspen leaves and scarcely dared to look at the ghost.

Heinrich Heine: Werke und Briefe in zehn Bänden. Band 3, Berlin und Weimar 1972. Die Harzreise.

As we have noted elsewhere, caution is always advised when reading Heine. At this point in Die Harzreise he is indulging in some fine satirical mockery of 'Doktor Saul Ascher' and the ghosts and ghouls which played such a major role in the German literature of that time. It seems probable that Heine reached for the phrase zitterte wie Espenlaub just because it was a threadbare way that the ghost and ghoul brigade in the Romantic literature of the time described someone's reaction to the many frights they had to endure.

Chamisso's aspen

In 1833 Adelbert von Chamisso (1781-1838) wrote a folksy ballad Der rechte Barbier, 'The right Barber' based on a tale by that folksy teller of folksy tales Johann Peter Hebel (1760-1826). A barber, confronted with a customer who threatens to stab him to death should the barber cut him whilst shaving him, zittert wie das Espenlaub.

With such a threat hanging over him the barber fled, leaving the task to his assistant. He in turn thought the job not worth the risk and delegated it to the young apprentice. He shaved the man without incident and not only pocketed the price for the shave but also earned a substantial tip. When the customer asked the apprentice why he was so brave when his superiors had been so cowardly, he pointed out to the customer that he would have slit the customer's throat long before his hand reached his dagger.

Keller's aspen

Of all the examples from German writings with which we could have persecuted the reader we shall content ourselves with one last one, a particularly fine simile from the Swiss writer Gottfried Keller (1819-1890), in his 1882 'novel cycle' Das Sinngedicht:

Erschien der Raum der sonst ziemlich großen Zimmer hiedurch beengt, so wurde der Umstand noch bedenklicher durch einige Eckgestelle, auf deren schwank aufgethürmten Stockwerken eine Menge bemalten oder vergoldeten Porzellanes und unendlich dünner Glassachen stand und zitterte wie Espenlaub, wenn ein fester Tritt über die Teppiche ging.

Even though the otherwise rather large room was thus already narrowed, it was even more puzzling that there were also several corner pieces with stacks of frail shelves on which stood a large amount of painted or gilded porcelain and endlessly thin glass objects, which trembled like aspen leaves when someone with a firm step walked across the carpets.

Keller, Gottfried: Das Sinngedicht. Berlin, 1882, Neuntes Capitel, Die arme Baronin, 155-216, page 166. Deutsches Textarchiv.

The aspen and Jesus

Alongside the trembling of aspen leaves used as a symbol of fear or inconstancy, a religious tradition grew up which provided 'explanations' of the reason why the aspen trembles.

This statement is really the wrong way round, because in reality the physical fact of the trembling aspen was adduced as an explanation and confirmation of a religious legend.

Out of this rich casserole of legends, tall tales and assorted humbug we shall just ladle out a couple of dumplings, which can stand as representatives of what was going through the heads of the German people around the beginning of the nineteenth century in respect of the trembling aspen.

Tieck's aspen

The first of these legends comes from Johann Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853), who was one of the founders of the Romantic movement in Germany (rustics, spooks and medieval knights). His volume Romantische Dichtungen, 'Romantic Writings', was published in 1800 in Jena.

In it we find his reworking of the much older tale of Rotkäppchen, 'Little Red Riding Hood'. The modern tale has been sanitised almost beyond recognition in order to preserve the sleep of today's tots: in Tieck's version Rotkäppchen ends up dead – though in earlier times her fate was generally worse than death (and you know what that means), followed anyway by death, dismemberment and now and again some cannibalism.

In later editions of his tale Tieck embedded his Rotkäppchen story in a commentary which announced that the tale was an attempt to make a tragic drama out of an 'extremely stupid' fairy tale. It is clear that his subject and the low grade versification in which he treated it was an attempt to parody the rustic characteristics of the language of the common people. Beyond that… who knows? Doctorates have been and will be handed out in gratitude for such explorations, but we must keep our focus on our trembling aspen.

Here is the legend of the trembling aspen from Ludwig Tieck's Leben und Tod des kleinen Rotkäppchen, 'Life and Death of Little Red Riding Hood'. Please note that the English of the translation has been left as bad as the German of the original – a pseudo-language full of infelicities that was used to (mis)represent the speech of the common people by highly educated literary Romantics attempting to affect the common touch:

|

Rothkäppchen.

Was ist das für ein Baum da, dessen Blätter So hastig flispern, als wenn sie zittern? |

What kind of a tree is that, whose leaves flutter as though they were trembling? |

|

Großmutter.

Der wird der Espenbaum genannt. |

That's called the aspen tree. |

|

Rothkäppchen.

Aha! Mir ist ein Sprichwort bekannt: Er zittert wie 'ne Espe; das kommt daher! Wovon zittert aber wohl der Baum so sehr? |

Ah! I know a saying: he trembles like an aspen; that's where it comes from! Why does the tree tremble so much? |

|

Großmutter.

Das will ich dir gern sagen, mein Kind, Nur schlag es nicht gleich wieder in den Wind: Als unser Herr Christus in Menschengestalt Hatt' auf der Erde seinen Aufenthalt, Da wandelt' er oft durch Berg und Wald. … |

That I shall tell you, my child, but just don't forget it again: When the Lord Jesus in human form was here on earth he wandered often through mountain and wood. … |

|

Großmutter.

Herr Christus reiste von Ort zu Ort, Seine Lehr zu predigen, Kranke zu heilen, Und uns sein Evangelium zu ertheilen. |

The Lord Jesus journeyed from place to place to preach his teachings, heal the sick and preach his gospel to us. |

| So ging er auch einst durch einen Wald, Die Bäum' erkannten ihn alsbald, In ihrer Unvernunft fingen sie an sich zu neigen Und bis auf die Erde herunter zu beugen, Rauschten dazu, als wenn sie grüßten Und seine heiligen Fußstapfen küßten, Die Eiche, die Buche, und wie man sie nennt, Machen vor Gottes Sohn ihr schön Kompliment. |

He went once through a wood, the trees recognised him straight away, in their innocence they began to lean and bend down to the ground, rustling, as though they were greeting him and kissing his holy footsteps, the oak, the beech and whatever they were called paid their respects to God's son. |

| Wie sich nun jeder Baum in Demuth wendt, Sieht der Herr Jesus, daß das Espenholz Grad aufrecht steht in seinem dummen Stolz, Ihm auch durchaus will keine Ehr erzeigen, Den steifen Rücken nicht zur Demuth neigen. |

As each tree in humility turned, the Lord Jesus saw that the aspen stood erect in its stupid pride and did not want to show him any respect, the stiff trunk not bending in humility. |

| Da sprach der Herr: du willst mich nicht begrüßen, Du stellst dich an, als wär ich nicht zugegen, Dafür sollst du beständig rauschen müssen Und dich in allen deinen Zweigen regen, Und selbst im allerstillsten Wetter Mit deinen grünen Läubern zittern! Die Angst befiel den Baum, als er so sprach, Er zittert fort bis an den jüngsten Tag. |

So spake the Lord Jesus: you do not want to greet me, you behave as though I am not here, for that you must always whisper and move in all your twigs and even during the calmest weather tremble with your green leaves! Fear overcame the tree as he thus spoke, he trembles on until the Day of Judgement. |

Ludwig Tieck, 'Leben und Tod des kleinen Rothkäppchens. Eine Tragödie' in Romantische Dichtungen, Frommann, Jena, 1800, pp. 460-501. Excerpt p. 475.

Rückert's aspen

The second of the legends comes from Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866), not a Romantic in the proper sense of the term, in his poem Die Espe in Erinnerungen aus den Kinderjahren eines Dorfamtmannsohns. Although the work was published in 1829, its subject relates to the 1790s, the years when Rückert was growing up in the village idyll of Oberlauringen.

In Rückert's telling, the legend is that, during the crucifixion of Christ, whilst all other trees trembled at this act, the aspen alone had remained unmoved and was now cursed to be in almost constant motion:

| Als den Herrn ans Kreuz geschlagen Nun des Feldes Bäume sahn, Kam ein Zittern und ein Zagen Allen fernen, allen nah'n. Nur der Espe Krone Ließ die Blätter ohne Beben in die Lüfte ragen, Gleich als ging sie das nicht an. |

When the trees of the field saw the Lord nailed to the cross a trembling and a fear struck all those far and near. Only the crown of the aspen held up its leaves in the air without moving, just as though they couldn't care. |

| Damals ward der Fluch gesprochen, Und ihn hörte Berg und Kluft: »Daß dir sei dein Stolz gebrochen, Zittre künftig jeder Luft! Andre Bäume zittern Nur in Ungewittern, Zitternd soll das Herz dir pochen, Wenn im Wald ein Vogel ruft. |

Then the curse was uttered and was heard by mountain and gorge: 'Henceforth that your pride will be broken you will tremble in every air! Other trees tremble only in storms, but your heart will tremble whenever in the wood a bird calls. |

| Zittre, wo im Erdenkreise Künftig du entkeimst dem Staub! Jedes Blatt soll zittern leise, Bis es wird des Herbstwinds Raub. Und in allen Tagen Soll man hören sagen Dir zur Strafe sprichwortweise: Zittern wie ein Espenlaub!« |

Tremble whenever in the seasons you release your seed! Every leaf shall tremble softly until it is taken by the autumn wind. And down all the days one shall hear it said of you proverbially: tremble like aspen leaves!' |

Friedrich Rückert: Werke, Band 1, Leipzig und Wien [1897], Die Espe, p. 231-232.

'Down all the days one shall hear it said of you proverbially' – well, that part was certainly true. We note in passing that, unlike Tieck, Rückert does not affect or mock the language and beliefs of the common people – he was a tremendous German patriot – he makes a respectable and workmanlike poem out of the legend. German speakers reading it will enjoy its moments of typical Rückert cleverness (wo im Erdenkreise / Künftig du entkeimst dem Staub).

Another legend had it that the cross on which Jesus was crucified was made of aspen wood and that the trembling memorialised this. We could go on and on about the legendary background of the trembling aspen, but our readers' eyelids are already drooping with boredom.

Suffice it to say that the cliché of the trembling aspen – with or without the religious decoration – became a fixture in German culture and is still there today.

English trembling

The aspen tree in early summer. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Chaucer's aspen

There is a long tradition of the trembling aspen in English writing, too. Its most notable beginning is in Geoffrey Chaucer's (c.1343-1400) 'Summoner's Prologue' (late 14th century), part of the Canterbury Tales, in which the Summoner (a server of ecclesiastical writs) became enraged at something the friar had said of him:

This somonour in his styropes hye stood;

Upon this frere his herte was so wood

That lyk an aspen leef he quook for ire.This Summoner in his stirrups stood high;

At this friar his heart was so enraged

That like an aspen leaf he quaked with ire.

Geoffrey Chaucer, 'The Canterbury Tales', ed. F.N. Robinson, 'The Summoner's Prologue', ll. 1665-1667, online.

The shaking was caused in this instance by rage, not fear. Chaucer used the image of the trembling aspen once more in Troilus and Criseyde, for the moment when Troilus and Cressida went on their first date:

Criseyde, which that felte hire thus i-take —

As writen clerkes in hire bokes olde —

Right as an aspes leef she gan to quake,

Whan she hym felte hire in his armes folde.Cressida, when she felt herself thus taken —

As chroniclers write in their old books —

Just like an aspen leaf began to quake,

When she felt him enfold her in his arms.

Geoffrey Chaucer, 'Troilus and Criseyde' ed. B.A. Windeatt, ll. 1198-1201, online.

Neither rage nor fear, but some other high emotion. Our female readers will probably know what this is all about.

Chapman's aspen

In its entry on 'aspen' the Oxford English Dictionary points us helpfully to George Chapman (c1559-1634). When we examine his works in detail, he turns out to be a bit of a fan of the trembling aspen simile, using it very creatively on four occasions.

In his shorter poems he wrote of exiling 'aspen fear' out of the forces of love [The Song Of Corinna]; of a stillness so complete that 'not an aspen-leaf is stirr'd with air' [The Song Of Corinna]; on another occasion of a 'dead calm', in which not 'one leaf / Of all her aspen pleasures, ever stirs' [A Fragment Of The Tears Of Peace].

Chapman's invention, 'aspen fear', showed his creative use of the simile; even greater creativity is shown in the fourth occurrence of the simile, in his play Caesar and Pompey, where we encounter the 'aspen soul' of the fearful person:

he that feares the Gods … all things feares;

Earth, Seas, and Aire; Heauen, darknesse, broade day-light,

Rumor, and Silence, and his very shade:

And what an Aspen soule hath such a creature?

George Chapman (1559?-1634), Caesar and Pompey a Roman tragedy, declaring their vvarres. Out of whose euents is euicted this proposition. Only a iust man is a freeman.

Keats' aspen

Hearing the name Chapman, literary types think of John Keats' (1795-1821) silly poem On First Looking into Chapman's Homer – you know the one, 'Much have I travell'd in the realms of gold', written in 1816 when the farthest realm of gold the Cockney poet had reached had been Margate.

In a connection that has no significance whatsoever apart from giving us a chance to abuse that easy target Keats, it turns out that the trembling aspen pops up twice in Keats' dreary poem Endymion.

Your author cannot warm to Keats – he considers him an inferior poet, a mere waffler, who picks up the attractive pebbles from here and there on the beach to stick on his wordy sand-castles; at a certain point in their lives, young bluestockings read him dreamily and young men attempting closer acquaintance with their stockings affect to be interested, too, but both put the book away when real life intervenes and things get serious.

In Book II of Endymion, Keats writes of 'fingers cool as aspen leaves':

O I do think that I have been alone

In chastity: yes, Pallas has been sighing,

While every eve saw me my hair uptying

With fingers cool as aspen leaves.

…

Endymion, Book II, 2.804.

Some may take this to be the usual empty waffle we expect from Keats; others may see some finely pointed irony such as 'fingers [that are trembling and definitely not as] cool as aspen leaves'. Foolish hope! The next lines dash any trace of ironic genius – this is just Keats babbling along, as usual:

… Sweet love,

I was as vague as solitary dove,

Nor knew that nests were built.

There are people who get excited at phrases such as 'fingers cool as aspen leaves' and 'vague as solitary dove'. Whatever turns you on.

In Book III Keats returns to the trembling aspen simile, this time using it according to tradition:

He spake, and, trembling like an aspen-bough,

Began to tear his scroll in pieces small,

Endymion, 3.746.

Keats trained as a medical doctor. It is no surprise, therefore, that from time to time that medical background emerges into his poetry.

One of these times occurs in Keats' description of the ancient Saturn in his unfinished poem, the dreary Hyperion (1818-1819), giving us our last Keatsian reference to the aspen. In 1817 James Parkinson had published his Essay on the Shaking Palsy, which we now know of as Parkinson's disease.

In his description of Saturn, the ancient king of the Titans, Keats transforms Parkinson's 'Shaking Palsy' into the new term 'aspen-malady':

Until at length old Saturn lifted up

His faded eyes, and saw his kingdom gone,

And all the gloom and sorrow of the place,

And that fair kneeling Goddess; and then spake,

As with a palsied tongue, and while his beard

Shook horrid with such aspen-malady:

Hyperion. A Fragment, 1.94.

Tennyson's aspen

Onwards. By the time the English trembling aspen has reached Tennyson's (1809-1892) safe pair of hands in his poem The Lady of Shalott, it has become just a bit of dreamy but skilfully executed background from the master of English mellow versification – meaninglessly pleasant – here in its two melodious versions:

1833 edition:

Willows whiten, aspens shiver,

The sunbeam-showers break and quiver

In the stream that runneth ever

By the island in the river,Flowing down to Camelot.

1842 edition:

Willows whiten, aspens quiver,

Little breezes dusk and shiver

Thro' the wave that runs for ever

By the island in the riverFlowing down to Camelot.

Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Lady of Shalott, 1833 and 1842 versions in comparison.

Sometimes they shiver, sometimes they quiver – that's aspen leaves for you. Here we encounter the reality of a poet whose only reality consists of the words he uses. Whether the object is 'sunbeam-showers' or 'little breezes' or 'streams' or 'waves' doesn't in the end matter – just paste the words together so they rhyme and create some hypnotic incantation.

The aspen in late summer. This view clearly shows the two trees of the cluster. After seeing the catkins in early spring we now know that the tree on the left is female and the one on the right is male. The trees that we see above ground arise from an extensive subterranean root system of this remarkable tree species. The trunks we see are in effect basal shoots put up by the root system. The Architect of the Universe has arranged things here so that the same subterranean structure puts up a male and a female tree. The land around the tree is intensively grazed and mown in summer, so it is unlikely that the aspen cluster will extend further. Its survival so far seems to be due to the rock outcrop on which it stands having protected it from human farming. The bitter bark and buds of the aspen protect it from damage by animals such as deer.– Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Seeking an exit

The reader would not forgive us if we were to set off now, trembling with deutsche Gründlichkeit, 'German thoroughness', on a comparison of the more recent usage of the trembling aspen in English and German. Our feeling is that the frequent occurrence of the cliché in German fairy tales kept the idea alive in the German consciousness in a way that did not happen in English. Let's leave it at that.

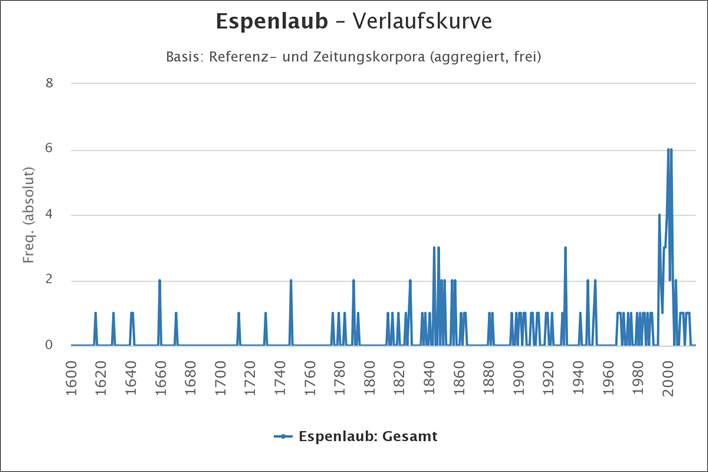

The absolute frequency of the occurrence of the word Espenlaub in all types of print media in German between 1600 and 2010.

Representations of word frequencies such as this have to be treated with caution: there are relatively few objects in the corpus from before 1900, whereas the massive increase in print media in recent times produces an opposite distortion. The only thing that can be said with some confidence is that aspen leaves have had a steady representation over the last two centuries in German. Most of these hits are associated with the property of trembling. The continuous low-level presence of Espenlaub for over two centuries points to the chewing gum stickiness of the cliché.

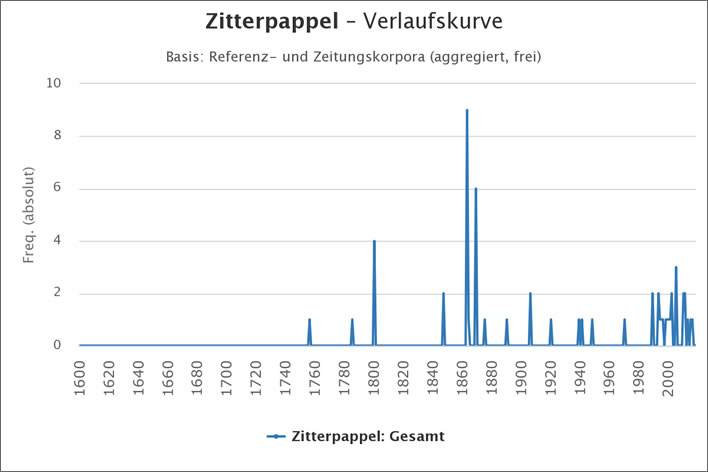

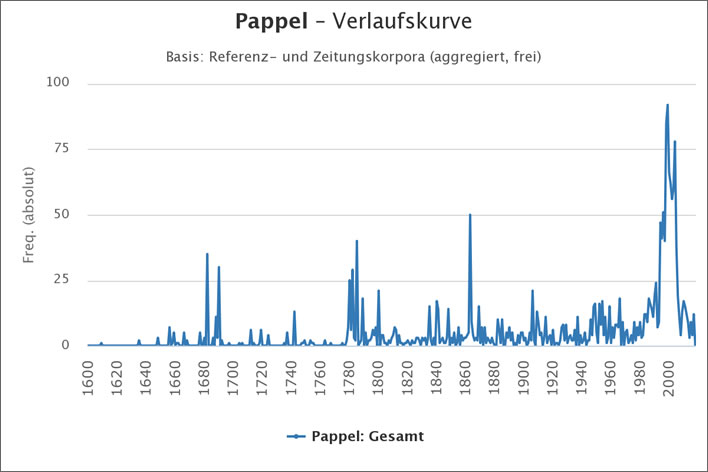

The frequencies of two related words for the same period, Zitterpappel, 'trembling poplar' (top) and Pappel, 'poplar' (bottom) show a loose correlation with Espenlaub. The marked peak in the 1860s can be explained by the publication of Emil Adolf Roßmäßler's forestry handbook Der Wald, 'the wood' in Leipzig in 1863. Images Verlaufskurven: Digitale Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache.

Perhaps a piece of music from the noble mind of Franz Schubert will distract us from that mountain of drudgery, for he, too, plays a part in our investigation.

The whispering aspen

'But', said the Chief Quality Assurance angel to the Architect of the Universe, 'There is still one small imperfection: in their trembling the leaves strike each other lightly – though not enough for damage – but it still appears to be a flaw.'

'That is' replied the Architect of the Universe 'not a bug, but a feature. From us, humanity gets the full package: in aeons hence lovestruck poets will stretch themselves out under the aspen and listen to the bewitching white noise of its trembling leaves. Who knows what they will come up with?'

The aspen in early summer, after the first haymaking. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Salis-Seewis' aspen

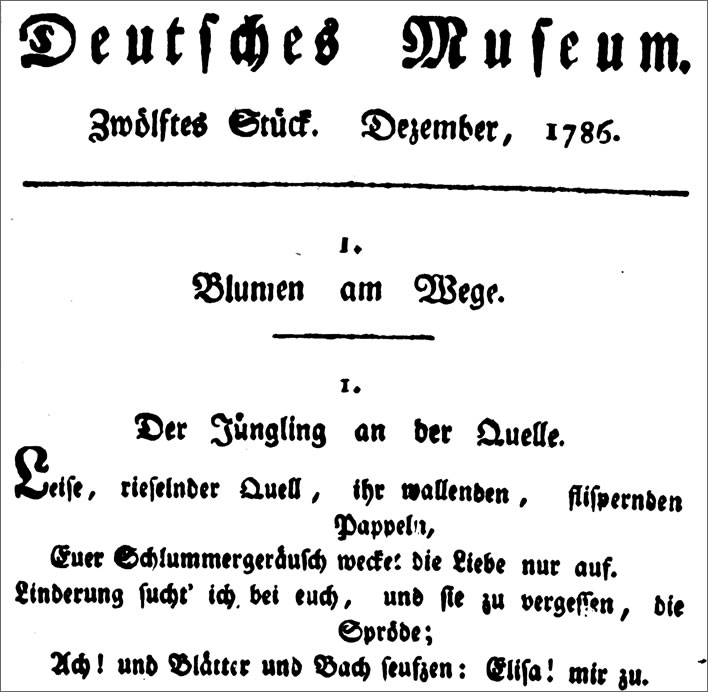

They will, for example, come up with the exquisite short poem Der Jüngling an der Quelle, 'The youth at the spring' by the Swiss aristocrat Freiherr Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis (1762-1834). This poem inspired Franz Schubert to one of his greatest song settings, D 300. The two masters, who never met each other, had a meeting of minds and the creative sparks flew. As was so often the case, Schubert's settings of Salis-Seewis poems saved yet another poet from literary oblivion.

Salis-Seewis, J.G.v, 'Der Jüngling an der Quelle' in Deutsches Museum, Blumen am Wege, 2.Bd., (1786), p. 481-483, p. 481. Image: Universität Bielefeld.

Salis-Seewis wrote few poems: he had a busy life full of military actions and great political events that was lived during the turmoil of the Napoleonic years in Switzerland. Der Jüngling an der Quelle is part of a small collection called Blumen am Wege, 'Flowers by the road'.

Unlike those endless professional scribblers Rochlitz and Rellstab, when, in his action-man life, Salis-Seewis got around to writing some poetry it was not earth-shaking stuff, no conventions were broken and no great poetic leaps forward were made, but what he wrote was finely crafted by a man – soldier, diplomat and administrator – who cared for language as an instrument of his profession.

Nor was he a poet who rapidly dashed off a poem and then moved on. One of the reasons his poetic output is relatively small compared to his other writings is that his poems went through a long period of maturation interrupted by frequent revision. The reader can assume that Salis-Seewis' texts are the carefully thought-out products of considered poetic intention.

Der Jüngling an der Quelle

The youth at the spring

Leise, rieselnder Quell,

ihr wallenden, flispernden Pappeln,

Euer Schlummergeräusch wecket die Liebe nur auf.

Linderung sucht' ich bei euch, und sie zu vergessen, die Spröde;

Ach! und Blätter und Bach seufzen: Elisa! mir zu.Softly trickling spring, you waving, whispering poplars, your soporific sounds just awaken my love. I sought relief here among you, in order to forget her, the unyielding one; Oh! and leaves and stream sigh Elisa! to me.

Freiherr Johann Gaudenz von Salis-Seewis, Der Jüngling an der Quelle, in 'Deutsches Museum', 'Blumen am Wege', 1786, p. 481.

Salis-Seewis calls the tree in his poem simply a Pappel, a poplar – how could a poet resist that plural Pappeln? But we know that he cannot mean the tall poplars which line roads – that would make no sense, for apart from roadkill, no one lies around under them. He surely means the Zitterpappel, the 'trembling poplar', a.k.a. die Espe, which we call the aspen.

That Salis-Seewis writes of Linderung, 'relief', 'comfort', 'amelioration' or simply 'healing' in association with the poplar is unlikely to be accidental, either – ointments and tinctures made from all the members of the poplar family have been used as remedies for many centuries. The tree bark and buds are a source of Salicin, the precursor of Aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), like the willow (Salix), which gave the compound its name.

Salis-Seewis, the soldier and man of the world, would have known this with near certainty, so that it is reasonable to see that this precise man's use of Linderung, in this case the relief of the pain of love, would be an allusion to healing that would be instantly recognisable by his contemporaries. His meditative, extended process of composition even leads us to expect to find such subtleties in his works.

Schubert's aspen

There have been few poets whose metrical and melodic sense has been the equal of that of Franz Schubert, the Liederfürst, the 'Prince of Song'. Schubert's setting of this poem is one that, once heard, is inseparable from the lyric, so precisely does he capture the metre and movement of the poem. Hands up – there is no shame in this – if you didn't realise that the poem is unrhymed. It is solely metre and rhythm.

It is thought that Schubert set the poem around 1816, during his young years of frantic song composition. It is just one more of those frustrations that litter Schubert's creative life that the song was not published until 1842, 26 years after he wrote it and 14 years after he died.

In the details of his setting of this poem Schubert changed Salis-Seewis' completely acceptable seufzen: Elisa! mir zu to the more polished seufzen, Luise, dir nach! In making this change, Schubert not only made the end of the poem more singable, he added the poetic logic for the echo-like repetition of the name at the end, a name now starting with a consonant.

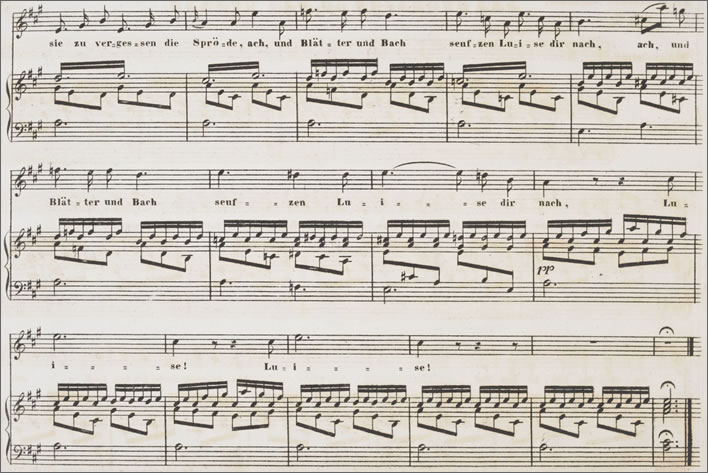

Or at least we think he made this change, for that is how it is reproduced in the first printed edition of the song – … ach, und Blätter und Bach seufzen Luise dir nach,:

D 300. D 301. D 736. Nachlaß 36. Heft. Franz Schubert's nachgelassene musikalische Dichtungen für Gesang und Pianoforte. 36te Lieferung. Der Jüngling an der Quelle. Lambertine. Ihr Grab. In Musik gesetzt für eine Singstimme mit Begleitung des Piano-Forte von Franz Schubert. Nachlass No 36. No 7414. Eigenthum der Verleger. Eingetragen in das Vereins-Archiv. (Gesang, Klavier.) Schubert, Franz, 1797-1828, Wien: Ant. Diabelli und Comp., [1842]. - 11 S. Image: ONB online.

This first edition was printed 14 years after his death: we do not know who wrote what in it and thus we shall never know Schubert's intentions, unless or until the manuscript turns up. It is currently in that familiar Austrian state: 'lost'.

Unfortunately, there are two downsides to this change. Firstly, the change damages the meaning of the poem. Salis-Seewis had the stream and poplars murmuring his loved one's name to him when he is trying to forget her, a situation that makes complete sense to the reader or listener.

The first printed version has the stream and poplars calling after the loved one, dir nach, on behalf of the poet as it were. This emendation throws away the core idea of the original, that the lovestruck young man came to the spring to forget about the girl, only to be reminded of her by the whispering of the stream and poplars.

This is not only quite a difference, it makes no sense at all. The poet wanted to forget die Spröde, this 'brittle', 'unbending' girl, not have her summoned to him. Schubert was probably not indifferent to this change of meaning, but he must have considered the euphonic advantages of dir nach over the weak mir zu to be worth the break.

However, dir nach has a further disadvantage that probably only the purist will notice: it creates an internal rhyme with both ach and Bach. Concluding an unrhymed poem with three internal rhymes on the trot just sounds odd.

Whichever version we take, more importantly, combined with the repetitions of the last line, Schubert caused the poem to end on a tone of rustling longing carried away on the wind. He had made the poem into a song, in other words, giving his singers and accompanists something to perform.

Or at least we think so – but as usual busy hands are at work on the composer's remains. By the time of Breitkopf und Härtel's 1893 edition the line has changed to …ach, und Blätter und Bach seufzen: Luise! mir zu,:

The change to mir zu, 'to me', has repaired the damage to the meaning of the original poem. It has, in fact restored Salis-Seewis' text, even down to the exclamation mark after Luise, but kept Schubert's change of name from Elisa to Luise. This is undoubtedly an improvement and should be taken as the canonical text for the song. It appears that we should credit the Austrian musicologist and composer Eusebius Mandyczewski (1857-1929) with this change.

Unfortunately, music publishers and performers have done their own thing with Salis-Seewis' last line. In his recordings Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau sometimes sings dir nach and sometimes even the odd hybrid Dir zu.

There is more confusion to come. According to Fischer-Dieskau, [Auf den Spuren der Schubert-Lieder, Brockhaus, Wiesbaden, 1971, p. 84.], it was the German musicologist and bass singer Max Friedlaender (1852-1934) who took it upon himself to replace Schubert's Louise with the generic Geliebte, 'loved one'.

Well, we all make mistakes, as we on this website know only too well, but only someone with a tin ear for language could propose this completely unnecessary change. With cutting Prussian politeness Fischer-Dieskau simply notes: man bleibt wohl besser beim Original, 'better to keep to the original'.

The aspen in late summer, a perfect place for a distraught young man to stretch out in its shade. Image: ©Figures of Speech – reuse only with a link to this page. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

The later Fischer-Dieskau singing a version with 'mir zu'. Impeccable, but for an unfortunate affectation on 'Pappeln':

The earlier Fischer-Dieskau singing a version with 'dir nach', but without the affected 'Pappeln':

A female voice for a change. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf singing (slowly but beautifully) a version with 'dir nach':

Heinrich Schlusnus, the singing postman, blowing the doors off the van in a version with 'Geliebte':

Update 28.09.2019

Added the aerial photo section on the age of our aspen.

Update 30.09.2019

Added some audio examples of performance variants.

Update 28.07.2025

A report in Live Science journal, 22.07.2025 (extracts):

Yellowstone's wolves are helping a new generation of young aspen trees to grow tall and join the forest canopy — the first new generation of such trees in Yellowstone's northern range in 80 years.

Gray wolves (Canis lupus) had disappeared from Yellowstone National Park by 1930 following extensive habitat loss, human hunting and government eradication programs. Without these top predators, populations of elk (Cervus canadensis) grew unfettered. At their peak population, an estimated 18,000 elk ranged across the park, chomping on grasses and shrubs as well as the leaves, twigs and bark of trees like quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides). This stopped saplings from establishing themselves, and surveys in the 1990s found no aspen saplings.

"You had older trees, and then nothing underneath," Luke Painter, an ecologist at Oregon State University and lead author of the new study, told Live Science.

But when wolves were reintroduced in 1995, the picture began to change. As wolf numbers rose, the elk population in the park dropped sharply, and it is now down to about 2,000.

The team returned to three areas surveyed in 2012 to examine changes to aspen sapling numbers. Of the 87 aspen stands studied, a third had a large number of tall aspen saplings throughout, indicating the trees are healthy and growing. Another third of the stands had patches of tall saplings.

"We're seeing significant new growth of young aspen and this is the first time that we've found it in our plots," Painter said. These are young aspen with a trunk greater than 2 inches (5 centimetres) in diameter at chest height — which haven't been seen there since the 1940s, he added.

The re-emergence of aspen has widespread effects, he told Live Science. "Aspen are a key species for biodiversity. The canopy is more open than it is with conifers and you get filtering light that creates a habitat that supports a lot of diversity of plants."

This means a boost to berry-producing shrubs, insects and birds and also species like beavers, because the trees are a preferred food and building material for the semi- aquatic rodents, along with the willows and cottonwoods that grow near to water in the region.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!