Alinde D 904: Rochlitz and Schubert

Richard Law, UTC 2018-12-03 13:12

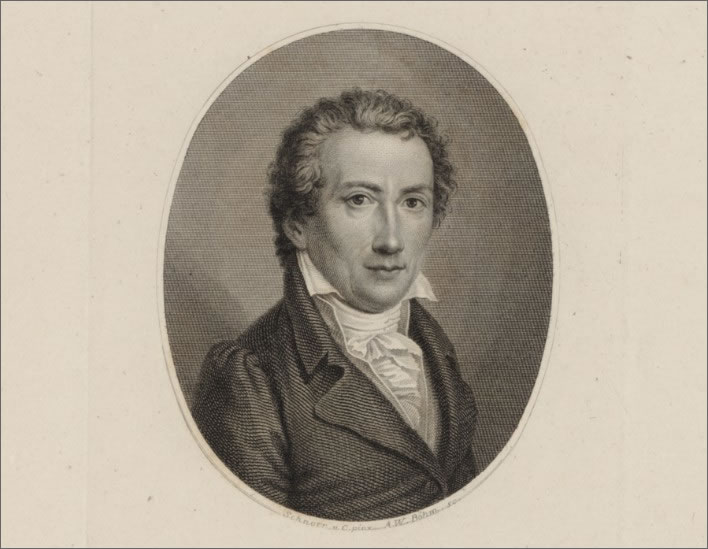

Johann Friedrich Rochlitz

Johann Friedrich Rochlitz (1769-1842) was, on the whole, a mediocre writer, a mediocre composer and a writer of evanescent music journalism.

The word 'mediocre' is not intended as an insult, just a statement of fact – for most of the artists of any particular age, the flint may be struck on the stone fiercely and often, but the sparks come seldom and the straw rarely ignites.

In contrast, when the genius – Goethe, Schiller, Schubert et al. – strikes, the sparks frequently fly and the tinder blazes bright, dazzling those around. As Yeats put it, using a related metaphor:

Some burn damp faggots, others may consume

The entire combustible world in one small room

As though dried straw…

W. B. Yeats, 'In Memory of Major Robert Gregory', from 'The Wild Swans at Coole' (1919) in Collected Poems, Macmillan, London, 1965, p. 151.

Rochlitz had one literary hit, an eyewitness account of the terrible Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig, the 'Battle of the Nations' in Leipzig in 1813. This engagement between the French and their allies and the coalition of Prussians and Austrians and their allies in its three days cost nearly 100,000 dead or wounded. British readers may recall Thomas Hardy's poem Leipzig (in Wessex Poems, 1898). The memory of that battle has disappeared in the modern age, written over by the great military-industrial massacres of the 20th century.

Johann Friedrich Rochlitz by Veit Hans Friedrich Schnorr von Carolsfeld, engraving by Amadeus Wenzel Böhm. c. 1823. Image: Gallica.

He inherited and married money, which allowed him to scribble away without striving. He befriended many of the literary and musical greats of his time, but at his death his damp kindling went out, never to light again. He and his works are nowadays as good as forgotten.

Except, that is, for three of his poems that came into the hands of Franz Schubert in 1827, and one of them in particular for which Schubert struck the flint true and the dry tinder of Rochlitz's verse caught fire. This is Rochlitz's poem Alinde, which Schubert set to music as Opus 81.1 (D 904).

Among the dross

Rochlitz published a first version of Alinde in 1805, in a book entitled Glycine (the botanical name for the soya bean – don't ask…). Rochlitz was around 36 at that time. The book contained a miscellany of short dramatic pieces, prose and poems, among which we find Alinde, well buried on page 223 (out of a total of 341 pages) – and this is only Part I of Glycine. Clearly, we are dealing with a top-notch scribbler here. Whether Alinde had appeared in some ephemeral publication previous to Glycine I do not know. It does not really matter. [Glycine 223]

Nearly 20 years of scribbling later we find Alinde once more, buried deep in volume four, page 153 of a six - six! - volume work entitled Auswahl des Besten aus Friedrich Rochlitz' sämmtlichen Schriften / Vom Verfasser veranstaltet, verbessert und herausgegeben, 'A selection of the best of Friedrich Rochlitz's collected writings / organized, improved and published by the author', published in 1822. Yes, these six volumes are just a selection from his collected scribblings – there would not have been enough paper in the whole of Saxony to publish the lot. [Selection 153]

It says something about Rochlitz's low status as a writer – he was around 53 years old by then – that he had to collect and publish his 'Selection' himself. Rochlitz had plenty of money, so our hard-hearted readers may suspect that the six volumes were not a commercial enterprise but simple vanity publishing.

Rochlitz revised Alinde for its appearance in the 1822 selection. Once more I have to confess that I have no idea whether the poem appeared anywhere else in the meantime or whether this was its only revision stage. Once more, it does not matter.

The way to Schubert

Eyelids droop and weariness creeps over us at the mere thought of the six volumes of scribbler Rochlitz's 'Selection' and the ghostly presence of the huge volume of the collected works which floats behind it. Yet we are shaken awake when we hear the year of the publication of the 'Selection': 1822. For that was the year that Rochlitz was hanging around in Vienna – 24 May to 2 August, Deutsch helpfully notes. [Dok 160]

Rochlitz, who idolised Beethoven, was hoping to get the chance to write a biography of the god. During this period he reported in a letter to his wife on 9 July 1822 that he had met Schubert. However, Rochlitz's account of that meeting lacks all credibility, for Otto Deutsch also. [Dok 159f]

It is unlikely that Rochlitz was handing out volumes of his newly published 'Selection' – although we have to admit that vanity publishers with money to burn are capable of anything. There may have been some contact with Schober during this time, or perhaps later when Schober was mixing in the literary circles of Breslau.

Perhaps Rochlitz's 'Selection' ended up in Schober's library, along with those famous poems of Wilhelm Müller, Die schöne Müllerin and Die Winterreise, all of them waiting for the genius to pick them up and make their authors immortal. Who knows?

But in January 1827, when Schubert set Alinde, he was living in the Schobers' apartment at Zum blauen Igel. It was an interesting and puzzling period in his life which we have discussed elsewhere. In the middle of all this complicated uncertainty, he composed the music for Alinde.

The setting

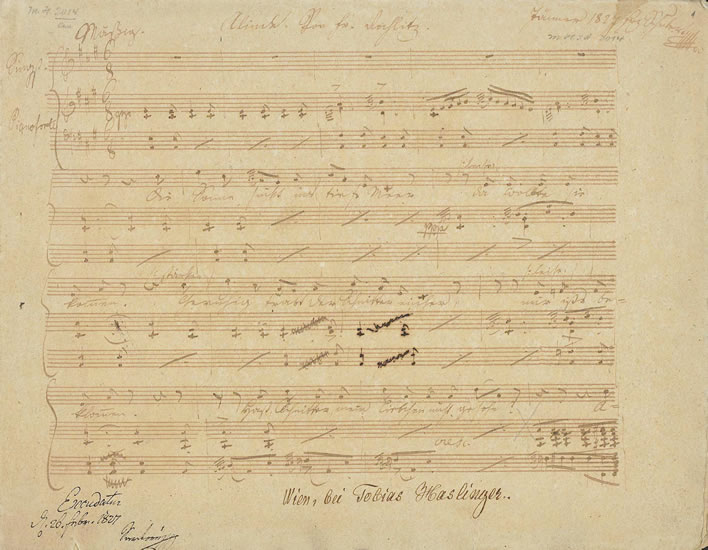

We can be certain of the date of composition of Alinde because we possess the manuscript, which is titled and dated in Schubert's hand: January 1827. Even better, the censor's written permission to publish is also on the manuscript, dated 26 February 1827.

Schubert autograph, page 1. Schubert's signature and the date is at the top right; the censor's permission, Excudatur, which Haslinger needed before he could set or print the work, is bottom left. Remember, we are under Emperor Franz's belljar: even the most innocent piece had to be signed off by the censor. Image: Schubert-Online.

By 28 May the three songs of Opus 81, of which Alinde was the first, were being advertised by Haslinger. [Dok 411 / 434]

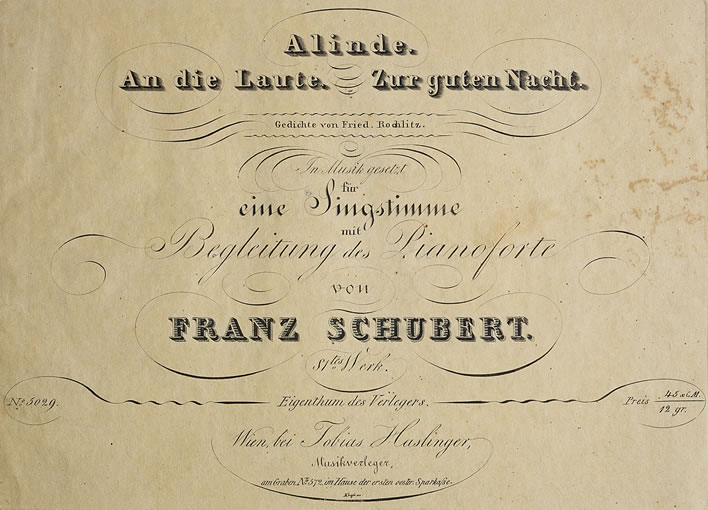

Title page, first print edition. Image: Schubert-Online.

Rochlitz's poem has all the components required for the romantic song: a rustic setting, three rustics pursuing their rustical trades, a boy and a girl and a very happy ending. The girl is always and totally in control of the situation, so the song can be considered a feminist narrative for the 1820s.

Wise musical heads can analyse the music – we, however, are going to play to our strengths and concentrate on Rochlitz's text. It may not be the greatest poem in the world, but it is workmanlike and deserving of a bit more attention than it usually gets when wrapped in Schubert's wonderful setting. It's not a deep or complex poem, its subtleties are all on the surface for those who choose to look.

Schubert made some small changes to Rochlitz's 1822 text. For our analysis we are going to take Schubert's text as written in his final autograph as definitive. At the end of the article there is a variorum text for the curious.

Alinde: text and translation

Die Sonne sinkt ins tiefe Meer,

Da wollte sie kommen.

Geruhig trabt der Schnitter einher,

Mir ists beklommen.

Hast, Schnitter, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?

Alinde! Alinde[!]

'Zu Weib und Kindern muß ich gehn,

Kann nicht nach andern Dirnen sehn;

Sie warten mein unter der Linde.'

The sun sinks into the deep sea. She said she would be here. The reaper lopes past calmly. I am so anxious. Have you, reaper, not seen my beloved? Alinde! Alinde! 'I have to go to my wife and children, I can't look for other girls. They're waiting for me under the lime tree.

Der Mond betritt die Himmelsbahn,

Noch will sie nicht kommen.

Dort legt der Fischer das Fahrzeug an,

Mir ists beklommen.

Hast, Fischer, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?

Alinde! Alinde!

'Muß suchen, wie mir die Reußen stehn,

Hab' nimmer Zeit nach Jungfern zu gehn.

Schau, welch einen Fang ich finde!'

The moon sets out on its path across the heavens. And still she's not here. There the fisherman lands his boat. I am so anxious. Have you, fisherman, not seen my beloved? Alinde! Alinde! 'I have to check my nets. I've no longer any time to chase after girls. Need to look what a catch I find!'

Berthold Genzmer, Abends bei den Reusen, 'Evening at the fishing nets'. Sometime before 1915. Image: photograph ©Andres Kilger, Nationalgalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin. Online.

Die lichten Sterne ziehn herauf,

Noch will sie nicht kommen.

Dort eilt der Jäger in rüstigem Lauf:

Mir ists beklommen.

Hast, Jäger, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?

Alinde! Alinde!

'Muß nach dem bräunlichen Rehbock gehn,

Hab nimmer Lust nach Mädeln zu sehn:

Dort schleicht er im Abendwinde!'

The bright stars ascend into the sky. And still she's not here. The hunter hurries along with a sprightly gait. I am so anxious. Have you, hunter, not seen my beloved? Alinde! Alinde! 'I have to follow the brown roebuck, I've no desire to look for girls. There he sneaks along in the evening breeze!'

In schwarzer Nacht steht hier der Hain;

Noch will sie nicht kommen.

Von allen Lebendgen irr' ich allein

bang' und beklommen.

Dir, Echo, darf ich mein Leid gestehn:

Alinde! Alinde!

'Alinde,'

ließ Echo leise herüberwehn;

Da sah' ich sie mir zur Seite stehn:

'Du suchtest so treu, nun finde.'

The grove is now in darkest night. And still she's not here. Of all living things I alone am wandering here, worried and anxious. To you, Echo, may I confess my suffering: Alinde, Alinde! 'Alinde,' Echo wafted faintly back. Then I saw her standing at my side. 'You have searched so faithfully, now find me.'

Rhyme scheme

The rhyme scheme of Alinde is remarkably simple – only two lines change their rhyme from stanza to stanza:

| Stanza 1 | Stanza 2 | Stanza 3 | Stanza 4 |

| Meer | Himmelsbahn | herauf | Hain |

| kommen | kommen | kommen | kommen |

| einher | an | Lauf | allein |

| beklommen | beklommen | beklommen | beklommen |

| gesehn | gesehn | gesehn | gestehn |

| gehn | stehn | gehn | herüberwehn |

| sehn | gehn | sehn | stehn |

| Linde | finde | Abendwinde | finde |

Structure

Alinde is also unusual for the very formulaic structure of the stanzas, each of which can be divided into three major sections.

Section 1

The first line of each stanza introduces a heavenly body, which, in turn, establishes a time point in the young man's lengthy wait for the girl to appear.

The second line in the first stanza establishes the arrangement ('she said she would be here') and in all subsequent stanzas is replaced by a single anxious and impatient formula 'still she's not here'. In the third line of the first three stanzas a rustic tradesman appears whose activity is related to that time point:

- Sunset, using the old poetic metaphor for the sun bathing in the distant ocean (e.g. in Goethe/Schubert Der Fischer, D 225). The reaper goes home in the twilight.

- Moonrise. The fisherman lands his boat.

- Starlight. The hunter pursues the nocturnal deer.

- Deepest night in the grove. No one around at all. The young man has not yet realised what the girl – careful of her reputation – must know: romantic trysts have to take place when no one else is around!

The fourth line of the first three stanzas is identical and only slightly changed in the fourth stanza. It is an expression of the young man's anxious state of mind.

The overall rhythmic structure of this section is worthy of notice. The first line lopes along, before it is nervously interrupted by an outburst expressing the young man's fragile state, almost as an aside. The third line picks up the rhythm again, only to be halted with another outburst of lover's Angst.

Section 2

The second section begins at the fifth line. In the first three stanzas it contains the questions directed by the anxious but incautious young man at the various tradesmen.

After posing each question, he calls out the girl's name twice. The repetition of the name is a master stroke that reflects all the uncertainty of the moment. In the fourth stanza, since no one else is around, the question is directed at the personification of Echo.

Section 3

The third section contains, in the first three stanzas, the response of the rustic person to the young man's question. All the rustics are going about their business and are no longer interested for their own various reasons in chasing after women.

In the final line each tradesman gives a pressing practical reason for the lack of help: the return to the family; the fisherman's need to empty his nets; the hunter's pursuit of the deer. In the last stanza, the girl delivers the response to his calls herself.

The rustic Romantic

Despite the rather impolite things we said about Rochlitz in our introduction, we have to admit that his various conceits in Alinde in skill and inventiveness go well beyond the mediocre: the figures of rustic tradesmen – reaper, fisherman and hunter; the natural settings – field, lake, wood and grove; the language, which through the use of so much direct speech remains relatively close to the spoken language of the people. We even encounter that must-have staple of all ethnic German longings, the Lindenbaum, the lime tree. Winterreise fans will be nodding their heads, as will attentive readers of our piece on Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart.

We recall that Clemens Brentano und Achim von Arnim had published the first volume of their collection of (largely fake) 'folk poems', Des Knaben Wunderhorn in 1806. That publication is held to be the opening shot in the Romantic battle to reinstate the validity of folk poetry after the classicism of the 18th century writers in German.

We recall that Alinde was also first published in book form in 1805. A Romantic rusticality that brought a political return to German roots was in the air and Rochlitz was one of the many who breathed it in. Alinde's use of formulae, its spoken language, its figures, its settings, is well ahead of nearly all the the works in Des Knaben Wunderhorn.

Metrics

Now that everyone agrees that Alinde is remarkably formulaic and structurally homogenous the question presents itself – if that is so, why did Schubert need seven pages of manuscript score to write the song?

The answer is obvious when we look at the erratic metrical structure within the lines. To see just how erratic it is, let's compare the lines from particular positions in each stanza.

Line 1

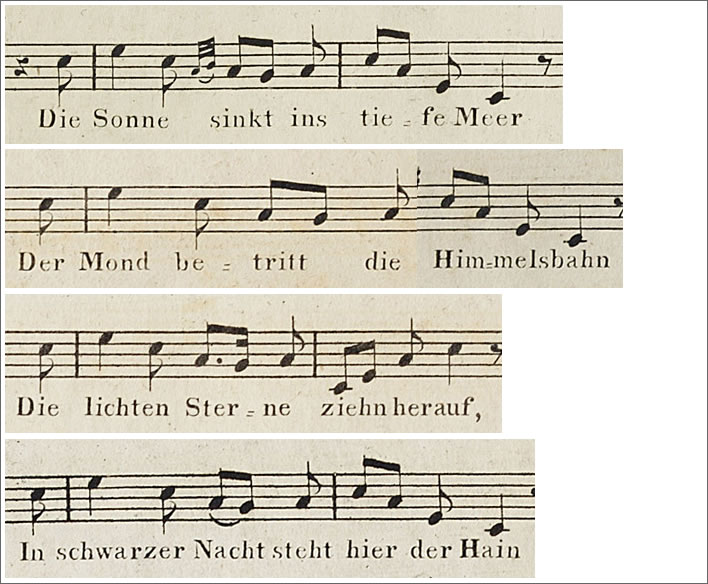

Here are all the first lines. The syllables marked in blue represent stressed (or long) vowels:

| Die | Son | ne | sinkt | ins | tie | fe | Meer |

| Der | Mond | be | tritt | die | Him | mels | bahn |

| Die | lich | ten | Ster | ne | ziehn | her | auf |

| In | schwar | zer | Nacht | steht | hier | der | Hain |

We can see at a glance that the first lines are completely regular amongst themselves. The lines are iambic tetrameters with an identical syllable count and identical stressing. The springing rhythm of the iambic tetrameter is a characteristic of the stressed metre: Schubert did not have far to look to find the loping rhythm that underlies his setting.

However Schubert, aware of the freeform aspects of Rochlitz's text that we shall meet in a moment, turned the springing rhythm into – how can we describe this? – a fluid, sensuous musical line. Rochlitz's four regular first lines were anything but regular in Schubert's hands:

The eight syllables of the first line are rendered in a vocal line of 12 notes, musical metaphors focused on sinkt and tiefe. In the second line the two stressed syllables -tritt and Him- are given two notes each – a pattern that is repeated in the first line of the fourth stanza. In the first line of the third stanza, ster- and ziehn get the same two-note treatment – quite amusing really, since Rochlitz used the single syllable ziehn, the elided form of the two syllable ziehen in order to get the metrics right; Schubert effectively reinstates the two syllables to get the slithering effect of the music. The melody of this line is also substantially different from the other three: presumably to create the musical equivalent of the text ziehn herauf, 'ascend', Schubert's melody also ascends, whereas that of the other three lines descends.

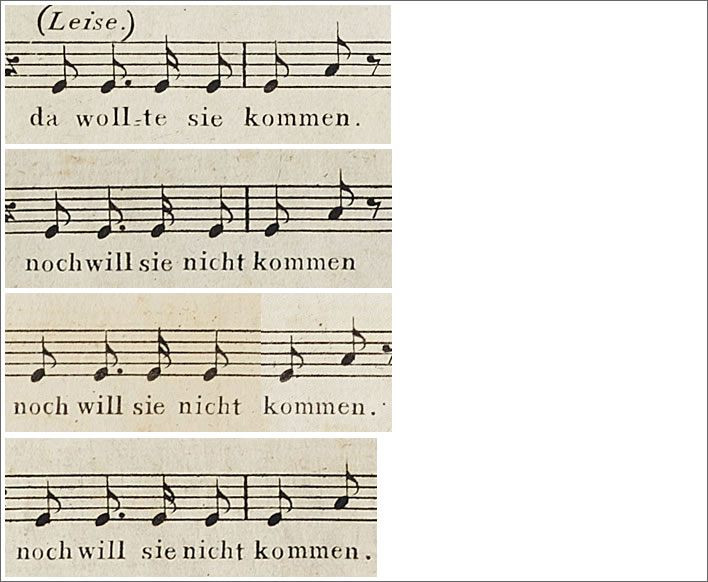

Line 2

| Da | woll | te | sie | kom | men |

| Noch | will | sie | nicht | kom | men |

The two variants of the second lines are also regular. The metrical form now interrupts the loping rhythm with a burst of anxiety.

Schubert left these formulaic text lines as completely regular vocal lines – one syllable, one note. He was right to do this, whether by instinct or cunning: these lines are a repeated expression of anxiety on the young man's part and such decoration would have been out of place. The rising tone at the end of each statement would be found in spoken German as an expression of frustration or impatience. As usual, Schubert's ear for the spoken language is impeccable. Alinde is, of course, entirely spoken.

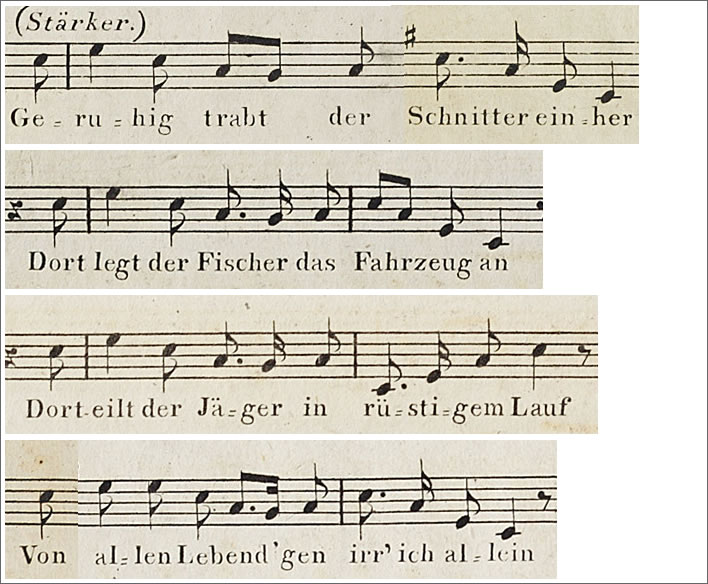

Line 3

| Ge | ru | hig | trabt | der | Schnit | ter | ein | her | ||

| Dort | legt | der | Fisch | er | das | Fahr | zeug | an | ||

| Dort | eilt | der | Jä | ger | in | rüst | i | gem | Lauf | |

| Von | al | lem | Le | bend | gen | irr' | ich | all | ein |

The third line presents us with a metrical challenge.

Klopstock, Haller, Goethe, Schiller and Co. would have found these lines reprehensible, with sometimes nine, sometimes ten syllables and apparently erratic stressing, but the age had changed and poetry with it. We have moved from the imitation of Classical metrics based on vowel length to stressed German based on speech. Not quite the speech of the common people, because that would have been in a dialect that no one else understood, but a slightly sanitised form with many of the properties of dialect speech.

This is not the 18th century but the first decade of the 19th. Napoleon Bonaparte was trampling over the statelets of German territory essentially unopposed. Rochlitz and many other writers rediscovered the German people, German cultural solidarity, German speech and German honesty. Pindaric odes and all the other Classical clutter were out, together with imitations of French and Italian poetry. The rhythms of German speech were definitely in.

In Alinde, as in normal speech, there are not just stressed and unstressed vowels, long and short vowels, but there is a spectrum of weights and lengths in between. There are degrees of length in Classical metrics, but only for professors; schoolchildren must be content with binary lengths. In contrast, the modern spoken languages of Europe have lengths and weights on analogue scales. Almost any message thread on any social medium will deliver just sooooo many examples of the written forms of the new oralism. If only Rochlitz had had emojis –noch will sie nicht kommen / bang und beklommen etc. etc.

For someone we characterised as 'mediocre', his handling of these forms displays great metrical sensitivity and a good ear. Rochlitz may have been a mediocre musician, but like Schubert, he had a fine ear for speech rhythms.

He gets away with these irregularities in Alinde because he utilises the elisions present in natural, spoken German. We say it again: Alinde is speech, partly as an anxious monologue and partly as dialogue. Von allen Lebendgen irr' ich allein is a good example. A strict syllable count yields a total of ten syllables, one more than the usual nine, but this extra syllable could disappear very easily in many of the possible elisions.

Schubert, even more sensitive than Rochlitz to the exigencies of spoken rhythms, bravely changed Rochlitz's elided rüstgem into the full rüstigem.

A native speaker, particularly one with a dialect basis, would rattle along these lines and find nothing unexceptional in them. Welcome to the new age of German poetry!

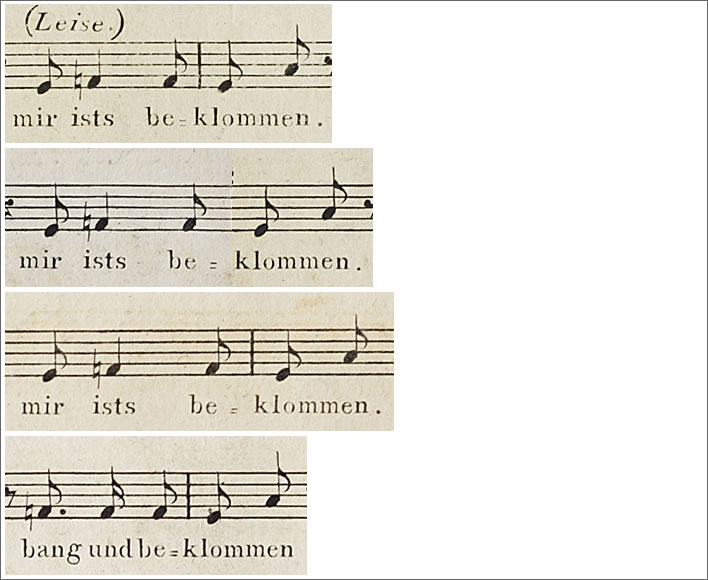

Line 4

| Mir | ists | be | klom | men |

| bang | und | be | klom | men |

As in the previous expression of the young man's anxiety, the change of metre retards the loping rhythm. This produces a metrical caesura that marks the change from internal monologue to direct speech for the formulaic question for the tradesman. It is also one more indicator of the 'rough', natural speech so sought after by the folk poetry movement.

The four lines are undecorated and almost identical. 'Almost', that is, except for the slight changes to give the word bang– really bange– 'anxious, uneasy, alarmed', its due emphasis. These phrases are yet further examples of Rochlitz's skilful handling of spoken German and Schubert's even more skilful transposition of the spoken language into music.

Notice, for example, how Schubert stretches and sharpens the note on bang in order to reflect this important change to the formula for the last stanza. He was not called the Liederfürst for nothing.

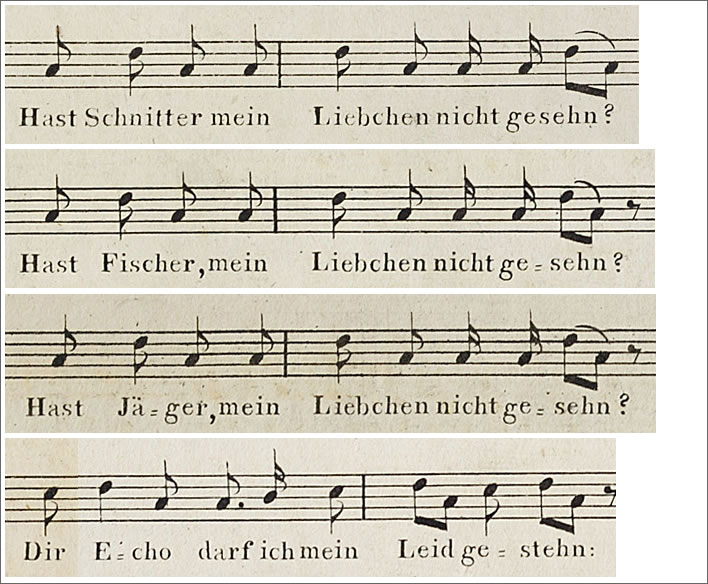

Line 5

| Hast | Schnit | ter | mein | Lieb | chen | nicht | ge | sehn |

| Hast | Fi | scher | mein | Lieb | chen | nicht | ge | sehn |

| Hast | Jä | ger | mein | Lieb | chen | nicht | ge | sehn |

| Dir | E | cho | darf | ich | mein | Leid | ge | stehn |

The metrical form of the questions in the first three stanzas is identical. The line in the fourth stanza differs, however, in that the question to the personified Echo is less direct than those to the tradesmen.

The first three occurrences of these lines are also musically identical. We note however that Schubert has taken yet another one of Rochlitz's contracted forms gesehn and expanded it with an extra note to restore the full form gesehen.

The fourth line is adapted to respect the changed context of the personified Echo as a dialogue partner and express the particular pain of Leid with two notes. The elided form gestehn is also unpacked with an extra note to form gestehen.

Line 6

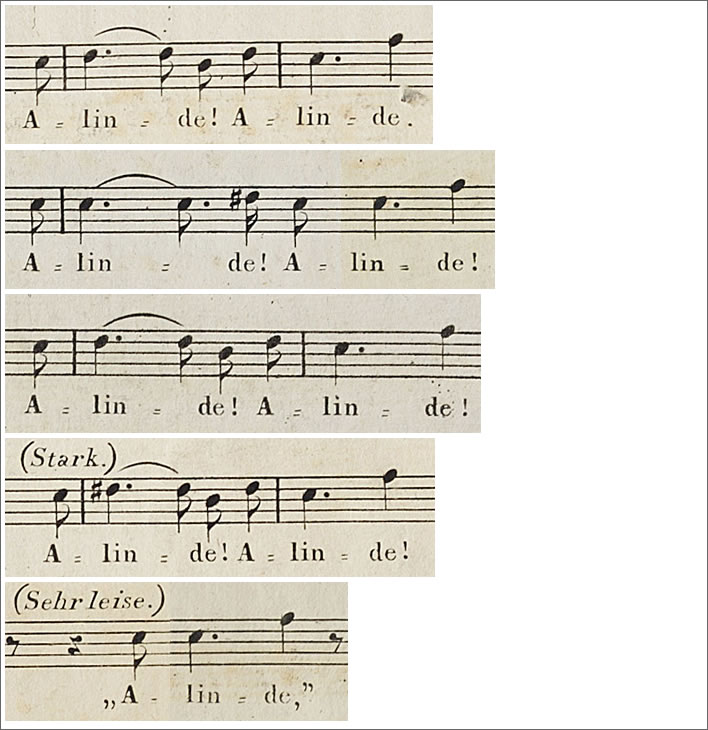

| A | lin | de | A | lin | de |

After putting his question to the tradesmen, the young man calls out the girl's name twice. In the last line, when the young man speaks to Echo, Rochlitz adapted the line slightly. The second cry of Alinde was inserted in quotation marks after a long dash, representing the response of Echo.

Schubert quite rightly decided to have nothing to do with that fudge – after all, you can't sing quotation marks. He left the young man's two cries as in the previous lines, thus achieving consistency, and added Echo's response cleanly on the next line, marking it sehr leise, 'very quiet'. Rochlitz's fudge was not needed and Schubert created a moment of quiet, singable drama in the narrative of the song. There is a brief wait before Echo's response is heard and a brief wait afterwards, before the music lopes down to the resolution. At this moment, no one is counting lines or syllables. Happy the poet, whose work gets set by Schubert!

Line 7(8)

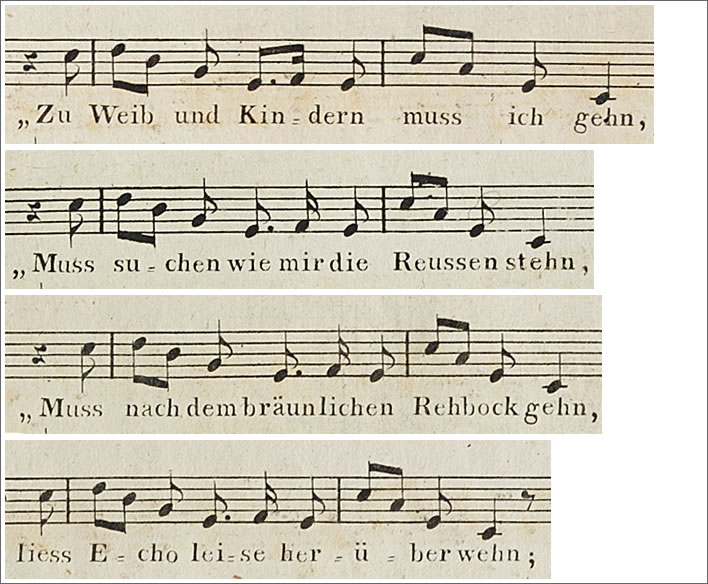

| Zu | Weib | und | Kin | dern | muß | ich | gehn | ||

| Muß | su | chen | wie | mir | die | Reu | ßen | stehn | |

| Muß | nach | dem | bräun | li | chen | Reh | bock | gehn | |

| ließ | E | cho | lei | se | her | ü | ber | wehn |

The irregular line from the first stanza, with only eight rather than nine syllables, is an improvement made by Rochlitz. In his first printed version of the poem from 1805 the reaper was returning Zur flinken Schnitterin, 'to the lively female reaper', which would have matched metrically with nine syllables all the other instances of this line: Zur-flin-ken-Schnit-te-rin-will-ich-gehn.

But since the tradesmen also appear to represent life stages, the waiting wife and family fit in better with the narrative than a 'lively girl'. The young man and his Alinde represent the first moment in a generational arc that passes through the life stages of the tradesmen mentioned here.

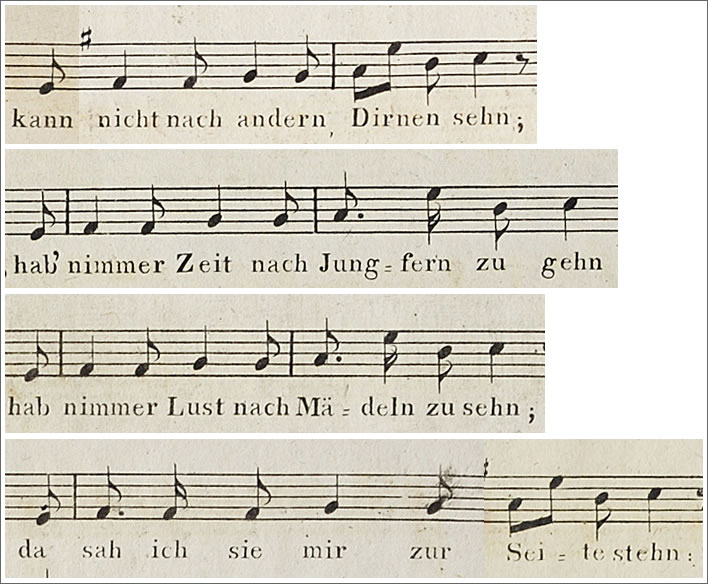

Line 8(9)

| Kann | nicht | nach | an | dern | Dir | nen | sehn | ||

| Hab' | nim | mer | Zeit | nach | Jung | fern | zu | gehn | |

| Hab | nim | mer | Lust | nach | Mä | deln | zu | sehn | |

| Da | sah' | ich | sie | mir | zur | Sei | te | stehn |

Our presumption of life stages is supported by the language used by Rochlitz when the tradesmen deliver their excuses. The reaper is bound by family obligations not to go chasing after girls; the fisherman no longer has time; the hunter no longer has lust.

These statements in the second and third stanzas are identical. Those of the first and fourth stanzas are almost identical, apart from small differences caused by the metrical specialities of the fourth stanza.

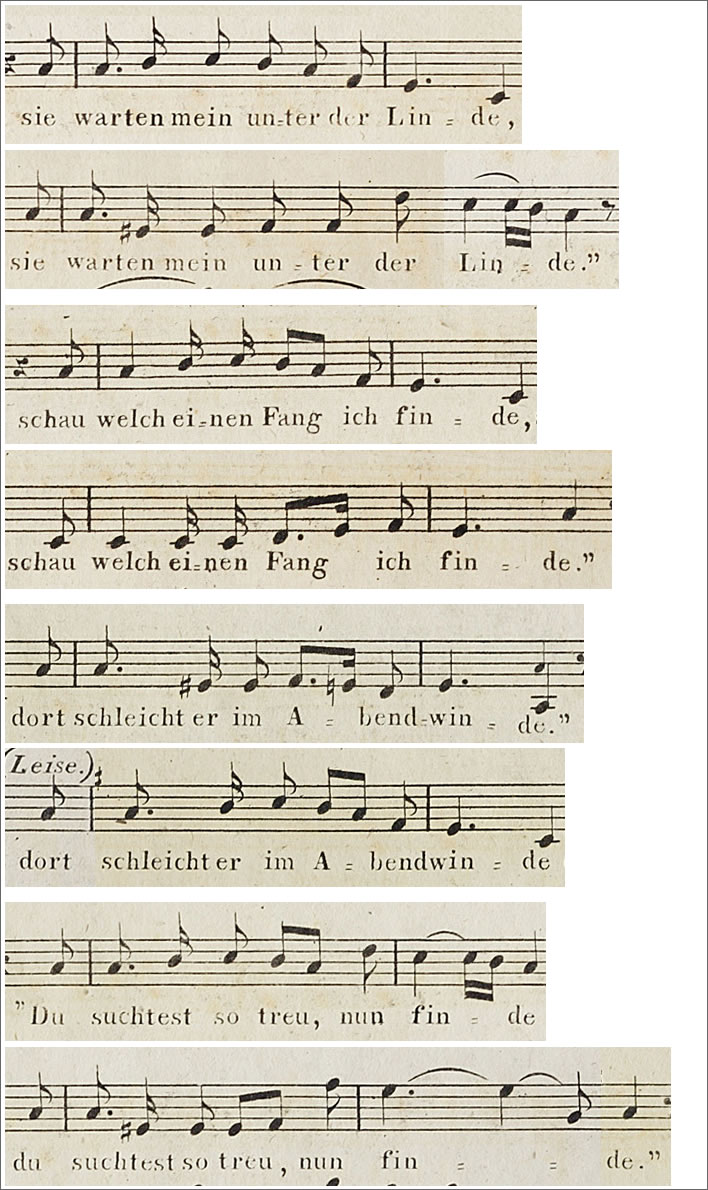

Line 9(10)

| Sie | war | ten | mein | un | ter | der | Lin | de |

| Schau | welch | ei | nen | Fang | ich | fin | de | |

| Dort | schleicht | er | im | A | bend | win | de | |

| Du | such | test | so | treu | nun | fin | de |

Schubert has responded to Rochlitz's erratic metre and the exigencies of the situation. He has repeated the final line in some variant; each example is similar but different in a number of ways. He has added notes to compensate for the erratic metre of the text: Lin-, Fang- and treu are metrically rescued with added notes.

Magisterial judgement

Alinde is a remarkable poem in many ways. It displays a great metrical flexibility within a framework of formulaic dialogue. It also displays all the characteristics of the new age of folk poetry then in vogue.

It is a well constructed poem. Just because Rochlitz's overall poetic output is unimpressive, we should not dismiss a good piece such as Alinde out of hand. Rochlitz also improved the 1805 version appreciably for the publication in 1822.

Schubert turned it into an even more remarkable song. He showed great discernment in seeing the musical opportunities the poem offered. His setting made full use of the metrical flexibility of the poem, forcing him to compose a setting over seven pages.

Because of Rochlitz and Schubert's subtleties, performing Alinde is a challenge for any singer.

Reception

Now we have looked at Rochlitz's text and Schubert's music in some detail through our modern eyes, the responses of the music critics of the time are interesting.

Munich

Otto Deutsch reproduces the perceptive and positive comments of the correspondent of the Munich Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung that appeared on 6 October 1827:

The first of the poems [Alinde] is not intended to be a song and thus, quite rightly, has been given a more comprehensive musical treatment. This is, however, so characterised and original, that we could recommend the Opus to the friend of song, even if the song that follows it [An die Laute] were not as successful as it in fact is. The least unusual is No. 3 [Zur guten Nacht], which, irrespective of that, has a very pleasant effect.

Das erste der Gedichte ist nicht als Lied gedacht, daher mit allem Recht auch etwas höher gehalten in der musikalischen Ausführung. Diese aber ist so charakteristisch und originell, daß wir das Werkchen schon darum den Freunden des Gesangs empfehlen könnten, wenn auch das darauf folgende Lied, an die Laute, weniger gelungen wäre, als es der Fall ist. Am wenigsten eigentümlich ist Nro. 3, aber demungeachtet auch von ganz allerliebster Wirkung. [Dok 455f]

Deutsch remarks on the author's odd characterisation of Rochlitz's text as 'not intended to be a song' and correctly attributes this to the erratic metrics of the poem.

Leipzig

In the Leipzig Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung of 23 January 1828, Schubert's Opus 79, 80 and 81 received a long and very positive review. This, of course, was the journal that Rochlitz had co-founded in 1798 and edited from then until 1818. Of Alinde in particular, the reviewer says perceptively:

Opus 81. The poems by Herr Rochlitz, very well chosen. Although they are similar in clarity of expression and the natural representation of the inner life, which is what musical poetry should always be, they differ substantially in their true characteristics. The first [Alinde] is humorously serious, the second charmingly tender and the third soulfully sincere and profoundly moving.

The first poem was not easy to treat musically. It contains exactly corresponding stanzas: in which case, one would expect, each one would have the same music. At the same time these are dialogues, to some extent dramatic scenes: in which case the very contrasting dialogue partners should also be represented in very different, contrasting ways. At the same time the tone and register of the language is quite simple: in which case the music also has to be like that. Herr Schubert has treated it in exactly that way. In order to achieve the first requirement, the stanzas are all individually composed with some deviations: however only small and not disturbing.

81stes Werk. Die Gedichte von Fr. Rochlitz, sehr gut gewählt. So ähnlich sie auch einander in Klarheit des Ausdruckes und in natürlicher Darstellung des innern Lebens sind, was musikalische Gedichte immer sein sollten: so unterscheiden sie sich doch auch wieder hinlänglich durch ihr treu Charakteristisches. Das erste ist scherzhaft-ernst, das zweite lieblich-zart und das dritte seelen-innig und tief ergreifend. Das erste war nicht leicht musikalisch richtig zu behandeln. Es ist in genau einander korrespondierenden Strophen: so mußte auch jede die selbe Musik bekommen. Diese sind aber dialogisch, ja gewissermaßen szenisch: so mußten zugleich die sehr verschiedenen, einander entgegengesetzten Sprecher zugleich sehr unterschieden, einander entgegengesetzt werden. Gleichwohl ist Sprachton und Haltung ganz einfach: so mußte es auch die Musik bleiben. Hr. Sch. hat es wirklich so behandelt. Das erste anlangend, so sind zwar die Strophen sämtlich ausgesetzt, und einige Abweichungen finden sich: doch nur kleine, nicht störende. [Dok 483]

Schubert here had good and fair reviewers, both of whom saw the challenge of Rochlitz's text and appreciated Schubert's success in rising to that challenge. It is fair to say that Schubert set a memorial to Rochlitz – as he did with so many of the poets he set to music – that would endure when the poet's six volume 'Selection' would be dust on the few library shelves which stocked it.

Vienna

In Munich and Leipzig Alinde received good, perceptive and relatively prompt reviews – 'prompt' in this case being a euphemism for 'whilst the composer was still alive'. What about in Austria, the 'land of music'?

As far as I can tell the only review came after the composer had been safely decomposing in hole no. 323 in the Matzleinsdorfer Friedhof for about six months. It was a brief notice in the Allgemeiner Musikalischer Anzeiger for 16 May 1829:

Alinde is very pleasing, full of freshness, attractive intimacy and exceptional melody; the speakers introduced into the poem are very distinct from the lyrical outpourings of the lover and the whole is a great success. The second song, and die Laute, is a clever trifle. The third, zur guten Nacht, seems to us to be too earnest, too stiff and, because of the identical structure of the musical phrases, too uniform.

Alinde is sehr ansprechend, voll Frische, reizender Innigkeit und besonderer Melodie; die im Gedichte redend eingeführten Personen sondern sich scharf von den lyrischen Ergüssen des Verliebten und das Ganze ist höchst gelungen. Das zweite Lied: an die Laute, ist eine artige Kleinigkeit. Das Dritte zur guten Nacht, dünkt uns zu ernst, zu steif und wegen des gleichen Baues der musikalischen Perioden zu einförmig. Anno.

The last word can go to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who is as dismissive as we are about Rochlitz's poetic talents and damns with faint praise the result produced by Schubert. He is writing nearly a hundred and fifty years after the previous reviewers, by which time Rochlitz's reputation has completely fizzled out:

ALINDE, the story of a rendevous almost gone wrong, is based on the somewhat weak idea of the less than convincing poet…

In ALINDE Schubert adapted the music to the text in an undemanding way and achieved a charming effect, in which the barcarole tone recalls that of the FISCHERMÄDCHEN.

ALINDE, die Geschichte von einem fast verunglückten Stelldichein, gründet sich auf den etwas schwachen Einfall des wenig überzeugenden Dichters… In ALINDE paßt Schubert mit geringfügigen Änderungen ganz anspruchslos die Strophen dem jeweiligen Text an und erreicht charmante Wirkung, wobei der Barkarolenton ein wenig an das FISCHERMÄDCHEN erinnert.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Auf den Spuren der Schubert-Lieder, Brockhaus, Wiesbaden, 1971, p. 279f.

Despite Fischer-Dieskau's dismissive opinion of Rochlitz – the 'less than convincing poet', the 'weak idea' of his poem Alinde and his characterisation of Schubert's setting as 'undemanding' – through a sensitive and precise reading Fischer-Dieskau delivered a fine interpretation. The final effect is indeed charming, but getting from Rochlitz's text to the charm of the song was anything but undemanding for Schubert.

With Alinde, Rochlitz's flint struck a spark, but it was Schubert's melodic and interpretative genius that caught that spark, now long extinguished, and turned it into the bright flare that still startles us today.

Alinde : variorum 1805, 1822, 1827

The base text is Schubert's 1827 version of the poem. Text highlighted in blue is a variant from Rochlitz's 1822 text (that is, amended by Schubert). Text highlighted in green is a variant from Rochlitz's 1805 text (that is, amended by Rochlitz). Hover the cursor over the highlight to see a tooltip containing the previous text.

Die Sonne sinkt ins tiefe Meer,

Da wollte sie kommen.

Geruhig trabt der Schnitter einher,

Mir ists beklommen.

Hast, Schnitter, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?

Alinde! Alinde.

'Zu Weib und Kindernmuß ich gehn,

Kann nicht nach andern Dirnen sehn;

Sie warten mein unter der Linde.'

Der Mond betritt die Himmelsbahn,

Noch will sie nicht kommen.

Dort legt der Fischer das Fahrzeug an,

Mir ists beklommen.

Hast, Fischer, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?

Alinde! Alinde!

'Muß suchen, wie mir die Reußen stehn,

Hab' nimmer Zeit nach Jungfern zu gehn.

Schau, welch einen Fang ich finde!'

Die lichten Sterne ziehn herauf,

Noch will sie nicht kommen.

Dort eilt der Jäger in rüstigem Lauf:

Mir ists beklommen.

Hast, Jäger, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn?

Alinde! Alinde!

'Muß nach dem bräunlichen Rehbock gehn,

Hab nimmer Lust nach Mädeln zu sehn:

Dort schleicht er im Abendwinde!'

In schwarzer Nacht steht hier der Hain;

Noch will sie nicht kommen.

Von allen Lebendgen irr' ich allein

bang und beklommen.

Dir, Echo, darf ich mein Leid gestehn:

Alinde! Alinde!

'Alinde,'

ließ Echo leise herüberwehn;

Da sah' ich sie mir zur Seite stehn:

'Du suchtest so treu, nun finde.'

Note on line 5: The only gramatically correct orthography for the four questions at line 5 requires commas around the name of the addressed, for example, Hast, Schnitter, mein Liebchen nicht gesehn? Schubert, son of a Jesuit-educated schoolmaster and himself a Piarist-educated assistant teacher, knew this and set commas correctly – albeit sometimes faintly – in the autograph. Haslinger's printer left us the chaos: Hast Schnitter mein | Hast Fischer, mein | Hast Jäger, mein | Dir Echo darf.

Sources

All sources are in German, unless otherwise noted. All translations ©FoS.

| Dok | Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Dokumente Seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. [DE] |

| Glycine | Rochlitz, Friedrich. Glycine, Darnmann, Züllichau, Part 1, 1805. [DE] Online. |

| Selection | —. Auswahl des Besten aus Friedrich Rochlitz' sämmtlichen Schriften, Darnmann, Züllichau, Volume 4, 1822. [DE] Online. |

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!