Fresh air, 1779

Richard Law, UTC 2017-05-15 18:46

Buried alive

In this cell there was a small gap in the wall underneath the stove, through which he and the man in the cell on the other side of the wall could speak. His neighbour was Herr von Scheidlin, a member of a well-placed family in Augsburg. He was already in his nineteenth year of imprisonment on Hohenasperg, being 'buried alive' there in 1759 on the secret orders of Carl Eugen, acting on the request of Scheidlin's brother who, because of some family dispute, wanted him out of the way. [Leben 2:237]

Scheidlin would be 'buried alive' in Hohenasperg for 28 years altogether. Unlike Schubart, Scheidlin was not being re-educated, just deprived of his liberty, so he had some home comforts that Schubart did not. Considering the length of Scheidlin's stay on Hohenasperg we might come to the conclusion that Schubart got off lightly with his ten years there.

They soon established communication: Schubart would lie on a mattress on the floor 'in the Turkish manner', Scheidlin would pass beer and a pipe of tobacco through the hole (Schubart was a passionate smoker) and then settle down on the ground on his side of the hole. Apart from the shared experiences of their imprisonment they had many shared literary and musical interests and so quickly became firm friends. They were like 'strings tuned to the same note that resonated with each other' as Schubart put it. At last he had a friend to whom he could speak openly, a genuine human being, in contrast to the very guarded exchanges with his spiritual tormentors. [Leben 2:318n]

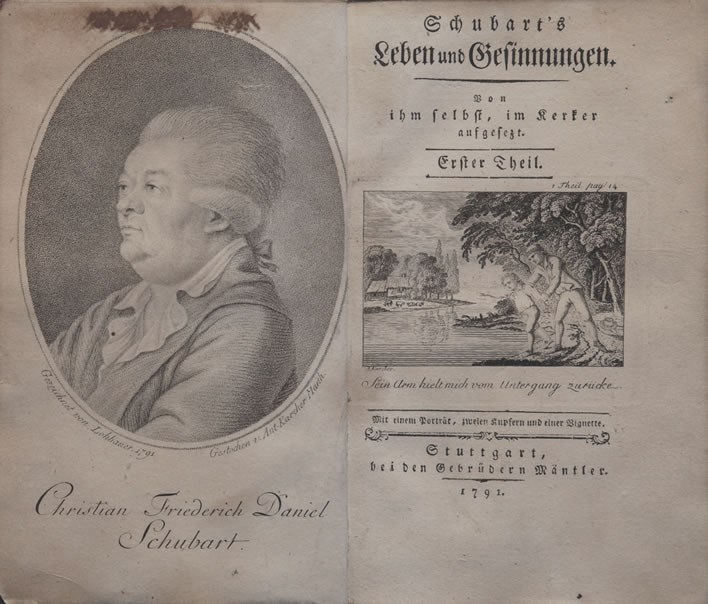

Schubart was still not allowed to write, so he began to dictate what was later to be published as his autobiography, Schubart's Leben und Gesinnungen, 'Schubart's Life and Opinions', to Scheidlin through the hole. Scheidlin sat on the ground on the other side of the wall, manuscript resting on a wooden stool, and took down the first draft of the book. [Leben 2:237]

The frontispiece and title page of part 1 of the first edition of Schubart's autobiography Schubart's Leben und Gesinnungen, 'Schubart's Life and Opinions', published in 1791, the year of his death.

Despite his new-found friendship, Schubart found the autumn of 1778 particularly hard to bear. His physical problems exacerbated the weaknesses of his mental state and led him into a deep depression. 'Every falling leaf of the lime tree in front of my window reminded me of my death.' [Leben 2:245]

Although death itself had lost many of its terrors, the deep human fear of dying was still present. Winter came and twelve or more hours of frosty darkness wrapped around him. He imagined that earthly winter in Hohenasperg as a foretaste of what awaited him in the afterlife, when he would surely be thrown into the outer darkness with wailing and chattering of teeth at the unbearable cold. 'O God', he would pray, 'out of the dungeon and into the dungeon – save me from this fate!' [Leben 2:247-9]

Hahn the preacher visited him on 14 November. The latter recommended a spiritual diet: morning and evening prayers, morning and afternoon bible reading, abstinence from alcohol. [Leben 2:269-283] According to Schubart's own account, the abstinence he felt most keenly was from women:

Nothing was harder for me to counter than the love of the fair sex. Because I had had this trait from youth and had not resisted, holding it to be just a pleasant weakness, it became second nature to me. I had the feeling that this tendency could not be purged without destroying my whole being. I occasionally saw female faces and felt how lust came upon me and my heart pressed.…

Prayer is the only remedy … and chastity becomes easier for me every day. The immanent presence of the purest being; that thundering phrase: 'Outside are the dogs!' and the observation that the difference between the sexes will disappear in that presence have a deep effect on me.

Leben 2:229f.

A walk in the open air

1778 finally passed. On 1 February 1779 Carl Eugen visited Hohenasperg and allowed Schubart to attend the public service in the fortress church, separated from the rest of the congregation in a caged pew. It was Candlemas, 2 February 1779. His friend Scheidlin was next to him, the first time they had seen each other in the flesh. The circumstances of this first service spent in a cage left him with more sadness than pleasure. [Leben 2:283f]

The following day he was moved yet again. An extra battalion of troops had arrived in Hohenasperg and he was transferred to another wing of the fortress. The room was bright and cheerful with a view of human activity through the window. To his even greater delight, Scheidlin was moved at the same time into a room next to his, leading Schubart to feel that God was causing at least something to go right for him. [Leben 2:285]

He was placed in the charge of Captain Pfeiffle, a Christian of the kinder sort, a great relief from the uninterrupted hard-faced piety he had endured so far. Pfeiffle, at no little risk to himself, went far beyond his duty in helping Schubart, acting as an intermediary between him and Helene. We cannot overestimate the psychological importance of Pfeiffle's 'mail service' for Schubart – it was arguably the best thing that happened to Schubart until his tormentor Rieger died on 15 May 1782, to be replaced by a humane commander.

As always, these short moments of joy were followed by longer periods of misery. Lent that year, the season of fasting and penitence which began in the middle of February, was a hard time for Schubart. Rieger, in one of his black moods, told him he had been watching his comportment in church and that he had appeared insufficiently devout and earnest during services. Schubart tells us that he took these remarks to heart and spent the forty days of Lent in bitter self-examination. He was also plagued by toothache and pains in his chest, for the Pietist a physical manifestation of his spiritual deficits.

Easter fell on 4 April in 1779 and brought some much needed relief: he received a tender letter from Helene and he was allowed to play the organ in church. [Leben 2:298] It was an eventful day for Schubart, for on that day, after two years and three months of imprisonment, 800 days by his reckoning, he had his first walk in the open air.

Rieger invited him to walk with him around the wide promenade on the top of the wall of the fortress, from where there is a particularly fine view of the surrounding countryside, a broad sweep, a 'seven-hour valley' as Schubart described it, with 'fields, meadows, rivers, sloping vineyards, gardens, towns, villages and castles'. [Leben 2:298f]

Strengthened in body and soul I returned to my chamber of suffering and thanked God for the wonders of that day.

Leben 2:300.

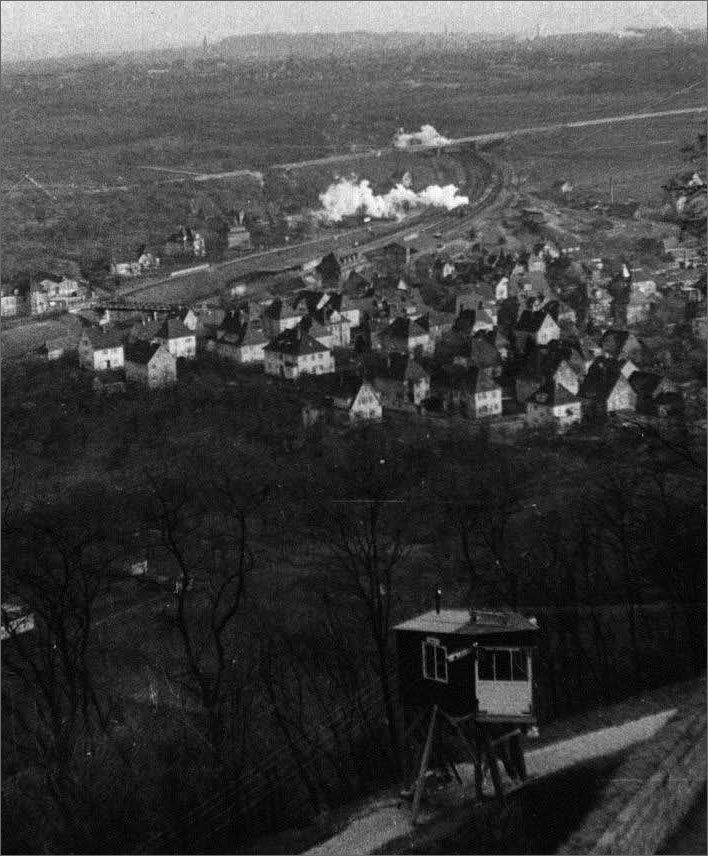

Asperg and its surroundings – Not much left of the 'seven-hour valley' for the modern visitor.

Top: A romantic evening scene looking out over the Autobahnen, factories and commercial areas around Asperg from the wall by the restaurant Schubart-Stube.

Middle: The modern town of Asperg by day, a meeting point of Autobahnen and rail. There's an IKEA store somewhere around here, too, if you need some stuff for your dungeon.

Bottom: Asperg as the US army saw it at the end of the Second World War, before the Wirtschaftswunder did its magic. The lower part of the photo shows one of the guard towers installed by the US Army to keep the interned and the former concentration camp guards safe and sound.

Rieger, the 'beast', as Schubart would later call him, even at this moment of joy for his prisoner was in fact playing with him as a cat would with a mouse. A lady who witnessed the moment that Schubart emerged into the fresh air relayed the following account:

Schubart slowly crossed the threshold of his prison. He became aware of a piano that had been set up for him on the wall (the weather was very good that day). As soon as he saw it he threw himself upon it like a tiger on its prey. He hammered on the keys like a madman for a while before noticing some ladies who were watching. He paid his compliments to them very politely, then returned immediately to the piano that he had missed so long.

Briefe 1:240f.

This anecdote is credible – quite in character for both Schubart and Rieger, who had clearly set up the situation with piano and spectators: nothing like that could have happened in Hohenasperg without Rieger's permission. No one simply left pianos kicking around on the top of the fortress walls. The presence of spectators would ensure that Schubart's eccentric behaviour would be retold in many a salon and at many a table. Not only that, but Rieger, the pious zealot, had clearly and publicly demonstrated how weak Schubart's control over his urges really was and how superficial his spiritual reform. When confronted by the object of his desires, his worldly trifles, women and song, how did he resist?

Reawakening the possibility of pleasure

After more than two years of Pietist brainwashing, Schubart now found it difficult to come to terms with these forgotten pleasures. He was able to venture out a few times more, speak to people and to play the piano to great applause, despite technical weaknesses arising from the long abstinence. When he returned to his room he was filled with guilt and unease at such vain pastimes.

He began to appreciate quiet pleasures that helped to drive his boredom away, meditating on the chatter of the swallows under the eaves of the roof, the clucking of the hen and her chicks under his window, the spider weaving a web across the grille, the sweet perfume of the lime tree, Scheidlin's tobacco smoke drifting out through the iron grille of his window as though taking the cares of his nineteen years in Hohenasperg with it.

In doing so he began to come to terms with the permissibility of pleasure in everyday life and the validity of joy experienced outside a religious context. He purges himself of the Pietist indoctrination he has suffered– perhaps it never really sat deep in him at all:

— A suitor follows a girl round the corner — so, are there sinners that the chain has not tamed? — A poor schoolmaster sends me refreshments. He looks up to me from the lane beneath, nodding sympathy and comfort. I am in tears, moved not by the size of the deed but by the love with which these things are given. — Under the lime tree a piper plays a German dance and everything becomes pantomime. The child hops around in the arms of its mother, just like a puppet. As though on strings pulled by the three-eight time he jumps right and left; the mother takes him in her arms and whirls him around. How can dance be so reprehensible when it is so much in our nature? Not at all — dancing, too, has its time.

Leben 2:314f.

He ends his autobiography on 'the 819th day of my captivity, 21 April, 1779' [Leben 2:320] at a moment of closure, lifted up by the possibility of a spiritual reconciliation beyond the narrow confines of Pietist theology, indeed, for which he quotes biblical authority: 'In my Father's house there are many mansions'. [Bible John 14:2. Leben 2:317]

In the the last paragraphs of his autobiography Schubart the German patriot speaks, one of the few constants in his character:

O Fatherland, God knows, I have loved you! Not all of your free, noble, modest souls are dead; but they groan in the chains of despotism; they wail at the ruination of their children; they sit like Elijah under the juniper bush [Bible 1 Kings 19:4 (KJV)] and say: 'It is enough! So take my soul to you, Lord!' – May God help you, when you can be helped.

When I am gathered to my people – for even after death and in the coming eternity I hope to be your comrade, my German brothers, because the nations will stay together – I want to plead for the triumph of you and your brothers, for all the innumerable joys that have been given to me with your language, your customs, your great minds, your wise and pious men, your gentle and simple feminine souls, your children, your food, your refreshing drinks, your beautiful scenery: your mountains, your valleys, your rivers, your air, your moderate skies, your towns, your villages, your buildings, your gardens – – accept the thousand thanks of my tears!…

And now – and just a few shovels of soil from you on my grave mound: then farewell for ever!!

Leben 2:319f

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!