Schubart's dungeon cell

Richard Law, UTC 2017-05-15 18:41

In the dungeon

His cell was a mouldering, damp hole at the base of a stone tower, closed with an iron door. In the corner was a bed of straw. The window was a square hole little bigger than the width of a hand. It had bars over it and was located high up in the wall – too high for the prisoner to look out. Through the window neither sun nor moon ever shone directly. On fine days there was merely the 'quiet sunlight that hung on the iron bars of the grid'. [Leben 2:190]

There was a small iron stove. The barrel roof of the cell was black with age and soot. An iron ring was fixed into the wall so that he could be chained were he to show the slightest disobedience. The air in the cell was cold, dank and still.

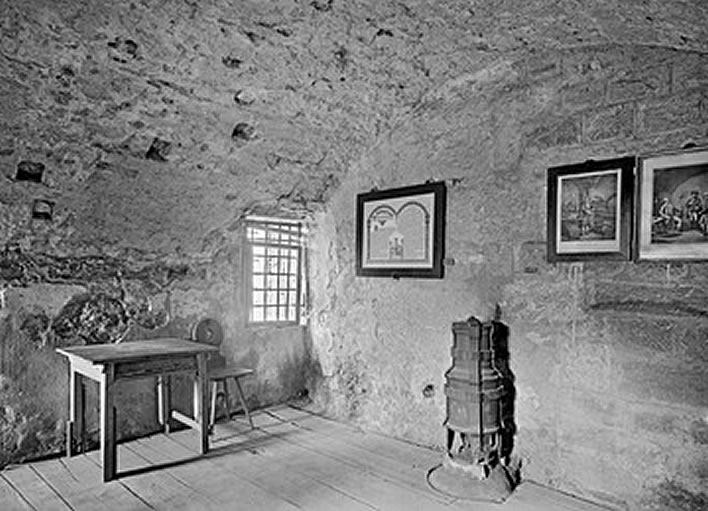

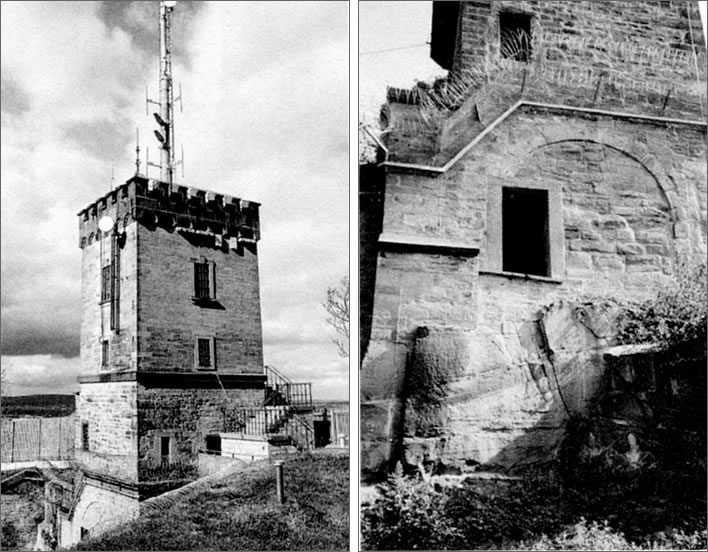

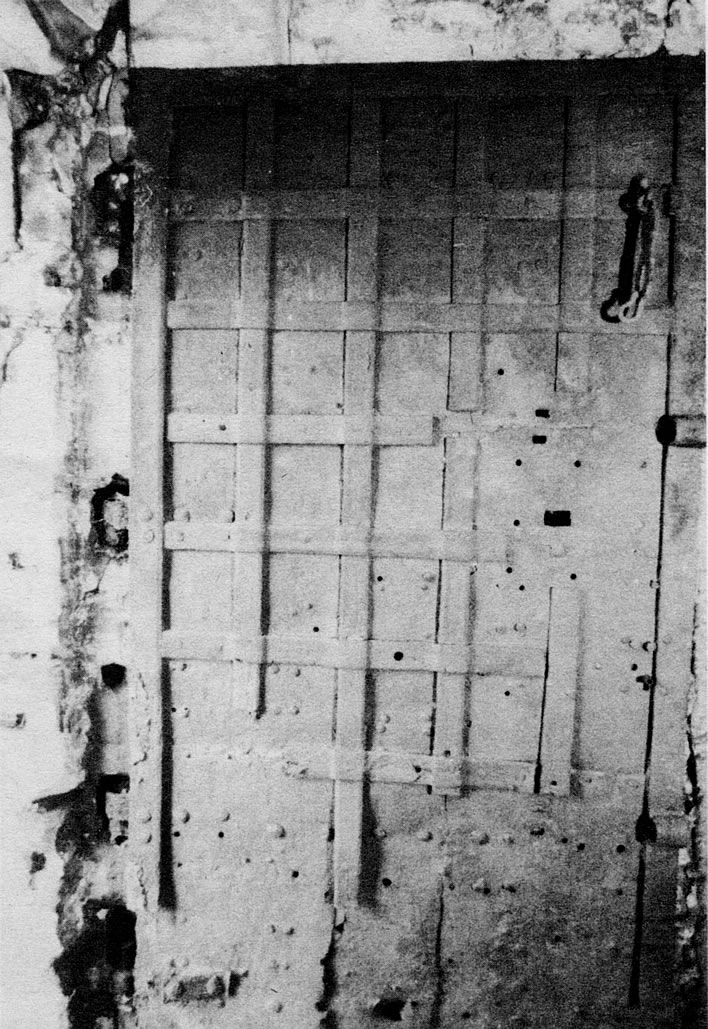

In 2010 a Hohenasperg Museum [€-kerching!] was opened, located in the Arsenal building. This meant that visitors to Hohenasperg no longer had to be shown the completely fake 'Schubart Cell' in the 'Schubart Tower'. Top: A relatively modern photograph of the fake cell. Image: [Ranke 5]. Bottom: The same fake Gefängniszelle von Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart in a photo from 1936. Image: ©Landesmedienzentrum Baden-Württemberg, 1936.

The fake Schubart cell was accessible from the promenade along the top of the fortress wall and was thus a convenient lie for the walkers and tourists who found their way up to the fortress. What is now thought to be the real Schubart cell is on the floor beneath, its entrance on the courtyard side, within the secure area of the prison. On the modern aerial view on the previous page you will note the amount of security fencing now sealing off the inside of 'Schubart's Tower' from the freedom of the world outside.

A photograph of the inside of what was probably Schubart's cell. As a result of building work in the prison, the cell has been inaccessible since the mid-1950s. Image: [Müller 13, photo G. Brumm, Hohenasperg].

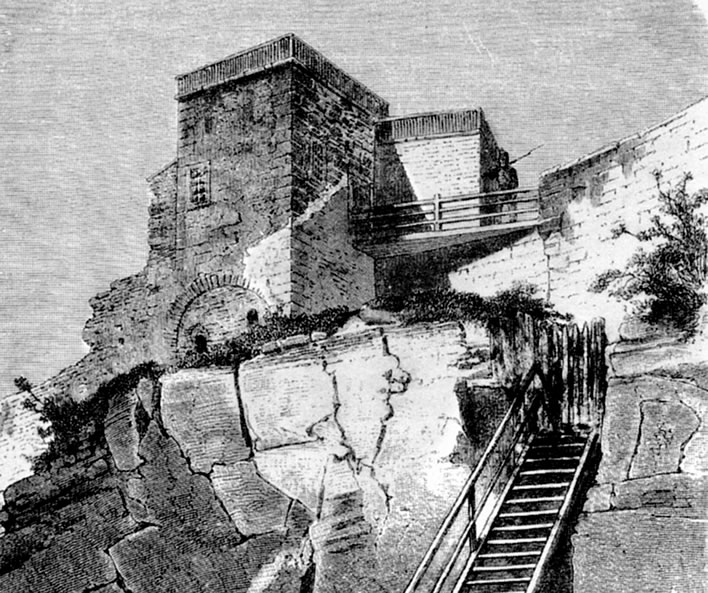

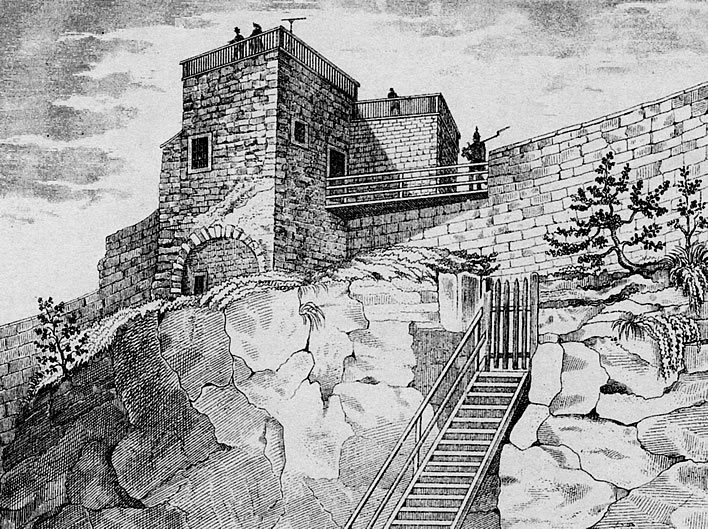

Two drawings of the 'Schubart Tower' from inside the fortress, a place now no longer accessible to the sane. Both drawings date from around 1860 and appear to be derivative. The entrance to Schubart's cell is the small door under the left of the arch at the base of the tower. The access route was removed during building work in the 1950s. Top: [Ranke 4]. Bottom: [Müller 14].

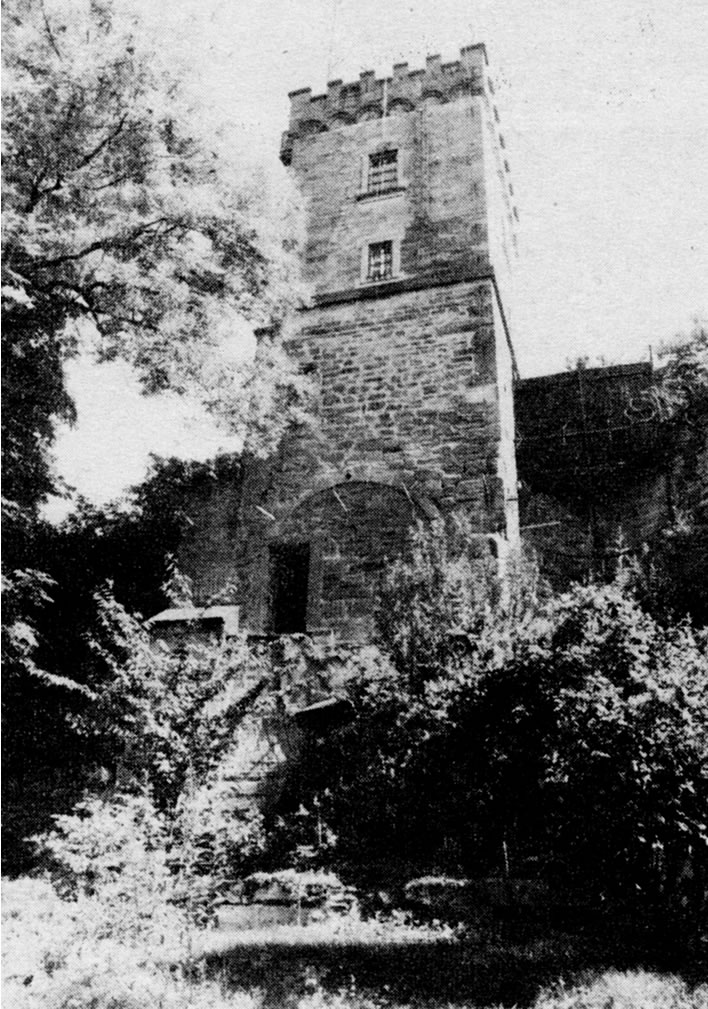

A photograph of the 'Schubart Tower' from inside the fortress taken in relatively modern times. The door to Schubart's cell is open. His 'window' is not visible on this photo: it is on the left-hand face of the tower in the angle where the tower meets the fortress wall. It faces north-east. The structure on top of the tower is a water tank that was built in 1886/87. Image: [Müller 14, photo: G. Brumm, Hohenasperg].

Two photos of the 'Schubart Tower' in modern times. Left: The door to Schubart's cell is bottom left, unter the arch. Right: The entrance to Schubart's cell is around six metres above ground – bring your own ladder, or perhaps better not… [Ranke 6].

The door to Schubart's cell. Top: in situ. Image: [Müller 13, photo: G. Brumm, Hohenasperg].

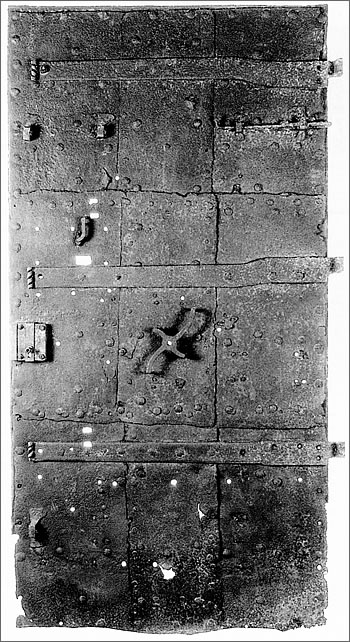

Bottom: Now 'museumized' in the Hohenasperg Museum [€-kerching!]. Nothing museum curators do shocks anymore: in this case the paying public are shown the face of the door seen by Schubart's jailers. Schubart's less scenic view of the door would be this:

Schubart's view of the door in his dungeon cell. We can be sure that in his boredom he counted every bolt and rivet.

From the moment he was put in his cell no one was allowed to speak a word to him, not even those who brought him his food and water. He was allowed no books, no piano, no paper or pen. He could have no visits, see no family, could not read or write letters. [Leben 2:147] He would hear occasionally voices from outside and would pass the time imagining the appearance and character of the speakers.

We moderns need some moments of reflection in order to comprehend Schubart's state in his cell. Almost every second of our busy lives is filled with some distraction or stimulus. We fill the vacuums of our existence with talking, reading, texting, surfing and all the possibilities social media offers. Nowadays we would say that Schubart's state in that dungeon was close to being sensory deprivation.

The calendar used by the rest of the world, with its months and weeks and days of the week became meaningless to him. He counted days. He would count 377 days creep by in that cell. He counted hours and heard 'the tread of minutes passing', as he put it, so sensitive in his boredom his ear for time became. [Leben 2:150] He even counted his pulse.

He would sit for hours on his straw bed watching the spiders spin their webs, catch and devour their prey; listening to the flies buzzing; watching in the night the glowing firefly climbing his wall. He killed no creature that came into his cell. [Leben 2:190f]

His mind was suddenly suspended in isolation. A mind that up to then had fizzed with ideas and projects, one after the other in quick succession, ricocheting off the last thing read or heard – too many ideas, too quickly, in fact, for his own good. Time was a precious commodity for artists and thinkers: lives were shorter and could be ended unexpectedly and abruptly by disease or accident. For Schubart, 38 years old and at the height of his powers, each day lost, never to be retrieved, was a small tragedy.

The worst thing must have been the uncertainty of his future. No judicial process had brought him there. There was no fixed sentence to be served: he could be there for another week, month, year or the rest of his life. Unlike the judicial prisoner he could not tick off days served; unlike the boarding school child he could not tear off paper strips for the days left before the holidays began. His future simply opened up into a featureless void.

The permanent present

The ban on writing was a particular torture for him. He was a compulsive scribbler now forced to live in the dreamtime present in which humanity existed before the invention of writing. No thoughts or ideas could ever be memorialised – they just drifted into the oblivion of the past.

Schubart was an oral creator. In his Ludwigsburg days, his son Ludwig tells us, he would go for walks and create in his head 'poems, letters and other essays which he would write down later'. The last issue of the Chronik before his capture was 'dictated in the middle of the night, without the need of a single printed source' [Karakter 6]. But ultimately all these oral creations had to be written down – and that, in his dungeon, he could not do.

In the Chronik in 1775, 1776 and then again in 1789 and 1790 you don't need to search long to find pieces that he had dictated in one-and-a-half, maximum two hours, with a strong voice, and on occasions so quickly that the scribe could scarcely take a breath […] Even poems he dictated like this, while conversing with someone or looking out of the window at the world passing by.

Karakter 23.

Now in solitary confinement in his cell he began to write drafts of books and poems in his mind, but he needed writing, not memory. He first tried scratching his compositions down using the sooty point of the candle trimmer, with some success: he accumulated a small collection of works, which he kept hidden underneath a board in his cell. [Leben 2:191f]

Unfortunately, he was just in the middle of scratching down a verse when the commander of the fortress, Colonel Rieger, visited him unexpectedly and caught him trying to secrete the paper. Rieger forced an admission of guilt out of Schubart as well as the whereabouts of his cache, all of which he confiscated. Rieger threatened to have him strung up to the ring in the wall if he tried again to write. The points of the trimmer were filed down and his efforts confiscated and lost for ever, a matter of lasting regret for Schubart, who felt that the lost pieces would have been counted as being among his best work. [Leben 2:192]

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, unknown artist, date post 1784. The stone block has the text engraved: SCHUBART / IN FESSELN FREI, 'Schubart / free in chains'. Image: ©Tobias-Bild Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen.

Despite his fear of punishment, so strong was the urge to write that he tried again, this time managing to scratch a few pieces using the prong of the buckle of his knee breeches. Again he was discovered and his work confiscated. A while later he managed to secrete a fork to scratch with, but this was also discovered and taken from him. [Leben 2:193]

We noted the same compulsive need to write in the case of Andreas Riedel, who was imprisoned in the fortress of Munkács in Hungary for his complicity in the 'Jacobin Conspiracy' of the 1790s. Riedel scratched a 3,000-line poem using the soot from his stove on his dungeon walls, which was then painted over when the authorities found out. It seems to be existiential for long-term or indefinite prisoners to memorialise something from the featureless, wasted, permanent present that drifts past them.

In some respects Schubart might consider himself lucky to be in Hohenasperg: before Duke Carl Eugen got to him, the Austrian ambassador had offered to make Schubart disappear in one of the fearsome fortress prisons such as Munkács in the east of the empire. [Leben 2:131]

Sanity, the prisoner's friend

Unsurprisingly, in this isolation Schubart slipped into a deep depression. He was by nature a wildly convivial extrovert: a renowned musical virtuoso and music teacher – a man who loved to perform; a writer, poet, chronicler and commentator; a titanic drinker and eater; a committed womaniser, whose spiritual home was the tavern.

As his son Ludwig later wrote, he had been abruptly removed from the Dionysian turmoil of his life:

Just think of this man, removed from the whirl of a dithyrambic life into a deathly loneliness, where he has nothing but the rubble of his past before him.

Leben 2:ix.

He slept badly and suffered frightening hallucinations by day and night. He had been a masterful drinker but was now suddenly sober. Those who knew him and his wild, erratic character gave easy credence to the rumours that he had gone mad and was now strapped down on a bunk or hanging from a chain, raving. Rieger went so far as to explicitly deny the substance of these rumours to a correspondent:

Do not in the least believe the rumours of indisposition or madness. They are completely without foundation. I expect Schubart's future account of this time to show that he was never refused even the smallest thing that he could ask of me.

Briefe 1:265.

There is, however, despite Rieger's dissembling account, no doubt that Schubart came to the edge of insanity, but, despite all the deprivations he suffered, he never went beyond.

By the end of the first, terrible, year Rieger seemed to have broken him, physically and mentally.

My memory had shrunk so much, my imagination was so brittle and dark, my heart so pressed and exhausted, my mind so timid and my horizon so damp and narrow that I no longer recognized myself and wept bitter tears over the decline in my mental powers. … How true, how unbelievably true is the interdependence of soul and body! … I shall never recover my previous zest and the harmony of my mental powers, and this is the saddest side of my fate.

Rieger and Zilling not only wrecked his mind and his body, they also tried to wreck his self-esteem, doing their best to purge all that was so characteristically Schubart out of him. By the end of that first year the proud, defiant troublemaker, the Bacchanalian, the man full of vitality and full of the love of life and been reduced to a whimpering regurgitator of prayer, who viewed himself now not just as a disorderly man, an unfaithful husband and a neglectful father but worse, as an enemy of God, a fallen comrade of Satan, for whom no hell was deep enough.

The opera singer

Other, earlier inmates of Hohenasperg had been less resilient, the most notable being Anna Maria Pyrker, a famed opera singer at the court of Carl Eugen. In 1756 she foolishly told her friend the Duchess about the Duke's affair with a dancer.

Carl Eugen was a notorious womaniser, mentioned admiringly for his prodigious consumption of attractive young women by the great Casanova himself, who visited the court in Stuttgart in 1760. The Duke produced one daughter by the Duchess and well over a hundred other children by a long series of women. His dalliances continued almost onto his deathbed. His particular preference was for dancers and singers.

All his dancers were pretty and each was proud to have made their lord happy at least once.

Casanova 4:8:250

But no young woman was safe from him. He would take advantage of the audiences he held with his subjects to find new conquests. As Casanova put it:

He examined the complaints of the pretty country girls in private. Although he usually disallowed their requests, the girls went away comforted.

Casanova 4:8:252

There was nothing particularly scandalous in this behaviour, which was almost expected of the autocratic rulers of the time and even legally regulated with a financial settlement. The girls' families were happy to receive the money and the blessing of a blue-blooded child, who would receive favours and advancements from the Duke. People would look at young men and remark on the likeness of the Duke in their faces.

A still from the film Friedrich Schiller – Der Triumph eines Genies from 1940, directed by Herbert Maisch. Here we see Franziska von Hohenheim (Lil Dagover) cheering up hubby Carl Eugen (Heinrich George). The National Socialists of the Third Reich despised the aristocracy as much as all the other socialists of the time, so the villain of the film, Duke Carl Eugen, is presented as a pompous, rotund, overfed slob with more than a passing resemblance to Hermann Goering (which may have been Dr Goebbels' intention). The Nazis were desperate to find German heroes to inspire their public and Schiller for a time fitted the bill as a German 'genius'. There was even a brief dalliance with Schiller's play Wilhelm Tell, which came to a rapid end when the upper echelons of the party realised that it was all about overthrowing tyrants.

As a contrast, here is a view of Franziska and Carl Eugen from 1787, done by one of the pupil's of the Carlsschule– the same school ('the slave nursery') to which Schubart's son Ludwig was sent. The style is too artless to be a cosmetically improved representation of Carl Eugen.

Thus when the Duchess heard her friend Anna Maria Pyrker's gossip she can hardly have been shocked by the Duke's infidelity, but the Duke was angered by Pyrker's disloyalty towards him. Despite the pleas of the Duchess, Carl Eugen imprisoned Anna Maria in Stuttgart.

Imprisoning her friend in spite of her intervention on Anna Maria's behalf was an insult that the Duchess could not tolerate, particularly since the original fault had been his. For the Duchess, the comedy had to end. She left Carl Eugen and went back to her native Bavaria, never to return. In doing so she made matters much worse for her friend.

Now even more enraged at the trouble Anna Maria's loose tongue had caused him, the Duke sent her to a dungeon in Hohenasperg, where she was held completely alone for eight and a half years. Like Schubart 20 years later, she was imprisoned without any judicial process and for an indeterminate period. It is said that her voice broke with her screaming. In time her mind broke, too.

In her lucid moments she would make flowers out of straw from her bed, tied with her own hair. Taking pity on her, the Commander of the fortress let her have thread and wire for this diversion. Her skills improved until she was making entire bouquets of flowers with great artistry. One of these bouquets reached the Empress Maria Theresia in Vienna, another the Empress Catharine II of Russia. These two great women of Europe interceded with the Duke on behalf of Anna Maria, who was finally released in 1765 after nine years of solitary captivity. Over time her mind recovered, but her beautiful soprano voice was gone for ever.

Her story was familiar to Schubart, who had met her in June 1773, eight years after her release. He noted that although her voice was wrecked as far as performance was concerned, far from being just a 'stuffed nightingale' she had become a useful singing teacher.

He could not know that in a little more than three years after that meeting he, too, would be trying to stay sane in solitary confinement on Hohenasperg. Her fate must have crossed his mind when he found himself being driven up the wintry road to the same fortress that had driven her mad, and would have haunted his thoughts during his own long years of isolation.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!