Free at last

Richard Law, UTC 2017-05-15 18:50

Schubart was released from Hohenasperg on 11 May 1787, 230 years ago this month. It had taken him ten years and five months from his ascent to the fortress to descend the 'highest mountain in Germany'. His release was even more casual and free of formality than his capture had been. In one account the Duke and the Duchess appeared on Hohenasperg on 11 May and announced that he was free. Tellingly, for those who see Franziska as the motor behind the Schubart's imprisonment, it was she who made the announcement to him. [Hauff 225]

In another account, however, Carl Eugen announced Schubart's freedom to him directly. At a parade on the Hohenasperg at which Franziska was almost certainly present the Duke suddenly turned to Schubart and said 'Schubart, he is free'. [Hauff 226]

The Prussian connection

Finally, just as it had been in the case of Anna Maria Pyrker, it was the intervention of two great names that effected Schubart's release.

Another poem, which [like 'Fürstengruft'] had a big effect on his life, was a hymn to Friedrich ['the Great'], which he wrote for the second volume of his poems – also a poem that had matured in his mind over a number of years and which he brought to paper in a few hours. One can say literally that he sang his freedom with this hymn. Immediately after Friedrich's death [17 August 1786] the book dealers Himburg, and Deker in Berlin printed and sold it in its thousands.

It had such an effect on all classes that everyone asked enthusiastically who the author was. [Ewald Friedrich von] Her(t)zberg [Prussian Foreign Minister, (1725-1795)] and the current Duchess of York [Friederike von Preußen, (1767-1820), the daughter of Friedrich's successor, the disastrous, grotesque, Friedrich Wilhelm II.] were moved to turn to the Duke [of Württemberg] in order to effect his release.

This took place soon after, with the statement that: 'A wish of the King's is as much as a command for the Duke'. Friedrich's admirers knew the poem by heart.

Karakter 41.

Schubart had been a lifelong fan of Friedrich the Great and Prussia. During his dangerous time in Ulm, the Prussian soldiers whom he had befriended had even been useful bodyguards. [Leben 2:133] It is thus fitting that it was Prussians who got him out of Hohenasperg. And – this is Schubart, after all – predestined that they would come to regret it.

Schubart had been captured two months short of his 38th birthday and had spent ten years and almost four months in the fortress of Hohenasperg. When he was released he was 48 years old. His middle age (in 18th-century terms) had been spent in prison.

On his release he was given an amiable audience with the Duke. Neither then nor any time later did Schubart display any resentment against the man who had had him locked up in a fortress during ten of a man's best years. This character 'weakness', this lack of perspective and continuity, this permanent present in which Schubart seemed to live was now a great advantage for him: it meant that his last years could be passed at peace with his Duke and not wasted in lingering resentment and enraged dreams.

Return to Stuttgart

He was appointed 'Director of German Theatre and Music' to the court in Stuttgart. He became the court poet, required to churn out encomia on birthdays and name-days of the man he had called a 'Satan'. He seems to have done this with enjoyment, at least for a time.

Carl Eugen, the man who had robbed him of those ten years on a whim, also appears to have undergone an amazing transformation. He was now employing Schubart, albeit for only a modest income of 600 florins, even more modest when we consider that he was no longer paying Helene her 200 florins and Ludwig was now finished at the Carlsschule.

Financially, the arrangement made sense from Carl Eugen's permanently cash-strapped perspective. In the fortress this troublesome gnat had just been costing him money. He had been paying for Schubart's increasingly sumptious keep on Hohenasperg, paying his wife a pension and supporting his son in the Carlsschule and his daughter's education. When the Prussians gave him an excuse to show gracious mercy to Schubart, they were pushing against an unlocked door.

Schubart described his exit from Hohenasperg and his entry into Stuttgart in a letter to his son, who at that time was in Berlin. We are told that on his departure from the fortress there was barely a dry eye among the officers and the troops and the other prisoners. Arriving in Stuttgart, we are given the impression that there was dancing in the streets. The following day he was shown the church and the theatre, and a short while later went with Helene and his daughter on a journey to Geislingen, Ulm and Aalen. More dancing in the streets and popular ecstasy!

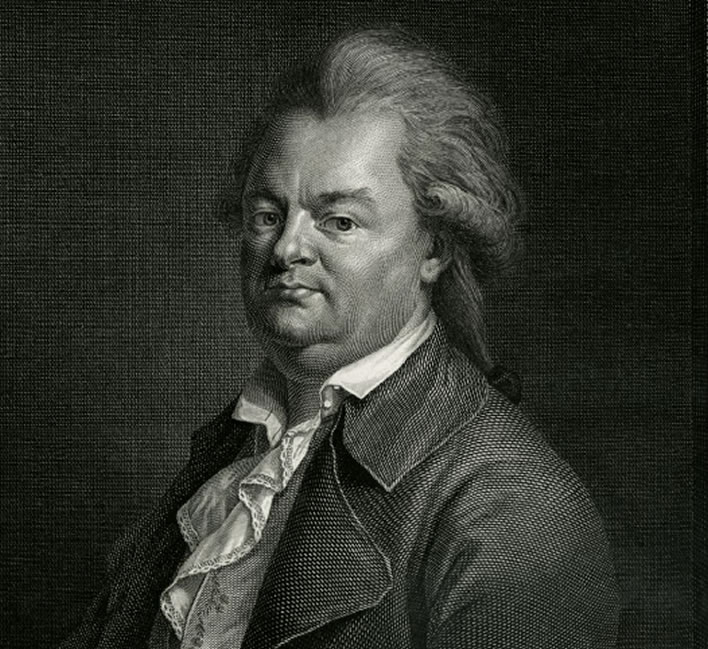

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart in an engraving by Ernst Morace (1766-18??) from a painting by August Friedrich Oelenhainz (1745-1804), 1791.

The following notice of this engraving was printed in Die fortgesetzte Schubartsche Chronik für 1792, 'The continued Schubart Chronicle for 1792', no. 14, Friday 17 February 1792, p. 112. [Schubart had died on 10 October 1791]:

Art News

One promising artist after another is appearing from the Art Academy here in Stuttgart. One such is the Court Engraver Morace, who has engraved beautifully the long promised picture of our deceased friend Schubart, based on an excellent painting by Oelenheinz. Power, expressiveness, honesty and accuracy mark out this work of art. It seems to me that the character of the face, the fiery spirit that speaks in each line, has been achieved especially well. In short, the painter and the engraver have certainly summoned all their powers in order to give the many friends of Schubart a picture of him that is so true and so complete. This engraving can be purchased for 2 florins from the author or at any Post Office.

The journalist reawakens

But even more surprising in the looking-glass world in which we now find ourselves, Carl Eugen allowed Schubart to restart his newspaper, this time under the name of the Chronik. And no only that, he freed the publication from censorship supervision, which was quite astonishing when we recall that Schubart's unrestrained journalism ten years before had given offence to most of the 'crowned heads of Europe' – at least so it said in the order for his capture.

The great balsam that heals the deepest offence is money. Carl Eugen's court printers had made a profit of 2,000 florins on the production of the two volumes of Schubart's poems whilst their author was locked up in Hohenasperg (Schubart himself got 1,000 fl.). Now, after his release, the new Chronik was printed by them too and created another profitable income stream.

It wasn't all easy money for the Duke: in return for his his tolerance of Schubart and his Chronik the Duke had to deal with a steady flow of complaints and objections from all over Europe. In the pressure to publish against deadlines Shubart was frequently led into printing incautious tittle-tattle, on one occasion with consequences that Schubart imagined might get him back into a dungeon. Despite that, the considerable profits that flowed to the Ducal printers appear to have been sufficient to keep the permanently cash-strapped Duke on Schubart's side.

Six weeks after his release the first issue of the new Chronik appeared. It reflected all the conflicts and dissonances in its author's mind: Prussia, which Schubart had idolised under Friedrich II, was the state which, under Friedrich Wilhelm II had obtained his freedom – under the same 'fat fornicator', it was now behaving indefensibly; Joseph II of Austria was dying stoically but had left his empire in chaos; at his entry into Hohenasperg Schubart had been the great mocker of the religious establishment, on leaving he was now, presumably as a result of Zilling and Rieger's attentions, a religious bigot of the first chop who now bore a grudge against Joseph II because of his anti-religious tendencies; in 1789 the French started their revolution to overthrow the yoke of princes, that is, the likes of Schubart's benefactor Carl Eugen, simultaneously overthrowing the church in France, forcing Schubart to take quite bizarre positions on this greatest issue of the century in his Chronik.

His Chronik became a strange brew of religious obscurantism and contradictory, half-baked political opinions having not the remotest relationship to 'enlightenement' or reason. Nevertheless, it sold and brought in considerable amounts of money. Schubart, in his first year, had an income not of 600 florins, but 4,000 florins. He was now prosperous – which had always been a bad thing for Schubart to be.

The road to ruin

After leaving Hohenasperg the now 48 year-old Schubart had four years of life left. His year in a dungeon had damaged his health: the poor nutrition, the cistern water (as opposed to spring water), the cheap, acidic and possibly poisonous wine and the lack of all exercise consolidated the wreckage. Towards the end of his time there he had started drinking cheap spirits, which did even more damage.

Now, in Stuttgart, his new riches and freedom of choice were not used wisely. He ate too well and above all drank immense amounts, particularly with his drinking partner, a Falstaffian roofer called Bauer. It is said of Bauer that he would lose count of the bottles he had drunk so he kept the corks in his pocket for when the time came to pay the bill. [Hauff 239] Schubart was frequently drunk 'until his hair steamed'. Helene had at least managed to wean him off spirits.

The fatter he became the less exercise he took. When son Ludwig came to visit him in 1790 he was shocked by the appearance of his father: bloated and red-faced. Ludwig tells us that an aquaintance told him, after Schubart's death, that his father would have still been alive had he stayed in Hohenasperg. [Karakter 10]

The German poet Justinus Kerner (1786-1862) was a small child growing up in Ludwigsburg when Schubart was released from Hohenasperg. He gives us a brief glimpse of Schubart in those last years, before his decline had gone too far:

Rather clearer in my memory is a man who at that time and also later often visited our house and over whose stick my brothers fought in order to ride on it. He was a powerful figure with big eyes, a turned-up nose and a toupee-like haircut, a man with lively movements and a powerful voice: the poet Schubart.

He was released from his ten-year imprisonment in the year of my birth and named as Court Dramatist in Stuttgart. He often visited Ludwigsburg, his residence in earlier years, as well as my father, when the court and the theatre personnel were there.

My father liked him for his talents but was often required, as a civil servant, to intervene because of his excentric, indeed immoral nature. Despite that, Schubart expressed his gratitude to him in his autobiography. He said of my father: 'Government minister Kerner, the best, the worthiest soul, loves and values me despite all my errors, in the humane expectation that the storm will subside'. He was godfather to Schubart's son, who was born in Ludwigsburg.

Schubart usually came in the evening to us, around my bedtime. He soon sat down at the piano, played and sang. I rarely fell asleep, but out of fear pretended to be asleep.

Kerner 6f.

Schubart suffered depression that gradually became permanent and manifested in an apathy that let everything slide except the Chronik– his music and theatre duties suffered in particular: he stopped turning up altogether after a time. He would knock off an encomium for the court when required but in his black depression let the administration of his own life founder. Helene, the long-suffering wife, described the situation in a letter to their son Ludwig in August 1790:

… Your father is now so inactive that it is often difficult for him to sign his own name. From this inactivity there arise a thousand problems, since his lively spirit still has to be occupied. He still delivers his 'Chronik' – in order to live – and this costs him two half-days a week. But that is everything he does; he has completely abandoned his official job. Only following pleading and threats does he write the prologues for the Duke's birthdays and name-days, but otherwise he has not been in the opera house for a whole year.

He does not answer the most important letters, to his great disadvantage. He also promises this or that person a lot, but does not keep his promises. He is either suffering from hypochondria and imagining that he is ill, or he wants to play the great man and indulges in pleasures that gobble up money, often with unsuitable people. Whenever a lad turns up who is good at emptying glasses, he is his man. Most of this comes from his upbringing and from Aschberg [recte Asperg].

Strauss 285f.

In the autumn of 1791 he developed Schleimfieber, typhoid fever. Death came to him gently between eight and nine o'clock on the morning of 10 October 1791.

Helene, Ludwig and Julie

He left his wife destitute. Helene told their old friend Miller in March 1792 that Schubart had paid enough money into an insurance to provide her with 200 florins a year for the rest of her life – unfortunately he died many weeks to early to meet the conditions of the policy, meaning that she wouldn't get a penny. On another occasion he had told her that Carl Eugen should provide a pension for her, but that was obvious wishful thinking and he himself doesn't seem to have intervened to secure one. [Briefe 2:802] Ludwig, for whatever reason, could or did not help her financially.

She would outlive her husband, their son Ludwig (d. 1811, age 45) and their daughter Julie (d. 1801, age 33). Helene lived another 25 years after her husband's death in bitter poverty, dying in Stuttgart on 25 January 1819, aged 76.

The god of biographers likes us to find a hero somewhere in every tale. Captain Pfeiffle in Hohenasperg is a good candidate, but the real hero has to be the heroine Helene Schubart née Bühler. Her husband had brought her many dark moments: the beatings, infidelities, gonorrhoea and illness in Geislingen and Ludwigsburg; the year when he abandoned her and his family on a whim without a word whilst he wandered from one scrape to another around Germany; the ten years of her husband's absence on Hohenasperg when she had to cope alone, piously thinking only of his welfare; then four years of his drunken decline and predestined end.

At least in those last years he stopped beating her, finally realising how dear a family life was to him. All this she bore with a pious and touching simplicity of spirit. Hauff [255] points out the educated German and commendably plain style of her letters, 'free of all bombast and pomp' – perhaps she should have written Schubart's poetry for him.

In the final 25 years when she was completely alone and desperately poor, even Miller, the moral support for the Schubarts during the Hohenasperg years, stopped writing to her shortly after her husband died. We have one letter from her to him in 1811, pleading for his help to obtain a stipendium for someone else. For herself she asks for nothing.

Literary and musical stuff

Apart from Die Forelle and Die Fürstengruft Schubart's poetry is forgotten. His work was dated and mannered even when he wrote it; now, it is ridiculous and unreadable. The works which were scribbled down on Hohenasperg and then smuggled out not without risk are just inconsequential rococo nothings, full of shepherds and shepherdesses and more shepherds and May mornings and red skies and more shepherds and maidens and babbling brooks and so on and so forth.

These works are reminiscent of the bucolic fakery that the French queen, Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), was pursuing almost simultaneously in her mini-palace Le Petit Trianon, where in the years after 1774 she created an entire rustic village of millers, shepherds and miscellaneous yokels for her entertainment. Schubart, despite his grumbling about his betters in Die Fürstengruft simply did not have the talent or the imagination to go beyond the worn-out imagery of the rococo mind.

One really expects better of imprisoned writers who have had so much time on their hands to think about their work. Put harshly, we see that Schubart was not in the least a creative artist but a mimic: he produced work in the manner of his predecessors. His biographers, duty bound to form an opinion on his work, take a dutiful number of pages to reach our conclusion. [Briefe 2:305-321], [Hauff 2:260-308].

The same applies to his music. The evidence? Not a single piece of his music is performed. Ernst Holzer, in Schubart als Musiker, his admirable Teutonic sense of duty gnawing at his conscience, apologised to his readers for not expending the effort to track all the minute changes between versions – even of Die Forelle. Such minutious labours are 'only appropriate in the work of a great artist'. [Holzer 115] In mitigation, however, he points out that Schubart's ten years on Hohenasperg coincided with the glory period of Mozart and wonders how much Schubart's music might have improved had he been exposed to that master. [Holzer 25]

Finale

In Schubart we have a flawed hero: a drunk, a wife-beater, a show off, a troublemaker, a philanderer. He was irrational, incautious, loud-mouthed, intemperate and inconstant. Oh, and a generally terrible poet. He was, however, arguably the first political journalist; whether he was brave or simply foolhardy? – probably a bit of both. He was not a Jacobin revolutionary: he admired Friedrich the Great and was always a steadfast fan of Prussia. He hated hypocrisy, particularly in the clergy, whether Catholic or Protestant. He respected the common people of Germany and could never resist mocking the Bourbon affectations of the great and the good. He himself could not understand or speak French or English. [Karakter 95n.]

If Carl Eugen had not let himself be provoked into trapping and detaining Schubart we would probably know nothing about the troublemaker today, at most he would be a footnote, his Deutsche Chronik offering interesting browsing for historians of the period. Carl Eugen would have had one sin fewer to add to his list and his ducal throne would have been just as safe. For us Carl Eugen would have been just one more extravagant despot in a large field.

On the other hand, if Carl Eugen had not got to him first, the Austrians might have carried out their threat to cause him to vanish into a fortress in Hungary, which would have meant the rest of his life chained in a dungeon, not just one year. Or the monkish priests might have caught him on their territory and beheaded and/or burnt him at the stake, just as they had done with his young friend Josef Nickel six months before Carl Eugen struck. Franz Schubert would never have composed one of his most loved songs,Die Forelle, nor his much-loved Forellenquintett. Schubart survived it all, so now, 240 years after he was escorted to his dungeon and 230 years after he was escorted out, let's give thanks to Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart for a wild life, wildly lived.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!