The commander and the clergyman

Richard Law, UTC 2017-05-15 18:42

The commander

The only person allowed to speak to Schubart was the fortress commander, Colonel Philipp Friedrich Rieger (1722-1782). His task was to show Schubart the error of his ways and to bring him onto the path of righteousness. Rieger told him that he had suffered a shipwreck and that now only one plank remained to hold on to: religion. [Leben 2:157]

Schubart was to be 're-educated' and Rieger was just the right man for this task. During his time persecuting Schubart, he was promoted to the rank of major general.

Philipp Friedrich Rieger, artist unknown, date unknown. Image: Stadtarchiv Asperg [Ranke 14].

Rieger's monument in the Michaelskirche in Asperg. Schubart wrote the inscription, which pulls out every stop on the organ of baroque pomposity. Image: Chris Korner [Ranke 15].

Rieger, as Schubart himself put it, had 'experienced the sweet and the bitter in life'. His talent for organization, his military skills and single-mindedness had helped Duke Carl Eugen out of a number of serious difficulties, all of them of the Duke's own making. As his usefulness grew Rieger rose rapidly to occupy one of the highest positions in the land.

He had entered the service of the Duke in 1756, at the start of the Seven Years War. Carl Eugen, ever short of money, had sold the French an army of 6,000 men for 600,000 florins, even though he only had 2,000 men available. When the French requested the troops for which they had paid, Rieger it was who went round the country pressing into service any likely man over 18. Half of this army deserted from the barracks before it had even set off. Most of the deserters were rounded up, but then a third of the army deserted again when they reached the theatre of war in Silesia.

Forcibly conscripting the sons of farming families and any other young men who didn't have a good excuse required a heartless, single-minded brutality. The fact of Rieger's success tells us that he had this. Alongside famine and disease, conscription into the great land armies to fight the bloody dynastic battles of the 18th-century was one of the principal causes of social misery and unrest of the time. Schubart had sharply attacked the practice of drafting young Swabian men to fight in foreign armies on several occasions in his Deutsche Chronik.

Embarrassingly, in his desperation for money to finance his extravagances, Carl Eugen had sold a portion of the young male population of his country to the French, who then used them to attack his friend, ally and protector Frederick of Prussia, who had raised him for two years after the death of his father.

Rieger had to repeat the operation the following year, this time even managing to produce an army of 12,000 men to fulfil yet another wild commitment of Carl Eugen's to the French. Rieger's thoroughness, ruthlessness and brutality in accomplishing his task made him a household name. Within a few years he rose to be the indispensable servant of the Duke, doing whatever his master required of him.

His fall from grace in 1762, only six years after he had entered the Duke's service, was rapid and brutal. Rieger's arch rival at court, Count Montmartin, showed the Duke a faked letter implying that Rieger was negotiating with the Prussians.

The Duke, always paranoid about conspiracies among his servants, by his own hand publicly stripped Rieger of his rank and office. Rieger was briefly imprisoned on Hohenasperg, then sent to the fortress of Hohentwiel, where he spent the first part of his three and a half year incarceration in terrible, squalid conditions, lying in his own excrement. Reading the only book allowed him, the Bible, bore him through these terrible times and left him with a deep, utterly unswerving, ruthless and self-righteous piety.

His time in Hohentwiel did nothing to change his brutal and despotic nature: Rieger went into Hohentwiel and Rieger came out again, just with another unpleasant layer of zealotry added to him. In 1775, eight years after Rieger's release from Hohentwiel, Carl Eugen reinstated him to his rank and his station and in 1776, the year before Schubart arrived, gave him command of the fortress of Hohenasperg. The prisoner was now the jailer.

The original destination for Schubart after his arrest, according to him, had in fact been Hohentwiel, but orders were received during the journey to take him to Hohenasperg instead, for which, Schubart tells us, he somewhat prematurely 'thanked God'. Perhaps the plan to deal with Schubart was worked out whilst the chaise was still en route. But who better than the zealous despot Rieger to show Schubart the path to his salvation?

Pietist abasement

Colonel Rieger began to visit Schubart regularly. The prisoner, driven to despair by boredom and loneliness, looked forward gratefully to his visits – or so he said later. Rieger supplied his prisoner with food, drink and medical care. He would inform Schubart of the contents his letters, albeit without allowing him to read them or to reply to them directly. In return, Schubart had to endure Rieger's Pietist lectures – a hard bargain indeed. Pietism would be the key instrument used to neutralise this troublemaker.

For the Pietist, our worldly destiny is entirely of our own making; we pay in this world for our errors and the flaws in our character; our suffering for those errors is always just and deserved; redemption comes only through spiritual self-examination, reflection and self-correction. Württemberg was one of the two main centres of Pietism in Germany at the time.

Rieger's life could be taken almost as a model for Pietist theories: during his confinement in the Hohentwiel dungeon, alone with his Bible, he had performed his spiritual exercises, prayed, reflected, even composed religious songs. After the first terrible year his conditions gradually improved until finally his release came. A few years later he was completely rehabilitated by Carl Eugen. What better evidence could there be, especially to someone of Rieger's vanity and self-regard, for the value of Pietist self-correction?

In Schubart's case, the fault for his incarceration and suffering was therefore entirely his own – not Carl Eugen's, not Rieger's nor the many influential enemies that Schubart had made. Schubart was to be made to look into his own black soul and blame himself for everything that had gone wrong with his life.

In his cell in Hohenasperg Schubart was subjected to frequent doses of Pietist moralizing and then left alone for long periods in physical squalor to brood on his spiritual and moral squalor. In his autobiography Schubart described over many pages his mental descent, step-by-step, into self-knowledge and self-loathing, almost to the point of suicide. [Leben 2:159-184]

By the end of his year in the cell Schubart was a mental and physical wreck. The air was so damp that the nightshirt had rotted on his body. He could no longer walk. Even standing was difficult – he had to hold on to the wall to stop falling over. Had he been left in the cell much longer he would certainly have died. That, however, was not the plan. [Leben 2:203]

The clergyman's unfinished business

Feeling the hand of mortality upon him, Schubart had begun to ask Rieger whether he could be allowed to take communion. He had been excommunicated from the Lutheran church five years before in Ludwigsburg, an event which he had worn almost as a badge of honour. Now, in the lengthening dark of autumn and the long nights of winter, battered continually with Rieger's Pietism and plagued by his own hypochondria, his reconciliation with the church and with God became clearly much more pressing to him. However, his request for communion was refused for many months, a fact that reveals the true nature of his incarceration.

Schubart's treatment in his first years in Hohenasperg was not just the result of the autocratic despotism of Duke Carl Eugen or the studied cruelty of Colonel Rieger, but a carefully measured process of religious 're-education' orchestrated by the third man in this triangle, Special Zilling (1723-1799). 'Special' was a title sometimes applied in the Lutheran church at that time to a position otherwise known as Superintendent or Deacon. Whatever he was called, he was in fact the head of the Lutheran Church in Ludwigsburg. Zilling was also the man who had been personally responsible for Schubart's excommunication in 1773.

Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, engraved by Christian Jakob Schlotterbeck, 1785. Image: ©Tobias-Bild Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen.

Of Schubart's appearance his son Ludwig tells us:

In his face the chin, mouth, nose, eyes and eyebrows were very close together. He would joke that this was an external indication of the quickness of his spirit and the operations of his will. His eyes kept their fire until his final days and lit up or shimmered with emotion. His forehead was high and wide; between the eyebrows a crease that was always present; the circumferance of his head so great that the hatmaker could use none of his usual forms. He was proud of the hair that grew so thickly on the back of his head. [Karakter 2f.]

Eight years before his arrest, in 1769, Schubart, by then an extremely talented and renowned musician, had applied for the post of Organist and Music Director at the court of Carl Eugen in Ludwigsburg.

Two bodies were competing for the right to nominate the candidate for this important post: the secular administration in the person of the Magistrate, and the church authorities in the person of Special Zilling. In the end it was the secular authorities who were allowed by Carl Eugen to choose the occupant of the post. It seems clear that the Duke would certainly prefer a candidate who would add even more glitter to the artistic splendour of his court, both religious and profane, over one whose main qualification was his worthy piety. Schubart, the secular candidate, was appointed and Zilling's candidate rejected. Zilling did not forget this slight.

Schubart threw his heart into the job, relishing his new public profile and much enlarged audience. His virtuoso performances in church were so spectacular that they attracted large congregations to listen to the music. Unfortunately for the preacher, many mambers of the large congregation would enjoy the music and then discover that they had pressing business elsewhere during the heavyweight piety of the lengthy sermon, then return for the concluding music when the preacher had finished. [Karakter 63.]

For Zilling, the music Schubart played was far too worldly and enjoyable – an unacceptable pleasure for the Pietist nature.

Schubart was not alone in his dislike of Zilling – we do not have to take just his word for Zilling's pompous and gloomy nature. Friedrich Wilhelm von Hoven, from whom we shall hear later in connection with the meeting between Schubart and Schiller, had the special misfortune as a ten-year-old to be sent to Zilling for instruction:

[Zilling] never missed an opportunity to exhort me to conduct myself with propriety, usually concluding with the admonition that I should not associate with silly and badly raised boys – whom he called 'evil lads'. As a result of this my circle of friends became more and more limited. Without doubt I would have ended up as a gloomy oddity or even a pious head-hanger, had not my father restricted my visits to Zilling in time. […]

Zilling was never able to win the affection of the people of Ludwigsburg. He had been born there as the son of a baker, which prejudiced people against him from the beginning. He made things worse by using affectations of his own importance to distract from the lowliness of his birth, but above all by his manner of preaching: most of his sermons were of the hellfire and brimstone sort. He criticised everything he thought unfitting for a Christian life: dancing at church consecration festivals, taking part in masquerades, even visiting the theatre. Those who felt they were the targets of these admonitions turned against him, none more so than the now-famous Schubart.

Schubart's public attacks and expressions of contempt for Zilling's hypocrisy caused my father to suspend my sessions with Zilling and to counteract the dark effects Zilling had had on my personality by taking me to the theatre, to wire-walking performances, to the Venetian Market during the Carnival in Ludwigsburg, where even children could wear masks. At the same time he gave me much more freedom to choose my schoolfriends, which cheered me up as much as the former restrictions had depressed me.

Hoven 20f.

Throughout Schubart's time in Ludwigsburg, from the autumn of 1769 to May 1773, Zilling, who was Schubart's immediate superior, took every opportunity of revenge on him. He started almost as soon as Schubart arrived, as we see in a light-hearted letter of Schubart's to his brother-in-law, Böckh, in January 1770:

I can think of no outrages – apart from a few things that are held to be treasonable offences in these parts. Firstly, I smoked a pipe of tobacco in the Post. Secondly, I looked around with opera glasses in a concert and thirdly, it is said of me that I speak to people too passionately and that I have the cheek to express opinions.

Briefe 1:157f

During his three years at the court Schubart's 'outrages' in the 'Swabian Sodom' of the Ducal court in Ludwigsburg became more and more outrageous. Our hero had many unorthodox sides to his nature. It was only a matter of time before Zilling, we would assume with some gratification, finally excommunicated him, which made it impossible for him to carry on as Organist. He was accused of 'a suspicious dalliance with a girl', as Schubart himself puts it, and spent a brief spell in prison. He was expelled from Ludwigsburg in 1773. [Briefe 1:199] But now in Hohenasperg, only four years later, his case would land on Zilling's desk once again.

After Schubart's capture and transport to the fortress of Hohenasperg Carl Eugen effectively handed the case over to Rieger and Zilling. Whether the Duke himself came up with the plan we do not know – it was certainly a subtle political tactic with many advantages from the Duke's point of view. Today we would call it a cruel and unusual punishment, leaving the libertine in the improving hands of the his arch enemy Zilling and his Pietist instrument Rieger for a few years.

The noisy, annoying and disrespectful Schubart would be silenced and many important people would be grateful to the Duke for silencing him. There was 'almost no crowned head nor any prince on Earth', wrote Carl Eugen, 'who had not been brazenly attacked in his writings'. [Briefe 1:250]

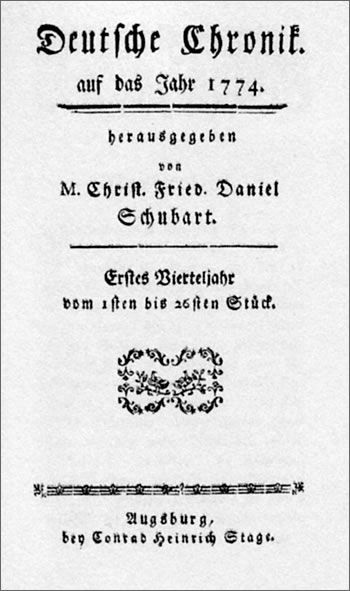

However, Schubart also had an artistic and above all journalistic reputation that was widely known within and far beyond Württemberg; 'burying alive' might work for someone relatively unknown or someone as generally hated as Rieger, but doing this to Schubart would lead to protests from many important directions. He had been producing his Deutsche Chronik, 'German Chronicle', for three years, writing it almost single-handedly, and in that short time it had established itself as a national journal with a circulation of more than 1,600 copies per issue and a European readership estimated at more than 20,000. It was an important factor in establishing that German identity which would play such an important part in the following two centuries.

The first edition of Schubart's Deutsche Chronik, 1774, published when he was in Augsburg.

There were legal niceties, too, one of which admittedly worked to Schubart's disadvantage. Schubart was not really a citizen of anywhere. In his odyssey around the tiny, fragmented German states of the time he had become a citizen of none of them and unwelcome in most. A legal process to establish who had jurisdiction over Schubart would be a wearisome task, by which time he would certainly have moved out of range.

Luckily for Schubart, if one can speak of luck in his miserable situation, in 1777 Carl Eugen was not the same man who had incarcerated Pyrker and Rieger. In his forties he had experienced a change of heart: he changed from being an autocratic despot to being an enlightened autocratic despot. The engine of the change seems to have been his mistress, later to become his second wife, Franziska von Hohenheim. Before she redirected his energies, Carl Eugen's life had been a byword for extravagant excess.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!