Albrecht Haller's poem Doris

Richard Law, UTC 2018-10-29 08:32

Metrics and measure

In our usual way we shall start our study of Doris by analysing the poem to death, leaving no hint of any poetic feeling behind. The text we are using is that of the sixth edition (1750) – for no particular reason. Here we go.

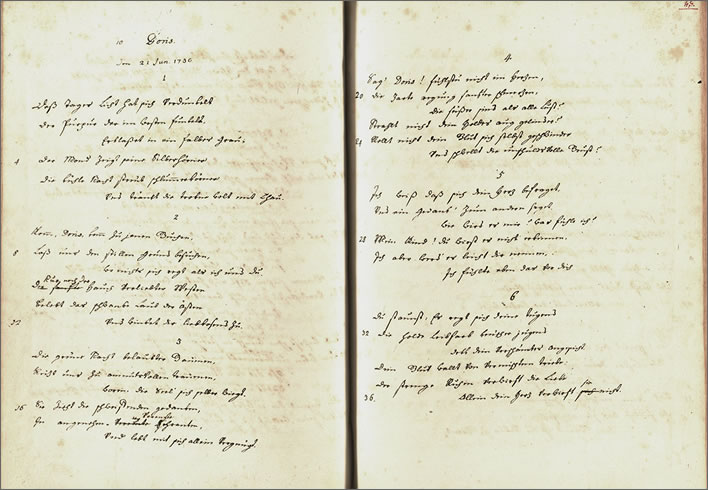

The first two pages of the autograph of Haller's poem Doris. Image ©Burgerbibliothek Berne.

Here is the first stanza of Doris:

Des Tages Licht hat sich verdunkelt,

Der Purpur, der im Westen funkelt,

Erblasset in ein falbes Grau;

Der Mond zeigt seine Silber-Hörner,

Die kühle Nacht streut Schlummer-Körner

Und tränkt die trockne Welt mit Thau.

The light of day has dimmed, the purple that glimmers in the west fades to a pale grey; the moon reveals its silver horns, cool night sows its seeds of sleep and sprinkles the dry world with dew.

Those who care about such things note that Haller has chosen the iambic tetrameter as his basic measure, each stanza a regular pair of three lines. The pair within the stanza are generally separated in meaning, in punctuation and in rhythm. Over the six lines of the stanza the rhyme scheme is a-a-b|c-c-b.

v — | v — | v — | v — | v

v — | v — | v — | v — | v

v — | v — | v — | v —

v — | v — | v — | v — | v

v — | v — | v — | v — | v

v — | v — | v — | v —

Here is a metrical markup of the first stanza. A blue highlight marks the 'long' or 'stressed' vowels (—), a green one the 'short' or 'unstressed' vowels (v) and a pink one the hypercatalectic vowels.

Des Tag|es Licht | hat sich | verdun|kelt,

Der Purpur, der im Westen funkelt,

Erblasset in ein falbes Grau;

Der Mond zeigt seiner Silber-Hörner,

Die kühle Nacht streut Schlummer-Körner

Und tränkt die trockne Welt mit Thau.

The first two lines of each pair are hypercatalectic, that is, they have an extra short syllable at their ends, the third line, however, is a strict tetrameter.

This arrangement has the effect of running the three lines together rhythmically, until the third line completes or fulfils the movement, achieving a satisfying closure for the reader.

Readers who are curious about this might care to make a metrical comparison of Haller's opening stanza of Doris with that famous English bucolic opening stanza of Thomas Gray's Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (c. 1750).

Gray gives us four complete iambic pentameters one after the other, each an individual statement – the commas at the line endings could just as well be full stops or semicolons:

The cur|few tolls | the knell | of par|ting day,

The low|ing herd | wind slow|ly o'er| the lea,

The plough|man home|ward plods | his wear|y way,

And leaves | the world | to dark|ness and | to me.

The metric professionals might also choose to bend poor Doris into a trochaic measure – but that really is merely a matter of opinion.

We note that unlike Klopstock, who introduced the innovation of equating long German vowels with long Greek/Roman vowels and who was writing in very strict, unrhymed structures, Haller is writing mainly stressed verse and does not shrink from using a short vowel ('Licht') in a stressed position. His verse is also rhymed, which means it is almost impossible for him to do what Klopstock will do with vowel length.

Others have used a similar scheme to that in Doris, notably Haller's contemporary Friedrich von Hagedorn (1708-1754) (in, for example, An die Dichtkunst). The association with Hagedorn, the great German anacreontic poet, is not entirely out of place, as we shall see at the appropriate moment.

In this particular stanza, your translator capitulated over that fine old German adjective falb in falbes Grau and, wanting to avoid all affectation, simply wrote 'pale'. But falb has echoes of weakening, decay and autumnal fading (= losing colour) which the pale 'pale' lacks. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in their Deutsches Wörterbuch (Leipzig 1854) tell us that falb also sounds 'somewhat refined, more elevated'.

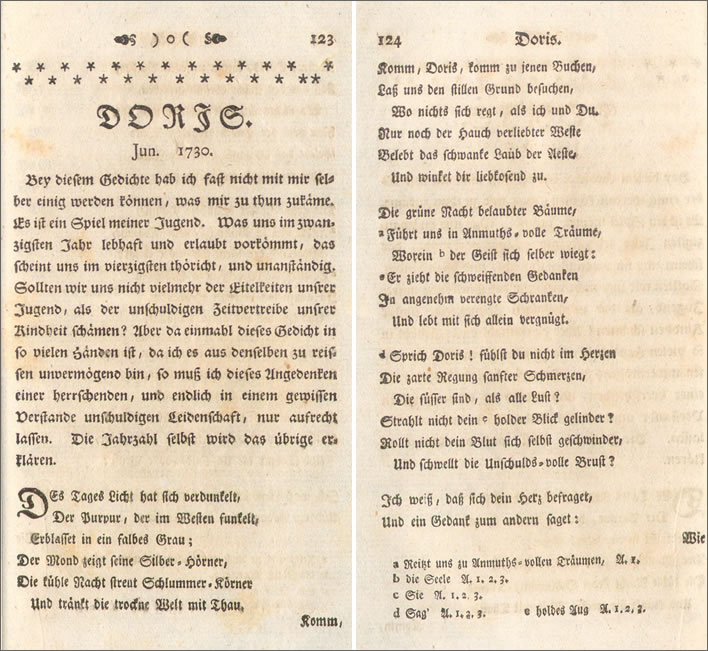

The first two pages of the Haller's poem Doris from the sixth edition.

Setting the scene

Komm, Doris, komm zu jenen Buchen,

Laß uns den stillen Grund besuchen

Wo nichts sich regt, als ich und Du.

Nur noch der Hauch verliebter Weste

Belebt das schwanke Laub der Aeste,

Und winket dir liebkosend zu.

Come, Doris, come to those beeches, let's visit the still glade where nothing moves but you and I. Only the breath of the loving west stirs the delicate leaves of the branches to wave caressingly at you.

The first stanza set the time as dusk. The second stanza now sets the place as a beech glade in a gentle evening breeze. This stanza also introduces the two participants, Haller and his Doris.

With the possible exception of the first stanza, the entire poem is a monologue of Haller's to Doris. In a traditional anacreontic we would expect the loved one to be addressed in the opening lines and then the rest of the poem would expand into poetic rhetoric far removed from the tenor of direct speech.

Ben Jonson (1572-1637) shows us how anacreontic poets write such things: 'Come my Celia, let us prove,/While we may, the sports of love.' (from Volpone, 1605). Delightful – but song, not speech.

Haller, in contrast, is always speaking directly to Doris – and the language used is not that of poetic figuration but of direct speech. This means that the poem is written without verbal affectation, in a clear language that is appropriate to the spoken nature of the work. Even at those times when the language becomes elevated – 'the breath of the loving west' – it does not strike us as being out of place.

This is the sort of language that, to paraphrase the American Modernist poet Ezra Pound, could under the force of some emotion be actually spoken by someone in Haller's era. Johann Georg Sulzer, in his influential textbook Theorie der Dichtkunst (1788), taking the first line of the second stanza of Doris– Komm, Doris, komm zu jenen Buchen, 'Come, Doris, come to those beeches', remarked on this 'friendly' language, that could be easily heard in the mouth of 'a mother speaking to her child in the field'.

In all that I have read about Haller's Doris, the remarkably skilful first three lines of this stanza are the most quoted. They combine spoken immediacy with a beautifully executed metrical flow across the enjambment between the second and third lines that is urging and persuasive.

Haller's phrase das schwanke Laub der Aeste tempts the translator (and probably many German-speaking readers) with thoughts of the widespread and ancient verb schwanken, 'to rotate/stir/swing'. But Haller is using the adjective schwanke, which has an equally ancient (Middle High German at least) meaning of 'thin/weak/meagre'.

He has already expressed the motion of the leaves with belebt, 'animates/stirs' and winket, 'waves/stirs' – yet more stirring and rotating would be too much of a good thing.

No, Haller the botanist, the accurate observer, is alluding to the lightness and thinness of beech leaves, which turn in the slightest breeze. After a moment's temptation with the arty 'diaphanous', your translator recovered his senses and wrote 'delicate'.

Again and again in Doris we shall come across instances of Haller's careful precision with words and his ability to describe scenes in a completely consistent way. It seems clear that the poet in Haller would have enjoyed using the adjective schwanke, with all its other not-quite allusions of twisting and waving.

This is poetry that demands slow reading and, if possible – like Anna Maria Hirzel – committing to memory. Then, stuck in a packed commuter train, delayed and torrid, you, too, can visit the beech glade with Haller and his Doris.

Die grüne Nacht belaubter Bäume,

Führt uns in Anmuths-volle Träume,

Worein der Geist sich selber wiegt:

Er zieht die schweiffenden Gedanken

In angenehm verengte Schranken,

Und lebt mit sich allein vergnügt.

The green night under the leafy trees leads us into graceful dreams, into which the spirit rocks itself: it keeps the straying thoughts in pleasantly narrow bounds and is content with itself.

This stanza focuses the location of the poem: we have moved from the relatively generic 'still glade' to the 'green night' underneath the trees – a beautifully concise formulation that arises naturally and without effort from the previous scene. There we were in a 'pale grey', moonlit twilight; here we have entered into the 'green night' under the trees – quite magical.

Your translator apologies for mutilating Haller's elegant genitive 'green night of the leafy trees' with 'under', but it reads much better in English; read it as 'of' if you prefer.

Readers may remember the cognate image 'tunnel of green gloom' under the chestnuts in Rupert Brooke's Grantchester. The reader might like to compare Brooke's weak 'tunnel of green gloom' with Haller's immeasurably better 'green night'

What follows in the next lines is a masterclass in poetic logic (there is indeed such a thing). The 'green night' is not just a nice metaphor: it leads us to 'graceful dreams'. Compare this precision to the shambles of Brooke's 'tunnel of green gloom' that is somehow 'green as a dream', although it is in fact the chestnut trees that are sleeping.

Haller's dreams are those into which the spirit 'rocks itself', as in a cradle – the German verb wiegen means gently to rock a cradle, die Wiege. In his numerous revisions Haller sometimes used Geist, 'spirit', sometime Seele, 'soul': it doesn't matter, as his own indecision shows. Once we follow the cradle metaphor, the following three, initially slightly puzzling lines, now form a beautiful extension of the metaphor: We imagine the baby, wrapped in the comforting security of swaddling bands, the constraints to straying thoughts, leading to innocent contentment. That is: night — dreams — rocking cradle — innocent contentment.

The man's a genius.

The permissibility of love

Sprich, Doris! fühlst du nicht im Herzen

Die zarte Regung sanfter Schmerzen,

Die süsser sind, als alle Lust?

Strahlt nicht dein holder Blick gelinder?

Rollt nicht dein Blut sich selbst geschwinder,

Und schwellt die Unschulds-volle Brust?

Speak, Doris! Don't you feel the gentle stirring of soft heartaches that are sweeter than all desires? Does your sweet glance not shine more mildly? Does your blood not flow faster and does not the innocent breast swell?

We now move from the scene-setting of the first three stanzas of the poem into the innards of Haller's monologue with Doris.

The exhortation 'speak, Doris!' expresses the suitor Haller's desire to know her mind, but speaking is something that Doris never does throughout the entire poem. She says not a word, as we shall see.

As for the 'gentle' and 'sweet' Schmerzen, 'pains', these are the enjoyable sufferings of love that have been popular down the centuries in German-speaking countries. The Schubert fans among our readers will be able to think of many instances of delightful suffering – the first that comes to mind is Rückert's Lachen und Weinen, set to music wonderfully by Schubert as D 777. We must also remember that Haller was a man and a poet, like Klopstock, of great Empfindsamkeit, 'feeling, sensitivity, empathy'. He tells us himself that he often burst into tears at some thought or other.

Ich weiß, daß sich dein Herz befraget,

Und ein Gedank zum andern saget:

Wie wird mir doch? Was fühle ich?

Mein Kind! du wirst es nicht erkennen,

Ich aber werd es leichtlich nennen,

Ich fühle mehr als das für dich.

I know that your heart is questioning itself and one thought is saying to another: what is happening to me? what am I feeling? My child! You will not recognise it but I can name it easily, I feel more than that for you.

Now we come across a quite remarkable change in point of view. Haller establishes Doris' chastity, her purity in both thought and action by describing the turmoil of her present emotions.

Doris could at any point have become a traditional anacreontic, in which the poet attempts to get the girl to drink up and give in, on the basis that time is running out for her (see Ben Jonson, above). In Doris, even though the girl does not speak to us directly, her mental state is acnowledged and described, which is a major advance on anacreontic poetry.

The anacreontic poets in general are not too bothered about what the girl thinks or feels; their narrow goal is to achieve final legover-status within as few stanzas as possible.

Haller, in this edition of the poem, allows himself a total of twenty-four stanzas; three of these are scene-setting, as we have seen; thirteen – much more than half – are exercises in the psychological investigation of the girl's state of mind. We can understand why Anna Maria Hirzel recited this poem so enthusiastically. This is Empfindsamkeit at work.

We are going to come up against a lot of chastity in Doris. Following the Reformation, the Protestant regions of the Confederacy, of which Berne was one, moved into an ethos of extreme chastity and prudery. We discussed this in connection with Klopstock's ode Der Zürchersee, in respect of the scandal of his mixed-sex boat journey on the Lake of Zurich in 1750.

In such a culture, Haller's task is not just to woo Doris for himself, but also to convince her of the permissibility of such emotions as love – to bring her to acknowledge them. Doris is in fact a love poem in the narrowest meaning of the term. It is also, for those with eyes to see, a moral work of some significance – almost inaccessible from the position of our modern depravity.

Du staunst; Es regt sich deine Tugend,

Die holde Farbe keuscher Jugend

Deckt dein verschämtes Angesicht:

Dein Blut wallt von vermischtem Triebe,

Der strenge Ruhm verwirft die Liebe,

Allein dein Herz verwirft sie nicht.

You ponder; your virtue stirs, the soft colour of chaste youth covers your bashful face: your blood stirs with confused desires, your good reputation rejects love, only your heart does not dismiss it.

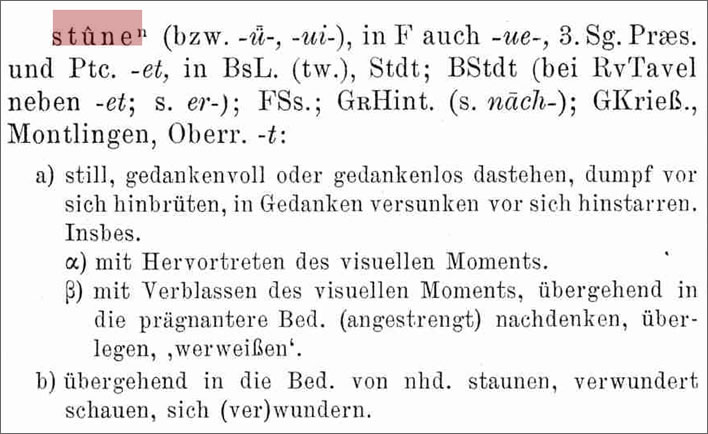

The phrase Du staunst not only puzzles today's readers, it seems to have puzzled the Teutonic readers of Haller's time, because Haller added a footnote explaining his use of this phrase for those who did not speak a Swiss dialect. The Teutons read staunen here as 'shock/amazement', whereas in Haller's Swiss dialect, as the magnificent Schweizerisches Idiotikon tells us, stûne, (pron. 'stoone', 'doo stoonscht') means 'to stand there quietly, either filled with or empty of thoughts'.

Completing the circle, the Idiotikon quotes these lines of Haller's and his footnote as an instance of this usage; it also specifically locates the usage in the area around Basel and (Swiss) Freiburg. Haller wrote:

I retain this old Swiss word resolutely. It is the root of Erstaunen, 'amazement/stupor', and means rever, 'dream', a word that can be given with no other German word.

Dieses alte Schweitzerische Wort behalte ich mit Fleiß. Es ist die Wurzel von Erstaunen, und bedeutet rever, ein Wort, das mit keinem andern Deutschen gegeben werden kann.

The phrase Der strenge Ruhm will also puzzle speakers of modern German, for whom the meaning of the noun der Ruhm has degenerated into merely 'fame'. In Haller's time it also meant 'reputation', which here combined with streng, 'strict/severe' means Doris' good reputation/name.

Mein Kind erheitre deine Blicke,

Ergieb dich nur in dein Geschicke,

Dem nur die Liebe noch gefehlt.

Was willst du dir dein Glück missgönnen?

Du wirst dich doch nicht retten können,

Wer zweifelt der hat schon gewählt.

My child, lighten your look, just surrender to your destiny, from which only love is still lacking. Why do you want to begrudge your own happiness? You will not be able to save yourself – those who doubt have already chosen.

Haller's excellent phrase Wer zweifelt der hat schon gewählt, 'who doubts has already chosen' deserves to be known more widely. Haller is using the argument of the religious moralist in a cunning sense against Doris. The morally pure person does not doubt, since doubt indicates the knowledge of sin, thus doubt is almost as bad as the commission of the sin itself. 'Doubting Thomas', John 20:24-29, gets away with a ticking off: 'be not faithless, but believing'.

Haller is laying the ground for the argument that runs through Doris, that is, for the permissibility of love and the validity of pleasure. In Pietist/Calvinist theology, pleasure is always a suspect emotion.

Our readers may recall the touching scene described by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739-1791), when he watches from a window of his prison cell a mother and child dancing wildly to a piper under lime tree – after years of incarceration and Pietist brainwashing Schubart had not been broken: he was still able to assert that pleasure is a permissible emotion for humans.

Der schönsten Jahre frühe Blüthe

Belebt dein aufgeweckt Gemüthe,

Darein kein schlaffer Kaltsinn schleicht;

Der Augen Glut quillt aus dem Herzen,

Du wirst nicht immer fühllos scherzen,

Wen alles liebt, der liebet leicht.

The early bloom of the most beautiful years animate your awakened feelings, through which no coldness creeps; the glowing ardour of your heart wells up in your eyes, you will not always flirt unfeelingly, whoever is loved by everybody, loves easily.

Haller uses scherzen– its modern meaning almost exclusively 'to joke' – in one of its old senses of 'to flirt' or 'to dally'.

Schubert fans will recall no doubt Leitner's Des Fischer's Liebesglück (D 933) in which the romantic liason of the fisherman and his love is der stillen, unschuldigen Scherz, 'the quiet, innocent dalliance'.

Haller closes the stanza with an aphorism which may cause trouble for non-native speakers. The word alles can mean not only a totality of things but also of persons – the more usual personal form, Wen alle lieben, would have broken the metrical scheme, however, so alles it is.

Wie? sollte dich die Liebe schrecken!

Mit Schaam mag sich das Laster decken,

Die Liebe war ihm nie verwandt;

Sieh deine freudigen Gespielen!

Du fühlest, was sie alle fühlen;

Dein Brand ist der Natur ihr Brand.

What? Should the thought of love frighten you! Shame may cover up vice, but love was never its kindred; Look at your happy friends! You are feeling what they all feel; your fire is just the same as theirs.

In differentiating the innocence of love from the shame of vice Haller strikes another blow at Pietism.

O könnte dich ein Schatten rühren

Der Wollust, die zwei Herzen spüren,

Die sich einander zugedacht,

Du fordertest von dem Geschicke

Die langen Stunden selbst zurücke,

Die dein Herz müßig zugebracht.

If only a shadow of the passion could stir you, that two hearts feel who are intended for each other, you would demand from your destiny the return of the long hours your heart spent in idleness.

Paraphrasing: once Doris allows herself to experience passionate love she will bitterly regret the long hours she had spent up to now without it.

Although his basic tendency is to let each line stand on its own, Haller quite frequently uses enjambment, that is, he runs lines together across line boundaries. In this stanza it is essential to give the enjambment its due: lines 1-3 should be read without break, lines 4-6, too. The whole stanza forms a single conditional sentence: lines 1-3 are the protasis, lines 4-6 the apodosis.

Musing on fordertest/zurücke will bring much innocent pleasure into the otherwise lonely lives of the fans of German grammar.

Wann eine Schöne sich ergeben

Für den, der für sie lebt, zu leben,

Und ihr verweigern wird zum Scherz:

Wann, nach erkannter Treu des Hirten,

Die Tugend selbst ihn kränzt mit Myrten,

Und die Vernunft redt wie das Herz.

When a beautiful girl surrenders herself to live for him who lives for her and her refusal becomes a game: when after the acknowledged fidelity of the shepherd, virtue herself crowns him with myrtle and reason speaks like the heart.

This stanza is the first of a series of three which begin with Wann, 'if' (in an older, rustic sense). In fact, the situation is even more marked, in that in the first two stanzas, even the second line group is introduced with wann. The group is therefore a sequence of five protases with a final apodosis at its conclusion. The five protactic statements form, in fact, a list of the symptoms of a diagnosis of love made by the medical doctor Haller.

Wann zärtlich Wehren, holdes Zwingen,

Verliebter Diebstal, reizends Ringen

Mit Wollust beyder Herz beräuscht,

Wann der verwirrte Blick der Schönen,

Ihr schwimmend Aug, voll seichter Thränen,

Was sie verweigert, heimlich heischt,

When tender resistance, gentle insistence, loving theft, delightful wrestling, intoxicates both hearts with passion, when the confused gaze of the beautiful one, her moist eyes full of superficial tears, what she refuses, secretly desires.

Our modern, degenerate days now know no courtship rituals which would not provide good cause for a police investigation. In Haller's time things were much more straightforward, as this stanza has shown us.

Wann sich … allein, mein Kind, ich schweige

Von dieser Lust, die ich dir zeige,

Ist, was ich sage, kaum ein Traum;

Erwünschte Wehmuth, sanft Entzücken!

Was wagt der Mund euch auszudrücken?

Das Herz begreift euch selber kaum.

When … my child, even though I am silent about this passion that I show you, what I say is hardly a dream. Longed-for melancholy, soft delight! How dare the mouth express you? The heart scarcely understands you itself.

Despite the high philosophical level of Haller's exposition, the language which carries it never strays far from the spoken language. The first half of this stanza, with its sudden ellipsis introducing an interjection, is characteristic for oral language. The protasis is 'when what I say is scarcely a dream'.

The second half of the stanza is an apodosis that concludes the five protactic statements. It is easier to understand when we note that euch, 'you', refers to 'longed-for melancholy, soft delight'.

Du seufzest, Doris! wirst du blöde?

O selig! flößte meine Rede

Dir den Geschmack des Liebens ein.

Wie angenehm ist doch die Liebe?

Erregt ihr Bild schon zarte Triebe,

Was wird das Urbild selber seyn?

You sigh, Doris! Are you weakening? O bliss! my words are giving you the taste of love. How pleasant love is really? Your image arouses tender desires, what will the archetype of that be?

The modern speaker of German will be shocked to find Haller asking Doris if she is becoming blöde, since its modern meaning is exclusively 'stupid', 'foolish', 'idiotic' and so on. An old, Middle High German meaning of blöd/blöde was 'physically weak', a meaning that was retained in Swiss dialect (Idiotikon).

Haller's play on Bild and Urbild is rather exotic for today's taste. Paraphrasing: if the image has such a powerful effect, how powerful must the original be?

Mein Kind, geniesse deines Lebens,

Sey nicht so schön für dich vergebens,

Sey nicht so schön für uns zur Qual.

Schilt nicht der Liebe Forcht und Kummer,

Des kalten Gleichsinns eckler Schlummer

Ist unvergnügter tausendmal.

My child, enjoy your life, don't be so beautiful for nothing, don't be so beautiful that it is a torment for us. Don't moan at love's fear and sorrow, the repellent slumber of cold apathy is a thousand times more unpleasant.

Zu dem, was hast du zu befahren?

Laß andre nur ein Herz bewahren,

Das, wers besessen, gleich verläßt;

Du bleibst der Seelen ewig Meister,

Die Schönheit fesselt dir die Geister,

Und deine Tugend hält sie fest.

And anyway, what do you have to fear? Let others keep a heart, which, whoever possesses it, leaves them straight away; you remain the permanent master of your soul, beauty enchains the spirits and your virtue holds them tight.

Choosing the suitor

Erwähle nur von unsrer Jugend,

Dein Reich ist ja das Reich der Tugend,

Doch, darf ich rathen, wähle mich.

Was hilft es, lang sein Herz verhehlen?

Du kannst von hundert edlern wählen,

Doch keinen, der dich liebt, wie ich.

Choose from our young people, your domain is the domain of virtue, but, may I counsel you, choose me. How does it help to deny your heart? You can choose from a hundred more noble men, but none of them loves you as I do.

With this stanza the poem now changes direction. The previous 13 stanzas have been an attempt to persuade the chaste Doris to accept the legitimacy of her own feelings of love; the next seven stanzas attempt to persuade Doris to love Haller in particular.

Ein andrer wird mit Ahnen prahlen,

Der, mit erkauftem Glanze strahlen,

Der, malt sein Feuer künstlich ab;

Ein jeder wird was anders preisen,

Ich aber habe nur zu weisen

Ein Herz, das mir der Himmel gab.

One will boast of his ancestry, another will glitter with bought lustre, another paints his fire artificially; each one will boast of something or other, I can only show a heart that was given to me by Heaven.

As we discuss in more detail in part three, Haller was repelled by the social and cultural conditions he found in Berne. The account he gives in this and the following three stanzas of his competitors for the hand of Doris is therefore not very flattering.

Trau nicht, mein Kind, jedwedem Freyer,

Im Munde trägt er doppelt Feuer,

Ein halbes Herz in seiner Brust:

Der, liebt den Glanz, der dich umgiebet,

Der, liebt dich, weil dich alles liebet,

Und der, liebt in dir seine Lust.

Do not trust, my child, those suitors with double fire in their mouths but only half a heart in their breasts: one who loves the lustre that surrounds you, one who loves you, because you love everything and one who loves in you his own lust.

Ich aber liebe, wie man liebte,

Eh sich der Mund zum Seufzen übte,

Und Treu zu schweren ward zur Kunst.

Mein Aug ist nur auf dich gekehret,

Von allem, was man an dir ehret,

Begehr' ich nichts als deine Gunst.

I love in the way one loves before the mouth becomes practised at sighing and swearing faithfulness becomes an art. My eyes are only set on you, from everything that one reveres in you, I desire nothing other than your favour.

Mein Feuer brennt nicht nur auf Blättern,

Ich suche nicht dich zu vergöttern,

Die Menschheit ziert dich allzusehr:

Ein andrer kann gelehrter klagen,

Mein Mund weiß weniger zu sagen,

Allein mein Herz empfindet mehr.

My fire burns not just on paper, I am not trying to idolize you, humanity adorns you more than enough: Others can plead more learnedly, my tongue has less to say, but my heart alone feels more deeply.

Wann ungetheilte Brunst im Herzen

Wann lang-geprüfte Treu in Schmerzen,

Wann wahre Ehrforcht dir gefällt;

Wann für ein Herz dein Herz sich giebet,

So bin ich schon der, den es liebet,

Und der Glückseligste der Welt.

If unshared fervour in the heart, if long-tested fidelity in pain, if true respect please you; if your heart gives itself for another heart, then I am the one whom it loves and the happiest man in the world.

After the denigration of her other admirers, this stanza and the one that follows it are Haller's final recommendation of himself as Doris' suitor.

Mein Kind! erkenne meine Flammen,

Dein holdes Aug, aus dem sie stammen,

Kennt sie nach langer Prüffung schon:

Hab ich dir immer treu geschienen,

So leide, daß ich dir darf dienen,

Ein einig Wort ist gnug zum Lohn.

My child! acknowledge my flames, your gentle eye, from which they originate knows them already from long examination: have I always appeared faithful, so earnestly that I may serve you, a single word is sufficient reward.

The answer

Was siehst du forchtsam hin und wieder,

Und schlägst die holden Blicke nieder?

Es ist kein fremder Zeuge nah:

Mein Kind, kann ich dich nicht erweichen?

Doch ja, dein Mund giebt zwar kein Zeichen,

Allein dein seufzen sagt mir Ja.

Why do you look so anxiously back and forth, and look down with your sweet gaze? No strangers are nearby: My child, can I not soften you? But yes, although your mouth indeed makes no sound, just your sigh says Yes to me.

If you expect the poem to end with a climactic scene in which the two lovers fall into each others' arms, you are in the wrong poem. Doris has not uttered one word; the best Haller gets from her is a sigh. We have reached the great crescendo of feeling and sensitivity that characterises the poetry of Empfindsamkeit, of which Doris is such a leading example. Doris' response is pure emotion, beyond all carefully composed textualisation.

Pure emotion, but expressed and communicated in physical facts. Haller the scientist, the empirical observer, the medical doctor, notes the symptoms of the case. His report is factual, lacking all abstraction – and deeply moving because of that.

Any of the Modernist poets who came two centuries later – for example, Eliot in English and Benn (also a medical doctor) in German – would have been proud to have written such lines, Eliot's 'objective correlative' made manifest.

Haller leaves the rest to a single-sentence footnote:

On 19 February 1731 the author married Marianen Wyß von Mathod und la Mothe.

Den 19. Febr. 1731. heyrathete der Verfasser Marianen Wyß von Mathod und la Mothe.

Some final thoughts, not comprehensive

Haller's poetry is not mimetic. You will not find its predecessor, nor any successors. Only Haller could write Haller's poetry. There are shared traditions of his time, but there is no poet or group of poets to whom one can point and say 'Haller descended from them'.

He destroyed his juvenile work – and that was probably a good thing, because he appears to have broken with that completely. The poetry he wrote from his time in Basel (1728) and the death of his second wife and son – the time when he effectively stopped writing poetry (c. 1741) – was uniquely Haller.

Swissness

During our close reading of Doris it became clear that it is not for nothing that Haller titled his collection of verse Versuch schweizerischerGedichte. Haller said, when defending himself from the Teutonic grammarians and systematisers of his time such as Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700-1766), at first his friend then his great enemy, that his mother tongue was not German but Bärndütsch, the variant of the Swiss-German dialect spoken in and around Berne.

For him German was as much a foreign language as French, which he wrote with equal fluency, having lived during his time in Biel and Basel, both of which are on the language border between Swiss-German and French speaking 'Switzerland'.

Swiss-German dialects form an independent language with local colourings. Haller's language, Bärndütsch is a very independent member of that independent family. The special character of this language is easy to demonstrate. In 1921 the Bernese teacher Albert Meyer (1893-1962) read the Odyssey in Greek and realized that Homer's compact hexameters could be rendered comfortably into Meyer's mother tongue, Bärndütsch. In 1956, after around thirty years of labour, he produced a complete rendering of the Odyssey in Bärndütsch. He didn't live to fulfil his plan of a translation of the Iliad. This translation was done instead by Walter Gfeller and published in 1981.

Swiss-German dialects, when spoken in their original intensity and not in the modern forms, infected by written German, have as their main features brevity and the directness of oral expression, exactly the qualities we find in Haller's writing. It is no accident, either, that one of the most laconic of the Swiss-German dialects is in fact Berne-German.

Haller was born into Bärndütsch and Bärndütsch was born into him. His writing style, whether in poetry, philosophical or scientific tracts, has all the virtues of that language: brevity, a steadiness, which in the spoken language others associate with slowness, and an avoidance of all floridity.

No canonical text

We must say a few words about Haller's perfectionism. He was primarily a scientist and not a poet. This fact probably leads to his most annoying trait as a poet, his habit of revisiting his works and tinkering with them. We like our poets to flutter like butterflies from flower to flower – and not return. Haller's butterfly came back again and again.

From edition to edition he changed words and phrases, added some stanzas and deleted others, then, at a later date, deleted or amended some of the added material again. The scientist in him did not just tinker, he documented his tinkering in appendices to each edition containing lists of changes. From edition to edition even this list changes. Anyone who thinks that Haller was a scientist foremost and a poetic dilettante second should consider the thought and care that Haller invested in the poetic process.

Some of this tinkering was intended to improve the poetic diction, most were reflections of the battle that continued throughout his life between those who were attempting to codify, systematise and purify the German language (e.g. Gottsched) and those who saw the validity of Haller's Swissness (e.g. Bodmer). At a number of points Haller just gave in to what, driven by the immense popularity of his verse, soon turned into an early 18th-century tweetstorm about this or that language error, but at a number of other points he dug in his heels.

It thus makes it very difficult to find a canonical text for any particular poem, largely because there isn't one. The gold standard for authoritative literary texts among philologists in this respect is always the edition 'letzter Hand', the 'author's last edition'. In Haller's case this edition happens to be just the last of a series of amendments, each one neither more nor less valid than the next.

Haller's immensely popular poetry went through many editions during his life, each tinkered with in some way or another. After his death the philologists got to work and did what they do best, that is, tinkered some more. Ludwig Hirzel's 1882 edition of Haller's poems contains a version of Doris and adds at the end of the book the absurdity of a page of alternative readings. Quite what Anna Maria Hirzel would have made of that as she recited Doris to Klopstock and the other boys and girls in the boat on the Lake of Zurich we can only guess.

Success and translations

His poetry touched a chord in the minds of his fellows, making him one of the most respected and widely read authors in the German-speaking world. During Haller's lifetime there were eleven authorised editions and many reprints. His poetry was translated into Dutch, English, French, Italian, Russian and Swedish. The English translation was done in verse by a certain Mrs J. Howorth, an amateur botanist, in 1794.

Howorth was clearly an agent of nemesis sent by the thousands of live animals on whom Haller had so hard-heartedly experimented, for her dreadful translation has ensured that Haller's poetry has since then remained unknown in the English speaking world. Having done her task she herself then faded from all record.

Those with strong stomachs can view and even download a copy of her work from the Bibliothèque nationale de France – Gallica.

Self-criticism

Albrecht Haller could be without doubt a difficult person – his professional genius took no prisoners. He wrote of himself in 1741:

How venomous, hateful, envious, insensitive, gossipy and critical I am!

Wie giftig, gehässig, neidisch, unempfindlich, nachredig, kritisch bin ich!

Haller's assessment of his own character may be accurate, but it is just as telling that he turns all these failings onto himself. His life was one of permanent self-examination; the examination became more bitter as he himself became more bitter – it was a fundamentally religious exercise that would have been familiar to the Catholic Loyola or the Protestant Calvin, but amplified by Haller's drive for scientific knowledge. He was much, much harder on himself than he was on other people. The isolation of his childhood and the castigation of his tutors had left him with probing, pitiless introspection as the foundation of his psyche.

This state of permanent introspection is the motor behind his constant fiddling with his poetic texts. For Haller, it wasn't enough to have written the most successful and widely read poetry of his generation throughout Europe, he had to continually revisit and revise it with near pathological intensity.

At the publication of an edition of his book of poetry in 1750 – the year that Anna Maria Hirzel was reciting it to Klopstock on the Lake of Zurich – the 42 year-old Haller said dismissively about his great poem Doris:

I could not easily decide what to do with this poem. It is a game of my youth. What seems lively and permissable to us in our twentieth year, now, in our fortieth, seems stupid and inappropriate. Shouldn't we rather be ashamed of the vanities of our youth rather than the innocent pastimes of our childhood? But since this poem is now in so many hands, from which I can no longer snatch it back, I have to leave this memory of a dominant and finally in a certain way innocent passion as it stands. The year explains all the the rest.

Bey diesem Gedichte habe ich fast nicht mit mir einig werden können, was mir zu thun zukäme. Es ist ein Spiel meiner Jugend. Was uns im zwanzigsten Jahr lebhaft und erlaubt vorkömmt, das scheint uns im vierzigsten thöricht und unanständig. Solten wir uns nicht vielmehr der Eitelkeiten unsrer jugend, als der unschuldigen Zeitvertreibe unsrer Kindheit schämen? Aber da einmal dieses Gedicht in so vielen Händen ist, da ich es aus denselben reissen unvermögend bin, so muß ich dieses Angedenken einer herrschenden, und endlich in einem gewissen Verstande unschuldigen Leidenschaft, nur aufrecht lassen. Die Jahrzahl selbst wird das übrige erklären.

At the time he wrote this Haller had been married to Amalia Teichmeyer for nine years; the couple had already produced six of their seven children. Haller had become a scientific phenomenon, was a member of most of the great learnèd institutions throughout Europe. The year before, the Emperor had conferred an hereditary title upon him. Those evening walks in the beech grove with his chaste Doris/Mariane had taken place twenty busy and painful years before.

He calls himself and his poem, in front of all his readers, 'stupid and inappropriate'; if he could, he would 'snatch it back' from them; even his great love for Mariane was downgraded to an 'innocent passion'. For the battered Haller it counted for nothing that readers across Europe were sighing moist-eyed at his courtship of Doris or weeping openly at his words on her loss barely five years later – Arcadia had returned to mock him for his presumption of happiness.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!