Life after Doris

Richard Law, UTC 2018-10-29 08:33

Berne: the Arcadian swamp

Albrecht Haller's time as a medical doctor in Berne started out as Arcadian: he had his belovèd Mariane, who bore him three children, Mariane (1 February 1732-1811), Ludwig Albrecht (18 January 1734-1738) and Gottlieb Emanuel (17 October 1735-1786); He was able to take a number of short tours into the Alps, continuing his scientific work; He was even writing poetry once more.

But Berne was not Basel. Over the centuries Berne had developed into a political and economic swamp run by patrician clans. Once again we have to remind the reader that we are not in the modern 'Switzerland'. In our reading of Doris we stumbled across hints of the vacuity of the other suitors that Doris had: the preening aristocrats, the boastful and the empty-headed – all Haller's bitterness and moral indignation can be heard in those lines.

Haller had a deep moral sense that was outraged by the conditions he experienced in Berne. It was made worse by the contrast with the hard, natural life and simple piety of the inhabitants of the alpine valleys whom he met on his tours. After each tour he returned from Eden and its high paradises into the degradation of the slough of despond that was the city of Berne at that time.

Disgust moved Haller to write a poem, Verdorbene Sitten, 'Rotten Morals', which described the situation in Berne as he saw it. His descriptions align with other accounts of the time; it is also clear that he had real persons in mind when populating his poem with unnamed malefactors.

Worst of all for Haller was the fact that the patricians who ran the city had next to no regard for scientific endeavour and its fruits. Haller's carefully catalogued herbaria and his treatises on botany and medicine were worthless pastimes for them. Haller's good reputation among his fellow citizens as a practising medical doctor was attained despite their misgivings at his dabbling in such things – he was that strange creature, a doctor who wrote poetry.

Volume 41(!) of Haller's Herbarium. Image ©Paris, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Herbier Haller.

Whilst Haller's reputation in Germany and the rest of Europe was soaring as a result of his studies, in Berne it brought him little recognition, rather mistrust. Feudal position, property, money and connections were all that counted in Berne at the time.

As the years in Berne passed, the situation there became intolerable for him. Just as in his childhood, where he had been driven by a deep need to excel, he found not only no recognition for his work but even mocking rejection. It was not the first time and will not be the last that the arcane knowledge of the man of learning was treated with suspicion by those around him. Haller, that most moral and deeply religious of men, gradually became the focus of all kinds of petty religious bigotry.

The situation became so bad that there was finally only one solution: to leave.

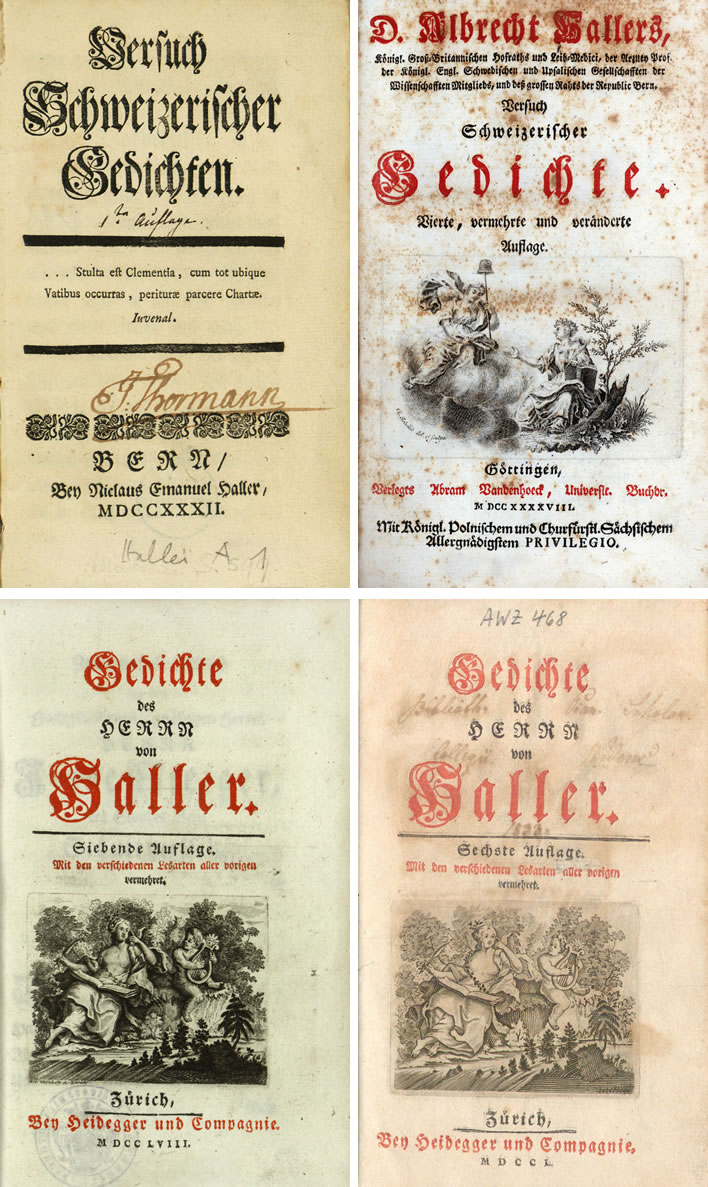

Haller's volume of poetry proved extremely popular, as the number of its editions in rapid succession demonstrates. Here, clockwise from top left: the first edition, printed in Berne in 1732, monochrome and without illustrations; the fourth edition, printed at the University Press in Göttingen in 1748, two-colours, illustrated; the sixth edition, printed in Zurich in 1750, two-colours, illustrated; the seventh edition, ditto in 1758.

Göttingen: professional success, family disaster

In 1736, after seven increasingly professionally frustrating years in Berne, Haller obtained a professorship at the new University of Göttingen. The university had been founded by the British monarch George II (who was also Prince-Elector of Hanover) between 1732 and 1734. After a last alpine tour in the summer of 1736, Haller arrived on 30 September in Göttingen.

The new university, striving to make its presence felt, now had Haller's restless vortex in its midst. A full listing of Haller's contributions to Göttingen is out of place here. Given what we know of Haller's energy, the reader will have no difficulty accepting the widespread belief that he helped raise the university to the first rank of scientific institutions within only a few years and that he also guided it in attracting some of the best available scientific talent of the age.

All Haller's great achievements in the seventeen years he spent at Göttingen, the endless labour and grinding drudgery, are made greater when set against the personal disasters that beset him from the very moment of his arrival.

His belovèd wife Mariane – 'Doris' herself – died of fever on 30 October 1736, just after their arrival in Göttingen. He had just turned twenty-eight. They had enjoyed only five years of marriage. The extremely moving Trauerode, 'Mourning Ode', that he wrote on her death counts as one of his greatest poetic works and left few dry eyes throughout Europe. It was one of his last major works.

It is a paradox, that, driven by his poems Die Alpen, Doris and now the Trauerode, his poetic reputation grew and grew from this moment on, the moment at which he effectively gave up writing poetry. There would only be one more serious poem from him, one that arose out of yet one more disaster.

In the Trauerode for Mariane he wrote of the sacrifices she made for him in leaving her family and friends behind in Berne: 'You left them, and chose me'. He had torn her from a 'loving Fatherland' – a phrase that is yet another indication of Haller's Bernese patriotism. He recalls how sad Mariane was whenever he set off on one of his alpine tours and how joyful and tender she was when he returned.

Despite the Empfindsamkeit we have discussed in connection with Haller, he kept his feminine side well hidden – his tears of passion for Mariane were kept secret and he realised only after he had lost her just how much he had loved her, but at the same time just how infrequently he had told her that.

After Mariane's death, Haller began a diary that came to document the dark night of the soul into which he now descended. It is characteristic for Haller's introspective and self-flagellating personality that he sought the origins for the loss of Mariane in failings of his own.

The next blow came only eighteen months after his wife's death. On 30 April 1738, his second child, Ludwig Albrecht, died. Only his daughter Mariane, who was to be long-lived (1732-1811), and his son Gottlieb Emanuel (1735-1786) were left him, the only reminder of that lost Arcadia.

Haller's professional successes in Göttingen and even his poetic successes were accompanied by the sort of low-level but steady fusilade of criticism that is not uncommon in academic environments even today. Haller's personality did not help: depressed from personal loss, plagued by ill-health, in constant creative turmoil, he was often abrupt or sarcastic. He had many friends and admirers who recognised his worth, but he had opponents, too. His lack of all tact and all diplomatic sense only made things worse. The young genius growing up in isolation had had no chance to learn such skills.

We must also remember that in Göttingen, even a person of such European dimensions as Albrecht Haller remained a stranger in a strange land. He was a citizen of Berne, the Bernese dialect of Swiss-German was his mother tongue, the German of Hanover was a foreign language. He occasionally had to point out this fact to those native German speakers who laughed at his German howlers.

We saw that, in his Trauerode on the death of Mariane, he writes of her isolation in Göttingen, but this isolation – linguistic and cultural – also applied just as much to Albrecht Haller himself.

He needed a respite from the treadmill of his own personality and the cabals of Göttingen; he needed a change from the location of the personal losses he had suffered so acutely. On the advice of friends in both Berne and Göttingen, he returned to Berne, die Heimat, in April 1739.

Berne: Elisabeth Bucher

In Berne there was an immediate and rapid improvement in his circumstances. Events moved quickly: on 9 May 1739 he became engaged to Elisabeth Bucher (1711-1740), the daughter of a Berne councillor. He was 30, she was 28 – for the time a relatively elderly bride: whether this was a marriage of political tactics is difficult to say. But like Mariane, Elisabeth was Bernese, spoke the dialect and was rooted in the same Heimat that meant so much to Albrecht. They married a month later.

Haller also undertook a number of short alpine tours that summer. Arcadia reasserted itself – but not for long. Haller's life was destined to be one of clouds rather than sunshine.

In July of 1739 he set off for Göttingen with his new wife, arriving on 22 August.

Albrecht Haller (c.37) in professorial gown by Johann Rudolf Studer, Berne, 1745. Image ©Burgerbibliothek Berne.

Elisabeth became pregnant, but the difficult childbirth killed her. She died after scarcely a year of marriage, on 4 July 1740. The child, Johann Rudolf, joined her in death only six months later.

Haller fell once more into a deep depression of lonely self-examination, much of which he confided to his diary. He had written an ode of mourning for Mariane, he now wrote one for Elisabeth.

Amalia Teichmeyer

In December of 1741 Haller married for the third time, Sophie Amalia Christina Teichmeyer (1722-1795). She was 19, Haller was 33. Her father was Hermann Friedrich Teichmeyer (1685-1744), the professor for botany and anatomy at the University of Jena, 200 km to the east of Göttingen. For his third wife Haller had thus abandoned his Heimat and his dialect for a girl thirteen years his junior from Saxony. The reader laughs – but such things really do matter.

Amalia was an efficient producer of mostly long-lived children, seven in all. Some suggest that the marriage was cold and loveless, but who knows? When eventually Haller took the girl from Saxony back to Berne with him, her life would certainly not have been easy, in just the same way that the Bernese women Mariane and Elisabeth had been uprooted from Berne to Hanoverian Göttingen.

To this day Haller specialists scratch their heads at the rapidity with which remarriage and procreation followed the death of Elisabeth. The engagement to the young Fräulein Teichmeyer took place scarcely three-quarters of a year after the death of Elisabeth and only a few months after the death of Elisabeth's son Johann Rudolf.

There is no explanation that is easily comprehensible to the modern mind, steeped as it is in the notion of romantic love. For the religious of the time, though, Christian teaching ordered the institution of marriage and the associated procreation of children as a sanctified state. The only alternative was celibacy – a cold and lonely state in every sense. Few people of that age spent time moping for a lost wife or husband. Haller was only thirty-three and had another thirty-six years ahead of him.

The final return to Berne

Haller remained in Göttingen until 1753. He had been there for around 17 years. They had been years of increasingly bitter, factional feuds, carried out against the background of Haller's declining health.

Haller returned to Berne in May 1753, a move which also causes, even today, the scratching of specialists' heads. Despite all the feuding, his reputation had grown steadily during his time at Göttingen. He now exchanged that position for a modest administrative role in the Berne Council. From now until his death he would be subjected to one political insult after another in Berne. His hopes of playing a significant political role there would be repeatedly dashed.

Albrecht von Haller (c.49) by Emanuel Handmann, Berne, 1757. Image ©Burgerbibliothek Berne.

Our concern is with Haller the poet and particularly his poem Doris, so what happened to him after around 1740, when he stopped writing serious poetry, is only of secondary interest.

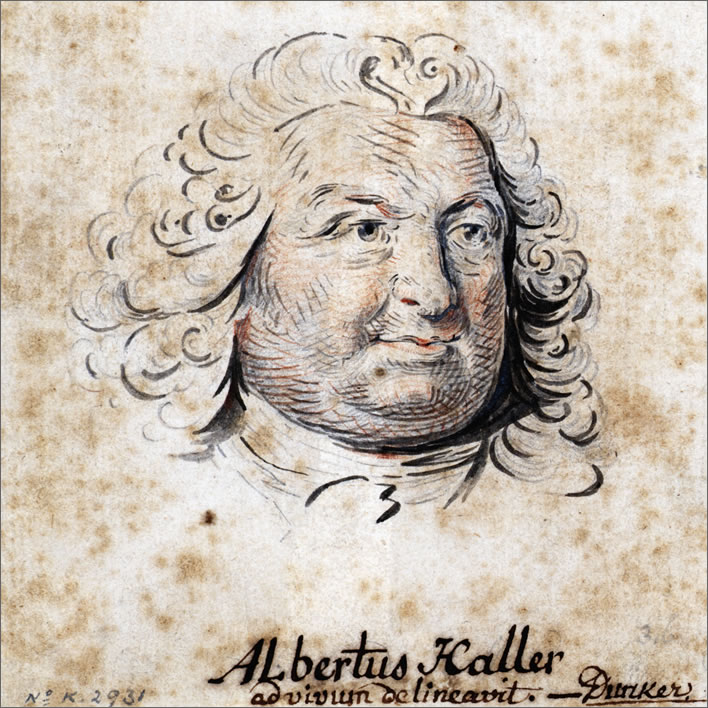

A sketch of Albrecht von Haller by Balthasar Anton Dunker, c. 1770, 'made from life'. The rapidity of its creation gives us faith in the accuracy of the representation of Haller, far from the black arts of the portrait painter. Image ©Private owner.

His time between his move to Berne in 1753 and his death in 1777 can be characterised as a great paradox: whereas his European fame expanded steadily, culminating on 25 November 1776 with the award of the Knighthood of the Polar Star by Sweden in 1776 and a visit by the Habsburg emperor Joseph II on 17 July 1777, his role in the Bernese swamp remained that of a middle-ranking bureaucrat, his foreign fame ignored or suspect.

Albrecht von Haller (c.65) by Sigmund Freudenberger, Berne, 1773. Freudenberg painted the picture as the model for an engraving for print use. Haller is seen wearing the cross of the Order of the Polar Star, a Swedish order of chivalry instituted in 1748 which was effectively the Nobel prize of its day. Haller received the honour in 1776 and had it painted onto Freudenberger's original. Image ©Private owner / Burgerbibliothek Berne.

He died on 12 December 1777, but the final insult from his Fatherland was yet to come.

He was buried in the churchyard of the 'French Church' in Berne (the church of the strongly Calvinist Hugenot exiles), but his grave was not marked with any permanence. At the end of the 18th century the cemetery was cleared and levelled: no one now knows where Haller's remains are. Nor had any one in Berne any interest in acquiring Haller's library or his papers: Emperor Joseph finally bought his library and parts of it ended up with Archduke Leopold in Tuscany; other works and manuscripts were scattered and some were lost.

The Bernese swamp that had so troubled and offended Haller was finally drained by the French and Napoleon. Quite a number of those in 'Switzerland' at the time were not unhappy at the Napoleonic stable-clearing that took place in many parts of Switzerland and which started the process that led to the foundation of the final Swiss Confederacy in 1848.

A conclusion – but not conclusive

Haller was a great man and a great poet. We may jib at his spiky personality, his self-destructive obsession with his Bernese Heimat and his rather eccentric and naive political ideas which were bizarre in his own time but which were rendered fatuous by the cataclysm of the French Revolution only a dozen years after his death. He was not the only one in that situation, though.

The word 'great' may be applied to him, but the word 'noble' is also apt. He lived a life of incessant labour and kept going despite all his setbacks: the loss of Mariane and Elisabeth; the loss of the children; his ill-health and suffering; his lack of recognition from those whom he really would have liked to recognise his contribution. There is also his absolute empirical honesty in his investigations, even in his drilling down into his every deed and motive. His setbacks were in scale with the greatness of his contributions: Ein hoher Baum fängt viel Wind, 'A tall tree catches a lot of wind' goes a German saying.

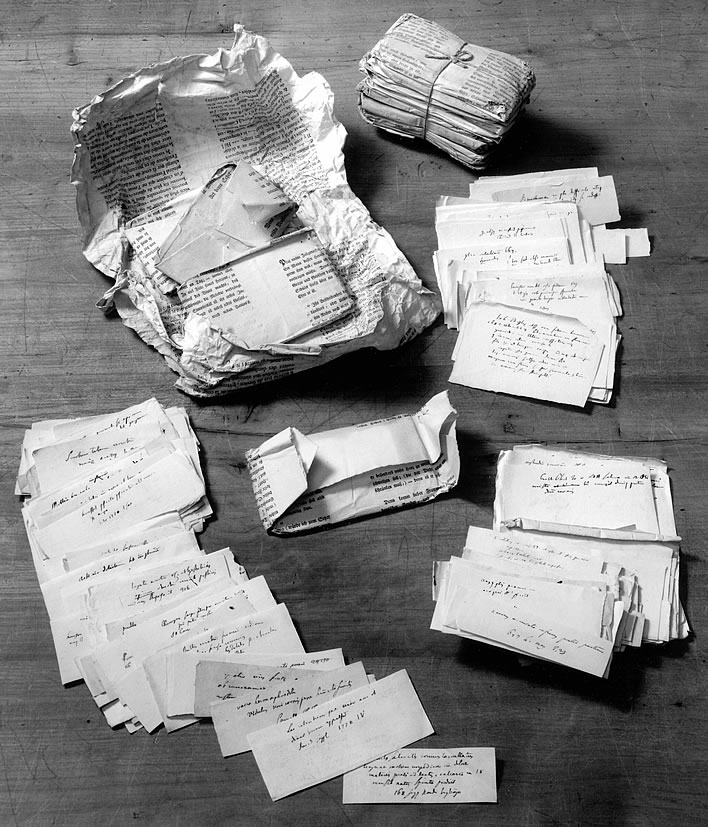

Top: Haller's collected scraps and notes found on his desk after his death.

Bottom: They are a reminder of a time before computers, databases, knowledge software and PostIt-notes.

Images: ©Burgerbibliothek Berne.

Funk's bust of him is the best portrait we have: lively, inquisitive, perhaps slightly tetchy, leaning forward, observing closely and critically. A great man in every respect. Despite all the sharp edges of his personality, Mariane Wyss knew exactly the quality of the man who was wooing her.

Photographs of a copy of a marble bust of Haller by Johann Friedrich Funk. The original bust is now lost. Images ©Burgerbibliothek Berne.

Choose your banknote Haller.

Top (series 7): the head and shoulders image of a vigorous, striving enquirer derived from Funk's bust of Haller, or, bottom (series 6): the head image of a blank-eyed, chubby nonentity loosely derived from Freudenberger's portrait.

The 'vigorous Haller' banknotes of the seventh series (top), designed by Roger and Elisabeth Pfund, were actually intended for use as the sixth series. However, the Swiss National Bank ultimately chose the designs by Ernst and Ursula Hiestand for the sixth series (bottom). The 500-franc 'vacant Haller' note of this series came into circulation in April 1977, was replaced in 1995 (when the 500-franc denomination ceased to exist) and finally recalled in 2000.

The Pfunds' designs were used for the seventh series, which was never issued and not made public. The seventh series was the 'secret reserve' that would be brought into circulation should there be massive counterfeiting of the sixth series notes.

Your penniless author had distressingly few opportunities to take a close look at the 500-franc, but, considering the impression the banknote portrait made on me, it is fair to say that the characterless image served Haller's memory badly for at least two decades.

The latest Swiss banknotes, the disheartening and brain-dead series 9 from 2016, contain no images of people at all. It would be quite impossible in the present cultural climate to find any historical figure who was not in some way morally defective. Haller's experiments on live animals would now certainly disqualify him from the modern pantheon, but since all the other plinths are now vacant he is in good company.

There was indeed a time (series 5, 1956) when the artist Pierre Gauchat could produce designs of great moral profundity for banknotes – the picture gallery of the people. No more.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!