Schubert's downward spiral, 1827

Richard Law, UTC 2018-09-17 11:18 Updated on UTC 2018-09-18

In 2012 the musicologist Rita Steblin carried out extensive and painstaking documentary research into the identity of a girl called Augusta ('Gusti') Grünwedel (1812-1855). [Steblin passim]

At first glance Gusti is of marginal interest to Schubert scholars. Her name is mentioned by the ever-scribbling von Hartmann brothers Friedrich ('Fritz') (1805-1850) and Franz (1808-1895) in their diary entries from the beginning of 1827. The reader is warned: we are going to deal with the Hartmann's diary entries in some depth: they are those diamonds in the dust of Schubert scholarship, contemporary records. Let us give thanks for the diarists in our midst!

The first ball, 10 February

Franz Hartmann's entry for 10 February 1827 is our starting point:

10 February 1827: Haas accompanied Fritz and me to Schober's apartment, where we had been invited to a ball. Present were all the Schober-Spaun male acquaintances and all the Schober-Schwind female acquaintances; namely twelve girls and young women, all of them at first unknown to me. All were very beautiful, apart from Netty Hönig, who is therefore more amiable, and Fräulein [Cäcilia] Rinna, who was also recently at [Karl von] Conci's.

Aus Franz v. Hartmanns Tagebuch:

10. Februar 1827: Haas begleitet Fritz und mich zu Schobers Wohnung, wo wir auf einen Ball geladen sind. Dort sind einmal alle Schobero-Spaunischen Bekannten männlichen und Schobero-Schwindischen Bekannten weiblichen Geschlechts; nämlich 12 Mädchen und junge Frauen, von denen ich anfangs keine einzige kenne. Alle sehr schön, außer Netty Hönig, die aber desto lieber ist, und Frl. Rinna, die auch neulich bei Conci war. [Dok 407]

This ball on 10 February was the first in a series held by the Schobers during the carnival season in 1827. They were held at the house Zum blauen Igel, into which the Schobers had moved shortly before.

For readers who are dipping a toe into the murky biographical waters that swirl around Schubert, Franz von Schober (1796-1882) was a member of the Freundeskreise, the 'Circles of Friends' that formed around the young composer – arguably the key member. He was a moneyed minor aristocrat with a colourful personality and a biography to match. He was almost the same age as Schubert, they met in 1815 and Schober soon become the dominant partner in a relationship that would last the thirteen years until Schubert's death in 1828.

Schober's inherited money allowed him to play a major role in the circles around Schubert as a sponsor of social events. This is the role in which we encounter him now. His importance for Schubert studies goes far beyond this limited role, however. We examined Schober in depth in our article Who is Schober? what is he? and we shall come back to him later in the present article.

The two tribes

Franz Hartmann's identification of the two tribes of friends creates a Venn diagram that overlaps at the figure of Franz Schober. It is an interesting and noteworthy representation of the situation. To the Hartmanns, firmly inside the Spaun circle, all the girls from the Schwind circle were unknown.

For the toe-dippers we should explain that 'Spaun' here refers to the civil servant Joseph von Spaun (1788-1865), who met the young schoolboy Schubert in the Vienna Stadtkonvikt, where Spaun was lodging during his university studies. He became a reliable friend of Schubert's, a friendship that lasted throughout Schubert's life. Spaun's memoir of Schubert is the most measured and extensive appraisal of the composer that we have.

His name is applied here to the Venn set representing to some extent the original members of the 'Circles of Friends' as well as members of the administrative and judicial classes of the Austrian Empire. The Hartmanns came from the latter group.

In contrast, the other Venn set is named 'Schwind', after the artist Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871). Schwind represents a group of younger people who got to know Schubert at the beginning of the 1820s, a second wave circle of friends as it were, who came in and substituted for the figures of the first wave, who had moved into jobs and marriages. In the early 1820s Schwind studied at the Vienna Academy of Art and brought his acquaintances from there into the Schubert ambit.

Given the differences in the backgrounds of the members between the two sets of the Venn diagram, it is not at all surprising that it took some time for the sets to blend into a whole: Franz mentions elsewhere in this diary entry that the first part of the ball was in fact quite awkward for some of the men, who had to cope with a room full of strange women talking amongst themselves.

Enter Fräulein Grünwedel

Back to Franz Hartmann at the ball…

The most attractive dancer was a certain Fräulein Grünwedel – [Joseph von] Spaun was completely enchanted by her. Wonderful, too, (actually the most beautiful) was the so called 'Flower of the Country' [Fräulein Louise Forstern]. We danced two cotillons, in which I had two very interesting partners: the famed pianist [Marie Leopoldine] Blahetka and Fräulein Grünwedel. [ …] Finally we sang and played music. […] The ball ended at a quarter past one.

Die lieblichste Tänzerin war eine gewisse Frl. Grünwedel, von der auch Spaun ganz bezaubert war. Herrlich war auch (und eigentlich die Schönste) die sogenannte Blume des Landes. Es wurden 2 Kotillons getanzt, wobei ich 2 sehr interessante Tänzerinnen bekam: die berühmte Klavierspielerin Blahetka und die Frl. Grünwedel. [...] Zuletzt wurde noch gesungen und musiziert. [...] Um 1¼ war der Ball aus. [Dok 407]

It is here that we first encounter a mention of Gusti Grünwedel in the Schubert documents. She emerges from nowhere into the Schwind circle. Out of the twelve women who were present she is one of the five women who are explicitly named: Hönig, Rinna, Grünwedel, Blahetka and Emilie [named subsequently].

Gusti was only fourteen at the time of this ball, so it should not surprise us that we find no significant documentary footprint for the previous life of such a young woman. Steblin, with great ingenuity, was able to track down the geneology of her early life, but of her character, interests and proficiencies at the time that she appears at this ball we know nothing – apart, that is, of her dancing skills and her charm, for which Franz Hartmann has singled her out here by name.

How did Gusti turn up at the Schobers' ball? Steblin makes a very plausible suggestion: Gusti's family had lived for around ten years (1809-1819) in St. Pölten. Schober's mother was the comforter of Bishop Johann von Dankesreithner (1750-1823), who became Bishop of St. Pölten in 1816. She spent considerable periods of time with him there.

In the small world of St. Pölten society it seems very likely that the Grünwedels and the Schobers had got to know each other there. Not only that, but both Schubert and Schober spent the autumn of 1821 wasting their time working on Schober's opera text Alfonso und Estrella, although by that time the Grünwedels had moved back to Vienna. It seems reasonable to assume, therefore, that Gusti was a friend of the Schober family, who 'came out', as it were, at the Schobers' carnival balls in 1827 when she was fourteen.

Franz Hartmann writes no special commendation of her beauty, but we sense from the context that she is somewhere near the top of the leader-board, at least. In modern terms, she would be a definite right-swipe on Tinder – but a SWAT team would be breaking down the door minutes later.

Her other claim on our attention is that she was apparently a great hit with Joseph von Spaun. Spaun was thirty-eight at the time, roughly ten years older than the Schubert-Schober generation. On 6 January of the following year he would become engaged in a good dynastic match to Franziska Roner Edle von Ehrenwert. They married on 14 April 1828, so we can put the upright and honorable Spaun's enchantment with the youthful Gusti Grünwedel down to the simple pleasures of the older man – these days a dangerous pastime.

Of the men at the ball, the diary entry mentions by name Schober, Schwind, Spaun, Fritz Hartmann and a major in the Hussars (text not reproduced here). There is no mention of the little, dumpy, thick-necked fella who took turns with Joseph von Gahy to hammer out the dance music all evening, most of which he had composed himself. He did not have the figure or the legs for a dancer and contented himself in the interludes with the beer and the sausages.

On this website we have often commented on Schubert's inescapable fate in the social circles around him of being the piano player banging out the dance music – even the events bearing his name, the Schubertiaden, may indeed have started off with some elevating Schubert songs, but they ended up with the Liederfürst, the 'Song Prince', having to hammer out the dances for the crowd.

We keep repeating this theme to counteract the bad habit of the many Schubert commentors who sentimentalise the exploitation of Schubert in these entertainments – as though the listeners and the dancers were doing Schubert some kind of favour. Eduard von Bauernfeld, however, that observer of men and manners, came into the circle late and kept his clear eye. He hit the nail on the head with his brief diary entry on a ball that took place the year before:

The day before yesterday a sausage ball at Schober's. Schubert had to play waltzes.

Vorgestern Würstelball bei Schober. Schubert mußte Walzer spielen. [Dok 343 Bauernfeld's diary, 16 January 1826]

Indoor games in Vienna

Back to Franz Hartmann at the ball. Despite the rather grim beginning of the ball for Hartmann, it ended magically for him:

I had to escort a girl [Fräulein Emilie], who lived near the Augarten, home all on my own. It was the most wonderful moonlit night and the air was very cool. My companion was very engaging and the long route seemed so short to me that I was unhappy when she arrived home. However, I was comforted, though, when we wished each other a very friendly good night and that the closeness of the farewell had been so enjoyable.

Ich mußte ein Fräulein, welches beim Augarten unten wohnt, ganz allein nach Hause geleiten. Es war die herrlichste Mondnacht, und die Luft strich äußerst frisch. Die zu Begleitende war sehr lieb, und die lange Strecke kam mir so kurz vor, daß ich sehr mißvergnügt war, als sie zu Hause anlangte. Indes ich tröstete mich, als wir uns recht freundlich guten Tag wünschten und das Herumstreichen gar so angenehm war. [Dok 407]

Readers who have experienced such moments of innocent romantic joy – may you be many! – will be happy for Franz Hartmann, that he could enjoy a brief spell away from the otherwise stifling social propriety of the ball.

The diary entry gives us an insight into the courting rituals of the Biedermeier period. These are relevant for us at the moment because they illustrate just what a complex and choreographed procedure was required in order to have any kind of emotional contact with the opposite sex. Even escorting was usually done in groups, hence Franz Hartmann's special pleasure at finding himself escorting an attractive and friendly girl otherwise unaccompanied.

We see how difficult it was to even get to know strangers at such a ball; the opportunities for socialising during the dancing were restricted; the escorted walk home at least offered some possibility of private conversation and even some light flirting.

Men alive now who were young in the 1950s, particularly those of us who went to single-sex schools, will be able to empathise with Franz Hartmann's frisson, a century and a half before, in the presence of a female, the mere touch of a hand and physical closeness despite half a dozen layers of winter clothes. Only fifty years later, the youngsters of the new millennium may need some effort and imagination for that empathy. They may find John Betjeman's poem Indoor Games near Newbury [Selected Poems 1948] a help.

Schubert did not have the figure for elegant dancing, nor the time: during the dancing he was usually busy playing the music; he might take a break and let Gahy take over for a while. The chances of Schubert the great introvert chatting up a busy dancer and popular honeypot such as Gusti Grünwedel must have been close to zero.

His interface opportunities with the opposite sex were not only limited in that way, but since he was staying with the Schobers – as Deutsch speculates – he had no cause to walk anyone home, even if he had had the build of a trusty cavalier. [Dok 408] He thus missed out on two of the main courting opportunities at the ball. No frisson for Schubert tonight!

The balls at Schober's are worthy of our interest because Franz's brother Fritz also reported on these notable evenings. For 10 February, Fritz has a slightly different view of the proceedings, a fact which actually reinforces, not reduces, the credibility of the Hartmann's accounts:

10 February 1827: At seven o'clock I went with Franz [Hartmann] to Schober's, following an invitation made quite a long time before, one which Josef von Spaun, who visited us this morning, repeated. Spaun collected us. At Schober's we met, among others, Spaun, Gahy, Enderes, Schubert, Schwind and his brother and Bauernfeld; and ladies who were almost unknown to me, e.g. Netty Honig, Fräulein Puffer, Leopoldine Blahetka (the famous young pianist), Fräulein Grünwedel etc. Most of the ladies were beautiful, which created a pretty picture.

Aus Fritz v. Hartmanns Tagebuch:

10. Februar 1827: Um 7 Uhr ging ich mit Franz zu Schober, einer schon lange vorher gemachten Einladung folgend, die Josef v. Spaun, der uns aufsuchte, diesen Vormittag wiederholt hatte. Spaun kam uns abholen. Bei Schober traf ich unter anderen Spaun, Gahy, Enderes, Schubert, Schwind und seinen Bruder, Bauernfeld; und Damen, die mir wenig bekannt waren, z. B. Netty Honig, Frl. Puffer, Leopoldine Blahetka (die berühmte junge Pianistin), Frl. Grünwedel usw. Die meisten der Damen waren schön, was ein sehr hübsches Bild gab. [Dok 408]

Whereas his brother Franz made little note of the men present at the ball, Fritz gives us a list, which even includes the piano players, Schubert and Gahy. We also get a specific mention of Fräulein Grünwedel, as one of those making up the 'pretty picture'.

However, the beginning was not so much fun since I had the misfortune to be paired with the single ugly girl among those present, a misfortune that I just had to bear. She was called Fräulein Rinna. I was luckier in the second cotillon: I danced with Fräulein Blahetka. Three years before she had delighted me, but since then she has lost a lot of her beauty and even more of her amiable behaviour, because in Germany, where she toured for 18 months, she received too much adulation. The music was wonderful, consisting as it did entirely of waltzes by Schubert, some performed by the composer himself, some played by Gahy. We stayed at Schober's until two in the morning.

Dennoch unterhielt ich mich anfangs nicht sehr gut, weil ich das Mißgeschick hatte, den ersten Kotillon mit dem einzigen häßlichen Mädchen unter den anwesenden zu tanzen, ein Mißgeschick, das ich notwendig ertragen mußte. Sie hieß Frl. Rinna. Beim zweiten Kotillon hatte ich mehr Glück: ich tanzte mit Frl. Blahetka. Vor drei Jahren hat sie mich entzückt, aber seit damals hat sie viel von ihrer Schönheit und noch mehr von ihrem liebenswürdigen Benehmen eingebüßt, weil man ihr in Deutschland, wo sie 18 Monate auf Reisen war, zu sehr gehuldigt hat. Die Musik war herrlich, da sie nur aus Walzern von Schubert bestand, zum Teil vom Komponisten selbst, zum Teil von Gahy gespielt. Wir blieben bei Schober bis 2 Uhr nachts. [Dok 408]

At least Fritz von Hartmann has not only, unlike his brother, mentioned the piano players by name but also given us an insight into the work they put into Schober's carnival ball. Finally we reach the escorting home phase of the evening:

At the end the men divided themselves up to escort the ladies. I accompanied Therese Puffer, with whom I now spoke more than at the entire ball, because I did not want to approach those girls who were occupied in talking to their friends. Finally, I accompanied the brothers Schwind to the Karolinentor.

Hierauf teilten sich die Herren in die Begleitung der Damen. Ich geleitete Therese Puffer, mit der ich bei dieser Gelegenheit mehr als auf dem ganzen Balle sprach, weil ich mich den Mädchen, die durch ihre guten Bekannten sehr in Anspruch genommen waren, nicht nähern wollte. Schließlich geleitete ich die beiden Brüder Schwind bis zum Karolinentor. [Dok 408]

The second ball, 17 February

The carnival season is traditionally a time of festivities before Ash Wednesday introduces the approximately forty days of solemn Lenten fasting leading up to Easter. In 1827 Ash Wednesday fell on 28 February, so the carnival period was now in full swing. The Schobers hosted balls on each of three Saturdays before Ash Wednesday: 10, 17, 24 February.

On 17 February, therefore, we hear from Franz Hartmann again:

17 February 1827: I got dressed at half-past six to go to the ball at Schober's. Almost the same people there as eight days ago; only not so many female dancers. Today Spaun was especially good humoured. Among the dancers the nicest was the so-called 'Young Nun', Betty Puffer, who is very pleasant. We danced vigorously. (I danced the two cotillons with Frau von Kriehuber and Fräulein Grünwedel.) In the breaks there was beer and sausages. August Schwind was also very friendly. I knew everyone much better than I had done eight days before. We all went home at a quarter-to three. I escorted Fräulein Hönig, but in the most unamusing way, since her aunt came with us.

Aus Franz v. Hartmanns Tagebuch:

17. Februar 1827: Um 6½ ziehe ich mich an, um zu Schober auf den Ball zu gehen. Es ist fast die selbe Gesellschaft da wie vor 8 Tagen; nur nicht so viele Tänzerinnen sind da. Besonders ist heute Spaun lieb. Mir ist unter den Tänzerinnen die liebste die sogenannte junge Nonne, Betty Puffer, die sehr angenehm ist. Wir tanzen tätig darauf los. (Ich die 2 Kotillons mit der Frau v. Kriehuber und Frl. Grünwedel.) In den Zwischenpausen gibt's Bier und Würsteln. Auch August Schwind ist sehr lieb. Ich bin schon besser mit allen bekannt als vor 8 Tagen. Um 2¾ geht alles nach Hause. Ich begleite die Hönigischen, aber auf die unlustigste Art, da ich eine Tante führen muß. [Dok 410]

Fräulein Grünwedel is mentioned by name on this occasion, too, and we note that Franz was even assigned to dance with her.

The third ball, 24 February

However the real high point came for Franz at the next ball, on 24 February, when another lucky opportunity to walk the beautiful Fräulein Emilie home came again. Brother Fritz, who left us no diary entry for the previous ball, was at this event, too.

24 February 1827: To the ball at Schober's where, in addition to the male and female dancers from previously (with the exception of Blahetka) there were the unpleasant Fräulein Rinna and a certain Marie Pinterics, who must be extremely beautiful and agreeable since most [of the men] are in love with her. I danced the first cotillon with the Young Nun, the second with the old aunt of Netty Hönig and the third with Fräulein Rinna. German dances with everyone. Fritz is unbearably boring. I break a cup. Dance terribly. Almost fall in love with the Flower of the Country. Escort, as 14 days ago, Fräulein Emilie home. Go back, ring at the main door about twenty times and stand there for more than three-quarters of an hour before it is opened.

Aus Franz v. Hartmanns Tagebuch:

24. Februar 1827: Auf den Ball bei Schober, wo außer den Tänzern und Tänzerinnen von neulich (ausgenommen Blahetka) noch die garstige Frl. Rinna und eine gewisse Marie Pinterics, die sehr schön und lieb sein muß, weil sich die meisten in sie verlieben, sind. Ich tanze den 1. Kotillon mit der jungen Nonne, den 2ten mit einer alten Tante der Hönigischen, den 3ten mit Frl. Rinna. Deutsche mit allen. Fritz ist unausstehlich langweilig. Ich zerbreche eine Tasse. Tanze übrigens entsetzlich. Verliebe mich beinahe in die Blume des Landes. Begleite, wie vor 14 Tagen, die Frl. Emilie nach Hause. Gehe zurück, läute am Haustor über 20mal und stehe da über ¾ Stunden, eh mir geöffnet wird. [Dok 410] [Dok 410]

We reproduce this here because of what it does not say – we wait in vain for any mention of the current focus of our interest, young Fräulein Grünwedel. She is also missing from Fritz's diary entry for this date. She was probably present at the ball, since Franz hints that the participants were much the same as at the previous ball, but if she was present she was not mentioned, if she was absent she was not missed. At this moment her name drops out of the contemporary Schubert documentary record, never to reappear.

Franz Hartmann's dotage

We are not completely finished with Gusti Grünwedel, however, because she appears in a chronicle written by Franz Hartmann in the 'evening of his life', as Deutsch puts it. [Erinn 318]Franz lived a long life for the times: he died in 1895, aged 87. Fritz had died long before, in 1850, 45 years old. Franz's memoir in his chronicle wraps his diary entries in an extra narrative, in which Gusti Grünwedel also plays a named part. Franz tells of her appearance at the first ball held by the Schobers on 10 February 1827.

On 10 February there was a particularly fine ball at Schober's, where Schubert played his 'Valses nobles'. Netty Hönig, the daughter of the advocate and Rector Magnificus Hönig (a flame of Schwinds, whose portrait he drew on the title page of Schubert's 'Suleika' and 'Geheimes'), Fräulein Puffer, Leopoldine Blahetka, piano virtuoso, Fräulein Grünwedel (the most beautiful one there in Fritz's opinion), a beautiful young Frau von Planer, Fräulein Rinna von Sarenbach, und Louise Förstern, sister-in-law of the lithographer Kriehuber, known as 'the Flower of the Land' (a beautiful blonde girl, whom I, after the ball, escorted home through a wonderful winter night far along the Taborstraße.

Am 10. Februar war ein besonders schöner Ball bei Schober, wo Schubert seine schönen 'Valses nobles' spielte. Es waren da Netty Hönig, die Tochter des Advokaten und Rector Magnificus Hönig (eine Flamme Schwinds, die auf dem Titelblatt von Schuberts 'Suleika' und 'Geheimes' gezeichnet), Fräulein Puffer, Leopoldine Blahetka, Klaviervirtuosin, Fräulein Grünwedel (Fritzen die Schönste), eine schöne junge Frau von Planer, Fräulein Rinna von Sarenbach, und Louise Förstern, Schwägerin des Lithographen Kriehuber, genannt 'die Blume des Landes' (ein schönes blondes Fräulein, das ich nach dem Balle in herrlicher Winternacht, weit in der Taborstraße, nach Hause begleitete). [Erinn 316]

He is relying on his diary entry, but has clearly not forgotten the romantic walk home with Fräulein Emilie nearly seventy years previously. However, at that distance in time her place in his thoughts has been taken by the 'Flower of the Land', Louise Förstern, the girl with whom he 'almost fell in love' at the third ball. A detail, true, but another warning to us always to take these Schubert memoirs made so long after the fact with some scepticism.

In this case the error seems to have arisen because in his diary entry for the ball on 10 February he did not give the name of the girl he escorted home that night. Her name only appears in an entry for the third ball fourteen days later. This omission left a gap which seems to have been filled by his defective memory and the memorably beautiful Louise Förstern, with whom would 'almost fall in love' at the third ball.

We are also puzzled by Franz's reference to Gusti Grünwedel, to the effect that she was in his brother Fritz's opinion the most beautiful girl there. There is no diary entry for Fritz which notes Gusti's special beauty; on the contrary, the only time that her name appears, at the first ball on 10 February, it is given in a quite factual way, with no further commentary. Fritz does not mention the second Schober ball which took place on 17 February at all and in his entry for the third ball, on 24 February, there is no mention of her either.

The impression she made on the Hartmanns was sufficient to get her a mention in their accounts and a footnote in history, but despite this, a week or two after surfacing in this interesting way, she disappears into oblivion – at least as far as the Schubert record is concerned. Despite the paucity of the original references, Rita Steblin was able to work out who she was and produce an impressively detailed account of her later life. Nothing in her later life has any significant connection with Schubert or the circles of friends around him.

Schober's dotage

If it were only this we would say 'very interesting' and move on. Except that Gusti was brought from being a mere footnote to being centre stage in the Schubert biography by an anecdote retailed by one of Schubert's closest intimates, Franz von Schober, on 10 June 1868 – that is, more than forty years after the fact. Schober didn't write this anecdote down by himself – that would have been too much like work – it was taken down in note form by the Viennese journalist, Ludwig August Frankl:

After the usual dance entertainment nearly everyone retired to the Kaffeehaus ' Zum Auge Gottes', 'The Eye of God'. Schober was suggesting to him [Schubert] that he should marry Gusti Grünwedel, a very charming middle-class girl (who later married a painter in Italy), who seemed to be well-inclined towards him. Schubert was in love with her, but he was 'bitterly modest', he was absolutely convinced that a woman could never love him. He jumped up while Schober was speaking, rushed off leaving his hat behind, incandescent with rage. After half an hour he came calmly back and explained later that he, beside himself, had walked around the St. Peter's Church saying to himself again and again that he would have no luck on earth.

Schubert went to pieces, he went into the redlight district, went on pub crawls, admittedly composing his most beautiful songs in them, as he also did in hospital ('The schöne Müllerin' according to Holzel's account), where he ended up through an excessively lecherous life and its consequences.

Nach der gewöhnlichen Tanz-Unterhaltung gingen fast alle ins Kaffeehaus 'Zum Auge Gottes'. Schober redete ihm [Schubert] zu, er möchte doch die Gusti Grünwedel, ein sehr anmutiges Bürgermädchen (die später einen Maler nach Italien heiratete), die ihm sehr geneigt schien, heiraten. Schubert war verliebt in sie, aber er war 'bitter bescheiden', er war der festen Überzeugung, ein Weib könne ihn nicht lieben. Er sprang bei den Worten Schobers auf, stürzte ohne Hut fort, zornglühend. Die Freunde sahen sich bestürzt an. Nach einer halben Stunde kam er ruhig wieder und erzählte später, wie er, außer sich, um die Peterskirche herumgelaufen sei und sich fort und fort gesagt habe, wie ihm kein Glück auf Erden beschert sei.

Schubert verwilderte, er lief vor die Linien, trieb sich in Kneipen herum, freilich auch in ihnen seine schönsten Lieder komponierend, wie er dies auch im Spitale tat ('Müllerlieder', nach Holzels Mitteilung), wohin er durch übermäßig wollüstigsinnliches Leben und dessen Folgen gelangte. [Erinn 304]

Putting aside the context to the tale, let us just look carefully at what Schober actually says.

The when and the where

Our first challenge in deconstructing Schober's memoir is trying to work out when the action described took place. It certainly did not follow on from any of the carnival balls at Schober's in February 1827. Each of the balls wound down in the early hours of the morning and was concluded with the ritual escorting home of the females. None of the males present is going to retire to a coffee house at three o'clock in the morning, especially after having walked a woman home.

From various other accounts we know that Schubert and Joseph von Spaun preferred not to hang around in coffee houses much beyond midnight anyway. [Dok 322 'Wenn Schubert dabei war, so war es für ihn ungewöhnlich, länger als bis Mitternacht zu bleiben.']

We must presume that by 'the usual dance entertainment' Schober meant one of the Schubertiaden, but he gives us no hint of which one it was. His very use of the expression 'the usual dance entertainment' – not a circumlocution we might expect from the hand of Frankl – is troubling. Schober was, after all, the person who coined the termSchubertiade for marketing purposes. It is odd to find that he writes merely of a 'dance entertainment'. Schubert participated in dances, balls, parties and Schubertiaden– there is nothing in his life that corresponds to 'the usual dance entertainment'.

The phrase is really quite demeaning – no mention of wonderful songs or piano music – and thus quite in keeping with the Schober's intent in all his reminiscences of Schubert to denigrate the little composer as a helpless half-wit. The present anecdote is no different.

The Eye of God

Schober's confident assertion that the meeting took place in the coffee house Zum Auge Gottes is dismissed out of hand by Deutsch, who helpfully suggests one or two of the known coffee houses frequented by the Schubert crowd, nor does that establishment figure in any of the Schubert-relevant coffee houses listed in Rudolf Klein's helpful Schubertstätten. [Klein 133]. Deutsche's improvements to Schober's defective memory do not impress us. The fact is that Schober confidently names a wildly improbable location for his anecdote and in so doing serves up yet one more piece of nonsense which we have to discount.

In Schubert's time the inn Zum Auge Gottes was a well-known travellers' hotel and restaurant just outside the fortifications, the Linienwall (or simply the Linien), which enclosed the city of Vienna and its immediate suburbs, the Vorstädten. These fortifications were pierced by a number of gates (between nine and fifteen, depending on the period). In this particular case the boundary gate in the Nußdorfer Linie was where the Nußdorferstraße became the Döblinger Hauptstraße. [Winterstein passim]

Zum Auge Gottes was located just outside the city limits. It offered inexpensive accommodation for travellers and bargemen using the nearby Donaukanal, the Danube Canal; for the inhabitants of the city it was also a staging post to the wine gardens, the Heurigen, in the outer suburbs. There was even a customs house located at what is now Nußdorferstraße 90.

In short, Zum Auge Gottes was a place that was well known to most Viennese and would have been particularly well known to Schubert, since the Schubert stamping grounds Himmelpfortgrund, Lichtental and Rossau are all near neighbours.

There is another connection to Schubert: through the inn's proximity to the Währinger Ortsfriedhof, the Währing Cemetery, it was popular as the place to which those remaining above ground would retire for the wake, the Leichenschmaus. That is the cemetery in which Franz Schubert ended up 190 years ago and where he remained until the second exhumation in 1888. Realising that they had a now famous tourist attraction on their hands, the Viennese put him in a grave of honour in the Zentralfriedhof.

I have never seen any mention of a Leichenschmaus for Schubert – perhaps he was too poor to pay for one. If so, it's a pity: a good Leiche was and still is a Viennese cultural tradition.

There is now no trace of the inn that Schubert and his friends would have known: in an uprising in Vienna during the revolution year of 1848 it was plundered and damaged – some say completely destroyed – sold, rebuilt several times in slightly different locations and finally obliterated in the course of the city development of Vienna in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

A scene at the Nußdorfer Linie on 23 October 1848 (170 years ago next month). The tree-lined road in the background leads to Döbling; the Auge Gottes is the blazing building next to the road. Image: Bezirksmuseum Alsergrund in [Winterstein 5]

Although everything so far written here about Zum Auge Gottes might be taken to reinforce Schober's account, there are two insurmountable problems: firstly, the inn was certainly not the place to which the Schubertians would retire after a Schubertiade– it was simply too far out of the way; secondly, the inn is about 3 km from St. Peter's Church as the crow flies, meaning that to go from the inn to the church, do a circuit or two and then return to the inn, all within half an hour, would require a performance from our portly composer worthy of a modern Olympian, with or without his hat.

The Eye of God, revisited

Well that was all very interesting, wasn't it?

Unfortunately, although what I wrote about Zum Auge Gottes near the Nußdorfer Linie is correct in itself, it is almost certainly not the Aug Gottes referred to by Schober.

Dr Steblin writes to remonstrate politely with me: Why didn't I check 'Behsel '? (the indispensable Viennese house register from 1829). Anton Behsel lists two Aug Gottes in the vicinity of St. Peter's. Hmm… The politeness is the most wounding part about it.

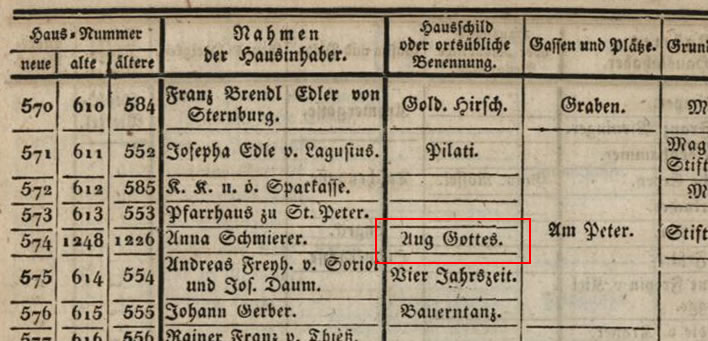

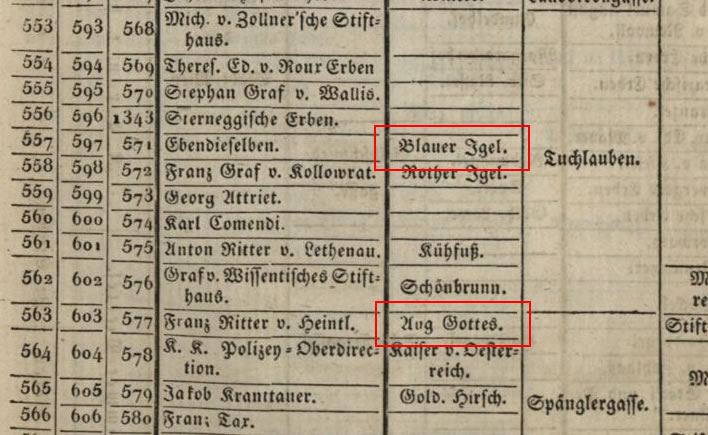

Why didn't I check Behsel, indeed? After the carnival trebles all round for my brilliant detective work at the Nußdorfer Linie it is the sackcloth and ashes of Lent for me now. Here, for example:

The entry in Behsel for the Aug Gottes on St. Peter's Square. Image: Wienbibliothek.

The entry in Behsel for the Aug Gottes in the Spänglergasse, as well as the Schobers' apartment in Tuchlauben. Image: Wienbibliothek.

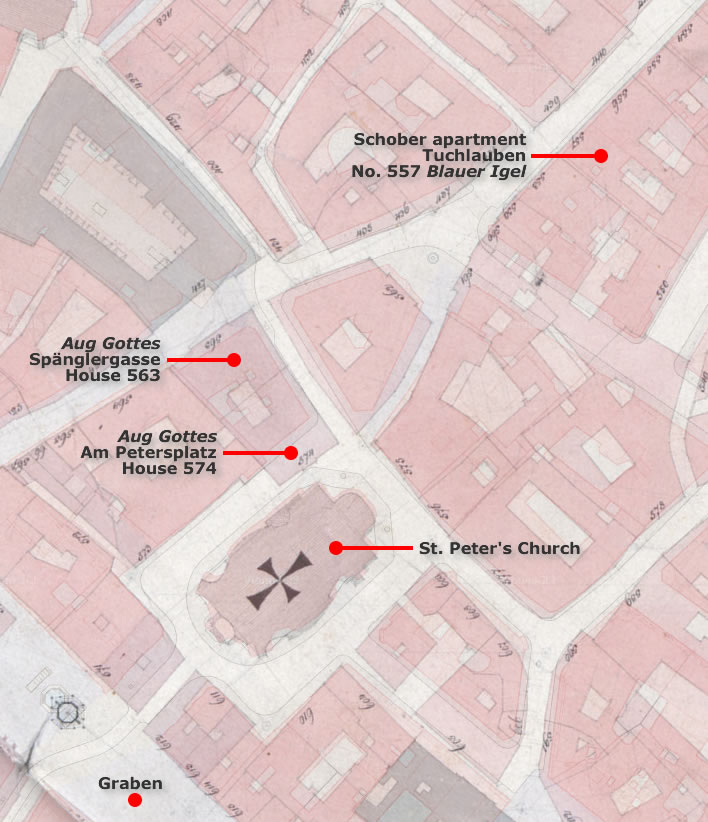

On the Behsel map we can see the spatial relationships between the two Aug Gottes, St. Peter's Square and the Schober family's apartment. The two occurrences of the name Aug Gottes seem to apply to the same building; the side facing the square may have housed the coffee house. If it did, it would be a very convenient gathering place after a dance or a Schubertiade at Schober's apartment. Image: ©ViennaGIS / Wien Kulturgut.

Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa. Perhaps my visceral dislike of Franz von Schober led me astray.

Marriage in accordance with his station

Schober's portrayal of his prompting Schubert to marry Gusti Grünwedel is unconvincing. His assertion that Schubert was 'in love with her' is backed up by no other source. Our harsh scepticism on this point is justified: everything else he has told us so far has been demonstrably false and so we have to treat this statement as being the issue of a confused mind.

The anecdote is worse than unconvincing, in fact it is really quite cruel – as we would expect from the unpleasant Schober.

This is the man who drew the cruel caricature of the little pot-bellied Schubert following in the wake of the magnificent Michael Vogl. Schober, a man supposed to be the devoted Schubert's soulmate – only a bully exercising social power could be so hurtful to an acolyte. Schober hoarded that illustration carefully in his archive. We don't know whether Schubert himself or any of the circle saw this hateful caricature. By their words and their deeds shall ye know them.

Schober's caricature of Schubert and Vogl 'setting out to battle and victory'.

Schober now presents us with a scene in which the socially inadequate little composer is being encouraged to attempt to obtain the hand of the Bürgermädchen, the explicitly 'middle-class girl' – a women suitable to his low status.

The translation 'middle-class' for Bürgermädchen is unavoidable, but very misleading. In contemporary English 'middle-class' is code for solid respectability, usually meant positively (unless, of course, you are the author of the Harry Potter books).

In contrast, at Schober's time and in Schober's mouth Bürgermädchen suggests a girl with socially questionable origins, one who may or may not be a fine girl, but who could never hope to marry into aristocracy. We remember that other fine Bürgermädchen, Therese Grob, allegedly Schubert's first love. She married within the artisan class – a master baker – and went on to live a successful and comfortable life.

The elevated ladies who came to the Schubertiaden were not for the likes of Schubert, clearly.

Franz von Schober could never acknowledge that Schubert was in so many ways his superior; he could only take refuge in his own inherited money and his inherited title. The scene Schober presents of the shy composer being chivvied by him to pluck up courage to ask a common girl to marry him is sickeningly demeaning. Was this attainable 'love' Schober's answer to Schubert's 'love' for the unreachable Caroline Esterházy? How shall we ever know?

Nearly everyone saw, no one told

The main action of Schober's anecdote is that Schubert rushed out without his hat, walked around the church for half an hour, then returned to tell everyone his problem. The forgotten hat is the sort of prop that good conmen use to add some reality to their tales (as was the name of the coffee house). Did no one go after the distressed composer? – with or without his hat? Do we really believe that the group sat around for half an hour as though nothing had happened?

We have no idea either to whom Schober's phrase 'nearly everyone' refers. The membership of the Schubert circles was in flux for most of the 1820s and since we have not the slightest indication of the date of these events we shall never be any wiser in this respect.

Search as we may, we can find no corroborating account of the remarkable event described in Schober's anecdote. Amongst the gathering of friends in the coffee house after an evening's partying there are multiple potential witnesses to this astonishing behaviour of Schubert's, yet not a hint of it finds its way into any diary or letter that we have. From 1826 onwards the Hartmann brothers are scribbling assiduously in their parallel diaries, yet there is no report of this remarkable incident, not even via gossip from others. Bauernfeld? – nothing; Schwind? – nothing; the Spauns? the Hartmanns? – nothing. Let us not forget: 'nearly everyone' was there.

Why Gusti?

And why does Schober explicitly name Gusti Grünwedel of all people? Doesn't this have a ring of truth about it?

No. Just think of it: on the one hand we have a pretty fourteen year old in 1827, a fine dancer, adored by a Spaun, one of the most beautiful and feted girls in the room. On the other we have Schubert, the tubby little composer, syphilitic, thirty, bespectacled, who couldn't even dance properly.

Of course Schober had no idea about the Hartmanns' diaries and thus had no idea that his fantasies would be competing with contemporaneous documentary evidence. Without them he would be our only authority on Gusti Grünwedel.

It's a fine Schober joke, to have the great composer aim for and fail to win one of the prettiest girls in the room. When we consider the talents of Caroline Esterházy, whom Schubert quite credibly adored and who quite credibly venerated him, do we really think that Franz Schubert, thirty, lost his heart to a 14-year-old know-nothing? Schubert in love?

Scarcely ten years before Gusti appeared, the 19-year-old Schubert wrote an aphorism in his diary that answers our questions:

Happy the man who finds a true friend. Happier the man who finds a true friend in his wife.

Glücklich, der einen wahren Freund findet. Glücklicher, der in seinem Weibe eine Wahre Freundinn findet. [Dok 49, Schuberts Tagebuch, 8 September 1816.]

Well, we all write down strange things when we are teenagers, but the direction of this particular teenager's thought is quite clear: his search is not merely for sex or a dynastic connection, but for someone who understands him.

We Schober-haters might imagine, in fact, that of all those present, juicy little Gusti would be the girl on whom the voracious Schober, the man of the world, would set his sights, the youngster powerless at the gaze of Mephisto and the sound of his mellifluous voice.

Schober reveals his closeness to Gusti by the throwaway information – albeit incorrect – about her later marriage. Thanks to Steblin we know that this took place in Vienna on 13 November 1831 to a medical doctor, Peter Stoffella; Gusti was nineteen by then. Schober may be wrong in these details just as all his other details, but we can conclude at least from the fact that he names her of all people, that he had been paying attention to Gusti, the girl from the Schober-Schwind circle. Her pretty image seems to have been still haunting the 72-year-old's jumbled imagination.

Of course, if Rita Steblin's reasonable suggestion that the Schober and the Grünwedel families knew each other from St. Pölten is correct, Schober would have a reason to remember her in particular and her later destiny, meaning that our lascivious aspersions may be superfluous. But in this case he would also have had a reason to mention his family's connection with her, which, however, he fails to do. Was he playing at being the matchmaker intermediary between Schubert and the friend of the family? Who knows?

It is possible that Schober called up Gusti from the depths of his memory as an example of the first 'middle-class' girl he could think of. It is, of course, completely speculative to imagine Schober flirting with little Gusti, admittedly, but not unreasonably so; but to imagine Schubert doing that is absurd. Here is what we wrote about Schober in the period after Schubert's death:

At the beginning of 1830 he became the companion/secretary of Leo, Count Festetics (1800-1884) in Budapest – 'Pest' at that time – and a governor to his children. The terms of Schober's employment were generous in both time and money. Schober, a restless traveller, kept a foot in Vienna, too. His mother died on 23 March 1833 and there followed a bitter inheritance battle with his uncle. Up until the 1840s his time in Vienna was marked by a number of affairs. He finally gave up his apartment in Vienna and continued with his travelling. We hear of him in Rome, Naples, Sicily, Florence and Paris.

Schubert goes off the rails

Schober is a textbook case of psychological projection, that is, attributing those faults that are within him to someone else. As is often the case with those who possess social power, Schober was an intuitive manipulator of truth. He tells us of Schubert's despairing descent into libertinage after the Gusti debacle, tut-tutting, more in sorrow than in anger, affecting the moral high ground of a country parson.

Schober? we say… Schober?!

Readers of our piece on Schubert's syphilis infection may remember the judgement of a real moralist, Vienna's first magistrate, Josef Kenner, on Schober. He was 'the false prophet who uttered the euphemistic words of sensuality' and whose 'demonic lure of the association with that superficially warm but internally merely vain being' ruined those who had no resistance to him. Hard words, but quite just.

From his befuddled brain Schober even seems to be hinting to us that Schubert's syphilis arose during this period and led ultimately to his death a year later. His formulation of this is a classic piece of Schober rhetoric in which he has turned history on its head:

- Schubert fails to propose to Gusti (1827?);

- leads lecherous life, spiralling downwards to depravity;

- Schubert goes to pieces, catches syphilis (1823), writes Die schöne Müllerin in hospital (1823)

In this timeline, according to Schober's anecdote, the passion for Gusti has to come before Schubert's derailment, which would make Gusti about eight years old. It doesn't work: Schober has got Schubert's biography and Gusti's role in it the wrong way round. We realise now – if we hadn't realised it earlier – the extent of Schober's derangement. But, nota bene, it is a functional derangement, intended for the greater glory of Schober: if only the ineffectual Schubert had taken Schober's advice and married the Gusti girl, how different his life would have been!

We should therefore dismiss Schober's account of the despairing Schubert out of hand – not even a glimmer of it is credible. It is so jumbled that we might even begin to believe that Schober's brain was finally being destroyed by the neurological effects of stage four syphilis, since it is occasionally suggested that Schober picked up an infection at the same time as Schubert, were it not for the artful malignity of the anecdote.

No. Enough. Purge Schober's nonsense from our minds and together with it the ghosts and fantasies of the 'heartbroken Schubert'. Once that is done, our view of Schubert in 1827 can be brought into clearer focus and Gusti Grünwedel returns to being a couple of quaint asides in the Hartmanns' diaries and chronicle. There is then no evidence for an association between Schubert and Gusti.

Schubert's certificate of baptism

Well, so far we have found the diary entries of the Hartmanns' to be extremely reliable documentary accounts; the very late memoir by Franz Hartmann, despite being based on a contemporaneous diary, has some blemishes; Schober's late memoir of the the Gusti Grünwedel episode and Schubert's moral decline seems to contain no detectable truth whatsoever.

There is, however, a troublesome fact that remains inexplicable. On 3 January 1827 Schubert appears to have ordered a copy of his baptismal certificate. Otto Deutsch tells us this, relying on Kreissle. He also confesses that he has no idea why this baptismal certificate was needed at that time.[Dok 397]

Steblin takes the existence of the certificate to be 'a sure sign that he was thinking of getting married at this time.' [Steblin 81] Baptismal certificates were required to prove the ages of the bridal pair. If either was under twenty-four he or she needed the written approval of the respective parent. Steblin's conclusion seems unavoidable: why else would Schubert need a copy of his baptismal certificate other than in contemplation of marriage?

In such tricky situations our first thought would be to look carefully at this copy of the baptismal certificate. The trouble is, we can't. The document is – go on, have a guess – that's right: 'lost', so we are unable to verify its authenticity or its contents.

Kreissle relies on the information in this copy to provide the baptismal record for Schubert; he does not use the original record in the baptismal book of the parish of Lichtenthal.

The transcription of the copy that he gives us is correct in every respect when compared with the original baptismal entry – except for the one thing we now cannot double check: The date it was issued: 3. Jänner 1827.

We therefore have no option but to rely on a chain, the first link of which is the clerk who made the copy and dated it 3 January 1827, the second link is Kreissle's transcription of that date and the third link is the accuracy of the printer who set the transcription in a footnote. We now have to take the eyesight, handwriting and work of all these people on trust.

All our documentary woes rest on the apex of this upside down pyramid. For example, if during one or other of the transcriptions in this chain someone wrote '1827' instead of '1817', this one character difference would mean that we now ought to be writing about Therese Grob, Schubert's alleged lost love from that time, rather than Gusti Grünwedel, Schubert's alleged lost love from ten years later. Had the '7' in '1827' really been a '1' – an easy error to make – we would now be hunting for a different secret love of Schubert's. In either case the pyramid would topple over and the hunt for the 1827 engagement would cease.

It is a bit of a surprise that Kreissle would let a copy of a baptism record made at such an odd moment in Schubert's life pass through his hands without questioning the reason for its existence at that date. Ah, well … nobody's perfect.

Onwards. Let us assume that the pyramid hasn't toppled over and that Schubert really did order a copy of his certificate of baptism on 3 January 1827. What on earth for? In the current state of our knowledge about Schubert this act makes no sense at all.

The would-be groom

Steblin, taking Schober's coffee house tale at face value, suggests that this moment, coupled with the carnival balls in February, may have been the time when Schubert proposed to Gusti Grünwedel. The only trouble with this idea is that it leaves us with the problem of why Schubert should order this document before he even proposed.

Schober's anecdote says in essence that Schubert could not even bring himself to propose. If we believe that, why would Schubert order the paperwork that he would only need around the time of his wedding day, before he had even proposed to Gusti? The sequence is clearly wrong.

In the normal course of events he would have had to propose to Gusti before he ordered the copy of the certificate. Since she only turned fourteen on 1 September 1826, Schubert seems to have been coming out of the blocks extremely quickly in her case.

We would assume that Schubert and Gusti had known each other for a while before 3 January 1827. Of this romance we hear nothing at all. In fact, the Hartmanns' accounts of those balls clearly imply that Gusti is a newcomer – at least to them and the rest of the Spaun circle, even to Joseph von Spaun himself, since Franz Hartmann's description of Spaun's delight in the young lady at the first ball suggests that it must have been the very first time that Spaun had met Gusti. It is stretching our credibility that Schubert had been consorting with Gusti for at least a few months without Spaun or anyone in the close circle finding out about it. This seems to be yet another reason for us to discount any kind of courtship between Schubert and Fräulein Grünwedel.

Schubert was living with the Schobers in 1826 and – after a brief gap – in 1827. If Gusti were a friend of the Schober family it would seem reasonable that Schubert encountered her at some time while he was under the Schobers' roof. But we are once more confronted with the inescapable fact that before 1 September 1826, Gusti was under fourteen years old.

Let us discount Schober's nonsensical anecdote about encouraging Schubert to marry Gusti and take her completely out of the situation.

In which case, following the normal order of things, the existence of the copy of the certificate of baptism dated 3 January 1827 would mean that Schubert had proposed to someone sometime towards the end of 1826 and been accepted. At the beginning of January we find him therefore assembling the documents he needs to get married in the Austrian Empire of Paperwork.

The whole affair must have been undertaken in complete secrecy, for we have no contemporary record about it from anyone. Then, at some point after he had obtained the certificate, the marriage project must have ended. Why?

Unfit to marry

One of the obvious causes for such a rupture might be the Ehe-Consens-Gesetz, the 'Marriage Consent Law'. It was also Rita Steblin who drew our attention to the malign effect of this piece of Habsburg administrative nonsense and pointed out the way it almost certainly affected Schubert around 1816.

The law came into effect in 1815 and remained in effect until well after Schubert's death. The intention was to ensure that families were financially secure and thus morally sound, but all it did was ensure that the poor had no hope of an orderly married and family life.

In essence it forced the lower orders of society to obtain permission to marry. The great, the good and the civil servants were unaffected, but those squashed underneath the feudal structure of the Austrian Empire had to prove that they could support a wife and family. The law was particularly aimed at the class of wandering artisans and apprentices (for example, the disappointed chap in Die schöne Müllerin). Composer Schubert can be regarded as collateral damage. The reason we hear so little of this vicious law is that it only affected the underlings, the common people about whom we read so little in the traditional histories.

There was no escape for Schubert from this terrible piece of legislation. In order to marry, he would have to prove he had sufficient wealth to support a family. It is true that he didn't have to guarantee future income – how could anyone do that in such uncertain times? – but how could Schubert, the freelancing genius, demonstrate his earnings? His situation in 1827 was little different to his situation ten years before in 1816. In 1827 he was at least earning money, but irregularly and without hope of reliably supporting a wife and family.

We note in passing another aspect of Schubert's outsider role in his circle that might have caused him some depression: he was probably the only one of those around him to whom this law applied.

That Schubert himself even seems to have contemplated such a step in his financial circumstances strikes us as odd – just one more thing we don't understand in his biography. Even without the malign shadow of the Ehe-Consens-Gesetz, how on earth could Schubert afford to marry anyone?

But how could this situation have changed in such a way that Schubert was motivated to request a copy of a baptismal certificate? It must have been clear to him from the outset that there was no chance that he would get permission even before he sent off for the baptismal certificate.

Unless, of course, his putative wife was so rich that he did not need to provide support for her or any children that might appear. It would not have been the first morganatic marriage in history. Now, there's a thought. I wonder who the lucky girl was going to be? …

Sources

All translations ©FoS.

| Dok | Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Dokumente Seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. [DE] |

| Erinn | —, ed. Schubert: Die Erinnerungen Seiner Freunde. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1997. [DE] |

| Steblin | Steblin, Rita. 'Schubert's Unhappy Love for Gusti Grünwedel in Early 1827 and the Connection to Winterreise. Her Identity Revealed' in Schubert: Perspektiven Band 12, Heft 1, 2012, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart. [EN] |

| Klein | Klein, Rudolf. Schubertstätten, Wien, Lafite, 1972. [DE] |

| Winterstein | Winterstein, Stefan. 'Das "Auge Gottes"' in Mitteilungsblatt des Bezirksmuseums Alsergrund, 43. Jahrgang, 168, Juni 2002, ISSN 0017-9809. PDF-Download [DE] |

Update 18.09.2018

Some typos corrected.

Dr Steblin emails me, kindly elucidating my errors. Oy Vey! I switch my monitor off. Out of the darkness the shade of a long-dead teacher approaches. He must have been down below, probably with Schober, the pair of them laughing at my current discomfort.

- My judgement was sound, boy, all those years ago, wasn't it?

- Yes, Sir. Completely.

- Now take a hundred lines: 'I must not jump to unwarranted conclusions' – and make sure you spell 'unwarranted' correctly this time. Stupid boy.

- Yes, Sir.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!