Schober after Schubert

Richard Law, UTC 2016-12-09 06:49

Finale

It requires no effort to imagine the shock of the friends at Schubert's sudden and completely unexpected death on 19 November. Bauernfeld wrote in his diary the day after:

Schubert died yesterday afternoon. Monday I was speaking to him. Tuesday he was in a delirium. Wednesday he was dead. He talked to me about our opera. It is just like a dream for me. The most honest soul, the truest friend! If only it were me lying there and not him. However, he departs the Earth in glory!

Deutsch Dokumente p. 549f.

Schubert's death came at a very bad time for Schober: his business was on its last legs and bleeding money. In this context we now understand why Schober's outstanding loan to Schubert of nearly 200 Gulden was paid back so promptly by Schubert's family after his death – Schober needed the money. We think back to the objections that were put into the mouth of Schubert's father by Schober when, in 1815, Prince Charming Schober rescued Cinders Schubert from his domestic drudgery, giving him food, lodging and money. Thirteen years later Father Schubert and brother Ferdinand drew up the final accounts on Schubert's life and find that Cinders was still in debt to Prince Charming. Thirteen years and still in debt! and to him, too! What must have been going through Father Schubert's mind?

Other friends took up the task of organizing Schubert's obsequies. Schober tells us much later via Schubert's biographer Kreißle that the family made him, as Schubert's 'closest friend', the principal mourner in the funeral cortege. For the burial service Schober adapted his text from 1817 for Schubert's Pax Vobiscum [D 551]. As far as doing anything more was concerned, he told one of the circle of friends, Johann Baptist Jenger (1797-1856), that 'his present circumstances did not allow him to take a leading role' either in the organization of a requiem or in an appeal for a monument. Given Schober's lack of administrative skills that was probably just as well.

At Jenger's bidding Schober produced a lithographed invitation to Schubert's Requiem Mass on 23 December and a leaflet appealing for subscriptions to the cost of a fitting monument for the dead composer. The campaign for funds for a monument was supported by two concerts organized by Anna Fröhlich on 30 January and 5 March 1829. Schober did not print the leaflets for these concerts nor did he subscribe to the rapidly confected Schubert 'song cycle' Schwanengesang [D 957]. By that time his business had collapsed completely and was in the process of being sold. A substantial portion of his assets had gone with it.

Summa summarum: Schubert was dead and buried, some obituaries were written, his monument was built and his memory faded.

Coda

The estimable and heroically workaholic Schubert scholar Otto Erich Deutsch tells us that three obituaries of Schubert appeared at the end of 1828. They are short, generous and reverential and do exactly what obituaries are supposed to do. In February of the following year Johann Mayrhofer published a touching personal recollection of Schubert. About the same time, Anton Ottenwalt wrote to Joseph von Spaun with some of his own recollections and encouraged Spaun, as one having a greater gift for the task of describing Schubert's life, to attempt a fitting tribute.

Spaun wrote to Bauernfeld suggesting a meeting with Schober in which the three of them could list all the points from their memory of Schubert. That would have been be the rational, educated, civil-servant's way of doing things, but the meeting never took place – a missed opportunity that was a disaster for Schubert scholarship. It seems reasonable to assume that the fault for this lay on Schober's side: Both Spaun and Bauernfeld were diligent by nature and wrote their own pieces about Schubert, whereas Schober, by nature indolent, was now additionally beset by apathy and torpor after the catastrophe of his business venture. He never wrote anything. He later claimed to have done so and given the work to someone, but if he did, the work has never been found.

But all that aside: Schober's personality ruled out his participation in the construction of a shared historical narrative. Schober needed to construct his own narrative in order to fulfil his craving for Geltung, 'importance' or 'recognition'. Schober could never share a common, relatively objective biography – there were too many things he needed to add and too many to hide.

Bauernfeld's substantial and beautifully written piece appeared in three parts in the Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst etc. the 'Viennese Journal of Art etc.' at the beginning of June 1829. In other words, Bauernfeld delivered an encomium to Schubert promptly, whilst the memory of the composer was still alive.

Spaun, too, wrote a long and detailed memoir, also very well crafted. He sent this to Bauernfeld, who we know used some of it in his own piece. For whatever reasons Spaun's memoir was not published at the time. A manuscript copy of the original found its way into Schober's archive and then into the hands of a Berlin collector of Schubertiana. Lacking any normal attribution, he designated it as the work of Schober. Perhaps this is what Schober had intended all along. We have to ask, what sort of person archives a laboriously made copy of a text without adding the author's name to it? It was 1936 before Spaun's text was finally published, correctly attributed.

We know that Ferdinand Schubert (1794-1859) wrote a memoir of his dead brother as early as 1828. Ottenwalt and Spaun seem to have seen it, but Ferdinand's pedestrian, teacher's prose did not impress. It was never published. The composer and virtuoso Robert Schumann (1810-1856) visited Vienna in the winter of 1838/9 and as part of his attempt to rescue Schubert's musical legacy it seems likely that he encouraged Ferdinand to rework and publish his original essay. This appeared in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik in Leipzig in spring 1839, just over ten years after Schubert's death. In those ten years Ferdinand's prose style had not improved.

It took nearly 40 years for Schubert's life to be given a biographical treatment. We wrote of the metaphorical tunnel into which the memory of Schubert disappeared after the obsequies and the obituaries were over. That tunnel ended around 1857, when the Austrian musicologist Ferdinand Luib wrote to Schubert's friends asking for their memories of the composer. Luib never completed his biography and passed on his materials to Heinrich Kreißle von Hellborn, who brought out the first biography of Schubert in 1865.

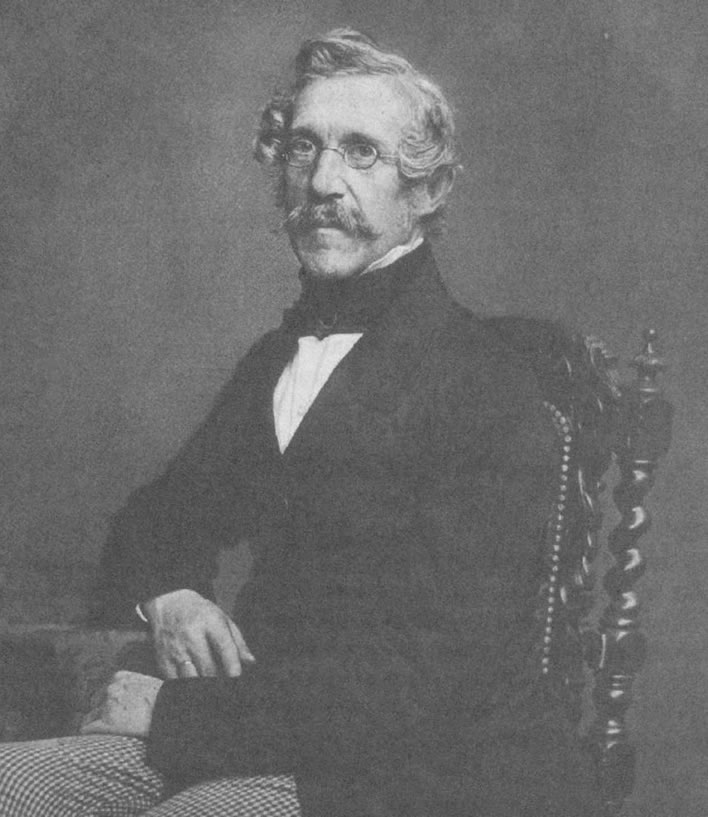

Joseph Danhauser, Franz von Schober, 1844

1865 was the year of Josef von Spaun's death. Moritz von Schwind would last until 1871, Schober until 1882 and Bauernfeld until 1890. As far as we know, Schober did not respond to Luib. His contributions to all subsequent biographical works are at best self-serving, at worst quite malign. As an example of self inflation combined with avoidance of effort we only have to look at an undated letter of Schober's to Kreißle:

In the small library that I set up for him Schubert found a copy of Müller's 'Winterreise'. He was attracted to these songs and set them, as with so many other poems, in his characteristic, musically lyrical style.

In everyday life only a few had the opportunity, in rare moments, to appreciate what a noble soul was in him. These people saw this in gestures and words, which are not easy to repeat and describe.

Deutsch Erinnerungen p. 235.

Schober's attempts to reshape history, his objections to the biographer's initial memoir and his inflation of his own importance in Schubert's life became so absurd that Kreißle wrote to him pointing out that, in order to follow Schober's account of things, Kreißle would have to assume that Joseph von Spaun, 'the personification of honesty and upstanding character' was a liar.

Franz von Schober in Dresden, 1859, photograph.

A few years later, in 1869, Schober extricated himself from any duty to record his times with Schubert when Bauernfeld – the professional writer interested in cashing in on the renewed interest in Schubert – wrote to him asking for his recollections of his soulmate. We hear Schober at his indolent worst:

With the best will in the world I cannot help you with your natural and justified request that I write down some Schubertiana. I have attempted doing this so often for myself, I would really like to have produced a little book about him and our life together but have never managed it. How can I make clear to you the unsurmountable inability to write? To you, one who writes so easily and elegantly, the inability that has driven me to despair me all my life and which has been the ill-fortune of my life?

I shall gladly, when we meet, tell you everything I know, but I can't write it down.

[…]

Don't imagine that it is a lack of good will or just inertia that holds me back, but that's how it is.

Deutsch Erinnerungen p. 236.

Schober's repellent need for recognition, to be someone special, is revealed, however, once he (mistakenly) thinks the submission deadline for Bauernfeld's piece has passed. It's quite nauseating:

I would really have liked to tell you about a sort of love story of Schubert's, which, I believe, no other person knows about because I, the only other one involved, has never told anyone about it. You could have decided what parts of it were suitable for publication, but now it's much to late for that.

Deutsch Erinnerungen p. 236.

The love story which only Schober knew stayed firmly inside his head. This remark of Schober's is ultimately pure mischief for the purpose of inflating himself: one scholar has already speculated about who Schubert's secret 'unknown love' might be.

In the following year, after Bauernfeld's piece appeared, Schober wrote to Bauernfeld complaining that he had mentioned Schober's acting career in Breslau. The Breslau adventure reflects badly on Schober however delicately it is retailed, so that we can understand Schober's embarrassment at his youthful enthusiasms. But his desire to suppress all mention of the incident is quite indicative of Schober's desperate need to shape history and put his curriculum vitae in the best possible light.

An interesting light on Schober's representation of his time with Schubert is given by his wife Thekla von Schober in a memoir written in 1891, nearly ten years after Schober's death, in which she recounts what she learned from Schober about Schubert. After passing through the mill of Schober's self-inflating psyche and then a few years of misremembering in Thekla's brain, the account is laughably worthless. We read, for example, that Schober visited Schubert on his death bed, but Schubert was wildly delirious by that time and did not recognise his old friend. Thekla recalls in particular the way Schubert's familiar eyes stared strangely and wildly at Schober.

Schubert really did not deserve Schober.

Closing the lid

After the death of Schubert in 1828, Schober would have 54 years of life left to him. How did he spend those years which his soulmate Schubert never had? In restless travelling, womanizing and self-promotion. He was granted not just a long life but many lucky breaks. Nevertheless, now Schubert has gone, Schober, whatever talents he had still undeveloped, becomes simply a footnote in other peoples' lives, just like his father did.

At the beginning of 1830 he became the companion/secretary of Leo, Count Festetics (1800-1884) in Budapest – 'Pest' at that time – and a governor to his children. The terms of Schober's employment were generous in both time and money. Schober, a restless traveller, kept a foot in Vienna, too. His mother died on 23 March 1833 and there followed a bitter inheritance battle with his uncle. Up until the 1840s his time in Vienna was marked by a number of affairs. He finally gave up his apartment in Vienna and continued with his travelling. We hear of him in Rome, Naples, Sicily, Florence and Paris.

Another chapter of his life opened when he met Franz Liszt in his employer's house at the end of 1839. Schober undertook some journeys with Liszt, possibly as a companion, but never with an official function. Once more, Schober attached himself to the coat-tails of a famous musician. One thing led to another: when Liszt moved to Weimar as Director of Court Music in 1842/3, Schober followed him. In 1844 he was appointed as Librarian to the Weimar Court and nominated as Legationsrat, a 'deputy ambassador', by Grand-Duke Carl Alexander (1818-1901). In his new, elevated position he began to keep a diary, essentially a list of all the important events and functions he had attended. He seems to have continued his taste for declaiming texts at reading evenings, this time from Goethe, the local champion. Schubert songs were also performed – unkind natures might suspect they would be the works for which he, Schober, had written the words.

Cutting many long stories short, by the 1850s, Liszt wisely began to distance himself from Schober, whose position at the court had been damaged by gossip over affairs and his generally irritating behaviour. Schober married Thekla von Gumpert in 1856, they separated tumultuously but not unamicably in 1859. He went to Dresden, to Budapest and finally to Munich, where he died on 13 September 1882.

Scales fall from eyes

Josef Kriehuber, Portrait of Moritz von Schwind, 1827.

Moritz von Schwind, the friend who during the Schubert years had most fallen under Schober's charismatic spell, reversed the polarity of his feelings for his one-time hero and became bitterly antagonistic. In 1846 he wrote to Bauernfeld:

Schober will think of himself as ill done by until the Indian eats Schober's excrement and Europeans, too. That comes from sponging off the fame of others.

Quoted in Waidelich Torupson p. 6.

The remark about eating excrement is an allusion to the popular story of the time, first mentioned in the Austrian Jesuit missionary Johann Grueber's (1623-1680) account of a visit to Lhasa around 1662, according to which the followers of the Dalai Lama worship him as a god and that their reverence is so great that they even eat his excrement for its medicinal properties.

Ten years later, in 1856, when Schwind heard of Schober's marriage, the man who had once himself revered Schober almost as a god wrote:

Once more I am amazed that someone has brought themselves to marry Schober. She must have been thoroughly sick of her good days up until now. Anyone who hasn't had the pleasure of having this man in their house for 14 days cannot begin to understand the affectation and embarrassment. It is indeed a stupid person who cannot grasp what an historic event it is when Schober puts on his trousers and his wife hands him the pomade pot with no less deference than Mary Magdalene oiled the feet of the Lord. I congratulate every woman whom this happiness has passed by.

Quoted in Waidelich Torupson p. 5.

In contrast, Franz Grillparzer never fell for Schober's charisma. In 1837, barely a decade after Schubert's death, he wrote:

There are, particularly in Germany, art lovers and dilettantes, who only love in other people's works what they themselves have inserted. Just like certain insects, which don't have enough of their own body heat to hatch their young, lay their eggs in others' bodies. […] Such people, in themselves harmless, are, as critics and friends, especially dangerous for practising artists. Schober is such a person.

Quoted in Waidelich Torupson p. 6.

For our final judgement on Schober and his influence on Schubert and his friends we consider two letters written in May 1858 by Joseph Kenner (1794-1868) in response to Ferdinand Luib's request for recollections of Schubert.

Kenner knew Schober in Kremsmünster. He was a talented writer, lifelong moraliser, slightly priggish, who, although recognising Schober's qualities, seemingly never succumbed to his charisma. Kenner's portrait of Schubert being led astray by Schober is not taken very seriously nowadays: it is not in tune with our allegedly non-judgemental times. However, it is at least consistent with what we know of Schober and his charismatic power over many of the friends.

In the first letter Schober remains unnamed. Kenner blames the unnamed person for leading Schubert astray, ultimately leading to the syphilis infection which, according to Kenner, brought about his early death.

Schubert's genius attracted, among other friends, the heart of a seductively likeable and brilliant young man, equipped with the noblest abilities, for whose extraordinary talents a moral foundation and strict control was as necessary as it was unfortunately missing. But this glittering individual spurned such restrictions as being unworthy of a genius, brashly rejected such limitations as merely prejudice and constraint. Dazzling with sophistry and flattering blandishments, he gained an unholy influence on Schubert's bourgeois impressionability. Although this did not appear in Schubert's work, it was all the more noticeable in his private life.

Those who knew Schubert were aware that two completely different natures were conjoined in him: how powerfully the hedonism in his character dragged him down into its sticky swamp and how influenced he was by the words of the friends he chose to esteem. Those who knew Schubert understand well how that led to his submission to the false prophet, who used the sensuality of soothing words so flatteringly. Even sterner characters were seduced by the demonic attractions of the demeanour of that person, who was externally warm but internally merely vain, leading them into the idolisation of him over short or long periods.

The recognition of this fact seems to me to be indispensable for biographers' understanding, because it affects an episode in Schubert's life which probably caused his premature death, certainly accelerated it.

Deutsch Erinnerungen p. 99f.

Luib pressed Kenner to name names.

The seducer of Schubert that I wrote about was Franz von Schober, whom I met in 1808 in the Kremsmünster school. After finishing his studies there he lived in his mother's house in Vienna, in which, following the insufficiently investigated death of his sister, who was married to the singer in the Court Theatre, Siboni, and that of his brother Axel, the Spauns, Mayrhofer, Enderes, Gross etc. were visitors. Derffel, a relative of the Schobers, was there, too.

[…]

Subsequent experience has shown, that in this family, under the veneer of pleasant conviviality, the deepest moral corruption ruled. It is therefore no surprise that Franz von Schober went the same way. He invented a philosophical system for his own convenience and for external justification, including the establishment of his own aesthetic oracle, about which he was probably as unclear as any of his young men. However, he found the mysticism of sensuality flexible enough to offer him plenty of scope – and his followers, too.

The needs of love and friendship were expressed so selfishly and jealously, that he alone became everything to his adherents, not just a prophet but a god who was unable to tolerate any other religion, any custom or limitation. Whoever did not worship him exclusively was unworthy of the elevation to Schober's intellectual level – and whoever turned away from him dissatisfied and could not be regained by his persuasion and his tears, through which Schober also convinced himself, was rejected as unworthy.

These characteristics also blurred his understanding of 'mine and thine', just as in marriage, in respect of the property of his worshippers. He gave out that which he did not require, but showed no reluctance to request it back when he needed it himself again, or to allow his friends to take over his obligations.

As far as women were concerned he was completely carefree, having only got to know two types: those by whom he was successful and who were therefore worthy of him, and those by whom he was not successful and who were therefore unworthy of him.

Strong, healthy natures, real thinkers sooner or later saw through his dazzling spell, such as Oehlinger, Moritz von Schwind; over others he won more persistent influence, among them Schubert's trusting nature, although I think I am right in believing that Schubert, too, later shook off this idolisation.

Deutsch Erinnerungen p. 101f.

Written forty years after the fact, Kenner's acount can be expected to have a number of defects. We are, for example, surprised to find Schwind's name among those 'strong, healthy natures' who shook off Schober's spell. Schwind did indeed – and then very decisively – but certainly in the Schubert years he had been Schober's most devoted lapdog. Kenner's comments also reveal how low the reputation of the Schober family was among the respectable gentry of Vienna: after all those years he still remembers poor Ludovica and whatever other scandals were attached to Schober's family at that time.

But, given everything else we have learned about Schober in our tour of his life with Schubert, most of what Kenner writes is in accord with a number of other accounts: the general tenor is quite credible. Kenner's prim requirement that artists should be morally impeccable – well, that's a discussion for another day.

Whether we like it or not, Schubert and his soulmate Schober fused into the 'Schobert': Schubert liked his drink and his tobacco and liked women as much as any introverted outsider could; Schober ditto and ditto and used women as much as any extroverted outsider would. Perhaps they really were made for each other, like the 'yolk and the white of the one egg'.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!