The cultural circles: 1815-1823

Richard Law, UTC 2016-12-09 06:46

The period 1815-1823, that is, the block of time between Schober's first meeting with Schubert and his departure from Vienna for Breslau we shall consider as a whole, without going into the details expected of proper biographers. This is the period of the famous 'Circles of Friends', an aspect that requires the proper biographer to discuss the many participants, assessing their individual roles and contributions along the way. If you want all that, then you will just have to read your way through the thousands of pages of Schubert biography currently available. Fortunately, we lazy, dilettante biographers can do it differently. Here is a list of the four main aspects of Schober's presence in this period, followed by some notes on each one. Pay attention you lot on the back row!

- Acquiring a singer: Johann Michael Vogl.

- Instituting the Schubertiaden, the musical evenings.

- Instituting the Lesegesellschaft, the reading society.

- Muse, poet, lyricist, soulmate, libertine, landlord

Leopold Kupelwieser, Franz von Schober, 1821.

1 Enter Vogl

The song-machine that was the young Franz Schubert was churning out Lieder almost as though they were sausages. The young genius needed to have these songs performed in public and for that he needed a good singer. It was Franz Schober who, through his brother-in-law, Giuseppe Siboni, the widower of poor Ludovica Schober, contacted the renowned tenor-baritone, Johann Michael Vogl (1768-1840), and asked that he meet Schubert.

Why Vogl and not just Siboni, you ask? The most likely answer is easy: Schubert was setting German texts to a music that was firmly rooted in the tradition of the Austrian-German Volkslied. Siboni, even if he had had Vogl's standing in the music world, would have been quite the wrong person to sing Schubert Lieder.

Vogl was nearing the end of an impressive career as an opera singer in Vienna. He had acquired his first position in Vienna in 1794, that is before Schubert (1797) or Schober (1796) had been born. He not only had a fine baritone, but he was tall and striking – an imposing stage presence, think of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (1925-2012) or Richard Angas (1942-2013) in our day – and was predestined to fame as an opera singer. Until his retirement in 1821 his career blossomed. Baron von Schönstein, who would also be a noted performer of Schubert's work, had been his student.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Portrait of Johann Michael Vogl, 1821.

Opera singers cannot go on for ever blasting their voices to the back row in large, noisy theatres, night in and night out. For that reason, Schubert and his songs arrived at the right time for Vogl. They allowed him to change gear: sing easily rehearsed, easily memorised pieces to small audiences in intimate surroundings, yet still receive that most addictive of fixes, the acclamation of an audience.

His musical seniority made it difficult to argue with him, a seniority perhaps approaching pomposity for the youngsters around the young composer. Vogl was no mere singer: he had had a university education in Law and Philosophy and wore his tastes and learning in the classics on his sleeve so publicly that he was known as the 'Greek Vogl'. He might be seen immersed in classical works even backstage during performances. Joseph von Spaun, always measured in his judgements, never hyperbolic, characterised him as eigensinnig und stolz 'obstinate and proud'. Unkind hearts might prefer the translation 'pig-headed and arrogant'. Schober's famous satirical caricature of Vogl and Schubert 'setting off to do battle with the world' is not only viciously accurate about Schubert, supposedly his great friend, but also viciously accurate about Vogl, the proud giant in the lead, oblivious to everyone else, with the little composer trotting behind him. Was this how it really was? – we shall never know.

Schober's caricature of Schubert and Vogl 'setting out to battle and victory'.

We do know that when the young friends learned in 1826 that the man they knew as the crotchety, gouty, 58 year-old confirmed bachelor was to marry, and not only that but to marry a 26 year-old, they were stunned. Even more stunned when a daughter arrived. Vogl would outlive Franz Schubert by exactly twelve years, dying on the same date as he: 28 November.

Schober pestered Vogl long enough to overcome this elevated personality's resistance. Vogl finally met Schubert in Schober's apartment in the autumn of 1817. After some prompting, he appreciated the quality of Schubert's work and seized the chance to take a new career direction (although it was never expressed as such).

It may have been Schober's persistence that started this ball rolling, but Vogl never succumbed to Schober's 'charisma'. After years performing on the greatest stages of Vienna to the most discerning audiences of the Empire, Vogl had his own supply of charisma. The rule seems to be: there can only be one charisma in a room at any one time. In this case we can be sure that it would be Vogl's.

'You can't always get what you want' as another singer put it in 1969. It has to be said that Vogl brought his fame, authority and reputation to Schubert's songs, but the youngsters around him had not only to walk on the eggshells of his brittle personality but also to put up with the mannerisms of his performing style. The transition from the opera stage to the drawing room cannot have been easy for Vogl and we note the occasional comment concerning his affectations.

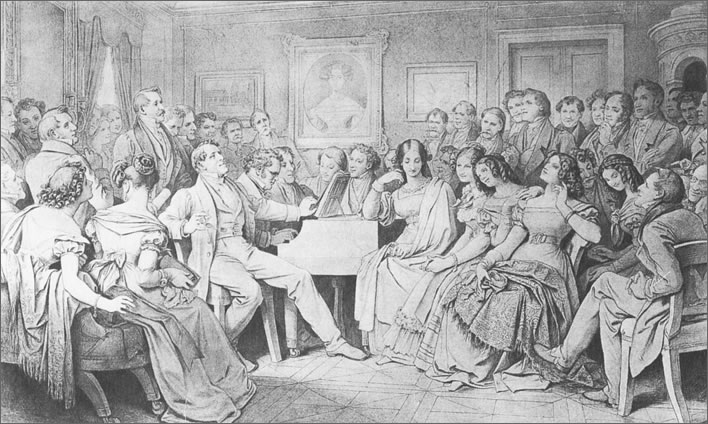

For example, after a Schubertiade on 15 December 1826, Eduard von Bauernfeld, the writer who succumbed to no one's charisma, noted in his diary two days later that Vogl had sung 'masterfully, but not without Geckerei' – 'affectation' or, more unkindly, 'clowning' – and that he had attempted to compensate for the decline of his voice by the use of gesticulation. This was, by the way, the great Schubertiade which Moritz von Schwind is supposed to have used as the basis for his famous drawing, in which we are shown Vogl reclining, waving his arms around and generally behaving like an opera singer. Schubert – ironically, the composer who hated an affected singing style and mangled time-keeping – seems to have coped with this somehow.

Moritz von Schwind's homage to a Schubertiade. This was drawn in 1868, 40 years after Schubert had died, and is therefore not a portrait of any particular event but more of a group portrait of the people in Schubert's life.

Vogl is drawn gesticulating, the Geckerei to which Bauernfeld objected.

As we noted in a previous piece: in the second row on the right of the picture Franz von Schober is flirting with Justina von Bruchmann. They are the only ones not listening to the performance. Schwind is reminding us that Schober entered into a secret engagement with Justina (whose father was probably the richest man in Vienna). This plan was discovered and the engagement dissolved in 1823, leading to a break between Schober and her brother Franz von Bruchmann, a leading figure in the Schubert circles. By the time he created this group portrait Schwind had himself developed a deep loathing for Schober, a loathing that is unmistakeably revealed. Revenge is a dish that needs to cool for 40 years before it is eaten.

But, despite all this, Vogl was the instrument who performed the young composer's work and helped to get him an albeit somewhat exclusive Viennese public and for that we ultimately have to thank Franz von Schober.

2 The Schubertiade, curse or blessing?

In January 1821 Schober invited some 'good friends, preferably 'spirited men' to an evening at his house. Schubert himself would play a lot of 'wonderful songs' and afterwards 'punch would be drunk'. The name Schubertiade had not yet been invented, but this event, programmatically mentioning Schubert and his music, can be considered the first of the series.

As far as we know Schober was the prime mover behind the Schubertiaden. It is presumed that it was he who came up with the name Schubertiade, that fine piece of branding that set Schubert and his music in the centre of the event. The word not only bound Schubert to the event, it also gave no indication to the secret police – the narks and 'bluebottles', those historian's friends – that anything else might be happening. When the music stopped and the punch was drunk and the dancing started we know nothing of what was discussed in that round: in those dangerous times nothing of importance was written down, even in the most private diary. Viennese culture had become an oral culture long before this and as such its detail is lost to us.

No one in the circles of friends would have forgotten the case of poor Johann Chrysostomus Senn, that inspirational hothead, who had been one of the great intellectual figures of the Schubert circles and a great friend to the young Schubert before Schober came on the scene, but who, only a year before this first Schubertiade, had been arrested, his notebooks read, had been beaten, locked up and starved by the police for nearly a year before being exiled to his homeland, the Tyrol, his prospects in Franz II/I's Austria forever blighted. Some members of the circles kept in discreet and risky contact with him in exile, this bright, fulminant friend. They could only watch from the sidelines as his once-promising life now disintegrated into long years of pointlessness, which is the ultimate fruit of repression when it doesn't just kill you.

Names, once written down, led to other names and soon conspiracies could be found anywhere. Franz Grillparzer (1791-1872), plagued by censorship throughout his career, remarked to Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) in 1823 that composers were fortunate because the police and the censors had no idea what they were thinking when they wrote their music.

Repression works by instilling fear and caution: walls had ears and everyone in Vienna would have had an anecdote about that. No one was immune: in November 1825 the renowned miniaturist Moritz Daffinger (1790-1849), whose work was commissioned and collected by the aristocracy and Franz II/I himself, was overheard by narks in the tavern 'Archduke Karl' to say some critical things about the military. His friend Grillparzer was with him and joined in the grumbling. A couple of months later they were both rounded up and subjected to several months of investigations. The process was also part of the punishment. Daffinger was given three days' police arrest ('police arrest' meaning that the punishment was summary and not subject to due process). Grillparzer, a civil servant, was reprimanded and threatened with worse should anything like this happen again.

We enjoy the ironies of history on this blog and Clio rarely disappoints: Daffinger is particularly known for his work for the Metternich family – Metternich, the great architect of Franz II/I's intellectual freeze across most of Europe – and for his delightful watercolour of Josef Graf Sedlnitzky, head of the Police and Censorship department, a work that makes the old monster look rather louche and interesting.

Moritz Michael Daffinger (1790-1849), Graf Joseph Sedlnitzky, 1837. Image: Beaussant-Lefevre, Paris

Nor would the Spauns – Joseph, Anton and Max – have forgotten the lesson of their hothead, contrarian uncle, Franz Seraph von Spaun (1753-1826), who had spent eight years on the 'Dungeons of the Empire' tour. He had been in exile in Bavaria since 1801, continually persecuted for his opinions.

Even Schubert's father, now Director of the school in Rossau, could thank his predecessor's expressions of contempt for religion and the state, also overheard in a tavern, for leading to his destruction and thus making that post available to Schubert in the first place. Can anyone argue that Schober, Schubert and friends did not think long and hard about the official perception of their invitation-only evenings? The Jacobin trials from 15 years before had become a folk memory for the Viennese but were still present in the minds of Franz II/I, Metternich and the police ministers. Their lesson had been learned: distrust any congregation of people, fear any private gathering, fear students, fear the young.

The first time we hear the name Schubertiade used is on November 1821. The event took place in St. Pölten in the palace of Bishop Dankesreither, the special friend of Schober's mother. After that the events hit their stride and generally took place once a week. We only know of a few documented instances, because they were not in their nature public events.

The question of whether the Schubertiaden brought Schubert any tangible benefits has already been discussed on this blog here. In essence, although his name was on the tin, Schubert was the entertainer at an event hosted by others, usually Schober in the early years. The fame of the composer was enhanced within the limited circle of the guests, but Schober's profile was also enhanced within that cultured milieu. He, that social butterfly, gained the most from these events. As already noted, the first named Schubertiade took place for the lover of Schober's mother. What could that provincial little group possibly offer Schubert? The only beneficiary was Schober.

The present writer is convinced that Schubert gained no substantial advantage from these events apart from admiration, respect and a feeling of belonging. Well, we all like those. They may have been an important psychological gain for him and may even justify Joseph von Spaun's opinion that the Schubertiaden had been essential for his development: Schubert would not have been Schubert without them. But the fact that Spaun feels the need to write this at all exposes the question: whilst accepting the psychological gain, what was the professional gain for Schubert?

As we wrote in a that previous piece the Schubertiaden were fundamentally selfish events – they kept their house musician busy entertaining their guests, paid him nothing, gave him a buffet and some drink and kept the knowledge of his talent as a composer, his genius and fame, firmly bottled up in the febrile, self-regarding scene of the Viennese salon. The typical conclusion of Schubert's salon appearances was a sausage supper, some drinking and then some dancing, as Schubert, the resident piano-player, probably with the help of another pianist such as Joseph von Gahy, would be expected to knock out gallops and ecossaises into the early hours of the morning. After about midnight the ladies would be escorted home and the men would then retire to a coffee-house for a nightcap and a smoke.

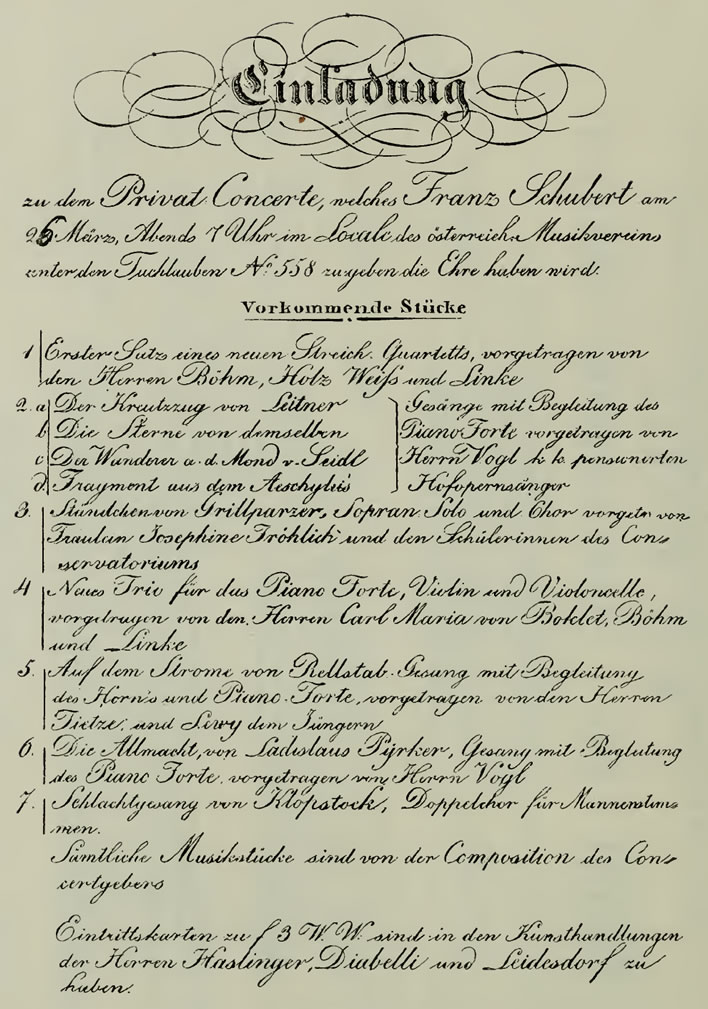

Your gloomy author exaggerates, as so often? On the 26 March 1818 Franz Schubert gave a 'Private Concert' in the hall of the Austrian Music Society in Vienna. At last! we murmur, at last! The hall was packed, the audience reception ecstatic, the reviews equally so. The net income for Schubert was 800 florins W.W. (= 320 Gulden, fl. K.M.). On the downside, he did not get free sausages to eat or punch to drink and he did not need to spend a couple of hours afterwards playing dance music for the guests. He still got to go to the coffee-house afterwards.

The programme for Schubert's one and only concert, 26 March 1828. Schober would surely have noticed that none of the pieces performed are based on his texts.

All the evidence we have indicates Schubert's tremendous happiness and satisfaction during the period after that concert. Music publishers were also beginning to compete for his work. After seven years of entertaining his friends in Schubertiaden, he had at last done something that was professionally worthy of his talent. He had only six months to enjoy that unusual condition before death came to call.

The driving force of the first phase of the Schubertiaden disappeared in 1823 when Schober left Vienna for Breslau. The series fell apart, but not just because of his absence. Many of the key people were elsewhere, fewer evenings were held, Vogl only sang when he had an important audience, Schubert's voice, though pleasant enough, was not in the same league.

But most importantly, Schubert was going through a difficult time with his health and his psyche. We should not underestimate the effect of this on his sociability. He was 'recovering' from syphilis and recovering from the treatment, a treatment which might be considered to be not much better than the original disease. He went bald and had to wear a wig until his own trademark curly hair reappeared. Syphilis was a fact of life in those days, but – associated as it was with immoral behaviour – it was not a fact that one mentioned in polite society. His intimates would undoubtably have known about his illness, but there would have been a period of purdah after the course of treatment.

After the hiatus the weekly Schubertiaden restarted in 1825 under the aegis of two senior civil servants, loyal and devoted Schubertians both, Karl von Enderes (1778-1861) and Josef Wilhelm Witteczek (1787-1859). At these events Vogl sang – the sponsors had the rank that Vogl needed – and at one point, we are told, up to 20 people attended. Joseph von Spaun returned to Vienna in the spring of 1826 and became the motor for the reawakened series. The Schubertiaden would run for another two years.

And Schober, earlier the leading light? From the evidence we have, Schober appears to have attended these later Schubertiaden frequently. He also joined in the traditional coffee-house debriefing that followed around midnight. But we can say that he is no longer in the centre of the action around these events. After his return from his Breslau adventure he sank into an ineffectual torpor. During his two-year absence in Breslau others took the initiative: rich civil servants such as Enderes, Witteczek and particularly Joseph von Spaun, now on the curve of a substantial career.

The last Schubertiade that took place with Schubert's presence was also held at Spaun's residence on 28 January 1828. Ten months later Schubert was dead. Schober's brand name Schubertiade survived the death of its eponymous star and is still being used today for concerts of Schubert's music.

3 The Lesegesellschaft

We know almost nothing about the Lesegesellschaft, the Reading Club, and the Leseabende, the Reading Evenings that the Schubert friends held. That lack of knowledge about such intellectual gatherings is a characteristic of those repressive times. Censorship and the secret police – at that time the two sides of the same coin – made sure that all the most interesting works were difficult or impossible to obtain. Public discourse was very dangerous: in those times serious discourse took place in private, if it took place at all. Franz II/I's 'belljar', as we have called it, was extremely effective.

As far as we can tell there were Reading Clubs of one sort or another all over Austria. Meetings were held in private, only reliable friends were invited and nothing whether – invitation, programme or minutes – was written down. That's how it was in Franz II/I's empire of calm.

We think this Lesegesellschaft was initiated by Schober, who once again put himself at the centre of things. The first we hear about it is in a letter of Schubert's in December 1822 that readings took place 'three times a week' at Schober's residence – we assume in the autumn and winter months. At the core of the meetings seems to have been a reading of some text by Schober, who had an imposing bass voice capable of a volume that could crush all other speakers. The reading was probably followed by some sort of discussion, which in turn was followed by a retreat to a coffee-house. Schober finds himself once more in the spotlight with an admiring audience in front of him. Just as with the Schubertiaden, we grumpy bystanders wonder who benefitted most from these meetings. Our answer is the same now as it was then: Schober.

The hints and scraps we have lead us to believe that the quality of the meetings decayed rapidly in 1823, the final nadir being reached after Schober's departure for Breslau to become… an actor! In other words he would now be in the spotlight in front of a larger audience. His Reading Club baby was left in Vienna to look after itself. On the state of the Lesegesellschaft Schubert wrote to Schober in Breslau on 30 November 1823:

Although we got four people as a replacement for you and Kupelwieser … the preponderance of people like that make the club more meaningless rather than more useful. What use is a group of common or garden students and civil servants? When Bruchmann is not there or just ill then under the leadership of Mohn one just hears for hours on end about nothing but riding and fencing and talk of horses and dogs. If it goes on like that much longer I probably won't be able to stand it anymore.

Deutsch Dokumente p. 207.

Why do we grumpy people assume that Schober would be deeply flattered by that account?

Schubert did cease attending soon after that letter. The club carried on for five more months with its 'rough choirs in beer drinking and sausage eating' until April 1824, when it was 'formally suspended'. A core group may have continued to meet less formally for all we know. The Reading Club was restarted around the beginning of 1828, once again by Schober, after he returned to Vienna from Breslau. This time the group met once a week on Saturdays.

Schubert scholars like to think that the Lesegesellschaft played an important role in Schubert's intellectual education. It's a nice thought that the composer, who, thank goodness, never attended a university course and who, thank goodness, did not waste valuable composing time reading Kant, Hegel or Schlegel, was exposed by the Reading Club to the intellectual discussions and the intellectual currents of the time that he may have missed. Unfortunately, there is not the slightest bit of evidence for this assumption. We know a few of the works which Schober declaimed in his hypnotic bass voice during the later series of meetings, but among these there is nothing that can be considered of cultural or literary importance.

4 Muse, poet, lyricist, soulmate, libertine, landlord

What else did Schober do for Schubert in the years 1815-1823? Here follows the executive summary, in no particular order.

He wrote 17(18?) poems that Schubert set to music, most famously the maudlin, derivative poem An die Musik, 'To Music', to which, around 1817, Schubert did what he could do so well: set an execrable text to wonderful music and thus ensured its immortality. The text is still indigestible stodge in a genre and style that was old-fashioned when it was written, but there are uncritical, happy people who find such doggerel pleasing – as long as it is sung to Schubert's music. It is barely conceivable that anyone reads this gruesome text as a poem.

Schober wrote the text for the opera Alfonso und Estrella in 1821, which Schubert, almost working in parallel to Schober, set to music. The work is so good that, to my knowledge at least, no one has ever tried to perform it uncut. Even Schubert's singer friends, Vogl and Milder, expressed reservations. It was rejected during Schubert's lifetime and several times after until, in 1864, Franz Liszt (1811-1886) directed a shortened version in a first performance in Weimar. Liszt even suggested, much to Schober's disgust, that one should keep Schubert's music but throw away Schober's text and start afresh. Liszt knew exactly what the negative reaction of public and critics would be and he was right. Subsequently it has had occasional 'curiosity' performances, but only ever in a cut version.

The grounds for its rejection and its mutilation have always been the deficiencies of the text, not the music. If the text seems as though it was written by a dilettante who had never written an opera before, your perception would be right. It should be enough to know that when the Viennese censor raises not one single objection to a libretto, something is seriously wrong.

The labour which Schubert put into it was not completely wasted, since he was able to recycle parts of it for other purposes, but we can only regret the distraction this flawed work caused our musical genius. It was a joint project between Schubert and Schober, meaning that Schubert never saw the whole before he started composing.

Schober is also supposed to have been instrumental in pointing Schubert to Wilhelm Müller's poem cycle Die schöne Müllerin as well as the later Die Winterreise. As usual there is no solid evidence for this at all, apart from a late rambling of Schober's in an interview half a century after the fact.

It is often assumed that it was that dissolute libertine Schober who led poor little Schubert astray in the red-light districts of Vienna. For obvious reasons no one recorded these adventures if they took place, not even the 'bluebottles', so, as usual, we have no evidence at all for this assumption. For more than a century, Schubert scholars have poked about pruriently in the subject of Schubert's 'illness'. There is little doubt that it was syphilis, which, as is well known, you don't pick up from walking down the street. Vienna was the prostitution capital of Europe. We only need to remember Franz II/I's remark, when someone proposed setting up an 'official' brothel in Vienna: 'You may as well just put a roof over the whole city'.

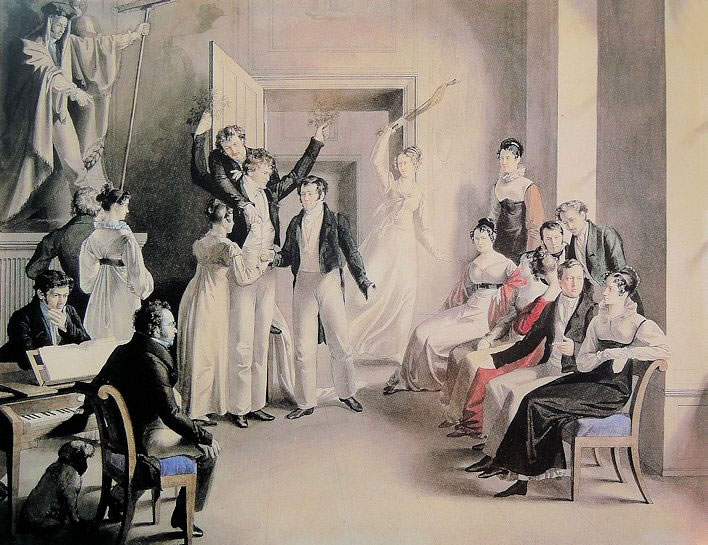

Leopold Kupelwieser: Der Sündenfall 'The Fall of Man', 1821, watercolour (Wienmuseum). An illustration of a game af charades among the Schubert friends in the summer of 1821.

The picture illustrates the charade for the second syllable of the word Rheinfall – Fall, in this case the 'Fall of Man'. The illustration was done by Leopold Kupelwieser for Schober. In 1876 Schober wrote an explanation of the picture for Hyazinth Holland [Otto Erich Deutsch, Erinnerungen, 14 February 1876, p. 238.]. Kupelwieser is the tree of knowledge. Adam and Eve have just received the apple from the snake, played by… Schober, who else? He seems to be proud to have been selected as the snake bringing Original Sin into the world. The angel with the flaming sword stands ready to escort Adam and Eve through the door and off the premises.

Whilst on this subject we need to clear the biographical undergrowth more thoroughly. It is sometimes asserted that Schober also contracted the disease. There is no evidence for this at all. He lived a long and healthy life and there is no evidence of the kind of treatment and hair loss that Schubert had to suffer, unless, of course, Schober has managed to purge any mention of that from the record.

It is also sometimes asserted that Schubert picked up the disease in 1818 during his first stay at Zselíz as a result of a fling with the chambermaid – later lady's maid – there, Josepha ('Pepi') Pöcklhofer (1797-1879). This is an outrageous slur on Pepi's character made without any evidence or logic: the disease manifested itself in Schubert in 1823, which would have to be only a short time after infection. Pepi led a long and materially successful life.

Schober's role as Schubert's soulmate we have already discussed, but Schubert's need for that soulmate is clear. With or without Schober's charisma, his literary affectations, his money, his butterfly unpredictability and his impresario role, Schubert, right up to the end of his life, liked him. He cheered Schubert up and for that we should probably be grateful to him.

For completeness: during the eight-year period 1815-1823, Schubert lived in the Schobers' residence for two phases. Firstly, from autumn 1816, after Schober returned from his trip to Sweden to autumn 1817, when Axel Schober was supposed to be returning (but died en route). Then secondly, from the beginning of 1822 to November 1823, after which Schober left for Breslau.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!