Franz Schubert in search of lost time

Richard Law, UTC 2018-09-01 16:37 Updated on UTC 2018-09-07

Zseliz 1818: young and homesick

Readers of our account of Schubert's first stay on the country estate of Count Johann-Karl Esterházy de Galántha in Zseliz in 1818 will surely recall how delighted he was to leave and get back to Vienna.

… As happy as I am, as healthy as I am, as good as the people here are, I am looking forward again and again to the moment when I hear: To Vienna, to Vienna! Yes, beloved Vienna, you contain the dearest and the most loved in your narrow confines and only a reunion, a heavenly reunion will still this longing.

… So wohl es mir geht, so gesund als ich bin, so gute Menschen als es hier gibt, so freue mich doch unendlich wieder auf den Augenblick, wo es heißen wird: Nach Wien, nach Wien! Ja, geliebtes Wien, Du schließest das Theuerste, das Liebste, in Deinen engen Raum, und nur Wiedersehen, himlisches Wiedersehen wird dieses Sehnen stillen.

[Dok 64 24 August 1818: Schubert to his brother Ferdinand]

He had been giving music lessons in Vienna to the two Esterházy daughters, Marie and Caroline, so when the family retreated for the summer from Vienna to the country house in Zseliz it was a reasonable thought that Schubert, the family 'music master' should go with them.

It would earn him some money – 75 florins a month, not very much but better than any other income source of his at the time – and he would have some relief from his father's schoolhouse and from his currently dreary situation in Vienna. It was his first journey over any distance, bringing the excitement of travel for the 21-year-old and the prospect of some peace and quiet to carry on composing, away from the oppressive Viennese summer.

On that first visit he was treated as a domestic servant: he ate modest food with the staff, had a room in the servants' quarters at first until he was allotted a room in the castle manager's quarters. Despite the human comforts of the friendly and understanding chambermaid Pepi Pöcklhofer, the isolation of the estate, the lack of intellectual fellowship and stimulation began to press down on him not very long after his arrival. Over the months of that summer in Zseliz the feelings of frustration grew: his happiest moment that autumn must have been the day he climbed into the coach home.

The following year, 1819, the Esterházys hired the Czech nonentity Leopold Eustach Czapek (1792-1840) as their music master, but of that tenure we know nothing more and Czapek himself has sunk into almost total obscurity. Nor do we know whether other music masters were hired during the four years before Schubert returned.

Having read about the relief Schubert felt at leaving Zseliz in 1818, the reader now asks: why then did he go back there in 1824, six years later?

Zseliz, 1824: older and wiser

In the summer of 1824, the circle of friends that he had missed so much on his first visit was barely there: Franz Schober was in Breslau, Leopold Kupelwieser was in Rome, Josef Spaun was in Linz, Johann Senn was in exile, Moritz Schwind was planning to go to Linz and Salzburg – perhaps even to Dresden to see Schober, the reading club had collapsed. In leaving Vienna that summer, there was not all that much to leave behind.

Syphilis had struck him down the previous year and its grip was still on him. He was attempting to follow a health regime with modest food and minimal or no alcohol. In Zseliz the temptations of Vienna that he found so hard to resist were not so omnipresent – we recall his satirical remark from 1818 that, after six weeks of being there 'so far he had been spared roast meat'.

In 1824 his status was much higher. He was still doing the Esterházy's musical bidding, but now he had his own rooms in a separate building. He even seems to have breakfasted with the family, too.

This time round he had an income of 100 florins a month, which was better than the 75 florins a month he had been paid during his first stay and better than anything he was earning in Vienna at that moment. That, plus board and lodging and a considerable amount of free time. During 1824 his earnings had been meagre and erratic, but as Joseph Spaun said in his memoir of him, financial matters were not his strength. At least here he had a guaranteed 100 florins every month.

Whether he still thought Count Esterházy 'coarse' – his characterisation of him in 1818 – we do not know, but at least this time Baron Schönstein would be there, the tenor-baritone who had come to specialise in the performance of Schubert's songs, so at least there would be someone else with whom he could converse. Schönstein was a close friend of Count Esterházy and it was probably Schönstein's admiration for Schubert that had caused the change in the composer's status over the intervening years. And Pepi Pöcklhofer was still in Zseliz, as would be Countess Caroline, Count Esterházy's second daughter.

In sum, then, a stay of a few months in Zseliz promised to be a reasonable way to extract himself from the current bleakness of his Viennese existence, much as it had done in 1818.

The sparse record

Schubert left Vienna with the ordinary postcoach on 25 May 1824, arriving in Zseliz after two overnight stops on 27 May. After an initial short stay in a room near the kitchen he moved out to the Eulenhaus, the 'Owl House' about 150 m away from the house.

Schubert's letters from Zseliz in 1824 (the few we still have) lack the fizz of excitement of those that the 21-year-old wrote in 1818, on his very first excursion from home. This time there are no excited letters intended to be passed around between numerous addressees.

Nor is there any witty description of his life in Zseliz and the people in it. Pepi Pöcklhofer was still there – now a lady's maid – but her presence goes unreported in 1824. After the gentle innuendos in his letter back to the boys in 1818, in 1824, as far as we know, he wastes not a word over her. Her future husband, Joseph Rößler, arrived in Zseliz in 1826. All we hear about her in the Schubert correspondence is an oblique reference by his father to an 'obliging lady's maid' who delivered one of Schubert's letters to his parents in person.

Nor does Schubert mention in the correspondence we have any of the staff at Zseliz – unsurprising, since he is now separated from them in residence, routine and status. In the six intervening years Schubert's life has changed and Schubert himself has changed – he is older, sadder and wiser. In short, he has grown up.

The portable depression, at home everywhere

When we were dealing with the subject of Schubert's syphilis infection, a letter he wrote to Kupelwieser on 31 March 1824 opened up a rare view into Schubert's damaged psyche: deeply depressed, apparently near suicidal but simultaneously still fully absorbed into his musical world, despite all his personal setbacks.

Three and a half months later, when Schubert is now in Zseliz, we find another revealing letter from him, this time to his brother Ferdinand on 16-18 July 1824. Ferdinand had written to him on 3 July, his first letter since Schubert left Vienna for Zseliz at the end of May. Ferdinand had let the whole of June go by without writing to Franz and now tells him how often he had thought of him: he played his quartets with Ignaz and friends and he thought of him whenever he heard the carillon of the clock of the tavern Zur ungarischen Krone playing his brother's walzes. Good reasons for a burst of mocking self-pity from Franz:

It would be better if you all kept to other quartets than mine, because there is nothing to them, unless they possibly please you, you who are pleased by everything from me.

Aber besser wird es seyn, wenn Ihr Euch an andere Quartetten als die meinigen haltet, denn es ist nichts daran, außer daß sie vielleicht Dir gefallen, dem alles von mir gefällt. [Dok 250]

We noted in our account of his previous stay in Zseliz that Schubert closed many letters with a request to the recipient to write soon. He now reproaches Ferdinand for leaving it a month before writing to him. Schubert himself, however, was no paragon as a letter writer. An example of this is a letter of his from Zseliz to Moritz Schwind in August. Schubert apologises airily for not writing to Schwind for three months, then demands, without a trace of irony, an immediate response:

I ask you to answer me all these questions as precisely as possible and a quickly as possible. You cannot believe how much I long for a letter from you. And since from you there is so much to be learned about our friends, about Vienna and a thousand other things, whereas from me there is nothing to be learned …

Ich bitte Dich beantworte mir alle diese Fragen aufs genaueste u. so bald als möglich. Du glaubst nicht, wie ich mich nach einem Schreiben von Dir sehne. Und da von Dir so viel über unsere Freunde über Wien u. tausend andere Sachen zu erfahren ist, von mir aber nichts …[Dok 255]

Franz aims a fine piece of Wiener Schmäh, 'Viennese mockery', at Ferdinand:

Your memories of me are the most pleasing to me, especially since they seem to affect you less than the waltzes from the ungarischen Krone.

Die Erinnerung an mich, ist mir noch das Liebste dabey, besonders da sie Dich nicht so zu ergreifen scheinen als die Walzer bey der ungarischen Krone. [Dok 250]

Warming to his theme of self-pity, Franz continues:

Was it merely the pain of my absence that brought the tears, that you could not trust yourself to write? Or, in thinking of me, one who is burdened by an eternal, incomprehensible longing, did you also feel to be wrapped in its dismal veil? Or did you remember all the tears that you already saw me weep?

War es bloß der Schmerz über meine Abwesenheit, der Dir Thränen entlockte, die Du Dir nicht zu schreiben getrautest? Oder fühltest Du beym Andenken an meine Person, die von ewig unbegreiflicher Sehnsucht gedrückt ist, auch um Dich ihren trüben Schleier gehüllt? Oder kamen Dir alle die Thränen, die Du mich schon weinen sahst, ins Gedächtniß? [Dok 250]

Having reproached Ferdinand sufficiently, he douses him with a declaration of a particular affection:

Whatever. I feel it more clearly in this moment that you or no one else is my closest friend, bound to me with every thread of my soul!

Dem sey nun, wie es wolle, ich fühle es in diesem Augenblicke deutlicher, Du oder Niemand bist mein innigster, mit jeder Faser meiner Seele verbundener Freund! [Dok 250]

In all communications between the Schubert siblings we should remember the family dynamics: Ferdinand (18.10.1794), Karl (05.11.1795) and Franz (31.01.1797) had been born within less that three years of each other, whereas Ignaz (08.03.1785) had been born much earlier. He was 12 years older than Franz, and was the sole survivor in the family until the three brothers arrived.

Finally, after the mockery and the expression of love, Franz gets down to saying something serious. Our ears prick up:

So that these lines do not perhaps mislead you into believing that I am not well or not cheerful so I rush to assure of the opposite. Admittedly, it is no longer that happy time in which every thing appeared to be surrounded in a youthful glory, rather the unpleasant recognition of a miserable reality, which using my imagination (thank God) I try to beautify as much as possible.

- Damit Dich diese Zeilen nicht vielleicht verführen, zu glauben, ich sey nicht wohl, oder nicht heiteren Gemüthes, so beeile ich mich, Dich des Gegentheils zu versichern. Freylich ists nicht mehr jene glückliche Zeit, in der uns jeder Gegenstand mit einer jugendlichen Glorie umgeben scheint, sondern jenes fatale Erkennen einer miserablen Wirklichkeit, die ich mir durch meine Phantasie (Gott sey’s gedankt) so viel als möglich zu verschönern suche. [Dok 250]

Franz dives further into his soul and meditates on the irrecoverable nature of past happiness:

One believes that happiness still hangs around in those places in which one was once happy, although it is only really in ourselves, and so I experienced an unpleasant delusion and saw an experience that I had already had in Steyr repeated here once more, but now I am more able to find happiness and peace in myself than previously.

Man glaubt an dem Orte, wo man einst glücklicher war, hänge das Glück, indem es doch nur in uns selbst ist, u. so erfuhr ich zwar eine unangenehme Täuschung u. sah eine schon in Steyer gemachte Erfahrung hier erneut, doch bin ich jetzt mehr im Stande Glück u. Ruhe in mir selbst zu finden als damals. [Dok 250]

Can there be a clearer expression of Schubert's deeper motives for going to Steyr in the middle of the 1823 turmoil of his syphilis? We can also now answer the question we posed above, the question of why Schubert should choose to return to Zseliz in 1824, given his joy at leaving in 1818. Now he tells us that by 1824, after all the misfortunes of the intervening years, the recent serious illness and the disappearance of many of his friends, he looks back on that summer of 1818 as one of happiness. He thought he knew what unhappiness was then; now, after all he has gone through – now he knows.

Schubert has discovered that the true location of the genius loci is not the hearth, but the heart – an idea that Marcel Proust would pursue 85 years later.

Just as in his letter to Kupelwieser on 31 March 1824, in which he opened his heart and then closed it again, he now closes the opening here with some musical chit-chat. Suddenly we are in another world. We note now as we did then Schubert's remarkably compartmentalised professional work-ethic.

Such workmanlike chatter about his music should not deceive us into overlooking the reality of his situation. In his March letter to Kupelwieser he had faced the economic failure of so much of the work he had produced, particularly opera music. On that occasion we quoted Joseph Spaun's opinion that Schubert's money management skills left a lot to be desired.

In fact, those skills were not just defective, they were weakened by desperation, as we can see from a letter he sent to the author Helmina von Chézy from Zseliz on 5 August. She had been touting her play Rosamunde to the Theater an der Wien and wanted Schubert to quote a fixed price for writing the music to it. Schubert responded:

As far as the price of the music is concerned, I believe that I cannot set it below 100 florins C.M. without compromising the music. Should that however be too high I would ask you to set the price yourself, without departing too far from the sum stated and send [the text] to me at the address below [Rossau].

Was den Preis der Musik betrifft, so glaube ich ihn nicht unter 100 fl C. M. bestimmen zu können, ohne ihr selber zu schaden. Sollte er aber dennoch zu hoch seyn, so würde ich E. W. bitten, selben, doch ohne zu großer Entfernung von der angegebenen Summe, selbst zu bestimmen, und dessen Überlieferung in meiner Abwesenheit unter beygefügter Adresse zu befördern ersuchen. [Dok 252]

In other words: I want 100 florins, but I shall accept whatever you want to give me.

On 14 August we have a bundle of letters from Schubert's family. The one from his father is interesting for a number of reasons:

Your letter, which the obliging lady's maid handed us personally on 31 July gave me and all of us a special happiness.

Dein Schreiben, welches mir die gefällige Kammerjungfer am 31. v. M. eigenhändig überreichte, dient mir u. all den Unsrigen zum besonderen Vergnügen. [Dok 253]

It is assumed that the 'obliging lady's maid' must be Pepi Pöcklhofer herself, about whom we must presume that Schubert's father knew nothing more, otherwise he would have mentioned her by name. Pepi was well brought up and as the lady's maid to a 'proud' Countess had all the social graces and personal empathy required to deal with the fastidious schoolmaster.

Schubert's father, the pious moralist, who admitted to his son in an earlier letter (June 1824) that moralising was an occupational hazard for him as a schoolteacher, [Dok 245 'daß ich als Jugendlehrer immer gern moralisiere'.] hinted at his relief at an apparent change of lifestyle in his son:

I am even happier at your current feeling of wellness, because I assume mainly that you intend to have a happy future. This is also my daily plea to the loving God, that he enlightens and strengthens me and my family so that we are ever more worthy of his beneficence and his blessing.

Ich freue mich Deines gegenwärtigen Wohlseins um so mehr, weil ich voraussetzte, daß Du dabei hauptsächlich eine vergnügte Zukunft beabsichtigest. Dies ist auch mein tägliches Bitten zu dem lieben Gott, daß er mich und die Meinigen erleuchte u. stärke, damit wir seines Wohlgefallens u. seines Segens immer würdiger werden. [Dok 253]

Without saying it directly, Schubert's father places the blame for Schubert's illness squarely on his son's lifestyle – not unreasonably, we 21st century moralists probably think. This is surely an example of the 'blame from others' Schubert spoke about in his March letter to Kupelwieser. The fatherly guidance is here present in that Schubert's father 'assumes' that he intends to lead a 'happy life', the latter being religious code for a pious and moral life. We should read 'assume' in this context as being closer to 'expect' in meaning.

Sometime in August Schubert wrote to Schwind, confirming his current health. His happiness would be complete, however, if only his Vienna friends could be with him:

I am still, thank God, healthy and would be very happy here if only you, Schober and Kupelwieser were with me, but I sense despite the known attracting star sometimes a damn longing for Vienna. At the end of September I hope to see you again.

Ich bin noch immer Gottlob gesund u. würde mich hier recht wohl befinden, hätt’ ich Dich, Schober u. Kupelwieser bey mir, so aber verspüre ich trotz des anziehenden bewußten Sternes manchmahl eine verfluchte Sehnsucht nach Wien. Mit Ende Septemb. hoffe ich Dich wieder zu sehn.[Dok 255]

The reader will be immediately aware from the odd translation of trotz des anziehenden bewußten Sternes as 'despite the known attracting star' that neither your translator or anyone else has any idea what this means. In his notes on this passage, Deutsch guesses that it is a reference to the attractions of Caroline, but admits that 'all speculations are pointless'. We frequently encounter expressions such as this one in letters between the friends – fully comprehensible only to those who were part of their day-to-day banter. [But see update 03.09.2018.]

When did Schubert leave Zseliz in 1824?

We noted Schubert's conviction, in August 1824, that he hoped to return to Vienna around the end of September. This seems to contradict Schönstein's belief thirty years later that it was planned that Schubert should stay with the Esterházys until November. Schönstein tells us in his memoir that Schubert left Zseliz prematurely with him at the beginning of September, believing he had been poisoned by something. [Erinn 118]

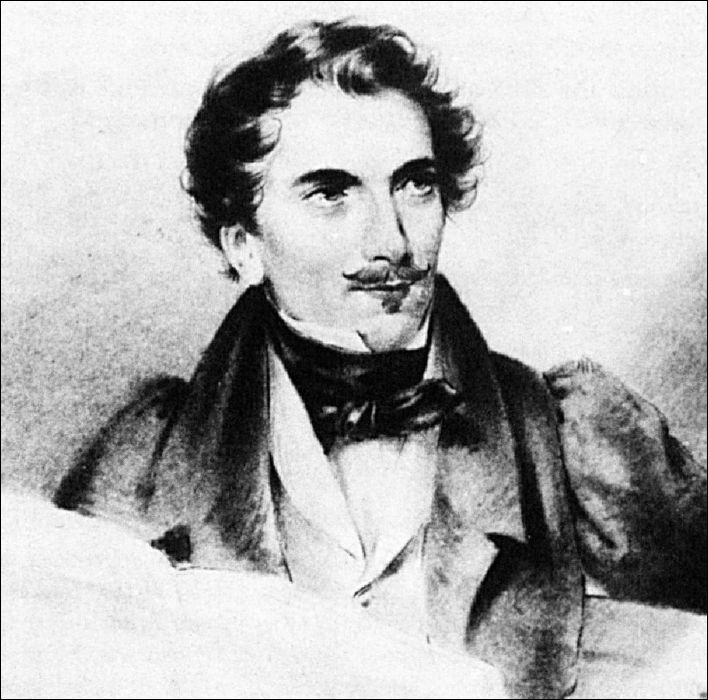

Karl Freiherr von Schönstein, watercolour by Josef Teltscher, c. end of the 1820s. Image: Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, I.N. 133.942/42 in [Steblin 93 34]

Schönstein's memory is not quite trustworthy on this point, since he cannot remember the year in question and he dates their journey back to Vienna as taking place at the beginning of September. In his memoirs he says nothing of the bitter cold that was such a feature of the letter he wrote to Count Esterházy, cold which would have been surprising in early September and a very memorable feature of the journey.

It also seems unlikely that Schubert had a particular fear of poisoning – we would have certainly heard of this strange hypochondria from someone else in his circle. Puzzling, too, is why Schubert in his poisoned state would risk a two-day journey back to Vienna, when all the medical care he would have needed was available in Zseliz.

We are dealing here with that phenomen known so well to Schubert research, eyewitnesses fantasising thirty or more years after the fact (Schönstein was writing in 1857). We therefore have to be sceptical of the abruptly premature return described in so many accounts of Schubert's Zseliz stay.

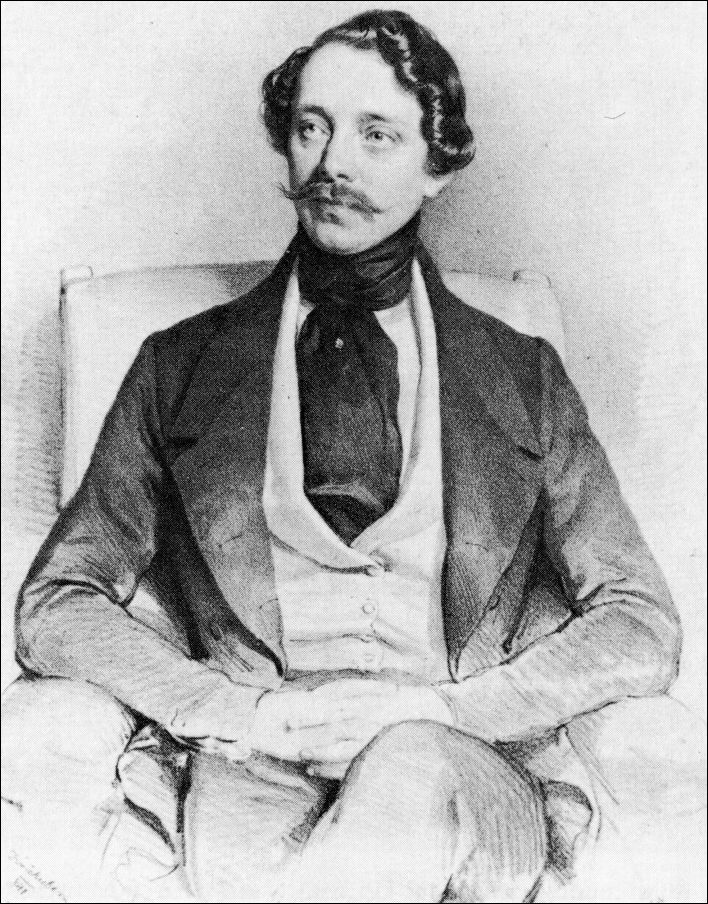

Karl Freiherr von Schönstein, lithograph by Joseph Kriehuber, ND. Image: Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien.

Fortunately, the letter written by Schönstein to Johann Esterházy a few days after the journey provides us with clear documentary evidence: Schubert left Zseliz with Schönstein on 16 October 1824 and arrived in Vienna on Sunday 17 October at around four in the afternoon. The letter makes no mention of Schubert's departure being in any way premature and no mention of Schubert's imaginary poisoned state.[Dok 262f 20 October 1824.]

That may have been the physical end of Schubert's stay in Zseliz in 1824 but one cord still bound him: Countess Caroline Esterházy.

Caroline: the enigma

Let's spit it out bluntly – we can quibble later: the great highlight of this stay in Zseliz for him was the presence of Countess Caroline. In our dealings with the Schubert biography we have had to unpick many knotty conundrums, but Countess Caroline – her nature, her biography and her relationship with Schubert – is one of the knottier ones.

On the surface, a relationship between Caroline, the 19-year-old Esterházy countess and the penniless, short, fat, unimposing, syphilitic, low-born underling Schubert would be a joke; the idea of a romantic relationship between the two would be a huge joke; the idea of a friendship laughable. Yet some sort of a relationship is hinted at in several independent sources, the most tantalising of which comes from the memory of a close eyewitness, a friend of both the Esterházys and Schubert, Baron Schönstein, as opposed to the second and third hand gossip among the Schubert circles. Schönstein tells us that:

The family Esterházy rapidly recognised the musically creative riches that Schubert possessed; he became a favourite of the family, remained during the winter as their music master at home and accompanied the family in later summers on their country estate in Hungary. He was frequently in the Esterházy home right up to his death.

A love affair with a servant, which Schubert began soon after his entry among the Esterházys gave way in turn to the more poetic flame which rose inside him for the younger daughter of the family. This passion burned inside him right until his end.

Welch musikalisch-schöpferischer Reichtum in Schubert lag, erkannte man bald im Hause Esterházy; er wurde ein Liebling der Familie, blieb auch über Winter in Wien Musikmeister im Hause und begleitete die Familie auch spätere Sommer hindurch auf das genannte Landgut in Ungarn. Er war überhaupt bis zu seinem Tode viel im Hause des Grafen Esterházy.

Ein Liebesverhältnis mit einer Dienerin, welches Schubert in diesem Hause bald nach seinem Eintritt in dasselbe anknüpfte, wich in der Folge einer poetischeren Flamme, welche für die jüngere Tochter des Hauses, Komtesse Karoline, in seinem Inneren emporschlug. Dieselbe loderte fort bis an sein Ende. [Erinn 116]

Despite all our reservations about the quality of Schönstein's memories, his explicit remark that Schubert's passion for Caroline 'burned inside him right until his end' makes it clear that his passion did not end on leaving Zseliz in 1824. To that we must add Schönstein's other remark, that Schubert 'was frequently in the Esterházy home right up to his death'. Whatever the relationship between Caroline and Schubert, it was certainly not a holiday romance.

Caroline esteemed his talent very highly, but did not return this love, perhaps she did not realise the degree to which it existed. I say 'the degree', because that he loved her must have been clear to her from a remark of Schubert's – his only expression [of his love] in words. When she once jokingly teased Schubert that he had never dedicated a piece of his to her he responded: 'Why do that? Everything is dedicated to you anyway.' The dedication of Opus 103 to her was done by Diabelli after Schubert's death.

Karoline schätzte ihn und sein Talent sehr hoch, erwiderte jedoch diese Liebe nicht, vielleicht ahnte sie dieselbe auch nicht einmal in dem Grade, als sie vorhanden war. Ich sage, {in dem Grade}, denn {daß} er sie liebe, mußte ihr durch eine Äußerung Schuberts – die einzige Erklärung in Worten – klargeworden sein. Als sie nämlich einst Schubert im Scherz vorgeworfen, er habe ihr noch gar kein Musikstück dediziert, erwiderte jener: »Wozu denn, es ist Ihnen ja ohnehin alles gewidmet.« Die Dedikation des Opus 103 erfolgte erst nach Schuberts Tod durch Diabelli. [Erinn 116]

Although Schönstein's account was written in 1857, almost thirty years after Schubert's death, his observations in this matter are credible on the whole: he knew everyone concerned intimately and was a close party to all these events. Nor, unlike some Schubert memorialists, does he have the slightest need to inflate the closeness of his relationship with Schubert. He only errs in stating that the dedication of the Fantasia in F-minor for four hands, D 940, was done by Diabelli – it was done by Schubert in April 1828 in his own hand.

From that Esterházy song quartet I am now the only one still living. The Countess outlived her husband and both daughters.

Von jenem Esterhäzyschen Gesangsquartett bin nur ich mehr am Leben. Die Gräfin überlebte den Gatten und die beiden Töchter. [Erinn 119]

We can take Schubert's adoration for Caroline as given, therefore, but whether the same confidence applies to the fact that, according to Schönstein, it was apparently not reciprocated is another question. At least for the moment we have to follow our instincts and agree with Schönstein, for no one has ever found the slightest documentary evidence of such a reciprocation – no billet-doux, no hasty note, not even a post-it sticker from her.

Who was this Countess Caroline, who captured Schubert's heart? To answer such tricky questions we have the indefatigable Rita Steblin, who in 1993 and 1994 published research that went some way to answering this question. One of Steblin's key research interests has been the illumination of the role of the women in Schubert's life and circle, a subject largely neglected by the mainstream of Schubert research. This neglect was particularly obvious in respect of Caroline.

Caroline: dim-witted juvenile?

On this website we have often expressed the greatest respect for the monumental contribution made by the Austrian musicologist Otto Deutsch to Schubert studies. In the case of Countess Caroline, however, even this Homer nods.

As Steblin shows, Deutsch had the fixed idea that Therese Grob, Schubert's passion (we are told) from around 1815, was the love of his life and that no other woman could have entered Schubert's sealed heart. As a result, according to Steblin, Deutsch downgraded the role of all the other females whose names surface in the Schubert biography.

This tunnel vision particularly affected his understanding of the relationship between Caroline and Schubert. Instead of being astonished, as we are, at Schubert's seemingly great love for her despite the immense social gap between them, he downgrades Caroline dismissively as merely a Backfisch, a 'vapid teenage girl' in Schubert's life:

Schubert's easy-going tolerance caused him to put up with his friends' mockery over the supposed love for Countess Caroline Esterházy – a harmless vapid teenage girl to whom he had given piano lessons in Zseliz – for so long until in the end they entirely believed it and the fable of the proud daughter of a count who disdained the master [musician] and of Schubert's realistic resignation was passed on to posterity in all seriousness.

Schubert hatte sich in seiner Gutmütigkeit so lange von seinen Freunden mit der vermeintlichen Liebe zur Komtesse Karoline Esterházy, einem harmlosen Backfisch, dem er in Zeliz Klavierunterricht erteilte, necken lassen, bis sie fest daran glaubten und die Mär von dem stolzen Grafentöchterlein, das den Meister verschmähte, und von Schuberts ‘realistischer’ Resignation mit vollem Ernste der Nachwelt überlieferten. [Steblin 93 22]

In everything he wrote, Deutsch stacked up the derision for Caroline. In Zseliz in 1818 she was 13 years old, ' unscheinbar und scheu', 'unprepossessing and shy', whereas her sister Marie, 17, was 'hübsch und geistreich', 'pretty and clever' and more musical. [Dok 68]

In his comments on Caroline on Schubert's second stay in Zseliz in 1824, Deutsch has even more invective for her. In marked contrast to her sister Marie, Caroline was

now grown up and nearly 20 years old, but had remained a child. So much so that even when she was thirty her mother sent her a hoop game.

[Sie] war nun auch herangewachsen und fast 20 Jahre alt, aber ein Kind geblieben. Sie blieb es so sehr, daß ihre Mutter sie Reifenspielen schickte, als sie schon dreißig geworden war. [Dok 251]

Caroline: sensitive musician

On the basis of music scores in Caroline's possession Steblin was able to show that Caroline was no half-wit girl but an extremely competent pianist. Whereas her older sister Marie had a beautiful voice and preferred to sing, it was in fact Caroline who was the great pianist in the family.

Steblin's careful work leads us to a new appreciation of the relationship between Caroline and Schubert. In Therese Grob, Schubert had found a girl with a beautiful voice but who was no musician; the musical relationship with the Grobs was with Therese's brother Heinrich. In Pepi Pöcklhofer he found an understanding ear, but not – so it seems – a musical one. In Caroline he found a woman – herself neither composer nor instrumental virtuoso – but someone who could at least share in his musical world.

In contrast to Deutsch's dismissive view, Schubert's love for her – we can believe Schönstein – was intense and on a level that exceeded that of any of the other women we know about.

All but the most consequential women are difficult subjects for the biographer. Up until recently very few females left anything of a footprint in the historical record. There may be a birth, marriage and death record; some records may cluster around a widow and her will; from the well-off there may be a portrait or two.

But as so often in Schubert studies, the critical thing is not what we know, but what we don't know. A substantial lacuna here is the relationship between Schubert, the Esterházy family, the girls in particular and Caroline in particular. As we have already noted, Schönstein, who as a close friend of the family and a friend of Schubert should really know, tells us that Schubert was not just the music master at Zseliz but also gave music lessons to the Esterházys at their home in Vienna. Schubert's contact with Caroline went far beyond the 1824 Zseliz visit.

We know this with certainty from an entry made by Eduard Bauernfeld in his diary in February 1828. Our certainty is justified, since not only was Bauernfeld one of those closest to Schubert at that time, his entry was made contemporaneously and is not some vague memory thirty years after the fact. He tells us:

Schubert seems to be seriously in love with Countess E[sterházy]. I like that in him. He is giving her lessons.

Schubert scheint im Ernst in die Comtesse E. verliebt. Mir gefällt das von ihm. Er gibt ihr Lektion. [Steblin 93 24]

What exactly was it about Schubert that Bauernfeld 'liked in him'? I would suggest that it was the sheer chutzpah of the broke composer falling in love with a countess from an ancient family – a man who was so low down the scale that he 'didn't even have Viennese citizenship', as Steblin pointedly put it. [Steblin 93 ibid]

Now we are bubbling with questions, none of which we can answer: how often did Schubert go to the Esterházy residence for these lessons? When did the series of lessons begin, when did they stop? Were the lessons for both girls or just Caroline? How much was Schubert paid?

We have no idea – so let us move on to yet another conundrum, Caroline herself.

Caroline: the obscurity of a life

What we know of Caroline Esterházy's (1805-1851) life would occupy at most just a line or two on an otherwise blank sheet of paper, most of her existence passed in dark obscurity. She was born on 6 September 1805. She died, 45‑years‑old, on 14 March 1851 from an intestinal ailment.

A bright flare lit up the obscurity when, sometime before 1818, Franz Schubert began to give her and her older sister Marie music lessons. He spent the summers of 1818 and 1824 at Zseliz as music master and musical entertainer to the family.

It would be surprising if the lessons in Vienna had not continued, possibly until the year of Schubert's death, 1828, a year in which he dedicated his wonderful four-handed Fantasia in F-minor for four hands D 940 to her. In this respect we can take Baron Schönstein's account from his memoir of Schubert at face value: that Schubert was a 'favourite' of the Esterházy family, had been a frequent presence at their home in Vienna, as well as spending two summers with them in Zseliz.

We should not assume that Caroline's teasing conversation about dedicating a piece to her took place at Zseliz – Schönstein does not say that. It would make more sense that if such a conversation took place – and the conversation doesn't feel to be invented – that it took place much closer to or immediately before April 1828 when Schubert dedicated the Fantasia to her. That dedication would have been a fitting response to that tease. As usual, we do not know.

With Schubert's passing the flare is extinguished and darkness once again shrouds Caroline's life. Without that flare Caroline would today just be one of the millions of names in the outer obscurities of the historical record, just as so many of the players in Schubert's circle are known today only because his bright flare illuminated some moment in their lives.

Caroline: music tutors

The only other thing we know about that obscure period in Caroline's life is that in 1838 (once, at least) a certain Joseph Edmund Petzina (1777-1862) was music master in Zseliz. He was music tutor to Caroline alone, since Marie, Caroline's sister, had married on 13 November 1827 and moved away from Zseliz; she had died on 30 September 1837, 34 years old; their father, Count Johann Esterházy had died on 21 August 1834, 58 years old. By this time, therefore, Zseliz was not the happy family country house that Schubert had known.

Petzina had been the music tutor to Count August von Breunner-Enkevoirth, who had been Marie's husband. Marie having died in September 1837, perhaps Petzina was transferred to Caroline's service for 1838. The one certain thing that we can take from Petzina's employment with Caroline is that she was certainly a competent musician – we possess two of the three albums of Petzina's compositions that he wrote for her and dedicated to her, dated October and December of 1838. [Weinmann 354f]

We cannot exclude the presence of other tutors for Caroline, either before or after Petzina in 1838, but in these situations of frustrating ignorance in Schubert studies the only solution is to move on.

Portrait of a marriage

Caroline kept the noiseless tenor of her way until 1844, that is, when we read that she married Karl Graf Folliot de Crenneville (1811-1873) on 8 May 1844 at Pressburg (now Bratislava). Karl was 33-years old; she was biologically 38-years-old – an unusual age difference because, of course, traditionally the groom is supposed to be older than the bride.

Never mind: the difference was cleared up by faking Caroline's certificate of baptism: on this she was – somewhat absurdly – given the same birthdate as the bridegroom: 28 March 1811. Her real birthdate was 6 September 1805

The incorrect date is still propagated in many accounts of her, even on the Esterházy website, so that if you are one of the very few who have ever wondered, lips pursed, about the immortal Franz Schubert giving a 7-year-old music lessons in 1818 and getting the hots for a 13-year-old in 1824 – well, there's your answer.

Caroline died seven years after her wedding, on 14 March 1851. Until her death she continued to use the surname de Crenneville. Two years after her death we learn that widower Karl married the thirty-two year-old Anna Lazansky von Bukowa (1821-1896) on 5 April 1853, and that the pair would have two children, one of whom survived.

Thanks to Steblin's detailed research on the documentary record, namely the archive of Karl's brother Franz Folliot de Crenneville (1815-1888) in the Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv in Vienna, we can shine a partial light on Caroline's life as a married woman.

It was not a happy marriage. It was effectively over only a few months after it began, but continued without divorce until Caroline's death. In other words the union was not just bad, it was irretrievably bad almost from the start.

Those cruel hearted ones who enjoy the entertainment of watching someone else's marriage break up will agree that much of the fun comes from observing the opposing camps blackening the other party's character – so much so that in the end both parties emerge with their reputations ruined.

So it was with Karl and Caroline. Steblin's paper contains much detailed commentary from the letters of Karl's brother Franz and Franz's fiancée, Herminie Chotek de Chotkowa et Wognin (1815-1882). Franz and Herminie married on 14 May 1844, a week after Karl and Caroline.

The prurient will have to make do here with the executive summary. If you want more you will have to go to Steblin's paper and work your way through the careful transcriptions of gossipy letters that wander in and out of French and German.

Of course, after a relationship breaks down, the spectators all assert, unisono, that the pair should never have married in the first place. Job's comforters the lot of 'em. It is no different with Caroline and Karl – and in their case the spectators are absolutely correct.

In the early discussions of the pairing, Caroline is described by Karl's side of the family as 'very inferior in every respect' and her mother even 'a little common', leading Steblin to surmise that this may have been just the characteristic that enabled their easy commerce with Franz Schubert, who was never really at ease in the presence of the great and the good, the 'stiff people'.

The reader may recall Schubert's verdict on his first visit to Zseliz in 1818 on Caroline's mother, the Countess Rosina: ' die Gräfin stolz, doch zarter fühlend', 'the Countess proud, though sensitive'. [Dok 67]

We do not feign surprise at hearing a daughter of one of the great Hungarian dynasties referred to as 'common' and her own daughter as 'inferior in every respect', but then, as now, the two families involved in a marriage have their own decided opinions.

There are some hints that Karl was socially uncomfortable. We read of the surprise expressed by his brother that he has attended dinners and even 'danced!!!'. However, whenever the pair were observed together, the early signs were that their relationship was good and promising for the future.

Karl was a major from a military family. Nothing we read leads us to think him musical except in the most superficial sense; it is also telling that none of our commentators on their union mentions music at all in connection with the musically gifted Caroline.

At first Karl and Caroline gave every sign of being a couple in love. Karl's brother Franz amuses us in a letter to his wife with a description of a scene that might have come straight out of a Jane Austen novel:

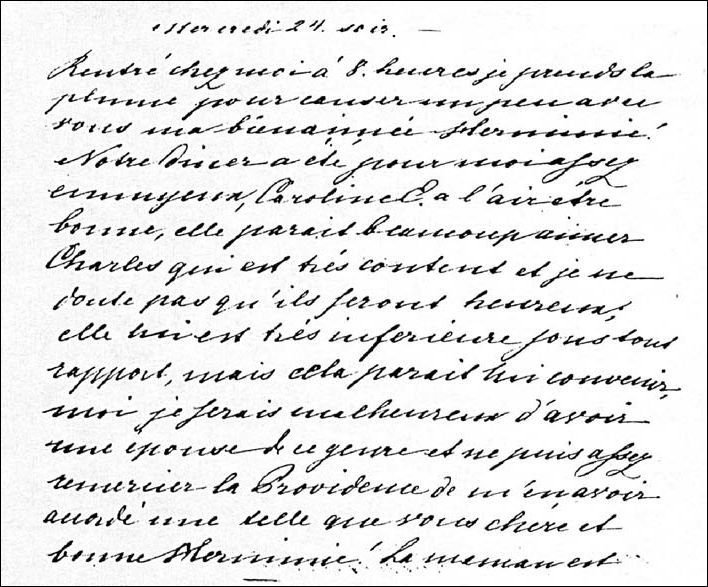

I recently accompanied my brother to the mesdames Esterházy, where I as a good brother made conversation with the good mother for more than an hour, – fortunately she did most of the talking – during which time the engaged couple chatted to each other in a distant part of the room. – Envy is not one of my many weaknesses – but watching this happy couple I felt quite lonely.

[J’]ai de nouveau accompagné mon frère chez Mes [mesdames] Esterházy, wo ich als guter Bruder mehr denn eine Stunde mit der Mutter Conversation machte, — zum Glücke bestritt sie den größten Theil — während das Brautpaar in einem entlegenen Theile des Zimmers plauderte. — Unter meinen zahlreichen Fehlern findet sich der Neid nicht vor — aber in Angesicht dieses glücklichen Paares fühlte ich mich recht einsam. [Steblin 94 20 – Letter 10. Franz à Herminie. [Vienne] Mardi 23. soir [April 1844]]

We read that Karl had wooed Caroline for 'four to five days' before proposing – who said, marry in haste, repent at leisure? Well, in their case the repentance seems to have come quickly.

A clause in the marriage contract stated that Karl and Caroline must reside in Zseliz. Countess Rosina, who was 60 at the time of the marriage (1784-1854) had been widowed in 1834, her daughter Marie (1802-1837) had died three years later in 1837. By the time of the marriage the third child, Albert (1813-1845), was on his last legs with tuberculosis in the Austrian Embassy in Paris. He would die there on 27 December 1845.

Letter of Franz Folliot de Crenneville to Herminie de Chotek. letter no. 12, 'Mercredi 24. soir [avril 1844].'. Image: Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv von Wien, Crenneville Karton 10. [Steblin 94 32]

It is understandable that the Countess in her old age wanted to keep her only surviving child near to her, but she thus created that horror scenario for all husbands (and many wives, too): living with the mother-in-law. In fact her old age would last another ten years: she died on 2 August 1854, her last three years were spent alone, since Caroline died in March 1851.

There are few husbands who can survive more than a few months living in the house of their mother-in-law; equally few mothers-in-law who can tolerate this uncouth brute violating their daughter under their roofs for more than a month or two. It is a truth universally acknowledged, as Miss Austen noted in another context.

It appears, too, that Karl had hoped for a rich wife. There were of course riches in the Esterházy family, but they were not destined for him. As a military man he had ended up at the time of his marriage as a 33 year old retired major with nothing to his name and an income of 600 florins a month – on which sum it was 'impossible to live'. Tell that to Schubert.

It seems, too, that Karl was an inadequate soldier, for he was demoted (or about to be demoted), a fact which probably led to his retirement from the army in 1842. Steblin suspects that this left Karl in the position of needing to find a wealthy wife, which in turn may explain the haste of the mere four or five days' courtship he went through.

We hear that the military man in him preferred giving orders, a habit that his new wife found tiresome. We remind ourselves at this point that Caroline is not the flexible young girl who might accept and understand such behaviour – on paper she had exactly the same age as her husband, 33, but in reality she had a physical and mental age of 39. One onlooker suggested that a younger girl might have put up with Karl and acquiesced in his ways.

Although we hinted earlier that he was not a very sociable figure, his sister-in-law Herminie wrote to his brother Franz describing a visit of Karl's to Korompa in early September 1844, during the time his marriage was falling apart:

Karl left us today by the earliest [postcoach] — he is going from here via Pressburg to Vienna. He appeared to me to have been very happy with his stay, yesterday the brothers took him hunting, then took him around the garden, theatre etc. all the sights —, then dinner — after dinner he had to marvel at the Monument, which he did with great good grace —, then pistol shooting — with the brothers — a promenade with Mother and Aunt, then a concert given by me and Jülliy, then a tête à tête with me during the Boston [a card game], we talked of everything possible, literature, music, art, travel, life, death, medicine, somnambulism, magnetism, spirits, ghosts, natural science, morals and religion! It was all a highly educational mixture but time passed quickly —, then dinner and a grande soirée until eleven o'clock. Karl said the most flattering things about Korompa, life here and about my family —, he liked my brothers particularly.

Carl hat uns heute mit dem frühesten verlaßen — er ist von hier über Pressbourg nach Wien. Er schien mir mit seinem séjour zufrieden, gestern führten ihn die Brüder auf die Jagd, dann machte ich ihm die honneurs vom Garten, Theater ec. ec. alle Merkwürdigkeiten —, dann diner — nach Tisch mußte er auch noch das Monument bewundern ce qu’il fit de fort bonne grace —, dann pistolen schießen — mit den Brüdern — promenade mit Mutter u. Tante, dann Concert von mir u. Jülliy, dann tête à tête mit mir während dem Boston, wir sprachen von Allen möglichen, Literatur, Musique, Kunst, Reisen, Leben, Sterben, Medizin, Somnambulisme, Magnetisme, Geister, Gespenster, Phisique, Moral u. Religion ! Es war eine höchst erbäuliche Macedoine das Ganze mais le temps passa assez bien —, dann gouter u. grande soirée bis 11 Uhr. Carl sagte mir die schmeichelhaftesten Dinge über Korompa das Leben hier, u. über meine Familie —, besonders gefielen ihm meine Brüder. [Steblin 94 23 – Letter 25. Herminie à Franz. Korompa 5. [September 1844]]

Even allowing for the fact that Herminie may be painting a flattering picture for his brother, this is not a description of an introverted, asocial person. It is not a description of a particularly profound person, either. During his stay she wisely kept off the subject of his marriage and his mother-in-law.

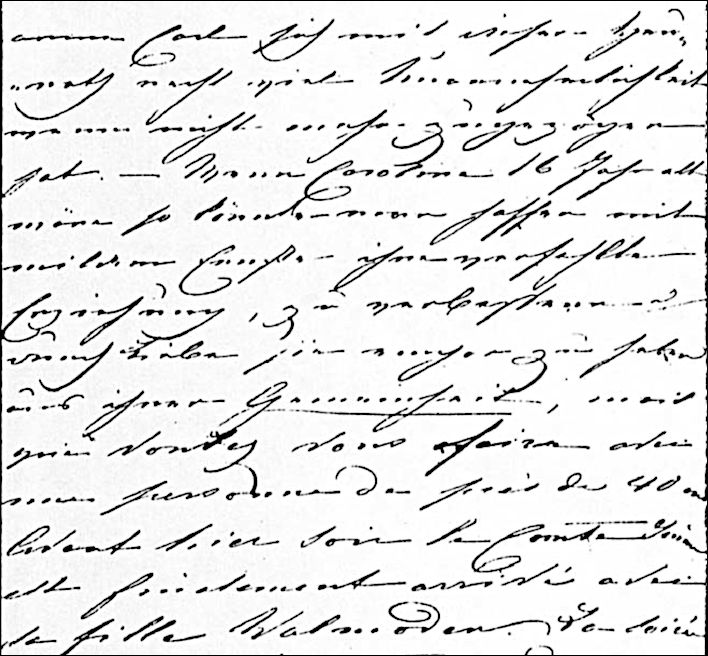

'I am sorry for Karl with all my heart', she concludes, 'this marriage was utterly foolish!':

Perhaps by separating from the mother, who has never kept her word and who reveals herself as what she has always been, vicious and common, the marriage would be better.

Peut-être qu’en se separant de la mère qui ne tient parole en rien et qui se montre telle qu’elle a toujours été méchante et comune, le ménage ira mieux. [Steblin 94 ibid]

Letter of Herminie Chotek-Crenneville to Franz Folliot de Crenneville. Letter no. 30, 'Korompa 12. [septembre 1844].' Image: Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv Wien, Crenneville Karton 8. [Steblin 94 33]

Only a few days after this, on 12 September, we hear in another letter from Herminie to Franz that Karl has left Zseliz, much to Herminie's relief. Caroline did not follow him, but stayed with Mama.

How can we prurient observers judge what is going on here, 174 years later? Perhaps the most balanced contemporary gossip comes from Henriette de Chotek (1787-1857), Herminie's mother and an almost exact contemporary of Caroline's mother, Rosina (1784-1854):

Here already everyone is talking of the separation of Karl from his wife; Rudolf Appony wrote from Paris describing it as a completely final matter. Many people blame her, but most people find him at fault. Perhaps he used an overly military tone with her and thus forfeited her love. In a happy marriage each party must anticipate the wishes of the other, neither must demand; otherwise trust and love are gone, and what remains is at the most an indifferent relationship, if namely one party decides to be a downtrodden victim.

Man spricht hier schon allgemein von der Trennung des Karl von seiner Frau ; Rudolf Appony hat es sogar von Paris als eine ganz ausgemachte Sache geschrieben. Viele Leute geben ihr, doch die meisten ihm Unrecht. Vielleicht hat er einen zu militärischen Ton gegen sie angenommen und dadurch ihre Liebe verwirkt. In einer glücklichen Ehe muß kein Theil herschen wollen. Jeder muß jeden Wunsch des Andern zuvorkommen, aber fodern darf es keiner ; sonst ist es aus mit Vertrauen und Liebe, und was übrig bleibt, ist höchstens ein leidliches Verhältniß, wenn nemlich der eine Theil sich entschließt, ein unterdrücktes Opfer zu sein. [Steblin 94 25f – Letter 32. Henriette de Chotek à sa fille Herminie. Korompa d. 11ten Octob 1844]

Henriette's opinions strike the twenty-first century reader as wise and balanced. She knew Karl well and intuitively suspected where the fault in his character might lie. Even discounting that fault, according to Henriette he should have known what he was getting himself into:

I'm really sorry to have to say this, but Karl in particular can not be absolved of the great injustice, having failed to declare immediately before the marriage that he did not want to live henceforth with his mother-in-law, since Countess Esterházy made it very clear in her first letter that she never wanted to be separated from her daughter.

Es ist mir sehr leid es sagen zu müßen, allein Carl kann von dem großen Unrecht nicht frei gesprochen werden, nicht gleich vor der Heurath erklärt zu haben daß er nicht für immer bei seiner Schw. Mutter établirt bleiben wolle da Gr. Esterházy in ihrem ersten Brief sehr deutlich sich aussprach sich nie von ihrer Tochter trennen zu wollen. [Steblin 94 26 – Letter 33. Henriette de Chotek à Herminie. Futtak den 18ten October 1844]

Karl post marriage

Karl left Zseliz for the peace and quiet of a botanic garden in St. Pölten, an undemanding post which he managed for the rest of his life.

On 5 April 1853 he married Anna Lazansky von Bukowa (1821-1896). He was 42, she 32. She seems to have been a compliant soul who bore him a son, Ludwig Folliot de Crenneville-Poutet (1864-1952), whose great age brings us into the modern era. She proved capable of putting up with Karl's grumbling and hypochondria. Whether this tedious affect was present during Caroline's time we do not know, but by the time of his second marriage it was in full flow.

Even Karl's mother despaired of him. The robust Judith Charlotte Victoire Poutet (1789-1887) would live to be 97 years old and outlive her son Karl by 14 years. She was no sentimentalist and had no time for malingerers: ten years after the debacle of Karl's marriage to Caroline she wrote of him (26 March 1854): 'Karl is my most disagreable correspondant … he is never content'. [Steblin 94 29 'Charles est le correspondant qui m’est le plus désagréable … il n’est jamais content'.]

Even his brother, who had largely taken his side in the conflict with Caroline, had to accept the oddness of his character:

Karl is certainly a thorough-going hypochondriac and depressive, who holds it against others that they are not. Anna is a gentle and long-suffering maid.

Carl ist schon ein gründlicher Hypokonder, Weltschmerzler, der Andern übelnimmt daß sie es nicht sind. Anna ist eine sanfte Magd u. Dulderin. [Steblin 94 29 – Letter 48. Franz à Herminie. [Vienne] 19.7.1861]

Karl's mother was even more cutting, telling Franz that Karl talks all the time of a stroke or of the danger of going blind, that he believes he is about to lose his arms, that he is suffering from gout – 'poor Anna', she adds.

Caroline: the last years

And what of Caroline, the heroine of the Zseliz stay in 1824? Her mother Rosina died 70 years old at Zseliz on 2 August 1854, that is, ten years after Caroline's marriage. Rosina died alone – such an irony, given how hard she had tried to keep Caroline alongside her. She had outlived them all, her husband and children now all dead, for Caroline died in Zseliz on 14 March 1851 of an intestinal disorder.

This excursus into the history of her unhappy marriage has taught us one thing above all: that Otto Deutsch's portrayal of the girly, half-baked nineteen year-old Caroline in Zseliz in 1824 is almost certainly a travesty. When we recall Henriette de Chotek's magisterial judgment upon the failure of that marriage we can only agree that, on the basis of all we know, Caroline bore herself in the manner of a strong, independently-minded woman in an age when that was a difficult thing to be.

Once she was in her marriage, the social pressure for deference and accommodation did not work on her. Her husband Karl does not impress us with any outstanding qualities: his military career was inglorious and nothing he did during or after the marriage – beyond tending plants in a botanic garden – merits our slightest attention. The hypochondria of his later life suggests that his earlier life was not without psychological disturbance. The only puzzle is why on earth Caroline married this dolt in the first place.

Silent witnesses

And that would be that, except for one remarkable fact.

Caroline was not just a strong, independently-minded woman, she appears to have been an extremely gifted and sensitive musician. Karl Crenneville may have affected some musical interest during the brief days of their courtship but he was light years behind her in musical skill and understanding.

We recall that for Karl, 'music' was merely one of the 14 subjects he covered in his evening conversation with Herminie during the card game in September 1844; for Caroline it was something she had studied for years at the side of one of the greatest of all musical talents.

Perhaps one day she sat at the same piano that she had shared with Schubert and played her new husband a piano sonata from the group of three great sonatas that Schubert wrote in the frantic months just before his death (D 958, 959, 960). What on earth would the Major make of that – a piece of music that lasted longer than all the 14 subjects he could talk about?

We now know that Caroline had an extensive collection of music scores, particularly of Schubert compositions, but also, for example, of Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Op. 111. By 1975 we knew of nine Schubert autographs that were in her collection as well as eight volumes of first and early editions of Schubert's four handed piano pieces (dating from December 1823 until March 1830) that have been in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek since 1945. In 1991 nine volumes of Schubert songs were found to have been in her collection. Most of the music is marked up in some way, often in Schubert's own hand.

Rita Steblin notes that the volumes we have are all numbered on the cover in such a way that we must conclude that what we have is only a small part of Caroline's collection: it appears she had a considerable music library.

The first thing that we can conclude is that this is not the collection of a sentimentalist, a mere collector or a musical magpie. The markings in the score indicate that this music was studied and played. It is hardly possible to avoid the conclusion that Caroline was not just an accomplished pianist, but an accomplished musician.

The second thing we can conclude is that this is not a collection that arose during a few weeks' instruction in Zseliz. It points with great clarity to what Schönstein hinted at and what we always suspected, that the musical studies between Schubert and Caroline continued over a much longer period. The printed versions of Schubert's four-handed piano pieces extend several years beyond his death.

The third thing we note is that, irrespective of that weasel word 'love', Schubert clearly had a great respect for Caroline's talent. The Beethoven Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111 (c. 1822), his last piano sonata, a difficult, intense and complex piece, a challenge for any concert pianist, was just the kind of thing that Schubert would have studied intently. The fact that we find it in Caroline's possession tells us how deep and how serious their studies were.

It seems incontrovertible that Schubert's lessons were not those that might be given to a vacuous girl – Deutsch's Backfish – in order to enable her to knock out something amusing for her dinner party guests. These lessons were joint voyages in musical understanding: the master leading and the pupil following in his wake, earning his respect. The fact that Schubert wrote so many four-handed pieces for her was not so that their 'hands could touch', as is so often fatuously asserted, but that he was playing with a worthy partner – otherwise he could have just scribbled down some simple tunes and let her work at them whilst he listened. Marie – also a fine pianist from what we know – with Caroline must have made a fine performing duo.

In reality, Schubert had found a soulmate.

The fourth thing we learn from Caroline's music collection comes from the bound albums of autograph scores. The song albums are bound in brown-yellow marbled paper covers and carry a rectangular red label with a gold border bearing a title and the initials 'C.G.C.' – presumably 'Caroline Gräfin Crenneville' (Caroline Countess Crenneville) in gold. The labels have been professionally produced.

The eight volumes of printed scores also have similar labels, the title pages are often signed by Caroline; the signatures seem to come from different times and – in contrast to the labels – are Esterházy, not Crenneville signatures. Beethoven's Piano Sonata is bound less sumptuously, is signed 'Caroline Esterházy' but has no label, possibly hinting at a slightly lesser reverence than that paid to Schubert's music.

Curating her Schubert

Caroline – who else? – labelled these albums sometime after her marriage. We have to ask: why then? Why then and not in the twenty intervening years that follow Zseliz?

Music album 13/VIII from the collection of Caroline de Crenneville (née Esterházy). Image: [Steblin 93 25]

Since she kept the surname Crenneville until her death, the labels could have been written any time in the seven years between 1844 and 1851. It is fair to assume that the bound albums were also created at this time, but it is not inconceivable that the albums had been created at an earlier time and merely labelled after 1844.

It is a remarkable fact, a quite astonishing fact, that we find Caroline curating her Schubert manuscripts at that particular moment in her life – perhaps in the first flush of happiness of her marriage, perhaps in the rancour of the years that followed. It might have been on the twentieth anniversary of that Zseliz summer, 1844, or even the twentieth anniversary of his death, 1848.

With this degree of piety all those years after his death, it is obvious that she could not have been indifferent on learning that he had died that November 1828. The music they played in Zseliz could not have been played by a cold, indifferent heart. He was more than a music tutor.

If Schubert had found a soulmate, so too had Caroline.

Schönstein assured us that Schubert's obvious love was not reciprocated by Caroline, but we have to ask ourselves, would he have known if it had been? She was a nineteen year old girl and quite capable of keeping a crush from her parents or her parents' friends, especially if, as seems to be the case here, the relationship was not physical but mental.

We scratch our heads in puzzlement: the nineteen your old girl – not unattractive, noble, moneyed, utterly eligible – waited 16 years before accepting a proposal. She was nearly forty when it finally happened, an astonishing age to marry. Can anyone believe that this most eligible girl never had any other suitors? If she had, she must have rejected them all – or, perhaps, wiser than Karl, they had rejected a life with the mother-in-law.

But nevertheless, the curation of these albums is undeniably an act of piety – of reverence, of recall, of memorialisation – of those days in Zseliz when the musical girl sat next to the musical genius and four hands moved as one.

Her music collection speaks as eloquently to us as any bundle of love letters bound in ribbon. She bound up and labelled that moment in her life: was it to close it, the end of an era, put it behind her and move on; or was it to piously memorialise it? She came back to that time at some moment after her marriage – perhaps she had never really left it. It is clear that she did not forget Schubert after his visit to Zseliz in 1824, nor after his death in 1828 nor ever until the creation of those precious albums. She has an edition of Die schöne Müllerin signed by Schönstein, with modifications and decorations in the music and with breathing marks.

The instant of every mark in that and all those other scores she would remember almost as if it were a photograph, the albums and their markings a memory of shared times in Zseliz and perhaps in Vienna later. They were love letters, unscented, which would call up sacred moments twenty years before; objects radiating the aura of the original (Walter Benjamin), the genius of the object, which stays attached, compared with the genius of place, which quickly evaporates.

And fatuous, dim, Major Crenneville would have had no idea of what Caroline had bound together here – probably only a musician would read these scores correctly and suspect their deeper message, a message that in its full import only Caroline and poor dead Schubert could understand.

We really do know next to nothing about those two.

Orthography

In this article Karoline Esterházy de Galántha (1805-1851) has generally been referred to as 'Caroline', which is the spelling she usually used herself. Where someone else has written 'Karoline', this has been left as such. Similarly, Mária Terezia Karoline Esterházy de Galántha (1802-1837) is called simply 'Marie'. Instead of the Hungarian form 'Roza' for Countess Roza Festetics von Tolna we have used the more usual form 'Rosina'. The reader will have to cope with 'Karl' and 'Carl' and occasional bursts of Hungarian.

Sources

All translations ©FoS.

| Dok | Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Dokumente Seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. [DE] |

| Erinn | —, ed. Schubert: Die Erinnerungen Seiner Freunde. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1997. [DE] |

| Steblin 93 | Steblin, Rita. 'Neue Forschungsaspekte zu Caroline Esterházy' in Schubert durch die Brille 11, June 1993, p. 21-34. [DE] |

| Steblin 94 | —. 'Le mariage malheureux de Caroline Esterházy. Une histoire authentique, telle que'elle est retracée dans les lettres de la famille Crenneville.' Cahiers F. Schubert, vol. 5, 1994, pp. 17–34. [FR] The author would like to express his gratitude to Dr Rita Steblin and Professer Xavier Hascher, Université de Strasbourg, for their prompt assistance in accessing this article. |

| Weinmann | Weinmann, Alexander. 'Father Leopold Puschl – Schubert at Zseliz' in Badura-Skoda, Eva and Peter Branscombe, Schubert Studies: Problems of Style and Chronology, Cambridge University Press, 1982, p. 347-356. [EN] |

Update 02.09.2018

- Added two paragraphs discussing a diary entry by Eduard Bauernfeld in February 1828 mentioning Schubert's love for Caroline.

- Corrected some minor typographical errors.

- Changed the forename of Caroline's mother from the Hungarian form 'Roza' [Festetics von Tolna] to the more usual 'Rosina'.

- The Fantasia in F-minor for four hands D 940, the only work that Schubert ever dedicated to Caroline, was treated in a perfunctory way in this article. The article was already too long, but I hope to return to the subject some day. Whilst you are waiting, you may want to listen to it and make up your own mind about the relationship between Franz Schubert and Caroline Esterházy. Of the versions on YouTube, for my taste the performance to beat is still that of Alfred Brendel and Evelyne Crochet (in two parts), but a performance on a Conrad Graf 1826 fortepiano of 1826 by Jos van Immerseel and Claire Chevallier comes close. Chacun à son goût: the very variety of interpretations shows what a complex and subtle piece this is.

Update 03.09.2018

The attracting star

…so aber verspüre ich trotz des anziehenden bewußten Sternes manchmahl eine verfluchte Sehnsucht nach Wien.

In a recent email to me Dr Rita Steblin noted that she had somewhere read that 'the name "Esterhazy" suggests "star" (Stern)'.

Despite extensive searches in Esterházy and Hungarian sources I have found no evidence that the name of the house, first adopted by the ancestor Benedek Eszterhas (1508-1553) was in any way derived from the word 'star' or any of its variants in Hungarian (' csillag' etc). I won't bore you with all these dead ends – any well-disposed Hungarian speaker reading this can tell me better, if necessary.

You have to get up early in the morning to keep up with these clever boys from the Schottengymnasium (Schwind and Bauernfeld) – and let's not forget that poor Franz Schubert, who really only wanted to compose and make music, had a few years of Greek parsed into him in the Stadtkonvikt, too. My guess – and how can I prove this? – is that these clever boys were playing with Greek in order to obscure the object of Schubert's love.

The name 'Esterházy' would make the Greek scholars in the Schubert circle think of ἀστήρ, [aster], 'star'. It is then only a small step to ἀστέρας, [asteras], 'Star', used as a name or nickname in the famous/notorious epigram ascribed to Plato in the Greek Anthology (book 7, chapter 669):

ἀστέρας εἰσαθρεῖς ἀστήρ ἐμός. εἴθε γενοίμην

οὐρανός, ὡς πολλοῖς ὄμμασιν εἰς σὲ βλέπω.

Aster gazes at the stars, my star; would I were Heaven,

that I might gaze at thee with many eyes!

ἀστέρας and perhaps even more so ἀστέρας εἰσαθρεῖς, [asteras eisathreis], 'Aster, you look at… ', when spoken by a suitably inebriated Greek scholar in a Viennese accent in a coffee house, might sound quite close to 'Esterházy'.

Not only the sound but the context makes sense: Plato's epigram of lustful desire and distant longing perfectly fits the circumstances of Schubert's longing for Caroline, that distant star.

The epigram happens to be a favourite in the Figures of Speech canon. We dealt with it when Rupert Brooke, yet another smart-alec classicist, inserted a few words from the epigram into his poem Grantchester: εἴθε γενοίμην [οὐρανός], [eithe genoimen ouranos], 'Would I were [the sky]'. Whereas Brooke was longing for Grantchester, John Betjeman, who alluded to Brooke's poem in his own poem The Olympic Girl, had much less elevated longings: to be the racket pressed against the breast of a wonderful tennis-playing girl. ('Would I were ... An object fit to claim her look.').

The 'Schubert was gay' gang will be wetting themselves at the allusion to Plato's longing for the young man, Asteras. Forget it. The more delicate flowers who have translated this passage have often executed a fashionable gender change on the gorgeous Asteras: with one slash of the pen he becomes 'Stella' and thus anthology-safe.

Update 07.09.2018

Added some illustrations. For images of Zseliz see our article about Schubert's 1818 stay.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!