Franz Schubert below stairs

Richard Law, UTC 2018-07-08 16:22 Updated on UTC 2019-05-08

The inner Schubert

In the summer and autumn of 1818, that is, two hundred years ago, Franz Schubert spent four months (17 July to 19 November) as 'Music Master' with the Esterházy family on their country house in Zseliz 230 km due east from Vienna.

For the pedantic: Before 1918 Zseliz was in Hungary, from then until 1938 in Czechoslovakia, from 1938 to 1945 back in Hungary, after that in Czechoslovakia again until 1993, then after that in Slovakia, close to the Hungarian border. The current official language is Slovak, but in Schubert's time the inhabitants spoke Hungarian. Reflecting the changes down the years and the hang to phonetic spelling in foreign languages the name Zseliz occurs in many different variants. Mindful of the sanity of our readers we have converted all the variant spellings to a simple 'Zseliz' without any accents. The modern name is Želiezovce.

An aerial view of the the present day Zseliz country house before the completion of the rescue renovations after 2014. Image: History of town Želiezovce.

Those months are not very important musically. As far as we know, Schubert wrote only three songs during this time: Einsamkeit, 'Loneliness / Solitude' [Johann Mayrhofer (1787-1836), D 620, July], Der Blumenbrief, 'Flower letter' and Das Marienbild, 'Image of Mary' [both Aloys Schreiber (1763-1841), D 622, D 623, August].

But those four months are of immense importance for our understanding of Schubert himself, for during this time he was in correspondence with parents, siblings and friends. The letters which have survived from this correspondence provide our best insight into the personality of Schubert, the dynamics of his family and his relationship with his friends at that time.

Schubert was not a frequent writer of personal letters. We have a number of administrative letters he wrote which are interesting for the facts of his biography, but these are largely impersonal. Most of the time most of his friends were around him in Vienna, so no letters between them needed to be written. Nor was he a diarist: a very sparse early journal has survived and some other journal scraps from various times, but if only he had been a scribbling diarist like his later friends, the Hartmann brothers, what a treasure we would have had!

Schubert would go to Zseliz a second time six years later, from May to October 1824. We have a few letters from that time, but nothing like the volume or importance of the 1818 stay, so that is where we will focus our attention. There is plenty to focus on, too – we Schubert fans will chew over with relish every crumb that falls from this particular table.

You have been warned! Best lay down stocks now: water, a bottle or three of a reliable red, a mound of shavings of Bündnerfleisch and Sbrinz. You might even begin to enjoy this piece after a while.

The adventure

The 1818 stay – at least the first part of it – is marked by another factor: excitement. It was his first journey anywhere outside Vienna, his first real separation from family and friends. The two occasions he went to Zseliz were the only two occasions in his life when he went beyond the Austrian border (technically speaking, that is – in Zseliz he was still within the Austrian Empire).

His early letters from Zseliz bubble with an excitement that anyone will recognise in their own letters home written on their first journey without family. Perhaps only older people can remember this – in these days of worldwide email and messaging no one is ever away from anyone else for any time at all. Messaging and photographs flow continuously from the moment of departure to the moment of return. Let's hope that our modern readers can imagine the sense of distance, separation, detachment and the implicit possibility of homesickness that travel used to bring.

This level of excitement is important, for it caused Schubert – the great introvert – to communicate with his brothers and friends over matters about which we would otherwise know very little.

Zseliz and the Esterházy

The Count Esterházy at Zseliz was neither of the two Esterházys known to Haydn fans. Tracing the various branches of the immense family tree of the Esterházys requires steady nerves, lots of time and a pronouncing knowledge of Hungarian, Czech and Slovak – none of which we have.

Schubert's Esterházy was Count János Károly (Johann-Karl) Esterházy de Galántha (1775-1834). He was part of the 'Altsohl' branch of the family and did nothing whatever of interest to us, apart from hire Franz Schubert to amuse him and his family musically.

He married Countess Roza Festetics von Tolna (1784-1854) in 1802. They had three children: Marie-Therese (1802-1837), Karoline (1805-1851) and Albert János (1813-1845).

The house stands in a large botanic park. The three large oaks at the side of the house were planted by Johann-Karl Esterházy, Schubert's employer. Each one marks the birth of of one of his three children, Marie-Therese (1802), Karoline (1805) and Albert János (1813) Images: History of town Želiezovce.

Karoline's birth year is disputed: Otto Deutsch says 1805, others 1806, yet others 1811. [Dok 62] Since Deutsch visited Zseliz and went through their archives there personally we shall take his figure of 1805 to be the correct one. In comparison, a birth year of 1811 would make her seven when Schubert was in Zseliz the first time; on his second visit in 1824, when, according to many, he was lusting after her, she would have been a tasty thirteen year old, not a wrinkled nineteen year-old. The heroes of Figures of Speech do not get themselves involved in that kind of smut, so 1805 it is, then.

Whatever. None of these people did anything memorable with their lives either. None of them improved the lot of anyone's lives but their own.

So, to recap, when Schubert was in Zseliz in 1818 Marie was sixteen, Karoline thirteen and Albert five years old. Marie sang soprano, Karoline alto and both played the piano. Albert, his gender precluding an upbringing as a cultural performer, was left in peace to do what five-year-old boys boys do, perhaps pulling wings off flies. Deutsch reasonably assumes that Schubert had already been entertaining the Esterházys and giving the two girls piano lessons during the winter months they spent in Vienna. [Dok 62]

Their summer residence – no one willingly stayed in Vienna during the stuffy, stinking and dusty summer months unless they had to – was in Zseliz. The house was a relatively small affair but set in a very large park and extensive countryside. The house was built by the Esterházys around 1720, then rebuilt in 1787 as a single-storey with a large attic around a central, rectangular courtyard.

The adventure begins

Schubert applied for a passport to go to Zseliz on 7 July 1818.

In those days it was essential to obtain an offical document that would attest to your identity, state the destination and the reason for your journey and give the duration of your stay. Without this paper you might be treated at any point in your journey as a vagabond or fleeing criminal. Each town, county, state or country had border and customs posts, making it certain that you wouldn't get very far without valid papers.

7 July 1818

Schubert Franz

Rossau

in the Schoolhose No. 81

With his father Franz schoolteacher also there

(Place of birth) Thury

(State) Lower Austria

(Age) 21

(Character or Profession) Music Master with Johann Esterhazzy

(single) I (Travelling to) to Zselesz in Hungary

(Validity of the passport) 5 months

7. July 818

Schubert Franz

Rossau

im Schulhaus No. 81

Bei seinem Vater Franz Schullehrer allda

(Geburtsort) Thury

(Land) N.Oe

(Alter) 21

(Charakter oder Profession) Musikmeister bei Joh. Esterhazzy

(ledig) I (Reiset nach) nach Zselesz in Hungarn

(Dauer des Passes) 5 Monate

[Dok 52]

We should also draw attention to that necessity of all official documentation: the need to have a designated and officially comprehensible employment. For aristocrats, their feudal status was usually sufficient – no one would ask a count what his job was – but for everyone else some statement of position was essential. His occupation as an assistant schoolmaster, however lowly, was bureaucratically acceptable in a way that 'freelance composer' would not have been.

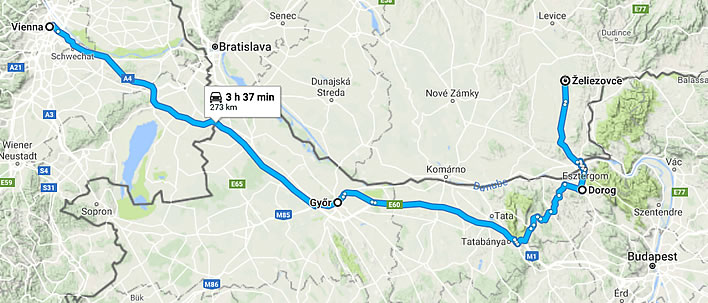

Vienna to Zseliz via the southern route between Vienna-Bratislava. The modern routes follow the old roads quite closely. Image: Google Maps.

According to Otto Deutsch [Dok 62], Schubert probably travelled to Zseliz alone by postcoach, a journey involving fourteen stations. Deutsch believes that the journey would have followed the old national road from Vienna that ran for most of its length south of the Danube in Hungary over Gygõr, heading towards Budapest before it turned north at Tatabánya to Dorog, crossing the Danube at Esztergom to enter present day Slovakia and go to Želiezovce, the modern name for Zseliz.

Google Maps tells us this route is 273 km on modern roads and would take about three and a half hours in a motor vehicle.

We don't really know: a northern route has been suggested that ran from Vienna, entered the modern Slovakia before Bratislava, from there to Hlohovec then Želiezovce. Your guess is as good as mine.

The exact time this journey would have taken him is a matter for conjecture, depending as it does so much on the condition of the roads. Stations would be around 20 km apart, a distance corresponding to about five hours of coach travel. The horses could no do more, they needed to be fed and watered and changed over; passengers also needed food, drink and comfort breaks. Overnight travel was out of the question on unlit roads of such poor quality.

We can guess that Schubert would have had to put up with the discomforts of the journey for several days, perhaps even a week. Such a journey was not cheap, but we can assume that the Count was paying for the transport of his music master from Vienna to his country retreat. Otto Deutsch estimates the cost as five florins (CM, ' Conventionsmünzen'), based on the number of stations. [Dok 64]

How much is that? It was two and a half times the amount needed to get into one of the exorbitantly priced Paganini concerts in Vienna (five florins WW) in 1828! In addition to that there would be the costs of food and lodging along the way. Coach travel was not for paupers – only the coming of the railways would change that.

The Esterházy family would have travelled in their own carriage independently of the postcoach, possibly with a coach containing a few important servants travelling with them.

The coach, its type and whether it was owned or hired, was just as much a status symbol then as the motor car is now. We only need a little thought to realise the great impetus there was for the development of the railways during the 19th century.

As for the experience of coach travel, the English art critic John Ruskin (1819-1900) had a talent for evoking romantic nostalgia in his Victorian readership, even while the iron horses and the satanic mills were under under construction. He could even do it for coach travel – and pan-European coach travel at that:

In the olden days of travelling, now to return no more, in which distance could not be vanquished without toil, but in which that toil was rewarded, partly by the power of deliberate survey of the countries through which the journey lay, and partly by the happiness of the evening hours, when, from the top of the last hill he had surmounted, the traveller beheld the quiet village where he was to rest, scattered among the meadows beside its valley stream; or, from the long-hoped-for turn in the dusty perspective of the causeway, saw, for the first time, the towers of some famed city, faint in the rays of sunset—hours of peaceful and thoughtful pleasure, for which the rush of the arrival in the railway station is perhaps not always, or to all men, an equivalent …

John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice. Volume the Second. The Sea-stories. London, 1853, Smith, Elder & Co., Chapter I, 'The Throne', §1.

Schubert's journey across the rural lowlands of Hungary probably had its attractions, but if he noticed them on that tedious journey he left us no record. It was the first major journey of his life – which may have lost its Ruskinian delights after the second day of rattling and bouncing along unmetalled roads.

And what did Schubert earn for his four months as music master for the Esterházys? Otto Deutsch estimates he was paid 75 florins (CM) per month, presumably food and board included. [Dok 64f] 300 florins (CM) for four months therefore, almost equal to the 800 florins (WW, Wiener Währung) Schubert received for his above-mentioned 1828 concert.

Postcard images of Zseliz. The exact date of the top image is unknown, but would be before the bottom image, the date of which is claimed to be 1942. On his visit to Zseliz in 1928, Otto Deutsch noted that the house was covered in wisteria. [Dok 62]

Zseliz castle 'before 1903'. Only the columns of the entrance have climbing plants. There is no sign of the extensive wisteria that would be there in 1928. Image Borovszky Samu.

The first letters home

Schubert's first letter from Zseliz that we know about was quite properly written to his parents. He wrote it around 1 August – the late date perhaps a hint at the length of time he had been travelling.

Unfortunately, that letter has shared the fate of so much of the documentary material around Schubert: it is now 'lost'. Perhaps the letter contained some remarks about the journey, it would be surprising if it didn't, but they are lost to us with the rest of the letter.

Once filial duty had been attended to, he wrote to his friends a few days later:

Zseliz, 3 August 1818: Schubert to Schober and the other friends

Best, Dearest Friends!

How could I forget you, you, who are everything to me! Spaun, Schober, Mayrhofer, Senn, how are you, are you well? I am really fine. I am living and composing like a god, as though preordained.

Liebste, theuerste Freunde!

Wie könnte ich euch vergessen, euch, die ihr mir alles seyd! Spaun, Schober, Mayrhofer, Senn wie geht es Euch, lebt ihr wohl? Ich befinde mich recht wohl. Ich lebe und componire wie ein Gott, als wenn es so seyn müßte.

[Dok 62]

Now free from the narrow bounds of the drudgery of his position as an assistant schoolmaster in his father's school, we take the last phrase as a cry of joy.

Mayrhofer's Einsamkeit is finished, and in my opinion the best I have done – for I was without worry though. I hope that you are all healthy and happy, as I am.

Mayrhofer's 'Einsamkeit' ist fertig, und wie ich glaube, so ist's mein Bestes, was ich gemacht habe, denn ich war ja ohne Sorge. Ich hoffe, daß ihr alle recht gesund und froh seyd, wie ich es bin.

[Dok 63]

We on this website are Schubert realists: Not everything he wrote was wonderful. When considering Schubert's song compositions, we have now and again expressed the incontrovertible opinion that the texts with which he worked were of very variable quality.

Einsamkeit: best left alone.

When the texts were of high quality, such as Goethe's Heidenröslein or Gretchen am Spinnrade or Nähe des Geliebten, or Stolberg's Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen, or Grillparzer's Ständchen, Schubert's talent lifts them to the level of the sublime.

Even with mediocre texts, such as Litaney auf das Fest aller Seelen Schubert was capable of bending a refractory text to his will.

However, it is a truth sadly not universally acknowledged, that Schubert's friends – Johann Mayrhofer (1787-1836) in particular – were on the whole incompetent poets, their output often juvenile, often mimetic rubbish. Mayrhofer's mind was anyway gloomy, disturbed and beclouded by hypochondria, as his later suicide would confirm. His writing is generally sentimental dross. My language shocks you? In which case consider only, that if it weren't for his association with Schubert, Mayrhofer would be consigned to literary oblivion.

Mayrhofer's Einsamkeit is not worth detailed interpretation. It is all of 96 lines long. Fischer-Dieskau and Moore take just short of a very long 18 minutes to get through it – some bits loud, some soft, some slow, some quick, some frisky, some dreary warbling. There is a proof to this pudding: the reader should name any Schubert song collection that includes Einsamkeit. I can't.

Mayrhofer's stanzas are organized into six blocks of sixteen lines. Each block is broken into two sub-blocks of eight lines. The first block opens with a 'Give me …!' statement; the rhyme scheme is four couplets: a-a-b-b-c-c-d-d. The second block of the pair is a mysterious construction which has two couplets e-e-f-f, then a four line structure: g-h-h-g. The first four of the six second blocks begin with the word Doch, 'but' or 'however'; the last two for some reason don't. Even with this simple couplet scheme the rhymes in both blocks frequently show signs of desperation: 'an-Felsenbahn', 'Düsterheit-hingestreut', 'Ruhm-um' – neither sound rhymes nor sight rhymes.

Unlike we Schubert realists, the erratic Schubert Song Companion twists and turns in an attempt square the circle of Schubert's rendering of Mayrhofer's dismal tosh, ending up with a curate's egg – some parts are excellent:

Einsamkeit should thus be regarded, not as the last solo cantata, but as the first song cycle. It is full of fine music, and is perfectly performable. Why then is it ignored? Primarily because of the abstract nature of the theme and the poverty of the text, which is Mayrhofer at his most mediocre. The ideas are too grand and impersonal for the particularity and sensuousness of Schubert's genius. Significantly, it is the scene-painting of the last verses, when the cuckoo calls from the peaceful thicket, that calls forth the best music of the work. Even so, the neglect of this song is not to be excused; it is much too fine, and too important as an expression of Schubert's art, to be ignored.

John Reed, The Schubert Song Companion, Manchester University Press, 1997. p. 212-214.

The text is irretrievably bad, the poetaster Mayrhofer at his awful worst; even Schubert cannot rescue this.

Finally, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (1925-2012), whose opinions about Schubert's vocal music are always informed and deserving of our attention, in Auf den Spuren der Schubert-Lieder, p. 129, made a sensitive defence of Schubert's assertion that his setting of Einsamkeit was 'the best I have done': critics of the setting do not recognise just how much 'new and exciting' music there is in the piece. That may well be, we grumpy ones reply, but it is only there to attempt to cope with what Fischer-Dieskau correctly identifies as the difficulties posed for Schubert by the 'extremely abtract hero' of Mayrhofer's text. Schubert's immense talent was wasted on Mayrhofer's incompetent tosh.

The chains clatter to the ground

Between all the polite formulations in Schubert's letter to his friends, something deeper emerges: ich war ja ohne Sorge, 'I was without worry though'.

Worry. We can imagine the grinding school duties, but also the worry over an uncertain career. Two years before, he had failed to gain a position as a music teacher in Laibach, and since then had given up applying, his wished for relationship with Therese Grob (1798-1875) had apparently also fizzled out with that rejection. She would marry someone else two years after.

A man such as Schubert with no fixed employment was unable to marry as a result of Franz II/I's piece of misguided social engineering, the Ehe-Consens-Gesetz, the 'Marriage Consent Law' of 1815. In essence, only upright citizens with good jobs could marry.

In addition there were the professional concerns: Franz was writing music like the devil but without any recognition apart from that of his friends. They really were a crucial part of Schubert's life. Otto Deutsch is astonished to note that the song Einsamkeit which Schubert mentions here was in fact the 339th song that he wrote. [Dok 63] He is twenty-one.

The tense of his phrase 'I was without worry though' (as opposed to 'I am without worry') associates the lack of worry with the composition of Einsamkeit– we begin to sense what guilt must have been seated on his shoulder, whispering in his ear during the composition of his songs: that futile, income-free activity of a man on whom a church mouse might look down. What would become of him? Was he on the right course?

It was easy during this time for his father to deploy the argument that his son needed a steady job, a steady income and future prospects – however meagre – never mind the need for a bureaucratically defensible post in the Austrian Empire of Paperwork. It might have seemed to Franz that he would be chained to schoolteaching for the rest of his days, just as his brothers Ignaz and Ferdinand were. His worries are patent, but for a brief moment they were out of his sight back in Vienna.

With the help of Franz Schober, Schubert had fled from the parental apartment above the school house in Himmelpfortgrund. He lived with the Schobers that first time from the late autumn of 1816 until the summer of 1817. He returned to teaching at the Himmelpfortgrund school from August to December 1817, then from January to July 1818 – that is, just before his time in Zseliz – he was teaching in his father's brand-new school in Rossau. Would he ever escape?

Now I am alive for once, thank God. It was overdue, otherwise I would have become a ruined musician.

Jetzt lebe ich einmal, Gott sey Dank, es war Zeit, sonst war' noch ein verdorbener Musikant aus mir geworden.

[Dok 63]

He had had a year of grinding nine-hour days under his father's yoke, teaching unruly and recalcitrant children to write neatly between two rules etc. The journey to distant Zseliz must have seemed to him as a redemption and even, from these remarks, as a period of healing. Can we imagine his feelings on that first day of the journey, as the post coach rumbled along, Vienna and all his woes receding behind him?

On his return to Vienna in November of 1818, he did not return to the school but moved into an apartment with Johann Mayrhofer, where he would stay until December 1820, that is, about two years. If nothing else, the stay in Zseliz had been the caesura he needed to complete the process of separation that he and Schober had started in 1816.

Michael Vogl, the lifeline

Schober, give my respects to Herr Vogl. I'll allow myself the freedom of writing to him myself soon. If you can, get him to say whether he would have the goodness to sing a song of mine – whichever one he wishes – in Kunz's concert in November.

Schober melde meine Verehrung bei Herrn Vogl, ich werde nächstens so frey seyn, auch Ihm zu schreiben. Wenn es seyn kann, so bringe Ihm bei, ob er nicht die Güte haben wollte, bei dem Kunzischen Concerte im November ein Lied von mir zu singen, welches er will.

[Dok 63]

Franz Schober had been the one who introduced Schubert to the opera singer Johann Michael Vogl (1768-1840). Vogl had an ego commensurate with his voice and it took some effort for Schober to bring him down from his empyrean height to meet the tiny, young, unknown composer Franz Schubert, the teaching assistant from a school in the teeming suburbs. Vogl finally met Schubert in Schober's apartment in the autumn of 1817. Schubert's respectful treatment of Vogl could not be more clearly expressed: 'I'll allow myself the freedom of writing to him myself soon'.

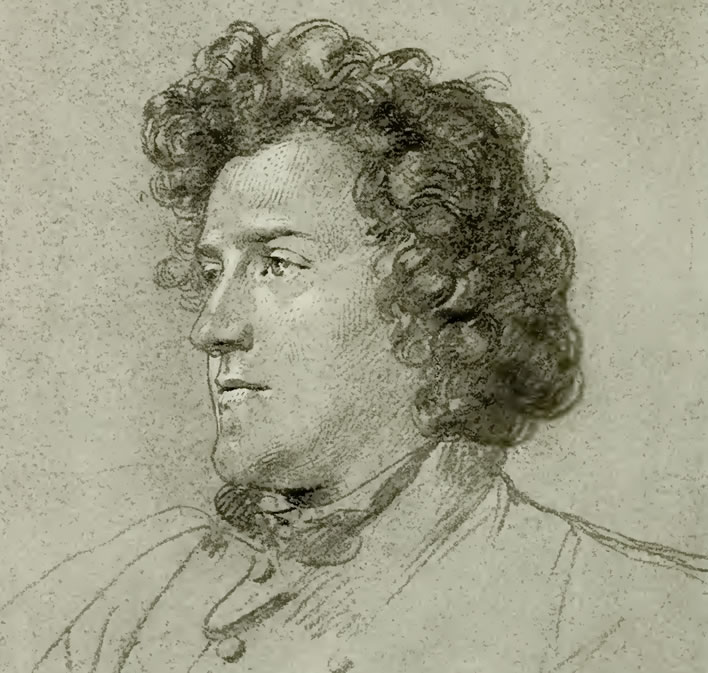

Leopold Kupelwieser, Portrait of Johann Michael Vogl, 1821.

The importance of having the renowned opera singer on Schubert's team can hardly be overstated. Vogl performed his songs to audiences that, at least in the first instance, were attracted by Vogl's considerable status. No one knew Schubert; everyone knew Vogl. Before Vogl arrived there was only silence in Schubert's compositions.

If we think back to our remarks about Schubert's lack of worry during the composition of Einsamkeit we may also be able to realise that the 338 songs that preceded it were composed mostly into silence, with scarcely the hope of a professional performance. After the tenth unperformed song a rational person might start to have some doubts whether composing songs was really what they should be doing in the snatched moments between schoolteaching; after the 338th even the workaholic Schubert may have begun to have doubts.

Let's not even discuss the unperformed symphonies, of which he wrote six – six! – finished ones in the years between 1811 (when he was 14) and 1818, before he went to Zseliz. That is why he talks of the immediate future he faced before his departure for Zseliz as being that of a 'ruined musician': six symphonies and 338 mostly groundbreaking songs. Silence.

Schober's acquisition of a professional performer to bring Schubert's work to a wider audience was therefore a masterstroke, we have to give the otherwise butterfly-brained Schober the credit for that and for having the social connections which accomplished it. Vogl's participation gave Schubert a reason to keep going.

Ultimately he would be called the Austrian Liederfürst, the 'Prince of Song', but that would be in ten years' time – he would be dead by then and free of all worry at last.

Give greetings to everyone I might know. Assure your mother and sister of my deepest reverence. Write to me very soon, every character from you is dear to me.

Your eternally loyal friend

Franz Schubert

Grüße mir alle möglichen Bekannten. An deine Mutter und Schwester meine tiefste Verehrung. Schreibt mir ja recht bald, jeder Buchstab von euch ist mir theuer.

Euer ewig treuer Freund

Franz Schubert.

[Dok 63]

Although not individually addressed to Schober – the letter was meant to be read by all the friends – it was sent first to him and the final greeting is aimed at Schober's widowed mother Katharina (1762-1833) and his sister Sophie (1795-1825). Sophie's elder sister, Ludovica von Schober (1790-1812) had died in tragic and scandalous circumstances six years previously.

Schober's (still) rich mother was the one supporting Schubert in his attempt to break free from the shackles of teaching in his father's school.

Joachim Reiber pointed out how often Schubert concluded the few letters we have of his with some form of a request to 'write to me very soon', such as we read here. Might we risk a guess that the recognition of his friends was extremely important for someone like Schubert, whose level of public recognition was so minimal? Reiber noted how precious these communications seem to be to Schubert: in a letter to his friends which we shall come across soon: 'with continual laughter and childish pleasure I read it in a neighbouring room' and concludes the same letter 'It is my dearest, happiest distraction to read your letters ten times over'. [Reiber 130]

Family matters

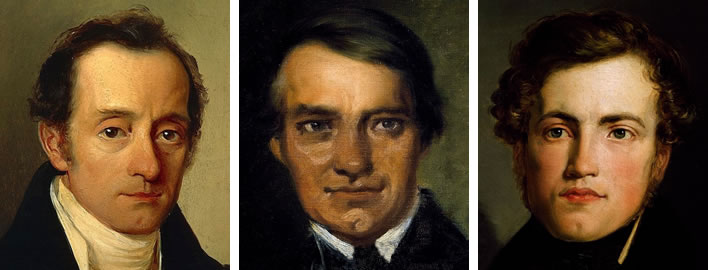

Franz Peter's three brothers (dates unknown). Left: Ignaz. Middle: Ferdinand, from an unfinished self-portrait – the 'Schubert dimple' was a challenge. Right: Karl. Image: Wien Museum, Schubert Geburtshaus, Nußdorfer Straße 54, 1090 Wien.

The next letter is not addressed to Franz Schubert in Zseliz at all, but nevertheless has something to say to us.

Vienna, 10 August 1818: Ignaz Schubert to Karl Schubert in Linz

Dearest beloved brother!

… From Franz I have to tell you that he wrote, according to which he is as well as a god must be and that he had ordered us to send his greetings to you as his twice-over brother as he himself put it. You will hear more details of him in Vienna …

Your loving brother

Ignaz Schubert

Herzallerliebster Bruder!

… Vom Franz muß ich Dir melden, daß er geschrieben hat, und daß er seines Schreibens nach sich wie ein Gott wohl befindet, und daß er besonders an Dich, als seinen zweifachen Bruder, wie er sich ausdrückt, seinen Gruß zu melden uns anbefohlen hat. Das Nähere von ihm wirst Du in Wien erfahren …

Dein Dich liebender Bruder

Ignaz Schubert.

[Dok 63]

It is now that we start to encounter the complex dynamic between Schubert, his parents and his brothers. Ignaz wrote in response to a letter sent by Franz to his parents and family. This may be the lost letter from around 1 August, or it may be another one about which we know nothing at all.

The lost letter sent to his parents would have probably included Ignaz as addressee, since he was living with them and teaching in the Rossau school. Ignaz (1785-1844) was the oldest brother of the four male survivors in the Schubert family. He lived through the loss of eight siblings until Ferdinand [Lukas] (1794-1859) came along. There was a flurry of successful childbearing in the next few years which brought us more brothers: [Franz] Karl (1795-1855) and Franz [Peter] (1797-1828), our composer.

Ignaz was nine years older than Ferdinand, ten years older than Karl and twelve years older than Franz – a solitary older figure with a cluster of much younger brothers.

Ignaz seems to have suffered as all first-born brothers do. As someone once put it: 'you make your mistakes with the first child'. Having no living siblings for a decade left him completely exposed to his father's wishes. His father wanted a schoolteacher in his own image – industrious, dutiful, respectable – and that is what he got. The cluster of the three younger brothers had a different fate: Ferdinand qualified as a teacher, but got a job at the Foundling School, which took him away from home; Karl was able to break away and become a landscape artist.

Karl was away in Linz when Schubert's letter to his parents arrived, hence the dutiful brother, Ignaz, wrote to him and passed on Franz's greetings. We have to be cautious when reading feelings into such letters. Ignaz's phrase sich wie ein Gott wohl befindet, 'he is as well as a god must be', which must have been something like a phrase Schubert used in his letter home, sounds like heavy irony coming from the homebound drudge Ignaz.

Schubert wrote something similar to his friends: Ich lebe und componire wie ein Gott, 'I am living and composing like a god', but more in contrast to the drudgery in the school at home rather than in any absolute sense.

We note that the curious phrase 'daß er besonders an Dich, als seinen zweifachen Bruder, wie er sich ausdrückt, seinen Gruß zu melden comes with zweifachen Bruder, 'twice-over' underlined, which Otto Deutsch takes as an allusion to the fact that Karl is not just Franz's physical brother, he is also his artistic brother. Ignaz, the prisoner rattling in his domestic chains, must have found the turn of phrase used by Franz almost a provocation: 'twice-over brother'. Ignaz's text is unmistakeably cool – perhaps even aggrieved – at this point: 'as he [Franz] himself put it'.

24 August 1818: Schubert to his brother Ferdinand

Dear brother Ferdinand!

… Things are not going well for you. I wish I could change places with you, so you could at least be happy for once. Every oppressive burden would be thrown off. Dear Brother, I wish it for you with all my heart.

Lieber Bruder Ferdinand!

… Dir geht es nicht gut, ich wollt, ich könnte mit Dir tauschen, so wärst Du einmahl froh. Jede drückende Last würdest Du abgeworfen finden. Lieber Bruder, ich wünscht' es Dir von Herzen.

[Dok 64]

At this time, unlike his brother Ignaz, Ferdinand had escaped the family house and was living and teaching in the orphanage in Vienna. I am not sure what in particular was not going well for Ferdinand at this time, but there seems to have been some turmoil in his professional life. From what follows the Dir geht es nicht gut it is clear that these are not health problems.

In the year of this letter Ferdinand had participated in the introduction of new teaching techniques by the Director of the orphanage, Franz Michael Vierthaler. Two years later, in 1820, Vierthaler's system was banned, being thought unsuitable for moral and religious education. Around this time Ferdinand, perhaps sensing the way the wind was blowing, had applied for a new post in Altlerchenfeld, which he was granted in March 1820.

… For your request I have one, too: Greet my dear parents, brothers and sisters, friends and acquaintances, not forgetting Karl in particular. Did he not mention me in his letter? ——— nudge or give my city friends a good poke so that they write to me.

… Für Deine Bitte hab ich auch eine: Grüße mir meine lieben Altern, Geschwister, Freunde und Bekannte, insonderheit Karln nicht zu vergessen. Gedachte er in seinem Briefe meiner nicht? ——— Stupfe oder laß meine Stadt-Freunde recht gewaltig stupfen, dß sie mir schreiben.

[Dok 64]

Once again we find Schubert explicitly referring to Karl, his 'twice-over brother', still in Linz and thus still outside the communication pathways. The term 'city friends' is justified, in the sense that Schubert's family base was in the Viennese Vororten, the 'suburbs', in Himmelpfortgrund and now Rossau. His new circle of friends were students and junior civil servants who lived or worked within the compass of the city of Vienna itself.

Once again, we find Franz pleading for his relatives and friends to write to him. The explanation for his need for communication comes immediately: his isolation and loneliness in Zseliz:

… As happy as I am, as healthy as I am, as good as the people here are, I am looking forward again and again to the moment when I hear: To Vienna, to Vienna! Yes, beloved Vienna, you contain the dearest and the most loved in your narrow confines and only a reunion, a heavenly reunion will still this longing.

… So wohl es mir geht, so gesund als ich bin, so gute Menschen als es hier gibt, so freue mich doch unendlich wieder auf den Augenblick, wo es heißen wird: Nach Wien, nach Wien! Ja, geliebtes Wien, Du schließest das Theuerste, das Liebste, in Deinen engen Raum, und nur Wiedersehen, himlisches Wiedersehen wird dieses Sehnen stillen.

[Dok 64]

Schubert's emotional outburst of homesickness for Vienna is remarkably revealing. The letter was written on 24 August 1818 and it seems that Schubert is getting heartily tired of life on a country estate after only a month there.

Mayrhofer's text Einsamkeit, 'loneliness / solitude' – if only in its title – can serve as a label for Schubert's entire experience in Zseliz. The poem ends with a romantic, moping evocation of woodland solitude – which might at first have seemed a blessing to Franz after the noisy turmoil of his father's school. But after his first couple of weeks at Zseliz we realise that Schubert has had enough of this intellectual and cultural solitude: 'To Vienna, to Vienna! … only a reunion, a heavenly reunion will still this longing'.

The Nonsense Society

Schubert obsessives will recall the sensation caused in Schubert scholarship by Rita Steblin's discoveries in 1998 of his participation in the Unsinnsgesellschaft, the Viennese 'Nonsense Society'. [Unsinn passim]

The society, a loose association of young men and women, was a phenomenon entirely in keeping with life under the heavy censorship strictures –the belljar– that had been held down over the Austrian Empire since at least the Jacobin Trials of 1796. It would last until 1848 (but return soon after).

The meetings were invitation-only for a very restricted circle of the trustworthy like-minded; anything that was written down was circulated in a handwritten form – readers may think of the Samizdat that circulated under the oppressive Communist regimes of eastern Europe – the principle was much the same.

The Nonsense Society was active between 1817 and 1818 as far as we can tell – it was a secret society, after all. Schubert was a very active participant. Some modern musicologists are rather snooty about the vulgar bufoonery of the Nonsense Society, thinking it unimportant in the life of the musician. They are mistaken. Although Schubert never mentions the society in the letters we have – one simply didn't do that under the belljar – we can scarcely doubt that he was thinking of the crazy antics of his friends in Vienna – the charades, the skits, the mockery, the persiflage – whilst he was stuck in the rural wilderness of Zseliz, teaching kids to play the piano and entertaining their noble parents.

Vienna, 27 August 1818: Father Schubert to his son Karl in Linz

Dear son!

… On the 10th I received another letter from your brother Franz; things are going so well for him that he considers himself very happy; he speaks in a very heartfelt manner, full of emotion and love; and sends greeting to each one of us by by name.

Lieber Sohn!

… Den 10. dies, erhielt ich wieder einen Brief von Deinem Bruder Franz; es geht ihm so gut, daß er sich sehr glücklich schätzt; er spricht in einem recht herzlichen Tone voll Empfindung und Liebe; und grüßt jedes von uns allen namentlich.

[Dok 65]

Schubert's father – educated in the Jesuit Gymnasium in Brünn – writes to his son Karl a letter of Jesuit precision that warmly notes that son Franz sent greetings 'to each one of us by by name'. Consider the precious formalism of the mind that feels it necessary to point out that everyone was greeted individually, 'by name'. Franz Schubert was raised by this man, although there are mitigating circumstances in his single-minded drive to get Franz the best musical education he could realistically have.

Franz's letter to his father seems to have been relentlessly positive – which, let's face it, is how wise children have written to their parents down the ages.

Franz Theodor Schubert. Unknown artist, unknown date.

Responding to the friends

8 September 1818: Schubert to Schober and the other friends

Dear Schober! Dear Spaun! Dear Mayrhofer! Dear Senn! Dear Streinsberg! Dear Wayß! Dear Weidlich!

… I cannot tell you just how endlessly delighted I was to receive your letter.I was at an ox and cattle auction when your letter was given to me. I opened it and let out a loud cry of joy when I saw the name Schober. With continual laughter and childish pleasure I read it in a neighbouring room. It seemed to me as though I held my dear friends themselves in my hand. Anyway, let me answer in an orderly fashion:

Lieber Schober! Lieber Spaun! Lieber Mayrhofer! Lieber Senn! Lieber Streinsberg! Lieber Wayß! Lieber Weidlich!

… Wie unendlich mich eure Briefe sammt u. sonders freuten, ist nicht auszusprechen! Ich war eben bey einer Ochsen- u. Kuh-Licitation, als man mir euren wohlbeleibten Brief überreichte. Ich brach ihn, u. ein lautes Freudengeschrey erhob ich, als ich den Nahmen Schober erblickte. Unter immerwährendem Gelächter u. kindischer Freude las ich sie in einem benachbarten Zimmer. Es war mir, als hielt ich meine theuren Freunde selbst in Händen. Doch ich will euch in aller Ordnung antworten:

[Dok 66]

A long letter full of riches for the Schubert fan, who will have no problem recognising the adressees Franz Schober, Joseph Spaun, Johann Mayrhofer and Johann Senn. The names Streinsberg, Wayß and Weidlich may cause some headscratching. In 1818 Schubert's friendships are still largely formed from his schooldays in the Vienna Stadtkonvikt– Spaun and Senn were among these, as were two of the three unknowns: Josef Ludwig von Streinsberg, who was there from 1808 to 1813; 'Wayß' is presumably Maximilian Weiße, who entered the school with Schubert in October 1808 and who was disciplined in 1810 for lack of application. [Dok 13] Weidlich is presumed to be Josef Weidlich from the Kremsmünster Stift, who seems to have no further significance for Schubert studies.

We note that all three of them, though largely off the radar for Schubert studies, were among the recipients of this very important letter. There is an awful lot we don't know about Franz Schubert and his life.

Joseph von Spaun by Leopold Kupelwieser, [ND, original now 'lost']

Johann Chrysostomus Senn by Leopold Kupelwieser, 1820.

Despite his homesickness and the trials of life in the country – an ox and cattle auction! – our Franz has clearly retained his sense of humour. The image of the dumpy city boy Schubert attending a cattle-market would have made his friends laugh out loud.

The first striking thing in this letter is Schubert's open favouritism for Franz Schober. He is not at all reticent about telling of his delight that Schober in particular had written to him. It may of course be that since Schober was a notoriously poor correspondent, a letter from him was a high honour indeed.

Franz von Schober by Leopold Kupelwieser, 1821.

Dear Schobert!

… I see this name transformation has stuck. So, dear Schober your letter was wonderful from beginning to end, but especially the last page. Yes, yes, that last page was delightful, you are a divine chap (in Swedish, naturally) and believe me, friend, you will not succumb: your sense for art is the purest, truest that is conceivable.

Lieber Schobert!

… Ich sehe denn schon, es bleibt bey dieser Nahmens Verwandlung. Also, lieber Schobert Dein Brief war mir von Anfang bis zum Ende sehr lieb u. kostbar, besonders aber das letzte Blatt. Ja ja das letzte Blatt setzte mich in volles Entzücken, du bist ein göttlicher Kerl (versteht sich im schwedischen) u. glaub es mir, Freund, du wirst nicht unterliegen, denn dein Sinn für die Kunst ist der reinste, wahrste, den man sich denken kann.

[Dok 66]

The special intimacy of the friendship between Franz Schubert and Franz Schober is exactly mirrored in the merging of their names, which seems to have first occurred shortly before the departure for Zseliz.

Schubert had lodged in rooms in the apartment of Schober's mother from the late autumn of 1816 until the summer of 1817. We can only speculate about the closeness of the relationship between Schubert and Schober: we explored this in our long piece about Schober nearly two years ago. Despite thousands of words on the subject we cannot claim to have resolved the conundrum. The creation of the 'Schobert' may have been the way that their friends dealt with their BFF status.

They are an odd couple. On one side we have the short, introverted, serious, taciturn, hard-up, workaholic musical genius whose interactions with the opposite sex (there was only one at that time, for all we know) seem to have been painfully shy; on the other the dilettante, extrovert, rich dabbler with the fine baritone speaking-voice which could spout forth a stream of seeming profundities without ever bothering to write them down. We have Schober the raffish seducer of women, the intellectual poseur who could drop names and terminology with the best of the bluffers; Schubert the very serious musician, his nature inimical to all bluffing.

Schober's long life is filled with half-cock ventures that never came to anything. His life left nothing of worth behind. Schubert's brief life is filled with artistic concentration and endless labour. His life left a treasure house of musical works behind. The two seem almost exactly complementary personalities, but that is no explanation at all.

What brought the serious, down-to-earth Schubert, Viennese through and through, to write such hyperbolic adoration about Schober? No idea.

Franz von Schober by Leopold Kupelwieser [ND], Wienmuseum, Austria. Torup Castle in Sweden is in the background, taken from a sketch of Schober's.

Schober was born and spent his early years in Sweden, hence Schubert's allusion to the parallels between the German word Kerl and the Swedish word karl, both of which carry connotations of a free, 'proper', robust, man. Students of medieval Scandinavian history will immediately recall the 'housecarls' that formed the king's bodyguard. Can we infer that Schober, the Mr Toad polymath among the friends, had made something of his Swedish origins – although there was no Swedish blood in his lineage at all? That he liked playing the exotic? Perhaps we are being unfair – unfair to Schober? Never!

… In Zseliz I have to do everything myself. Composer, editor, author and I don't know what else. Not a soul here has any idea of the Truth in art, at the most, now and again, when I am not mistaken, the Countess. I am alone with my loved one, and have to hide her in my room, in my piano, in my heart. Although this often makes me unhappy, so, on the other, it raises me up even more. Don't be afraid that I shall stay here longer than absolutely necessary.

… Denn in Zelez muß ich mir selbst alles sein. Compositeur, Redacteur, Autiteur u. was weiß ich noch alles. Für das Wahre der Kunst fühlt hier keine Seele, höchstens dann u. wann (wenn ich nicht irre) die Gräfinn. Ich bin also allein mit meiner Geliebten, u. muß sie in mein Zimmer, in mein Klavier, in meine Brust verbergen. Obwohl mich dieses öfters traurig macht, so hebt es mich auf der andern Seite desto mehr empor. Fürchtet euch also nicht, dß ich länger ausbleiben werde, als es die strengste Nothwendigkeit erfordert.

[Dok 66]

The Pressburger (Bratislavan) piano on which Schubert and the Esterhazys would have played. It is in the museum housed in the restored Bagolyvár, 'Owl's House', in which Schubert stayed on his 1824 visit. Image: Tip na výlet: Obec Želiezovce / Zdroj: TASR/Henrich Mišovič (2014).

The 'loved one' here refers to the Truth in art, a concept that was much discussed amongst the young men in the circles around Schubert at this time. In this context the concept is aimed in particular at Schober – being the kind of waffle with which he was clearly at ease. We read once again of Schubert's feelings of isolation in Zseliz and a resolution to leave and return to his beloved Vienna and the intellectual stimulation of his friends at the earliest opportunity. He has been there around six weeks by now.

Life below stairs

Schubert was the music master in Zseliz; one of the household retinue, who ate below stairs with the servants. He composed ditties for the family to sing and piano pieces to be played by the girls. The Esterházy family had no pretensions to musical sensibilities. Schubert had probably given the children lessons in Vienna. The cultured discussions in the circles of friends had no place here, in a country house in rural Hungary.

Now a description for everyone:

Our house is not one of the great ones, but very attractively built. It is surrounded by a very beautiful garden. I live in the 'Inspectorat'. It is fairly quiet, except for a flock of about 40 geese who sometimes cackle so loudly that you cannot hear yourself speak.

The people around me here are very good. There can be few courts the servants of which are so good together.

The Herr Inspektor, a Croatian, has a good opinion of his musical talent. He currently blows on the lute two 3/4 time German Dances with virtuosity. His son, studying philosophy, just arrived for the holiday, I hope to get to know him well. His [the Inspector's] wife is a woman like all the women who want to be called gracious.

Nun eine Beschreibung für alle:

Unser Schloß ist keins von den größten, aber sehr niedlich gebaut. Es wird von einem sehr schönen Garten umgeben. Ich wohne im Inspectorat. Es ist ziemlich ruhig, bis auf einige 40 Gänse die manchmahl so zusammenschnattern, dß man sein eigenes Wort nicht hören kann.

Die mich umgebenden Menschen sind durchaus gute. Selten wird irgend ein Grafen-Gesinde so gut zusammen gehen, wie dieses.

Der H. Inspector, ein Slavonier, ein braver Mann, bildet sich viel auf seine gehabten Musiktalente ein. Er bläst jetzt noch auf der Laute zwey 3/4 Deutsche mit Virtuosität. Sein Sohn ein studirender Philosoph, kam gerade auf die Ferien, ich wünsche ihn recht lieb zu gewinnen. Seine Frau ist eine Frau wie alle Frauen die gnädig heißen wollen.

[Dok 67]

Schubert's friends, who were familiar with his talent for mockery, would have much less difficulty decoding his descriptions of the people at Zseliz than we do. We have to rely on careful reading.

After laying the ground with some anodyne remarks about Zseliz itself, Schubert sets the tone with his sarcastic introduction to a theme, which in its entirety is almost a musical composition in itself: 'The people around me here are very good. There can be few courts the servants of which are so good together.' Reading this, his friends would be chuckling already. Readers who want to take this remark at its face value should perhaps spend a couple of weeks in Vienna sometime.

Then the first dissonant chord: 'The Herr Inspektor, a Croatian, has a good opinion of his musical talent.' The subtext seems to be that the young Schubert, the musical genius of his age, has been at the receiving end of a lecture on music from the 'Herr Inspector', to which Schubert has obviously had to listen with silent respect.

The concluding chord comes with a mocking semi-quote of musical ignorance from the opiner: 'He currently blows on the lute two 3/4 time German Dances with virtuosity'. We have all met people who confidently instruct others in matters about which they really know nothing – 'blows on the lute', indeed. Schubert's friends would have intuited exactly what had happened with 'Herr Inspektor'. They also knew what a short fuse Schubert had in musical matters: this example of Schubert's mastery of Wiener Schmäh, 'Viennese sarcastic mockery', would without doubt have made them all laugh out loud.

Having banged the chord of mockery at Herr Inspektor, Schubert now skewers Herr Inspektor's son with rapier irony: 'His son, studying philosophy, just arrived for the holiday, I hope to get to know him well.'

Schubert's friends would grasp immediately that the Schubert they knew would never be the submissive weed who 'hopes to get to know someone really well'.

Schubert is the 21 year old musical genius who was making his way in the hard world and who had slid out of academic studies voluntarily at the first opportunity near the end of his time in the Stadtkonvikt. Was he really going to be hanging on to the opinions of the student of philosophy anymore than he was those of the student's opinionated father who blows down lutes?

Schubert's circles of friends included musicians (composers and performers), pictorial artists, political and philosophical firebrands such as Senn and his friends, writers and worthy, sensitive, educated civil servants such as the Spauns. Schubert moved in the circles of the culture of the age. The legend is that whenever a new person was introduced to his circle, Schubert would ask Kann er was?, 'what can he do'.

The student of philosophy would have a mountain to climb to befriend Schubert and Schubert's friends would realise this immediately. They would also realise from 'I hope to get to know him well' that the son of Herr Inspektor, the student of philosophy, has so far snubbed or patronised the little music master with no university education to his name.

After demolishing the Herr Inspektor with mockery and his son with irony, Schubert turns to the demolition of his wife: 'a woman like all the women who want to be called gracious'. The direct translation of gnädig heißen wollen into modern English is not simple – even that modern guardian of the German language, the Duden, notes that the use of gnädig is oft ironisch, 'frequently ironic'. We might try a phrase such as 'wants to ingratiate herself with others', but why this should be a female characteristic is a mystery. It may be that another paraphrase may be more fitting: the woman is married to a man of low bureaucratic rank yet 'gives herself airs and graces'. Whatever it is, Schubert doesn't like it.

We learn about some more underlings:

The bursar quite fits his office, a man with exceptional insights into his pockets and purses. The doctor, really skilful, at 24 is ailing like an old lady. Too unnatural. The surgeon, whom I like the best, a respectable old man of 75, is always cheerful and happy. May God give everyone such a happy old age. The magistrate, a very natural, upright man. A companion of the Count, an old, merry chap and a solid musician, is often my companion.

The cook, the lady's maid, the chambermaid, the children's maid, the caretaker, etc. the two grooms are good people. The cook quite easy going, the lady's maid 30 years old, the chambermaid very pretty, often my companion, the children's maid a good elderly lady, the caretaker my love-rival. The two grooms are better suited to the horses than to humans. The Count, quite coarse, the Countess proud but sensitive, the little Countesses good children.

Der Rentmeister paßt ganz zu seinem Amte, ein Mann mit außerordentlichen Einsichten in seine Taschen u. Säcke. Der Doktor, wirklich geschickt, kränkelt mit 24 Jahren wie eine alte Dame. Sehr viel Unnatürliches. Der Chirurgus, mir der liebste, ein achtbarer Greis von 75 Jahren, stets heiter u. froh. Gott gebe jedem ein so glückliches Alter. Der Hofrichter, ein sehr natürlicher, braver Mann. Ein Gesellschafter des Grafen, ein alter lustiger Geselle, u. braver Musikus, dient mir oft zur Gesellschaft.

Der Koch, die Kammerjungfer, das Stubenmädchen, die Kindsfrau, der Beschließer etc. 2 Stallmeister, sind gute Leute. Der Koch ziemlich locker, die Kammerjungfer 30 Jahr alt, das Stubenmädchen sehr hübsch, oft meine Gesellschafterin, die Kindsfrau eine gute Alte, der Beschließer mein Nebenbuhler. Die 2 Stallmeister taugen viel besser zu den Pferden als zu den Menschen. Der Graf, ziemlich roh, die Gräfinn stolz, doch zarter fühlend, die Contessen gute Kinder.

[Dok 67]

Firstly Schubert disposes of the bursar, responsible for the finances of the household, as intellectually limited, concerned only with money. Whether Schubert had already had a run in with the man responsible for paying him his servant's pittance out of his well-filled pockets and purses we are not told. There is clearly no love lost between the young musical genius and this dry old stick.

Schubert cannot resist the oxymoron of the young doctor, 'really skilful', who is 'ailing like an old lady'. In the description of the surgeon and the magistrate, though, we find genuine affection. They seem to have the natural, easy-going, genuine personalities that Schubert always preferred. Throughout his adult life he always avoided 'the stiff people', inflated with pomposity and self-esteem.

The magistrate is a 'companion of the Count' and as such, he is the only one who crosses the otherwise impenetrable feudal line between the noble family upstairs and the servants below stairs.

After he has dealt with the below-stairs notables, Schubert provides us with a quick review of the remainder of the servants. Once again, after a blanket judgement 'good people', some of the 'good people' are dealt with quite contemptuously: 'The two grooms are better suited to the horses than to humans'.

Here writes Schubert the outsider. He was a servant in the Count's household – he sleeps in servant quarters, eats with them and spends his time in their quarters when he is not entertaining his aristocratic hosts. That is his feudal status. His level of genius counts for nothing in this situation.

Mozart exploded into vulgar rage and streams of obscenities against the aristocratic dolts who demanded not just obedience, but obsequious obedience from him. Schubert, better disciplined by his Jesuit father, just sucks it all up: what else can he do? Even the servants have no particular respect for him: he is the new boy in the group and will be low down in the pecking order.

He seems to receive no special recognition from his employers. There is certainly no empathy between the little musician and the Count ('coarse') and his Countess ('proud'). Those four months must have been quite long ones for the 21-year-old who in Vienna enjoyed his pipe in the company of friends in the tavern or took part in the wild doings of the Nonsense Society.

Schubert's use of the word 'coarse' to describe Count Esterházy is at odds with Otto Deutsch's description of him: he was 'an educated, widely-read man, a "son of Nature who grew up among barbarians", according to his own description'. [Dok 62] Perhaps the different viewpoints can be explained in the difference between knowing someone and working as their servant or even just living as their guest. Dante's words spring to mind. Of his long years of exile, dependent upon friends and strangers, he wrote:

You shall know how salt is the taste of another man's bread and how hard is the way up and down another man's stairs.

Tu proverai sì come sa di sale

lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle

lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale.

Dante. Divina Commedia, Paradiso Canto XVII, lines 58–60.

But facts overtake us: however coarse the Count and however proud the Countess, Schubert would return to them in Zseliz in 1824, when he would be treated with a little more respect for his genius. A little more.

The holiday romance

Schubert's remarks about 'the chambermaid very pretty, often my companion', then amplified shortly afterwards with 'the caretaker my love-rival' hint at romance.

Quite some attention has been devoted to that romance in the millennial Schubert scholarship. Apart from simple curiosity, this attention was largely a reaction to the mainly American obsession of the 1990s with Schubert's supposed homosexuality, which was based on many misreadings, mistranslations, misunderstandings and driven by a huge portion of wishful-thinking. The cultural agenda of the times was and still is clear: the more great figures who turn out to be homosexuals repressed by harsh social norms, the better.

Those who are not familiar with the patterns of discourse in 18th and early 19th century German may have been discomfited by all the emotion thrown about in these letters between adult men: the love, the kisses, the think-about-me and the declarations of undying friendship. Those who are familiar with the canon will find the feelings in these letters completely normal for the age.

The easy expression of such deep feelings strikes the modern person as odd – camp, even – and gives the translator much work to do in order to avoid misleading the modern reader with the natural effusiveness of that time.

As far as Schubert's love interest is concerned, her name was Pepi Pöcklhofer. Thanks to the archival research of Rita Steblin in 2008 we now know much more about Pepi. [Pepi passim]

Before Steblin's research, it was generally assumed that Pepi was some kind of flighty – go on, let's say it: perhaps even 'easy' – denizen of the below-stairs culture. Some commentators have even gone the extra mile and named her as the source of Schubert's syphilis. Since he met Pepi at Zseliz in 1818 and his syphilis showed its first symptoms in 1821/22 the four-year incubation period is simply a medical impossibility. One more insult to the working girl.

Thanks to Steblin, we now know her as Josepha 'Pepi' Pöcklhofer. She was born on 23 March 1797 (two months after Schubert) and died on 11 August 1879. Leaving out the unfortunate dead infant siblings, she was the fourth child of five. She was born to the 'castle administrator' Joannes Pöcklhoffer and his wife Johanna, née Magschitz. Her father had a responsible and trusted position and made a steady career until his death on 12 December 1821 at the age of 59. We don't know exactly when her mother died, but she was still alive in 1842. Pepi grew up in the refined environment of various castles and country houses and would have had a solid education.

Pepi didn't marry Franz Schubert, of course, but nor did she marry his rival, the caretaker Johann Röhr. She took her time, in fact: she married Joseph Rößler (1788-1852) on 18 July 1830. She was thirty-three years old by then. We think that Rößler entered service with the Esterházys in 1826. He was a widower with one son, whom Pepi, who herself seems to have had no children, looked after as her own. The marriage records show that Count Esterházy was one of their witnesses – a rare honour which demonstrates the standing in which the pair must have been held by their employer. We don't know exactly what Rößler's post with the Esterházys was at the time of the marriage, but at his death 22 years later he was still in their service and was a Haushofmeister, the administrator or steward of the household who was responsible for the other personnel.

We do not really know, but everything here suggests the union of Joseph and Josepha was that of two serious and industrious people. Joseph died on 24 December 1852 in Vienna. Pepi would outlive him by another 27 years.

At her death on 11 August 1879 in Vienna, 83 years old, Pepi left an estate valued at nearly 6,350 florins – a considerable sum that is testament to a prudent bourgeois family life.

As an aside, it is interesting to note the similar – though not identical – curve that the life of the other woman romantically associated with Schubert took: Therese Grob (1798-1875). Apart from birth and death dates that were so close, Therese also married a solid bourgeois man, the master baker Johann Bergmann. They were married on 21 November 1820. Johann died on 17 November 1840. On Theresa's death on 17 March 1875 she, too, left substantial assets. Another prudent bourgeois family life.

It is clear from Schubert's immediate affinity for Pepi the chambermaid (and, of course, the lady's maid, Therese Tschekal, the other of the two women whose conversation eased his loneliness, the 'couple of good girls') that she was at an intellectual and emotional level to which he could relate.

Pepi had a Viennese background and thus they shared a dialect and a world-view. They were almost the same age and she had enjoyed an upbringing that was anything but coarse. We can imagine that she was a sensitive and empathetic partner for the lonely young composer. Our depiction of her as a serious person, derived from the basic facts of her biography, makes it even more likely if we are right that the serious Franz found her to be something of a soulmate.

Yes, of course, all this is speculation, but slightly less wild and offensive speculation than a lot of the nonsense that has been written about her. It is also true to say that, for a soulmate, she figures only marginally in Franz's letters. But from the deeply introverted Franz Schubert we would expect nothing else. In fact, she is the only woman he ever mentioned in any romantic context. All the other 'passions' of Schubert's life we hear about only in hints and allusions from his friends, most of them made many years after his death. As such, applying the term 'soulmate' to Pepi Pöcklhofer is completely justified.

Why nothing seems to have come of the friendship and why she seems to have rejected him when they met again on Schubert's second visit to Zseliz in 1824 goes beyond our present scope.

The closing irony

Up to now I have been spared roast meat. Now I have nothing more to say; that I, with my innate honesty, get on well with all these people I scarcely need to say to you, who know me so well.

Vom Braten bin ich bisher verschont geblieben. Nun weiß ich nichts mehr; dß ich mit meiner natürlichen Aufrichtigkeit recht gut bey allen diesen Leuten durchkomme, brauche ich euch, die ihr mich kennt, kaum zu sagen.

[Dok 67]

His friends would have found Schubert's jocular remark about the meanness of the food the servants received amusing but sad: the 'up to now' actually adds up to a six week roast meat deficit.

His friends would know: Schubert liked his grub and regulated his intake in accordance with the Viennese tradition of not wasting space on a plate with anything other than meat. The reports of travellers who strayed into Vienna, supplemented by the remarks of Viennese doctors, all express wonderment at the quantities of meat that went into an Austrian meal. No edible animal was safe in Austria.

In this connection, Schubert fans will remember the plaintive note the fifteeen year-old wrote from the Stadtkonvikt– where he was also fed without generosity – to his brother Ferdinand (we think) asking for a few pence so that he could buy something to fill up the gaps in his stomach – his father's pitiful allowance being completely inadequate for that purpose. [Dok 22f Schubert an seinen Bruder Ferdinand(?) Den 24. November 1812.]

So far in Zseliz he has had to survive all of six weeks without a roast.

Schubert's roast meat deficit leads us to yet another irony in his irony-laden stay in Zseliz: the cook at the time of Schubert's visit, Georg Buchmayer, had a high reputation and received a salary to match – 1,000 florins a year. He was the highest paid servant in the household, according to Otto Deutsch. If we believe Schubert, who may be mocking his own love of food for his friends, the products of Buchmayer's skill did not appear to trickle down to the starving composer below stairs.

They would also have been amused by his reference to his own natürliche Aufrichtigkeit, 'innate honesty'. Schubert was not one for flattery or blandishments – he was indeed innately honest, which meant that he held nothing back in giving his opinions. He was thus an expert in the art of the Wiener Schmäh. He had been in Zseliz six weeks by this time and the other 'good people' below stairs would certainly have experienced the verbal rapier of the native Viennese. The chances of his 'getting on well with all these people' are probably zero. The fine irony of his last statement, so clear to those 'who know me so well', could apply to most of the letter.

And now, dear friends, live very well, write to me soon. It is my dearest, happiest distraction to read your letters ten times over. Give greetings to my dear parents and tell them how much I want a letter from them.

With eternal love,

Your faithful friend

Und nun lieben Freunde, lebt alle recht wohl, schreibt mir ja recht bald. Es ist meine theuerste, liebste Unterhaltung eure Briefe zehnmal zu lesen. Grüßt meine lieben Altern, u. meldet meine Sehnsucht nach einen Brief von Ihnen.

Mit ewiger Liebe

Euer treuer Freund

[Dok 67]

Nothing very remarkable, except for another plea for people to write to him.

Ignaz: seething and straining under the yoke

So far we have learned quite a bit about the personality of Schubert, about the common culture he shares with his friends and about Schubert's low standing in feudal society.

In the following correspondence with his brothers Ignaz and Ferdinand we shall learn a lot about the dynamics of his family and about their shared beliefs.

In rural and feudal Zseliz, Schubert was an outsider whose own roots were deep in the young metropolitan culture of Vienna. He began to miss that urban life almost as soon as he arrived on the estate.

Under Franz II/I 's 'belljar', his security and censorship regime, it was wise not to express your true feelings about the state and particularly the clergy. Opinions had to be expressed circumspectly, using techniques of writing that was intended to be read 'between the lines'. These techniques are still observable in texts written under oppressive regimes. There was a use of ambiguity and implication that appears masterful to us today but which was second nature then.

Between the Schubert brothers these feelings could be expressed openly though. The letters thus give us an insight into some of their opinions that we would not normally hear about.

[Vienna] 12 October [1818]: Ignaz Schubert to his brother Franz

Dear Brother!

… Finally, finally at last, you will think to yourself, we get to see a few lines. Yes, yes, I believe that you would not have got anything to see, were it not for the fact that to my relief the wonderful school holidays have arrived, in which I, free of morose thoughts, have enough leisure, peace and quiet to write you a proper letter.

Lieber Bruder!

… Endlich, endlich einmal, wirst Du Dir denken, bekommt man doch ein paar Zeilen zu sehen. Ja, ja, ich glaube, Du würdest noch nichts zu sehen bekommen haben, wenn nicht endlich einmal zu meinem Trost die lieben Vakanzen angerückt wären, wo ich Muße genug habe, in ungestörter Ruhe und ohne verdrießliche Gedanken, einen ordentlichen Brief zu schreiben.

[Dok 70]

At the time of writing this letter Ignaz was 33, Ferdinand 23 and Franz 21 (the long gap between Ignaz and Ferdinand being the ten years of dead babies). The morose thoughts appear straight away, though:

You happy person! how enviable is your lot! You live in a sweet, golden freedom, can give free rein to your musical genius, can cast your thoughts in whatever direction you choose, are loved, admired and idolised, whilst I as a miserable schoolmasterly beast of burden am exposed to all the coarseness of wild youth, exposed to a host of abuses and on top of it all abjectly subjugated to a thankless public and stupid religious fatheads.

Du glücklicher Mensch! wie sehr ist Dein Los zu beneiden! Du lebst in einer süßen, goldenen Freiheit, kannst Deinem musikalischen Genie vollen Zügel schießen lassen, kannst Deine Gedanken wie Du willst hinwerfen, wirst geliebt, bewundert und vergöttert, indessen unsereiner als ein elendes Schullasttier allen Roheiten einer wilden Jugend preisgegeben, einer Schar von Mißbräuchen ausgesetzt ist, und noch überdies einem undankbaren Publikum und dummköpfigen Bonzen in aller Untertänigkeit unterworfen sein muß.

[Dok 71]

At the time of writing, Ignaz had applied unsuccessfully for at least four positions elsewhere. His brother Ferdinand had escaped from the Himmelpfortgrund school to be an assistant teacher in the orphanage school in 1811, finally getting a full teaching position in 1820, two years after this exchange. Ignaz the free thinker, the slave of the pious, Jesuit-trained father, had clearly got himself into trouble recently:

You will be surprised when I tell you that things have got to the stage in our house, that one does not trust oneself to laugh, when I tell a superstitious funny story from the religious education lesson.

Du wirst Dich wundern, wenn ich Dir sage, daß es in unserm Hause schon so weit gekommen ist, daß man sich nicht einmal mehr zu lachen getraut, wenn ich vom Religionsunterricht eine abergläubisch lächerliche Schnurre erzähle.

[Dok 71]

The fact that Ignaz needs to tell his brother about the development of a new religious severity in the Schubert family needs some explanation.

The bigots of Rossau

We firstly have to remember that composer Franz had moved out of the family house to Schober's apartment in the late autumn of 1816 and stayed there until the summer of 1817. According to Schober's account much after the fact, this had been Schober's masterstroke to free little Franz from this drudgery. It didn't work for long, though.

Franz returned to teaching at the Himmelpfortgrund school from August to December 1817 and continued there to July 1818. In other words, just before his time in Zseliz, he was teaching in his father's brand new school in Rossau. Schober's bid to free Schubert had ultimately come to nothing.

We can reasonably assume that Franz kept out of his father's way as much as he could: his spare time was spent on his music. But, in the background, the mood had changed: 'things have got to the stage in our house', writes Ignaz. The difference between now and the good old days in the Himmelpfortgrund school is that the religious context had changed. In Rossau the bigots are now in charge.

Ignaz's words and anger should not be misunderstood as applying directly to his father. Franz Theodor is also the servant of the clerical authorities in charge of his school. Let us remember that he was the father of Franz Ignaz Vietz, the baby born out of wedlock who never made the family chronicle (he would have been 35 years old in 1818), that he got his bride Elisabeth to the church in the nick of time before the present Ignaz came into the world. He was not himself without sin although he was, in his own words, 'happy to moralise'. He was only too aware of the danger of loose words about religion and more particularly about the clerical heirarchy.

Franz Theodor's exemplary reputation as a religious and educational conformist had led to his being offered the post of school director in Rossau in order to bring the school up to scratch after a long decline under his disgraced predecessor. The previous director of the school, Valentin Rosen, who had taught there for 15 years, had been removed from his post in Rossau, to be replaced by Franz Theodor in January 1818.

Over the years more than 20 accusations of inappropriate behaviour with girls, single and married women and widows had been made against Rosen. He also seems to have had a habit of going into the pub and loudly venting his views about the stupidity of the clerical establishment. He is supposed to have said that his hatred for priests was so great that on his deathbed whilst the priest was performing the last rites he would stick his finger up the cleric's backside. He had supposedly been heard to call the priests in the abbey 'stinking clerics' and he had conspicuously eaten meat on fast days.

In the circumstances it is only to be expected that Father Candidus Lösch, the priest in Rossau, would want to get rid of him. Lösch himself seems to have been solidly prüdish, which certainly would not endear Rosen to him or him to Rosen. For example, only a month before Ignaz wrote this letter, Lösch had joined with Franz Theodor to block the opening of an amateur playhouse – that cauldron of sin – that was going to be established in the tavern Zum grünen Tor next to the school.

Amusingly for modern sensitivities, Valentin Rosen, a danger to all females of any age it would appear, was not completely dismissed (there was still a teacher shortage, after all) but took over Franz Theodor's post in Himmelpfortgrund.

Franz Theodor Schubert's promotion to the Rossau school and Valentin Rosen's demotion to the Himmelpfortgrund school shows what a substantial step up it was for Schubert's father to be put in charge of the renovated school. That had been a substantial promotion.

After the Rosen affair, Franz Theodor would know quite clearly what trouble loose words could cause. He had been recommended for the prestigious and lucrative Rossau position on the strength of glowing reports about his character and educational success. Ignaz being free with his opinions in this situation was the last thing he wanted.

Ignaz's words also imply that there may have been a time when in the educated and not unenlightened Schubert family a joke at the expense of the religious heirarchy would have caused general amusement. No longer, apparently.

The clerical fatheads

You can also easily imagine that under such circumstances I am often seized with internal anger and that I only know freedom from its name. See, from all these things you are now free, you have been delivered, you see and hear nothing more of this awful state of affairs and in particular nothing more from our clerics, about whom one should remind you of, certainly not for the first time, the comforting lines of Herr Bürger:

Don't envy the army of clerics

For their fat heads,

Most of them are hollow

and empty like the onion domes of their church towers.

Du kannst Dir also leicht denken, daß ich unter solchen Umständen gar oft von innerlichem Ärger ergriffen werde, und die Freiheit nur dem Namen nach kenne. Siehst Du, von allen diesen Dingen bist Du nun frei, bist erlöset, Du siehst und hörst von all diesen Unwesen und besonders von unseren Bonzen nichts mehr, von welchen letzteren man Dir gewiß nicht erst den trostreichen Vers des Hrn. Bürger zurufen muß:

Beneide nicht das Bonzenheer [recte: Doch neid’ ich nicht]

Um seine dicken Köpfe,

Die meisten sind ja hohl

und leer Wie ihre Kirchturmknöpfe.

[Dok 71]

The heavy-handed censorship imposed on the Austrian Empire during the long reign of Franz II/I was not just political but also religious. Criticism of Catholic doctrine, but particularly criticism of the hierarchy was a serious offence. Lapses in morality or decorum were also persecuted with vigour with both legal and/or social condemnation. In the era when Germany was awash with Protestantism, the Austrian empire saw itself as the great bulwark of Roman Catholicism in German-speaking Europe.

As we have already noted, father Schubert, the proud possessor of his shiny new school in Rossau, must have been terrified that a wrong word from one of his sons could imperil all that he had achieved.

The fact that Ignaz is quoting Gottfried August Bürger (1747-1794) is a strong indicator of his opinions. Bürger is remembered nowadays almost solely for his Adventures of Baron von Münchhausen, but he wrote many bitterly anti-establishment poems, even more vicious than the work of Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart.

Family life

After grumbling about religious oppression, Ignaz now gives us a good insight into the close knit community in which the Schuberts grew up. This was clearly no rarifed hothouse for young geniuses, a fact which is always reflected in Franz Peter's grounded approach to life. It also further refutes the picture of Franz Theodor as a grim, religious bigot. Things used to be better, and there was still the community around them. The bigotry only came recently:

… Now to something different. The name day of our Papa was marked with a celebration. The entire staff of the Rossau school with wives, brother Ferdinand and wife, our aunt and Lenchen and the entire clan from Gumpendorf were invited to an evening party, at which we valiantly ate and drank and which was very merry.

… Nun zu etwas anderem. Das Namensfest unseres Herrn Papa wurde feierlich begangen. Das ganze Rossauer Schulpersonal samt Frauen, der Bruder Ferdinand samt Frau, nebst unserm Mühmchen und Lenchen und der ganzen Gumpendorfer Sippschaft wurden zu einem Abendzirkel eingeladen, wo wacker geschmauset und getrunken wurde und es überhaupt sehr lustig herging.

[Dok 71]

The name day for Franz Peter's father was that of Saint Francis of Assisi (1181?-1226, known as Franz Seraphicus) and fell on 4 October. The party therefore took place on 3 October 1818.

Before the eating and drinking we played quartets, at which we heartily regretted that our Meister Franz was not in our midst; we gave up quite soon.