Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen

Richard Law, UTC 2017-04-30 10:01

One more contribution to our wistful theme: if only Franz Schubert had had better lyricists. Or, put another way round, if only Schubert had not dignified so much bad verse with his music.

The dilettantes from his 'circle of friends' scribbled down their adolescent ramblings, epigones of the works of a bygone ages and styles, the turgid, safe texts that their monkish teachers had allowed them to read, passed the resulting scraps of paper across the table to Schubert, who would do something with them. Schubert – as we might expect in such a sensitive song composer – was demonstrably a very skilled reader of verse. But beggars can't be choosers – and he was a beggar at the time – and so he did what he could with this tosh.

None of the several anthologies of German poetry on my shelves contains any poem by Mayrhofer: as poetry his work simply does not make the cut. Ditto Schober, whose efforts are drivel. Schubert did his best with An die Musik and the musical result appealed to many, but the poem itself is fustian and shallow – it could have been written a century before, there is nothing in it that is worth discussion. Like so much other tosh, elevated by Schubert's music it has survived. Grillparzer was right: dilettantes, the lot of 'em.

Stolberg on the water

Enough grumbling! As we have done before [Grillparzer,Schubart,Goethe and Goethe], let's see what our musical genius can do when he stands on the shoulders of a lyrical genius, in the present case Graf Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg (1750-1819) and his poem Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen, für meine Agnes, first published 1783. Schubert set it to music in 1823 and it is now catalogued as Auf dem Wasser zu singen, D 774, Opus 72.

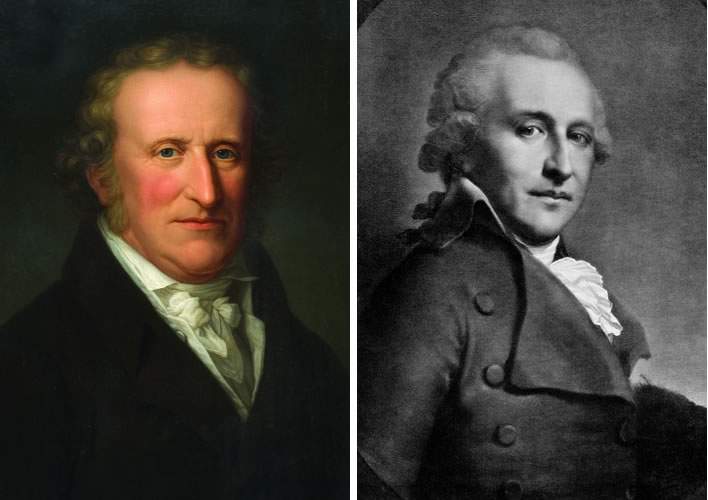

Graf Friedrich Leopold zu Stolberg-Stolberg

Left: Portrait by Friedrich Carl Gröger, 1818? Right: Stolberg? Unknown source, ND.

Here is Stolberg's poem, accompanied by the usual dull-as-dishwater literal translation that so delights our reader(s).

Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen, für meine Agnes

Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen

Gleitet wie Schwäne der wankende Kahn;

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendroth rund um den Kahn.

Through the shimmer of the reflecting waves

The rocking boat glides like swans;

Oh, on the joy of softly shimmering waves

The soul glides like the boat;

Because down from Heaven on to the waves

the red of the evening dances around the boat.

Ueber den Wipfeln des westlichen Haines

Winket uns freundlich der rötliche Schein;

Unter den Zweigen des östlichen Haines

Säuselt der Kalmus im rötlichen Schein;

Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines

Atmet die Seel' im erröthenden Schein.

Above the treetops of the western grove

The red glow waves in friendship to us;

Under the branches of the eastern grove

The reeds rustle in the red glow;

The joy of Heaven and the peace of the grove

Drinks in the soul in the reddening glow.

Ach es entschwindet mit thauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit.

Morgen entschwinde mit schimmerndem Flügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Bis ich auf höherem stralenden Flügel

Selber entschwinde der wechselnden Zeit.

Oh away with dewy wings

time flies from me on the cradling waves.

Tomorrow on shimmering wings

May time flee as yesterday and today,

Until I on higher radiant wings

Myself escape changeful time.

The text is that of the Hamburger Musenalmanach fur das Jahr 1783, ed. Voß und Goeckingk, Hamburg, 1782, p. 168f [first appearance]. Translation ©FoS.

Parola-rima

Well, before we have even finished the first verse we literary types are thinking: what is going on here? Look at the ends of the lines – those are not rhymes but 'merely' repeated words. Each six-line verse manages to end its lines with one of a single word pair: Wellen-Kahn, Haines-Schein, Flügel-Zeit. Germanists will search long and far for its like and find only one other poem – also by Stolberg and written about the same time.

[Promies 309] has pointed out the frequency of this technique in Romance literature, particularly Provençal and early Italian poetry, where such rhymes are called parola-rima, 'word-rhymes'. There is no evidence that Stolberg was familiar with these sources, making it likely that the use of word-rhymes in this poem is something he dreamed up himself. We shall see why he did this later.

Despite that, a look at the use of the technique makes an interesting excursion. Let's keep the excursion brief though: if you want more detail you have to go to the original sources.

The Provençale troubadour Arnaut Daniel is credited with the first use of parola-rime in a verse form called the sestina. The troubadours and their Italian admirers such as Dante and Petrarch were fond of showing off their skill by writing in fixed forms they called trobars-clus, 'locked-songs'. The sestina is one of these forms – and it is a formidable one. Even the versifiers of the fin-de-siècle 'Rhymers' Club' kept away from it.

It is a verse form that has six stanzas each containing six lines, sometimes concluded with an envoi of three more lines.

Strictly speaking the sestina is not rhymed, certainly not as we would understand it, but the lines end in parola-rima. The repetition scheme – pay attention now – is v1[ABCDEF] v2[FAEBDC] v3[CFDABE] v4[ECBFAD] v5[DEACFB] v6[BDFECA] envoi[ECA]. Those who really wanted to show off could put in the odd internal rhyme, too. We on this blog never leave anyone wanting more, so here is are the first two stanzas of Arnaut's Lo ferm voler qu'el cor m'intra, the first known sestina of its kind. It is untranslated here, because we only care about the use of word-rhymes:

Lo ferm voler q'el cor m'intra

no.m pot becs jes escoissendre, ni ongla

de lausengier, qui pert per mal dir s’arma;

e car no l'aus batr'am ram ni ab verga,

sivals a frau, lai on non aurai oncle,

jauzirai joi en vergier o dinz cambra.

Qan mi soven de la cambra

on a mon dan sai que nuills hom non intra

anz me son tuich plus que fraire ni oncle-

non ai membre no.m fremisca, ni ongla,

aissi cum fai l'enfas denant la verga:

tal paor ai qe.il sia trop de l'arma.

The text is that of Arnaut Daniel, Lo ferm voler qu'el cor m'intra, Testo critico, Lirica Medievale Romanza ©Sapienza Università di Roma.

If you want to see a crash and burn attempt to translate one of Arnault's sestinas whilst preserving the word-rhymes you should go to: Pound, Ezra. 'Arnaut Daniel' in Literary Essays of Ezra Pound. London: Faber and Faber, 1960. p. 135-139.

Enough of excursions into irrelevant regions: back to Stolberg and his Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen. He was a skilled poet – there are plenty of conventional rhymes he could have come up with, but he chose to use 'word-rhymes', despite the obvious risk of monotony. Why? We need to look at the structure a little further before we can answer that.

Standing back from the poem a little, we notice its strict architecture, quite worthy of a troubadour's trobar-clus in its symmetry: three stanzas, each containing three line-pairs. This structure is not merely typography but also punctuation: in the first two stanzas the line-pairs are punctuated [line line];[line line];[line line]. In the last stanza [line line].[line line],[line line].

The lines in each pair are tightly enjambed – that is, the syntax of the text flows over the typographic line endings and there can therefore be no punctuation between them.

We now see how the shared identity of the line-pairs is reinforced by the word-pairs they have in common. The three line-pairs of each stanza are variations on a stanza-theme, if you like, or aspects of a shared reality. The lines in the pairs are similar, but not identical. The Scholastic philosophers would have had fun with Stolberg's poem, that is sure. [Promies 310] called each line-pair a Sinneinheit, a 'sense-unit', giving us a 3x3 architecture for the poem.

Internal structure

Each of the line-pairs is linked to its immediate neighbour(s) not just by the shared word-pairs but by numerous internal rhymes, repetitions and semantic alliances. Here is the poem repeated with the line-pairs and only the other major effects highlighted.

Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen

Gleitet wie Schwäne der wankendeKahn;

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmerndenWellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendroth rund um den Kahn.

Ueber den Wipfeln des westlichenHaines

Winket uns freundlich der rötlicheSchein;

Unter den Zweigen des östlichenHaines

Säuselt der Kalmus im rötlichenSchein;

Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines

Atmet die Seel' im erröthendenSchein.

Ach es entschwindet mit thauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit.

Morgen entschwinde mit schimmerndemFlügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Bis ich auf höherem stralendenFlügel

Selber entschwinde der wechselnden Zeit.

If we were also to mark the impressive number of assonances, consonances and alliterations the whole poem would be almost entirely coloured. As it is, just a glance reveals the astonishing density of the composition and the large number of repetitions and internal references.

When we stand back a little and look at the way the line-pairs are linked we notice that this is done through shared similarities with their neighbours. The differences that there are often just transformations within a shared semantic field: rot-rötlich-errötend. But we can also see the line-pairs as layers or reflections, with their content transformed by the movement of the spiegelnden Wellen, the reflecting waves.

You can look at them as metaphoric transformations from the real world to the irreal idea, you can also look at them as transparent yet iridescent overlays. Was this Stolberg's intention? I have no idea – but he was a clever, extremely well-educated chap and I would certainly not put such a construction past him.

Readers now slumped before their screens in despair might lift up their eyes to note that whereas in the first stanza the direction of motion was downwards, herab, in the third stanza we are looking upwards from the earth to Heaven.

Finally in this section: we might have expected it of some much later practitioners of the poetic trade such as Schwitters or Morgenstern, but in 1782 Stolberg gives us a phonetic symphony of the definite article in German, aided and abetted by one or two near homophones:

Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen

Gleitet wie Schwäne der wankende Kahn;

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wieder Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendroth rund um den Kahn.

Ueber den Wipfeln des westlichen Haines

Winket uns freundlich der rötliche Schein;

Unter den Zweigen des östlichen Haines

Säuselt der Kalmus im rötlichen Schein;

Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines

Atmet die Seel' im erröthenden Schein.

Ach es entschwindet mit thauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit.

Morgen entschwinde mit schimmerndem Flügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Bis ich auf höherem stralenden Flügel

Selber entschwinde der wechselnden Zeit.

What the pedant scribbles, the musically sensitive reader hears and feels.

Metrical structure

But the most powerful mark of poetic genius in the poem is its metrical structure – its rhythm, in other words. Schubert, the musical genius, must have recognised the poem's metrical qualities at first glance. Here is the first verse on the metrical autopsy table:

Mitten im | Schimmer der | spiegelnden | Wellen

Gleitet wie | Schwäne der | wankende | Kahn;

Ach, auf der | Freude sanft|schimmernden | Wellen

Gleitet die | Seele da|hin wie der | Kahn;

Denn von dem | Himmel her|ab auf die | Wellen

Tanzet das | Abendrot | rund um den | Kahn.

Those who care about such things, scalpels twitching, will note that Stolberg chose the 'dactylic foot', dum-da-da, as his basic measure. Blue marks the 'long' or 'stressed' vowels, green the 'short' or 'unstressed' vowels.

There are four 'feet' on each line, meaning that we are dealing with a form known as the 'dactylic tetrameter'. The prosodists, when they have recovered from their swoon at our casual use of 'long' and 'stressed', will have their hands waving in the air so they can point out that all the line endings are 'catalectic', that is that they are incomplete dactyls. We have indicated this in our mark up by ending the lines with the missing unstressed syllables, for example n | Kahn. , which has two unstresses missing. Whether this feature, strictly speaking, is catalectic is a discussion we might take out into the carpark.

[Promies 311] points out how closely the dactylic tetrameter from the pen of Stolberg replicates the wave movements that are such an integral part of the meaning of the poem. The dactylic foot was always known as a measure of rolling movement, but Stolberg leverages the form further through the use of a number of adjectival present participles that are in themselves complete dactylic feet: spiegelnden, wankende, schimmernden, wiegenden, stralenden, wechselnden.

Promies concludes:

I know of no poem in the German language in which the rhythms of wave movement, their evenness despite the gentle variablity of the metre are so exactly transformed into spoken movement…

Promies 311.

It is tasteless to hack around in this poem with our metrical scalpel: Schubert grasped immediately what Stolberg was at, just as in their turn Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Gerald Moore grasped what both the poet and the composer were at.

Imagery

Well, we have declared Stolberg's Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen to be a masterpiece without even looking at its content yet. Here goes.

The general location of the action of the poem is determined in the first two lines: there is a boat gliding over water, it is a Kahn, a generic small boat that might be translated as 'dinghy' or 'skiff', except that these words would be too specific – if 'boat' is good enough for the Beatles, Picture yourself in a boat on a river / With tangerine trees and marmalade skies, it's good enough for your translator.

The water is in gentle motion, just enough to rock the small boat. The time is evening, specifically sunset, das Abendroth.

Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen

Gleitet wie Schwäne der wankende Kahn;

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendroth rund um den Kahn.

Through the shimmer of the reflecting waves

The rocking boat glides like swans;

Oh, on the joy of softly shimmering waves

The soul glides like the boat;

Because down from Heaven on to the waves

the red of the evening dances around the boat.

The general location becomes more specific in the second stanza, which is rich in location detail: we now see that the water is a small lake in a forest grove or clearing – it has to be small because we can clearly see both shores. The sunset has reached the tips of the trees in the west. The light of the sunset coming from the west illuminates the reeds on the eastern side of the lake.

To be precise – which we have to be in this poem – the reeds are not just under the branches but are under the 'twigs' of the trees, that is, the small branches hanging down under the trees. Translating this as 'twigs' would, however, be more misleading than 'branches'. The clearing is peaceful. As the sun is setting the glow becomes redder, errötend.

Ueber den Wipfeln des westlichen Haines

Winket uns freundlich der rötliche Schein;

Unter den Zweigen des östlichen Haines

Säuselt der Kalmus im rötlichen Schein;

Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines

Atmet die Seel' im erröthenden Schein.

Above the treetops of the western grove

The red glow waves in friendship to us;

Under the branches of the eastern grove

The reeds rustle in the red glow;

The joy of Heaven and the peace of the grove

Drinks in the soul in the reddening glow.

There is no 'I' in this scene so far – in fact, no people at all were mentioned directly in the first stanza. Our only hint – and a hint was all it was – was that there are two people in the boat: der Kahn, 'the boat', singular, is gliding like Schwäne, 'swans', plural, over the water. That hint may seem far-fetched, but now, in the second line of the second stanza, the red glow 'waves to us' – that is, two or more people, inconceivably the 'royal we'.

[…]

Gleitet wie Schwäne der wankende Kahn;

The rocking boat glides like swans;

[…]

Winket uns freundlich der rötliche Schein;

The red glow waves in friendship to us;

In the first stanza, between the first and second line-pairs, a transformation takes place: the boat/swans undergo a further metamorphosis into the soul. The third line-pair then adds a religious aura to the scene: the evening light von dem Himmel herab shines down from Heaven (not simply 'the sky') and dances on the waves around the Kahn/Schwäne/Seele.

Let us not try the reader's patience with an essay on the philosophical understanding of reflection as a transformation of reality, particularly in the works of Plato, a philosopher well known to Stolberg. We made a start here, the rest is up to the reader.

Mitten im Schimmer der spiegelnden Wellen

Gleitet wie Schwäne der wankende Kahn;

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendroth rund um den Kahn.

Through the shimmer of the reflecting waves

The rocking boat glides like swans;

Oh, on the joy of softly shimmering waves

The soul glides like the boat;

Because down from Heaven on to the waves

the red of the evening dances around the boat.

The third line-pair of the second stanza ties these elements together: the joy of heaven and the peace of the grove are breathed in by the soul. Stolberg, the translator of Homer, Plato and Aeschylos, would not use 'breath' and 'soul' in such proximity without thinking of their shared identity in the Greek mind: Psyche [the soul/mind, ψυχή], Pneuma [the breath/spirit/soul, πνεῦμα]. Agnes, for whom the poem is written, whom we shall meet shortly, took as her pen name 'Psyche'. Is this titbit significant? Probably not.

Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines

Atmet die Seel' im erröthenden Schein.

The joy of Heaven and the peace of the grove

Drinks in the soul in the reddening glow.

The third stanza introduces the theme of time: the boat drifts and rocks on its 'cradling' waves, but time disappears on its 'dewy wings'. It will do so tomorrow, just as it did yesterday and as it is doing today. Wieder alerts us to the cyclical – wavelike – nature of the passing of days, the fundamental counter of time passing.

In this stanza, for the first time in the poem, an ich, 'I', and a mir, 'me', appear. The final line-pair makes the transition from the changeability of the span of human life into the timelessness of the afterlife/eternity.

Ach es entschwindet mit thauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit.

Morgen entschwinde mit schimmerndem Flügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Bis ich auf höherem stralenden Flügel

Selber entschwinde der wechselnden Zeit.

Oh away with dewy wings

time flies from me on the cradling waves.

Tomorrow on shimmering wings

May time flee as yesterday and today,

Until I on higher radiant wings

Myself escape changeful time.

Ach

A key word in the poem is Ach, an exclamation usually translated as 'Oh'. Such a small word, so often a verbal filler in other poetry, appears in the present poem twice and plays an important role.

In the first instance, at the beginning of the third line, it is used with a comma as a caesura, a metric break – just the kind of brief pause you might experience at a wave peak and as such a stroke of metrical genius.

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Oh, on the joy of softly shimmering waves

The soul glides like the boat;

It is an abbreviated way of expressing surprise at the sudden realisation of the parallel between the boat gliding on the water and the soul gliding on the joy brought forth by the glinting waves. The word Ach guides the transition from the 'real' scene into the metaphor of the soul, the 'irreal' scene. The word might be translated into English by a phrase such as 'just think' or 'just like'.

The second Ach at the beginning of the third stanza is not used as a caesura but has a similar semantic function to the first occurrence.

Ach es entschwindet mit thauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit.

Oh away with dewy wings

time flies from me on the cradling waves.

Ach marks the sudden insight into the 'irreal' metaphor behind the 'real-world' situation of the sunset at the woodland lake.

We note that the wings of time are tauig, 'dewy', dew being the signature of the day-night boundary, the counter of passing time, tomorrow-today-yesterday.

Denn

One more easily overlooked word deserves our attention: denn, 'because' or 'since', in the first stanza, at the beginning of line 5.

Ach, auf der Freude sanftschimmernden Wellen

Gleitet die Seele dahin wie der Kahn;

Denn von dem Himmel herab auf die Wellen

Tanzet das Abendroth rund um den Kahn.

Oh, on the joy of softly shimmering waves

The soul glides like the boat;

Because down from Heaven on to the waves

the red of the evening dances around the boat.

The word denn links the third line-pair with its predecessor, which had transformed the boat into a metaphor of the soul gliding upon the joy of the softly shimmering waves, Denn, 'because', the third sense-unit tells us, the sunset comes down from Heaven. The sunset is not a passive phenomenon, it is an active cause of the Freude des Himmels und Ruhe des Haines, the 'joy of Heaven and peace of the grove' – the sunset waves to us, it dances on the waves and the reeds whisper.

Entschwinde

Readers in a hurry will scoot over the third stanza and think it some lament on the 'time flies' theme: carpe diem, 'seize the day', we are all going to die sooner or later.

Ach es entschwindet mit thauigem Flügel

Mir auf den wiegenden Wellen die Zeit.

Morgen entschwinde mit schimmerndem Flügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Bis ich auf höherem stralenden Flügel

Selber entschwinde der wechselnden Zeit.

Oh away with dewy wings

time flies from me on the cradling waves.

Tomorrow on shimmering wings

May time flee as yesterday and today,

Until I on higher radiant wings

Myself escape changeful time.

Careful readers, their index fingers slowly tracking along the lines across their screens, are brought to a stop by entschwinde, 'disappear', 'flee'. With the 'time flies' theme in our heads we were expecting wird entschwinden (future, since we are talking about tomorrow) or entschwindet (present as future).

What Stolberg gives us is entschwinde, which is the third person present subjunctive or the imperative of the verb. Your translator has already represented this as 'May time flee as yesterday and today' and thus already given the game away: Stolberg is not looking forward to getting his wings and fluttering off to heaven, not at all. He is wishing for more joyous sunset days such as the one he has experienced today and yesterday. Time does indeed fly – he notes that in the first line of this stanza, with regret Ach. But in the next line pair, as noted, he wants time to fly tomorrow as it has done today.

The wonderful sunset as he presents it is not a static scene, it is a process, as we noted in his use of the word erröthend, 'reddening'. As such the phenomenon is embedded in time. He cannot wish time away and still experience the glory of that sunset.

The final entschwinde is the simple first person present indicative of entschwinden, agreeing with the subject ich.

The use of the subjunctive entschwinde is quite deliberate – no German writer would write this as a mistake – and it is crucial to the interpretation of the poem. Unfortunately, so great is the anticipation of the 'time flies' theme that it seems to overwhelm even people from whom you would expect more accuracy.

[Dittrich 217], for example, writing the Lieder section of Walther Dürr's Schubert Handbuch misquotes stanza three, writing entschwindet instead of entschwinde, thus sabotaging Stolberg's careful point. Whilst we are on this subject we note that she also quotes the first stanza and in doing so sprinkles some commas into the second line: Gleitet, wie Schwäne, der wankende Kahn. These commas can only be tolerated by someone with a tin ear. She also mutilates Stolberg's metaphor wie der Kahn by changing it into the ridiculous wie ein Kahn. She is not alone: CD booklets around the world are decorated with such mutilations and more – let's not even mention the internet. Keep cheerful!

Leopold von Stolberg

Although some critics, pure in heart, like to imagine that a poem should trot along on its own, without the need for biographical crutches, sometimes the author's biography can add flesh to the bones.

In the case of Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen we are invited into Stolberg's biography by the author himself, who dedicates the poem für meine Agnes, 'for my Agnes'. This addition is not present in the Schubert title.

We criticise others for imprecision and therefore have to hold ourselves to a high standard here, for the phrase is not, strictly speaking, a dedication, where we might expect something like An meine Agnes.

Grammar comes to our aid in understanding what Stolberg has done here. An meine Agnes would need to follow a full stop or stand independently on its own line. What Stolberg actually wrote included Agnes in the title: Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen, für meine Agnes. The comma avoids an ambiguity: without it we would be singing the song for Agnes, with it we are told that the song itself is for Agnes. Because it is not a dedication it is a remarkably warm, loving attribution – 'my Agnes' – it is a message to her and as such almost voyeuristic for the reader. Who was this Agnes?

Agnes von Witzleben

She was Henriette Eleonore Agnes von Witzleben (1761-1788). She and Stolberg married on 11 June 1782. The marriage produced three children, all of whom would live to good ages for the time.

Agnes was highly talented in her own right: she was musical, artistic and a published author. Despite all this talent, Stolberg tells us that she exhibited an almost childlike simplicity and purity, something which clearly appealed to Stolberg's piety.

Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen, für meine Agnes seems to have been written some time in the first half of 1782, shortly before Stolberg and his Agnes married. We have no direct information about the writing of the poem.

Their marriage was blissful, but only lasted six years. Agnes died on 15 November 1788. Stolberg's description of the last days of their time together illuminates the message of the poem that he sent to his Agnes just before their wedding:

After I returned on 21 September [1788] from Neuenburg she blossomed like a rose. I have never seen her so healthy or so beautiful. I was indescribably blessed, oh [ach!] both of us felt so happy. I myself was also completely well, as I had not been for years. The sweet children around us flourished, the house was filled with peace and our hearts with joy. One day followed the other quickly and at the end of the week we laughed in amazement at the flight of time [Flug der Zeit]. She was happier than ever and after each short absence of an hour would skip like a deer to greet me. She was more loving than ever. She spoke daily, often and with sincerest feelings, of our happiness that had no earthly equal.

[...]

In the last seven weeks of her health she was incapable of any unfavourable sentiment. Nothing could cloud the light in which the heaven of her heart was reflected [sich der Himmel ihres Herzens spiegelte].

Janssen 209f. Translation ©FoS.

The epiphanic moment

In 1780, two years before writing the poem, however, Stolberg wrote an essay that reveals that the imagery of his poem had formed in his mind even at that early time. The essay was entitled Über die Ruhe nach dem Genuß und über den Zustand des Dichters in dieser Ruhe, 'On peace after pleasure and on the condition of the poet in this peace' – albeit a rather mysterious title for the modern mind.

This is what the condition of peace after pleasure is like. The soul is like a fine, cheerful, cool evening. The sun has set; a glowing, but ever more softly shadowed evening red covers the sky; it seems as though Nature is resting; but even in this moment she is working; with quiet, invisible growth the plants are increasing in size and drink the dripping dew, in order to be even more beautiful when they unfold. Quiet, barely sensed perceptions develop in the soul of the resting person, drunk on joy. Just as stars appear one after the other out of the decreasing redness of the sky, so one perception after another wells up. Such moments are fruitful moments of reception for the soul of the poet.

Promies 320f. Translation ©FoS.

What an eery precursor of the language and imagery of the later poem! Once we have got past our initial confusion at this gigantic metaphor, we realise that this is merely an image of the state of mind of the creative artist at stasis, intoxicated with joy and in the process of experiencing what we moderns might call a Joycean 'epiphany', the transition to a heightened perception.

Not only that, but Stolberg tells us a few pages later that these moments can occur not only in the present but in the past and the future – the 'joys of remembering and hoping', as he puts it in the essay or as his puts it in the Lied:

Morgen entschwinde mit schimmerndem Flügel

Wieder wie gestern und heute die Zeit,

Tomorrow on shimmering wings

May time flee as yesterday and today,

So, the poem is for his Agnes, not simply dedicated to her. It tells her of the source of his inspiration, intoxicated with joy in the fruitful moments of poetic reception. Agnes is clearly as much of a partner for him as she is a wife in the dynastic 18th century sense. We can understand what a loss her early death much have been for him.

He married again on 15 February 1790: Countess Sophie Charlotte Eleonore von Redern (1765-1842). In the thirty or so years they had together before Stolberg died in 1819 they produced 14 children, ten of whom reached adulthood. Their first child, a daughter, they christened Julie Agnes Emilie.

Franz Schubert

Franz Schubert would not have been aware of all the twists in the maze we have followed in our discussion Stolberg's poem. But is is clear when we listen to his composition that he not only understood the metrical subtleties of the poem, but he also grasped the meaning of the poem as few have done since.

The song composer has to read slowly, attentively and precisely – a broad brush is not suitable for this task. We can see in many of his other song compositions that he was quite prepared to cut or amend texts to improve them.

In Stolberg's poem he enhances the parallelism and overlaying of the sense-units, the line-pairs, by repeating the second and third ones in each stanza – adding a further level of reflection, as it were. Each stanza is executed in a minor key, but then, quite remarkably, the last line of each stanza shifts to a major key, and the joy of Stolberg's epiphanies breaks through. In the last line of each stanza Schubert adds his own magic: he takes the long syllable of the first dactyl and stretches it out, letting the voice glide over the underlying piano 'waves' for almost two bars. Respect!

There can not be the slightest doubt that Schubert understood well what Stolberg was at, even without the advantage of having read the present explanation.

There is also for Schubert a biographical component to the story of the composition of this song.

1823, the year of its composition: arguably the worst year of Schubert's life. The immense waste of time and effort that was the composition of Die Verschworenen, D 787 and Fierrabras, D 796. The failure of Rosamunde, D 797. The composition of Die schöne Müllerin (who cared? it would be another 33 years before the cycle was performed in its entirety). His closest friends were missing: Schober left that year to tread the boards in Breslau; Joseph von Spaun was in Linz, pursuing his career; Johann Senn was in exile in Tyrol.

Oh, and the headaches, fevers and ulcerations turned out to be syphilis – at that time almost a death sentence – meaning that a month of his autumn was spent on the dedicated syphilis ward of the General Hospital in Vienna being poisoned by mercury. His hair fell out and he had to wear a wig for a while.

Sometime in the middle of all this – all the illness and rejection and loneliness that he characteristically bottled up inside himself – he knocked off Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen, Stolberg's song for his Agnes, his soulmate, a joyful epiphany.

Performance

In the performance of Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Gerald Moore are the team to beat. Fischer-Dieskau wrote:

Perhaps this is the most pregnant of Schubert's many water studies, here certainly challenged by the uniqueness of the poem, which repeats two lines that are similar if not identical and thus creates a dreamlike mood. The song presents the most beautiful attractions of the Schubert lyric, namely the combination of voluptuous Austrian singability with all the instrumental advantages of the simultaneously composed piano works of his, such as here the 'Impromptus' and 'Moments musicaux'. The A-minor from the beginning of the song is maintained until the scene is flooded by the red of evening and Schubert illuminates it with the A-flat major. Nothing has been conceived that is so intimate and carefree, so warm-hearted and detached at the same time.

Fischer-Dieskau 216. Translation ©FoS. Fischer-Dieskau errs in his dating: the song was composed in 1823, the Moments musicaux were composed in a period between 1823 and 1828, the Impromptus were definitely composed in 1827.

Sources

As a rule only direct quotations from these sources have been attributed in the text. All translations ©FoS.

- Dittrich, Marie-Agnes. 'Lieder' in Dürr, Walther, and Andreas Krause. Schubert Handbuch, Kassel, Stuttgart, Bärenreiter, Metzler, 2007, p. 141-267.

- Fischer-Dieskau, Dietrich. Auf den Spuren der Schubert-Lieder; Werden, Wesen, Wirkung, Wiesbaden: F. A. Brockhaus, 1971.

- Janssen, Johannes. Friedrich Leopold Graf zu Stolberg, Freiburg im Breisgau, Herder'sche Verlagshandlung, 1877, 2 volumes.

- Promies, Wolfgang, 'Worte wie Wellen, Spiegelungen. Zu Stolbergs Lied auf dem Wasser zu singen, für meine Agnes' in Richter, Karl, ed.Aufklärung und Sturm und Drang, Stuttgart, Reclam, 2006, p. 308-324. [DE]

I wish to record my indebtedness to the late Professor Promies in shamelessly using many of his insights into Stolberg's poem from his interpretation. He departed on higher radiant wings in 2002, much too soon.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!