5 May 1799: A little local difficulty in Switzerland

Richard Law, UTC 2019-05-05 15:07 Updated on UTC 2019-05-08

The beginning of modern Europe

230 years ago, on 5 May 1789, the Estates-General in France convened in the Palace of Versailles in what can be regarded as the first political shot of the French Revolution. Two and a half months later, on 14 July – as every schoolchild knows (or ought to know) – the first real shot of the French Revolution was fired at the storming of the Bastille.

The crowned heads of Europe watched and waited, expecting the uprising to fizzle out. It didn't fizzle out at all, but developed an astonishing momentum, turning from a revolt into a revolution within days. Feudalism, the political system that had shaped Europe for more than a thousand years, was abolished at a stroke barely a month after the Bastille had been taken. With that, France became the second 'modern' state in the world – the first had been the United States in 1776.

The house of cards that was the Bourbon kingdom and all its aristocratic accretions crashed to the ground brick by brick and definitively so when Citoyen Louis Capet's head plopped into a basket on 21 January 1793.

The crowned heads of Europe and their underlings were even more shocked at the five years of murderous terror that followed the fall of the Bastille. From their great houses around Europe they could watch their serfs and servants labouring in their service – even the dimmest could now imagine what those nonentities might one day do to them, were they to rise up. There was understandable paranoia about the possibility of a homemade repetition of the blood-soaked revolution in France.

Paranoia

In France in the ten years after 1789 the country was in seething uproar with coups, counter-coups and uprisings. There was an understandable paranoia about spies and traitors within the country and the activities of exiled aristocrats outside the country.

The paranoid conviction of the French republicans that all the remaining feudal countries of Europe were out to get them had been reinforced early in the revolution: in 1791 when Louis XVI and his family had attempted to flee the country to support a counter-revolution and in 1792 when the Prussians and the Austrians launched a futile and ill-conceived mini-invasion at Verdun. The latter triggered the paranoia of an outraged Parisian mob to embark on a campaign of butchery of its supposed enemies in ways that would make the standard trip to meet Mme Guillotine seem humane.

That paranoia led to France adopting a policy of exporting its revolution to other countries, some of which were already struggling to cope with their own homemade revolutionaries. A policy of self-defence, as it were.

From that moment on, Europe descended into the almost twenty years of internecine warfare that only ended when Napoléon Bonaparte was finally defeated, exiled for a second time – this time safely to a blip of an island in the middle of the South Atlantic – and the Treaty of Vienna drew the line under those awful decades. Crowns returned to heads and thrones were warmed by aristocratic bottoms once more.

The first step in the French export attempts began in 1795. The strategy was to form a circle of compliant or subject states around France's borders, called republics in deference to the mother ship: the Cisalpine Republic in northern Italy, the Ligurian Republic in the north-west of Italy, the Cisrhenian Republic on the left bank of the Rhine and the one that concerns us today, the Swiss Republic.

The Swiss Republic – one more French satellite

We had some contact with the Swiss Republic in our piece about Grillparzer's love Heloise Höchner.

At that time Switzerland was not the peaceful, democratic country we know today – in fact, it wasn't even a country. The country and the peaceful democracy first came along in 1848. At the end of the eighteenth century, what we today call Switzerland was a complex patchwork of local aristocratic mini-despotisms held together by shifting alliances. It had also been scarred by the religious conflicts of the Reformation and in some places those wounds were still raw. At this time the main part of Switzerland was held together in the so-called Thirteen-Cantons Confederation.

Many Swiss found the idealised tenets of the French Revolution, aside from the bloodshed of its practical implementation, very attractive, particularly its universality of laws, rights and government. They looked to the French to help them carry out their Swiss revolution, the goal of which was the founding of the Swiss Republic.

At first, the French, with the help of some judicious subversion, found themselves welcomed almost without resistance in most parts of Switzerland. They and their armies swept almost unopposed from the French speaking cantons of the west across to the German speaking cantons of the east. Once the majority had fallen, the little pockets of resistance were easily – sometimes savagely – dealt with.

It was a nice dream, but it didn't take long for the Swiss to wake up and realise that the Swiss Republic was just a satellite of the French state, a satellite in whose decisions the natives had no say at all.

Encircling the Drei Bünde

For the French and the Swiss proponents of the Swiss Republic there remained one last problem: the area we now know as Graubünden, the Grisons.

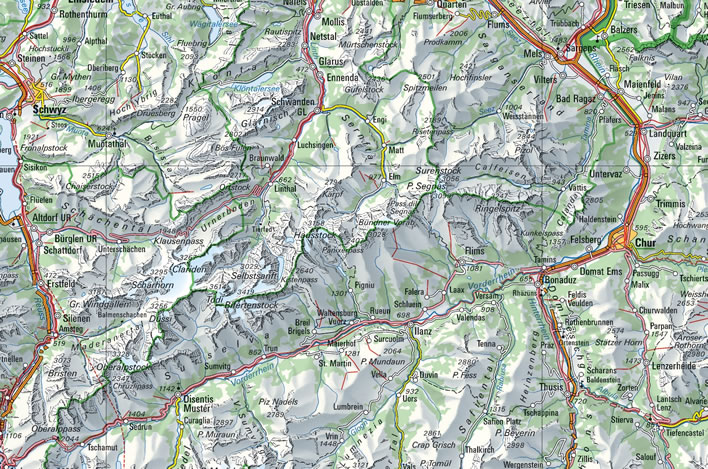

A map of modern Graubünden, showing the general area of the conflict in 1798/99. The area that concerns us particularly is the valley of the Vorderrhein, the Anterior Rhine, that runs roughly west to east from the Oberalp Pass at the bottom left to Chur at the middle right. Image: Swisstopo.

Looking from Ilanz up the valley of the Anterior Rhine towards Disentis (September 1997) and …

… looking from Ilanz down the valley of the Anterior Rhine towards Chur (May 1997).

Images: E-Pics, ETH.

This region was not part of the Thirteen-Cantons, but was held together in its own federation, the Drei Bünde, 'Three Leagues'. Each of the three 'leagues' was an association of Gerichten, jurisdictions, each of which represented one or more of the villages of a particular locality.

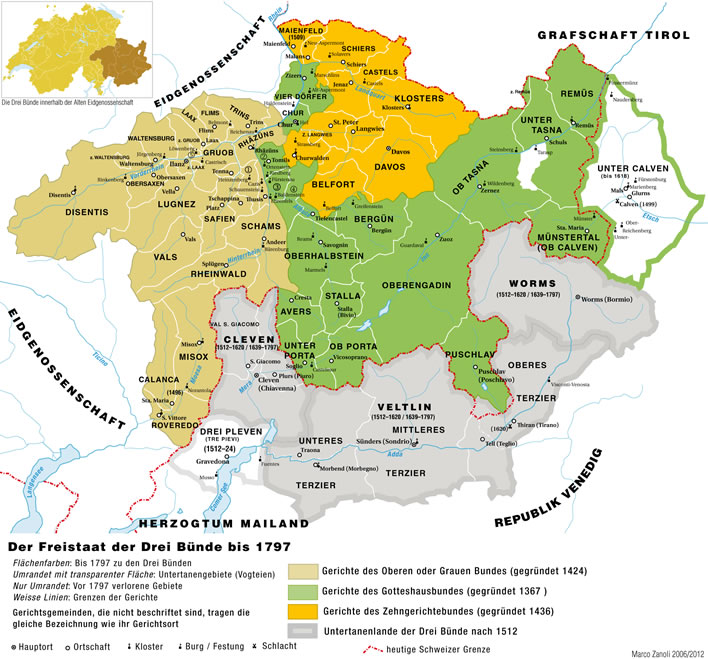

The Drei Bünde before 1797. The beige districts were part of the 'Upper' or 'Grey' League, the green were in the 'League of God's House', the orange formed the 'League of the Ten Jurisdictions'. The valley of the Vorderrhein runs across the top part of territory of the Grey League. The grey areas mark the subordinate territories on the Italian border. Image: Marco Zanoli.

Graubünden had suffered more than any other part of Switzerland in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) that followed the Reformation (1517-), a period so confused and violent that is has been given its own name: the Bündner Wirren, the 'Graubünden Turmoil'. We shall spare the reader this turmoil and the complexities of all the alliances that finally led to the creation of the Drei Bünde. There is only so much Swiss history that a non-Swiss person can digest at one sitting.

In March 1798 French troops with local help overran the territories of the Thirteen-Cantons and on 12 April 1798 the Swiss Republic was founded. The Drei Bünde had to decide. On their territory were many of the great alpine passes, now strategically linking the new republic with the French satellite state of the Cisalpine Republic – the French would not want to let that prize escape them.

Local weakness

Down the centuries the Swiss have been specialists in local autonomy, right down to the level of the village. Hand in hand with this local autonomy goes a fear of subservience, but therein lies the great paradox: when the great power, the great nation state comes calling, how can these minnows assert their independence against overwhelming force?

The traditional Swiss solution has been to form federations – Wir wollen sein ein einzig Volk von Brüdern, 'we want to be a single people of brothers' as Schiller put it in Wilhelm Tell when the founding Three Cantons were up against that world power, the Habsburgs – but even these groupings are ultimately no help against the great powers.

After the peace dividend that followed the Bündner Wirren, the Drei Bünde now found itself unarmed and undefended between the interests of two great states: the French wishing control over the passes as well as the integration of the Drei Bünde into their satellite Swiss Republic, and the Austrians, the old Habsburg enemy, who shared a border with the Drei Bünde and who wanted to block the expansion of the French, their old enemy.

The Drei Bünde was utterly unprepared for the French challenge, politically or militarily. Local autonomy is a wonderful thing, but now and again eyes and minds must be lifted above the local horizon to perceive the bigger picture and the greater issues.

It was clear to everyone who looked over that horizon that the people of the Drei Bünde were just the tiny grains of corn that passed between the millstones of the great European powers. They had no organized military, no weapons and – worst of all – no appetite for a hopeless fight. Even in the face of the threat of a greater subservience to an external power, every village and every association of villages feared becoming subservient to its peers. They were completely disunited.

Dithering in the middle

Out of this disunity in the Drei Bünde two factions emerged:

One faction was for the maintenance of the status quo, which in turn required the rejection of the Swiss Republic and of all the French overtures and threats to bring it about. Not surprisingly, this faction was supported by Austria, thus its Swiss supporters looked towards Austria to preserve it in its time of need.

The other faction was for the destruction of the status quo. They wanted to embrace the Swiss Republic and the administrative and legal reforms that it would bring. A breath of fresh air in the stifling stasis of the mini-despotisms of Switzerland. They, of course, were supported by France (and the other cantons who had let themselves be absorbed into the new Swiss Republic) and looked to the French to help dig them out of the ancient feudal swamp.

There was in fact a third faction, which we don't need to list explicitly because it is always there: the do-nothings. If the people sided with the French the Austrians would attack. If they sided with the Austrians the French would attack. Best do nothing, wait and see and hope the problem goes away.

For quite some time the do-nothings were in the majority, until 1797, when some serious news arrived: three 'subject administrations' of the Drei Bünde located along the border with Italy (the areas marked grey on the map above) threw in their lot with the new French satellite, the Cisalpine Republic. Suddenly the Drei Bünde was quite alone and quite unprotected between the two millstones. The problem had not gone away, just got worse.

What's the Swiss solution in such situations? Let's have a referendum!

On 6 August 1798 the towns and villages making up the Drei Bünde took part in a referendum. As is always the case with such big decisions, the referendum decided nothing, merely reflected the divisions in the people. That is always the case with referenda – there is no point holding them unless they are going to give the required answer.

Out of 61 communities, 34 voted to retain the status quo with the assistance of Austria, that is, they voted against the French; 11 voted for the French and for an integration in the new Swiss Republic; and 16 voted to put off the decision – to wait and see, in other words (where would we be without the wait-and-see-ers?) and hope that their neutrality would get them through. That is, there was a majority of 7 communities – 11 percent – in favour of holding out against the French.

A further feature of a referendum is important here: it advertises to both allies and enemies what the mood of the country is – they don't need spies to report on this. Austria now knew what a weak and divided ally it would have; France knew what a weak and divided enemy it would have.

The one thing that the referendum did not clarify was just how those 34 communities who had voted against the French and the Swiss Republic were going to be able to implement their gesture of defiance.

Disentis and the Cadi

Furthermore, the distribution of opinion amongst the members of the Drei Bünde was not homogeneous: a particular bastion of resistance was present in the so called Cadi, the region that stretched from around Disentis down the valley of the Vorderrhein, the 'Anterior Rhine' to Brigels.

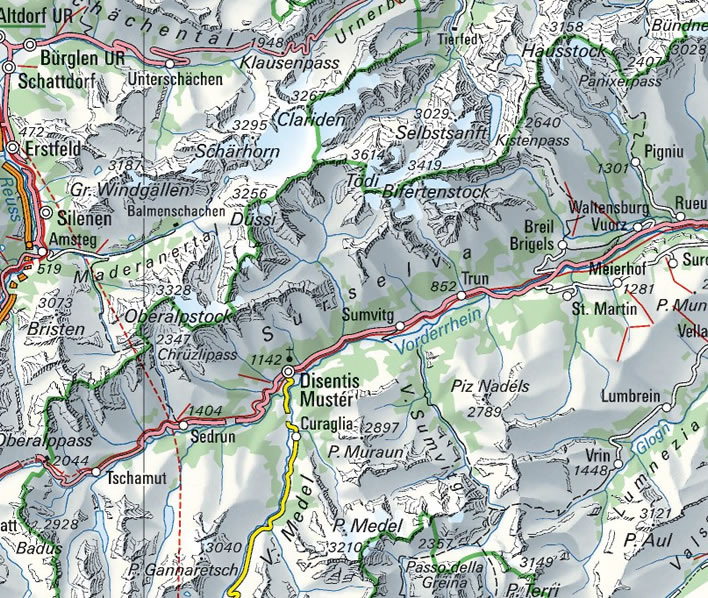

The area of the Cadi shown on a modern map. The territory of the Cadi stretched from the Oberalp Pass (bottom left) down the course of the Vorderrhein. The principal settlements were Sedrun, Disentis (the capital), Curaglia, Medel (not shown), Sumvitg, Trun, and Brigels. The borders followed the peaks and ridges of the surrounding mountains (green lines). The farthest extent down the valley was a border just beyond Brigels. Image: Swisstopo.

A view from Waltensburg up the valley towards Disentis. The area from Brigels (the village with lake middle right) up to Disentis constituted the Cadi.

A view from Brigels down the valley towards the Rheinschlucht (the white mass in the distance) and Chur beyond it. Both images September 1997: E-Pics, ETH.

Disentis was the home of an important abbey and was located close to the end of the Oberalp pass that came down from the international crossways at the Gotthard Pass in Urseren. From Disentis the Anterior Rhine flows down the valley towards Chur, the capital of Graubünden.

Disentis (middle), looking from above the base of the Oberalp Pass down the valley (October 1999). Image: E-Pics, ETH.

In September 1798 a meeting of the Council of the Drei Bünde was held in Ilanz, a town almost equidistant between Disentis and Chur.

Pursuant to the majority outcome of the referendum the previous month the Austrians were asked for help. A month later, on 17 October, two Austrian generals arrived in Chur and agreed to station sufficient troops at all the borders and passes to defend the Drei Bünde. On the following day Austrian troops arrived in Graubünden over the Luziensteig and into the Engadin.

With that move, the Drei Bünde abandoned its neutrality and became a declared enemy of the French. The waiting was over and the game was now on.

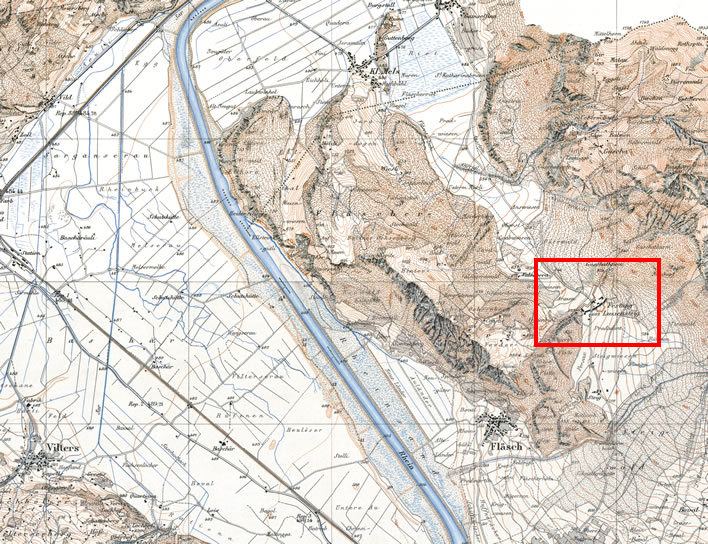

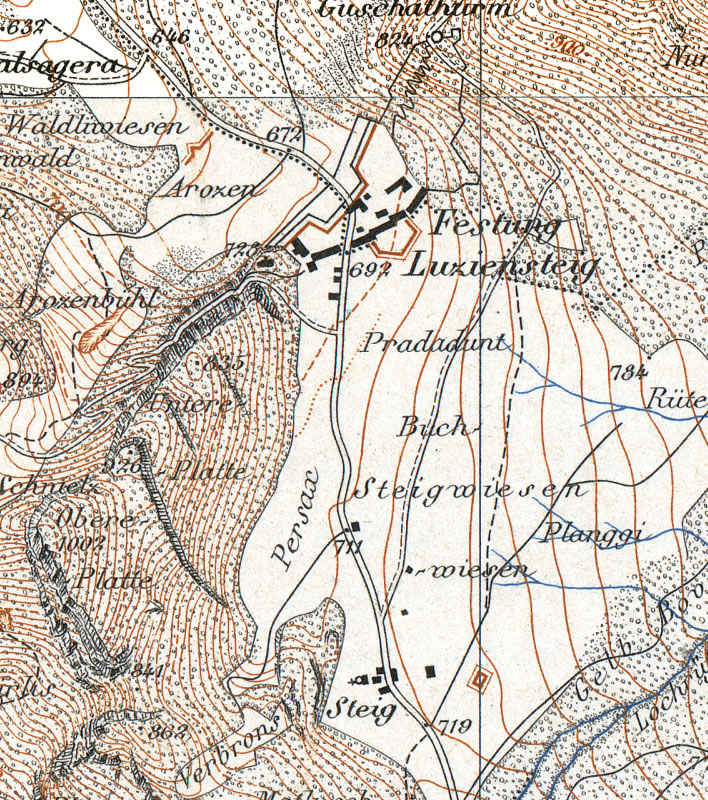

The pass road over the Luziensteig (sometimes written Luzisteig, the name derived from Saint Luzius von Chur) has existed for thousands of years. In the late Middle Ages there was a defensive rampart (a Letzi) here that marked the border between the territory of the 'League of God's House' and that of the 'League of the Ten Jurisdictions'. During the chaos of the Bündner Wirren the fortifications (and the customs post) on the pass grew in importance. The fortress maintained its role through the Second World War and into the Cold War era. Base images: Siegfriedkarte Swisstopo. [Click on the top image to open a large version in a new tab.]

Note: The Topographischer Atlas der Schweiz, the 'Siegfriedkarte', was first published in 1870. It is therefore not contemporary with the events of our subject, but still shows something of the Switzerland that existed before the massive changes to population and landscape that occurred in the 20th century. The 'Dufourkarte', the Topographische Karte der Schweiz is slightly older (1845-1865), but is unsuitable for web use.

Im Gesicht von Luziensteig, 'In the face of the St Lucian Ascent'. 'Groupe d'hommes se préparant à manger sur un chemin qui longe la falaise de Luziensteig, surplombée de sapins', 1827. This image tells us nothing about the Luziensteig – is suggestive, though, of its fame. Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

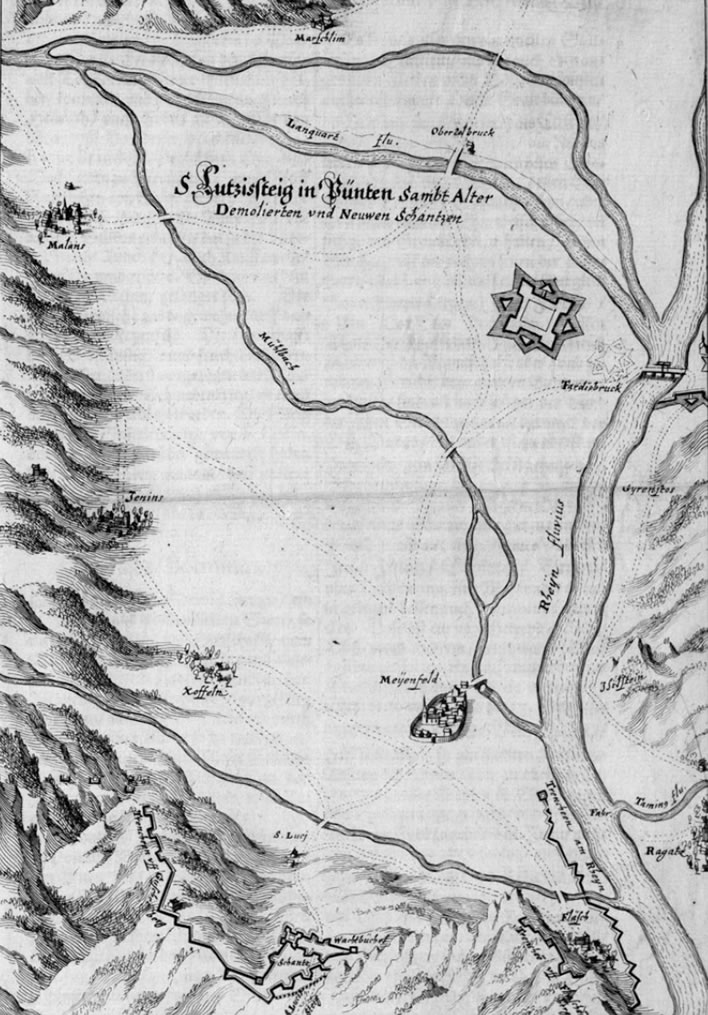

Even in 1654 there was an extensive fortress on the Luziensteig [at the bottom of the map]. S. Lutzissteig in Pünten sambt Alter Demolierten und Neuwen Schantzen, 1654. [NB: north is down, south is up.] Carte de la région de Maienfeld tout au nord des Grisons, le sud étant en haut, la rivière de Landquart, horizontalement en haut, le Rhin, verticalement à droite, ville de Maienfeld au milieu et le col de Sankt Luzisteig en bas, protégé par des muraille, menant au Liechtenstein. Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

Preparing for war

The core of the resistance to the French in the Cadi now showed itself.

In this region there were former mercenary officers who had served in the army of the French King. In the poverty-stricken alpine regions, mercenary service was often the only future for the young men of the region. Some may have been among the few survivors of the heroic debacle during the storming of the Tuilleries by an incensed mob aided by the French guard on 10 August 1792, many would have known personally the widows and orphans left behind.

The attack on the Tuilleries led to the bestial massacre of many of the Swiss Guard, who were there to protect the French king. The Swiss did not desert their posts but did what they were hired to do, they fought on – pointlessly as it turned out, since the King they thought they were defending had already left by a back door and in effect given himself up to the revolutionaries. The fleeing Louis omitted to relieve his Swiss Guard from their obligations to protect his non-existent self.

Somewhere around 600 Swiss were slaughtered in that heroically pointless defence; 246 more were captured, sentenced to death and butchered in one way or another in the following weeks. 217 managed, with local help, to escape. It should not surprise us, therefore, that the homeland of so many Swiss mercenaries had no love for their former revolutionary opponents.

The former Swiss mercenaries were well trained and tactically and strategically skilled. Whereas in many of the other regions of the Drei Bünde the common people were happy to let the Austrians do their fighting for them, the men from Disentis could count on the fierce engagement of the local population in any conflict. They seized whatever lay to hand that could be used to kill French soldiers. This time round, they would be the storming mob.

The Cadi formed its own war cabinet, unlike the other communities, which were in military disarray – once more Swiss local autonomy in action. They acquired powder and lead from Bregenz, 150 rifles from Swabia, even two cannon and an artillery instructor to train the twenty men in the company; they also formed two Jäger companies of the sort that had been so successful in the Tyrol; and, most importantly, they also formed a Landsturm, a militia infantry, who acquired whatever weapons they could get their hands on. The militia could be raised in minutes by the ringing of the church bells. By great good fortune there was a false alarm on 17 October which tested their mobilisation system and demonstrated that their theoretical plans really worked in practice.

Following the first military deployments on both sides at the end of 1798 there was a winter pause until the arrival of spring made war feasible once more. During the months of inaction the forces in the Cadi gave firing practice to the militia infantry and military training to the new Jäger, small, mobile companies which could work effectively in mountainous terrain. A deputation met with the French commander in charge of this sector, Louis Henri Loison (1771-1816), who gave them his word of honour that he would give notice of his attack.

Spread thinly

By the beginning of March 1799, Austrian troops were dotted around key positions in the Drei Bünde and the French had positioned themselves for their attack. The disposition of the Austrian troops in the area was extremely foolish. The overall commander, Heinrich Joseph Johann Graf von Bellegarde (1756-1845), despite his personal knowledge of the terrain, ended up with far too few troops to defend the territory adequately, a problem which he made worse with a nonsensical distribution of those troops he did have available.

Bellegarde's original estimate had been that 14,000 Austrian soldiers would be needed for the defence of Graubünden, with the help of 18,000 local militiamen. In the end, under pressure to supply troops for the defence of the Tirol and the important area around Bregenz, he had barely the half of that available and of militiamen somewhere between three and four thousand. The limiting factor on his troop strength was not simply availability but also the difficult logistics of ensuring the supply of materials and rations in this complex terrain.

The Austrian troops were scattered in small detachments throughout the territory, each detachment too small to resist anything but the most feeble attack. They seem to have been stationed more with the aim of the psychological assurance of Austrian commitment for the locals. When the French attacked, the Austrian forces were taken by surprise and were unprepared for the sudden transition from psychological support to armed combat.

Just to make things worse for themselves, the Austrians changed their command structure just before hostilities commenced. Bellegarde took command of the troops in the Tyrol and the command of the troops in Graubünden was given to Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze (1739-1799). The respective staff officers were also replaced. Even worse, Hotze was repeatedly reminded that his principal concern was the defence of the territory around Bregenz, not holding Graubünden.

The lower valley falls

The fate of the Drei Bünde was decided in two hectic days, 5 and 6 March 1799, when the French launched an attack at each end of the valley. Each attack was, in fact, two attacks from slightly different directions.

At the lower end of the valley on 5 March the French General André Masséna's (1758-1817) troops attacked the Austrian occupants of the fortress of the Luziensteig near Malans, about 25 km north of the capital, Chur. The defence of the fortress was bitter, but it was finally overrun that night.

The Luziensteig is a fortification that is still being used and actively developed by the Swiss army. This is an aerial photograph from 1963. The noticeable area of land on the Swiss side corresponding to the sightlines from the fortification was cleared of trees a long time ago in order to offer an attacker no cover. Image: E-Pics, ETH. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

The second aerial photograph is from 1987, nearly twenty-five years after the previous image, and shows the extensive development of the fortress during the Cold War period. Its current main role is as an army training facility and firing range. Image: E-Pics, ETH. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

By the morning Masséna had captured the fortress and with it 800 Austrian troops. The poor organization of the defence in the vicinity of the fortress allowed it to be surrounded on all sides, leaving the outcome of the attack as a certain win for the attackers.

Successful generals don't hang around: Masséna pressed on up the Rhine valley towards Chur. There he was even able to capture a key commander, General Franz Xaver Freiherr von Auffenberg (1744-1815), who had returned there during the debacle of the Luziensteig. Not only was he captured, the French took many prisoners and were able to acquire the entire artillery, supplies and provisions of the Austrian force, which had been stockpiled in Chur.

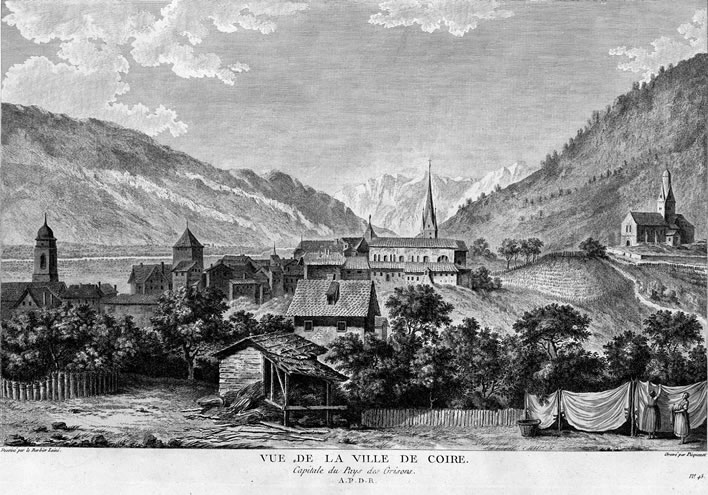

Coire, Capitale des Grisons, 'Chur, capital of the Grisons/Grubünden', 1730. 'Vue de la ville de Coire dans son environnement montagneux, entourée de sa muraille.' Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

Vue de la ville de Coire, 'View of the village of Chur', in Tableaux topographiques, pittoresques, physiques, historiques, moraux, politiques, littéraires, de la Suisse, 1780-1788. We now go from the city walls of the previous engraving to the rural idyll of sheds and washing lines, making us wonder whether this is the same place. The mountains around Chur are much more accurately represented, though. Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

It was the bad luck of the Drei Bünde that the man in charge of the Austrian forces in this theatre was the useless Auffenberg, who would be thrown out of the Austrian army in disgrace six years later after a series of crucial defeats caused by his incompetence. In contrast, his French opposite number, André Masséna, became one of the greatest commanders in European history. The Austrians had put the defence of the Drei Bünde in the hands of a dolt; the French its conquest in the hands of a military genius.

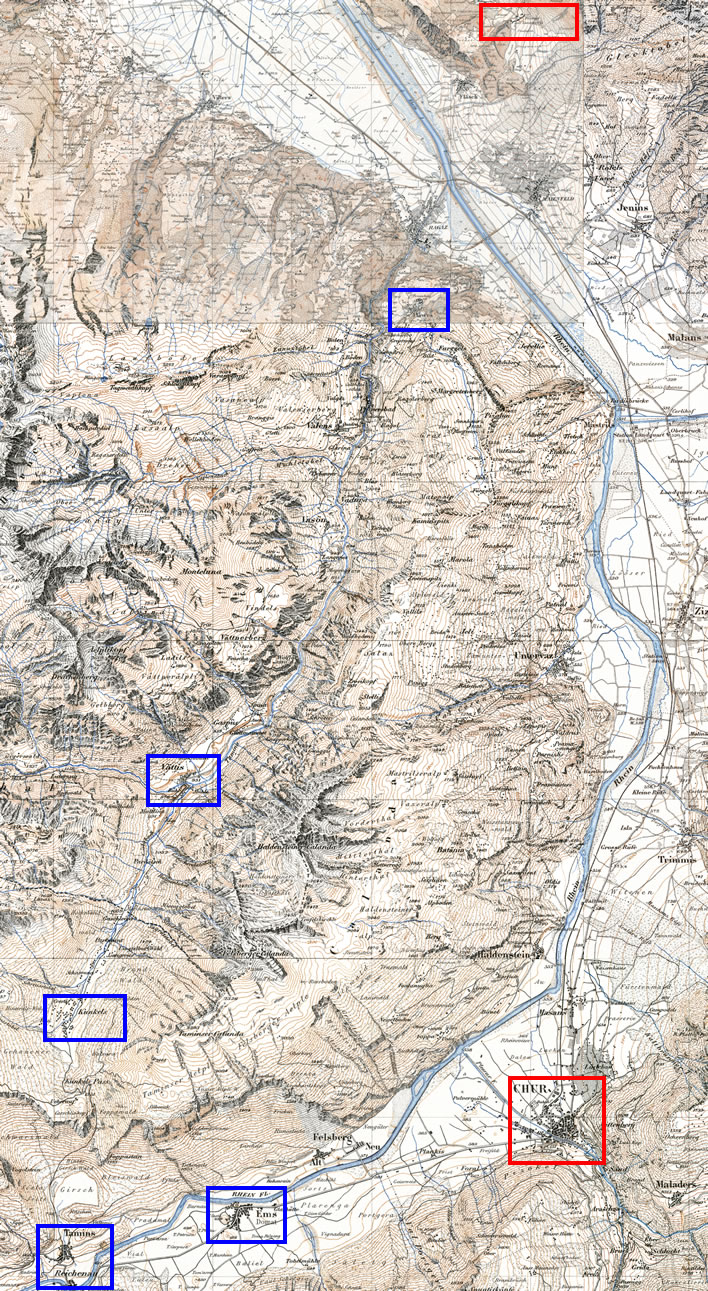

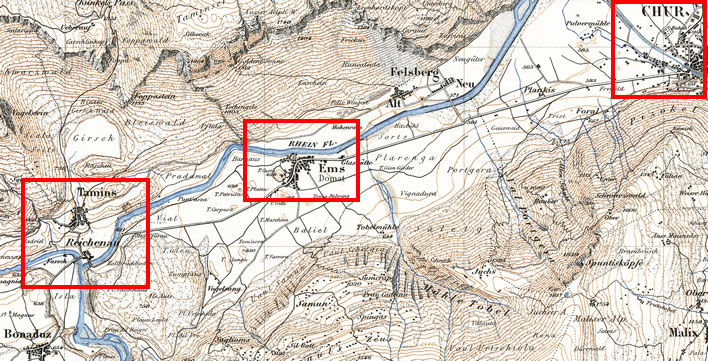

The two-pronged attack on the lower valley. The red rectangles mark Masséna's activities: top at the Luziensteig fortress; bottom in the capital, Chur. The blue rectangles mark Demont's route: Pfäfers, Vättis, Kunkels Pass, Tamins and Reichenau, Ems. Base image: Swisstopo, Siegfriedkarte. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

The second component of the French attack on the lower end of the valley was launched at the same time that Masséna had taken the Luziensteig. Joseph Laurent Demont (1747-1826) took a cross country route from Pfäffers and Vättis over the Kunkelspass. His troops overran the hapless Austrians posted to defend the pass and marched on to Tamins, which he captured along with the two bridges over the Rhine.

An aerial photograph of the Kunkels Pass in the Taminatal taken in 2003. Image: E-Pics, ETH. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

The perpendicular aerial view suppresses the narrowness of the pass. This an aerial photograph from June 1986 showing the steep-sided valley running from Oberkunkels (bottom) to the village of Vättis (middle). In earlier times an invading army marching in good order down a narrow gorge such as this would have been chopped up finely by Swiss peasant forces. The fact that Demont could take this route and encounter only the slightest resistance from a few lonely Austrian soldiers is a sign of the failure of will that beset the Swiss at that time. Image: E-Pics, ETH.

A soldier's-eye view of the Kunkels Pass from around 1930. Image: E-Pics, ETH.

The view of Tamins when descending from the Kunkels Pass. This photograph was probably taken in the late 1940s. Image: E-Pics, ETH.

Demont's further advance was blocked in Ems by energetic defence from the Austrians and the local militia, but the control of the bridges he had acquired was crucial – the Austrian forces in the upper Rhine valley to the west were now cut off from those in the valley of the Hinterrhein 'Rhine Posterior'. It was during Demont's attack that Auffenberg had set off to regroup the troops on his right flank, only to be captured by the French.

Brief success

Whilst all this was going on at the lower end of the valley, at the upper end around Disentis, General Loison, on 4 March, chivalrously announced his impending attack to his enemy, honouring his promise, and bade them to put down their arms. His troops set off from the snow-covered Oberalp pass. His first combat contact with the Swiss was with a half company of Jäger posted in among the old ruins of Pontaningan. After a skirmish the Jäger fell back in good order to Disentis, having fulfilled their task.

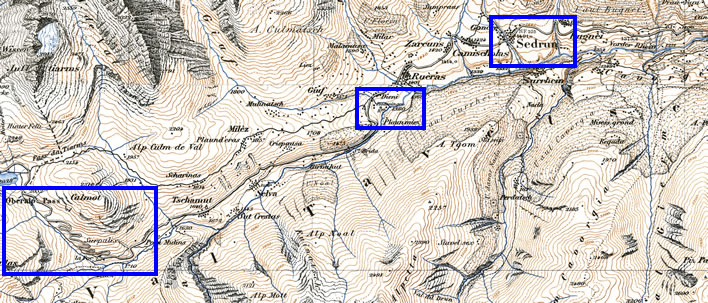

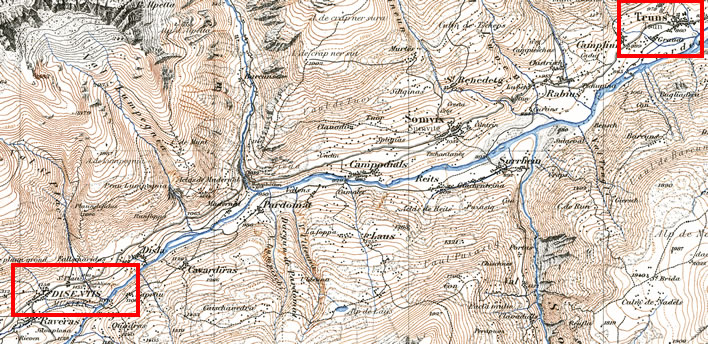

Loison's route from the Oberalp Pass (bottom left) via Pontaningan, where he encountered the Swiss Jäger company, to Sedrun. Image: Siegfriedkarte Swisstopo. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

The Oberalp Pass just to the east of Sedrun and Disentis in an image from 1934. The smooth route that follows the flank of the Calmot above the road is the relatively modern railway line. Image: E-Pics, ETH. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

The French then overran Sedrun. Not only did they plunder and damage the church there, they took the chaplain and the priest's brother prisoner. On the march to Disentis the two prisoners for whatever reason were clubbed to death by the French.

A photograph of Sedrun looking up the valley towards the Oberalp Pass, taken some time before 1975. Image: E-Pics, ETH.

Loison's career was blighted by his inclination to allow his troops to plunder as an instrument of warfare; despite his courtly French politeness in dealing with the upper strata of his enemy, he seems to have had little concern for the common people. That evening, he and his troops camped in Mompé-Tavetsch.

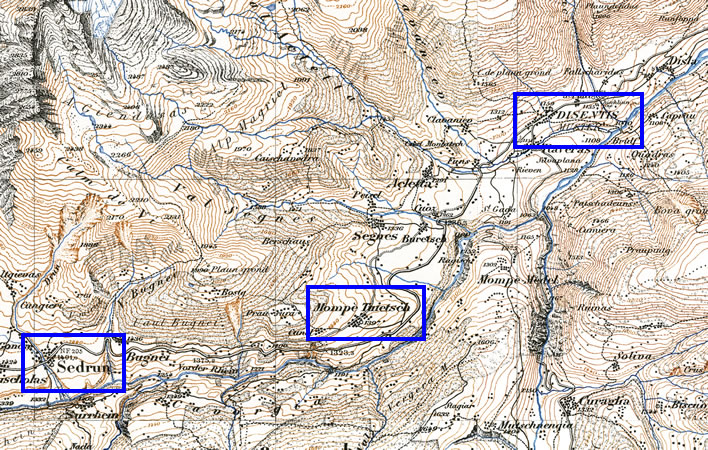

Loison's route from Sedrun via his camp at Mompé-Tavetsch to his engagement with the Swiss in Disentis. Image: Siegfriedkarte Swisstopo. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

In Disentis that night the preparations for the arrival of the French were put in place. The news of the murder of the two Sedrun captives aroused tremendous anger. The result was that when Loison's forces arrived on the morning of the 7 March, the Cadi troops were well prepared and highly motivated.

Loison had seriously underestimated his opponents. They had stationed a Jäger battalion on a nearby hill called Muntatsch, where they would be able to observe the approach of the enemy and attack the rear and the left flank of the French troops. The militia had taken position on a hill to the west of the abbey, also on the left flank of the attackers. A company of Austrians were positioned at the entry point into Disentis. They would bring Loison's column to a halt, when it would be attacked on the flank.

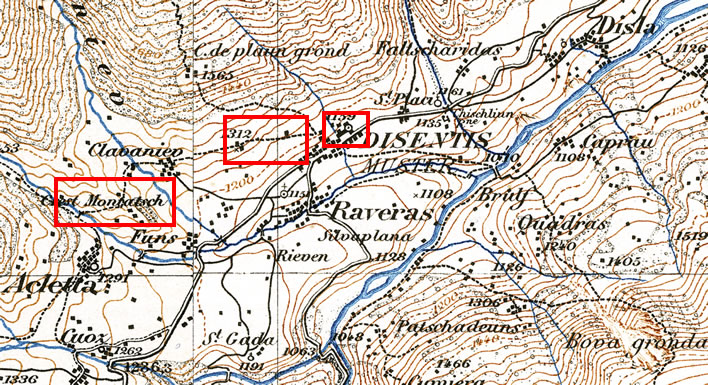

The engagement between the Swiss and the French in Disentis. The Swiss had positioned their Jäger on a spur of land, Muntatsch (left), and their militia infantry on the slopes of the hill (middle left) to the west of the abbey (centre). Image: Siegfriedkarte Swisstopo. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

For some reason – perhaps contempt for his humble opponents – Loison had not carried out a reconnaissance of the situation.

At the moment of his arrival the Swiss militia's position on the hillside next to the abbey was obscured by mist. When the French arrived at the Austrians blocking the entrance to the town, the defenders fell back in good order to the other side of the village. The French, made careless by this easy success, marched towards the abbey. The militia fell upon the French left flank and rear with extraordinary anger and clubbed and hacked any French soldier down whom they encountered.

A photograph of Disentis from the air, taken in 1925, the village still uncluttered with modern expansion. The abbey can be seen on the right. The steep meadows to the left of the abbey where the militia troops were positioned is clearly visible, as is the noticeable spur of Muntatsch, where the road turns sharply to the left. Image: E-Pics, ETH. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

The French were caught off balance by this surprising manoeuvre and attempted to retreat. The Jäger company now opened fire on them from the rear and the retreat turned into a rout. The French were pursued on foot and were allowed no time to consolidate. They were driven back to the Oberalp in disarray. The most reliable account puts the French losses at 150 dead and 30 wounded. The wounded were taken to the abbey, where they were treated extremely well by the monks.

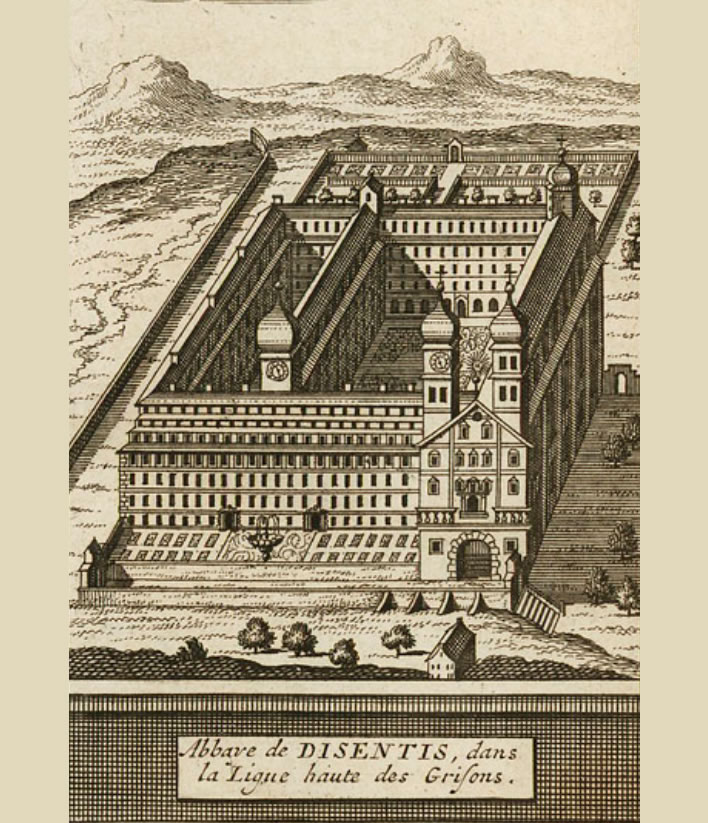

Abbaye de Disentis, dans la Ligue haute des Grisons, 'The abbey of Disentis in the Upper League of Graubünden', 1730. Bâtiment rectangulaire de l'abbaye de Disentis surmonté de ses quatre clochers. Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

As with the attack on the lower valley, the attack on the upper valley had a second component. There it had been a remarkable success, here it turned into a shambles.

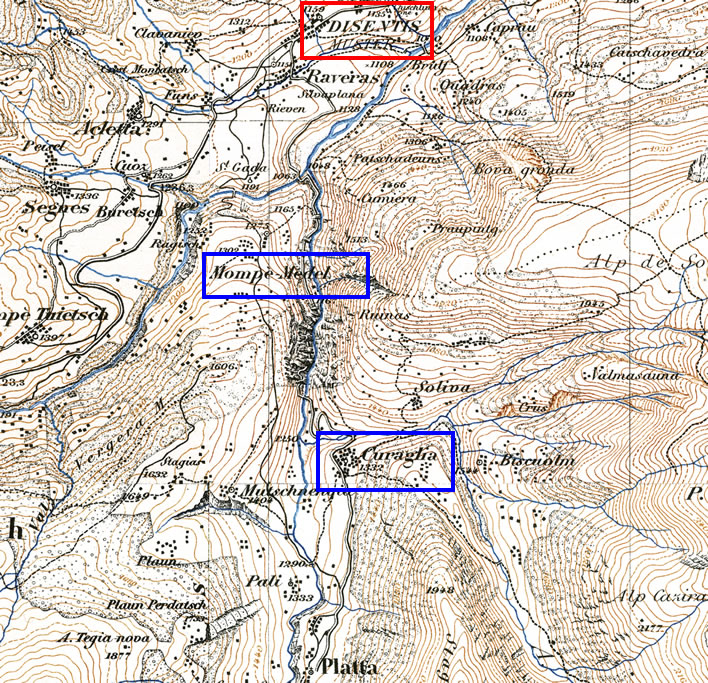

The route of the French troops arriving from the Piora Pass in the south. They wasted time sacking the village of Curaglia, turned back at Mompé-Medel and retraced their steps. Image: Siegfriedkarte Swisstopo. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

French troops came from the Leventine valley in northern Italy over the Piora pass. The Austrian guards were easily overpowered, but for some reason the unit spent a long time plundering and making a nuisance of themselves in the village of Curaglia. By the time they arrived in Mompé-Medel they were too late to assist anyone, their colleagues having already retreated back to the Oberalp pass. They therefore did the only thing that was left to them, turned back to Medel and retraced their steps over the Piora. The Grand Old Duke of York, indeed, French style.

The French attack on the upper end of valley had failed; its first component through the arrogance and carelessness of the French attackers and the serious minded preparations of the defenders, its second component through stupidity and incompetence.

For some reason Loison was promoted after his exploits in Graubünden – perhaps he was one of the golden aristocrats who did well in the army as a result of his position, even after the revolution. Until, that is, Napoléon sorted them out, too, with the introduction of a military meritocracy.

Capitulation

The jubilation in the Cadi at their win over the French lasted only a brief moment. The news arrived that General Masséna had defeated the Austrians around Chur and captured their commander and that Demont and his troops were already working their way up the valley towards Disentis.

A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, we say. Thanks to Masséna's and Demont's daring leadership, the link at the lower end of the valley and the region's capital, Chur, had been snapped apart with hardly any effort: the rest of the chain was now useless.

How could the upper valley continue to exist? The French were now in control of the other ends of all the passes to Italy. All trade with the rest of Switzerland and the wider world was now blocked. Even if the French were to do nothing more militarily, the region of the Cadi would wither away.

An aerial view from Tavanasa (opposite Brigels) up the valley towards Disentis, effectively the area of the Cadi. The next village on the Anterior Rhine is Trun, followed by Sumvitg and then Disentis in the distance. Image: E-Pics, ETH.

Swiss democracy once more played its role. A Landsgemeinde, a 'citizens' assembly' was called together to debate the simple issue: fight on or sue for peace.

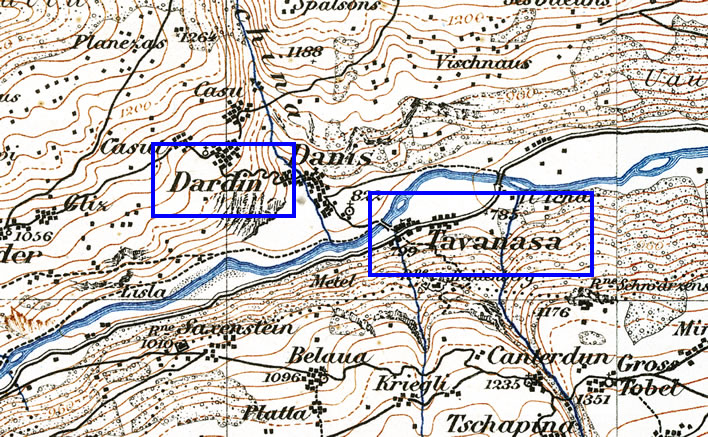

The decision was in fact easy, since, given that the rest of the Drei Bünde had now collapsed, military resistance would lead to obliteration. A delegation was therefore sent to meet up with Demont. They met close to the village of Tavanasa.

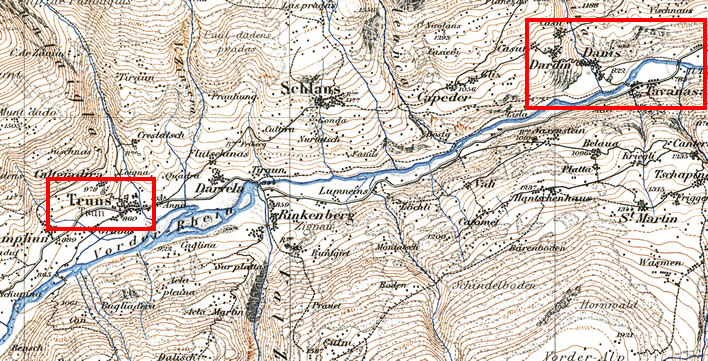

The route of the Swiss delegation to the meeting with the French general Demont and his troops in Tavanasa. The capitulation agreement was signed in Dardin. Image: Siegfriedkarte Swisstopo. [Click on an image to open a large version in a new tab.]

Demont had been born in France but his father had been a Bündner in the Swiss Guard. The capitulation was agreed, written and signed by both sides in the small village of Dardin on the evening of 9 March 1799. That should have been that.

Demont and his troops passed through Disentis without incident on 10 March. General Loison and his troops arrived on 15 March, but discipline was maintained and the anticipated revenge for the humiliation of his troops never occurred, despite Loison's reputation as a plunderer. He left with the body of his troops on the following day. The care of the French wounded undertaken by the monks of Disentis Abbey had impressed both commanders.

Unfortunately, despite this genteel beginning, the affair ended badly. Subjugation under the French jackboot was an unpleasant experience for people used to running their own affairs. Even those in the Swiss Republic in the rest of Switzerland were beginning to realise that they were now subjects of the French who were being systematically plundered in order to finance French military expansionism.

Masséna set up a puppet government and pushed through a forcible disarmament on pain of death. Persons who were held to have agitated against the French were rounded up, imprisoned and deported. When the main body of the troops withdrew, civilian-military administrators took their place with the task of extracting reparations and plundering the populace. France wanted money.

In Disentis the new Commissioner Bouernier demanded 100,000 Francs from the abbey, an unobtainable sum. When there was no cash left he took whatever valuables he could find. The abbey was let off the rest after paying a total of 80,000 Francs in cash and goods. Bouernier's successor in Disentis, Commissioner Hardeville set himself and his family up in some style in the abbey and persecuted the locals in whatever way he could.

'Looking east down the Rhine valley from Disentis, Switzerland', 1901. The left-hand image of a stereoscopic pair. Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

The fact that his wife was lodging in the abbey was a cause of outrage among the pious; that and her insolent manner and her flighty reputation – whether deserved or not – caused her to be hated as much as her husband.

Insurrection and revenge

Feelings rose and an uprising became inevitable – all strategic calculations were driven out of the insurgents' hot heads. The uprising began in the village of Tavetsch on 1 May 1799. Its timing seems to have been coordinated with an Austrian attempt to recapture the fortress on the Luziensteig.

Had that attack succeeded, the French in the lower valley would have found themselves in a desperate situation in between two enemies. But luck was on their side, the attack failed and they were free to continue their campaign in Graubünden. This situation continued until 14 May 1799, when General Hotze and the Austrians recaptured the fortress. Until then, the insurgents were left to face the enemy on their own.

In Tavetsch the five French occupiers posted there were taken bloodlessly and the insurgents proceeded to Disentis. In another sign of coordination, a horde of bloodthirsty locals from Medel met up with them in Disentis. The men from Medel would prove to be a particularly violent mob. The insurgents in Disentis had already overpowered a handful of French soldiers accompanying a flour transport. The soldiers were brutally clubbed to death. The commander of the French occupiers in the town was advised to surrender his soldiers in order to avoid unnecessary bloodletting. He refused, was taken out into a field and clubbed to death.

Various French positions in the town were overrun and their occupants killed. Those in outlying posts who managed to get away joined the main party of the French occupiers and took refuge in the abbey, thinking they could defend themselves there. However, a cook let the insurgents in through a back door and the French in the abbey were overwhelmed. Some of the French were taken prisoner, some clubbed to death on the spot. Eleven of them escaped and tried to flee through the forest, but they were hunted down by the locals until they collapsed. They were only spared from doom by the intervention of the local priest.

Once the insurgents had taken the abbey they set off on a hunt for Commissioner Hardeville and his assistant, the unfortunately named M. Fromage – the two people had persecuted them so much. Hardeville was found up the chimney of the same house in which the French Commander had been seized. He was smoked out (literally), taken to the abbey for confession, then taken out, tied to the wall of a nearby cowshed and shot. Fromage was also captured. He was fastened to the door of a cowshed, beaten and mistreated, then clubbed to death.

The garrisons in Brigels and Truns were also taken prisoner and taken to Tavanasa.

Once again, local democracy took over: on 1 May a citizens' assembly was held in Disentis, which decided to drive the French out of the country and march the militia on Chur.

The following day a group of insurgents from Tavetsch arrived in Disentis with their captives. There followed another bit of direct democracy, another assembly, to decide what to do with these prisoners. The insurgents wanted simply to kill their captives, but the assembly decided to keep them alive for the moment and put off the decision for later.

It became dangerous for anyone to oppose extreme violence, even priests and monks could be branded as traitors by advocating mercy to the French. In this fact there are ironic echoes of the situation often reported during the years of the revolutionary terror in France, when an advocate of mercy would often become the next victim. After the assembly, the militia set off for Chur with 81 French captives.

One or two of the militia took pity on the captives and attempted to release them. The others – in particular the bloodthirsty lot from Medel – were so enraged by this that they killed all the captives, bar two. One of these escapees had the misfortune to run into a party of weeders in Somvix, who took him prisoner and then stoned him to death.

One cause of the particular rage of the men of Medel against the French that led to many barbaric acts of revenge against helpless French captives was the wild sacking of Curaglia and other parts of the Medel valley during the initial French attack on Disentis on 7 March. Not only did the delay caused by plundering lead to the ultimate failure of the French assault, it left the local population lusting for revenge against the godless Jacobins. Everything the locals had been told about these devils had turned out to be true.

The rag-tag militia continued its march on Chur, joined by other insurgents from the villages they passed through. Nothing that wiser people said could divert this rabble from its suicidal intention to attack the French army in Chur.

The march on Chur

On the evening of 2 May the insurgent militia reached Tamins and Reichenau. They decided to put off the attack until the following day. The extensive wine cellars in Tamins and Reichenau had also fallen into their possession, with the result that a large number of the militia ended up blind drunk.

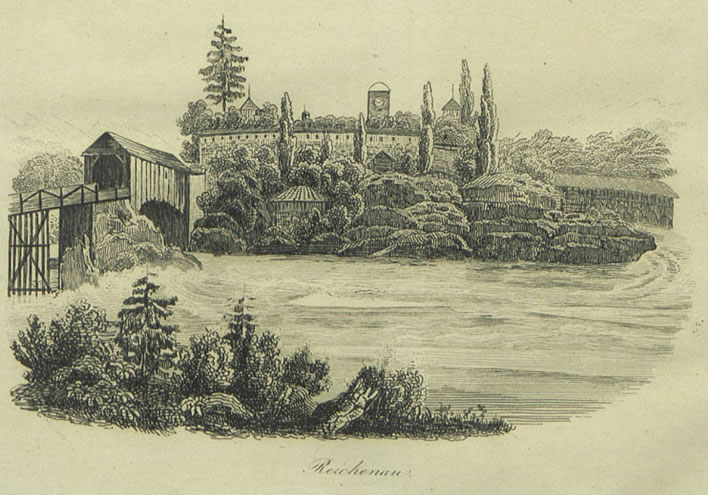

Reichenau, 1835. Vue sur l'Abbaye de Reichenau. Le lieu est protégé par des fortifications et est entouré par le Rhin. Un pont visible sur la gauche de la composition relie l'île à la terre. Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

The Swiss insurgents engaged the French on the plain between Tamins/Reichenau, Ems and Felsberg. Rifle fire and cavalry were particularly effective in this flat terrain. Image: Siegfriedkarte Swisstopo. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

An aerial photograph from September 1964 showing Ems (bottom), Felsberg (middle) and Chur (top). Image: E-Pics, ETH.

When the day of battle arrived they were scarcely able to stand up, let alone fight the French. 'Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we may die' – how true. Unsurprisingly, the French had become aware of the approach of the militia and had plenty of time to take up their positions. During the night, while the militia caroused, the French troops were getting ready.

An aerial photograph from 1946 showing Tamins/Reichenau (left, at the junction of the two arms of the Rhine), Ems (centre) and Felsberg (right). The Kunkels Pass can be seen coming in at top left. This area was the battleground where the insurgents met their fate – flat, open countryside, perfect for cavalry, artillery and riflemen; not so good for clubs and axes. Image: E-Pics, ETH. [Click on the image to open a large version in a new tab.]

The militiamen who attacked the French positions may have been half-drunk and out of control, but the ferocity of their attack was remarkable. It was so fierce in fact that at two positions the French were forced to fall back and regroup. But artillery, cavalry charges and reinforcements from the Luziensteig brought the militia mob to a standstill, then the standstill turned into a rout. A French company cut off their retreat and the mob was slaughtered. The militia lost 638 dead on that battlefield. Those who could, attempted to flee back up the valley but were pursued by the French, who plundered and burned down the villages along the route.

The French revenge

On 5 May 220 years ago the French and their commander General Philippe Romain Ménard (1750-1810) arrived in Disentis, bringing us to the anniversary we are commemorating today. The village was immediately plundered. That evening the French discovered the blood-covered uniforms of the French prisoners who had been clubbed to death. They had been stashed in the abbey. In a rage they turned on the villagers, 22 of whom were killed.

The discovery of the bloody uniforms and the traces of blood that could still be seen on the roads in Disentis were just the last push the French needed to descend into barbarism. The mood among the French troops had been prepared before they even set off by the gory tales told to them by Hardeville's widow, who had taken refuge with her young son in Ilanz. The uniforms and the bloodstains were the confirmation of her horror stories.

The following day the French made to withdraw from Disentis. Before they left, however, they set fire to the abbey and several parts of the village. On that day Disentis lost its abbey, its abbey church, its library and its archives in the conflagration; in the village 110 houses and 102 cowsheds and barns were burned down.

The French surrounded the village during this action and when the villagers tried to flee the flames they were killed or driven back into the fire. 20 people died in this way.

Severe reparations were demanded from every village in the Cadi, meaning that the French took the livestock and produce of the farms, leaving the populace impoverished, a population of many widows and orphans. There was no more hotheaded talk of uprising after that.

There didn't need to be. On 14 May the Luziensteig had been recaptured by the Austrians. The following day the French abandoned Chur and Reichenau and made their way up the valley back to Disentis and then over the passes back into Italy. The region proved to be as difficult to hold for them as it had been for the Austrians. The terrain is only just capable of supporting its inhabitants – supporting a standing army of sufficient size was out of the question.

The French had taken what they could and now they left for other fields of combat. On the way they burned and pillaged and destroyed most of the bridges over the Rhine and tributaries. The whole gruesome action had destroyed Graubünden within the space of two and a half months.

Conclusion

Once the French had brought the Drei Bünde to its senses, the Swiss Republic involved itself. The then puppet government of the Republic, the Swiss Directory in Aarau, had already on 13 April 1799 sent two of its commissioners, Johann Herzog (1773-1840) and Joseph Schwaller (dates unknown), to Chur to effect the integration of Graubünden with the Republic, a task which they fulfilled, at least nominally, by 21 April, the date on which Graubünden ceased to exist as a political entity.

After the sacking of Disentis, the French spread the rumour that the monks of the abbey had been, in fact, the brains brains behind the knuckle-dragging, enraged peasantry. The Jacobins of the French Revolution had no sympathy for the Catholic church, which they thought, not unreasonably, had for centuries been the docile handmaid of aristocratic interests.

The monks were certainly no friends of the secular French Revolution – how could they be anything else? – and would have certainly felt a natural affinity for the profoundly Catholic Austrian Empire. Was it just a coincidence that the core of resistence to the French had been based in the territory of Disentis Abbey?

The Swiss Directory listened to the French rumours and issued an order to its two Commissioners in Chur to abolish the abbey and bring its monks to stand trial in Zurich. What the French had started, their Swiss puppets would bring to fulfilment.

Amongst all the irrational hate and bloodthirsty revenge of our tale so far we have at last found two heroes: Herzog and Schwaller, the two Commissioners now running Graubünden. In Chur they were completely aware of the feelings of the devout local populace and chose to do nothing to implement the instruction from Zurich.

In ignoring that order they declined to give another turn to the screw of blood feud and revenge that had wreaked such destruction and loss of life. Although still under the yoke of the French/Swiss oppressor, Graubünden now had at least a small chance of a future. Those who seek the hand of God in historical events should consider the miracle of the appointment of Johann Herzog as a Commissioner for Graubünden, since he had already during the years of French encroachment, 1798-99, opposed the French 'leeches'. He would remain stoutly independent in the best Swiss manner for his entire political career.

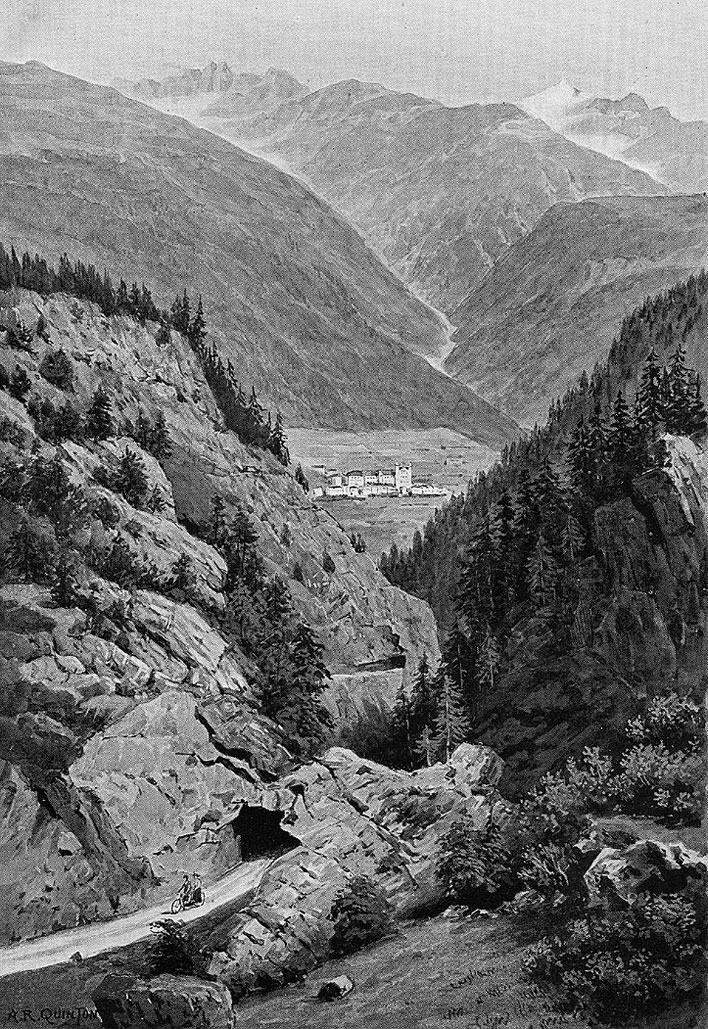

'A view near Disentis' in Cycling in the Alps with some Notes on the Chief Passes, 1900. Image: ©Bibliothèque cantonale et universitaire de Lausanne (VIATICALPES).

The further bitter irony is that, once the Swiss Republic had been plundered, in 1803, scarcely five years after it had been set up and four years after the Drei Bünde had been crushed, Napoléon lost interest in that project, having now bigger roles to play on the European stage. Those four years, that imperial whim, had cost the people of the valley of the Vorderrhein dear. The villages took generations to recover; the loss to Romansh culture in the destruction of the library and archives of the abbey of Disentis is difficult to measure, since the significance of the losses was without doubt inflated for propaganda purposes. But a lesson had been learned: local autonomy was good, regional power was better.

A photograph of the modern Disentis Abbey. The building destroyed on 5 May 1799 was rebuilt. The replacement itself burned down without French help in 1846. The replacement for that has been restored into oblivion in the intervening years, leaving us with today's monstrosity. Image: Benediktinerkloster Disentis

Even today, 220 years after this sad episode, the Swiss Confederation is still trying to come to terms with being an albeit sort of independent minnow in a pond of pike. Nowadays, just as in 1799, some Swiss want sturdy independence at whatever cost, some Swiss want subjugation at whatever cost and some just want the whole thing to go away, also at whatever cost. As the people of Graubünden found, it won't.

Literature

This account has plundered many sources. The principal ones are:

- Condrau, Placie. 'L'ujarra della Surselva encunter ils Franzos' in Calender Romontsch 1899 p. 81-109.

- Decurtins, Caspar. 'Der Krieg des Bündner Oberlandes gegen die Franzosen' in Feuille centrale, Organe official de la Société de Zofingue, Quinzième année, nr. 2 Décembre 1874, p. 69-191.

- —, tr. Pieder Antoni Vincenz, 'L'ujarra della Surselva encunter ils Franzos' in Ischi, 3, 1899, p. 97-146. [This is ostensibly a translation of the previous work into Romontsch, but contains additional material.]

- Placidus a Spescha. 'Die Ereignisse im Bündner Oberland im Herbst 1798 bis zum Brande von Disentis 6. Mai 1799' in Sein Leben und seine Schriften Pieth/Hagar, 1913 p 74-127.

- The Archiv Communal Tujetsch maintains a website containing an extensive range of materials on many aspects of the history of the region.

Update 08.05.2019

Added several illustrations.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!