Mr Cherry

Richard Law, UTC 2020-03-08 10:12

A recent James Higham flashback …

One learnt that it was best not to mention anything medical to mother because it would either end up worse with this horror liquid [Mercurochrome] on it or else she'd take you to the GP if it was bad and that was always injection time – GPs are fiends.

… triggered one of my own.

Once summoned, many ghosts attended. The one we shall confront today is Mr Cherry, the barber.

His shop was just across the road from our house, so there was no opportunity to dawdle. I did not go gently to Mr Cherry's, though: having my hair cut was a torture. Only the threat of a worse torture from my Mum and the promise of kept change would get me to scuff my feet the fifty yards to Mr Cherry's, clutching, what would it be – a shilling? Thinking back, it is astonishing that Mr Cherry would expend so much effort for such a small coin. It was, however, a big coin at that time.

Inside the torture chamber, a solitary chair faced the small mirror on the lefthand wall. It was a completely ordinary bare wooden chair with arms. Certainly it had none of the adjustment mechanisms we expect today. Three or four wooden chairs without arms backed onto the righthand wall.

Along the wall opposite the door were two aquaria. One contained a couple of angel fish which hovered pensively or occasionally made stately glides up and down the tank. In the other one, various small stripy things dashed about aimlessly – but obviously with no time to lose. Tropical fish were Mr Cherry's commercial sideline.

There was brown lino on the floor, dim green and beige walls, and brown paintwork.

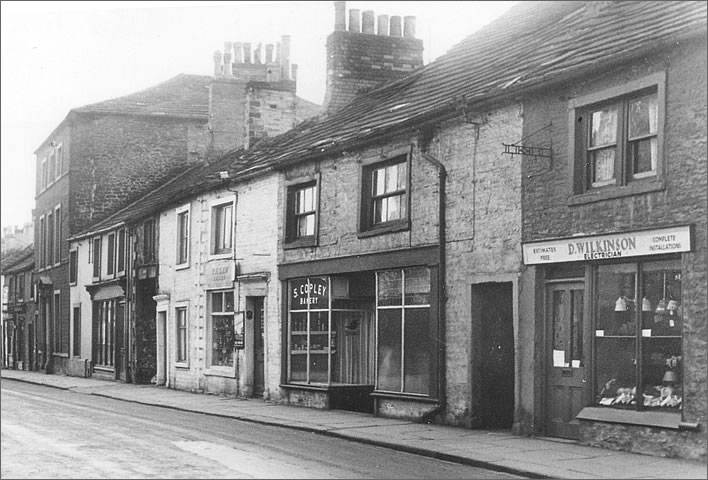

Mr Cherry's shop, awaiting its doom. The nearby properties were demolished in 1957; Mr Cherry's building was left to linger under sentence of death until finally felled in 1966. Image: The Rowley Collection.

There wasn't a lot to take my mind off my fate whilst waiting for my turn: last month's Dalesman and an assortment of pages from the previous day's Telegraph and Argus. There was a local cricket club calendar on the wall.

Perhaps I'm oversensitive, but faced with my own impending doom I didn't find watching Mr Cherry's fishy prisoners zig-zagging mindlessly around his tanks waiting for their time to come particularly entertaining.

Eventually my own time would come and Mr Cherry would set about me. The experience was nasty, brutish and short. In that long-gone age, in which there was little hope of alleviation for most of the painful experiences that befell us, the motto was: 'get it over with'.

The one compensation was that Mr Cherry was a compulsive conversationalist, even with an eight-year-old. In the course of removing the odd mole from the back of your neck, he could range from weather to livestock prices and was indeed remarkably knowledgable about things like sherbet lemons, balsa-wood aircraft and where to catch the best crayfish.

He had that great skill of the true conversationalist – he led you to believe that this conversation was completely unique and interesting to him, whether you were an eight-year-old lad or an eighty-year-old farmer. In reality he had probably reprised most of these topics several times that day or week. Like his fish visiting every corner of their aquaria again and again, it all must have seemed somehow new with every customer.

That said, my impression (right or wrong) is that at that time adults usually spoke to children in adult ways and expected us to become adults in order to understand them. We were, after all, the ones who had to learn about the world.

Perhaps this is just a phenomenon of dialect speech: there isn't a 'high tongue' in a dialect – the forms of expression are the same for everyone and abstractions are generally shunned. In comparison with today's habit of infantilisation of anyone under thirty, the children of the fifties became men and women quite quickly. Good judgement may have taken its time to grow, but understanding came quickly.

From these times in the chair and all this discourse, one phrase in particular is burned into that eight year-old's memory: 'styptic pencil.' This was the magic phrase that had summoned up these spirits. A couple of these objects, looking rather like sticks of chalk, were on hand next to the basin. They were all you could see while Mr Cherry pressed your head forwards as he mowed up and down the back of your head and around and over your ears.

In those days before Kleenex the inevitable nicked mole or ear would get a dab from a styptic pencil and the eight year-old would comprehend only too well the other big words on the label: 'astringent properties.' They had bloody ends, of course, from a hundred earlier customers. That fact alone would today lead to road blocks, circling helicopters and a team in hazmat suits.

The prisoner finally released and the barber paid, the change would go on the astringent properties of a bag of sherbet lemons. That's that over with for another couple of months.

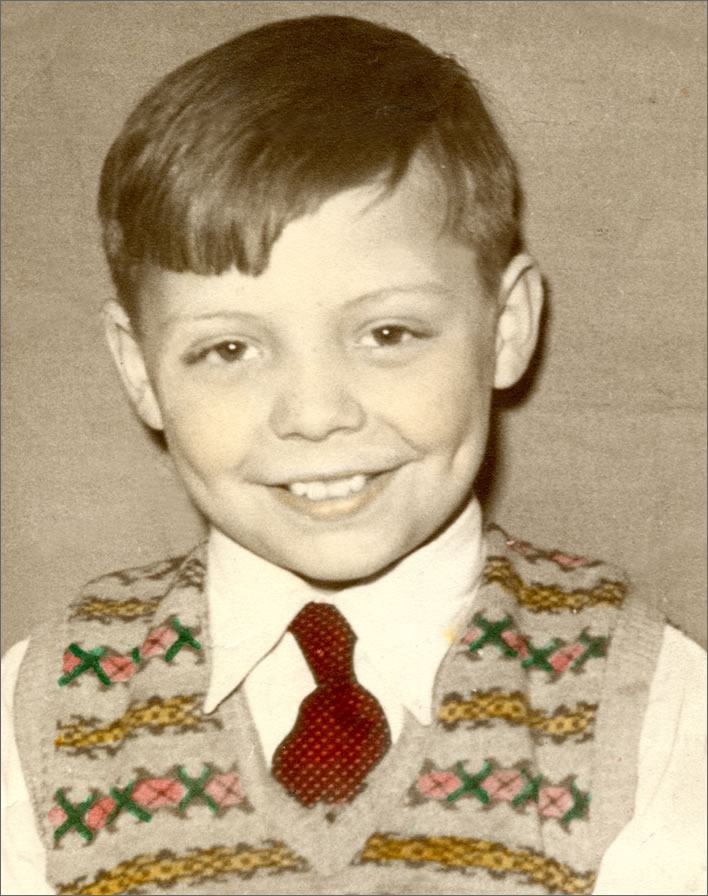

The seven-year-old chick magnet himself. Those Cupid's bow lips! That winning smile! Those dimples! That haircut! (Mr Cherry's Führerbunker style) – this boy will break hearts! But where did it all go wrong? Image: ©Figures of Speech.

Thinking about it, those days were before anything, not just Kleenex – calculators, deodorants, pine kitchen units, I could give you a long list. We had almost nothing apart from the utilitarian clothes we wore.

What did we have? A lot of brown paint, mainly – but also a freedom that now seems stupendous. I wandered and later cycled far and wide and was almost never asked where I had been or where I was going: 'out' was quite sufficient. Don't ask, don't tell. Every right-thinking adult knew where 'out' was – a place where only children could go.

L.P. Hartley's (1895-1972) now proverbial opening sentence of his 1953 book The Go-Between expresses a deep insight: 'The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.' Writing in 2020 of those times in the 1950s when Hartley was writing, we should write now not of a foreign country but rather of a different planet, so great have been the changes in those seventy years.

The changes to British life in the thirty years between 1950 and 1980 were enormous: a step change resulting from a substantial increase in affluence combined with major developments in technology and the media. Everything changed: housing, roads, cars, radio, television and consumer products. For this reason it will be very difficult for most people born after 1970 and therefore now under fifty to comprehend fully the conditions of life in the 1950s.

There was a cluster of shops close to Mr Cherry's shop – butcher, baker, grocer, newsagent. Shopping was done frequently in small quantities that fitted into a cane shopping-basket. Hardly anyone had a refrigerator, just cool pantries, meaning that foodstuffs had to be bought in quantities that would keep and were affordable for a weekly wage – that small brown paper envelope with a note or two and some coins in it.

No one knew anything of supermarkets, shopping trolleys or habits such as 'the week's shop'. There was no 'self-service' – whatever you wanted you had to ask for. There were no sell-by dates, meaning that the shopkeeper gained and kept his customers by trust and fair prices. The food industry was yet to develop foods that could be bought in large packs and kept for long periods.

There was even an electrician, profiting from the electrification of the houses of the working classes. He sold light bulbs and the grocer still sold gas mantles.

Whilst it is difficult for today's generations to comprehend the life of the 1950s, it was relatively easy for adults in the 1950s to comprehend the conditions of life fifty or even seventy years before. My parents were born in the early 1900s, making them Edwardians by birth. Their lives and their living conditions hardly differed from those of their parents. The parents of the children of the 1970s were mostly postwar children, thus Elizabethans by birth.

During that great step change, the Grim Reaper's scythe swung through these Edwardians, who had survived two world wars and a great depression, unemployment and grinding near-poverty, just as the planners' wrecking ball swung through their houses and shops.

After a few years of planning blight, the shops and houses around Mr Cherry's shop were demolished in 1957. His shop stood for a few more years, finally meeting its end in 1966.

Top: The cluster of shops opposite Mr Cherry's barber's, photographed sometime between 1953 and 1957.

Bottom: A photograph taken during their demolition in 1957. Images: The Rowley Collection.

I never heard my parents use their Christian names – certainly not in public, when they unfailingly addressed each other as Mr and Mrs. Even if they had had a car, it would not have been used for transporting me around. For a brief moment in the late 1950s they had a telephone, and in that were distinguished from the great mass of their contemporaries.

We children had no limits placed on our speech – we could say exactly what was in our minds as long as we avoided bad language and were sensibly discreet in what we told our parents. Avoiding bad language was easy, because nobody used it in everyday life. Discretion, though, sometimes required effort and skill. After one particularly grandiose fairy tale my mother gazed steadily into my eyes and murmured: 'Remember, a mother always knows'. She did, too, without needing to ask.

I went unaccompanied to Mr Cherry's – I did almost everything unaccompanied in those days – walked up the hill to primary school, walked to my friend's house, walked through the woods and over the moors. During the school holidays, my life was largely lived outside the house.

The primary school was on the outskirts of the town, about half a mile away from our house. The route there led up along a walled lane canopied with trees. The school was known as 'The Huts' and consisted of two, single-story, brick structures. It was a rudimentary makeshift to cope with the peaks of the postwar boomer generation. Only a few years before, I believe, it had been used as a rudimentary makeshift to accommodate prisoners of war.

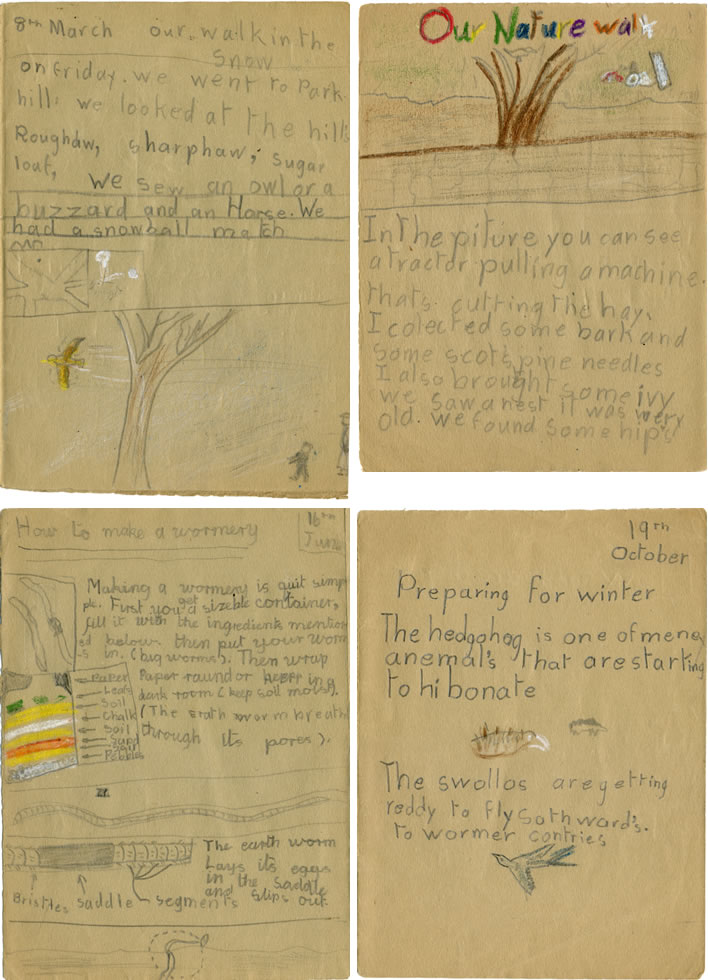

I might make a joke here about the parallels between prison camp and school or the dominant role of the makeshift in my education, but in fact all my memories of that school are happy – very happy, in fact: learning to read and write I found satisfying; learning the arcane carry techniques of arithmetic perhaps less so; there were nature walks in every season and writing entries about them in our nature diaries; we listened to the BBC's radio broadcasts for schools and wrote about them; we tended the school's garden and wrote about that, too.

Once we had learned to write, the skill was not allowed to fall into disuse. Here are some pages of the seven-year-old diarist from 1954:

The youngster could not realise how he would come to miss those times – miss even his chatty tormentor and his damned styptic pencils.

But all these things – bad and good – have gone over the waterfall. Mr Cherry is certainly dead and gone, along with all those teachers who did their best for me. My parents, too, long gone. All gone irretrievably over Time's waterfall.

However hard we try to banish these ghosts they choose to reappear from time to time unforeseen: a word or two – 'styptic pencil' – is enough to summon them. They remind us of that impossibly distant country and the nostalgia, correctly 'homesickness', which most of us carry within us.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!