Paying the Harvesters

Richard Law, UTC 2020-08-01 03:05

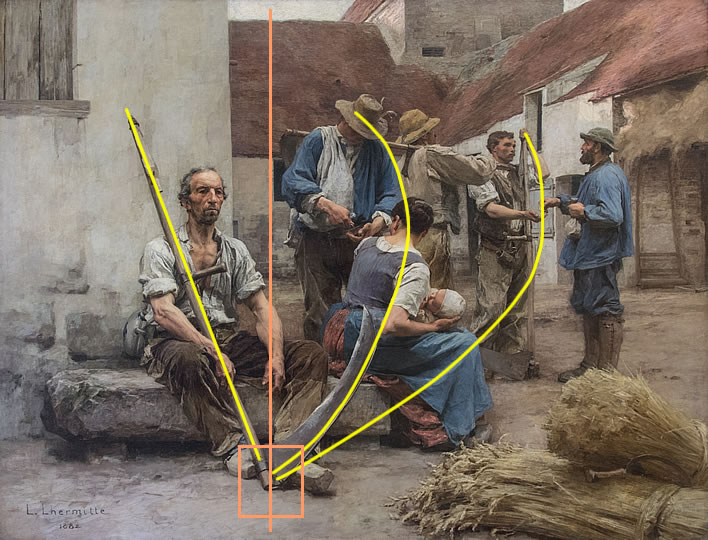

Léon Augustin Lhermitte, La Paye des moissonneurs / Paying the Harvesters, 1882. Image: Musée d'Orsay. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Léon Augustin Lhermitte (1844-1925) was born in Mont-Saint-Père, a small town in the Aisne Département in north-eastern France. Despite his education and career success in Paris, his heart remained in rural France, particularly with the agricultural labouring classes. He admired the work of Jean-François Millet (1814-1875), a specialist in the depiction of the rural poor from the previous generation.

One of his nicknames was le peintre des moissonneurs, the 'painter of harvesters', and it was his 1882 painting, La Paie des moissonneurs, 'Paying the Harvesters', which was his great career breakthrough. The painting was esteemed both by the general public and by his artistic peers.

Our look at the painting in this article is not an exhaustive study intended for art specialists. It is mainly an attempt to answer the question that most people would ask themselves on looking at the painting: why is this painting so attractive?

Context

The situation depicted is of what appears to be a family of harvesters, at the end of their day's work, receiving their pay. To risk being pretentious for the moment – a speciality of this website! – we are at the interface between the class of propertied farmers and rural day-labourers. This division between settled property owner and transient or journeyman labourer has existed for a long time as a result of the symbiotic relationship between the two.

The relationship is not as exploitative as it may first seem, since when the crop is ripe in the field or hanging full on the vine, owners need their labourers just as desperately as the labourers need the owners.

It is interesting to see how far we have come with Lhermitte's realism of 1882 from Léopold Robert's acclaimed treatment of a similar subject from just over fifty years previously. We looked at it on this website a couple of years ago:

Léopold Robert (1794-1835), L'Arrivée des Moissonneurs dans les marais Pontins, 'The arrival of the reapers in the Pontine Marshes', 1830. ©Musée du Louvre, Paris. Online.

The exotic, colourful and erotic romance of Robert's painting, with no sense of economic or social reality at all, has given way in those fifty years to Lhermitte's gritty, undecorated realism. The social, economic and cultural revolutions in France make Robert's work seem to come from a different planet – we might paraphrase: fifty years of awakening.

Imagery

Let us consider first the imagery in Lhermitte's painting.

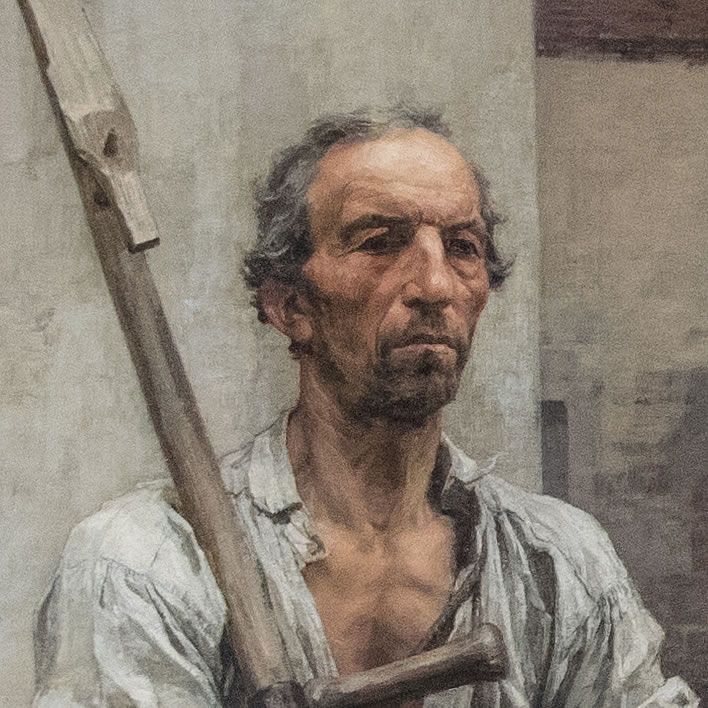

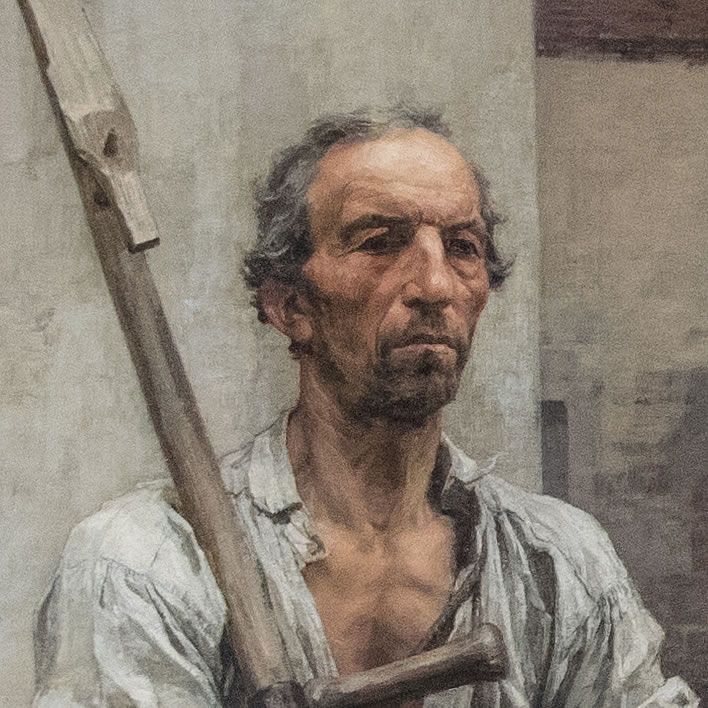

The observer's eye almost certainly settles first on the figure of the seated harvester on the left of the composition – how could it not be arrested by this remarkable figure?

It is an almost photorealistic depiction of an older man who has just completed hours of labour scything corn. He is sitting on a stone bench. We must assume that he is weary from his day of strenuous physical work, but we do not see this in his posture: he sits erect, not slumped, the shaft of his scythe is not being used as a support. His head is held straight, not bowed, the gaze looking downwards, distantly unfocussed. The masterful representation of the arms and hands is a clear indication of his weariness, but the posture is so controlled that it is almost balletic.

The figure and face of the hired harvester is an expression of something – but of what? Similar facial expressions can be found among depictions of exhausted labourers in other works by Lhermitte as well as in Millet, Bastien-Lepage (1848-1884) and van Gogh: essentially an unfocused, downwards stare. Moderns might say 'wiped out' or 'spaced out':

Léon Augustin Lhermitte, A Peasant Woman Resting, 1903. Image: Cincinnati Art Museum. [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Jules Bastien Lepage, Hay Making, 1877 (detail). Image: Musée d'Orsay.

Readers can play this game on their own – some will find exhaustion in the harvester's face, perhaps also nobility; there may be dignity, acceptance, resignation, hopelessness or worry. The one thing we don't see is any hint of satisfaction for a good job well done. That is not an emotion which rootless day labourers know.

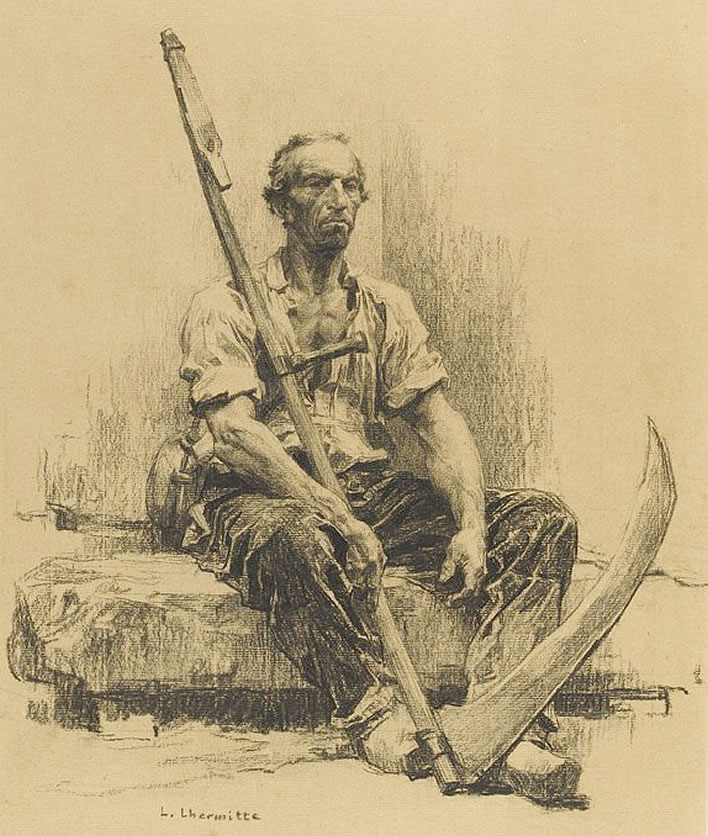

As we have already noted, the figure of the harvester is the image that the observer sees first. It may be off-centre in the composition, but it is indisputably the most dominant image. Lhermitte treated it with appropriate care: we have a sketch showing a very detailed study done by him for the painting:

Moissonneur assis, se reposant (Signé, en bas, à gauche : 'L. Lhermitte'. Etude pour 'La Paye des moissonneurs'). Image: Musée du Louvre département des Arts graphiques, ©RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) - Thierry Le Mage.

Whilst the other figures in the composition are engaged in payment transactions, the old harvester sits aside from that process; his exhaustion embodies the backbreaking work in the hot fields which the harvesters have performed for the coins that they are being paid.

Remarkably in this composition of seven people (including baby) only two other faces are shown distinctly. These belong to the young man with his hand out receiving his silver coin and the bearded farmer giving him his pay. Neither is looking at the coin as it is being handed over, but both are meeting each other's gaze directly.

This pose is unusual: we would expect the two to be paying attention to the money being handed over – just as the farmer and the woman are doing in their transaction elsewhere.

With these expressions Lhermitte is showing us a social interaction, but once more, as in the case of the seated harvester, ambiguity allows much room for individual interpretation.

What is the nature of the expression in the young harvester's face? It appears to be proud, perhaps resentful, certainly not showing deference or humble gratitude: no forelocks are being tugged here; the pronounced eye contact even suggests some sort of mutual challenge. The young harvester's posture is unbowed, indeed, noticeably upright – we have the shaft of his scythe as a guide – as is the posture of the other harvester standing next to him. Is this a symbol of the tension between capital and labour? Is this nobility or resentment?

The young harvester is being given a single silver coin. Nothing hints at the existence of more coins already in his hand, but we note that the plump money bag is being held firmly shut – no more coins are coming out of that. Is this a hint by Lhermitte of the divide between the day labourer's coin in the hand and the property owner's swollen purse?

Another transaction is taking place in the centre of the composition: a farmer is counting a silver coin into his hand whilst the woman watches. This pose is dramatically unlike that of the young harvester's proud, challenging demeanour during his payment: the woman is occupied at the moment suckling her baby and her full attention is focused on the hand counting out the money. There is no direct eye contact – in fact, we cannot see the eyes of either of them.

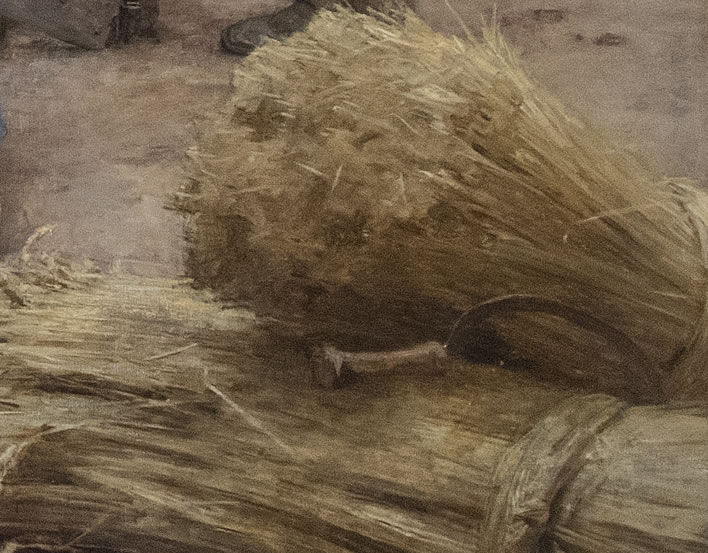

The male harvesters have their scythes with them. Between the sheaves at the front of the composition is a sickle, which must belong to the woman. Whilst the men hang on to the tools of their trade, the woman has put hers, the sickle, aside in order to feed her baby.

Female reapers with sickles depicted in Léon Augustin Lhermitte, La Moisson, 1874 (detail). Image: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Carcassonne.

The sickle in Lhermitte's painting A Peasant Woman Resting (shown above).

The day labourer's economic unit has no room for the unoccupied: just as the men, she too has spent the day working, her main job being to gather, trim and bind the corn into sheaves. The sickle will usually be used to cut tufts of corn missed by the broad swathes of the reapers' scythes.

Differential detail

Whilst we have these various sections of the image before our eyes let us just briefly consider Lhermitte's mastery of differential detail.

In a photograph, the skilled photographer can determine the centre of interest of the composition not just through aim and focus but also by choosing an appropriate depth of field using aperture and exposure time. The centre of interest is brought into sharp detail and less important features are softened and blurred.

Skilled painters do something similar by varying the level of detail within their paintings: the centre of interest is given a high level of detailing, whereas backgrounds and secondary elements are given little detail in order to prevent them becoming distractions. This technique has been in the painter's toolbox for centuries: the trick is to use it without anyone noticing.

We have Robert's L'Arrivée des Moissonneurs to hand as an example of a competent but unexciting use of differential detail. In it there are essentially four layers of detailing: some foreground detail; then the uniform, high level of detail of nearly all of the main narrative elements; a few slightly faded figures behind them; then the final level of background landscape fading into the distance. The level of detail is essentially determined by perspective distance – all the important figures are in the foreground plane anyway.

In effect, Robert's extremely complex central group – humans, oxen and waggon – with all its many sub-narratives, is presented as a single block, the component parts of which the observer must then disentangle with no further help from the painter. We might say that Robert's painting doesn't have a central narrative, just a collection of exotic cameos.

In comparison, Lhermitte's handling of differential detail in La Paye des moissonneurs is masterly. Peak detail is achieved, of course, in the figure of the seated harvester (and particularly the face). But readers are invited to look at the extraordinarily skilful way in which Lhermitte changes the level of detail of the various elements of the composition to accord with the significance of each element in the general narrative of the painting. Everywhere there are foregrounds and backgrounds.

Consider, for example, in the two transactions the bright detail of the coins and the veined hands holding them, then compare this with the softer rendering of the figures around them. Lhermitte is telling us: 'follow the money!'

The detailed rendering of the mother and child, for example, even though we cannot see her face, should be compared with the much rougher rendering of the figure of the farmer paying her, whose clothes are rendered vaguely and whose face is the merest shadowy gesture.

The mother's gaze is fixed on the coin, which, the centrepiece of the action, glistens at us brightly, as well as the counting hands of the farmer, also rendered with great detail. Compare the careful detail of her shirt and dress with the much rougher working of the farmer's clothing and the even rougher rendering of the harvester standing behind him.

As a final example let us look at something which Robert could not bring himself to do: violate the softening of perspective distance. The sheaves and the sickle may be in the foreground, but Lhermitte has nevertheless painted them as mere suggestions, not detailed in any way that would distract (given their very dominant location) from the more important elements of the composition.

Whereas Robert rendered his foreground in detail because of its proximity to the point of view in accordance with the laws of optics and of conventional painting, Lhermitte had the courage to render his foreground as vaguely as others might render a background.

Structure

Each of the component images in the painting is imposing in itself. Lhermitte is generous in his imagery: three or four of these elements could have made respectable pictures in their own right. However, the pleasure of looking at this painting does not just come from the superbly realised detail, but from the structure of the painting as a whole.

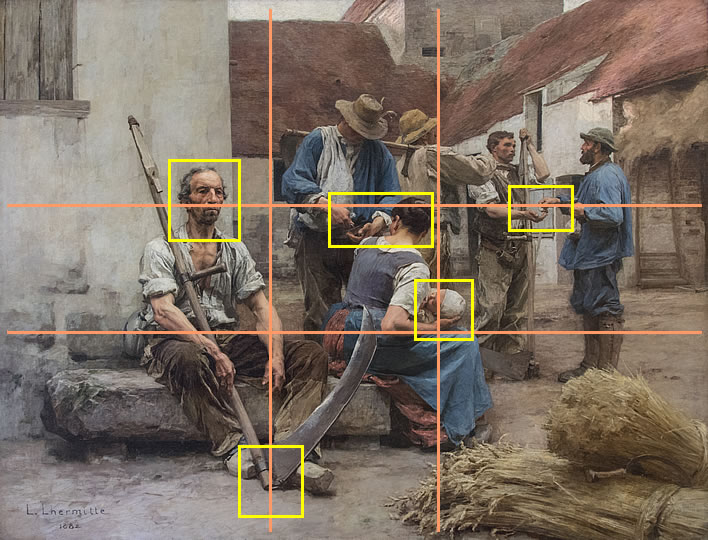

Golden Ratios

Let us see firstly how the composition of the painting uses the Golden Ratios ('GR', 1:1.62) that have been so valued by artists down the ages.

There are four possible GRs, depending on which of the four edges of the painting we measure from. It is easy to see from the diagram that each of the most important narrative components of the painting is located on a GR:

- the harvester's head, the payment to the woman and the payment to the young man are all positioned on a horizontal GR;

- the suckling baby is at the intersection of a horizontal and a vertical GR;

- the head of the harvester's scythe lies with utter precision on a vertical GR.

This positioning is clearly no accident – any painter would be delighted to be able to construct such a design.

We can also appreciate another reason why the figure of the seated harvester has such a dominant role in the composition: the harvester's head is located exactly on one horizontal GR; the centreline along his waist on another horizontal GR; his feet, supporting the head of the scythe are located on the important vertical GR.

The economic trajectory

The upper GR line is of great importance in this painting. We noted earlier the expression of youthful pride in the face and posture of the young harverster on the right of the picture, who is just being given his pay.

This point is at one end of an economic trajectory which follows the upper horizontal GR line from right to left, taking us across scenes of the economic milestones from youth to age.

We start with the posture of proud youth, almost defiantly accepting his pay, not even deigning to look at the coin; next we encounter the posture of the concerned mother with a child to feed, intent on the money, indifferent to the payer, who is a dominant male figure towering physically and economically not only above her but above all the other figures in the composition; finally we arrive at the apathetic face of the ageing harvester, worn out, who has experienced this same scene through many seasons. For him, nothing has ever changed.

He knows all about the pennies that change hands. If the young harvester still has some hope or pride, the old harvester has none. His situation is no longer about a single payment.

Lhermitte was a painter of the rural poor in the region in which he was born and grew up. He needed no extended sociological analysis to understand the life situation of the people he painted. The seated harvester is trapped in an inexorable physical and economic decline. A human body can only do this kind of labour for so long; ahead of him he faces the non-future of the short life expectancy of the members of the mal- and undernourished rural labouring class. He was never able to earn enough to escape this path.

He is an ageing man. He has no pension, no savings, no property. He sells his labour for money; when he can no longer work there will be no money. He will either die quickly, in which case the issue has been solved, or linger on, dependent on those who can barely afford to keep themselves alive or some hard charity. He may as well let the youngsters look after these pennies.

Should the reader doubt the existence of this trajectory, he or she should reflect that the significance of its three points is not only established by the GR on which they are all located but also by the level of detail with which they have been rendered: each of them is an important element which has been rendered with precision and which has been lined up in a significant way.

Of course, we can trace this trajectory in either direction: left to right from the old man to the young man he once was or right to left from the young man to the old man he will become.

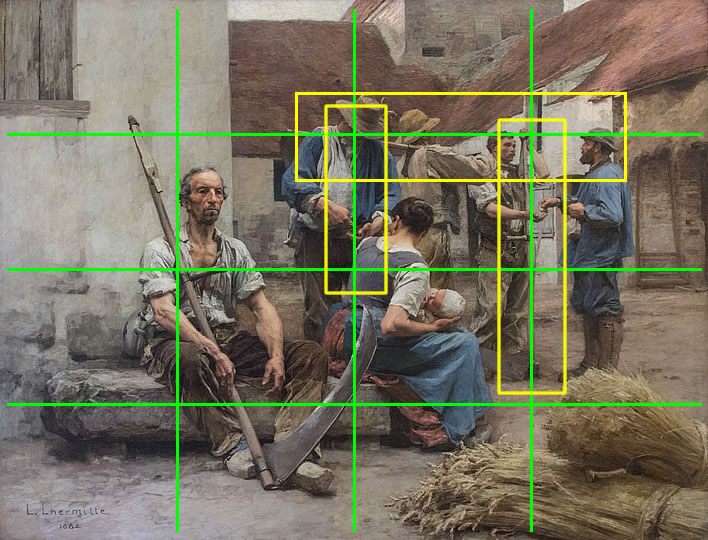

Fractions (quarters)

If we divide up the painting into simple quarters, we note that:

- the top quarter line binds the four male heads in the group of farmers and harvesters;

- the scythe held vertically by the young harvester receiving his pay falls exactly on the division between the third and fourth quarters horizontally;

- the vertical line from the head of the farmer paying the woman and his hands counting out the money lies on the exact vertical centreline of the composition.

The second and third of these groups, placed in such important locations, form the narrative that corresponds with the title of the painting: 'Paying the Harvesters'.

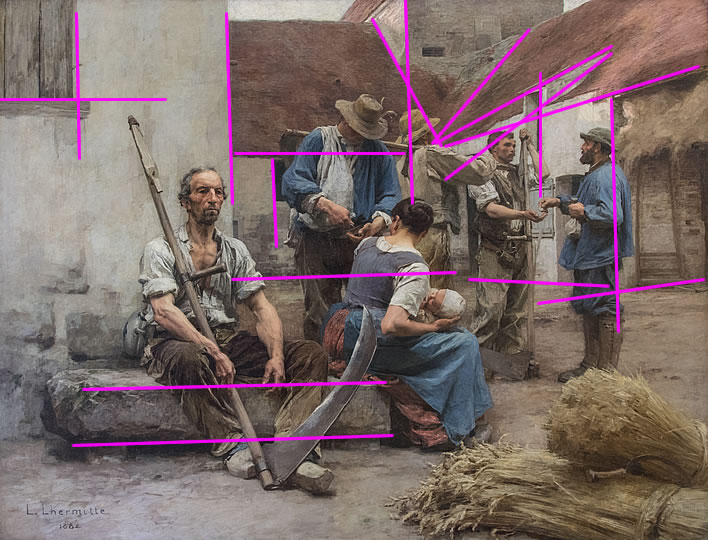

Alignments

If, instead of the right-angled structures over the field of the full painting, we draw the alignments between objects within the composition we find numerous relationships which serve to bind individual elements of the composition together.

Firstly, the lines created by the buildings of the farmyard, particularly the roof edges, direct the observer's attention subconsciously into the centre field of the composition. In the centre of this, in turn, is the payment being given to the woman, which we found to be located exactly in the horizontal geometric centre of the composition.

On the right, the line that runs down the vertical edge of the window in the barn terminates exactly on the coin that is being handed to the young harvester.

Secondly, within the collection of figures there are important alignments which represent the many dynamic interrelationships which create the narrative of the painting: the heads of the group of men are aligned in a descending path; the payment action binds the farmer at the right of the composition to the young harvester and thus into the main group.

The most important group consists of the figures of the farmer near the middle of the composition, the mother and her suckling baby. There are several alignments in this crucial section of the painting.

An important alignment is created by the woman watching the paying farmer's hands attentively; a further line goes from the paying hands, across the mother's shoulders to the head of the suckling baby; the heads of the payer, the mother and the baby rest on another line.

The desperate importance of that payment for the mother and her baby is thus made manifest in these alignments. It is, ultimately, the money which feeds the baby.

A further alignment arises from the edge of the stone bench on which both the elderly harvester and the woman are sitting. This is the alignment which joins the figure of the seated harvester with the figure of the woman, binding him into the main group in the centre of the composition.

Thirdly, in addition to linear alignments the painting contains several subconsciously satisfying geometrical shapes.

These shapes are not simply random figures that could be found in any composition – a moment's reflection will reveal their significance for the narrative of the painting as a whole.

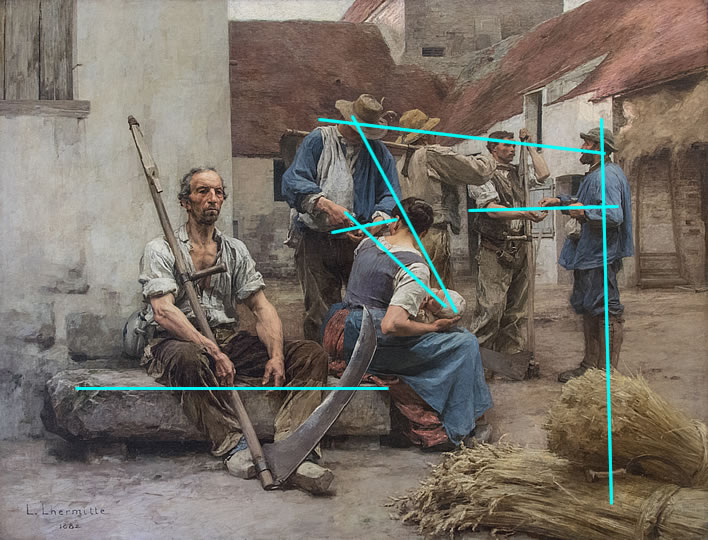

Scythes

At first glance we might think that the figure of the seated harvester, although itself very striking and including two important GRs, is not particularly tightly bound with the busy figures of the central group.

That is true only insofar as we consider straight-line alignments, since the only connection we have established so far is the line of the edge of the stone bench on which the harvester and the woman are both sitting. But the figure is connected with the group in other, more subtle ways.

We noted that the head of the scythe held by the seated harvester is positioned exactly at a key GR.

From this point, curved, scythe-like alignments run into the central group. These lines are not simply imaginary: they follow the edges of the objects in the group:

- a line formed by shaft of the scythe binds the figure of the seated harvester to the crux of the GR;

- from thence a line follows the curve of the blade of the scythe, then runs along the edge of the woman's arm that is holding the suckling baby, then up her neck, over her head, along the outer edge of the arm of the farmer, to end at the middle of his hat;

- a second, less well-defined scythe-like line runs from the head of the scythe at the GR, along the folds of the mother's skirt, along the folds in the young harvester's trousers, over the hands of the payment, then along the young harvester's arm to end at the point where his hand holds the top of his scythe.

Professional harvesters might find the blade of the scythe a little on the big side, which, if true, only goes to demonstrate the compositional importance of the blade in establishing these alignments. The head of the blade is located on a horizontal GR, its tip on another. Lhermitte seems to have wanted to make sure that this alignment was clearly established for the observer.

We now understand the quite brilliant way in which Lhermitte has led the observer's gaze from the seated harvester, who forms the entry point into the painting, via the important GR at the head of the scythe into the other important components of the composition.

There is another alignment in the picture which is created by the scythes held or carried by the two younger harvesters in the group. As we have seen, the vertical line of the young man's scythe runs between the third and fourth quarter of the painting.

From this axis a line is formed by the shaft of the scythe resting on the second harvester's shoulder. This is an important alignment which links the heads of the figures in the central group. The line then follows the curve of the blade, runs unseen behind the figures of the farmer, the woman and the baby until it emerges at the blade of the young harvester's scythe.

Karl Marx through the looking glass

It is not at all surprising that Lhermitte's artistic peers gazed at this career-launching painting in wonder when it was first exhibited at the important Salon de la Société des artistes français in Paris in 1882. Skilled painters could stand in front of this work and with their trained eyes savour all the subtleties we have discussed here and many that we haven't.

On its webpage for the painting, the Musée d'Orsay in Paris sums up some of the contemporary critical reactions to the work:

How can this success be explained?

Contemporaries saw in it sometimes a 'noble glorification of work' (Paul Leroy), sometimes a work full of 'sincerity' and even of 'truth'; Jules Claretie believed he detected in this work 'the calm grandeur of a biblical scene'.

Comment expliquer ce succès?

Les contemporains y virent tantôt une "noble glorification du travail" (Paul Leroy), tantôt une oeuvre pleine de "sincérité" et même de "vérité"; Jules Claretie crut déceler dans cette oeuvre "la grandeur calme d'une scène biblique".

Musée d'Orsay. Translation FoS.

Our readers have been invited to form their own views about the emotional narrative of this painting based simply on the evidence of their own eyes. Depending on their philosophical and cultural inclinations, each reader will come to a conclusion which is satisfying for them, whilst allowing that other reactions and interpretations are also permissible. Some degree of ambiguity is an essential feature of great works of art, which offer spaces in which the observer's own mind can be deployed.

Your author's unverifiable guess is that the reactions of modern readers will align quite closely with those of the Parisians who saw the painting in 1882. By any measure of skill, artistic cunning or entertainment value this painting is a cracker – shall we say, near faultless?

However, the final 'official' assessment of the painting by the Musée d'Orsay, in which the French Cultural Marxists put on their red-tinted spectacles in order to view the painting in its correct historical Marxist-Leninist context, should be a warning to us all.

We have already been alerted to what is to come with the peculiar question, 'How can this success be explained?', as though this wonderful painting is somehow so obviously defective that its 'success' requires 'explanation'.

Without doubt it would be fairer to see in it above all, the very image of the political ideal of a Third Republic based on a peasant world, symbol of peace and stability, order and work.

Sans doute serait-il plus juste d'y voir avant tout, l'image même de l'idéal politique d'une Troisième République prenant appui sur un monde paysan, symbole de paix et de stabilité, d'ordre et de travail.

Ibid. Translation FoS.

If this man's face with its exhausted, blank gaze represents 'the very image of the political ideal of a Third Republic', well, we might prefer to ask how this twisted, Olympian, 'fairer' viewpoint itself can be explained?

The face of the Peasant Woman Resting (above).

Easily, if you choose to see the artist as a useful, brainwashed idiot doing the bidding of a repressive establishment by deluding a simple, unenlightened bourgeois 'public at large':

With the purchase of 'Paying the Harvesters' by the state on the very opening day of the 1882 Salon, Lhermitte achieved fame and became one of the representatives of peasant painting under the Third Republic. From that moment, he specialised in chronicling the rural world until his death in 1925. Lhermitte was thus welcomed in the Salon as the long-awaited Messiah and the painting's impact on the public at large was immediate.

Avec l'achat de la 'Paye des moissonneurs' par l'Etat le jour même de l'ouverture du Salon de 1882, Lhermitte accède à la notoriété et devient un des représentants de la peinture paysanne sous la IIIe République. A partir de cette date, il se spécialise dans la chronique du monde rural, thème qu'il traitera jusqu'à sa mort, en 1925. Lhermitte est donc accueilli au Salon comme le Messie tant attendu. L'impact de cette oeuvre sur le grand public est immédiat.

Ibid. Translation: Musée d'Orsay.

[Note: the Third Republic in France is the period between the humiliating defeat of the country at the hands of the Prussians in 1870 and the humiliating defeat of the country at the hands of the Third Reich in 1940. It was a messily divided period in which the authorities seized on anything that might help to restore some sense of pride.]

Lhermitte, you fool, how could you not realise that you were just a useful tool for the authorities?

More glorification of the idyllic life of the peasant by Lhermitte? The Harvest, c. 1883. Watercolor sketch over traces of pencil. The man may have been the model for the seated harvester in La Paye des moissonneurs. Image: Cincinnati Art Museum.

The French gave us the phrase which best characterises this nonsense: de haut en bas, 'condescending'.

The experts at the Musée d'Orsay are so keen to push their view of the work as Establishment propaganda that they overlook the most obvious piece of evidence against this idea: the work is titled La Paye des moissonneurs, 'Paying the Harvesters', not simply 'The Harvesters', which is what we might expect for some scene of peasant life (the title of an earlier Lhermitte painting as it happens).

The central thrust of La Paye des moissonneurs is the act of payment, with all the economic and social implications which take us to the heart of the matter. There is a reason that the payment to the woman is located bang on a horizontal GR at the geometric centre of the composition. This fact and the precise title tell us exactly what this painting is about.

Unlike the looking-glass Rive gauche Cultural Marxist, the old school Marxist would have understood this immediately and would have had a lot of good things to say about this painting, if only to praise the way it highlights one of the central dichotomies of homo economicus: wages and labour.

Nevertheless, the old school Marxists had no sympathy either for this drifting human scum – the Lumpenproletariat, 'workers as unimportant as the rags they wear', they called them. They could not be organized, unionized or re-educated; they could not strike or rise up; they could not even read manifestos. For the purposes of the coming revolution they were useless dross, good only for the odd hunger riot at which – with a bit of luck – they might get killed in propaganda quantities by the forces of the crumbling state.

This de haut en bas state of mind also fits in with the fact that if the reader would like a high-resolution version of this beautiful painting he or she is not going to get it from the Musée d'Orsay, which is one of those galleries which hoard their treasures jealously, only allowing a quick glimpse to the paying visitor of something which is, after all, public property.

A Gollum-like possessiveness, a neo-Marxist disdain for the subject of the work and a contempt for today's proletarians who, duped by their false consciousness, unashamedly enjoy looking at this beautiful painting are among the reasons why the work is not as well-known on the web as it should be. Where it is to be found, then usually in terrible, gamma-distorted images.

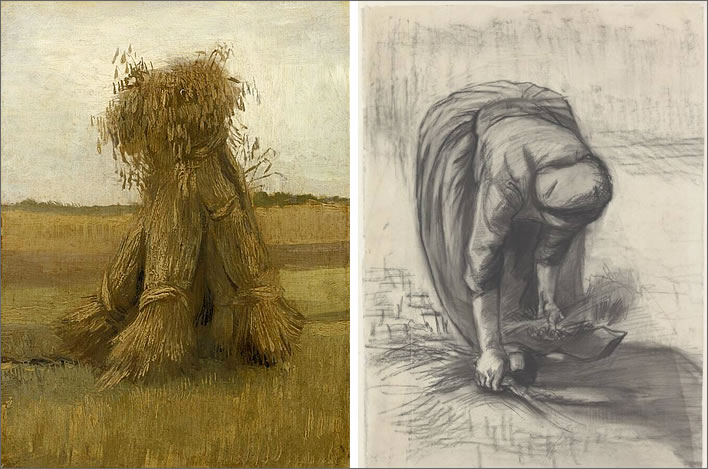

In responding to this painting, readers should trust their instincts. They might just find out that their instincts are shared with none other than Vincent van Gogh, whose opinion in matters of the visual arts must be respected. After seeing La Paye des moissonneurs he wrote to his brother Théo in 1885:

It is certain that for years I have not seen anything as beautiful as this scene by Lhermitte

[…]

Lhermitte preoccupies me too much tonight for me to write about anything else.

When I think about Millet or Lhermitte, I believe that modern art is just as powerful as the work of Michelangelo or Rembrandt.

Il est certain que depuis des années je n'ai rien vu d'aussi beau que cette scène de Lhermitte…

Lhermitte me préoccupe trop ce soir pour continuer à parler d'autre chose.

Quand je songe à Millet ou à Lhermitte, je trouve l'art moderne aussi puissant que l'oeuvre de Michel-Ange ou Rembrandt.

Ibid. Translation FoS

Vincent van Gogh, the painter who defined rural labour for the modern age:

Two pieces by van Gogh from 1885, the year of his letter to his brother Théo. Left: Korenschoven, 'The sheaf of corn'; right: Arenlezende Boerin, 'Peasant woman gathering ears of corn'. Images: Kröller-Müller Museum.

No false consciousness there.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!