Goethe's Römische Elegien V-VIII

Richard Law, UTC 2020-10-21 06:42

V Laß dich, Geliebte, nicht reun, daß du mir so schnell dich ergeben [3]

Laß dich, Geliebte, nicht reun, daß du mir so schnell dich ergeben!

1Glaub es, ich denke nicht frech, denke nicht niedrig von dir.

Vielfach wirken die Pfeile des Amors: einige ritzen,

3Und vom schleichenden Gift kranket auf Jahre das Herz.

Aber mächtig befiedert, mit frisch geschliffener Schärfe

5Dringen die andern ins Mark, zünden behende das Blut.

In der heroischen Zeit, da Götter und Göttinnen liebten,

7Folgte Begierde dem Blick, folgte Genuß der Begier.

Glaubst du, es habe sich lang die Göttin der Liebe besonnen,

9Als im Idäischen Hain einst ihr Anchises gefiel?

Hätte Luna gesäumt, den schönen Schläfer zu küssen,

11O, so hätt ihn geschwind, neidend, Aurora geweckt.

Hero erblickte Leandern am lauten Fest, und behende

13Stürzte der Liebende sich heiß in die nächtliche Flut.

Rhea Silvia wandert, die fürstliche Jungfrau, den Tiber,

15Wasser zu schöpfen, hinab, und sie ergreifet der Gott.

So erzeugte die Söhne sich Mars! — Die Zwillinge tränket

17Eine Wölfin, und Rom nennt sich die Fürstin der Welt.

Have no regrets, Beloved, that you yielded to me so quickly! Believe me that I do not think insolently, do not think less of you.

Cupid's arrows work in many different ways: some scratch the surface and slow poison over the years sickens the heart.

But, powerfully feathered and freshly sharpened, others penetrate to the marrow, inflaming the blood.

In heroic times, when gods and goddesses loved, desire followed the gaze, pleasure the desire.

Do you believe that the goddess of love reflected long, when she saw Anchises in the grove of Mount Ida?

Had Luna neglected to kiss the beautiful sleeper, O, jealous Aurora would have wakened him soon after.

Hero glimpsed Leander at the noisy feast and without delay the lover sprang hotly into the night-time torrent.

Rhea Silvia, virgin princess, went down to the Tiber to fetch water and the god seized her.

So Mars created the sons! – a she-wolf suckled them, and Rome called itself the princess of the world.

Notes

so schnell dich ergeben: G.'s treatment of the idea of the woman surrendering too quickly may have come from Tibullus, who had some helpful advice for hesitant girls – helpful for the man, that is:

It is touching the body which does the harm, the lingering kiss, wrapping thigh around thigh. But do not make it difficult for your young man to win you – Venus will punish such a sad deed.

Sed corpus tetigisse nocet, sed longa dedisse / Oscula, sed femori conseruisse femur. / Nec tu difficilis puero tamen esse / memento: / Persequitur poenis tristia facta Venus.

Tibullus 1.8:25-28.

Folgte Begierde dem Blick, folgte Genuß der Begier: Alluding to Ovid, Fasti, 3.21: Mars videt hanc visamque cupit potiturque cupita, 'Mars saw her, desired the seen and enjoyed the desired'.

im Idäischen Hain einst ihr Anchises gefiel: The beautiful young man Anchises was herding sheep in the groves of Mount Ida when he was seen by Aphrodite/Venus. Her look turned into desire and her desire turned into immediate action: the child of the coupling was the Trojan hero Aeneas.

Luna gesäumt, den schönen Schläfer zu küssen: The 'beautiful sleeper' was the gorgeous Endymion. The moon goddess Selene/Luna kept him in a permanent sleep in a cave, which she visited every night, producing in the end 50 daughters. Had Luna not visited him, the jealous dawn goddess, Aurora, would have wakened him for herself.

Hero erblickte Leandern: Hero was a mortal, a priestess of Aphrodite/Venus. The saw each other at a feast, which led to Leander's famous nightly swimming feat across the swift current of the Hellespont.

Rhea Silvia: was a daughter of a king. She became a vestal virgin, pledged to chastity. Mars saw her whilst she was fetching water from the river and, as usual, the look led to the desire etc., which all led to the birth of the founders of Rome, the twins Romulus and Remus.

Fürstin der Welt: a wordplay on Rhea Silva, the princess, and Roma, the princess.

Commentary

Leaving aside the numerous mythological allusions, this elegy requires little comment: it is simply a justification for uninhibitedly following natural desires to their natural conclusions: see—desire—take. At least superficially, Goethe is washing out the cultural and religious stain of the 'easy woman' and simultaneously attacking the prudish chastity of his own day.

It is probably prudent in this #meToo age to point out that the majority of the Classical allusions here are cases of powerful women (goddesses) having their way with helpless mortal men. Prudent, also, to point out that Goethe did not simply ravish his Roman love: she gave in to him of her own free will instead of (as the text makes clear) playing hard to get for as long as she wished. There are, however, some considerations that lie behind this simple situation.

Her mother appears to have been not just complicit in her daughter's affair with Goethe but to have actively encouraged the liason with the well-heeled German artist. It appears that both she and her daughter never learned Goethe's real name: to them he was someone called Johann Philippe Möller. The mother was the chaperone when propriety required one, who absented herself as and when expediency required it. She was herself a widow and the male guardian or paterfamilias was a brother or brother-in-law.

What were her daughter's prospects in practice? Marriage at the time (in Rome and many other places) was primarily a financial transaction, not an emotional liason (as Goethe told Carl August); Goethe's own deep-seated aversion to marriage appears to have arisen from its dominant legal and financial framework at the expense of love and emotion. The shine comes off such purity of passion when we consider that the affair took place under Goethe's assumed name: however good the sex was, he did not drop his guard.

Once more we encounter the Odyssean model in Goethe: the cautious, reflective hero who never rushes in; his shipmates blunder into the witch Circe's lair, whereas he stops well ahead, has a think about it all, has a chat to Hermes, and only goes in when he has the herb that will protect him from her spells.

The impoverished young Roman widow with the small child had almost certainly no attractive dowry to offer and was thus a loser in the conventional marriage market. We can expect that her education would have been meagre – Zapperi suggests that she would have been borderline illiterate – her only source of income would come from doing something such as sewing, cleaning or taking in washing. Her uncle, unless he was exceptionally well-off, would certainly not be willing to extend himself financially to get her married off for the second time.

Her mother's instincts were correct: as far as we can know in the cloud of unknowing that envelops their affair, Goethe treated his lover well and generously, leaving her a substantial sum on his departure. Also as far as we know, no pregnancy or lasting commitment ensued, so we can state with some confidence that the girl was better off for the four months of German poet she had.

VI Fromm sind wir Liebende, still verehren wir alle Dämonen [4]

Fromm sind wir Liebende, still verehren wir alle Dämonen,

1Wünschen uns jeglichen Gott, jegliche Göttin geneigt.

Und so gleichen wir euch, o römische Sieger! Den Göttern

3Aller Völker der Welt bietet ihr Wohnungen an,

Habe sie schwarz und streng aus altem Basalt der Ägypter,

5Oder ein Grieche sie weiß, reizend, aus Marmor geformt.

Doch verdrießet es nicht die Ewigen, wenn wir besonders

7Weihrauch köstlicher Art einer der Göttlichen streun.

Ja, wir bekennen euch gern: es bleiben unsre Gebete,

9Unser täglicher Dienst Einer besonders geweiht.

Schalkhaft, munter und ernst begehen wir heimliche Feste,

11Und das Schweigen geziemt allen Geweihten genau.

Eh’ an die Ferse lockten wir selbst durch gräßliche Taten

13Uns die Erinnyen her, wagten es eher, des Zeus

Hartes Gericht am rollenden Rad und Felsen zu dulden,

15Als dem reizenden Dienst unser Gemüt zu entziehn.

Diese Göttin, sie heißt Gelegenheit, lernet sie kennen!

17Sie erscheinet euch oft, immer in andrer Gestalt.

Tochter des Proteus möchte sie sein, mit Thetis gezeuget,

19Deren verwandelte List manchen Heroen betrog.

So betrügt nun die Tochter den Unerfahrnen, den Blöden:

21Schlummernde necket sie stets, Wachende fliegt sie vorbei;

Gern ergibt sie sich nur dem raschen, tätigen Manne,

23Dieser findet sie zahm, spielend und zärtlich und hold.

Einst erschien sie auch mir, ein bräunliches Mädchen, die Haare

25Fielen ihr dunkel und reich über die Stirne herab,

Kurze Locken ringelten sich ums zierliche Hälschen,

27Ungeflochtenes Haar krauste vom Scheitel sich auf.

Und ich verkannte sie nicht, ergriff die Eilende: lieblich

29Gab sie Umarmung und Kuß bald mir gelehrig zurück.

O wie war ich beglückt! — Doch stille, die Zeit ist vorüber,

31Und umwunden bin ich, römische Flechten, von euch.

We are pious, we lovers, we quietly worship all spirits, we want every god and every goddess to be well disposed towards us.

And so we resemble you, O Roman conquerors! You who offer a home to the gods of all peoples,

Whether they come black and severe from the ancient basalt of the Egyptians, or white and attractive in marble sculpted by a Greek.

Nor does it annoy the immortals, should we scatter incense of the most expensive sort to one of them in particular.

Yes, we happily admit to you that our prayers, our daily observances, are consecrated to one goddess in particular.

Impertinently, cheerfully and seriously we perform discreet celebrations, and all the initiated are pledged equally to secrecy.

Instead of attracting the Furies to our heels as a result of horrible deeds, we would rather risk having to suffer

the harsh judgement of Zeus with rolling wheel and rocky cliffs, rather than having to withdraw our hearts from the delightful service [of the goddess].

This goddess is called 'Opportunity', get to know her! She appears to you often, always in a different form.

She must be the daughter of Proteus, conceived with Thetis, whose mutation tricks deceived many heroes.

Now the daughter cheats the inexperienced, the stupid: she teases sleepers and flies past the wake.

She gives herself happily to the decisive man of deeds, who finds her docile, playful and tender and benevolent.

She has sometimes appeared to me, a brownish girl, whose hair fell dark and rich over her forehead,

Short curls wrapped around her beautiful neck, unbraided hair curled up from the parting.

And I did not overlook her presence, but seized the hurrying one: gently she soon gave me embraces and kisses back with advantage.

O how happy I was! — but still, the moment has passed, and now I am encircled, Roman braids, by you.

Notes

Fromm: 'pious', 'reverent'. G.'s little joke should not go unremarked – we expect 'pious' to apply to one religion or deity, not as here, to be applied to an attitude of reverence to all deities. A big tent, in other words.

Dämonen: 'demons'. G. is using the word in the Classical sense, in which these agents of the gods can be good as well as bad, not the modern Christian sense of things of the devil, i.e. 'demonic'.

den Göttern aller Völker der Welt: 'the gods of all the peoples of the world'. The Ancient Romans were an intensely superstitious people who absorbed many mythic elements from their vassals. G.'s use of the word Wohnungen echoes the famous (though cryptic) passage in John/Johannes 14:2, in Luther's words: In meines Vaters Hause sind viele Wohnungen, in the Authorised King James version 'In my Father’s house are many mansions'.

Weihrauch köstlicher Art: Some readers may have an idea what this 'incense of the most expensive sort' that is 'scattered to one particular goddess' is. Probably best to keep that knowledge to yourselves, though.

heimliche Feste…das Schweigen geziemt allen Geweihten genau: Consenting adults in private – no one talks about these acts of worship, of course, so they are comparable to the hermetic Eleusinian Mysteries.

die Erinnyen: the Furies, who inescapably pursued and revenged wrongdoing, the 'horrible deeds'. Their characteristic mode was a pursuit from which there was no escape, hence G.'s apposite use of 'on our heels'.

lockten…wagten: These verbs are not in the past tense, they are in the Konjunktiv II, usually known in English in terms such as the 'hypothetical conditional', that is, expressing some hypothetical state.

des Zeus hartes Gericht am rollenden Rad und Felsen: Ixion murdered his father-in-law, an act which brought him opprobrium and suffering, deserving of the attention of the Furies. Zeus took pity on him and brought him into his house. There Ixion took advantage of his host and made moves on Zeus's wife Hera/Juno. Zeus blasted him from Olympus into the nether regions, where he caused him to be fastened to a burning wheel that turned ceaselessly.

In the Prometheus myth, Prometheus stole fire from Zeus and gave it to humans. Zeus punished him by shackling him to a rocky cliff and having an eagle devour his liver. Once devoured, the liver grew again so that the eagle could start on him once more.

Gelegenheit: 'opportunity'. The mythological figure of Kairos (Gk), Occasio (L), 'Opportunity'.

ein bräunliches Mädchen: Goethe's pseudo-eyewitness description of the goddess Kairos corresponds generally with the traditional iconography. The common point is her attractive and extensive hair when seen from the front compared with the rear half of her head, which is completely bald. The visual metaphor is of a goddess who can be seized by the hair when she approaches, but when she has passed there is nothing more to grasp and the opportunity is gone forever. This is cognate with Horace's carpe diem, 'seize the day'. Even in modern German there is a saying Die Gelegenheit beim Schopf fassen, 'grasp the chance by the hair'.

Umarmung und Kuß: 'embraces and kisses'. The goddess Kairos metamorphoses into the figure of the loved one.

die Zeit ist vorüber: Kairos, whose core property is time, has passed by.

römische Flechten: 'Roman braids', in the metamorphosis of the goddess Kairos into G.'s Beloved, the hair, so carefully described by G., is the mechanism of the transition.

Commentary

In the preceding elegy Goethe set out the arguments for the spontaneity of sexual lust: see–desire–take.

In the present elegy he has added an additional vector to the dynamic: seizing the moment to achieve that fulfilment, seizing the goddess Opportunity as she passes.

We must never forget that shortly after Goethe's return to Weimar in 1788, he met Christiane Vulpius. There followed an intense affair which developed rapidly. Thus, at the time he was writing his Römische Elegien his passionate affair with Christiane overlaid in its immediacy his time with his Roman lover.

We should therefore never assume that his 'Roman poems', written in Weimar, are exclusively about his Roman holiday romance, though that may be what the title of the collection suggests.

Goethe spent his literary career misleading and mystifying his readers in one way or another: seemingly autobiographical pieces were as carefully constructed and mystified as everything else in his writings.

Thus, his rapid conquest of Christiane Vulpius fits perfectly into the anacreontic mood of Elegy V (see-desire-take) and Elegy VI (seize the opportunity). By redirecting his current passionate experiences with Christiane on to the proxy of his nameless Roman lover, he is also defusing the scandalous liaison with Christiane which brought him so much criticism, particularly from the Weimar court.

VII Froh empfind ich mich nun auf klassischem Boden begeistert [5]

Froh empfind ich mich nun auf klassischem Boden begeistert,

1Vor- und Mitwelt spricht lauter und reizender mir.

Hier befolg ich den Rat, durchblättre die Werke der Alten

3Mit geschäftiger Hand, täglich mit neuem Genuß.

Aber die Nächte hindurch hält Amor mich anders beschäftigt;

5Werd ich auch halb nur gelehrt, bin ich doch doppelt beglückt.

Und belehr ich mich nicht, indem ich des lieblichen Busens

7Formen spähe, die Hand leite die Hüften hinab?

Dann versteh ich den Marmor erst recht: ich denk und vergleiche,

9Sehe mit fühlendem Aug, fühle mit sehender Hand.

Raubt die Liebste denn gleich mir einige Stunden des Tages,

11Gibt sie Stunden der Nacht mir zur Entschädigung hin.

Wird doch nicht immer geküßt, es wird vernünftig gesprochen,

13Überfällt sie der Schlaf, lieg ich und denke mir viel.

Oftmals hab ich auch schon in ihren Armen gedichtet

15Und des Hexameters Maß leise mit fingernder Hand

Ihr auf den Rücken gezählt. Sie atmet in lieblichem Schlummer,

17Und es durchglühet ihr Hauch mir bis ins Tiefste die Brust.

Amor schüret die Lamp’ indes und gedenket der Zeiten,

19Da er den nämlichen Dienst seinen Triumvirn getan.

I now find myself happy and full of enthusiasm on classical soil, the antique and the contemporary worlds speak to me louder and more stimulatingly to me.

Here I follow the counsel, leaf through the works of the ancients with a busy hand, with new enjoyment every day.

But through the nights Cupid keeps me busy in other ways; if I am only half the wiser, I am though twice as blessed.

And do I not educate myself, in that I see the form of the delightful bosom and my hand glides down the hips?

For only then do I understand marble properly: I think and compare, see with a feeling eye, feel with seeing hand.

Though the loved one may rob me of some hours of the day, she gives me hours of the night as compensation.

There is not always kissing, there is sensible conversation, if sleep overcomes her, I lie there and think of much.

I have often composed verse in her arms, my fingering hand quietly counting the hexameter's measure

on her spine. She breathes in gentle sleep, and her breath burns deeply into my breast.

Cupid trims the lamp all the while and thinks of the times when he performed the same service for his triumvirate.

Notes

befolg ich den Rat: the 'counsel/advice' is taken to be an allusion to Horace, De Arte Poetica, 268: vos exemplaria Graeca nocturna versate manu, versate diurna, 'took into my hand the Greek models and studied them incessantly by night and by day'.

halb nur gelehrt: 'only half educated', the hours of dalliance with the Beloved eat into G.'s self-education programme.

des Hexameters Maß…auf den Rücken gezählt: In this, the best-known and most commentated elegy in the Römische Elegien, we find the most famous image of the collection: G., awake whilst his lover sleeps in his arms and inspired to post-coital versifying is counting the poetic measures of the distich on the spurs of her spine. It is indeed a beautiful and romantic image, just the sort of thing we expect from our poets. Unfortunately, in the hard light of the real world, the situation is quite difficult to understand.

Using an anorexic, anything is possible, but for everyday humans the spurs of the seven cervical vertebrae and those of the five lumbar vertebrae are difficult to find, let alone count – certainly not without the sort of probing that would wake someone up.

The thoracic vertebrae are more accessible and there are twelve of them in all, but many of them are also uncountable in normal humans. Perhaps your author should try to make the acquaintance of scrawnier women – some website must exist for that: 'My hobbies: "counting vertebrae"' (that will drag 'em in) – but in the absence of empirical data, he remains sceptical of G.'s ability to count up to more than three or four on a sleeper's back without waking the victim up. 'O, non di nuovo Jean Philippe! Che uomo!'

In Elegy IV we are told that, since meeting her German poet, she's now eating better – which fact may lend some credence to our scrawny hypothesis.

Leaving that problem to one side, the next step we grumbling sceptics take is to ask just what it is that G. is counting here. G. tells us that he is counting the 'hexameter's measure', which would mean six feet (or five for the second line of the distich, the pentameter). G.'s metrical interpretation of the distich is as follows:

Oftmals | hab ich | auch schon | in ihren | Ar men ged | ichtet

Und des Hex | ameters | Maß ¦ leise mit | fingernder | Hand

There are 14 syllables in each line. The long syllables are marked in blue, the short in green. He clearly can't be counting syllables, because he would run out of palpable vertebrae.

The first line, the hexameter, has six feet, as its name implies, the second line, the pentameter, has five feet, also as its name implies. In this example, the pentameter has the same number of syllables as the hexameter, but its speciality, the caesura, here marked in violet takes up four, not two syllables. The line is 'catalectic', that is, it is lacking a syllable at the end to complete the metrical foot.

This is not quite the whole story, as you might expect in our world of endless complications. Traditional distichs should really have dactyls (— ◡ ◡), not trochees (— ◡), but German is not Greek or Latin, so we have to cut the poets in that language a bit of slack, given what they have to work with (English is even worse, though). Generalising, the rule for the German distich is 'a dactyl if you can, a trochee if you need to'. In this example, G.'s hexameter is very trochaic, but his pentameter is much more dactylic.

Your author finds counting these metric feet on some row of protuberances (a keyboard will do if no compliant human is available) quite difficult – but then he is not Goethe. Readers should try it for themselves: the internet is full of beautiful people with eminently countable vertebrae and the YouTube viral video is just waiting to be made. Stay classy!

seinen Triumvirn: G.'s triumvirate here consists of the three Augustan writers of love elegies, Catullus, Tibullus and Propertius. On his return from Rome in 1788, G. was sent a book by his old friend Karl Ludwig von Knebel Catullus, Tibullus, Propertius ad fidem optimorum librorum denuo accurate recensiti. Adiectum est Pervigilium Veneris from 1762. This gift of Knebels can be thought of as the moving spirit behind the Römische Elegien. G. called it his Kleeblatt der Dichter, his 'clover leaf of poets'.

We find relatively little of Catullus in G.'s elegies, but much more from the mythologising Ovid. As a result, some scholars, who will always find something over which to argue, think it more realistic that Ovid should be substituted in this 'triumvirate'. Propertius' dominance in the 'clover leaf' is probably due to the fact that Knebel was at that moment working on a prose translation of the Propertian elegies, a handy crutch for the poet in a hurry. We could assume that G.'s inspiration was in fact a four-leafed clover.

Commentary

Where the Römische Elegien are discussed and commented, then it is the present elegy which almost always serves as the text.

This is no surprise. This elegy is erotic, but palatably so, never having had to be excluded from the core collection of 20 elegies on the grounds of extreme indecency; the sex is moderated as a facet of civilised behaviour: 'there is sensible conversation'.

This elegy is also largely self contained, requiring the study of none of the other elegies for its interpretation. Also, unlike some of the other elegies, it demands little scholarship – its readers are not required to follow threads into the labyrinth of classical literature. But above all it is a masterpiece of poetic skill that is still accessible to the non-specialist, full of haunting imagery and clever invention.

Even though it needs no extensive interpretation, your author's inner drudge insists on a few remarks.

Note, for example, the dancing thread of hand and eye, seeing and feeling, that winds through the poem: the busy hand [turning pages], the exploring hand taking in the lines of hips and thighs, the fingering hand on the verterbrae, the seeing hand of the eyeless observer, even the allusion to Horace finds that poet busy with his hands; the eye takes in the form of the bosom, 'feels' the plasticity of what it sees. There is a reason that this kind of thing is called 'sensual'.

When both hand and eye, flesh and stone come together, only then does Goethe 'understand' marble. This elegy is an encomium to first-hand experience as the basis for artistic understanding. Goethe is not looking at engravings in books but at palpable, real objects on classical soil. He tells us in Dichtung und Wahrheit that his vertigo cure on the spire of Strasbourg Minster stood him in good stead when he was clambering over Roman monuments, measuring, observing and taking notes, often dangling precariously from windows and ledges.

His life-long scientific interests are proof of his first-hand encounter with the objective world, but even without them, we would find the same empirical spirit in his poetry, that spirit of enquiry which raises Goethe head, shoulders and rump above the many mediocrities of the time.

In this, once again, Goethe is his own man, his own poet. Just when the German literary world was trembling on the brink of the Romantic Movement (a.k.a.'making elevating stuff up'), Goethe was getting down and dirty around the deep roots of Western civilisation, taking his measurements, making his observations, finding his puella, his donna, his Mädchen and writing about her in a way that no one had dared to do since people last felt able to write anacreontics.

Another of Goethe's great skills is his ability to generate captivating images in his poetry: the erotic physicality of exploring the lover's body, the hexameters counted on her spine, her breath on his chest, the flickering oil-lamp in the dark room, tended by Cupid, as the helpful lad tended oil-lamps nearly two millennia before for those other Roman poets – invoking a remarkable fellowship of poetic solidarity.

VIII Kannst du, o Grausamer, mich mit solchen Worten betrüben [6]

„Kannst du, o Grausamer, mich mit solchen Worten betrüben?

1Reden so bitter und hart liebende Männer bei euch?

Wenn das Volk mich verklagt, ich muß es dulden! und bin ich

3Etwa nicht schuldig? Doch ach! Schuldig nur bin ich mit dir!

Diese Kleider, sie sind der neidischen Nachbarin Zeugen,

5Daß die Witwe nicht mehr einsam den Gatten beweint.

Bist du ohne Bedacht nicht oft bei Mondschein gekommen,

7Grau, im dunklen Surtout, hinten gerundet das Haar?

Hast du dir scherzend nicht selbst die geistliche Maske gewählet?

9Soll’s ein Prälate denn sein — gut, der Prälate bist du!

In dem geistlichen Rom, kaum scheint es glaublich, doch schwör ich:

11Nie hat ein Geistlicher sich meiner Umarmung gefreut.

Arm bin ich, leider! und jung, und wohlbekannt den Verführern:

13Falconieri hat mir oft in die Augen gegafft,

Und ein Kuppler Albanis mich mit gewichtigen Zetteln

15Bald nach Ostia, bald nach den vier Brunnen gelockt.

Aber wer nicht kam, war das Mädchen. So hab ich von Herzen

17Rotstrumpf immer gehaßt und Violettstrumpf dazu.

Denn „ihr Mädchen bleibt am Ende doch die Betrognen”

19Sagte der Vater, wenn auch leichter die Mutter es nahm.

Und so bin ich denn auch am Ende betrogen! Du zürnest

21Nur zum Scheine mit mir, weil du zu fliehen gedenkst.

Geh! Ihr seid der Frauen nicht wert! Wir tragen die Kinder

23Unter dem Herzen, und so tragen die Treue wir auch;

Aber ihr Männer, ihr schüttet mit eurer Kraft und Begierde

25Auch die Liebe zugleich in den Umarmungen aus!”

Also sprach die Geliebte und nahm den Kleinen vom Stuhle,

27Drückt ihn küssend ans Herz, Tränen entquollen dem Blick.

Und wie saß ich beschämt, daß Reden feindlicher Menschen

29Dieses liebliche Bild mir zu beflecken vermocht!

Dunkel brennt das Feuer nur augenblicklich und dampfet,

31Wenn das Wasser die Glut stürzend und jählings verhüllt;

Aber sie reinigt sich schnell, verjagt die trübenden Dämpfe,

33Neuer und mächtiger dringt leuchtende Flamme hinauf.

'How can you, O cruel one, distress me with such words? Do male lovers speak so bitter and hard where you come from?

When people accuse me, I have to put up with it! And if I am perhaps not guilty? But of course! I am only guilty because of you!

These clothes are the evidence for the envious female neighbour that the widow no longer weeps alone for the husband.

Have you not recklessly come here by moonlight, grey, in a dark cape, your hair bound up behind?

Did you not yourself choose to wear this priestly costume? If it is to be a prelate – good, then you are the prelate!

In priestly Rome, difficult though it is to believe, yet I swear it: no priest has ever shared my embrace.

I am poor, unfortunately! and young and known to the seducers: Falconieri has often gazed into my eyes,

And Albani's pimp enticed me with important notes once to Ostia, once to the Quattro Fontane.

But the one person who did not turn up was the girl. Thus I have always hated deeply both the red and the violet stockings.

For "In the end you girls are always the cheated ones" my father said, though my mother took it more lightly.

And so in the end I have indeed been cheated! You are just affecting anger at me, because you are thinking of leaving me.

Go! You are unworthy of women! We carry the children under our hearts, and carry loyalty there, too;

But you men, you ejaculate love along with your power and lust in the embrace!'

Thus spoke the Beloved and picked up the little one from the chair, kissed him as she pressed him to her heart, tears welled up from her eyes.

And how I sat there in shame, that the gossip of hostile people had managed to besmirch this beautiful image!

The fire burns dimmer only for a moment and steams, when a splash of water suddenly wraps the glowing embers in steam.

But the embers quickly purify themselves, drive out the beclouding steam, the bright flame forces more freshly and more powerfully upwards.

Notes

das Volk mich verklagt: ~'people gossip about me'.

Schuldig nur bin ich mit dir: i.e. of all the things of which the gossips now accuse her, only her liason with G. is true.

die Witwe: We now learn that G.'s loved one is a young widow.

dunklen Surtout: a dark overcoat or cape, traditionally worn by Roman clerics.

scherzend nicht selbst die geistliche Maske: Maske here is best interpreted as a 'costume', not a mask as such. Goethe's choice of a priestly disguise for his nightly visits to the young widow may have appealed to his sense of humour (scherzend) but it was not unproblematic for the young woman, whose nosy neighbours took the shadowy figure in the moonlight to be a priest – not unusual in Rome, the capital of priestly fornication, but a wandering German poet as a lover might have been a better choice.

der Prälate bist du: 'You are the preferred one'. A prelate is a bishop or other high ecclesiastical dignitary. The word ultimately derives from the Latin past participle praeferre, as in the English 'the preferred one'. Goethe is playing on words cleverly.

Falconieri: The name of a noble Roman family (see Elegy II).

Albani: The name of an important Roman family, in G.'s time represented in the person of Cardinal Alessandro Albani. We can assume that Goethe was familiar with the role the Albani family played in the work of Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), the reinterpreter of classical art for the 18th century. Winckelmann occupied a generous four-roomed apartment on the upper floor of the Albani Palace, the one by the Quattro Fontane. Cardinal Allesandro Albani (1692-1779) was a passionate lover of and collector of antique art, whose collection was one of the greatest in Rome.

nach den vier Brunnen gelockt: 'the four fountains', The Piazza delle Quattro Fontane in Rome. The Palazzo Drago-Albani was located on this square.

Rotstrumpf…Violettstrumpf: Cardinals wore red stockings, bishops wore violet stockings.

wenn auch leichter die Mutter es nahm: Whereas the father was very protective of his daughter, the mother took it more calmly or pragmatically. This statement is one of the clues we have that the mother of G.'s beloved was relaxed about his liaison with her daughter and probably even complicit in promoting it.

nahm den Kleinen: We learn here that not only is G.'s loved one a widow, she has a young son.

Reden feindlicher Menschen: ~'the gossip of hostile people'. G.'s deep mortification at having succumbed to the malignant influence of gossip in respect of his lover is made worse when we consider the amount of gossip he had himself to endure at the court in Weimar.

This gossip was at its peak when G. was writing the Römische Elegien: just after his return to Weimar he became involved in a scandalous relationship with the 23 year-old Christiane Vulpius – effectively his concubine, according to the moral understanding of those times – a brazen relationship that even produced five illegitimate children (four of whom died in infancy, however).

The bitter example in the elegy of the damage gossip and rumour can do is a foretaste the allegorical treatment of rumour in Elegy XXII.

However, G. is creating this complex elegy not only to demonstrate the dangers of gossip and his own susceptibility to it, but also to display the moral probity of his beloved. She may be sharing a bed with him and may even be enjoying monetary benefits, too, but, certainly in Roman terms, she is morally upstanding. She is no lady of the night or working girl. G.'s ability to rely on her fidelity and sexual rectitude (her sichere Küsse) will become a central point in Elegy XXI.

die trübenden Dämpfe: trüb(e) is normally used to describe liquids that are in some way unclear: 'cloudy', 'milky' etc. Here the bright flame [of love] is beclouded by steam, a symbol for the current mood between the two lovers. G.'s use of 'trüb' here to close the elegy is not fortuitous, for we find at the very beginning of the elegy that the woman's mood has been betrübt, 'beclouded' by G.'s words.

Commentary

On the surface, Goethe's honesty in exposing his own foolishness in this elegy might seem to be impressive. We gather that his nightly antics disguised as a cleric have led to gossip that his loved one is consorting with some prelate or other. The rumour has now come back to G.'s ears, leading him, it appears, to accuse his lover of having liaisons with priests during their relationship.

Rejecting these accusations, the woman explains to Goethe that not only is he the only one in her life at the moment, and not only has she rejected several priestly propositions in the past, but that G., by his great joke of disguising himself as a priest, is himself the cause of the gossip. The misunderstanding may rebound on Goethe to his disadvantage, but his loved one comes out of the incident in a very good light, with honour and probity intact.

Before we get bogged down in the details of this elegy, let us just stand back and take a moment to admire its genius: it is a perfect evocation of what we might term the 'drama of manners' that we find in the Latin elegaists who are the tutelary deities behind the Römische Elegien. This elegy could have been written by Catullus, Propertius or Tibullus. It is the enactment of a dramatic scene which, beneath its surface, is freighted with meaning and nuance.

Readers familiar with English poetry might think of Robert Browning (a fine classicist) and his 'dramatic monologues' – imagined incidents with (often) imagined characters which illuminated themselves, their times and some generality of human behaviour. Opening his monster poem Sordello (1840) he cast himself in the role of the magician who can conjure up the past (with built in drum-roll): 'Only believe me. Ye believe? / Appears / Verona…'. The characters in his 'dramatic' works wear the masks of the dramatis personae; Browning even gathered a collection of poems together under that title.

Goethe, too, was a master of artifice – more Mephistopheles than Faust – and a practitioner of distance and masking: his characters, too, like Browning's, wear the masks of the dramatis personae – the accused woman, the foolish lover, the corrupt prelate. We must always treat his works as creations held at arm's-length from his 'true' self – as mask wearers, in other words. Readers who want to follow the rabbit down this hole could do worse than start with Goethe's poem Ilmenau (1783), in which he encounters the shade of his youthful self.

But we have no time to do this here. We merely note that in this elegy, Goethe has written in German at the end of the 18th century an evocation of a first century BC Latin elegy; an invocation and evocation which Browning and the more thoughtful modern poets would have understood. What he has done is not just mimicry or parody: he has advanced the genre by adding a layer of nuanced generality to the superficial action.

For this reason we have to issue once more our Goethe health warning at this point. We repeat, the scene presented here is a product of artifice, not narrative accuracy. It may never have taken place at all. It appears to be a fiction that is to be used as a vehicle for tackling the twin subjects of rumour and propriety. In the high emotion of the scene into which we intrude just after Goethe has made his accusations to his lover (which he do not hear), the woman's speech is a fine rhetorical construct which flows from the poet's pen, not the mouth of a hurt and angry person.

Browning et al. may have understood what Goethe was at, but when Goethe's contemporaries were confronted with the expurgated collection of twenty elegies published in Horen in 1795 their reactions revealed the state of the official culture that surrounded Goethe in Weimar. Goethe had brought back a basket of strange fruits from a distant country and a distant time and his contemporaries had no idea how to eat them.

Charlotte von Stein (1742-1827), Goethe's friend for a decade until he found Christiane Vulpius in 1788, wrote to Charlotte Schiller on 27 July that she had für diese Art Gedichte keinen Sinn, 'no appreciation of this sort of poem' (or perhaps better 'no time for…'). Only one elegy appealed to her a little, the present elegy (Elegy 6 in the Horen), for only there did she find some innigeren Gefühl, 'inner feeling'.

She had been raised in the poetic tradition of Empfindsamkeit, 'sensibility' and her brain was now prepared for the coming of the German Romantics with their feelings aplenty. Goethe's distanced invocations and evocations of Augustan irony were beyond her understanding.

August Wilhelm Schlegel (1767-1845), a co-editor of Horen, wrote an encomium to the Römische Elegien which tells us more about his own limitations (despite his impressive credentials) than it does about the work. For example:

The sixth elegy stirs the heart by its truthfulness; the seventh entrances the imagination through heavenly radiance. Among the heroes who would buy the bed of love with their fame, (elegy 10), it would have been better not to have mentioned Frederick the Great.

Die 6te El. rührt das Herz durch ihre Wahrheit; die 7te bezaubert die Phantasie durch überirdischen Glanz. Unter den Helden, welche das Lager der Liebe mit ihrem Ruhm erkaufen würden, (10.El.) wäre Friedrich der Große vielleicht schicklicher nicht genannt.

August Wilhelm Schlegel in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, No. 4, January 1796.

August Wilhelm Schlegel and his brother Friedrich (1772-1829) would become the leading theoreticians of the German Romantik Schule. Goethe and his Römische Elegien were years ahead of them all in the use of irony and the maintenance of the Augustan poetic persona. Heinrich Heine (1797-1856), the great ironist of his age, mocked the Schlegels and their Romantic companions soundly for their wishy-washy idiosyncrasies.

The reasons for Goethe's paranoia over his lover's fidelity become clearer in two of the later elegies, Elegy XVII, the 'syphilis elegy' and Elegy XXI, the 'safe sex' elegy. Without her fidelity he was always at risk of a venereal infection – in the worst case, syphilis. As he puts it Elegy XXI: syphilis is the thing that is 'abominable' and enrages 'every fibre of my being'.

The suggestion that Goethe has been making his way to his assignations with his lover in the guise of priest as some kind of elaborate joke is absurd. Its only function is to introduce more invective about the hypocrisy and the corruption among the priestly hierarchy in Rome, specifically the Falconieri family, which was obliquely referenced in the anti-aristocratic Elegy III.

The response of Goethe's lover is a vehicle for exposing the Roman clergy as hypocritical fornicators and corrupters of the innocent. The phrase the 'red and the violet stockings' indicts all the upper levels of the Catholic Church in Rome, the Pope himself part of the widespread nepotism and corruption. In other words, this elegy may seem like a lovers' tiff, full of innigeres Gefühl, 'deep emotions', but it is in large measure one more broadside against the Catholic administration in Rome which Goethe so despised.

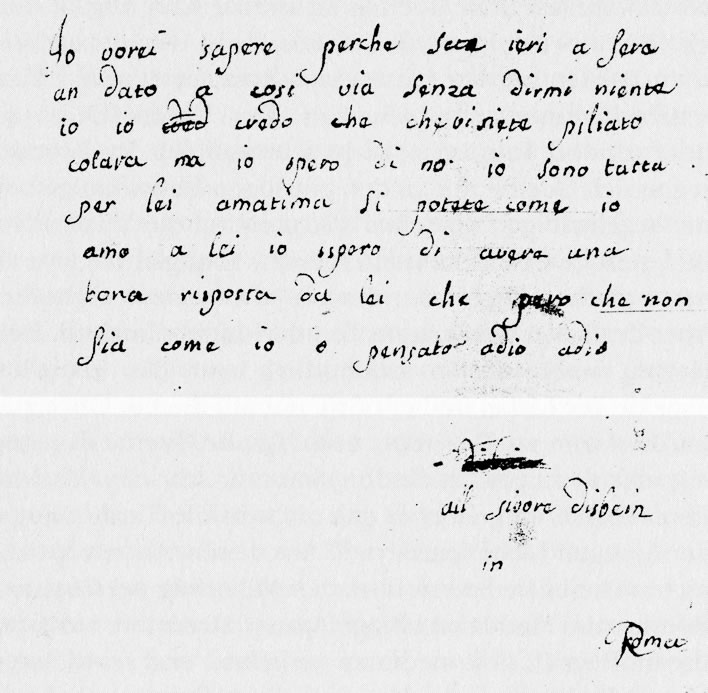

Roberto Zapperi made an interesting contribution to our understanding of this elegy in his book Das Inkognito. He discovered in G.'s effects a brief message in Italian sent to Goethe. For some reason it escaped the flames of G.'s destruction of many of the documents of his life, among them journals and papers from the time of his Italian journey. Perhaps the aged Goethe, sitting by the fire, just overlooked this scrap of paper from all those years ago in Rome, or perhaps he just could not bring himself to destroy the only surviving artefact of his Roman lover, written in her own hand.

The message is undated, but there can be no doubt that it derives from the time of G.'s stay in Rome and was written by his Beloved (whoever she may have been). We shall discuss the style of this message in the context of Elegy X, but in the present context, the interest is in what it says:

Front and back of a message to Goethe from his Italian beloved. Image: in Zapperi, 1999.

I would like to know why you left so abruptly yesterday evening, without saying anything to me. I fear that you are angry with me, but I hope not. I am all yours. Love me, if you could, just as I love you. I hope to receive a good answer from you, which, I hope, is not what I thought it is. Farewell, farewell.

Io vorei sapere perche sete ieri a sera an dato a cosi via senza dirmi niente io io credo che che vi siete piliato colara ma io spero di no io sono tutta per lei amatima si potete come io amo a lei io sspero di avere una bona risposta da lei che pero che non sia come io o pensato adio adio

Transcription Roberto Zapperi, Das Inkognito, 1999, p. 222.

Well, it would have been strange if there had been no tiffs in a four-month love affair. This one might indeed form the background to the present elegy, the clay, as it were, out of which G. kneaded his form.

We can easily imagine the distress of his lover: it was strong enough to drive her to write this message to him, despite the embarrassingly low level of her literacy. It is not a letter she could have asked a scribe to write for her, so in the emergency she had to put pen to paper herself.

Goethe's wordless departure is quite characteristic for him. Another female friend of his experienced it with full force, Barbara 'Babe' Schulthess. He had met her on several occasions, but passing through Constance on his way back from Italy to Weimar in early June 1788 they appear to have spent a very intense five or six days together in the Hotel Adler. Why else would the restless Goethe hang around in Constance for six days when Weimar and his Duke were awaiting him?

Let's put that date into context: in April 1788 he had left his Roman love in tears (he was quite teary, too, but poets can turn tears on and off like a tap); in June he was with Babe; in July he met Christiane Vulpius in Weimar.

Then, nearly ten years later in September 1797, en route to his third visit to the Gotthard, he called in again on Babe in Zurich. It seems she said something not to his liking and he cut her dead. No amount of pleading moved him. Most of Goethe's women met the same fate sooner or later.

So sometime in Rome, probably during the first quarter of 1788, his Italian lover said or did something and he simply exited without a word. Perhaps after a while the simplicity of her humble pleading softened his heart and/or his hormones started fizzing again – whatever. The main thing is, as all true poets do, he got a poem out of it all. And a cracker, at that.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!