Goethe's Römische Elegien XXI-XIV

Richard Law, UTC 2020-10-21 06:42

XXI Eines ist mir verdrießlich vor allen Dingen, ein andres [18]

Eines ist mir verdrießlich vor allen Dingen, ein andres

1Bleibt mir abscheulich, empört jegliche Faser in mir,

Nur der bloße Gedanke. Ich will es euch, Freunde, gestehen:

3Gar verdrießlich ist mir einsam das Lager zu Nacht.

Aber ganz abscheulich ists, auf dem Wege der Liebe

5Schlangen zu fürchten, und Gift unter den Rosen der Lust,

Wenn im schönsten Moment der hin sich gebenden Freude

7Deinem sinkenden Haupt lispelnde Sorge sich naht.

Darum macht Faustine mein Glück: sie teilet das Lager

9Gern mit mir, und bewahrt Treue dem Treuen genau.

Reizendes Hindernis will die rasche Jugend; ich liebe,

11Mich des versicherten Guts lange bequem zu erfreun.

Welche Seligkeit ists! wir wechseln sichere Küsse,

13Atem und Leben getrost saugen und flößen wir ein.

So erfreuen wir uns der langen Nächte, wir lauschen,

15Busen an Busen gedrängt, Stürmen und Regen und Guß.

Und so dämmert der Morgen heran; es bringen die Stunden

17Neue Blumen herbei, schmücken uns festlich den Tag.

Gönnet mir, o Quiriten! das Glück, und jedem gewähre

19Aller Güter der Welt erstes und letztes der Gott!

One thing I find more annoying than anything, there is also another thing that is abominable and every fibre of my being is enraged by …

… just the thought of it. I wish to confess, friends, that the annoying thing is the lonely bed at night.

The abominable thing is, on the way to love, having to fear serpents and fear poison among the roses of desire.

When just at the sweetest moment of surrender, lisping anxiety draws near your sinking head.

That is why Faustine makes me so happy: she shares my bed gladly and remains faithful to me, her faithful one.

The impetuous young find reticence alluring; I love in a way that I may enjoy long and comfortably the sure possession.

What bliss it is! we exchange safe kisses, confidently breathe in and breathe out air and life.

In this way we delight in the long nights, breast pressed on breast, we listen to storms, rain and downpours.

And thus the morning dawns; the hours bring new flowers, festively adorning the new day.

Allow me, O citizens of Rome, this happiness, and may the god grant to each one of you this first and last of all the world's delights.

Notes

Eines…ein andres…: Firstly, G. sets up two unnamed states which he finds intolerable in some way. One of them is verdrießlich, 'annoying', 'irritating'; the other is abscheulich, 'disgusting', 'revolting'. It is important for us to note that these two intolerables are not equal in intolerabilty: verdrießlich has nowhere near the tremendous force of abscheulich and the English translation reflects that.

Then G. goes on to put names to these intolerables: the merely annoying one is sleeping alone (that handy euphemism); the very annoying one is the ever present risk of catching syphilis. The latter weighs too heavily in this unequal contest. G.'s complex adjudication of the two states can be summed up very simply: so far he has put up with having to sleep alone because of the fear of contracting syphilis. Documentary research suggests that in the reality of G.'s time in Italy, the merely 'annoying' intolerability occasionally became so intolerable that he suppressed, at least for a night, his fear of the danger which he says revolted him.

Schlangen zu fürchten, und Gift unter den Rosen der Lust: 'serpents' and 'poison' are symbols that are familiar to us from Elegy XVII, which was self-censored and only published in 1914. The suppression of that powerful elegy inevitably weakens the impact of the present one.

In a letter from Rome to his Duke Carl August dated 29 December 1887 he described, as one philanderer to another, his problems with avoiding a lonely bed in Rome:

I hear from all sides that you are well, that you are enjoying yourself in the Hague and that the war horizon has brightened. The success with women that has neverl left you, will not desert you in Holland either and will compensate you for leaving the beautiful Emilia at home.

The sweet little god [Cupid] has relegated me to a grim corner of the world. The public girls of pleasure are as unsafe as everywhere else. The Zitellen (unmarried girls) are chaster than anywhere else, they will not be touched and ask immediately one becomes frisky with them: 'and how will it end?' Because either one has to marry them or they have to be married off to you and if they already have a husband, then the fat lady has sung. Yes, one can almost say that all eligible women are only available to those whom the family wishes to obtain. Those are all bad circumstances and the only chance of fun is with those who are as unsafe as public creatures. As far as the heart is concerned, it does not belong in the terminology of that department of love.

An den Herzog Carl August, Rom d. 29. Dec. 87.

Von allen Seiten höre ich daß es Ihnen wohl geht, daß Sie im Haag vergnügt sind und der Kriegshimmel sich aufgeheitert hat. Das Glück bey Frauen das Ihnen niemals gefehlt hat, wird Sie auch in Holland nicht verlassen und Sie dafür schadloß halten, daß Sie die schöne Emilie in Ihrem Hause versäumt haben.

Mich hat der süße kleine Gott in einen bösen Weltwinckel relegirt. Die öffentlichen Mädchen der Lust sind unsicher wie überall. Die Zitellen (unverheurathete Mädchen) sind keuscher als irgendwo, sie lassen sich nicht anrühren und fragen gleich, wenn man artig mit ihnen thut: e che concluderemo? Denn entweder man soll sie heurathen oder sie verheurathen und wenn sie einen Mann haben, dann ist die Messe gesungen. Ja man kann fast sagen, daß alle verheurathete Weiber dem zu Gebote stehn, der die Familie erhalten will. Das sind denn alles böse Bedingungen und zu naschen ist nur bey denen, die so unsicher sind als öffentliche Creaturen. Was das Herz betrifft; so gehört es gar nicht in die Terminologie der hiesigen Liebeskanzley.

Goethes Werke. Weimarer Ausgabe.

In G.'s letter to the feudal owner of his soul we find G. (then around 38 years old) pandering to his younger boss (then around 30 years old) with what can only be described as locker-room affectation. G. should really have grown out of this by now. A long thesis could be written on this theme, but it seems reasonable that having to mould himself into the feudal ways of the ducal court in Weimar was one of the major causes of the depression that struck him around 1785 and which triggered his abrupt departure for Italy. The Duke, like the rest of his ilk across Europe at the time, would hunt for fresh meat among the daughters of minor functionaries, landholders and peasants.

As it happens, shortly afterwards Duke Carl August, in his command as a Prussian General in an army camp in the Netherlands, rolled the syphilis dice once too often and was himself struck down by the serpent. On 6 April 1789 G. wrote to him from Weimar:

Let me know sometime how you are. I fear the miserable disease has not yet left you. I shall counter it in the most ignominious way with hexameters and pentameters, which will not help with the cure. Farewell and love me.

Sagen Sie mir gelegentlich ein Wort wie Sie Sich befinden. Ich fürchte das leidige Übel hat Sie noch nicht verlaßen. Ich werde ihm ehstens in Hexametern und Pentametern aufs schmählichste begegnen, das hilft aber nicht zur Cur. Leben Sie wohl und lieben mich.

Goethes Werke. Weimarer Ausgabe.

By this time, of course, G. was back from Italy and had settled down with the new, young occupant of his bed, Christiane Vulpius. He wrote once again to his ailing Duke in February 1790, deferentially, oily even, yet with a hint of smugness, outlining his own precautions:

If only a different misfortune kept you in Berlin! On that point I need to comfort myself less. Particularly because I feel so safe from this side. Unfortunately the precautions and modest contentment of your domestic counsel and poet, who rarely sleeps alone and still manages to keep his penis utterly pure, are unfitting for that of a military-political prince.

Wenn nur nicht ein ander Übel Sie in Berlin fest hielte! Darüber tröst ich mich weniger. Besonders da ich mich von dieser Seite so sicher fühle. Leider will sich die Vorsicht und Genügsamkeit Ihres häußlichen Rathes und Dichters, der selten allein schläft und doch penem purissimum erhält, nicht für die Lebensweise eines militarischen politischen Prinzen schicken.

Goethes Werke. Weimarer Ausgabe, IV. 51:89 (not online).

Faustine: As we have seen, G. took many precautions to cover his tracks during his stay in Italy and particularly any concerning his relationship with the young widowed mother of a young child in Rome.

We have already mentioned that this secrecy was not just due to G.'s longstanding habit of mystifying his readers, but also to the real possibility of serious sanctions were the affair to become public in Rome. It is therefore completely irrational to believe that the name he uses for his faithful lover in this elegy – and only in this elegy, nota bene – could even hint at the name of a real person.

In the 23 other elegies, G. has got by without once giving his beloved a name – why now? Catullus had his Lesbi a, Propertius his Cynthi a and Tibullus his Deli a, some cavaliers and anacreontic poets had their Celi as and Campaspes and Juli as. These poor girls didn't realise that these poets only loved them for their dactyls, and that they were there, insofar as they existed in the physical sense at all, in order to give posterity a hook on which to hang a poet's love poetry. But why didn't G. brand his object of desire? even if only with an alias?

Let's think radically. Perhaps it is because the Römische Elegien are not really about this woman, whoever she was. Of the 24 elegies, she appears directly in only 13. We are being generous: some of these 13 appearances are merely walk on parts or oblique references or so generic they could be anyone. There is clearly more going on in this collection of poems than a love affair.

In fact, all the elegies are really just about Goethe. He is the projection screen for this entire Roman experience. This is no surprise, since the tradition of the Augustan elegy, certainly as represented in the works of the 'triumvirate' – Tibullus, Propertius and Catullus – is that they more often than not represent the voice of the poet and the poet's personal experience (however distorted). Perhaps this is the one point where Goethe really departs from his models, so keen is he to distance himself from the action.

Would the use of a consistent name for the female in the Römische Elegien have created a female lead and have been a distraction from the hero/poet? G.'s lover is more of an accessory than the figure of a real woman; she is a cipher.

That said, it is as good as certain that the figure of Faustine is an amalgam of the real figures of the Roman widow and Christiane Vulpius, whom he met in Weimar in 1788, just at the time he began writing the Römische Elegien.

Without any evidence whatsoever, your author is nevertheless struck by the similarity between the name Faustine and G.'s epochal hero Faust. The suffix '-in(e)' is not a diminutive but a feminisation, that exists in some form in every Romanic language, English too, but especially in German. It is difficult to imagine that G. would have come up with this name without wishing to allude to the protagonist in his masterpiece.

The question is: of all the names upon which G. could have lit in order to provide him with an alias for his lover (whether Signora X and/or Christiane), why on earth should it be Faustine?

Is 'Faustine' the string puppet to G.'s Mephistopheles? Is she the novice passing through this extended rite of illumination, these coital mysteries? 'Do you now understand, Beloved, that wave?' (Elegy 14).

bewahrt Treue dem Treuen genau: 'faithful to me, her faithful one'. In the context of the possibility of infection, G. acknowledges how important sexual fidelity is to him – it is the only guarantee of freedom from infection with syphilis (or anything else of that nature). Given that we find this in the forefront of his mind, we can now understand the paranoia that drove him to question the fidelity of his loved one in Elegy VIII.

Atem und Leben getrost saugen und flößen wir ein: Atem, 'breath' and its cognates in many languages (πνεῦμα) have been frequently used to refer to spirit, soul and indeed life itself; a spirit that is sucked in and exhaled in the kisses of the lovers.

wir lauschen, Busen an Busen gedrängt, Stürmen und Regen und Guß.: 'breast pressed on breast, we listen to storms, rain and downpour'. G. is alluding directly to a passage from Tibullus 1.1:46-48, a passage which we also referenced in more general sense in Elegy XI:

How delightful to hear the raging gales from the bedroom whilst holding my love in my gentle arms or, when a wintry south wind throws down its icy rain, to seek, aided by the fire, a carefree sleep.

Quam iuvat inmites ventos audire cubantem / Et dominam tenero continuisse sinu / Aut, gelidas hibernus aquas cum fuderit Auster, / Securum somnos igne iuvante sequi.

Tibullus 1.1. This autumn/winter scene is a counterweight to the mention of the blazing heat of the dog-days of summer a few lines before (27-28).

es bringen die Stunden Neue Blumen herbei: die Stunden can be taken simply as the hours, but it seems certain that G. was implying die Horen here, the mythological 'Horae', the 'Hours', the goddesses of time and the seasons, who as dawn breaks after a night of rain 'bring the new flowers'. Die Horen was, of course, also the title of Schiller's literary magazine in which the twenty Römische Elegien first appeared together.

Quiriten: the citizens of Rome.

jedem gewähre…der Gott!: this passage brings German grammar to its knees. G.'s manuscript version of this distich made things a little easier for the reader: Gönnet mir Quiriten dies Glück und welcher mich tadelt / Werde glücklich wie ich, fühle es and lobe mich dann. 'Allow me citizens of Rome this happiness and may those who criticise become as happy as I am, feel that [happiness], and praise me then'.

Commentary

Of the twenty elegies that were not proactively suppressed, it was this elegy that gave contemporaries the most concern. It is not difficult to see why, hovering as the poem does between the horrors of syphilis and the pleasures of faithful but extramarital sex.

It is also the elegy in which the figures of Goethe's Roman and Weimar loves are blended together so inseparably: instead of Goethe's appeal in the last distich to the 'citizens of Rome' for understanding, we could just as easily substitute the 'citizens of Weimar', many of whom objected to their recently ennobled resident genius being openly shacked up with a girl from the lower orders – Goethe's Ehe ohne Zeremonie, 'marriage without a ceremony', would persist for 18 years, until he finally married Christiane in 1806.

XXII Schwer erhalten wir uns den guten Namen, denn Fama [19]

Schwer erhalten wir uns den guten Namen, denn Fama

1Steht mit Amorn, ich weiß, meinem Gebieter, in Streit.

Wißt ihr auch, woher es entsprang, daß beide sich hassen?

3Alte Geschichten sind das, und ich erzähle sie wohl.

Immer die mächtige Göttin, doch war sie für die Gesellschaft

5Unerträglich, denn gern führt sie das herrschende Wort;

Und so war sie von je, bei allen Göttergelagen,

7Mit der Stimme von Erz, Großen und Kleinen verhaßt.

So berühmte sie einst sich übermütig, sie habe

9Jovis herrlichen Sohn ganz sich zum Sklaven gemacht.

„Meinen Herkules führ ich dereinst, o Vater der Götter”,

11Rief triumphierend sie aus, „wiedergeboren dir zu.

Herkules ist es nicht mehr, den dir Alkmene geboren:

13Seine Verehrung für mich macht ihn auf Erden zum Gott.

Schaut er nach dem Olymp, so glaubst du, er schaue nach deinen

15Mächtigen Knieen — vergib! nur in den Äther nach mir

Blickt der würdigste Mann, nur mich zu verdienen, durchschreitet

17Leicht sein mächtiger Fuß Bahnen, die keiner betrat;

Aber auch ich begegn ihm auf seinen Wegen und preise

19Seinen Namen voraus, eh er die Tat noch beginnt.

Mich vermählst du ihm einst: der Amazonen Besieger

21Werd auch meiner, und ihn nenn ich mit Freuden Gemahl!”

Alles schwieg; sie mochten nicht gern die Prahlerin reizen:

23Denn sie denkt sich, erzürnt, leicht was Gehässiges aus.

Amorn bemerkte sie nicht: er schlich beiseite; den Helden

25Bracht er mit weniger Kunst unter der Schönsten Gewalt.

Nun vermummt er sein Paar: ihr hängt er die Bürde des Löwen

27Über die Schultern und lehnt mühsam die Keule dazu,

Drauf bespickt er mit Blumen des Helden sträubende Haare,

29Reichet den Rocken der Faust, die sich dem Scherze bequemt.

So vollendet er bald die neckische Gruppe; dann läuft er,

31Ruft durch den ganzen Olymp: „Herrliche Taten geschehn!

Nie hat Erd und Himmel, die unermüdete Sonne

33Hat auf der ewigen Bahn keines der Wunder erblickt.”

Alles eilte: sie glaubten dem losen Knaben, denn ernstlich

35Hatt er gesprochen; und auch Fama, sie blieb nicht zurück.

Wer sich freute, den Mann so tief erniedrigt zu sehen,

37Denkt ihr? Juno. Es galt Amorn ein freundlich Gesicht.

Fama daneben, wie stand sie beschämt, verlegen, verzweifelnd!

39Anfangs lachte sie nur: „Masken, ihr Götter, sind das!

Meinen Helden, ich kenn ihn zu gut! Es haben Tragöden

41Uns zum besten!” Doch bald sah sie mit Schmerzen: er wars! —

Nicht den tausendsten Teil verdroß es Vulkanen, sein Weibchen

43Mit dem rüstigen Freund unter den Maschen zu sehn,

Als das verständige Netz im rechten Moment sie umfaßte,

45Rasch die Verschlungnen umschlang, fest die Genießenden hielt.

Wie sich die Jünglinge freuten, Merkur und Bacchus! sie beide

47Mußten gestehn: es sei, über dem Busen zu ruhn

Dieses herrlichen Weibes, ein schöner Gedanke. Sie baten:

49Löse, Vulkan, sie noch nicht! Laß sie noch einmal besehn!

Und der Alte war so Hahnrei, und hielt sie nur fester. —

51Aber Fama, sie floh rasch und voll Grimmes davon.

Seit der Zeit ist zwischen den Zweien der Fehde nicht Stillstand:

53Wie sie sich Helden erwählt, gleich ist der Knabe danach.

Wer sie am höchsten verehrt, den weiß er am besten zu fassen,

55Und den Sittlichsten greift er am gefährlichsten an.

Will ihm einer entgehn, den bringt er vom Schlimmen ins Schlimmste.

57Mädchen bietet er an: wer sie ihm töricht verschmäht,

Muß erst grimmige Pfeile von seinem Bogen erdulden;

59Mann erhitzt er auf Mann, treibt die Begierden aufs Tier,

Wer sich seiner schämt, der muß erst leiden; dem Heuchler

61Streut er bittern Genuß unter Verbrechen und Not.

Aber auch sie, die Göttin, verfolgt ihn mit Augen und Ohren:

63Sieht sie ihn einmal bei dir, gleich ist sie feindlich gesinnt,

Schreckt dich mit ernstem Blick, verachtenden Mienen, und heftig

65Strenge verruft sie das Haus, das er gewöhnlich besucht.

Und so geht es auch mir: schon leid ich ein wenig; die Göttin,

67Eifersüchtig, sie forscht meinem Geheimnisse nach.

Doch es ist ein altes Gesetz: ich schweig und verehre:

69Denn der Könige Zwist büßten die Griechen wie ich.

It is difficult to keep our good name, for the goddess Reputation feuds with Cupid, my master.

Do you know how it came to pass that they hate each other? Those are old stories and I retell them happily.

Always the powerful goddess, but she was unbearable for the godly community, for she happily claimed the last word;

And so at every banquet she was always there with her bronze voice, hated by great and small.

So she once boasted arrogantly that she had made Jove's magnificent son her slave.

'One day, O Father of the Gods', she called out triumphantly, 'I shall bring my Hercules reborn to you.

Hercules is no longer the son Alcmene bore you: his worship of me makes him on earth a god.

When he looks towards Olympus you believe his is looking at your powerful knees – forgive me! only in the air towards me

Is the most worthy man looking, only to earn me, his mighty foot lightly took ways, which no other took;

But also I meet him on the way to his deeds and praise his name in advance, before the labour has even begun.

One day you will marry him to me: the conqueror of the Amazons will be mine and I shall call him husband with pleasure!'

Everyone was silent; they did not want to rile the braggart: for in rage she could easily think of something malicious.

She did not notice Cupid: he crept quietly away; he brought the hero Hercules easily under the power of the most beautiful one.

Now he dressed up his couple: he hung the skin of the lion over her shoulders as a mantle and with difficulty leaned the club against her,

He studded the hero's bristly hair with flowers, put a distaff in his fist, completing the joke.

And so he completed the teasing group; the he ran through all of Olympus, calling: 'A wonderful deed has occurred!

Never has Earth and Heaven, the tireless Sun on its eternal journey, have never seen such a miracle!'

Everyone rushed to see: the believed the mischievous boy, who had spoken so gravely; and even the goddess Reputation was not left behind.

Who do you think was happiest to see the mortal so humiliated? Juno. Cupid received a friendly glance.

Reputation to one side, how she stood, ashamed, emabarrassed, despairing!

At first she just laughed: 'Those are mere masks, you gods!'

My hero, I know him too well! Actors are trying to trick us!' But soon she saw with pain: it was him! –

Vulcan had not been a thousandth so displeased to see his woman caught under the mesh with his vigorous friend,

When the clever net wrapped around them at just the right moment, quickly entwining the entwined, holding the enjoyers fast.

How the lads laughed, Mercury and Bacchus! they had to admit that the thought of resting on the bosom

Of this wonderful woman was a beautiful thought. They asked: do not release them yet, Vulcan! Let them be seen once more!

And the old one was so cuckolded that he held them even tighter. — But Reputation fled away quickly, full of anger.

Since that moment the feud has not stood still: when she makes a hero, Cupid is right behind.

Whoever worships her the most, he knows how best to catch them, and to the most respectable he is the most dangerous.

Whoever tries to escape him, he brings from bad to worse. He offers girls: whoever stupidly despises him,

Has to endure the awful arrows from his bow; he stokes the desire of man for man, drives lust to bestiality,

Whoever feels shame, has to first suffer; for the hypocrite he spreads bitter tastes amongst crime and hardship.

But also she, the goddess [Reputation] follows him [Cupid] with eyes and ears: should she see him near to you her emnity is immediate,

Frightens you with severe looks, contemptuous expressions and she condemns the house which he [Cupid] regularly visits.

And so it is for me: already I am suffering a little; the goddess [Reputation], jealous, searches out my secrets.

But it is an old law: I stay silent and worship: for the Greeks had to suffer for the discord of the kings just as I do.

Notes

Fama: The goddess of rumour and reputation. The traditional, glib translation of her Latin name into the English 'Fame' is extremely misleading: she has no good properties. Probably 'Rumour' is the best simple equivalence. The source of G.'s understanding of the goddess is Ovid's Metamorphoses:

There is a spot convenient in the center of the world, between the land and sea and the wide heavens, the meeting of the threefold universe. From there is seen all things that anywhere exist, although in distant regions far; and there all sounds of earth and space are heard.

Fame is possessor of this chosen place, and has her habitation in a tower, which aids her view from that exalted highs. And she has fixed there numerous avenues, and openings, a thousand, to her tower and no gates with closed entrance, for the house is open, night and day, of sounding brass, echoing the tones of every voice. It must repeat whatever it may hear; and there's no rest, and silence in no part. There is no clamour; but the murmuring sound of subdued voices, such as may arise from waves of a far sea, which one may hear who listens at a distance; or the sound which ends a thunderclap, when Jupiter has clashed black clouds together. Fickle crowds are always in that hall, that come and go, and myriad rumours — false tales mixed with true — are circulated in confusing words. Some fill their empty ears with all this talk, and some spread elsewhere all that's told to them. The volume of wild fiction grows apace, and each narrator adds to what he hears.

Credulity is there and rash Mistake, and empty Joy, and coward Fear alarmed by quick Sedition, and soft Whisper—all of doubtful life. Fame sees what things are done in heaven and on the sea, and on the earth. She spies all things in the wide universe.

P. Ovidius Naso, Metamorphoses, Brookes More, Ed., 12.39-63. The Latin original is also available at this link.

In this context the translation of Fama as 'Fame' is even more inappropriate, because G. emphasises the corollary of Rumour, that is, reputation; for it is rumour that builds or destroys good reputation.

Steht mit Amorn…in Streit: As discussed more fully in the commentary, G. is writing his own mythology here, which turns out to be a symbolic treatment of the difficulty of maintaining a good reputation whilst experiencing the lust-filled mania the slaves to Cupid must suffer – hence the mythological duality.

die mächtige Göttin: The powerful goddess Fama/Rumour.

Mit der Stimme von Erz: A direct allusion to Metamorphoses 12: for the house is open, night and day, of sounding brass, echoing the tones of every voice.

Jovis herrlichen Sohn: 'Jove's magnificent son', that is Hercules.

Alkmene: The mother of Hercules.

Seine Verehrung für mich macht ihn auf Erden zum Gott: In recognition of the divinity of his father as well as the nobility of the many, ostensibly impossible deeds he performed, he became a divinity in his own right. G. is overlaying the mythological tradition of Hercules joining the gods on Olympus as a result of his heroic deeds with the goddess Reputation's suggestion that Hercules was doing this for his own vainglory, which had in turn made him a god to the mortals on earth.

Mächtigen Knieen: From Homeric times onwards (and in many Near Eastern and Mediterranean cultures in addition to the Greeks and Romans), mortals did not stand eye-to-eye with gods. The knees of the god were the highest point mortals could revere, the highest point to which they dare lift their reverent gaze.

Bahnen, die keiner betrat: Alluding to the twelve labours of Hercules.

der Amazonen Besieger: Alluding to the ninth labour of Hercules, in which Hercules was sent to rob Hippolyta, the Queen of the Amazons, of her girdle. A central point of that story, of particular relevance in the present context, comes when the goddess Hera/Juno, no fan of Hercules, who had been conceived by a union of Jupiter, her husband, and Alcmene, caused the Amazons to rise up against him by circulating a rumour about him to the effect that he was about to abduct their queen. Hercules, as usual, slew everyone in sight and took the girdle.

den Helden…Bracht er mit weniger Kunst unter der Schönsten Gewalt: Tired of Fama's boastfulness, Cupid demonstrated his superior powers by causing Fama's protégé Hercules to fall passionately in love with the beautiful Omphalus. Once the mania had overcome Hercules, 'had brought him with little effort under the power of the most beautiful one', he made him look foolish in his doting. The tale of Cupid's trickery is to be found in several sources, but principally Ovid, Fasti, 2.303-62. It is also alluded to in Propertius 3.11:17-20 and 4.9.45-50.

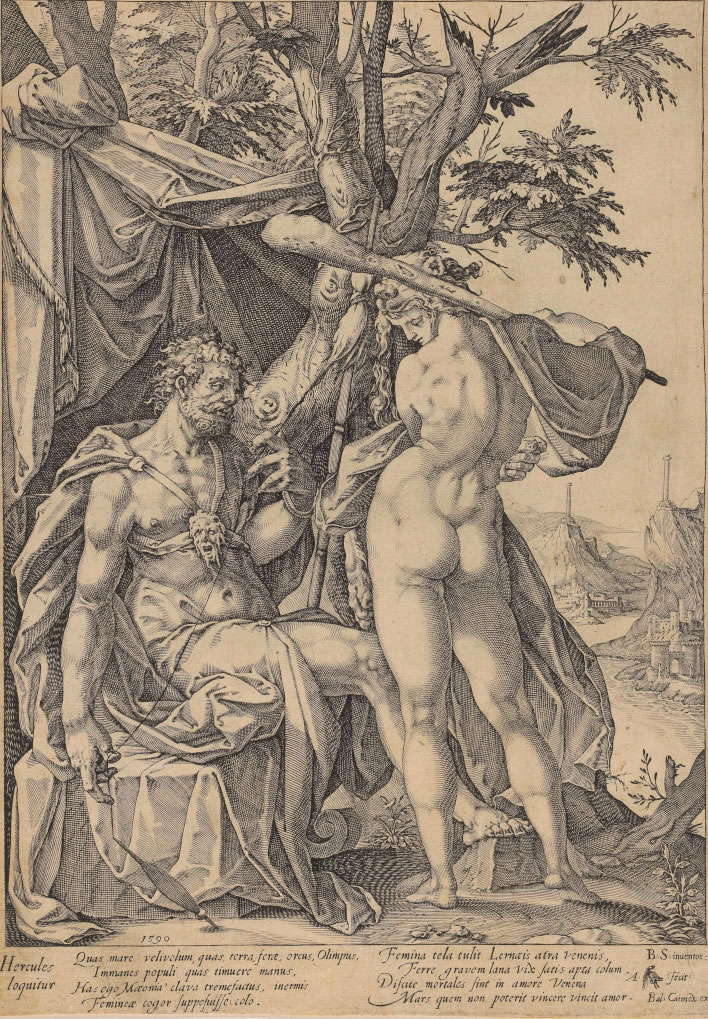

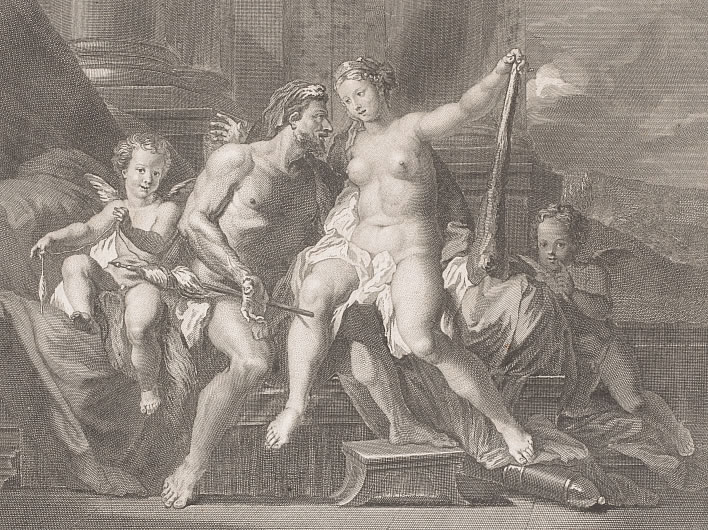

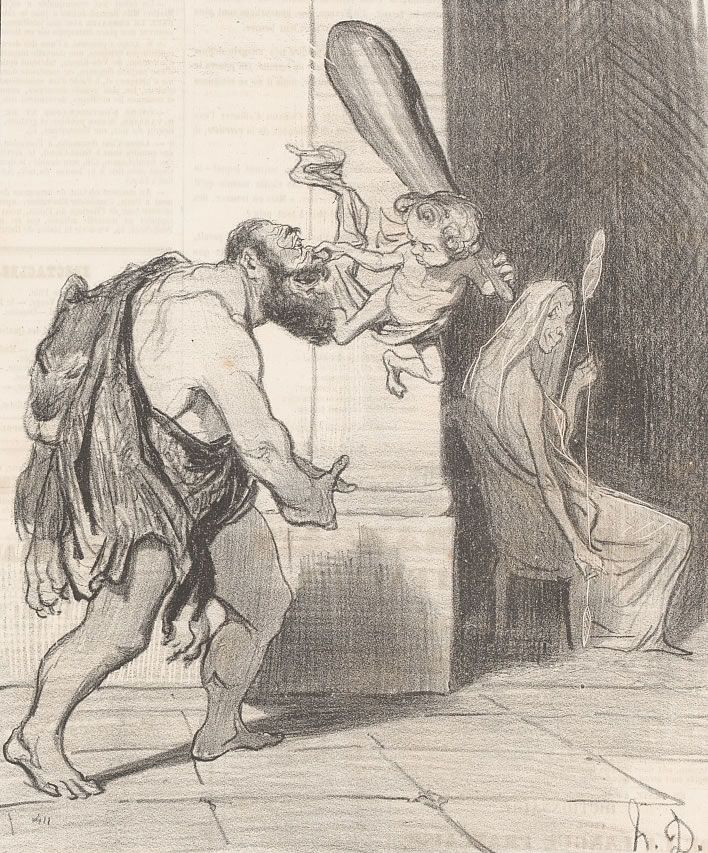

Although G. has invented the wider context of the direct contest between Fama and Cupid, the story of the humiliation of Hercules in his passion for a woman was a traditional one and G.'s description of the scene follows the classical model. The sight of the once great hero now feminised into domestic docility became a popular one with visual artists from the time of the Renaissance onwards, as a quick, unrepresentative dip into the collection of the excellent Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands shows:

die Bürde des Löwen: The word Bürde is obsolete now except for its sense of 'burden', 'weight'. G. is using the word in its old sense of was vom menschen auf arm, schulter, hals, kopf und rücken getragen wird [DWB] 'something that is worn by people on the arm, shoulder, throat, head and back'. Your translator has decided that Omphale, clearly making a fashion statement, is wearing the skin of the lion as a 'mantle', which is how the illustrators here represent it.

A beautifully executed, detail-perfect representation of the feminised domesticity: Cupid hovering above the scene, in total control – he is the true master here; Hercules, in his new hairdo, concentrating devotedly on his spinning, his foot resting on his club; Omphale, crowned with the head of the lion's skin, holding Hercules under her control, looking at the viewer with an expression of triumph; the other figures appear to be female servants.

Hercules and Omphale, Aegidius Sadeler (engraver), Bartholomeus Spranger (artist), 1580-1629. Image: Rijksmuseum. [Click to view a larger image in a new tab.]

A rather mannered, humourless representation of Hercules spinning whilst Omphalus wears the lion head and holds his club. Cupid is absent.

Hercules and Omphale, Anton Eisenhoit (engraver), Bartholomeus Spranger (artist), 1590. Image: Rijksmuseum. [Click to view a larger image in a new tab.]

A wonderfully humorous representation of the pansified Hercules, with curly hair and moustache, decorative cap and wearing a flouncy dress showing off his new nipples; Omphale is wearing the lion's head and looking triumphantly happy. We can forgive the absence of the club and of Cupid, who brought this all about. Any resemblance to current ex-members of the British royal family is completely fortuitous.

Hercules and Omphale, Bartholomeus Willemsz (engraver), Bartholomeus Spranger (artist), 1589-1626. Image: Rijksmuseum. [Click to view a larger image in a new tab.]

Hercules, leaning devotedly towards Omphale, hair and beard curled and bowed, busy at his spinning. She is not wearing the lion's head, but the symbols of Hercules' former life as a hero are at her side: the bow, the lion's skin and the club; the composition places her figure between the feminised hero and the artefacts of his former manly life. At least one Cupid, arrow at the ready and a watching boy without particular attributes.

Hercules and Omphale, Michel Dorigny (engraver), Simon Vouet (artist), 1643. Image: Rijksmuseum. [Click to view a larger image in a new tab.]

A good representation of Hercules' passion for Omphale, including two Cupids for good measure. Omphale has the hero's club well under control, but a lack of specifics from the mythological source.

Hercules and Omphale, Nicolas de Larmessin (engraver), 1694-1755. Image: Rijksmuseum. [Click to view a larger image in a new tab.]

Omphale wearing the lion's head cap, holding the club with Cupid in attendance; Hercules, though curly-headed, is not spinning but playing the tambourine. His face and his situation reminds your author of someone… but who?

Hercules and Omphale, Pietro Bettelini (engraver), Annibale Carracci (artist), 1773-1829. Image: Rijksmuseum. [Click to view a larger image in a new tab.]

A wonderful, left-field caricature by the master of such things, Honoré Daumier. Hercules, cloaked in the lion's skin, is being led by the nose by Cupid, who is holding the massive club of the hero with total dominance. The French title Hercule dompté par l'Amour is difficult to translate well, since there is no easy equivalent for dompté, 'being trained' in the sense that the performing animal in the circus is trained by the dompteur. Omphalus, Hercules' future, is waiting around the corner with a smile on her face, spinning equipment at the ready.

Hercules being trained by Cupid, Honoré Daumier, 1842. Image: Rijksmuseum. [Click to view a larger image in a new tab.]

Tibullus put the case from the point of the duped one:

I care nothing for reputation, my Delia; only let me be with you, and it won't matter if people call me slow and incompetent.

Non ego laudari curo, mea Delia; tecum / Dum modo sim, quaeso segnis inersque vocer.

Tibullus 1.1:57-58.

Over to you, Dr. Freud.

Wer sich freute…Juno: Hercules was the offspring of a coupling between Jupiter and Alkmene. Thus Juno, Jupiter's 'wife', particularly enjoyed Hercules' humiliation.

Masken, ihr Götter, sind das: The actors in Greek drama wore masks to indicate the persona of the characters they were playing. Here, G. is using 'mask' metonymically for the actor behind it.

Vulkanen, sein Weibchen…dem rüstigen Freund: Vulcan (GK. Hephaestus) was the son of Jupiter and Juno. He was the blacksmith god of fire and metalworking; his wife (Weibchen) was Venus (Gk. Aphrodite) and his rüstigen Freund, 'hearty friend', was Mars (Gk. Ares). The Odyssey, 8:266-366, is the principal source for the tale (a passage which G. himself translated):

Now to his harp the blinded minstrel sang

of Ares' dalliance with Aphrodite:

how hidden in Hephaistos' house they played

at love together, and the gifts of Ares,

dishonoring Hephaistos' bed — and how

the word that wounds the heart came to the master

from Helios, who had seen the two embrace;

and when he learned it, Lord Hephaistos went

with baleful calculation to his forge.

There mightily he armed his anvil block

and hammered out a chain, whose tempered links

could not be sprung or bent; he meant that they should hold.

Those shackles fashioned, hot in wrath Hephaistos

climbed to the bower and the bed of love,

pooled all his net of chain around the bed posts

and swung it from the rafters overhead –

light as a cobweb even gods in bliss

could not perceive, so wonderful his cunning.Seeing his bed now made a snare, he feigned

a journey to the trim stronghold of Lemnos,

the dearest of earth's towns to him. And Ares?

Ah, golden Ares' watch had its reward

when he beheld the great smith leaving home.

How promptly to the famous door he came,

intent on pleasure with sweet Kythereia!

She, who had left her father's side but now,

sat in her chamber when her lover entered;

and tenderly he pressed her hand and said:

'Come and lie down, my darling, and be happy!

Hephaistos is no longer here, but gone

to see his grunting Sintian friends on Lemnos.'As she, too, thought repose would be most welcome,

the pair went in to bed — into a shower

of clever chains, the netting of Hephaistos.

So trussed, they could not move apart, nor rise,

at last they knew there could be no escape,

they were to see the glorious cripple now —

for Helios had spied for him, and told him;

so he turned back, this side of Lemnos Isle,

sick at heart, making his way homeward.Now in the doorway of the room he stood

while deadly rage took hold of him; his voice,

hoarse and terrible, reached all the gods:

'O Father Zeus, O gods in bliss forever,

here is indecorous entertainment for you,

Aphrodite, Zeus's daughter,

caught in the act, cheating me, her cripple,

with Ares — devastating Ares.

Cleanlimbed beauty is her joy, not these

bandylegs I came into the world with:

no one to blame but the two gods who bred me!

Come see this pair entwining here

in my own bed! How hot it makes me burn!

I think they may not care to lie much longer,

pressing on one another, passionate lovers;

they'll have enough of bed together soon.

And yet the chain that bagged them holds them down

till Father sends me back my wedding gifts-

all that I poured out for his damned pigeon,

so lovely, and so wanton.'All the others were crowding in, now, to the brazen house —

Poseidon who embraces earth, and Hermes

the runner, and Apollo, lord of Distance.

The goddesses stayed home for shame; but these

munificences ranged there in the doorway,

and irrepressible among them all

arose the laughter of the happy gods.

The Odyssey, translated by Robert Fitzgerald, Doubleday, 1961

Mars and Venus caught in the act. We recall our note on the utility of seidne Gehäng, silken hangings, around a bed in The armour dropped on the floor is always a hint that something is going on.

Joachim Anthonisz. Wtewael, Mars and Venus Surprised by Vulcan, 1604-1608. Image: J. Paul Getty Museum. [Click to show a larger image in a new browser tab.]

die Jünglinge: In the original Homeric telling, it is Mercury and Apollo who, whilst observing Venus in her entrapment, have a laddish conversation about whether they would sleep with her. G. has changed this to a conversation between Mercury and Bacchus.

They made these improving remarks to one another,

but Apollo leaned aside to say to Hermes:

'Son of Zeus, beneficent Wayfinder,

would you accept a coverlet of chain, if only

you lay by Aphrodite's golden side?'

To this the Wayfinder replied, shining:

'Would I not, though, Apollo of distances!

Wrap me in chains three times the weight of these,

come goddesses and gods to see the fun;

only let me lie beside the pale-golden one!'

The Odyssey, translated by Robert Fitzgerald, Doubleday, 1961

über dem Busen zu ruhn: In the manuscript version of this elegy our poet calls a spade a spade: zwischen den Schenkel zu ruhn, 'to rest between her thighs' – clearly a step too far for his readers.

Mann erhitzt er auf Mann, treibt die Begierden aufs Tier: Cupid can drive men to homosexuality and to bestiality.

sie, die Göttin: The goddess Fama, Reputation.

verruft sie das Haus, das er gewöhnlich besucht: We recall G.'s lover telling him of the scandal his visits to her were beginning to cause in Elegy VIII.

der Könige Zwist büßten die Griechen wie ich: The phrase is an allusion to Horace, Epistles, 1.2:14: quidquid delirant reges, plectuntur Achivi, 'whatever enrages the kings, the Greeks must suffer it'. For G., the rage of the two kings here denotes the wild animosity between the goddess Fama and the god Cupid. G. is a worshipper of Cupid and so must bear the assaults on his reputation by the goddess.

Commentary

This elegy is a mix of traditional mythological elements in a framework of Goethe's own fabrications. For example, the scene in which the gods are gathered on Olympus listening to the goddess Fama's boasting is Goethe's invention, but it leads into the ancient tale of the passion of Hercules for Omphale. Then the ancient tale of the mockery of the gods at the discomfort of Mars and Venus, caught by Vulcan in flagrante is also woven into the Omphale story.

Although we distinguish between authentic mythological elements – that is, elements found in classical authors – and Goethe's own inventions, we have to accept that there is no ontological difference between them. The author(s) of the Homeric Epics, or Thesiod or Ovid et. al. made up and/or embellished these tales for dramatic or didactic purposes – just as Goethe has done with his own tale in this elegy. It is what artists do and always have done. In effect, Goethe, in writing his own mythological tale, is only imitating what his classical models had done.

This elegy is ultimately a metaphorical reworking of a problem which faced him during his time in Rome and which became much more urgent after he returned to Weimar and began to write his Römische Elegien. As we have already noted on several occasions, in Rome, Goethe had to exercise extreme caution. During his presence in Italy he was, with very few exceptions, incognito. It is doubtful whether even his lover knew his real name; he, of course, went to extreme lengths to hide her identity. These precautions shielded him from the wrath of the goddess Reputation at his worship at Cupid's altar.

Once he returned to Weimar, the benefits of the careful incognito disappeared. Very soon after he returned he met the young Christiane Vulpius. The pair hit it off very quickly and she moved in with Goethe, who has already informed us of his dislike of lonely beds (in Elegy XXI). The outrage in this small city over Goethe's open flaunting of all the sexual norms of his time was considerable. When the initial dalliance with Christiane stretched out over nearly twenty years and five illegitimate children came (and four went in infancy), scandal and gossip was unavoidable. Christiane was excluded from all social interactions with the court and despite her husband's eminence, she remained in her own petit bourgeois world.

Goethe always enjoyed the backing of his Duke: Carl August never forgot that he had a sage of world format in his tiny dukedom, which fact put its name and by association his name on the lips of the educated throughout Europe. Nor could the Duke, himself an epic fornicator in accordance with his station, hardly side with the uptight prodnoses and the gossips of his court – that would have been just too hypocritical.

But even with this powerful backing, Goethe had to endure much snide obloquy in word and deed. The court in Weimar – probably as courts everywhere in every age – was a hive of busy intriguers, backstabbers, the spiteful and the ambitious. This elegy is a metaphorical treatment of his situation and we are justified in seeing Weimar as a modern Olympus, peopled by courtiers happy to mock the discomfiture of the careless lover, the servant of Cupid and his mistress.

The coda to this elegy comes in 1823, around thirty years after it was written, when its author was 73. In Marienbad in the summer of 1821 he had got to know the 17 year-old Ulrike von Levetzow (1804-1899). They encountered each other a few times on the spa circuit, until in 1823, Cupid loosed one of his particularly malignant arrows, causing the ancient Goethe to spring a proposal of marriage on her.

The poor girl herself had only the vaguest idea who this elderly gentleman, three times her age, was. Like Christiane Vulpius, she was no aesthete or cultivated mind. Her family and everyone else involved were so stunned that no one really knew how to react to Goethe's offer. They stalled for time. Goethe interpreted the delay correctly and withdrew his offer, before he made himself look a bigger fool than Hercules with Omphale.

But that's alright – he's a poet, and so he got some poems out of it, which is the main thing: the principal one being the Marienbader Elegie. Some consider it as being among Goethe's greatest poems, some as among his worst; it is certainly not an 'elegy' in any sense that we would recognise, but that in itself shows how far the poet has come since those heady days with Christiane in Weimar.

XXIII Zieret Stärke den Mann und freies mutiges Wesen [20]

Zieret Stärke den Mann und freies mutiges Wesen,

1O! so ziemet ihm fast tiefes Geheimnis noch mehr.

Städtebezwingerin du, Verschwiegenheit! Fürstin der Völker!

3Teure Göttin, die mich sicher durchs Leben geführt,

Welches Schicksal erfahr ich! Es löset scherzend die Muse,

5Amor löset, der Schalk, mir den verschlossenen Mund.

Ach, schon wird es so schwer, der Könige Schande verbergen!

7Weder die Krone bedeckt, weder ein phrygischer Bund

Midas verlängertes Ohr: der nächste Diener entdeckt es,

9Und ihm ängstet und drückt gleich das Geheimnis die Brust,

In die Erde vergrüb er es gern, um sich zu erleichtern;

11Doch die Erde verwahrt solche Geheimnisse nicht,

Rohre sprießen hervor und rauschen und lispeln im Winde:

13Midas! Midas, der Fürst trägt ein verlängertes Ohr!

Schwerer wird es nun mir, ein schönes Geheimnis zu wahren,

15Ach, den Lippen entquillt Fülle des Herzens so leicht!

Keiner Freundin darfs ich vertraun: sie möchte mich schelten;

17Keinem Freunde: vielleicht brächte der Freund mir Gefahr.

Mein Entzücken dem Hain, den schallenden Felsen zu sagen,

19Bin ich endlich nicht jung, bin ich nicht einsam genug.

Dir, Hexameter, dir, Pentameter, sei es vertrauet,

21Wie sie des Tags mich erfreut, wie sie des Nachts mich beglückt.

Sie, von vielen Männern gesucht, vermeidet die Schlingen,

23Die ihr der Kühnere frech, heimlich der Listige legt;

Klug und zierlich schlüpft sie vorbei und kennet die Wege,

25Wo sie der Liebste gewiß lauschend begierig empfängt.

Zaudre, Luna, sie kommt! damit sie der Nachbar nicht sehe;

27Rausche, Lüftchen, im Laub! niemand vernehme den Tritt.

Und ihr, wachset und blüht, geliebte Lieder, und wieget

29Euch im leisesten Hauch lauer und liebender Luft,

Und entdeckt den Quiriten, wie jene Rohre geschwätzig,

31Eines glücklichen Paars schönes Geheimnis zuletzt.

Though strength and a free and courageous nature adorn a man, O! deep secrecy perhaps becomes him even more.

You conqueror of cities, Discretion! you ruler of peoples! Beloved goddess, who has led me safely through life,

What a fate is now mine! Jestingly the Muse [loosens my tongue] unlocks my closed mouth, as too does Cupid, the rogue.

Alas, it has already become so difficult to hide the shame of kings! Neither the crown nor a Phrygian bonnet

Can cover Midas' elongated ears: his closest servant discovers it, and the secret fills him with fear and weighs on his breast,

He would bury it in the ground, to find relief, but the earth will not keep such secrets,

Reeds spring up and rustle and lisp into the wind: Midas! Midas the king, has lengthened ears!

It is even harder for me to keep a sweet secret, the fullness of the heart gushes out through the lips so easily!

I can confide it to no female friend, she might scold me; to no male friend: for he might become a dangerous rival.

I am no longer young enough or solitary enough to confide my joy to the grove or to the echoing crag.

But in you, Hexameter, in you, Pentameter, I shall confide it, how she gladdens my by day and blesses me at night.

She, sought after by many men, avoids the snares that are laid insolently by the bold and furtively by the cunning.

Cleverly and daintily she slips past them and knows the roads where the beloved, listening eagerly, will receive her passionately.

Delay, Moon, she is coming! so that the neighbour will not see her; rustle, breezes, in the leaves! so that no one will hear her footfall.

And you, my beloved songs, grow and blossom and rock yourselves gently in the softest breath of warm and loving air,

and reveal at last to the citizens of Rome, as did once those chattering reeds, the sweet secret of a happy pair of lovers.

Notes

Verschwiegenheit: G. invents his own allegorical goddess, Discretion, who could be considered to be the polar opposite of the goddess Fama, 'Reputation' in the previous elegy, Elegy XXII.

die Muse…Amor: G.'s new goddess Discretion is the counterpart of the other two gods in the poet's life, the Muses and Cupid.

der Könige Schande: The following section of the elegy is based on the tale of Midas, the king of Phrygia, as it is recounted in Book 11 of Ovid's Metamorphoses. Here is the executive summary:

The shepherd god Tmolus was judging a musical contest between the god Apollo and the minor deity Pan. Tmolus wisely choose Apollo as the winner. All those present – wisely – agreed, except the Phrygian king Midas, who objected to the verdict. As a punishment for such lese-majesty Apollo caused his musically-defective ears to elongate and become hairy until they resembled the ears of a 'slow-moving ass'. Midas attempted to cover the disfigurement with a purple turban, a tiara, 'the head-dress of orientals'. Thanks to Midas, a bonnet with side flaps that covers the ears is now known as a Phrygian bonnet, a fame that turned to notoriety when that headwear, decorated with a rosette in the French colours, became a trademark of the French revolutionaries. Supporters of the Jacobin cause (such as William Blake) took to wearing the Phrygian bonnet as a sign of solidarity with the revolutionaries. In the present elegy, G. sticks closely to the Ovidian source and offers no hint that he may have the bonnet of the French Revolution (of which he disapproved) in mind at all.

One of Midas' servants, whilst cutting the king's hair, noticed the asses' ears. He did not dare reveal what he had seen, but driven to speak the secret somehow, he dug a shallow hole, spoke the secret into it and then covered up the hole with soil. A bed of reeds grew on the spot and a year later, waved by a gently south wind, the reeds whispered out loud the secret he had confided to the earth.

der nächste Diener: The servant was close to him, a trusted man, since he was cutting Midas' hair 'with steel'.

Schwerer wird es nun mir: 'it will be even more difficult for me' to stay silent, alluding to the pressure the servant felt to tell his secret: um sich zu erleichtern, 'in order to relieve himself' of the burden. The American songwriter Paul Francis Webster, clearly a classical scholar and a close reader of the Römische Elegien, developed the theme in his song Secret Love, which was performed most memorably by that goddess Doris Day in the film Calamity Jane (1953).

dem Hain, den schallenden Felsen: G. seems to be alluding to a Propertian elegy, 1.18:

This is certainly an empty spot, a hidden place suitable for a complainer, and only the breath of the west wind fills the solitary grove. Here one can release hidden grief freely, if only the solitary rocks stay faithful.

[…]

But whatever kind you are, let the woods echo the name 'Cynthia' / and the deserted rocks shall hear your name. [31-32]

Haec certe deserta loca et taciturna querenti, / et vacuum Zephyri possidet aura nemus. / hic licet occultos proferre impune dolores, / si modo sola queant saxa tenere fidem. [1-4]

…

sed qualiscumque's, resonent mihi 'Cynthia' silvae, / nec deserta tuo nomine saxa vacent.

Alinde

der Nachbar: Presumably G.'s nosy neighbour(s) in Rome, the one with the dog in Elegy XX.

den Quiriten: The citizens of Rome.

Commentary

It could be argued that this elegy is as much about Weimar and Goethe's liason with Christiane Vulpius as it is about his Roman affair. But in the gossip mill of the Weimar court, all discretion about Christiane would have been wasted.

His situation in Rome was very different: largely insulated by his incognito but still under threat from any gossip which spies and narks could utilise, discretion was desperately important, though not terribly difficult to achieve. In Weimar, discretion was hardly possible. We should probably take this elegy at its face value, as a contribution to that eternal theme, the heart, overflowing with passion, that dare confide in no one.

This elegy is a pendant to its immediate predecessor, Elegy XXII, which described the dangers of gossip and the immense power of Cupid – a.k.a sexual attraction – to make fools of the greatest hero and bring down the greatest reputations. In the present elegy, we learn that if Cupid has pierced you with one of his shafts, and you are following the advice of earlier elegies to act promptly to obtain your desire, the best thing to do is keep your mouth shut about the whole thing.

Goethe serves his erotic soup with moral dumplings, since a core function of mythology is to represent the ways of god to man. Each elegy may in various degrees be erotic, but it also in a sense a homily; the present one is no exception.

XXIV Epilog [n4]

Hinten im Winkel des Gartens, da stand ich, der letzte der Götter,

1Rohgebildet, und schlimm hatte die Zeit mich verletzt.

Kürbisranken schmiegten sich auf am veralteten Stamme,

3Und schon krachte das Glied unter den Lasten der Frucht.

Dürres Gereisig neben mir an, dem Winter gewidmet,

5Den ich hasse, denn er schickt mir die Raben aufs Haupt,

Schändlich mich zu besudeln; der Sommer sendet die Knechte,

7Die, sich entladende, frech zeigen das rohe Gesäß.

Unflat oben und unten! ich mußte fürchten ein Unflat

9Selber zu werden, ein Schwamm, faules verlorenes Holz.

Nun, durch deine Bemühung, o! redlicher Künstler, gewinn ich

11Unter Göttern den Platz, der mir und andern gebührt.

Wer hat Jupiters Thron, den schlechterworbnen, befestigt?

13Farb und Elfenbein, Marmor und Erz und Gedicht.

Gern erblicken mich nun verständige Männer, und denken

15Mag sich jeder so gern, wie es der Künstler gedacht.

Nicht das Mädchen entsetzt sich vor mir, und nicht die Matrone,

17Häßlich bin ich nicht mehr, bin ungeheuer nur stark.

Dafür soll dir denn auch halbfußlang die prächtige Rute

19Strotzen vom Mittel herauf, wenn es die Liebste gebeut,

Soll das Glied nicht ermüden, als bis ihr die Dutzend Figuren

21Durchgenossen, wie sie künstlich Philänis erfand.

In a corner at the back of the garden, there I stood, the last of the gods, misshapen, injured by the passage of time.

Pumpkin tendrils wrapped around the aged trunk and the member broke under the weight of the fruit.

Scrawny branches next to me, ready for winter, the season I hate, because it sends the raven onto my head,

To soil me shamefully; the summer sends the lad, who, emptying his bowels, insolently shows me his bare behind.

Crap, above and below! I was in fear of becoming crap myself, a sponge, rotting ruined wood.

Now, thanks to your efforts, O! honest artist, I gain the place amongst the gods that is worthy of me and of others.

Who secured Jupiter's throne, so dubiously acquired? Paint and ivory, marble and bronze and poetry.

Now intelligent men look at me happily and everyone likes to think the way the artist did.

No girl is shocked by me, and no matron either, I am no longer ugly, but monstrously strong.

Because of that your impressive rod should stick out half-a-foot long from the middle upwards when the loved one commands it

and the member shall not tire until it has enjoyed the dozen positions which Philänis inventively devised.

Notes

im Winkel des Gartens: The allegorical poetic garden introduced in the Prolog, watched over by the statue of Priapus.

Priapus is the farmer's god described by Tibullus in one of his his rustic moments:

Ceres of the golden hair, from my farm comes a wreath of corn-ears to hang on the outside of your temple doors. The fruit-laden gardens are consigned to the protection of the red-painted Priapus, to scare the birds with his cruel sickle.

Flava Ceres, tibi sit nostro de rure corona / Spicea, quae templi pendeat ante fores, / Pomosisque ruber custos ponatur in hortis, / Terreat ut saeva falce Priapus aves. / Vos quoque, felicis quondam, nunc pauperis agri / Custodes, fertis munera vestra, Lares.

Tibullus 1.1:15-20.

der letzte der Götter: Priapus is the 'last of the gods'. G. is writing erotic elegies, not epic poetry, so we should not be surprised to find that there is no systematic or coherent cosmogeny or history presented explicitly in the Römische Elegien. Priapus' lowly status is explicitly mentioned in poem 63 of the Carmina Priapae: interque cunctos ultimum deos numen, [I am] 'amongst all the gods the lowest'.

Nevertheless, the various ancient understandings of the great historical ages of the world – gold, silver, bronze, iron, clay – is implicit, with its view of the corruption of the modern. We experience them in the form of various grumbling asides: a hint of the Vorzeit, the 'ancient times' (Lebe glücklich, und so lebe die Vorzeit in dir!); the ruins of Jupiter's temple (Fielen des Vaters Tempel zu Grund); the modern Romans too lazy to make Ceres' garland themselves (Der für Ceres den Kranz selber zu flechten verschmäht). The tone is not completely despairing: the gods may have left, but Rome itself has been at least physically reborn from the ashes of the Dark Ages (Aus den Trümmern aufs neu fast eine größere Welt!).

Many gods play sometimes substantial parts in the Römische Elegien: Jupiter, Juno, Venus, Bacchus, Ceres, Mercury and, of course, Cupid. But Priapus is the most dominant. He is the principal and only character in the Prolog and the Epilog, which bookend the collection. If Cupid, mischievous and dangerous, as Elegy XXII tells us, is the most visible figure in the poems between those bookends, then Priapus is omnipresent, though usually invisible in the background, paring his… – oh, never mind. G.'s 'pantheon elegy', XIII, tells us as much: – Sollte der herrliche Sohn uns an der Seite nicht stehn?, 'Should the impressive son not be standing at our side?'

On a much more prosaic level, G.'s idea for Priapus as being the 'last of the gods' seems to be an allusion to poem 88 in the Carmina Priapea, attributed to Catullus or Vergil. The poem takes the form of a speech by Priapus. He is indeed one of the lesser gods, meaning that he does not reside on Olympus (hence his association with gardens and earthly locations) nor can he accept blood sacrifices, since these are reserved exclusively for the pantheon of the great gods. His 'lastness' is reinforced by his primitive construction and the conditions he must endure.

In this context, some sections of Poem 88 are worth quoting at length, whilst we ponder the principal gods on Olympus, eating ambrosia, drinking nectar, with nice hairdos and beach-bodies and compare their godlike existence with the crudely formed Priapus exposed to the elements all year round:

This place, youths, and this country cottage thatched with rushes, osier-twigs and bundles of sedge, I, carved from a dry oak by a rustic axe, now watch over, so that they thrive more every year. For its owners, the father of the poor hut and his son – both peasants – revere me and look to me as a god; the one labouring with assiduous diligence to keep the thick weeds and bushes away from my sanctuary, the other often bringing me humble offerings with open hand. On me are placed a colourful wreath of the first spring flowers and the green blade and ear of the soft corn; saffron-yellow violets, the milky poppy, pale gourds, sweet-smelling apples, and the red grapes grown in the shade of the vine. Sometimes, (but keep this to yourselves) [because the great gods will be angry at an underling such as Priapus receiving a blood sacrifice] even the blood of the bearded kid or the horn-hoofed she-goat sprinkles onto my altar: for such honours Priapus is duty bound to guard carefully the garden and the vineyard of his master.

Hunc ego, o iuvenes, locum villulamque palustrem / tectam vimine iunceo caricisque maniplis, / quercus arida rustica fomitata securi / nutrior: magis et magis fit beata quotannis. // huius nam domini colunt me, deumque salutant / pauperis tuguri pater filiusque adulescens, / alter assidua cavens diligentia, ut herbae, / aspera ut rubus a meo sit remota sacello, / alter parva manu ferens semper munera larga. // florido mihi ponitur picta vere corolla, / primitus tenera virens spica mollis arista, / luteae violae mihi lacteumque papaver / pallentesque cucurbitae et suave olentia mala, / uva pampinea rubens educata sub umbra; // sanguine haec etiam mihi (sed tacebitis) arma / barbatus linit hirculus cornipesque capella. / pro quis omnia honoribus nunc necesse Priapo est / praestare, et domini hortulum vineamque tueri. …

Priapea latina, Appendix Vergiliana (Priap. III), Poem 88.

Tibullus, the Roman elegist of the rural life, was unsurprisingly a fan of Priapus and mentions him frequently, for example:

‘O Priapus, that shade be yours and that sun and snow may never harm your head, what is your trick for captivating beautiful boys? After all, your beard's not oiled, your hair is uncombed, naked you endure the extended frost of winter and naked, the dry season of the summer dog-star.'

'Sic umbrosa tibi contingant tecta, Priape, / Ne capiti soles, ne noceantque nives: / Quae tua formosos cepit sollertia? certe / Non tibi barba nitet, non tibi culta coma est, / Nudus et hibernae producis frigora brumae, / Nudus et aestivi tempora sicca Canis.'

Tibullus 1.4:1-6.

Compare the kind and respectful treatment given to Priapus by the humble rustics with the neglect and contempt that he has experienced until rescued and restored to his rightful importance by G.'s verses.

Rohgebildet: Ill-shaped, misformed. The tradition was that the statues of Priapus in general use in gardens and on farms were not made by skilled artists in stone or marble, but simply hacked out of wood by the peasants. Again and again in the Carmina Priapea we are told that these figures were made of wood – seemingly whatever wood was lying around – and crudely formed with axes or carved and whittled with knives. In poem 63, for example, we read that manus sine arte rusticae dolaverunt, 'the hands of a rustic have chopped me'.

Not much effort was expended on subtleties such a facial expressions, the main thing was that the identifying characteristic of Priapus was immediately obvious; a dab or twelve of red paint on it would not come amiss either. The great gods, who represented the higher human traits, liked to keep up appearances. Unlike them, only one thing was on the mind of Priapus and that was certainly not his hairdo or a six-pack.

Did the Romans really think that this vulgar statue would protect their garden? Well, the popularity of such statues certainly suggests that. We must not forget that the Romans were madly superstitious and this superstition worked both ways, for both the gardener and the thief. In the mind of a thief, a well-kept statue might well have a deterrent effect; a neglected and decrepit one less so.

schlimm hatte die Zeit mich verletzt: In this and the passage it introduces, G. seems to be describing the desuetude of the veneration of Priapus, including, we assume, the various fertility cults around Bacchus and Ceres. Priapus had been the most popular god and the most widespread cult figure in the warm, superstitious and polytheistic Roman Empire. The barbarian hordes, the chilly Dark Ages and the rise of Christianity, a religion with one jealous, monomaniacal and sexually uptight god put an end to that nonsense. In the course of the centuries, the western world turned to idolising a virgin and putting her statues everywhere. This time did indeed damage Priapus badly.

In the Carmina Priapea there are numerous instances of Priapus' suffering for his outdoor life. Goethe could have taken inspiration from any of them, but a possible candidate for his source is poem 63:

Isn't it enough, friends, that I have found my abode here, where the earth cracks open in the heat of the dog days, and that I daily endure the drought of summer; Isn't it enough that the rains run down my breast, that hail-storms beat down on my bare head, and that my beard is frozen stiff with ice?…

Parum est mihi, quod hic fixi sedem / agente terra per caniculam rimas / siticulosam sustinemus aestatem? / parum, quod hiemis perfluunt sinus imbres / et in capillos grandines cadunt nostros / rigetque dura barba vincta crystallo?

Kürbisranken…veralteten Stamme: Stamm could refer to the column on which the torso of Priapus stood or, more probably in the context of his broken member, his member itself.

Gardeners will have already noted with interest that Priapus has been consiged to the corner at the back of the garden. That he is now overwhelmed by pumpkins (or gourds) tells them that he is in or next to the compost heap, the place where traditionally pumpkins are grown. Poem 63 of Carmina Priapea appears to have been G.'s inspiration: interque cunctos ultimum deos numen / cucurbitarum ligneus vocor custos, [I am] 'amongst all the gods the lowest, called the custodian of the gourds'.

die Raben: Readers might like to see the black ravens as symbols of Christian clerics, in their dark overcoats or black cassocks (im dunklen Surtout). The ravens evacuate their bowels on poor old Priapus, which is a reasonable metaphor for nearly two millennia of history.

But G.'s immediate inspiration for the incontinent ravens may have come from the poem Quid hoc novi est? in the Vergilian Appendix of the Carmina Priapea, where we read of the 'ancient raven or the busy jackdaw pecking your head with its horny beak' (senexve corvus impigerve graculus / sacrum feriret ore corneo caput.)

Unflat oben und unten: 'crap', 'filth' or 'manure' above and below. Once again our gardening readers have the advantage of easily visualising poor old Priapus in his compost heap, manure at his feet and bird droppings on his head. G., always the master of scene setting.

ich mußte fürchten ein Unflat…faules verlorenes Holz: It seems reasonable also to apply this statement to Goethe's metaphorical situation in Weimar before he decided to break free and flee to Italy – that moment of 'midlife crisis' filled with despairing self-analysis.

durch deine Bemühung…der mir und andern gebührt: Our perception that Priapus is really the god behind the Römische Elegien is reinforced here, where he thanks G. for recovering him from neglect and insults and restoring him to his proper place among the gods. We must inevitably return to the 'pantheon elegy', XIII, to find Priapus' fitting place among the gods on Olympus: Sollte der herrliche Sohn uns an der Seite nicht stehn?

The Renaissance and the Enlightenment together rediscovered the world that disappeared when the classical world was swept away by the Dark Ages in western Europe. G. asserts that the Römische Elegien are a contribution to the great European Zeitgeist of the times. As we find so often to be the case with G., he is thinking in great analytical sweeps. Leaving aside the question of whether these analytical sweeps are right or wrong, we have to wait for the ascent of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche before we find the same courage to think radically outside the Christian tradition.

Wer hat Jupiters Thron, den schlechterworbnen, befestigt?: Jupiter acquired his throne as the 'father of the gods' by means of the overthrow of the Titan Cronus, who in turn had gained it by the assassination of Uranus. Following this, it was the sexual passion of Jupiter and Juno who created what came to be the pantheon of gods on Olympus. Hence we might at first think that it was Priapus, the god of lust and desire, who ultimately befestigt, 'secured' Jupiter's position.

Farb und Elfenbein, Marmor und Erz und Gedicht.: This line directly answers Priapus' question about the responsibility for securing Jupiter's position. This line takes us a step beyond Priapus' lustfulness as a factor in the existence of the classical pantheon. The factors are 'paint and ivory, marble and bronze and poetry'. In other words, the gods live and live on as a result of the representations of them in art and culture, ultimately as a result of the efforts of artists down the ages: the painters, carvers, sculptors and poets.

This concept returns us to Elegy II, the first lines of the first elegy after the Priapic prolog: es ist alles beseelt in deinen heiligen Mauern. We now understand, if we did not before, that these pantheistic souls of artistic creations and the genius loci of Rome 'secure' the classical heritage and its pantheon.

The task of securing that information falls to the artist, as W. B. Yeats pointed out in his great epitaph poem Under Ben Bulben:

Poet and sculptor, do the work,

Nor let the modish painter shirk

What his great forefathers did,

Bring the soul of man to God,

Make him fill the cradles right.

W. B. Yeats, 'Under Ben Bulben', stanza IV, in Collected Poems, Macmillan, London, 1965, p. 399.

verständige Männer: 'men of understanding'. With this phrase in our minds, possibly in the form of 'those in the know', we might think of the enlightened ones of the Eleusinian Mysteries: die Eingeweihten; we might even transfer the circle of admirers from Priapus to his poet G., recalling those who received the Römische Elegien with goodwill and understanding; we might even think of Carl August, G.'s 'understanding' duke.

künstlich Philänis erfand: Philaenis of Samos was supposed to be the author of an ancient sex manual. No one knows who she was or whether she was a real person. Her sex manual no longer exists – and may not even have existed in such a form – but was mentioned in several other authors. A specific source of G.'s 'dozen positions' is unknown to your author. Catullus, that wuzz, appears to be familiar with only nine positions, but several other authors settle for the dozen.

Philaenis is mentioned in passing in the Carmina Priapea, speaking of a girl who, unless she is serviced in every position described by Philaenis, storms off still raging with lust (quae tot figuras, quas Philaenis enarrat, / non inventis pruriosa discedit).

Commentary

Most of the comments on Elegy I, the Prolog and the first 'bookend' of the collection also apply to the present elegy, the second 'bookend'.

The present elegy is more than twice as long as Elegy I and ties up some of the themes from the collection – which is what we might expect from something titled Epilog.

What we don't expect, however, is the immense sweep of this elegy's allegorical presentation of the cultural decline and fall since the days of the ancient classical gods, whether those of Greece or Rome.

Priapus' journey down the ages has taken him from a general popularity among the common people, through desuetude during the one and a half millennia of the repressed sexuality of the Christian world. He has now, thanks to the efforts of the 'honest artist' Goethe, come back into his own in the poems of the Römische Elegien.

It's a wild claim – the modern pornographers, now in every corner of modern culture thanks to the internet, all burst out laughing; but we have to consider Goethe's cultural environment then, not ours now. Both the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation spread sexual repression throughout European culture.

The generation of writers in German before Goethe and those of his generation, making the best of a bad job, had tried to spread sublimity and delicacy and suppress all the 'baser' passions – those ones that support the essential function of producing babies, for example. Condensing a fifty page thesis into one sentence: the writers before, during and for a long time after Goethe's time poured their efforts into avoiding writing about sex. They could write about bible stories, classical gods, seasons, birds and flowers; the doings of rustics were of endless interest to them – but just not their procreative doings.

The tradition of nudity in the visual arts was still applicable to classical or religious subjects, but whereas the classical artists had no inhibitions when it came to the organs of generation (particularly Priapus' fine specimen), the artists of Goethe's Europe would go to extraordinary lengths to hide these. In Britain, Flaxman (1755-1826) and Blake (1757-1827) – along with everyone else – emasculated mythological figures completely, thus removing the generative principle entirely. Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825) did this too in his 'official art', keeping his priapic works for sale under the counter.

Even the engravings in the published works about the treasures of the ancient world were ruthlessly bowdlerised. Priapus is the litmus test: he was scarcely mentioned and rarely illustrated, because that would require talking about and illustrating his main feature. All these artefacts are evidence for a society in a declined state.

Your author digs out from the dusty hole in which it has passed the last fifty years the Smaller Classical Mythology by William Smith LL.D., published by John Murray in 1867, intended 'for the Use of Schools and Young Persons'. The Preface tells us that:

The following Work has been prepared by a lady, for the use of schools and young persons of both sexes. In common with many other teachers, she has long felt the want of a consecutive account of the Heathen Deities, which might be safely placed in the hands of the young, and yet contain all that is generally necessary to enable them to understand the classical allusions they may meet with in prose or poetry, and to appreciate the meaning of works of art, — for Mythology is not to be regarded merely as a branch of classical study.

There is an entry for Priapus, but a remarkably unpriapic one. If you cannot bring yourself to inform the child about Priapus' chief characteristic, you may as well fill up the space with dissembling and unimportant details:

Priapus, another son of Dionysus and Aphrodite, was a god of fertility and agriculture; he was born at Lampsacus, on the Hellespont, shortly after the return of Dionysus from India. As Aphrodite had displeased Hera by her conduct, the latter ordained that this child of the offending goddess should be extremely ugly. Priapus was worshipped at Lampsacus, whence he is sometimes called Hellespontiacus; and in Italy, where he was represented by Hermæ, usually painted, like those of other rustic gods, red, — whence he is also called ruber, or rubicundus. His images represent him carrying fruit in his garments, and a sickle or cornucopia in his hand. His offerings consisted of the first-fruits of gardens, vineyards, and fields, and of milk, honey, cakes, rams, asses, and even of fishes.

In 1867, should a suitable covering – a bunch of fruit, a wisp of cloak – not be to hand, the scalpel always was:

It is in this context that we have to view the indisputable fact that Goethe placed Priapus at the beginning and end of his Römische Elegien, or Erotica Romana, as he once titled them. Priapus was the god who should have been standing at the side of Bacchus and Venus in the pantheon of the gods in Elegy XIII.

The next most important god in the Römische Elegien is Cupid, the mischievous, anarchic, irresistible god who likes nothing better than to make fools of pompous heroes (Elegy XXII). Both he and Priapus are forces of Nature, as it were, destructive of order, of pomposity and hypocrisy. Priapus was 'disappeared' from the general culture of Europe and Cupid, the beautiful boy, became a harmless, chubby little putto.

Irony is never far away: the Prolog and Epilog, the Priapic bookends for the collection, went unpublished for well over a century, emasculating the Römische Elegien as surely as any papal castrato – the collection has sung in a false register ever since. Even today, it is rare to find the Römische Elegien published intact. The reader strolling round Goethe's erotic garden has to take the machete and hack back the overgrown hedge to reveal the god who, more than any other figure, stands behind these poems, flaunting his member.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!