Quote and image of the month 11.2020

Posted on UTC 2020-11-01 05:02

Giovanni Giacometti, Nebbia (Maloja), 1910

Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933), Nebbia (Maloja), 'Fog (Maloja)', 1910. Image: Kunsthaus Zürich, Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde, 1962. [Click to view a larger version in a new browser tab.]

This painting is by the Swiss artist Giovanni Giacometti (1868-1933) – no not THAT Giacometti (the 'spindly people' Giacometti), THAT Giacometti was Alberto (1901-1966), Giovanni's son.

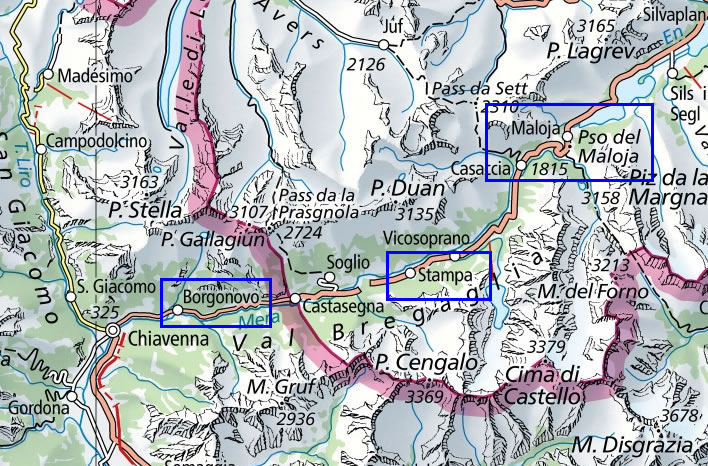

Giovanni spent most of his life in the Maloja region of Graubünden in Switzerland. Alberto and his three siblings were born in the village of Borgonova, on the route between Chiavenna in the north of Italy and Silvaplana in the Engadin valley in Switzerland.

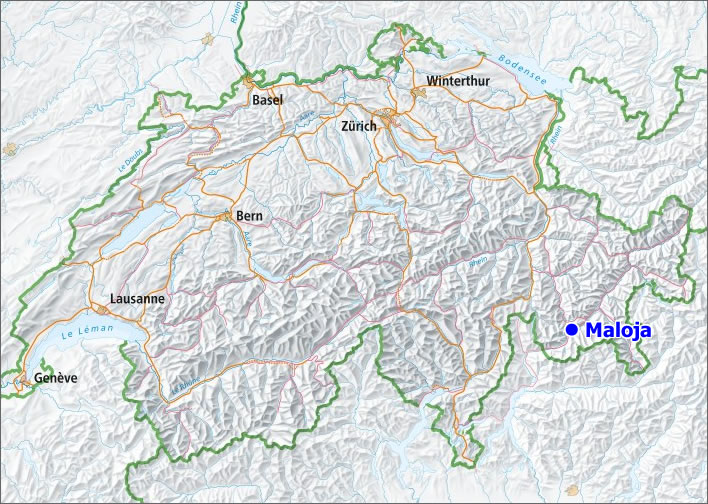

A map of Switzerland showing the location of Maloja [pron. Maloya] village and the nearby Maloja Pass. To be boringly precise, the village is located in the community of Bregaglia and gives its name to the region of Maloja, part of the Oberengadin (Upper Engadin) in the canton of Graubünden. Base image: ©Bundesamt für Landestopografie swisstopo.

The title of the painting refers (probably) to the village of Maloja (1809 m), about 15 km further along the route from Borgonova, over the spectacularly twisty Maloja Pass. In 1904 the Giacomettis moved from Borgonova to Stampa, 2 km along the pass route.

The pass route between Chiavenna and the Silvaplanasee in the Oberengadin showing the villages of Borgonova, Stampa, the Maloja Pass and the village of Maloja. Base image: ©Bundesamt für Landestopografie swisstopo.

The reader should recall that we are considering a time before Switzerland fell in love with tarmacadam and concrete, before the Maloja Pass route became merely a looped and twisted cord of headlights and tailights in the alpine night.

Winter sun and fog at 1,400 m (not Maloja). Image: ©FoS [reuse only with link to this page].

Hermann Hesse, Im Nebel, November 1905.

|

Im Nebel

Seltsam, im Nebel zu wandern! Einsam ist jeder Busch und Stein, kein Baum sieht den andern, jeder ist allein. |

In Fog

How strange it is to walk in fog! Every bush and stone is alone, no tree can see the other, each is alone. |

| Voll von Freunden war mir die Welt, als noch mein Leben licht war; nun, da der Nebel fällt, ist keiner mehr sichtbar. |

My world was full of pleasures when my life was light; now, since the fog fell, no one can be seen. |

| Wahrlich, keiner ist weise, der nicht das Dunkel kennt, das unentrinnbar und leise von allen ihn trennt. |

Truly, no one is wise who does not know the darkness which inescapably and quietly separates him from everything. |

| Seltsam, im Nebel zu wandern! Leben ist Einsamsein. Kein Mensch kennt den andern, jeder ist allein. |

How strange it is to walk in fog! Life is being alone. No person knows the other, each is alone. |

Hermann Hesse (1877-1962), Im Nebel, 'In Fog'. This text is taken from Hermann Hesse, Die Gedichte, Berlin 1947. Translation ©Figures of Speech 2020, reuse in whole or part only with link to this page.

Hermann Hesse reading Im Nebel, date unknown. More proof, if any were needed, that poets are usually the last people who should read their own work.

Despite heroic efforts over the years, your author really cannot warm to Hermann Hesse's prose or poetry. He cheerfully admits that this is more a deficiency in him than in Hesse, who has a considerable fan base in the German-speaking world.

In that German speaking world Im Nebel is a well known poem. Many innocent schoolchildren are required at some point in their school career to write an 'interpretation' of it – which seems to your author to be a cruel and unusual punishment to inflict on the young. Every idea in the poem lies on its surface, so requiring children in pursuit of good marks to hunt for depths where none exist strikes him as a little sadistic. Any independent-thinking, perceptive child who took the poem apart in such an 'interpretation' might end up in hot water.

Hesse went through periods of depression; we imagine that this poem arose out of one of those.

The first stanza starts to walk us through the fog, then marches straight into the pathetic fallacy that because of the fog, bushes, stones and trees can no longer 'see' each other and are therefore einsam, 'alone'. The poem was written in 1906, when there was still a lot of pathetic fallacy around in poetry, but anyone who cares for language should not wander into this swamp.

In an attempt to spare the poem from self-destruction in its second line, your author chose not to translate einsam as the more obvious word 'lonely', in order to save Hesse from the same sort of hilarity that greets the Wordsworthian wanderer's 'lonely' cloud above the 'host' of 'dancing' daffodils. The last line gives us allein, an exact a synonym of einsam, and then generalises the isolation/loneliness with the wishy-washy jeder, 'each/every' bush|stone|tree – an ambiguity that will be picked up in the final line of the poem.

The second stanza requires little explanation. The use of the word licht, 'light' (adjective) is quite clever, but cannot save the stanza from the crass ineptitude of the last line: ist keiner mehr sichtbar belongs in a police incident report or a washing machine service handbook.

The third stanza is also a straightforward representation of the depressed mind, but also comes a cropper on poetic ineptitude: wahrlich, 'truly', is not a word that belongs in any poem, let alone as the first word of a stanza; der Nebel ,'fog', has become, for the exigencies of this stanza alone, das Dunkel, the 'darkness', which, however, is never used again.

The final stanza begins and ends with the same lines as the first stanza, resolving the ambiguity of jeder into 'each person'. Unfortunately, the two lines in the middle are a cheap rhetorical trick: so far we have heard about the experience of depression for the individual sufferer through the metaphor of fog or darkness descending; now, apparently, Leben ist Einsamsein, that is, 'life [itself] is being alone/lonely' – the individual's depression has become the condition of humanity as a whole.

Similarly, Kein Mensch kennt den andern, 'No person knows the other', is characteristic Hesse hyperbole, since he has forgotten in his current darkness that his own life was once licht and full of friends. In order to make sense of these two lines we would have to read Leben [im Nebel] ist Einsamsein. / [In diesem Nebel] kennt kein Mensch den andern, 'Life in this fog is being alone. / In this fog no person knows the other'.

German speakers grow up with doggerel such as this and think it somehow deep and worthy of being taken seriously. English speakers grow up with doggerel from Wordsworth or Maya Angelou (and many in between), ditto ditto. Will this fog ever lift?

Hermann Hesse, 1926? Image: unknown source.

A chapter of fogs

Fog in the alps is not the same dark grey substance that blights the lives of the inhabitants of lowland areas; seen from the mountains, lowland fog pools in the valleys and creates lakes of white that settle darkly on the people below – people such as Hermann Hesse.

Images: ©FoS [reuse only with link to this page].

Alpine fogs are quite different from lowland fogs, being usually lucent things, which cling to forests and crags, or form the ghostly shadows of baubuzi (Romontsch), babau (Italian), 'hobgoblins' – spectres with which to frighten children. This spectral play of light on the imagination is the kind of fog that Giovanni Giacometti and his family would have known, a gauziness that may be a function of altitude and also perhaps result from the lack of suspended particulates and aerosols in the much purer air.

In addition, clouds of water droplets are an optically active medium that can refract and scatter light from low sun angles in many remarkable ways. Giacometti's seemingly adventurous choice of colour in Nebbia acknowledges as much.

And finally, being in a cloud – whether a lonely or gregarious one – sounds much sublimer than being in a fog.

Images: ©FoS [reuse only with link to this page].

Alpine fogs rise up around you or sweep in on you laterally. They do not sink down on top of you.

Image: ©FoS [reuse only with link to this page].

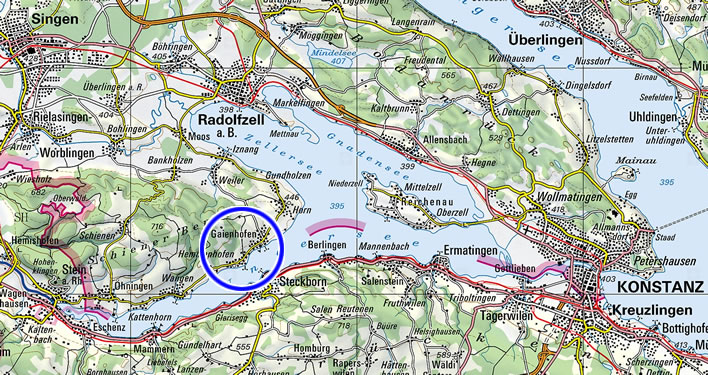

At the time of the writing of Im Nebel Hermann Hesse was living in Gaienhofen (1904-1912), a village on the shore of the Untersee, at the northwestern end of the Bodensee, the Lake of Constance.

The village of Gaienhofen, in Baden-Württemberg in Germany, on the shore of the Untersee. Base image: ©Bundesamt für Landestopografie swisstopo.

A great lowland basin known as the Swiss Plateau extends from the hills of the Black Forest and Swabia in the north down to the foothils of the Swiss Alps in the south; it encompasses the Lake of Constance and the Lake of Zurich and is a notorious collector of fog and low cloud, particularly in the autumn and winter.

A view from the Jungfraujoch north-eastwards across the fog-filled Swiss Plateau. Image: Photo ©Ruedi Wyss, in Scherrer and Appenzeller, 'Fog and low stratus over the Swiss Plateau − a climatological study' in International Journal Of Climatology, Volume 34, Issue 3, 15 March 2014, Pages 678-686.

The residents of Gaienhofen are well placed to suffer the disipiriting effects of that dank blanket of chilly greyness that can rest over them for weeks on end. The fog does not always envelop them, but often hangs a little above them like a thick grey blanket (Hochnebel). Your author has no photos of this phenomenon: it is completely unphotogenic.

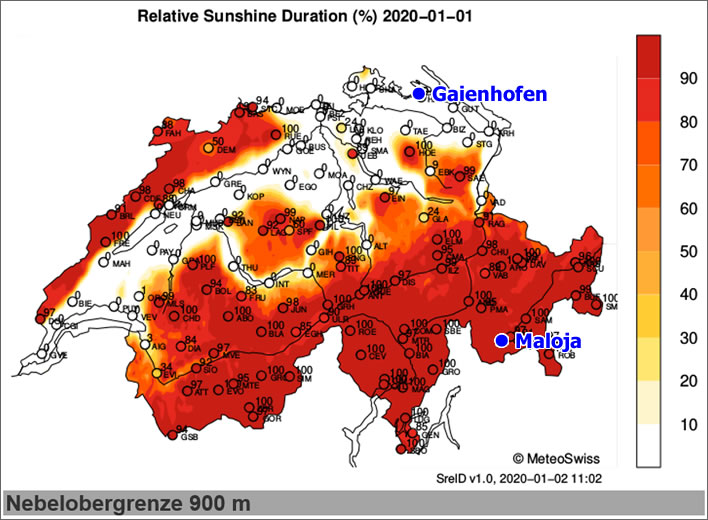

Relative sunshine duration measured on 1 January 2020 for Switzerland. On that day the Swiss Plateau (including Gaienhofen) lay under its usual blanket of cold fog resulting in no sun at all for those underneath. The inhabitants of Maloja had sun, snow and whatever other word begins with 's' for 90% of the day, meaning that they could take their New Year refreshments sitting in their shirtsleeves in their gardens, on their balconies or on the café terraces. Base image: ©MeteoSchweiz.

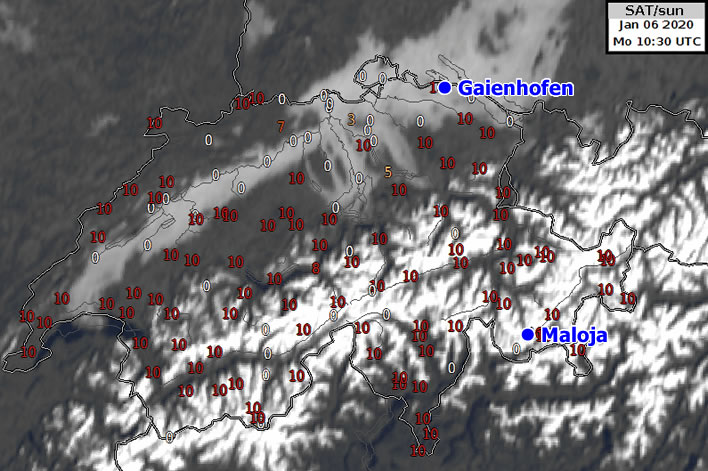

Lunchtime on 6 January 2020. The poor souls on the Swiss Plateau and particularly around the Lake of Constance are still shivering under the freezing fog, glancing upwards from time to time to see if they can catch a glimpse of the pale yellow shimmer in the sky. Typically, the fog will be there all day long. There is no doubt that after months of wandering around under this, the sensitive literary types have all sunk into a deep depression. Base image: ©MeteoSchweiz.

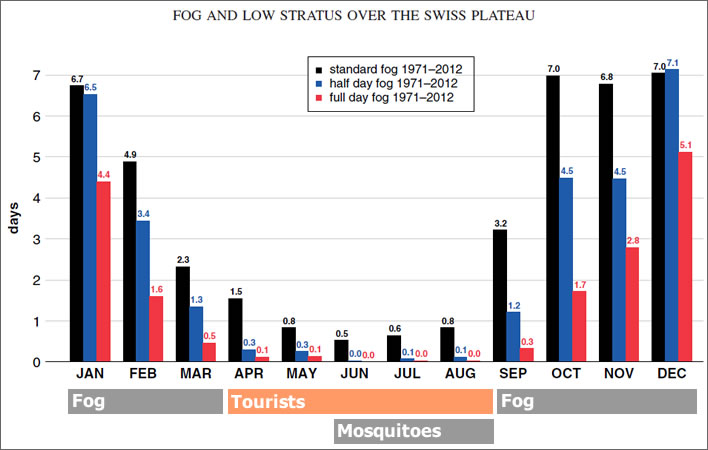

The modern inhabitants around the shore of the Lake of Constance like to make grim German jokes about their two seasons: spring/summer (tourists and mosquitoes) and autumn/winter (fog and low cloud).

The two seasons of the Swiss Plateau. Monthly fog climatologies (in days per month). Classical fog observations (black bars and numbers), at least half day FLS (FLSHD+, blue bars and numbers), and full day FLS (FLSFD, red bars line and numbers) for the period 1971–2012. Base image in Scherrer and Appenzeller, op. cit.

Once this fog has set in, the only available pleasure for the depressed sufferer is a trip to the nearest high ground to see what that pale yellow patch looks like above the fog. The moment on the climbing road when the vehicle bursts from the grey blanket into the sunshine and blue sky can only be described as epiphanic.

Who said Literary Studies wasn't a science?

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!