The chestnut tree at the gate

Richard Law, UTC 2019-08-28 09:27 Updated on UTC 2019-10-04

The horse chestnut tree before our door has had a good year. Let's have some horse chestnut photos, as our tree prepares to unburden itself on the path and in the stream:

20 April 2019 – spring advances. Image: Figures of Speech.

5 May 2019 – winter fights back. Image: Figures of Speech.

31 May 2019 – May gets nature back on track. Image: Figures of Speech.

28 June 2019 – After its success in setting seed, in the space of a few days the tree will discard those offpring which it cannot support. It seems to have its own assessment of its energy budget for the rest of the summer and the autumn. Image: Figures of Speech.

27 August 2019 – so far, so good. The bombardment will begin shortly. Image: Figures of Speech.

Whenever I pass the tree I almost always recall the chestnut tree in Hermann Hesse's (1877-1962) novel Narziss und Goldmund (1930).

Yes, yes… I know: Hesse's tree was the Edelkastanie, the edible or sweet chestnut, Castanea sativa, as opposed to the inedible, lightly-poisonous Rosskastanien, 'horse chestnut', Aesculus hippocastanum. Since I cannot recall ever seeing a sweet chestnut tree, the horse chestnut will have to do.

Yes, yes… I know: the horse chestnut is about as closely related to the sweet chestnut as I am to Mick Jagger. But one has to work with what one has, no?

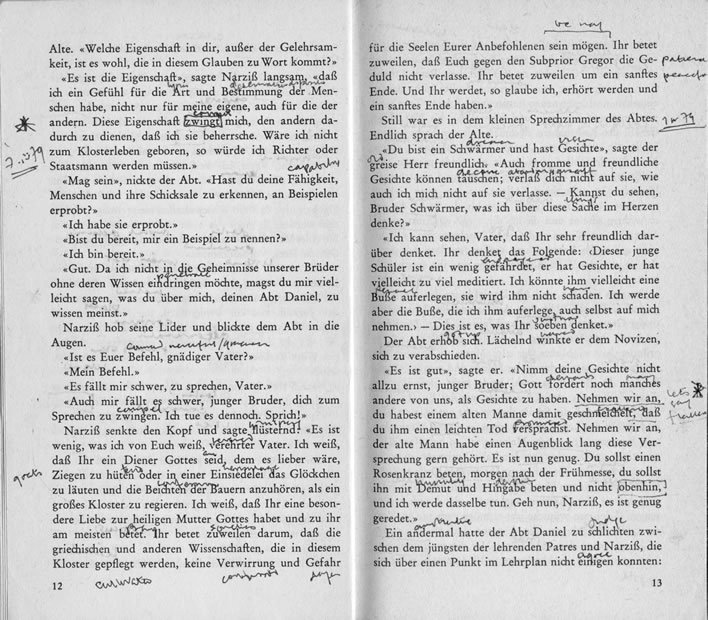

I fish out my copy of Narziss und Goldmund, intending to quote the famous opening scene which introduces the figure of the ancient sweet chestnut tree.

Yes, there it is, the old familiar Suhrkamp paperback.

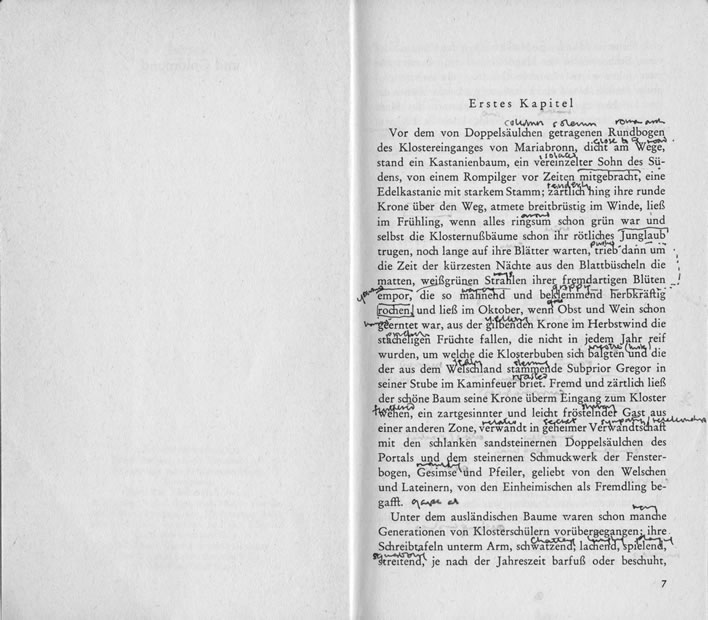

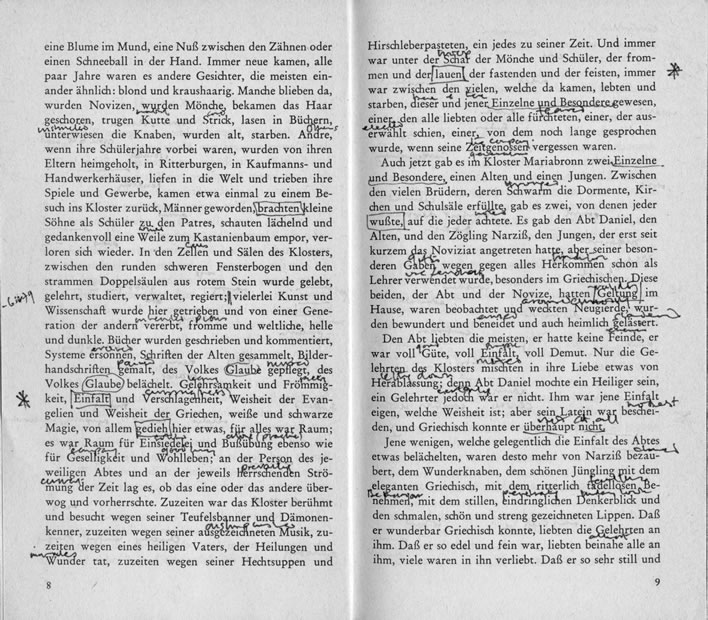

But on opening it I get a shock:

Of course. This was the very book a friend advised me to read, in order to learn some German. Dear friend!

Here it is, my studies dated, starting '6.iv.79' (the way I wrote dates before computers took over the world: no leading zeroes, Roman numerals and a two-digit year – the Y2K fright was still 20 years away).

Forty years ago. Forty years of rowing the galley to the beat of another's drum. Forty!

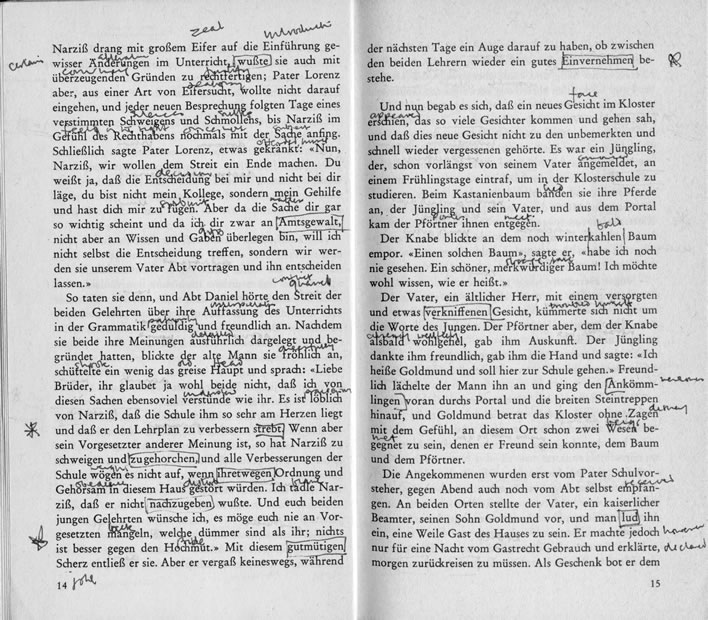

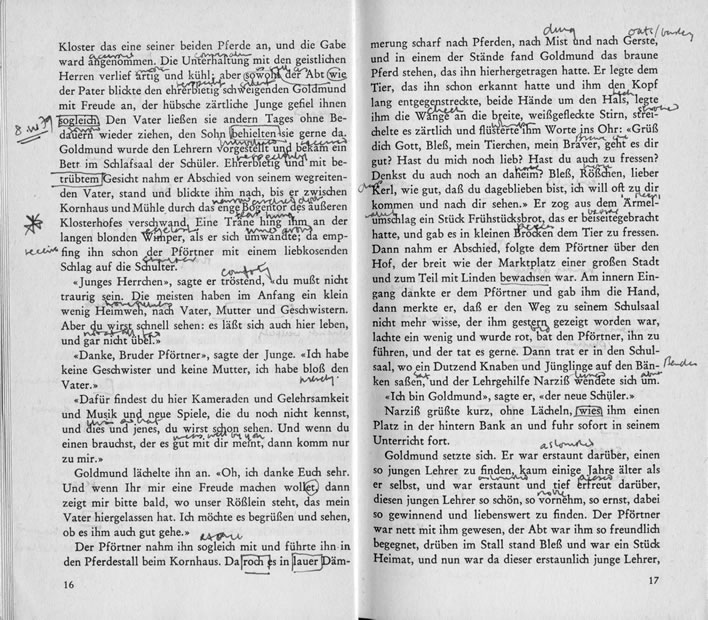

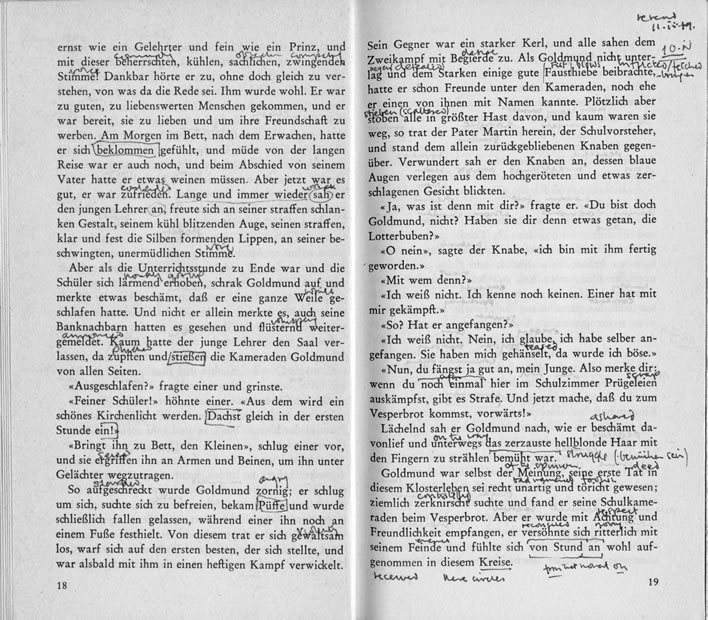

On '6.iv.79' (Friday) I completed my first page and a half of labour. The next day, '7.iv.79' (Saturday), another page and a half…

… and yet another couple of pages on that same day…

… and another page on that same day and then …

… and nearly three pages on '8.iv.79' (Palm Sunday) …

… and yet another couple of pages finished on '10.iv.79' (Tuesday), then a remark 'reread 11.iv.79' (Wednesday). Clearly, it was a dull April in 1979.

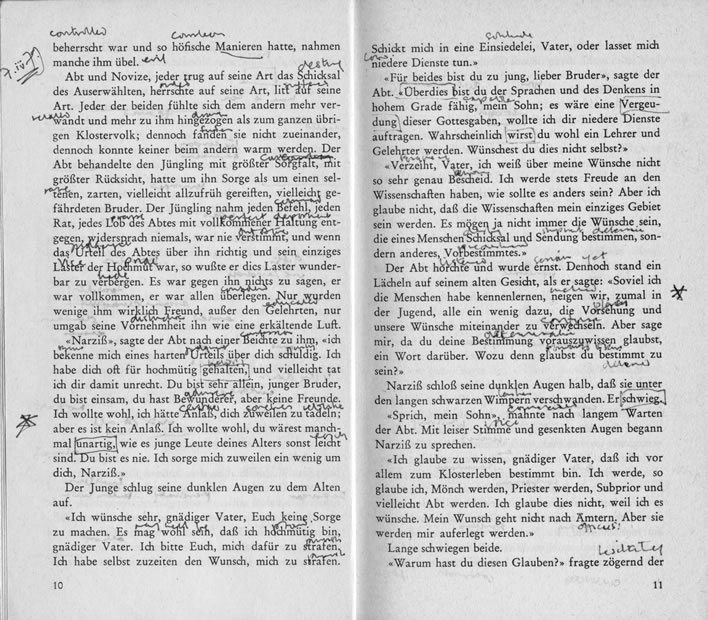

Which may be a good job, since Hermann's German had reached a crescendo of incomprehensibility:

… a page and a half brings me to '12.iv.79' (Thursday), half a page to '14.iv.79' (Saturday) …

… half a page later, '15.iv.79' (Easter Sunday) and my German education appears to be complete. This must have been the resurrection after the days of twisting on the cross of German prose. There is hardly a squiggle on any of the following pages.

My friend had clearly given me excellent advice, because it appears – the evidence is here in black and white – that by 15.iv.79 I was able to continue reading without needing to look anything more up. Job done – learning German was just a breeze. 'Dear diary. Last week I learned German. Easy peasy. Next week: Ugaritic.'

Hermann Hesse, 1926? Image: unknown source.

Returning to the book today I understood something I missed that Easter in 1979, when I was reading with the book in one hand and the dictionary in the other: the magnificent cadences of Hesse's German. You either have a soft spot for this kind of writing or you don't.

Let's look at the arching periodic cadences of a master, here in that famous first paragraph. Two hundred words in one paragraph, two sentences, almost one page. The translation is deliberately punctiliously literal; the cadences of tone and syntax are represented by the line breaks and the indented display:

Vor dem von Doppelsäulchen getragenen Rundbogen des Klostereinganges von Mariabronn,

In front of the round arch supported by double columns of the monastery entrance of Mariabronn,

dicht am Wege,

next to the path,

stand ein Kastanienbaum,

stood a chestnut tree,

ein vereinzelter Sohn des Südens,

a solitary son of the south,

von einem Rompilger vor Zeiten mitgebracht,

brought here long before by a pilgrim from Rome,

eine Edelkastanie mit starkem Stamm;

a sweet chestnut with a broad trunk;

zärtlich hing ihre runde Krone über den Weg,

its round crown hung delicately over the path,

atmete breitbrüstig im Winde,

breathed the wind in deeply,

ließ im Frühling,

let in spring,

wenn alles ringsum schon grün war

when all around was already green

und selbst die Klosternußbäume schon ihr rötliches Junglaub trugen,

and even the monastery nut trees were carrying their reddish early foliage,

noch lange auf ihre Blätter warten,

us wait a long time for its leaves,

trieb dann um die Zeit der kürzesten Nächte

pushed in the time around the shortest nights

aus den Blattbüscheln die matten, weißgrünen Strahlen ihrer fremdartigen Blüten empor,

out of the clusters of leaves the dull, white-green rays of its strange flowers upwards,

die so mahnend und beklemmend herbkräftig rochen

which smelled so admonitory and oppressive

und ließ im Oktober,

and let in October,

wenn Obst und Wein schon geerntet war,

when fruit and wine had already been harvested

aus der gilbenden Krone im Herbstwind die stacheligen Früchte fallen,

out of the yellowing crown in the autumn wind the spiny fruits fall,

die nicht in jedem Jahr reif wurden,

which were not ripe every year,

um welche die Klosterbuben sich balgten

over which the monastery children scuffled

und die

and which

der aus dem Welschland stammende Subprior Gregor

Sub-Prior Gregor, who came from Italy

in seiner Stube im Kaminfeuer briet.

roasted in the fire in his room.

Fremd und zärtlich ließ der schöne Baum seine Krone überm Eingang zum Kloster wehen,

Strangely and delicately the beautiful tree let its crown flutter over the entrance to the monastery,

ein zartgesinnter und leicht fröstelnder Gast aus einer anderen Zone,

a sensitive and lightly shivering guest from a different climate,

verwandt in geheimer Verwandtschaft mit den schlanken sandsteinernen Doppelsäulchen des Portals

related in secret relationship with the slender sandstone double columns of the portal

und dem steinernen Schmuckwerk der Fensterbogen, Gesimse und Pfeiler,

and the stone decorations of the window arches, mouldings and pillars

geliebt von den Welschen und Lateinern,

beloved of the Italians and Latinists,

von den Einheimischen als Fremdling begafft.

gawped at as aliens by the locals.

In search of Mariabronn

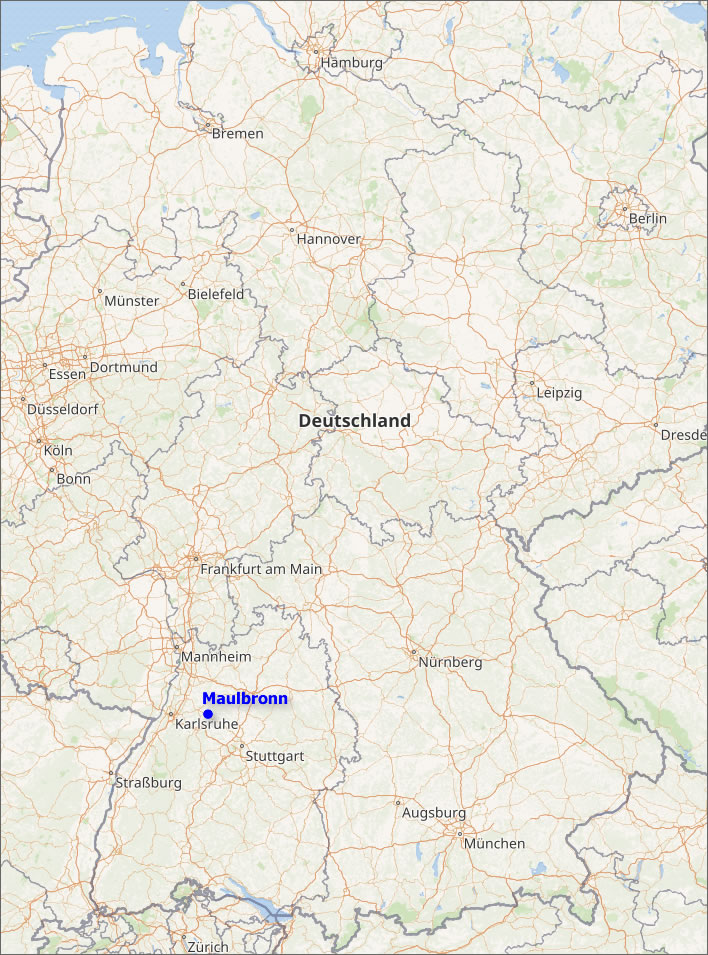

Hesse's monastery of 'Mariabronn' seems to point us to the Protestant Monastery of Maulbronn, where the fourteen year old Hesse was sent to board in 1891.

He had an unhappy time there and eventually absconded in March 1892, unable to stand the place any longer. He had one day of freedom on the run before he was caught. He attempted to shoot himself in May 1892. His next few years were restless and plagued with thoughts of suicide.

Hesse worked his experiences of those desperate years into the autobiographical novel Unterm Rad, first published in 1906. The interfaces between Dichtung, 'invention' and Wahrheit, truth' (©Goethe) are fluid for all scribblers, but it is certain that an education at the seminary in Maulbronn was not for the faint hearted.

For that other Swabian literary genius, Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843), his two years in Maulbronn (1786-1788) were just part of a series of Pietist (~Puritan) establishments, the cold physical and mental privations of which would nowadays be considered as a shockingly cruel punishment even for a serial killer, let alone a sensitive teenager. Whereas the wild and rebellious Hesse was brought to the brink of madness almost immediately, the obedient and dutiful mother's boy Hölderlin put up with it, but the Pietist curse caught up with him in his thirties and the remaining forty years of his life was spent in fragile, secluded lunacy.

Maulbronn Monastery: lime tree and entrance portal. Image: Wikimedia, H. Zell.

The remarkable portal of Mariabronn with the rounded arches which he described in Narziss und Goldmund is also a feature of the monastery of Maulbronn. A great and old tree stands before it, too, but the tree in Maulbronn is not a sweet chestnut but an ancient Linde, a lime tree. It appears to be one of the so-called Friedenslinden, 'Peace Limes' that were planted to commemorate the end of the ruinous Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Now around 350 years old, the tree is nearing the end of its days. There are plans to clone it to raise a replacement tree.

They are such liars, these scribblers! There I was feeling bad about pretending my horse chestnut was a sweet chestnut – a tree that is so rare in our chilly latitudes that I have never seen one in my life – when all along Hesse was pretending that a good, noble, German Linde was in fact an Edelkastanie. He did this, it seems, because he wanted some metaphor for the alien pilgrim from the south, now shivering here in the north. It's a good ruse, too, replacing that characteristically German tree, the Linde with that alien southerner, the Edelkastanie.

Maulbronn Monastery: the entrance portal and the tree, which is indisputably a Linde. Image: ©Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Baden-Württemberg, Günther Bayerl.

Germany, location of Maulbronn. Image: Base map: Open Street map.

Actually, I stopped in Narziss und Goldmund where I did, not because of linguistic exhaustion or having worn out my dictionary or blistering my finger or alcohol overload or even of having achieved perfection in understanding the German language. I stopped because I am simply not a fan of Hesse's way of handling of subjects and characters. His writing is really not to my taste.

If you want to learn German by 'depth-reading' a book – a technique I can only recommend – make sure it is a book you really like. That said, depth-reading fifteen pages of Narziss und Goldmund did me no appreciable harm.

Another old friend of mine, a Germanist, had an alternative suggestion: read Bild:

Siste viator

Back to where we started in this piece: our horse chestnut.

I gather its conkers up each year and scatter them along the banks of streams, increasing its chances of having progeny from 0.00 to 0.01. In another forty years one or two may have grown, may have been spared the swish of the scythe and the nibble of the deer.

I won't know anything about it, but some passer-by may pause at a fine young chestnut tree and call to mind that famous archetype that stood before the round monastery portal of Hesse's Marienbronn. Assuming of course that they, too, don't know the difference between a horse chestnut and a sweet chestnut.

Update 31.08.2019

A reader kindly sends in a photograph of a sweet chestnut that is growing in the University Botanic Garden in Leicester, displaying 'the typical corkscrew character of the trunk'. Some of the nuts can be seen on the ground. [Click to open a larger image in a new browser tab.]

Update 04.10.2019

Whilst on the subject of edible chestnuts we should take in Robert Louis Stevenson's (1850-1894) encounter with them in his travel book Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879). Stevenson was passing along the zigzag, steep-sided valley of the Tarn river in the southern part of the French Massif Central. He knew the trees as Spanish chestnuts.

A new road leads from Pont de Montvert to Florac by the valley of the Tarn; a smooth sandy ledge, it runs about half-way between the summit of the cliffs and the river in the bottom of the valley; and I went in and out, as I followed it, from bays of shadow into promontories of afternoon sun. This was a pass like that of Killiecrankie; a deep turning gully in the hills, with the Tarn making a wonderful hoarse uproar far below, and craggy summits standing in the sunshine high above. A thin fringe of ash- trees ran about the hill-tops, like ivy on a ruin; but on the lower slopes, and far up every glen, the Spanish chestnut-trees stood each four- square to heaven under its tented foliage. Some were planted, each on its own terrace no larger than a bed; some, trusting in their roots, found strength to grow and prosper and be straight and large upon the rapid slopes of the valley; others, where there was a margin to the river, stood marshalled in a line and mighty like cedars of Lebanon. Yet even where they grew most thickly they were not to be thought of as a wood, but as a herd of stalwart individuals; and the dome of each tree stood forth separate and large, and as it were a little hill, from among the domes of its companions. They gave forth a faint sweet perfume which pervaded the air of the afternoon; autumn had put tints of gold and tarnish in the green; and the sun so shone through and kindled the broad foliage, that each chestnut was relieved against another, not in shadow, but in light. A humble sketcher here laid down his pencil in despair.

I wish I could convey a notion of the growth of these noble trees; of how they strike out boughs like the oak, and trail sprays of drooping foliage like the willow; of how they stand on upright fluted columns like the pillars of a church; or like the olive, from the most shattered bole can put out smooth and youthful shoots, and begin a new life upon the ruins of the old. Thus they partake of the nature of many different trees; and even their prickly top-knots, seen near at hand against the sky, have a certain palm-like air that impresses the imagination. But their individuality, although compounded of so many elements, is but the richer and the more original. And to look down upon a level filled with these knolls of foliage, or to see a clan of old unconquerable chestnuts cluster 'like herded elephants' upon the spur of a mountain, is to rise to higher thoughts of the powers that are in Nature.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!