Gheorghe Asachi and the 'Romanian Renaissance'

Richard Law, UTC 2025-02-01 08:00

Gheorghe Asachi (1788-1869) was a Moldavian polymath and polyglot who became an outstanding figure in the cultural development of Romania. He was the intellectual driving force in the modernisation of that country. His reputation as a great Moldavian/Romanian is still intact despite all the historical mutations and ownership changes.

He was born in the town of Herța in 1788, which was then part of Moldavia. After that it became part of the Kingdom of Romania, then after that was swallowed up in 1940 by the Soviet Union. After the collapse of the USSR it became part of Ukraine. A typical change of ownership in the history of this region.

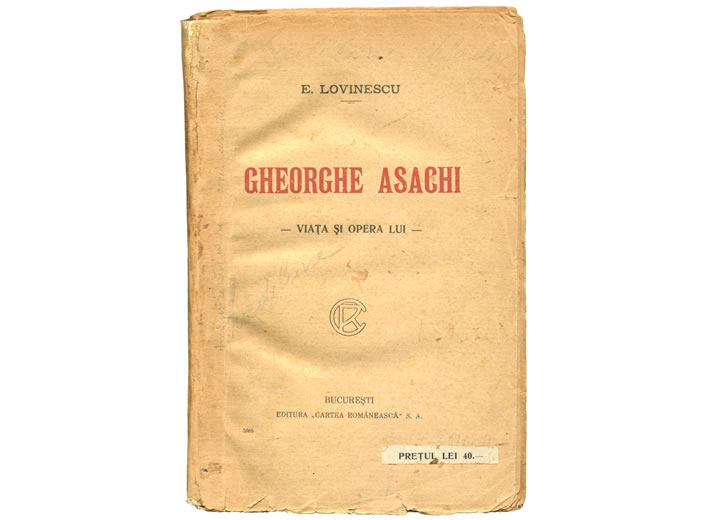

The sources for Gheorghe Asachi's early life and the basic facts about his ancestry are often contradictory. In this section I am following the tale as it is untangled by Eugen Lovinescu (1881–1943) in his book Gheorghe Asachi, Viaţa şi Opera lui 'Gheorghe Asachi, his life and works' (Bucharest 1921).

His father was at that time the Greek Orthodox priest in Herța, Lazăr Asachi. At some point he was transferred to Lviv (a.k.a Lemberg – the Lemberg that is now in western Ukraine, not one of the other Lembergs). On 20th July 1795 he was appointed chaplain of the hospital in Lviv. He would spend about eight years there. In that same year, 1795, he enrolled his two sons, Gheorghe (then seven) and Petru in high school in Lviv, which was then and is now a centre of learning.

Gheorghe studied there (German, Polish and Latin) for nine years from 1795 to 1804, that is, until he was seventeen years old. On completion of his studies he was awarded the title Doctor of Philosophy.

But as we all know, teenage polymaths need to keep busy – no propping up the Student Union bar for them: in parallel to his language studies, Gheorghe studied civil engineering, obtaining his engineer's diploma also in 1804.

Sometime in or shortly before 1803, Gheorghe's father Lazăr had been appointed an archpriest in Jassy. When Gheorghe completed his studies in 1804, therefore, he moved to Jassy to join his father.

I have no information on the progress of Gheorghe's brother Petru during this time, but for the curious we note that he is listed a few years later as a participant in a course in the 'Royal School' given by his brother in 1814-1819. The course, intended for qualified engineers, covered 'theoretical mathematics and the practical application of geodesy and architecture' and was delivered in Romanian – an early example of Gheorghe's encouragement of Romanian as a viable language. The course was a great success and enhanced Asachi's reputation as an outstanding polymath among the Romanian ruling class ('boyars').

After this aside, let us return to Gheorghe Asachi in Jassy in 1804, after the completion of his studies. He did not remain long in Jassy – he fell seriously ill with a fever, unsurprising in the humid continental climate of Jassy, with extremes of heat in summer and cold in winter. We should bear this depressing climate in mind when we are reading Heloise's 'Family Notes'.

His doctor advised him to seek a kinder climate, so on 16th July 1805, in the company of his brother Daniel, he undertook the 20-day coach journey to Vienna (the reverse journey that Heloise would later take). In Vienna the never-weary polymath studied astronomy with the renowned Austrian astronomer Johann Tobias Bürg (1766-1835), just then at the height of his fame.

There is uncertainty about the date of the conclusion of Asachi's time in Vienna. It seems that he spent around three years there, from 1805 to 1809 (or possibly 1808).

Then Asachi departed for Rome and spent his first months deepening his knowledge of Italian and exploring Roman archaeology. After a few months of swotting Italian he wrote a poem in Italian that found great favour in Italian intellectual circles and opened many doors for him there.

Asachi himself dated his time in Rome from 1807 until 1812, but like most dates in his biography, few can be relied upon. According to his own account, he left Vienna on 13th April 1808 and, with many stops in between – Venice, Florence etc. – he arrived in Rome on 11th June. About two months later, on 19th August, he left Rome for Naples, taking in all noteworthy stops in between until he arrived at the foot of Vesuvius on 25th August.

His doings in Rome were full of incident – we are dealing with Gheorghe Asachi after all – but they are not relevant for us here. He left Rome on 22nd June 1812, first went to Milan, then Verona, then Venice, from where he took ship to Constantinople, finally returning to Jassy on 30th August 1812, thus closing the triangle of a long intellectual journey.

He returned to Jassy loaded up with knowledge and was primed to begin what would become his lifelong campaign to bring his country, its neglected language and its people into the modern world.

In Vienna, for example, from about the 1770s onwards, the Hapsburg rulers had taken steps to improve and develop the educational system of their Empire. Their subjects in the old feudal states had to make the transition from agrarian illiterates to becoming people who could read and write and function in the new world being shaped by the industrial revolution. The great rival, protestant Prussia, had a head start and was pulling away from Austria.

In Moldavia, however, on the outskirts of empire, this development began half a century later, pionered by Asachi with the support of his relatively enlighted prince, Mihail Sturdza.

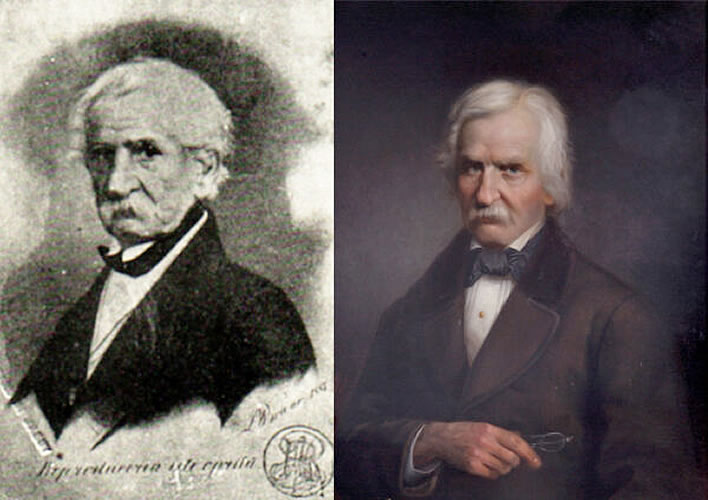

Giovanni Schiavoni (1804-1848), Portrait of Gheorghe Asachi, 1830.

Giovanni Schiavoni was appointed in 1837 as professor of art at the Academia Mihăileană (founded by Gheorghe Asachi). His portrait of Asachi surrounds the sitter with a clutter of symbols representing his many talents. Asachi was not one who cared for baubles, unlike the aristocracy of the time, thus forcing Schiavoni to represent Asachi's achievements as symbolic objects. We are shown a globe, shelves of books, a folder with manuscripts, a quill, a painter's easel, a bust (which some critics consider to be that of an Encyclopédist) and, on the wall, a suggestion of an engraving done by Asachi: Muma lui Ştefan cel Mare refuzând intrarea fiului său în cetatea Neamţ în 1484, 'The mother of Stephen the Great refuses to let her son enter the fortress of Neamţ in 1484' Image: Muzeul Național de Artă al României. A discussion of this image can be found in Gheorghe Macarie, 'Giovanni Schiavoni – Un Pictor Italian La Academia Mihăileană din Iași' in Cercetări Istorice XXVII-XXIX (2008-2010), Iaşi 2011, p. 269-292 (pdf).

Gheorghe Asachi, Muma lui Ştefan cel Mare refuzând intrarea fiului său în cetatea Neamţ în 1484. This is prentice work: Asachi's concept was guided by the Italian neoclassicist artist Felice Giani (1758-1823), whom Asachi got to know during his stay in Italy (1808-1812). Gheorghe could certainly draw, though. Image: Biblioteca Județeană "V.A. Urechia" Galați.

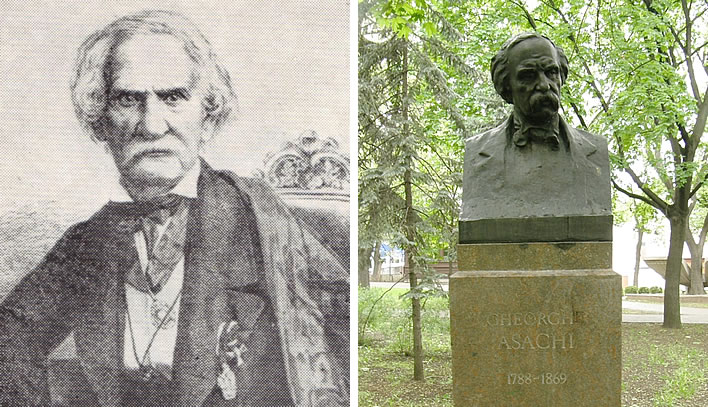

A fine bust of Asachi is in a prominent position in Herța's main park, next to which is the public library which bears his name, as does the street in front of it. Image: 'Prin Herța lui Gheorghe Asachi' in Libertatea Cuvântului.

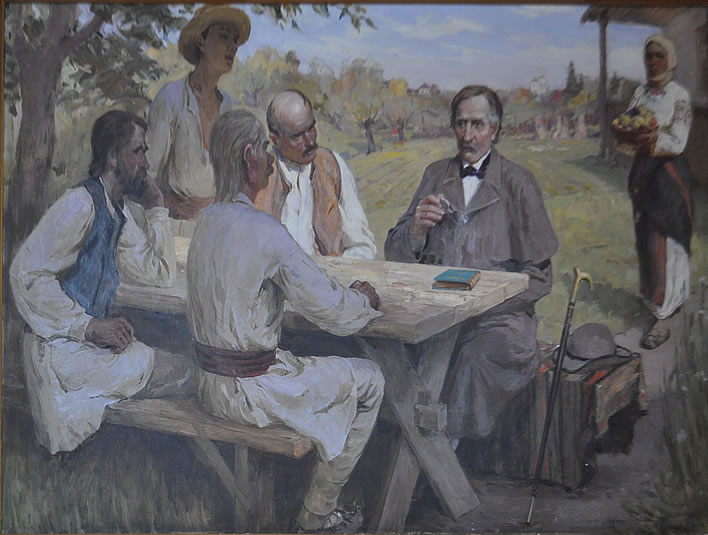

The Public Library 'Gheorghe Asachi' in Herța possesses a painting of Asachi in a discussion with (presumably) Romainian peasants. Despite his intellectual prowess Asachi remained a man of the people at heart. The artist is unknown to me at the moment, but I would guess that it was that other famous resident of Herța, Arthur Verona (1867-1946, in Herța from 1881). Image: 'Prin Herța lui Gheorghe Asachi' in Libertatea Cuvântului.

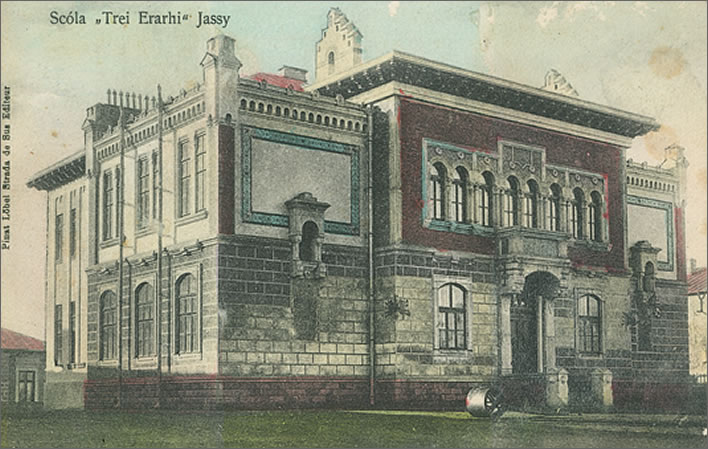

Gheorghe Asachi became for more than 40 years the driving force for educational reform and development in Moldavia/Romania. In March 1827 he was appointed Minister of Public Education, which was the springboard he used to push through his programme for the linguistic, cultural and artistic revival of the country. He increased the number of schools and opened them to disadvantaged children. He worked tirelessly on developing a Romanian national identity through language and art. He didn't hang around: in 1828, only a year into his tenure in office, he laid the foundation stone for the 'Trei Ierarhi' School in Jassy [the Trei Ierarhi are the 'Three Hierarchs' of the Orthodox Church: Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom].

Postcard showing the 'Trei Ierarhi' School in Jassy (ND). Image: Scoala 'Gheorghe Asachi' Iasi.

'Great oaks from little acorns grow': At first the school had only two classes of one year each, In 1830 it introduced a four year programme and then two years later became a public educational institution.

An impressive white marble statue to Gheorghe Asachi in front of the 'Trei Ierarhi' School in Jassy.

The inscription on the front of the plinth is : Primului învăţător, Gheorghe Asachi, şcolile româneşti recunoscătoare, 'To the first teacher, Gheorghe Asachi, from grateful Romanian schools'.

When the statue was unveiled in 1890 the remains of Gheorghe Asachi (†1869) and those of his wife Elena (née Eleonore Teyber, †1877) were brought from their original burial place in Copou and placed in a metal casket under the base of the plinth. Image: Gheorghe Asachi – spiritul enciclopedist care a deschis școlile de fete în Moldova.

A bas-relief on the side of the plinth shows Gheorghe Asachi offering coronals to the prize-winning students from the higher school. In the background is the silhouette of the Trei Ierarhi Church in Jassy). Image: Scoala 'Gheorghe Asachi' Iasi.

After founding the school, Asachi persuaded Prince Mihail Sturdza to found the Academiei Mihăilene (1835), the 'Michaelean Academy'. It offered studies in architecture, engineering, civil engineering, theoretical and experimental physics, higher mathematics, chemistry and chemical technology – just what a nation hauling itself out of its rustic past needed.

There is a second bas-relief on the side of the plinth of Asachi's statue in Jassy. It depicts Asachi presenting his plans for the Academiei Mihăilene (1835) to Prince Mihail Sturdza, the ruler of Moldavia. It offers us an image of the power constellation in Romania at that time: the Metropolitan of the Greek Orthodox Church on the left representing the deep spiritual foundations of Romania; the Prince, sitting at the table, suited and booted, the representative of secular feudal power. He would be deposed a few years later. Image: Scoala 'Gheorghe Asachi' Iasi.

Academia Mihăileană ND Image: Asociaţia Culturală Matricea Românească.

A lot of people have great ideas. Far fewer have the talent of persuading the powers that be to put their great ideas into action. Asachi, seemingly by the aura of his intellect and his powers of argument, made a reality of his vision of a Romanian renaissance. Within about twenty years, by leveraging the great and good of that time in Moldavia, he not only built an education system out of almost nothing, he brought the Romanian language out of its backwater as a purely demotic language and reanimated Romanian culture.

His key supporters were Ioan Sandu Sturdza, the ruler of Moldavia from 1822-1828, whose aim was to free Moldavia from the Greek hegemony and restore the teaching of Romanian, and Mihail Sturdza, who was ruler from 1842 to 1849. Asachi was a prime mover in the Zeitgeist for Romanianisation under these two rulers – the right man, in the right place at the right time, pushing against an open door.

Mihail Sturdza

Asachi not only motivated the powers that be in Moldavia to implement his dream, he was clever enough to step back and let them bask in the glory of their achievments:

The feudal order on the threshold of the Enlightenment, albeit a century behind western Europe: Giovanni Schiavoni's painting of the Ceremony of the Mihăileană Academy (8 November 1837)

8 November was Michaelmas, the name day of St. Michael in the Orthodox Church. The ruler of Moldavia, Mihail Sturdza, chose this public holiday for the ceremony to celebrate the establishment of the Mihăileană Academy. Giovanni Schiavoni, a professor of art at the Academy, documented this ceremony in this monumental (3.5 x 3 metres) painting.

Mihail Sturdza stands in the centre, with the powers that be in the Moldavian princedom ranked in a half circle behind him. The core of the state was an intersection of the Orthodox Church and the feudal nobility, symbolised by Sturdza's hand resting on the Bible held by the Metropolitan Veniamin Costachi. Sturdza's son Dimitrie is next to him. There are consuls from Russia and Prussia, and a collection of personages from the ruling boyar class. Behind them are some professors from the Academy (Alexander Costinescu had not yet joined the Academy) and then the shadowy figures of the lesser aristocrats. Asachi, the brain behind the foundation of the Academy is in there somewhere, but it is clear who the really important people are. Image: Private collection Jean Maisonabe, Bertholène, France. This painting is also discussed in Gheorghe Macarie, op. cit.

Gheorghe Asachi, in his campaign to recover the Romanian language, had begun with his own writings and journalistic productions in that language, had then brought two major Romanian language education institutes into being. Then, in 1837, he was appointed Head of the Moldavian Theatre, which formed another important tool for bringing Romanian back to the status of a living and respectable national language.

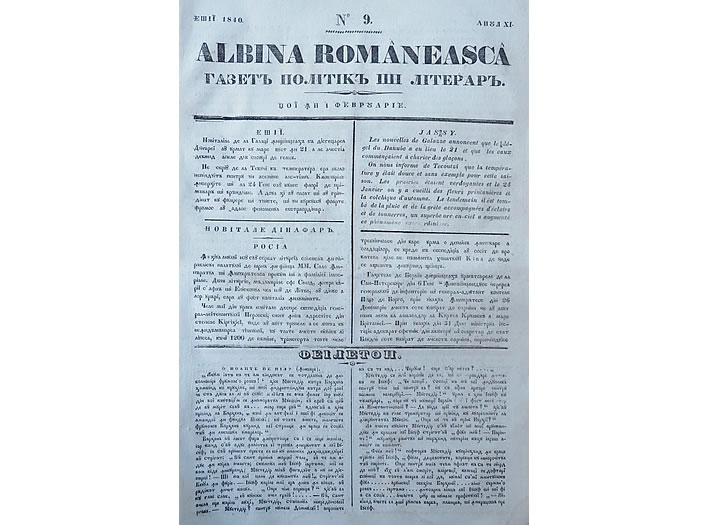

Albina Romaneasca, Coperta Nr. 9, 1-februarie-1840, one of Asachi's influential journal publications in Romanian.

From a frontispiece in a book.

Left: a portrait of Gheorghe Asachi in old age, originally printed in the first edition of his collected short stories c. 1860.

Right: a bust of Gheorghe Asachi in the 'Alley of Classics' in the Stephen the Great park [Grădina Publică 'Ștefan cel Mare'] in central Chisinau, erected in 1958.

Image right: ©Klearchos Kapoutsis, 2008.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!