Ermiona Asachi

Richard Law, UTC 2025-02-01 08:00

Eleanora/Elena's daughter Glicheria [Glyceria] (1821-1900) now becomes the focus of our interest, for with her we are with the person whom Heloise called her 'loyal friend' in her 'Family Notes'.

Ermiona Asachi, Gheorghe Asachi's daughter

'The apple doesn't fall far from the tree', we noted earlier. This is certainly the case with the talented Glicheria/Ermiona. [NB: After she moved to Paris Ermiona's Romanian name morphed into the French version Hermione. We shall use whichever is appropriate in the context.]

She was born on 16th December 1821. Thus, referring to Heloise's biography for a moment, Ermiona was almost seventeen in 1838, when the 28 year-old Heloise (born 9th March 1810) arrived in Jassy as Costinescu's bride.

Hermione Asachi in a daguerreotype taken somewhere between 1848 and 1850. She would have been in her late twenties. The photograph is mounted in a wooden rectangular case covered with green velvet, 12 x 10 x 1.2 cm, protected inside by a white silk cushion. Object: Engravings Cabinet, Romanian Academy Library; Romania Cabinetul de Stampe, Biblioteca academiei Romane; Web image daguerreobase.org.

Ermione inherited her mother's musical gifts, became an accomplished pianist, harpist and singer. If she really was Asachi's daughter it seems that she also inherited his facility with languages, in her case six languages (so it is said) including her Romanian mother tongue. As a result of her talents and intelligence she helped her father as an assistent and secretary. As a young girl she performed at the Asachis' soirées before the cultural elite of Jassy and Moldavia.

During her time in Romania her literary talents were devoted to translations of works in French, German and Italian into Romanian. Let's see if the works she chose to translate tell us anything about her.

Emile Deschamps, René-Paul et Paul-René

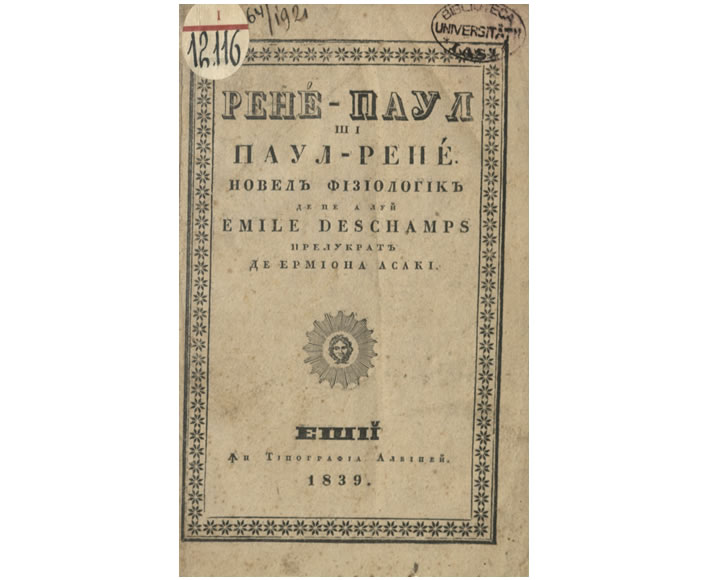

The first of her translations to be published was a translation of a short story by Emile Deschamps (1791-1871), friend of Alexandre Dumas, Balzac etc. from a set he called Contes physiologiques. The story is entitled René-Paul et Paul-René, which became René-Paul şi Paul-René : novelă fiziologică (1839).

Deschamps wrote in the spirit of the Romantic/Gothic spookery popular at the time, most famously in the works of E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776-1822).

René-Paul and Paul-René are born as conjoined twins, two bodies but one soul. The tale ends badly when one of the now separated pair, Paul-René, shoots himself after his rejection by Dona Elvira, assuming that in doing so he was nobly clearing the way for his brother to marry her. But, as a result of some Romantic/Gothic woo-woo, in doing so his brother (two bodies but a single soul, remember) died too. The suicide, Paul-René, is thus a murderer with the best intentions.

Asachi, Ermiona (1821-1900), René-Paul şi Paul-René : novelă fiziologică (1839) translated from the French of Émile Deschamps, René-Paul et Paul-René. The French original is in Volume III of Deschamp's Oeuvres complètes, which can be viewed or downloaded as a PDF from the Internet Archive.

The Romanian text is printed in the cyrillic alphabet, which was only just starting to be replaced by the roman alphabet for Romanian. The transition would not be completed until about 1860. Asachi favoured the use of the roman alphabet – Romanian was, after all, a romance language that had suffered in the old days under Russian and Greek masters. Image: © 2025 'Mihai Eminescu' Central University Library Iasi

Caroline Pichler, Ruth

1839 was a busy year for Ermiona. She also published a translation of Caroline Pichler's (1769-1843) Ruth. Ein biblisches Gemälde in drey Idyllen (1805).

Karoline Pichler, Ruth. Ein biblisches Gemälde in drey Idyllen, 1805.

Pichler was not only very popular at the time but she was also regarded as a relatively safe pair of literary hands during the oppressive and very intrusive censorship of the Austrian Empire. We have mentioned her a number of times on this website, most recently here.

The biblical tale of the faithful Ruth has been a rich source of moralising down the ages, although the virtues extolled depend largely on the taste of the teller.

Sacred History for Moldavian-Romanian Youth

There followed, in 1841, Ermiona's translation (with additions) Istoria sfântă pentru tinerimea moldo-română, 'Sacred History for Moldavian-Romanian Youth'. Both this patriotic and moralistic work and Pichler's Ruth became a required text in Romanian schools.

Istoria sfântă pentru tinerimea moldo-română (Ediţia a 2-a/1846 edition). NB: The text is in the transitional language (a mixture of cyrillic and roman characters) that was used during the changeover from cyrillic to the roman alphabet (1830-1860). Image: © 2025 'Mihai Eminescu' Central University Library Iasi.

Silvio Pellico, I doveri degli uomini

Then, in 1843, she translated a work by the Italian revolutionary and carbonaro Silvio Pellico: I doveri degli uomini, 'Of the duties of men' (1834), Despre îndatoririle oamenilor.

Silvio Pellico, I doveri degli uomini (1834).

On the evidence of the book that brought him fame, Le mie prigioni (1832), your author has always considered him to be an untrustworthy fantasist. The present work adds nothing to his worth: it's a strange, moralising work, consisting wholly of trite, pious assertions with little reasoning behind them – not worth reading, let alone translating. A particular feature is its elevation of women in many respects to an almost courtly ideal – certainly an advance on their general status at the time. Perhaps that is what Ermiona saw in it, but we have to question her judgement in investing a lot of time in Pellico's waffle.

The common thread through all these translations is their edifying, moralistic message. Even René-Paul et Paul-René is moralistic in a spooky way.

She chose these texts and thus it seems probable that they accurately reflect her own beliefs and faith in the education of the masses. In this she is in tune with a Zeitgeist of the first half of the 19th century. In Switzerland writers such as Jeremias Gotthelf (= Albert Bitzius, 1797-1854) and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) were propagandizing the rewards of the good life well lived, but almost every European country had their own equivalents.

Alexandru D. Moruzi

One incident, however, shows that Ermiona was no respecter of social conventions, quite the wild child, in fact. In 1835, when she was 13, she fell in love with Alexandru D. Moruzi (1815-1878) from a very prominent Moldavian family. The bewitched young man ended up living with Ermiona in the Asachis' house. A visitor to one of the Asachis' salons described the young man as 'tall, blond(?) and handsome'.

Alexandru D. Moruzi, ND.

It appears that the immediate parents on both sides were unfazed with this situation, but other members of the Moruzi clan were scandalised and insisted that the two young people, if they wouldn't change their domestic arrangements, had to be married. The pair were married in 1836. The fruit of their union, baby Georges Moruzi, arrived in 1839.

We could leave the young love between Ermiona Asachi and Alexandru D. Moruzi on that prurient snigger and move on, but Alexandru is not just some young, lovestruck chap – he is a remarkable personality in his own right.

He was born in Constantinople on 30th March 1815. In 1829 he and his family moved to Pechea (in Galați County) about 200 km due south of Jassy (Iași). The periods in his life between then and 1835, when he and Ermiona were allianced and from then on to 1845, when she left for Paris, are scarcely documented. Apart from his extremely noble parentage, we know next to nothing about him from this time.

Yet with the 1848 Revolution in Moldavia he suddenly becomes a deserving focus of our attention. He took an active part in the revolution, was arrested in Jassy along with other leaders of the revolution and sent into exile. The captain of the ship taking them into exile was bribed, the crew were drunk, so that the passengers were able to disembark a little further downstream.

After numerous adventures and the establishment of a new government in 1856 he was appointed the following year as 'Extraordinary Commissioner' in the city of Galați, a port city on the righthand bank of the Danube. We don't need to go into his remarkable political career after that point, which included many infrastructure projects that brought the region into the modern age. He died on 6 February 1878 in Galați.

What is more interesting for us is his intellectual development as a liberal (in the classical sense) economist, in itself perhaps surprising for one with such aristocratic blood in his veins. He wrote extensively (in French) advocating individual and commercial freedom and the inviolability of property rights. We just know that Moruzi was on the right lines when we learn that in 1947 the communists dismantled his statue and melted it down.

Oscar Späthe (1874-1944), bronze bust of Alexandru Moruzi (1936). Image: adevarul.ro.

He saw that Romania was an agrarian backwater, but argued that its future did not lie in mindless industrialisation, which he thought would never succeed – the country was unatttractive to capital and could never survive price competition with other nations. He argued that free trade and expanded grain production (well suited to Romanian conditions) would bring prosperity and that Romania's location, on the trading axis of the East and the West, offered great opportunities.

Alexandru Moruzi's great work, Progrès et liberté (1861). A Romanian version (2024) is available from the Institutul Ludwig von Mises – România.

We realise now that Ermiona's choice of her first husband may have had more to it than juvenile passion. Moruzi had been thoroughly educated and was probably an intellectual match for her.

Alexandru D. Moruzi in later life, ND.

They divorced in 1849, the year after the revolutions in France and Romania – perhaps Alexandru was on the boat into exile – and three years later she married Edgar Quinet.

In contrast to that pointlessness, action man Alexandru realised numerous great and practical projects in Galați and got through three further wives and produced five more children.

Edgar Quinet

Ermiona looked after Georges with the help of the Moruzis. She took him with her to Paris when she emigrated there in 1845. She wanted to savour the cultural life there, whilst Georges could get a good education. Georges fell ill and died, 17 years old, on 14th March 1856 in Brussels.

In 1852 she married the French writer and revolutionary Edgar Quinet (1803-1875), whose wife had died the year before. As we might imagine, the role of a revolutionary troublemaker suited her down to the ground.

Sébastien-Melchior Cornu, Portrait d'Edgar Quinet (1803-1875), c. 1835. Image: Musée Carnavalet – Portrait d'Edgar Quinet (1803-1875), littérateur et homme politique.

Quinet's scattergun iconoclasm in his Collège de France lectures that she attended must have appealed to her in much the same way that Pellico's random jottings did. Quinet was eventually ejected from the Collège de France, his lectures having become just rabble-rousing rants.

Ermiona, the wild-child, supported the Revolution of 1848 along with Quinet, who was active in the resistance. Her father – more used to dealing with the aristocracy – could not support the 1848 uprising. It has been suggested that she stayed in France after 1848 and did not return to Romania because of that. Who knows?

After the collapse of the 1848 revolution in the coup d’etat of 2nd December 1851 and the subsequent restoration of monarchical power, Quinet, Ermiona and son Alexandru went into exile first in Belgium (where Alexandru died) and then Switzerland. They endured 19 years of exile before the fall of the Second Empire on 4th September 1870 made it safe for them to return to Paris.

Edgar Quinet through the years: Top left, représentant, Assemblée nationale, 1848. The combover begins: top right, ND; bottom-left, c.1860; bottom-right, c. 1870.

Obedient to her husband's wish to 'save his thoughts from the shipwreck', she spent the years until her death in 1900 editing, translating and publishing Quinet's windbaggery and her own commentaries thereupon, even after his death in 1875.

We humans are supposedly free agents, allegedly with at least some degree of free will, but it is still a great pity that such an intelligent and energetic woman invested so much effort in preserving Quinet's ramblings and, before that, Pellico's nonsense. A few paragraphs from the 'loyal friend' about Heloise would have been much more interesting.

On the title pages of her writings, even late and quite autonomous pieces such as her essay De Paris à Edimbourg (1898, 327 pages!), which was a search for 'culture' in Scotland, written two years before her death and twenty-three years after Edgar Quinet had died, the author is given as 'Mme Edgar Quinet'. On her tomb, she styled herself simply as Widow Edgar Quinet – even her corpse wasn't her own.

There are many examples of her obsession with publishing and sanctifying every bit of Quinet's literary relics. For example, in 1877, two years after Quinet's death, 'Veuve Edgar Quinet' published the anodyne letters he had written to his mother ('Ma chère et tendre mère') between 1826 and 1845. We need Dr Freud to disentangle that complex.

Being needed, giving love

What is at the root of this submissiveness to Quinet, her total obliteration of self in his service? Some of her contempories were also shocked by the extent of her self-degradation. No feminist icon here, just a washerwoman for Quinet's smalls. French critics were baffled. If it wasn't sex – no one ever detected any trace of that, by the way – what was it?

'Giving love seems to be a deep need of hers' we wrote of Heloise, who singled out her son Alexander as the needy one who would be the recipient of her unconditional love.

Perhaps we can say the same about Ermiona, who had her own needy one in Edgar Quinet. He was persecuted for years: thrown out of the Collège de France, thrown out of Parliament, escaped into 19 years of exile, an exile in which her own son Alexandru Moruzi died in the flower of youth.

When the Quinets finally made it back to Paris, the world of 1848 had gone. It had given way to the catastrophe of 1870 and the deep humiliation of the French at the hands of the Germans. In this new world, Quinet is an irrelevance.

The need to be needed is the simplest way we can explain Ermiona's pious and slavish devotion to her needy husband, which continued long after his death and to the very end of her own life and even to the grave.

Perhaps both Heloise and Ermiona at heart desperately needed to be needed. Who knows?

The Quinet grave in the Cimetière du Montparnasse, Paris.

The inscription on the left panel reads: V[eu]ve EDGAR QUINET / 16 DECEMBRE 1821 — 9 DECEMBRE 1900 / REUNIS POUR L'ETERNITE ET DANS LA VERITE [It is of note that Ermiona effaces her own, Asachi existence completely, as she did in most(?) of her publications, replacing her name with the formula Widow Edgar Quinet, yet another astonishing submission to her master, Quinet]

The inscription on the right panel reads: EDGAR QUINET / 17 FEVRIER 1803 — 27 MARS 1875 / VIVRE[,] MOURIR[,] POUR REVIVRE

The inscription is a quotation from L'Esprit nouveau, Dentu, Paris, 1875: Le sort de l'univers, avec tout ce qui vit et respire, les mondes eux-mêmes se dissoudront pour renaître. … Non, j'accepterai le sort commun à tous les êtres, vivre, mourir, pour revivre. (The fate of the universe, with everything that lives and breathes, the worlds themselves will dissolve in order to be reborn. No, I will accept the fate common to all beings, to live, to die, in order to live again.) Image: Wikipedia, user Selbymay.

Heloise and Ermiona

For a tantalising moment in the 'Family Notes', Heloise and Ermiona share the stage. In Heloise's account of the birth of her son Emil on 12th March 1844 she states that 'on 19th March my loyal friend Hermiona Asachi baptised him'. In her memoir, Heloise mentions people outside her immediate family circle only thrice and in the briefest terms at that.

We note that, at the moment of that entry, Heloise was 34 and her 'loyal friend' Hermiona was 23. Now we know a little about each of the two women, can we reconstruct their shared presence at this moment?

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!