Il Hobbit — why?

Richard Law, UTC 2025-07-15 12:14 Updated on UTC 2025-08-11

Following on from my recent review of Not Soliva's translation of J.R.R. Tolkien's children's story The Hobbit into Romansh, one question lingers: what purpose does a translation of the The Hobbit into Romansh serve? What need does it fulfil?

There may be a handful of speakers of Romansh squatting in huts somewhere in the mountains who can't speak Swiss-German or High-German, but the last one of those in my village was born in 1910 and passed away forty or so years ago. Nowadays, all speakers of any of the five idioms of Romansh also speak German. In village meetings it only needs one non-Romansh speaker to turn up for everyone to switch to Swiss-German.

All children in Romansh-speaking locations at some point learn German, so that when they grow up they can flee the homestead for the towns and cities of anywhere else but Graubünden, get higher education or an apprenticeship and a well paid job in civilisation.

I was in hospital in Chur, the capital of canton Graubünden, for a few weeks last year. Of all the scores of staff with whom I had contact, only two could speak some idiom of Romansh. It is true that the Swiss health service, much like the ancient civilisations, largely runs on foreign labour, so this observation should really not be surprising. Bottom line: Despite the tremendous nostalgic attraction of the mother-tongue for those who have it, in everyday life Romansh is merely an optional extra.

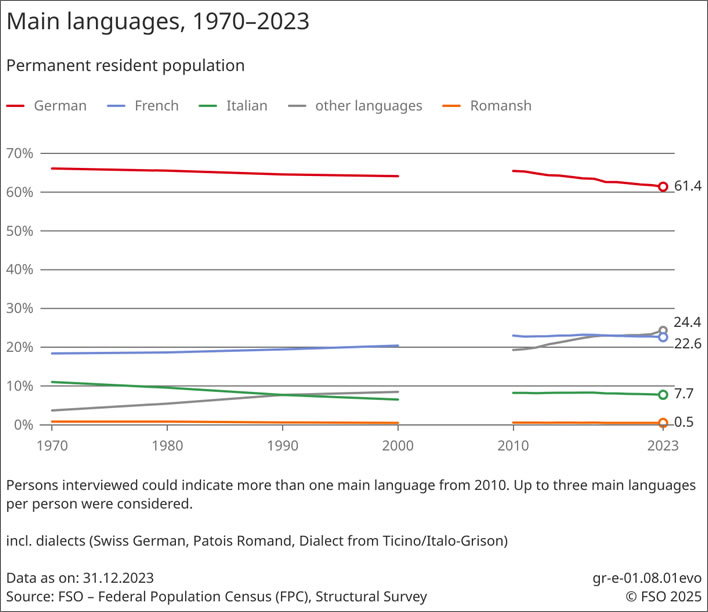

Consider this chart from the Swiss Federal Office for Statistics. The number of Romansh speakers (all five idioms taken together) is around 0.5% of the population (the orange line bumping along the bottom of the chart). [Note that all the charts below relate to people who are 15 years old or over. The children in Romansh-speaking areas of Graubünden will all learn Romansh and usually speak it among themselves for a while.

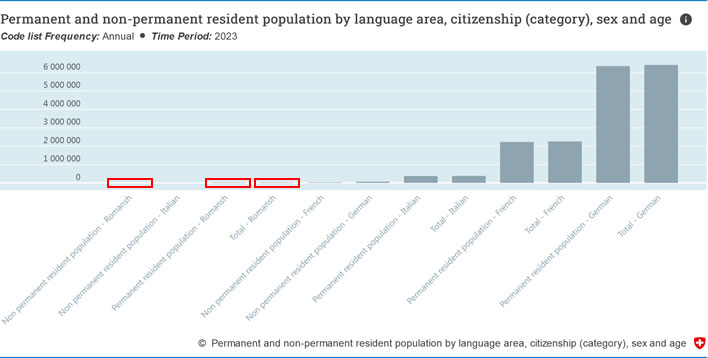

Here's another way of looking at it. The totals for Romansh speakers are boxed in red – they are so small that they are barely visible.

Here are the numbers from the chart:

| Total | Permanent residents |

Non-permanent residents | |

| German | 6'409'262 | 6'344'274 | 64'988 |

| French | 2'252'187 | 2'224'134 | 28'053 |

| Italian | 376'540 | 373'158 | 3'382 |

| Romansh | 21'277 | 20'692 | 585 |

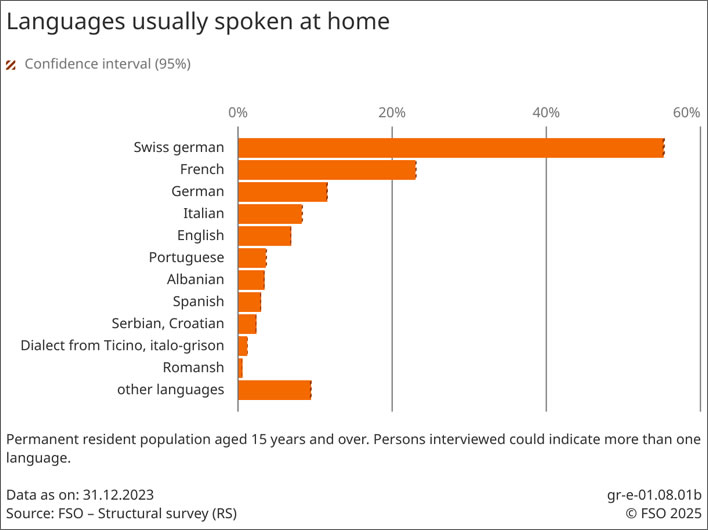

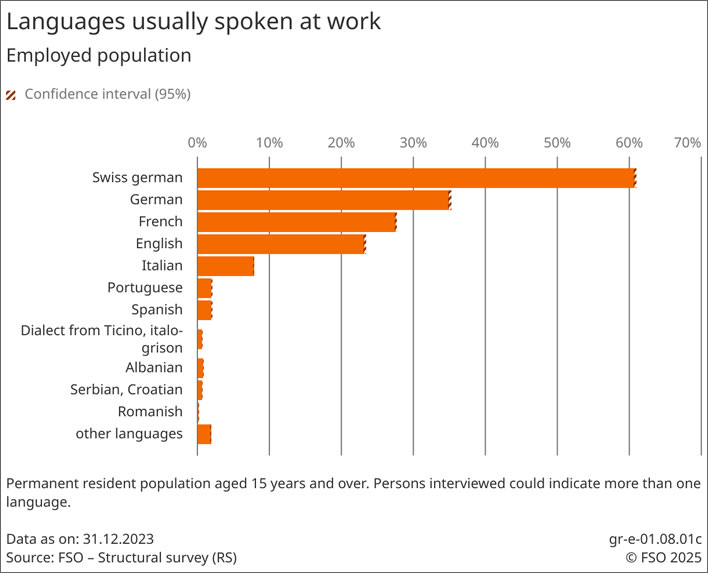

Here are two more representations, a little bit more nuanced. As with all our figures so far, the numbers for speakers of Romansh are so small that they are almost rounding errors and barely there on the charts:

These last two charts make clear that not only is the proportion of Romansh speakers tiny, it is numerically overwhelmed by the languages brought by the new arrivals over the last half-century – not to mention the category 'other'.

The daily newspaper that claims to represent all five idioms of Romansh is La Quotidiana. It currently has a circulation of around 4'000, which seems credible for a readership population of 20'692 permanent residents. We are not counting 'households' here, of course.

We can put the number 20'692 into a simple context. It is the population of a smallish town. In Switzerland we could take Aarau [AG, 21,726] or Baden [AG, 22,584]; in Great Britain Buxton [Derbyshire, 20,050] or Workington [Cumbria, 21,275]; in Germany Günzburg [Bavaria, 22,000] or Northeim [Niedersachsen, 19,180] and so on.

Remember that the Federal Office for Statistics does not count people under 15 in this figure, but this is the population of the adult tribe, the romontschadad or Rumantschia as it is known. We repeat: all of these people speak Swiss German (or German) fluently.

If they want to read The Hobbit, they can chose from a number of cheap paperback editions in German – cheap, because of economies of scale: there are around 82 million speakers of German in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, compared with 20 thousand Romansh speakers – that is nearly four thousand times as many.

As the charts above make clear, Romansh is a language that is on a life-support system. It is kept going by the steady flow of taxpayer and shakedown cash down the infusion tubes. Despite this, the language remains in a vegetative state: the number of speakers of the language is never going to increase and other languages are vastly more attractive and useful. Romansh as a mother-tongue is adequate for the needs of the playground but sooner rather than later fades into irrelevance when confronted by the massive dominance of German. All indicators (for example brain death) say it is time to switch the machine off.

In a Bündner village I lived in a few years ago, in a misguided search for literature in Romansh (the idiom there was Surmiran) I called in at the local library to see what they had. The extensive shelves over two floors were stuffed with page-turner novels (in German, some Italian, some English), non-fiction concerning garden herbs, tai chi, cookery (more Jamie Oliver than was good for them) and life improvement regimes (almost all in German). I couldn't find the Romansh section, but the librarian was kind enough to show me a single shelf at the side, which was empty apart from about 50 cm of books, copies of most of them were already on my shelves at home. That's it? That's it, she said, as though the response was completely obvious. Why is this English idiot looking for books in Romansh when there is so much Jamie to read?

The library holds play and storytelling sessions in Romansh for children. But what do they read when they grow up?

From the very long list of questions we cannot answer, let us take two: What proportion of these 20'692 Romansh speakers read books? What proportion buy books? Your guess is as good as mine. It would surprise me if it was greater than, say, five percent. The bookshops I know stock mainly books for tourists – the passing trade as it used to be called.

Over the last century, the bearers of the Romansh language were tiny local newspapers put together by dedicated amateurs. The content had a local focus and was written in the relevant idiom of the language. The publishing of individual books was limited; instead, annual compendiums were more economically viable. There was, for example, Igl Ischi, 'The Maple Tree' (1897-2005), which was, to its great credit, largely funded by local advertising. A more literary production was Nies Tschespet, 'Our Plot of Ground/our turf' (1891-2003). In addition, the Società Retorumantscha published its Annalas (1886-) usually with quite heavyweight contributions. Two annual 'calendars' were a little less highbrow: the Calender Romontsch (1860-), intended for the Catholic speakers of Sursilvan and Per mintga gi (1922-), 'For every day' for the Protestants.

Of course, the business model behind these annnuals left no space for the self-promotion of the scribbler-egos that the publication of single-author books enabled.

So the publishing business – if business it can be called on this low customer potential – has a problem that the publishers of other, monolingual countries do not have. How do they solve it? Like this:

By scooping up public money wherever it is piled, by shaking down prosperous companies and by pulling strings wherever they dangle. In the case of the sponsorship page for Il Hobbit shown here, we find some well-heeled private persons, the odd trust fund, five municipalities (Disentis, Tujetsch, Lumnezia, Sagogn and Sumvitg), the local electricity utility, the canton of Graubünden, the Abbey school of Disentis and the usual suspects stuffed with public money to spend on everything Romansh.

Crowdfunding on the website lokalhelden.ch brought in 21'355 CHF from 237 donors (2'000 CHF of which came from the Raiffeisenbank, which supports the website). The total cost of the project is stated there to be 65'000 CHF. We might fairly assume that publication proceeded when most or all of the costs were covered by the various shakedown sponsors, leaving the income from book sales (at 35 CHF per copy) to flow somewhere not clearly defined.

If you were wanting to publish a book in German or English, your argument would be in essence: this is an interesting and desirable book and a lot of people will buy it and we will become rich. On lokalhelden.ch, Leander Etter, the student initiator of the project, justifies it as follows:

- The project adds visibility to the Romansh language, since it is a book that is known outside Romansh culture.

[Das Projekt verleiht der romanischen Sprache Sichtbarkeit, weil es um ein Buch geht, dass auch ausserhalb des romanischen Kulturraums bekannt ist.] - The project brings life to the Romanisch literary scene and encourages writers to translate further works from world literature.

[Das Projekt belebt die romanische Literaturszene und ermutigt die Literaturschaffenden, weitere Werke aus der Weltliteratur ins Romanische zu übersetzen.] - The project shows that the Romansh language is living and young and involved people put themselves out in the cause of its retention.

[Das Projekt zeigt auf, dass die romanische Sprache lebendig ist und junge und engagierte Leute sich für deren Erhalt einsetzen.]

None of these three statements makes any sense. None of them answers our question 'why publish The Hobbit in Romansh, when all the speakers of that language could read it in German?'. One statement is left out and it is the only one that matters but it is not true and clearly counts for nothing in this project: 'A lot of people will want to read it'.

The three arguments given above are really a tacit admission of the obvious. In a language that has scarcely a thousand readers of books, say, the gene pool as it were for people who write Romansh in any creative way must be even smaller. Where are all these creative people who will be encouraged to translate literary works into Romansh?

Since everyone can already read German it makes no sense to translate works from German, which effectively means that the works translated will come from English – many of which will have already been translated into German. Where are all these creative people writing in this 'living' language? On a personal note, the response to my offer to translate James Joyce's Finnegans Wake into Sursilvan seems to have been lost in the post.

If the publishers really wanted to distribute Il Hobbit (ostensibly a children's book) among Romansh-speaking children, they would have surely produced an affordable paperback that parents would buy without hesitation (price point e.g. 15 CHF) and that kids can carry around and read on the bus. Instead we have a deluxe hardback doorstop with dustwrapper and placeholder ribbon which contains all Tolkien's drawings and needed a team of graphic designers to construct it. No one is surprised that it costs 35 CHF, despite all the free money thrown at it. From an aside on the crowdfunding site it also appears that Harper-Collins, the owners of The Hobbit, showed no mercy in slicing out their pound of copyright flesh.

Oh, I nearly forgot. The website lokalhelden.ch offers its content in German, French and Italian. Just not in Romansh. In signur Etter's motivating speech to donors on video he speaks in Swiss-German, not Romansh. So much for the 'living' language. Ironic, indeed, but, hey, no one is foolish enough to think that enough Romansh-speakers will dig into their pockets for this shakedown scheme.

Update 30.07.2025

A couple of weeks ago the supermarket in our next big town set up a table of cheap paperbacks, perhaps a hundred or so – something for their customers to read while working on their tans poolside or beachside, or to help pass the long, slow hours in airports and aeroplanes.

A not very thorough riffle through the books failed to turn up one Romansh title. They were almost all in German, with a few English works.

My knowledge of works in Romansh is limited, but on the way home I was trying to think of some book that I would take with me to help numb the tedium of foreign travel. So far, two weeks later, nothing has come to mind. This is a dead language, no doubt about it.

Update 11.08.2025

When I began my studies at the university I was surprised to see that 'Romansh Literature' was not an academic subject, although 'Romansh Language' cropped up here and there in the curriculum. It rapidly became clear that this situation was not a result of institutional contempt or a professorial private contempt for minority literature. 'Romansh Literature' was (and is now) as good as non-existent.

Als ich mein Studium an der Universität begann, habe ich mit Verwunderung festgestellt, dass «rätoromanische Literatur-wissenschaft» kein in Studienordnungen vorgesehenes akademisches Fach war, während doch «rätoromanische Sprachwissenschaft» da und dort im Lehrplan zu finden war. Nun liess sich schnell ermitteln, dass diese Situation nicht institutioneile Verachtung oder persönliche Geringschätzung von Professoren für Minderheitenliteratur zu bedeuten hatte. «Rätoromanische Literaturwissenschaft» war (und ist bis heute) so gut wie nichtexistent. Wie kam es dazu?

The number of Romansh who concern themselves professionally with literature can be counted on five fingers. Thus the critical insight in existing sources and texts is the reserve of a tiny group. Penetration into this group from outside, even for an enthusiastic foreign language researcher was tedious and certainly only profitable after excessive efforts. […] Romansh literature was not comparable with that of Provencal or Catalan literature in either richness and significance.

Die Anzahl der Rätoromanen, die sich berufsmässig um Literatur kümmern, ist an den fünf Fingern abzuzählen. So blieb die kritische Einsicht in vorhandene Quellen und Texte einer winzigen Gruppe Vorbehalten. Von aussen her einzudringen war selbst für einen begeisterten fremdsprachigen Wissenschaftler mühsam und sicherlich nur nach übermässiger Anstrengung lohnend. […] Den Vergleich mit provenzalischer oder katalanischer Literatur hielt die rätoromanische weder an Reichtum noch an Bedeutung aus.

Iso Camartin, Rätoromansiche Gegenwartliteratur in Graubünden, Desertina Verlag, Disentis, 1976.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!