Kipling's Just So Stories

Richard Law, UTC 2025-08-10 12:04 Updated on UTC 2025-08-31

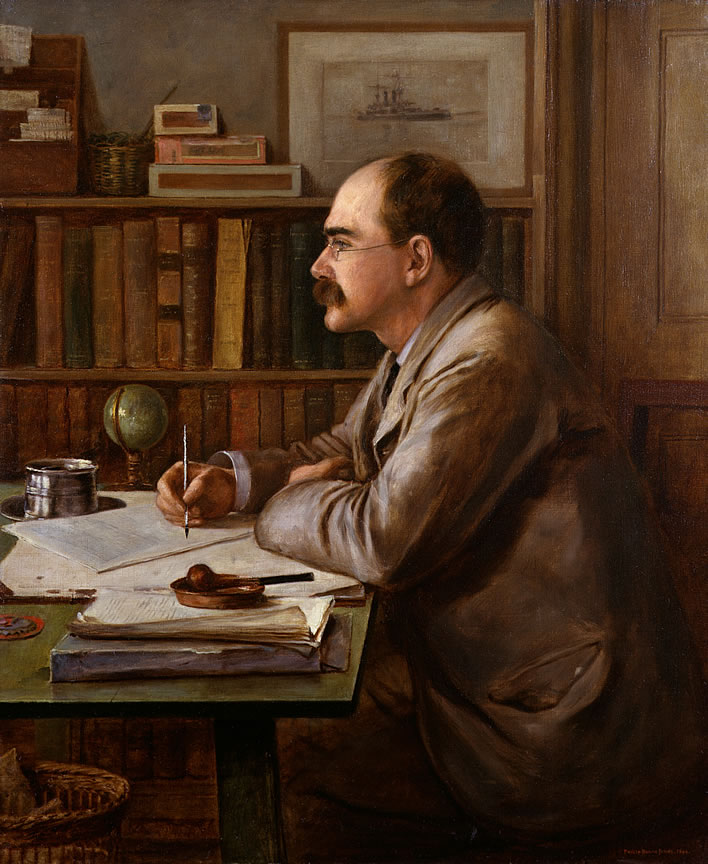

Sir Philip Burne-Jones, Rudyard Kipling (in his house The Elms, in Rottingdean). Painted in 1899, the year of the Rudyard and Carrie's great disaster. Image: ©National Portrait Gallery, London

Last month, following a hint from reader djc, we took a deepish dive into the use of the epithet 'Best Beloved' that so characterises the oral narrative style of Kipling's Just So Stories.

Front cover of an edition of Kipling's Just So Stories. Image: ©National Trust / David Presswell and Anne Chapman

Our dive focussed on the first story in the collection 'How the Whale Got His Throat'.

That was not so much a dive as a toe dipped cautiously into the water. The Just So Stories are an astonishing piece of writing with many interesting aspects. In order to keep focus on the task in hand I had to push many questions and conundrums aside. I treated 'How the Whale Got His Throat' exegetically just to give the reader a flavour of the stories and fill in some of the less obvious things that might be missed in a reading.

Let's try to lift ourselves out of the exegetical swamp and see if we can take a more topdown, structural view of the Just So Stories.

The epithet 'Best Beloved'

In the previous article we looked in detail at Kipling's use of the epithet 'Best Beloved' in the whale story. How is it used in the rest of the collection?

Consider this table. It lists the use of the term 'Best Beloved' in the twelve stories of the 1902 edition, the first book edition of the collected stories. [I have excluded 'The Tabu Tale' from this list and from the subsequent discussion. It was first published in 1903, after the 1902 first proper edition. Kipling himself excluded it from all later editions of the Just So Stories.]

| Story title | Qty 'BB' | Words | 1st pub. |

| How the Whale Got His Throat | 3x | 1'423 | SNM 12.1897 |

| How the Camel Got His Hump | 0x | 1'454 | SNM 01.1898 |

| How the Rhinoceros Got His Skin | 0x | 1'300 | SNM 02.1898 |

| How the Leopard Got His Spots | 5x | 2'416 | LHJ 10.1901 |

| The Elephant’s Child | 7x | 2'845 | LHJ 04.1900 |

| The Singsong of Old Man Kangaroo | 1x † | 1'494 | LHJ 06.1900 |

| The Beginning of the Armadillos | 6x | 3'001 | LHJ 05.1900 |

| How the First Letter Was Written | 7x | 3'519 | LHJ 12.1901 |

| How the Alphabet Was Made | 2x | 4'136 | JSS 1902 |

| The Crab That Played with the Sea | 7x | 4'166 | CM 08.1902 |

| The Cat That Walked by Himself | 7x | 4'450 | LHJ 07.1902 |

| The Butterfly That Stamped | 2x ‡ | 3'836 | LHJ 10.1902 |

–Qty BB = quantity of 'Best Beloved's

–Words = Word count (text, poems and captions)

– First published, LHJ=Ladies' Home Journal, SNM=St. Nicholas Magazine, CM=Collier's Magazine, JSS Just So Stories.

–† = 1x 'O Beloved of mine'

–‡ = +1x Suleiman-bin-Daoud’s Very Best Beloved

Yes, I really am quite a dull person who likes to count things.

Firstly, let's just note how the stories grew in length: the first three are all under 1'500 words; the next four, with one exception, over 2'000 words; the next five hover around 4'000 words – a sign, perhaps, of a writer warming to his theme. Who knows? Let's leave it at that.

But now let's look at the 'Best Beloved' occurrences. The two stories marked in yellow in the table, 'How the Camel Got His Hump' and 'How the Rhinoceros Got His Skin' are the only stories in which Kipling doesn't use the 'Best Beloved' epithet or anything comparable to it, whereas the other ten stories all use this epithet or some variant of it, in some of them quite intensively (four stories each use it seven times).

Why are these two stories exceptions to such a firmly established convention? Doesn't it strike you as odd that in these two stories there is no trace of the narrative method that is present in all the other stories, sometimes massively so?

And even odder, that Kipling starts the collection off with the story 'How the Whale Got his Throat', which is festooned with 'Best Beloved', then abandons the epithet for the duration of the next two stories, then picks it up again for the remainder of the collection? We don't expect these creative types to be bank clerks (unless they are T.S. Eliot, that is) but a little bit of consistency would be nice.

In the search for an answer to these oddities let's begin by taking a look at the creation and publishing history of the Just So Stories.

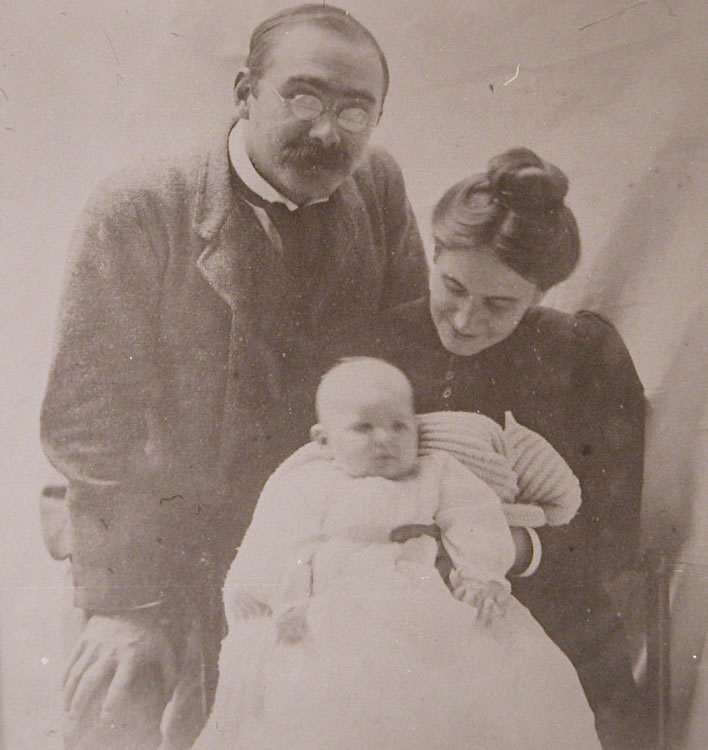

Rudyard Kipling with his wife Caroline and baby daughter Josephine in Vermont, probably in 1893. Image: ©National Trust / Charles Thomas

The genesis of the Just So Stories

For the answer to these problems, or at least the beginnings of an answer, I really should make my way to the Kipling archive in Sussex University in Brighton. And, for the things they don't have there, take a trip to the Berg Collection of English and American Literature in New York.

One day perhaps, but that is not feasible for me at the moment, so I am flying blind in most of what follows. Perhaps some day a keen young person will spend some time messing about in these two bleepholes and then set me right if I have erred.

If I don't have the manuscript history to help me recreate the compositional history, then I can only follow the publication history.

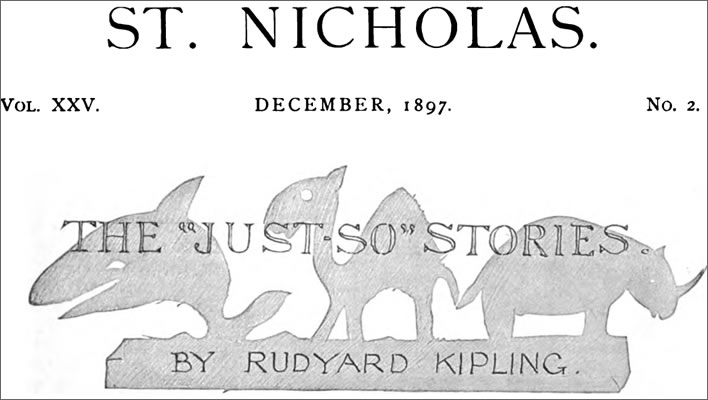

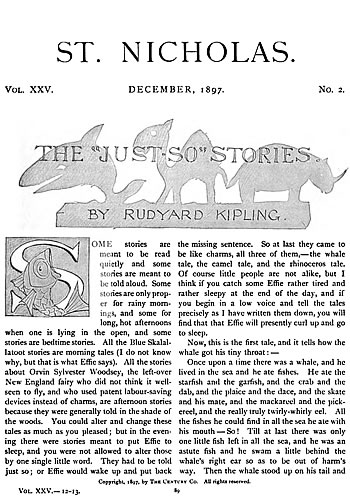

In the beginning, in this case 1879, three stories by Kipling were printed, grouped together under the rubric 'Just So Stories', in the St. Nicholas Magazine, Volume XXV, No. 2, December 1897. This magazine was aimed at children, young and old, black and white and offered good 'educational' writing and quality illustrations. The Just So Stories were: 'How the Whale Got his Tiny Throat', 'How the Camel Got His Hump' and 'How the Rhinoceros Got His Wrinkly Skin'.

At that time the rubric 'Just So Stories' only contained three stories and was presented as such: the illustration for the main title includes only images of the protagonists of the three stories: the whale, the camel and the rhinoceros.

Furthermore, the introduction to the last of the three stories, 'How the Rhinoceros Got His Wrinkly Skin', tells us explicitly: 'Now this is the last tale…'.

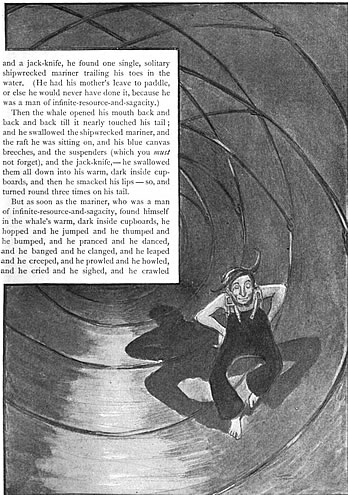

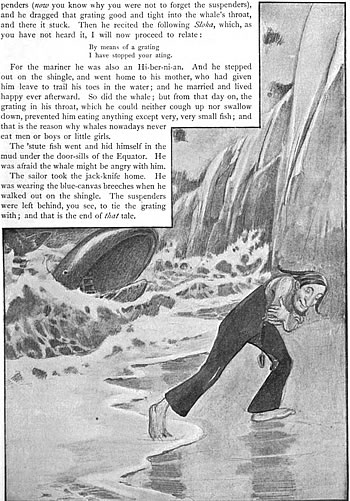

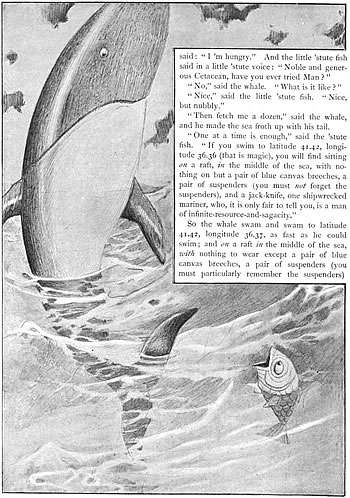

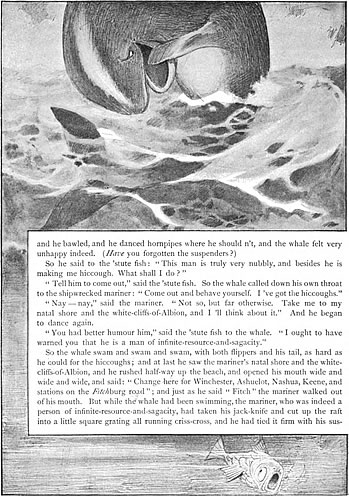

'How the Whale Got his Tiny Throat', 1897 version

Here are images of pages from the first appearance of 'How the Whale Got his Tiny Throat', the first of the then three 'Just So Stories', St. Nicholas Magazine, Volume XXV, No. 2, December 1897, pp. 89-93.

The illustrations are by Oliver Herford (1860-1935), an artist and writer who was famed for his wit and wacky imagination – well suited to illustrating Kipling's surreal prose. The 1902 book edition, however, used Kipling's own drawings following the encouragement of his artist father, Lockwood Kipling.

[Click on a page image to open a larger version in a new browser tab.]

None of these three 1897 stories contains the expression 'Best Beloved' or any variant of it.

This first appearance of the group of three 'Just So Stories' is prefixed with a prologue. This firmly identifies the stories as suitable for reading to children, particularly in the evenings with soporific effect. It introduces Effie (Kipling's firstborn daughter, then four years old) and explains that the group title of the three as 'Just So Stories' comes from her insistence that the stories always be read in exactly the same way – 'just so'.

Five years later, for the 1902 first edition of the book The Just So Stories the prologue was dropped. This oddity excites our interest and we shall deal with it anon.

Prologue to 'How the Whale Got his Tiny Throat' (1897)

From the St. Nicholas Magazine, Volume XXV, No. 2, December 1897. Not included in the first collected edition of 1902.

SOME stories are meant to be read quietly and some stories are meant to be told aloud. Some stories are only proper for rainy mornings, and some for long, hot afternoons when one is lying in the open, and some stories are bedtime stories. All the Blue Skalallatoot stories are morning tales (I do not know why, but that is what Effie says). All the stories about Orvin Sylvester Woodsey, the left-over New England fairy who did not think it well-seen to fly, and who used patent labour-saving devices instead of charms, are afternoon stories because they were generally told in the shade of the woods. You could alter and change these tales as much as you pleased; but in the evening there were stories meant to put Effie to sleep, and you were not allowed to alter those by one single little word. They had to be told just so; or Effie would wake up and put back the missing sentence. So at last they came to be like charms, all three of them, the whale tale, the camel tale, and the rhinoceros tale. Of course little people are not alike, but I think if you catch some Effie rather tired and rather sleepy at the end of the day, and if you begin in a low voice and tell the tales precisely as I have written them down, you will find that that Effie will presently curl up and go to sleep.

Now, this is the first tale, and it tells how the whale got his tiny throat :—

Josephine 'Effie' Kipling, dressed and posed for a formal photograph in the loggia of the Kiplings' house in Vermont, 'Naulakha' ca. 1895. The Kiplings lived there between August 1893 and September 1896.

Some photographs dating from the Kiplings' stay at the Rock House, Torquay (September 1896 to May 1897). Clockwise from top left: Effie and Carrie; Effie and Elsie, spring 1897; Effie opposite the greenhouse door, 1897; Effie in charge of Elsie, spring 1896;

'How the Whale Got his Throat', 1902 version

The 1902 version of the first tale, now titled 'How the Whale Got his Throat', is substantially different from the 1897 version of the tale. Let's look at a comparison (more drudgery, more counting – whoopee!)

All the changes have an interest for drudges like me, we plodders who like to watch genius at work, but I want to focus particularly on the remarkable epithet 'Best Beloved' that we looked at in my previous article.

The text given here is that of the first book edition of The Just So Stories in 1902. The text differences between that and the first appearance in print, in the St. Nicholas Magazine of 1897, are marked up as follows:

Text marked green differs from the 1897 version. Clicking on the marker will display the relevant text from the 1897 edition; a further click (on any element) will close the display. Text elements marked in blue are new in the 1902 edition.

Please note: The comparison only displays differences in significant text. There were numerous changes to punctuation, but for our present purposes these are unimportant and most of them have been ignored.

In the sea, once upon a time, O my Best Beloved, there was a Whale, and he ate fishes. He ate the starfish and the garfish, and the crab and the dab, and the plaice and the dace, and the skate and his mate, and the mackereel and the pickereel, and the really truly twirly-whirly eel. All the fishes he could find in all the sea he ate with his mouth so—! Till at last there was only one small fish left in all the sea, and he was a small 'Stute Fish, and he swam a little behind the Whale's right ear, so as to be out of harm's way. Then the Whale stood up on his tail and said, 'I'm hungry.' And the small 'Stute Fish said in a small 'stute voice, 'Noble and generous Cetacean, have you ever tasted Man?'

'No,' said the Whale. 'What is it like ?'

'Nice,' said the small 'Stute Fish. 'Nice but nubbly.'

'Then fetch me some,' said the Whale, and he made the sea froth up with his tail.

'One at a time is enough,' said the 'Stute Fish. 'If you swim to latitude Fifty North, longitude Forty West (that is magic), you will find, sitting on a raft, in the middle of the sea, with nothing on but a pair of blue canvas breeches, a pair of suspenders (you must not forget the suspenders, Best Beloved), and a jack-knife, one shipwrecked Mariner, who, it is only fair to tell you, is a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.'

So the Whale swam and swam to latitude Fifty North, longitude Forty West, as fast as he could swim, and on a raft, in the middle of the sea, with nothing to wear except a pair of blue canvas breeches, a pair of suspenders (you must particularly remember the suspenders, Best Beloved), and a jack-knife, he found one single, solitary shipwrecked Mariner, trailing his toes in the water. (He had his mummy's leave to paddle, or else he would never have done it, because he was a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.)

Then the Whale opened his mouth back and back and back till it nearly touched his tail, and he swallowed the shipwrecked Mariner, and the raft he was sitting on, and his blue canvas breeches, and the suspenders (which you must not forget), and the jack-knife—He swallowed them all down into his warm, dark, inside cupboards, and then he smacked his lips — so, and turned round three times on his tail.

But as soon as the Mariner, who was a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity, found himself truly inside the Whale's warm, dark, inside cupboards, he stumped and he jumped and he thumped and he bumped, and he pranced and he danced, and he banged and he clanged, and he hit and he bit, and he leaped and he creeped, and he prowled and he howled, and he hopped and he dropped, and he cried and he sighed, and he crawled and he bawled, and he stepped and he lepped, and he danced hornpipes where he shouldn't, and the Whale felt most unhappy indeed. (Have you forgotten the suspenders?)

So he said to the 'Stute Fish, 'This man is very nubbly, and besides he is making me hiccough. What shall I do?'

'Tell him to come out,' said the 'Stute Fish.

So the Whale called down his own throat to the shipwrecked Mariner, 'Come out and behave yourself. I've got the hiccoughs.'

'Nay, nay!' said the Mariner. 'Not so, but far otherwise. Take me to my natal-shore and the white-cliffs-of-Albion, and I'll think about it.' And he began to dance more than ever.

'You had better take him home' said the 'Stute Fish to the Whale. 'I ought to have warned you that he is a man of infinite-resource-and-sagacity.'

So the Whale swam and swam and swam, with both flippers and his tail, as hard as he could for the hiccoughs; and at last he saw the Mariner's natal-shore and the white-cliffs-of-Albion, and he rushed half-way up the beach, and opened his mouth wide and wide and wide, and said, 'Change here for Winchester, Ashuelot, Nashua, Keene, and stations on the Fitchburg Road;' and just as he said 'Fitch' the Mariner walked out of his mouth. But while the Whale had been swimming, the Mariner, who was indeed a person of infinite-resource-and-sagacity, had taken his jack-knife and cut up the raft into a little square grating all running criss-cross, and he had tied it firm with his suspenders (now you know why you were not to forget the suspenders!), and he dragged that grating good and tight into the Whale's throat, and there it stuck! Then he recited the following Sloka, which, as you have not heard it, I will now proceed to relate —

By means of a grating

I have stopped your ating.

For the Mariner he was also an Hi-ber-ni-an. And he stepped out on the shingle, and went home to his mother, who had given him leave to trail his toes in the water; and he married and lived happily ever afterward. So did the Whale. But from that day on, the grating in his throat, which he could neither cough up nor swallow down, prevented him eating anything except very, very small fish; and that is the reason why whales nowadays never eat men or boys or little girls.

The small 'Stute Fish went and hid himself in the mud under the Door-sills of the Equator. He was afraid that the Whale might be angry with him.

The Sailor took the jack-knife home. He was wearing the blue canvas breeches when he walked out on the shingle. The suspenders were left behind, you see, to tie the grating with; and that is the end of that tale.

For the 1902 book Kipling added a poem to each of the stories. To 'How the Whale Got his Throat' he added the poem 'Fifty North and Forty West':

Fifty North and Forty West

WHEN the cabin portholes are dark and green

Because of the seas outside;

When the ship goes wop (with a wiggle between)

And the steward falls into the soup-tureen,

And the trunks begin to slide;

When Nursey lies on the floor in a heap,

And Mummy tells you to let her sleep,

And you aren’t waked or washed or dressed,

Why, then you will know (if you haven’t guessed)

You’re 'Fifty North and Forty West!'

The camel and the rhinoceros

The other two stories 'How the Camel Got His Hump' and 'How the Rhinoceros Got His Skin' that appeared in the St. Nicholas Magazine were also lightly edited for the 1902 edition. I haven't got the energy to display a detailed comparison of the two versions of these two stories, you'll just have to accept my executive summary with a sigh of relief, which is that there are a few signs of editing, but the touch is very light. Certainly, no 'Best Beloved's were added.

To these two stories poems were appended, just like all the other stories. No trace of Effie, though, since the term 'Best Beloved' or anything like it is never used. The reason Kipling edited them but did not personalise them as he did in the whale story has to be one of the many things I currently don't know and probably never will know.

Above and right: Effie in Naulakha, the Kipling's house in Vermont.

_350x300.jpg)

Summary

Leaving aside for a moment all the new material he had produced for the 1802 book (nine further stories, illustrations with captions and poems), there are other very substantial changes between the first story in the editions of 1897 and 1902: Kipling supplied his own illustrations, including explanatory text to go with them; he also added a concluding poem.

So, to summarise for the moment, between 1897 and 1902, in 'How the Whale Got his Throat':

- The text was edited substantially and Kipling supplied his own illustrations.

- The epithet 'Best Beloved' was added.

- The poem 'Fifty North and Forty West' was appended and the text was adapted to fit.

- The other two poems in the 1897 original set of three were only lightly edited and the epithet 'Best Beloved' was not added.

So sometime between 1897 and 1902, the epithet 'Best Beloved' was worked into the story 'How the Whale Got his Tiny Throat' and would be used extensively after that. The poem 'Fifty North and Forty West' about a horrible ocean crossing was appended.

The nightmare in New York

Two years after settling in Britain, the Kiplings decided to visit the USA in the winter of 1898. When they were living in England their habit was to overwinter in South Africa. In 1898, though, various duties called them to the USA.

Josephine, John and Elsie in London 1898 Image: © National Trust / Charles Thomas

They sailed from Liverpool to New York on the SS Majestic. It turned out to be the roughest crossing they had ever known. The whole family was weakened by seasickness and the three children and their nurse, Lucy Blandford, fell ill. They docked in New York on 2 February 1899.

The White Star Line SS Majestic leaving New York harbour in 1903. The ship looks like something that will be an interesting experience in heavy seas: 'the cabin portholes are dark and green'. It came into service in 1890 on the Liverpool-New York route, a crossing which took almost seven days. From 1895 until 1904 its captain was Edward Smith, who would crown his career in 1912 by running the Titanic into an iceberg. On their winter crossing the Kiplings could consider themselves lucky. After the Titanic sank, the Majestic was brought out of retirement to replace it. Image: unknown source.

Fifty North and Forty West

The poem that would be appended to the 1902 version of 'How the Whale Got His Throat' recalls the horrors of that Atlantic crossing recounted in humorous verse. The experience is fully integrated into the story through the repetition in various forms of 'latitude Fifty North, longitude Forty West'.

The description of the awful crossing could only have been added to the story after the fact. Adding this poem to the whale story also required some changes in the text. The whimsical coordinates given to the whale in the initial text, 'latitude 41.42, longitude 36.37 [clearly not '36.36'] (which if East placed the ship inland on the southern shore of the Black Sea, if West almost exactly mid-North Atlantic), were changed to the more euphonious and meaningful form 'latitude 50 North and longitude 40 West', which corresponded with a position on or near the route the Kiplings had sailed on the SS Majestic.

Illness and the death of Effie

Josephine and little sister Elsie had bad colds and bronchitis and on arrival were put to bed in the Hotel Grenoble.

The Hotel Grenoble in New York on Seventh Avenue, West 56th Street in the late 1890s. Close to the Carnegie Hall and Central Park and specialised in accommodating European customers. Image: unknown source.

Carrie fell ill, though not for long. Rudyard, too, fell ill on 20 February and was confined to his room in the hotel. At first his situation did not seem serious – he was sitting in bed and working. Effie's condition on the other hand did not get better and she developed pneumonia.

For some reason, Carrie decided to have Effie transferred from the hotel (where medical specialists were attending Rudyard) to a friend's house. So on 22 February 1899, in a high fever, Effie was transported in the severe conditions of a New York winter twenty-one blocks away on Long Island.

Rudyard became seriously ill and was even thought to be close to death at one point. He gradually began to recover at the beginning of March and by 4 March the worst was over. But Effie, perhaps as a result of the winter trip to Long Island, never recovered. She died in the early morning of 6 March and was cremated shortly after.

At this moment Rudyard had relapsed into a delirium, but by 9 March his condition began to improve. The news of Effie's death was kept from him for around two weeks. When he was finally told, in his grief there were harsh words exchanged with his wife about the stupidity of moving Effie under those conditions, but Rudyard soon came to terms with it, since with everyone around her ill, Carrie was the last man standing with a lot to bear.

Caroline Starr Balestier, Mrs Rudyard Kipling (1862-1939) by Sir Philip Edward Burne-Jones (1861-1926), 1899. Unfortunately one of Burne-Jones' least convincing portraits – consider the book awkwardly propped in her waist and the quite painful looking wrist position holding it there. Then there is the lifeless stare… and always the question: why do so many portraits of women turn into portraits of a favourite dress? Image: ©National Trust Images / John Hammond

The Kiplings were, in their own different ways, totally distraught at the death of Effie. For many years after, those who knew Rudyard noted his underlying sadness – he was a changed man. Carrie was keeping things together for the family and supressed her grief behind a wall of silence. It came out, however, in a conversation with Alice Kipling, her mother-in-law, sometime after they had returned to England. Up until then the two women had disliked each other. At some point the dam broke and Effie's death brought them together in floods of tears.

Ghosts and memories

In 1899 they returned from the USA to their home in England, The Elms in Rottingdean, near Brighton, East Sussex, where they had been living since 1897. Here there was no chance to forget their lost child – memories of Effie were everywhere: the nursery, the garden and all the places round about which she had visited with her Daddy.

A postcard photo of the The Elms the Kiplings house in Rottingdean (date unknown) Image: Source unknown.

The house and garden are full of the lost child and poor Rud told his mother how he saw her when a door opened, when a space was vacant at table – coming out of every green dark corner of the garden – radiant and – heartbreaking.

Remark by Lockwood Kipling, Rudyard's father, reproduced in Lycett, p. 315. There are a number of poems in Friedrich Rückert's Kindertodtenlieder in which grief and loss call up near-hallucinations of the dead child's presence still among the familiar everyday, see here and here.

Another pending problem was their house 'Naulakha' in Vermont. After the nightmare in New York in 1899, compounded by his brother-in-law's threat to sue him, it was obvious that he would never return to the USA. Two years later, in 1901, he put 'Naulakha' up for sale. It had been a project of the heart for them both while they were there, but it was now one more thing indelibly associated with Effie.

Josephine Kipling in the loggia of the Kiplings' house 'Naulakha' ca. 1895.

Nevertheless, Rudyard continued with his Just So Stories. In 1902, the year of the publication of the first edition of the Just So Stories with its twelve stories now in book form, the Kiplings bought and settled in Bateman's, a large property built in 1634 and located in rural Burwash, Sussex. Rudyard and Carrie would live there for the rest of their lives.

Bateman's, the home of Rudyard Kipling and his family in East Sussex from 1902 onwards. Images: ©National Trust Images/Jo Hatcher/James Dobson

The parallel is not unjust: the publication of the Just So Stories strikes us as being a moment of closure for the loss of Effie; the new house freed them from the daily confrontations with the now empty spaces of the stories' presiding spirit.

In 1904 Kipling published his short story They. Although two years later than the Just So Stories it represents another effort of Kipling's to come to terms with the loss of Effie. It is the story of a blind lady in a house haunted by the ghosts of dead children, who can only be seen or heard by parents who have lost children. The narrator discovers that his own deceased daughter is among them when the palm of his hand is kissed:

The little brushing kiss fell in the centre of my palm — as a gift on which the fingers were, once, expected to close: as the all faithful half-reproachful signal of a waiting child not used to neglect even when grown-ups were busiest — a fragment of the mute code devised very long ago.

They, p. 8.

The narrator realises that he, unlike the blind lady, could not live like this – unlike her, 'For me it would be wrong. For me only…'. He leaves the house, the blind lady and the children and goes back to the living, never to return, separated for ever from his daughter.

The 'Best Beloved' and the 'little girl-daughter'

Rudyard and bright-spark Effie in their house Naulakha in Vermont.

Was all the revision work on the three 1897 stories carried out after Effie's death? It seems reasonable to assume that the whale story was edited after her death, because of the inclusion of the poem describing their terrible passage to New York. I do not know when the other two tales were revised.

We perhaps can begin to understand the terrible significance of the 'Best Beloved' epithet itself. These stories would never now be told to Effie at bedtime. The epithet could be left for her siblings Elsie (1896-1976) and John (1897-1915). At the time of Effie's death Elsie was three and John was eighteen months old.

It is possible that Kipling thought up the epithet before Effie's death, but it seems more likely that it was part of a process of memorialising her in the Just So Stories – he is now reading to her beyond the grave. He leaves behind other tokens of her presence, for example the epithet 'little girl-daughter' or 'Little Girl Daughter' or 'Girl Daughter'. As a consequence of her death she will now always be the 'little girl-daughter'. The term is introduced in 'How the First Letter Was Written', but was extensively used in 'The Crab That Played with the Sea':

But towards evening, when people and things grow restless and tired, there came up the Man (With his own little girl-daughter?) – Yes, with his own best beloved little girl-daughter sitting upon his shoulder, and he said, ' What is this play, Eldest Magician?'

'When people and things grow restless and tired' is also an allusion to Effie, the little girl-daughter. The thirteenth story we have left out of consideration, 'The Tabu Tale' is a parable for Effie, her restless activity and her inability to respect the word 'no'.

As already noted, the poem 'Fifty North and Forty West' must have been composed after that terrrible crossing and almost certainly after Rudyard had recovered – perhaps still in New York, perhaps on the ship back, perhaps in England. As he produced new stories for the collection, he addressed them all to the little girl, his 'Best Beloved', who now would now never hear them.

A charming photograph of Josephine 'Effie' Kipling, mounted in an elaborate gold frame, indicative of the depth of her parents' loss. Image: ©National Trust / Charles Thomas

The blow to Rudyard from Effie's death was immense. Her death must be counted the greatest tragedy of his life, perhaps more so than the death of his eighteen year-old son John whilst taking part in an infantry attack in Loos on 27 September 1915, one of the 10'000 men who lost their lives that day.

He somehow dealt with the loss of his beautiful and clever daughter and kept scribbling. He kept on with the Just So Stories, kept on with the tone, the playfulness and the sparkling wit – and each time with 'Best Beloved'. Four more stories came 'How the Leopard Got His Spots', 'The Elephant’s Child', 'The Singsong of Old Man Kangaroo' and 'The Beginning of the Armadillos'. All four of them followed the form established in the previous works.

Effie and Taffy – her Daddy's farewell

But the next two stories, 'How the First Letter Was Written' and 'How the Alphabet Was Made', are radically different from everything that had gone before. They stand out as Rudyard's literary farewell to Effie in the collection of stories to which she had given the title and which had now become her memorial.

In a remarkable leap of imagination, Kipling made Effie the main character of these two stories in the character of 'Taffy' and simultaneously still spoke directly to her as 'Best Beloved'. The stories stand out as something special in the collection in that they were no longer origin myths about various animals, but origin myths of pictographic and alphabetic writing set in a Neolithic nuclear human family:

His name was Tegumai Bopsulai, and that means, 'Man-who-does-not-put-his-foot-forward-in-a-hurry'; but we, O Best Beloved, will call him Tegumai, for short. And his wife’s name was Teshumai Tewindrow, and that means, 'Lady-who-asks-a-very-many-questions'; but we, O Best Beloved, will call her Teshumai, for short. And his little girl-daughter’s name was Taffimai Metallumai, and that means, 'Small-person-without-any-manners-who-ought-to-be-spanked'; but I’m going to call her Taffy. And she was Tegumai Bopsulai’s Best Beloved and her own Mummy’s Best Beloved, and she was not spanked half as much as was good for her; and they were all three very happy. As soon as Taffy could run about she went everywhere with her Daddy Tegumai, and sometimes they would not come home to the Cave till they were hungry, and then Teshumai Tewindrow would say, 'Where in the world have you two been to, to get so shocking dirty? Really, my Tegumai, you’re no better than my Taffy.'

We meet the Neolithic family of Rudyard (Tegumai), his wife Carrie (Teshumai) and the little 'girl-daughter' Effie (Taffy), who was the 'Best Beloved' of both her parents. Taffy and her father are kindred spirits running free in the wide world, while wife Teshumai is the unwobbling pivot in the home to which they always return after every adventure.

The description of the idyllic Neolithic life sets Taffy centre-stage, for she is the one who invents pictograms – and thus writes the first letter. She's very modest about her invention, but the whole tribe is happy.

Tegumai, Teshumai and Taffy also feature in the next story, 'How the Alphabet Was Made'. Not only is this another story about humans, not animals, the two stories are also unique in the collection in that they form a pair.

'Taffy' was the nickname of a close journalist friend that Rudyard had met in South Africa, Howell Arthur Keir Gwynne (1865-1950). Gwynne was Welsh, born in Swansea, and known simply as Taffy to his friends. There is no obvious reason for associating the Welsh Taffy with the Neolithic Taffy, apart from the fact that he got on well with the Kipling children, so we file this information under 'Pointless Trivia'.

In the second story, Tegumai and Taffy work together to invent the alphabet. Teshumai (Carrie) makes an appearance as the homemaker, but almost all the action consists of Tegumai (Kipling) and Taffy (Effie) working cooperatively on their invention. There is a cameraderie between the two wild things when Teshumai ticks them both off for coming home late and dirty.

The 'magic alphabet-necklace'. Left, Kipling's illustration at the end of the story 'How the Alphabet Was Made' and right, a reconstruction created as a gift by a jeweller, now framed in a special presentation case at Bateman's. Image: ©National Trust Images/James Dobson

Kipling described the 'alphabet necklace' shown above at great length and in great detail. It was made by Taffy's father Tegumai. Perhaps its importance is that it is a cultural creation that outlasts human mortality:

ONE of the first things that Tegumai Bopsulai did after Taffy and he had made the Alphabet was to make a magic Alphabet-necklace of all the letters, so that it could be put in the Temple of Tegumai and kept for ever and ever. All the Tribe of Tegumai brought their most precious beads and beautiful things, and Taffy and Tegumai spent five whole years getting the necklace in order.

p. 165.

The invention of the alphabet (and all the other writing systems that preceded it) is a crucial moment in the development of humans, for it takes them from the prehistoric (which has only left us material artefacts) to the historic (written history).

The verse that closes the first story of the pair, 'How the First Letter Was Written' can be counted as a stroke of genius, although we may not realise it at first reading, before we have read the companion verse in the next story.

The poem takes us two steps back through time from the present, through Ancient Britain and then to Taffy and her family in the landscape of the prehistoric Neolithic Age. Taking two steps to do this heightens the distance between our age and the Neolithic. She and her family and her tribe are no more:

There runs a road by Merrow Down—

A grassy track today it is—

An hour out of Guildford town,

Above the river Wey it is.Here, when they heard the horse-bells ring,

The ancient Britons dressed and rode

To watch the dark Phoenicians bring

Their goods along the Western Road.And here, or hereabouts, they met

To hold their racial talks and such—

To barter beads for Whitby jet,

And tin for gay shell torques and such.But long and long before that time

(When bison used to roam on it)

Did Taffy and her Daddy climb

That down, and had their home on it.Then beavers built in Broadstonebrook

And made a swamp where Bramley stands:

And bears from Shere would come and look

For Taffimai where Shamley stands.The Wey, that Taffy called Wagai,

Was more than six times bigger then;

And all the Tribe of Tegumai

They cut a noble figure then!

The verse that closes the second of the stories, 'How the Alphabet was Made' forms a pair with the verse of the previous story, 'How the First Letter was Written'.

The second poem is also a work of genius, an absolutely heart-rending vision of Kipling's loss of Effie, represented by her fictional persona, Taffy. If you have tears, prepare to shed them now:

But I remember Tegumai Bopsulai, and Taffimai Metallumai and Teshumai Tewindrow, her dear Mummy, and all the days gone by.

And it was so—just so—a little time ago—on the banks of the big Wagai!Of all the Tribe of Tegumai

Who cut that figure, none remain—

On Merrow Down the cuckoos cry—

The silence and the sun remain.But as the faithful years return

And hearts unwounded sing again,

Comes Taffy dancing through the fern

To lead the Surrey spring again.Her brows are bound with bracken-fronds,

And golden elf-locks fly above;

Her eyes are bright as diamonds

And bluer than the skies above.In mocassins and deerskin cloak,

Unfearing, free and fair she flits,

And lights her little damp-wood smoke

To show her Daddy where she flits.For far—oh, very far behind,

So far she cannot call to him,

Comes Tegumai alone to find

The daughter that was all to him.

What Kipling has done here is extraordinarily clever. He believed there was a God, but without the theological trappings of the afterlife. Removing the 1897 prologue means that Effie is not mentioned by name in the Just So Stories, she is now 'Best Beloved' (which may also now refer to the Kiplings' other children – did he read Effie's bedtime stories to them, too? Son John was really not the target audience for these girly tales. One more thing I do not know).

Grief may be the reason for the removal of the prologue that introduced the three stories printed in 1897. After her death she is only referred to by the epithets 'Best Beloved', 'little girl-daughter' or by her Neolithic proxy, 'Taffy'. That, I think, is one of the reasons why the prologue was eliminated. The Just So Stories were her stories, but she had to be removed in a way that didn't lose her. If you just read the Just So Stories as they are today and read no commentary then you would know nothing about Effie.

Rudyard took her out of the work, or rather, distanced it from her, with allusions and memories that only he would understand. For example, the river Wey/Wagai seems to have been a favourite outing for the pair, somewhere Effie could go paddling, dipping her toes 'with her Daddy's leave'. She was the little girl-daughter of him and of Carrie, not anyone else.

Effie has left her mark, though, whether named or not, for the children of the Just So Stories are all girls. They were stories for her, and will always be so.

In the 'Letter' and 'Alphabet' pair of stories Effie takes on the persona of Taffy, a Neolithic girl, and Rudyard and Carrie also are given their Neolithic personae too. She is not spooking around in some spiritualist afterlife – it was high season for spiritualists and séances during Kipling's lifetime. Spook business was particularly good in the years after the First World War, with so many bereaved parents and relations trying to contact their dead soldier sons.

She (Taffy/Effie) can never reach back to contact her father (Tegumai/Rudyard) across the wastes of time and he can never catch her up. She may light her 'little damp-wood smoke', but her Daddy can never see it. The situation is complex and subtle, bordering on the incomprehensible, but quite brilliant.

For those who have eyes to read or ears to hear, the wacky bedtime stories written to be read 'just so' by adults to 'little children', their own Best Beloveds, are infused with Rudyard's inconsolable grief for the loss of his Best Beloved, Effie, in turn metaphorically represented via Tegumai's irremediable loss of his Best Beloved, Taffy. The stories are a farewell.

Spirits and ghosts are impermissible. Even if they exist they are static, there is no future in them, no development, no learning, no sharing. You cannot take them exploring in the woods, walking the Downs or paddling in the river.

As we saw in Kipling's short story They, the narrator encounters the shade of his dead daughter and realises that her shade is not her – if it exists it is a natural phenomenon, much like a reflection. Spiritualism's spooks are no replacement for his loss.

Taffy can never reach Tegumai, although their invention of the magic alphabet allows communications that last beyond the immediate moment and beyond life itself. 'Magic' indeed! In this sense, Rudyard's magic with the alphabet and the words it makes and the thoughts they carry has created in the Just So Stories the artefact that survives Effie and Carrie and Rudyard himself – 'so long lives this and this gives life to thee'.

For the duration of the Just So Stories Kipling expresses his grief through symbols and metaphors, but ultimately his Best Beloved, Effie/Taffy is beyond his reach. He last saw her when they entered the Hotel Grenoble in New York; when his illness relented he emerged only to find an urn with her ashes. He had held no vigil during her dying, had said no farewell. Now she no longer exists beyond his memories of her and in the artefacts she left behind, just as the Neolithics Tegumai and Taffy, now unreachable, left their artefacts behind as the world, its landscapes and its people changed without them. The Just So Stories are her memorial and for Rudyard the completion of some pressing unfinished business.

Update 12.08.2025

The dates of first publication have been added to the table. Dates of composition are not given – they are often uncertain or just guesswork.

Some small changes were made to the text during this process.

Update 31.08.2025

Though I, dim bulb, was struck by the highly specific allusion in the second poem to Taffy's 'little damp-wood smoke', I never went any further with it.

The phrase describes Taffy making smoke signals, which are such a feature of our understanding of Native American life. Two lines before, we read that she is dressed in 'mocassins and deerskin cloak', the former being another characteristic of American Indian culture (our word mocassin is of native American origin). Furthermore, clothing during most of the Neolithic period was mainly made of animal skins, so that Taffy's 'deerskin cloak' and 'mocassins' were quite characteristic for the period generally (although in the USA other terms are used instead of Neolithic).

Josephine/Effie was born and spent the first four years of her life in Vermont. We have no evidence, but it would come as no surprise to find that Rudyard and his Effie would spend time (presumably) in the woods around their house Naulakha (or perhaps in Rottingdean, when she was a little older) playing at 'Red Indians', scratching messages and following trails. They must have been happy moments, to find them now memorialised in Effie's alter ego, Taffy.

A father/daughter hunting session (set in Neolithic Sussex) is described in the story 'The Tabu Tale', which was not included in the canonical Just So Stories:

When Taffimai Metallumai (but you can still call her Taffy) went out into the woods hunting with Tegumai, she never kept still. She kept very unstill. She danced among dead leaves, she did. She snapped dry branches off, she did. She slid down banks and pits, she did quarries and pits of sand, she did. She splashed through swamps and bogs, she did; and she made a horrible noise! So all the animals that they hunted — squirrels, beavers, otters, badgers, and deer, and the rabbits — knew when Taffy and her Daddy were coming, and ran away.

From 'The Tabu Tale'.

One just needs to look at the few photos we have of her – sparky, bright as a button, radiating charisma into the camera lens – to realise that Rudyard would often wish for a 'Still Tabu' to shut his Best Beloved up now and again.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!