Second Lieutenant John Kipling

Richard Law, UTC 2025-09-27 07:14

On this day 110 years ago the eighteen year-old John Kipling (1897-1915), Rudyard and Carrie Kipling's only son, was killed on the battlefield of Loos, France on 27 September 1915. His was one name among the 10'000 men who lost their lives that day, one more name among the nearly 60'000 British casualties of the battle of Loos, which ran from 5 September to 8 October.

The Germans suffered around 26'000 casualties and ultimately retained the territory they had been defending. In the obscene calculus of war the Germans were the clear victors and the British had nothing to show in return for their dead and wounded. So it goes, Billy, so it goes. (©Kurt Vonnegut)

Despite the strenuous efforts of his father to locate him, we have only fragmentary eyewitness accounts of his death. For many years he was listed as 'wounded and missing'. The grave containing what was left of a body that had been exhumed from the battlefield four years later in 1919 was only identified as his in 1992.

For King and Country against the Boche

The reasons why he was even fighting in the First World War are as opaque as the manner of his death. He failed his medical examination for the Navy and then his medical examination for the Army, both on account of his shortsightedness.

That he was eventually accepted despite his medical rejection was due to his father pulling strings at the highest levels. He was eventually enrolled into the Irish Guards, given a few weeks of training and dispatched as a 2nd Lieutenant to the war in France.

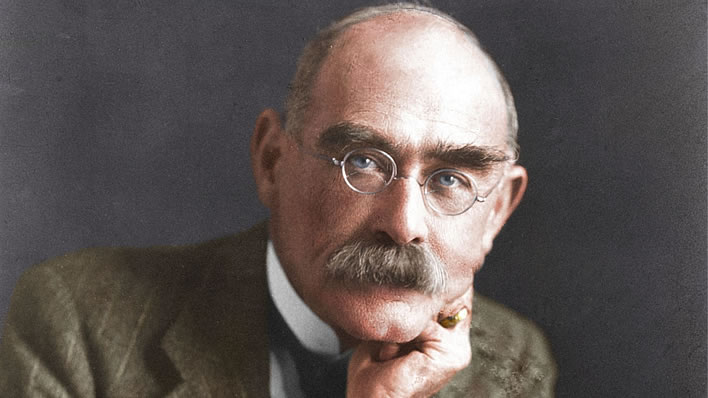

A portrait photograph of Rudyard Kipling (1924) by Elliott & Fry. Colourized detail.

Image: © National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG x81807.

Rudyard Kipling was unashamedly patriotic. The adverb 'unashamedly' is shorthand here for 'fought unapologetically against the anti-colonialist, anti-imperialist and globalist Zeitgeist that came to dominate the 20th century'. The Zeitgeist won, as it always does. The result is that today's intellectual Left, even if they may just about bring themselves to acknowledge Kipling's literary genius, despise the rest of him.

A wicked caricature of Kipling with Britannia by Max Beerbohm (1872-1956), who disliked him intensely. The drawing is subtitled 'Mr Rudyard Kipling takes a bloomin day aht, on the blasted 'eath, along with Britannia, 'is gurl'. It appeared in Beerbohm's book The Poets' Corner, (London, 1904)

So it is that the usual interpretation of John Kipling's enlistment is that Kipling senior, who by that time had developed a fiery hatred of the Germans and who was campaigning noisily for war, needed to avoid the scandal of his own son having avoided military service when so many others did their duty for which many of them paid a heavy price. The large band of Kipling-haters from that time until now are happy to believe that Kipling's militarism was responsible for sending his son to his early death in France and that his death was somehow appropriate karma for such a warmonger.

This assumption sounds plausible, but it neglects John Kipling's own enthusiasm for the cause. Apparently fit young men with two legs, two arms and two eyes, who were still in Britain, were frequently abused and shamed for not serving their country in France. The shaming would have been much worse for the son of such a public warmonger.

And I have seen no evidence that John Kipling, like many other young men of his time, went unwillingly into the army. We today, blessed with 20-20 hindsight, are appalled when we think of this generation of young men marching brightly and innocently into the meatgrinder – the unequal contest between high-explosive shells, machine-guns, rifle bullets, gas and human bodies – but for them it started out as an adventure.

John Kipling attended Wellington College, a private school principally for the sons of service members. He spent his early teenage years immersed in military lore and attitudes – military service would have been the logical extension of that schooling. The CiC of the Irish Guards would have had no hesitation in accepting a young man such as John Kipling, with or without his specs.

For many young men the adventure the war offered was an attraction. At first even the underlings and labourers who went into the ranks were happy to be freed for a time from the drudgery of their lives in mine and factory so they could go and 'biff the Kaiser on the nose'. They were the ones who dug the trenches and the tunnels for the mines and put up the barbed wire entanglements.

Given his background, John Kipling was almost certainly a willing participant, albeit at a more sophisticated level, so much so that he may have been the one pressing his father to get him into the army somehow, to do the patriotic duty in which he himself believed, safe from the judgement of the white feather mob.

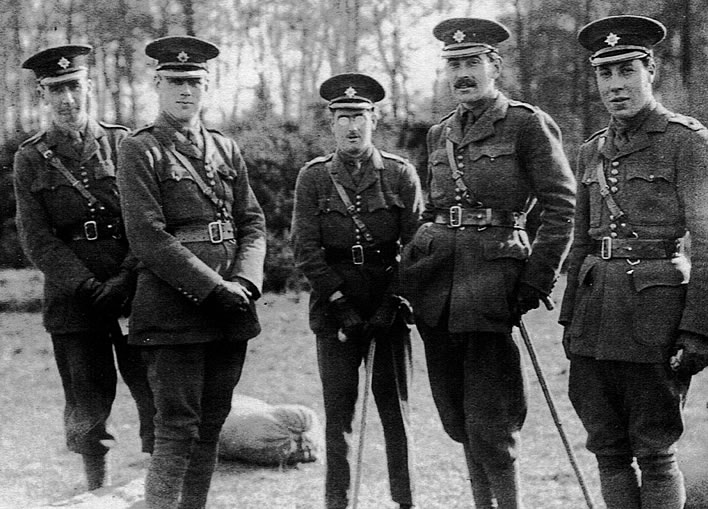

John Kipling (centre) and some other freshly-baked 2nd Lieutenants in happier, confident times. He inherited not only the shortsightedness of his father but also his compact stature. Image: National Trust

From the little we know of his time in the army he was not unwillingly there: he was not a slacker or a shirker or a grumbler. We can say this because at the time of his death his promotion to full lieutenant was in the pipeline and would be officially gazetted shortly after his death, so that his commanders had recognised his worth. Consider this: as far as we can make out, he died advancing without even the support of his company across the killing fields at the German strongpoints around Hill 70 and Chalk Pit Wood. Slackers and shirkers don't do things like that.

The worst we can say of Kipling senior is that he was an enabler. But given the public calumny to which his apparently fit son would be exposed had he not joined up, enabling is only to be expected. And if his son enthusiastically wanted to follow his friends into active service, what else could he do?

Deficits of understanding

The real problem here is that the modern person, unless he or she has read widely enough to get a deep insight into the culture of the early twentieth century, can scarcely imagine how different the attitudes and thinking of that time were to our own modern minds. The reader should consider yet again L.P. Hartley's wise statement from his novel The Go-Between: 'The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there' – and nowadays we always keep forgetting how differently things were done.

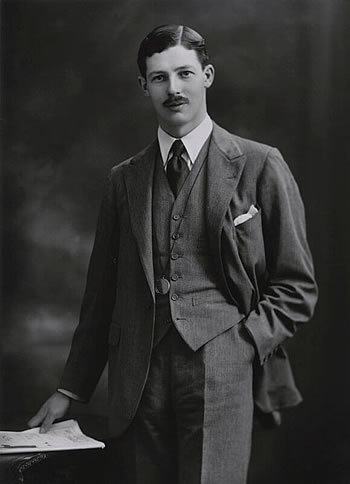

The former British Prime Minister, later 1st Earl of Stockton, Harold Macmillan (1894-1986, three years older than John Kipling), served in a Guards regiment at Loos, then after that on the Somme, where he was very gravely wounded but survived somehow. In the first volume of his autobiography, Winds of Change, 1914–1939 (1966) he described his military service.

Macmillan's calm insouciance at impending war puts John Kipling's desire to serve in a much more understandable light. But had Macmillan or Kipling known what horrors their war service would bring them, calm insouciance would have been difficult to maintain.

Harold Macmillan in 1920. Image: National Portrait Gallery, NPG x194364

In these weeks of waiting, I was naturally at a loss as to what to do; to continue the reading of Herodotus or Plato seemed inappropriate and likely in the long run to be a waste of time [Macmillan was at Balliol, Oxford, reading Mods (Latin and Greek)]. Soon, however, I was allowed to join the Artists’ Rifles, and began to drill in the Inns of Court, without uniform or rifles. At last, I was able to ‘pass out’, and found myself – how or why I do not recall – a second lieutenant in a new army battalion of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps.

One further obstacle had to be overcome – the medical examination. My body, I believed, was now sound [Macmillan had had some serious health issues], but I knew that my eyesight would be a serious hurdle. Fortunately, the pressure of men going through was very great, and made the medical officers correspondingly lenient. Actually, I suffered no serious difficulty from my need to wear (and carry spare) spectacles. The gas-mask was a bit of a problem. But I do not believe anybody could see much out of gas-masks, with or without spectacles.

In the late autumn of 1914 I found myself directed to join my battalion, the 19th I think it was, of this famous regiment, stationed at Southend-on-Sea. This, at any rate, was better than nothing; but there was still the fear that the war would be all over long before I could play any effective part. Over by Christmas – even after the early defeats and the stagnation that had settled on the Front – was still the common delusion. Kitchener, however, was known to have said it would last three years and, as members of Kitchener's Army, we put our hopes in him. But, without rifles, with little equipment, and with a state of readiness which even I could understand made our battalion quite unfit for operations, would the war last long enough for us?

Harold Macmillan, Winds of Change, 1914–1939, p. 61.

Macmillan, through his mother and his Oxford friends, pulled strings, just as Kipling did:

Naturally I turned to my mother, and by her help and the recommendation of one or two of my Oxford friends I was sent for and interviewed by the Lieutenant-Colonel of the Grenadier Guards, Sir Henry Streatfeild [Colonel Sir Henry Streatfeild, GCVO, CB, CMG, JP, DL (1857–1938), the royal equerry]. I could not help feeling the contrast when I went to see him at the Regimental Headquarters in Buckingham Gate. The smart saluting of the sentry and of the sergeant put me to shame. I was conscious that when I went in to see the Lieutenant-Colonel my bearing would be ignominiously unsoldierly. However, he asked only a few questions and put me at my ease. After a few weeks, I heard that my application had been successful. I was gazetted to the Reserve Battalion of the Grenadier Guards in March 1915.

Of course, readers today will exclaim that this was all wrong. It was all done by influence. It was privilege of the worst kind – and so it was. It was truly shocking. But, after all, was it so very reprehensible? The only privilege I, and many others like me, sought was that of getting ourselves killed or wounded as soon as possible.

Ibid. p. 64.

The Loos experience

Since the precise manner of John Kipling's death is somewhat obscure, it seems fitting to add some context about what we might call 'the Loos experience'. The writer Robert Graves (1895-1985) saw action in that battle on another part of the battlefield. He left us a vivid account of the battle of Loos in his autobiography Goodbye to All That (1929/1957).

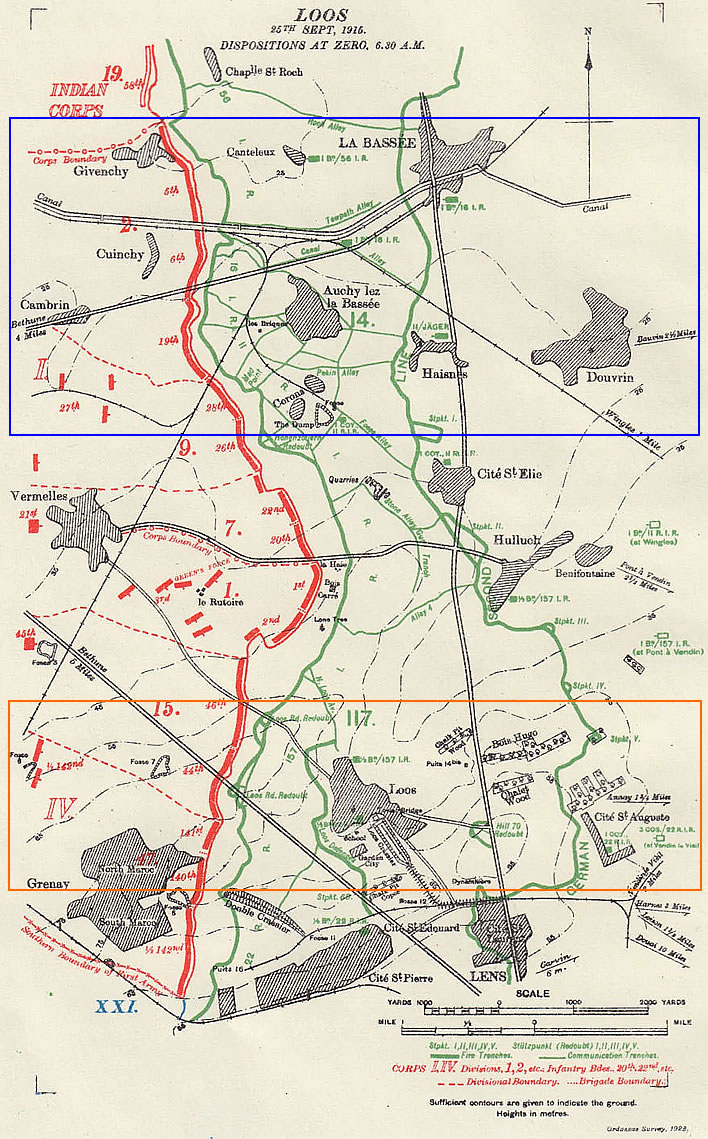

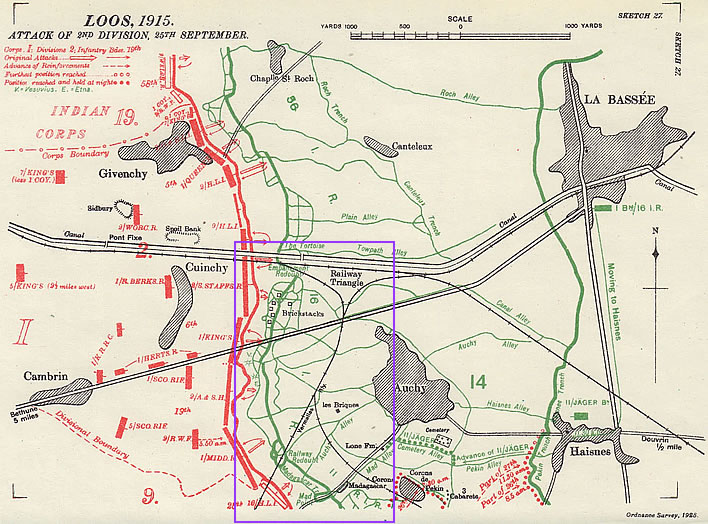

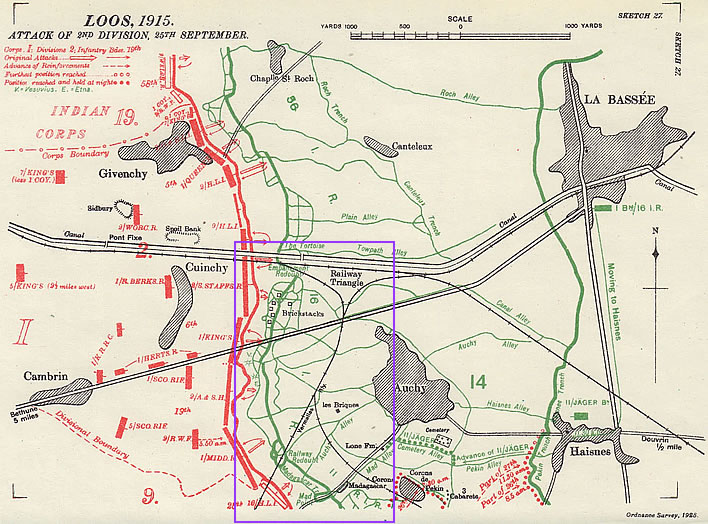

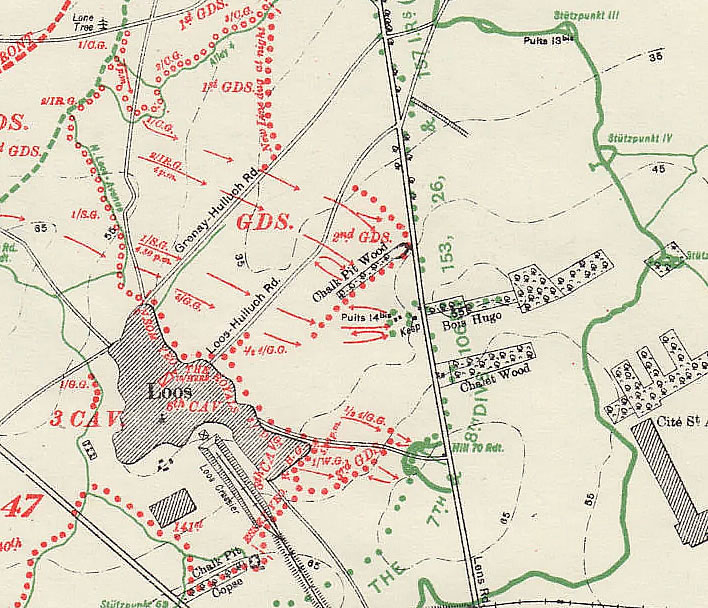

Here is a trench map of the battlefield at the start of the battle:

An overview of the trenches and troop dispositions of the entire Loos battlefield at the beginning of the engagement on 25 September 1915. British trenches and positions are shown in red, German in green.

Lt. Robert Graves' regiment, the 2nd Royal Welch Fusiliers ('2/R.W.F.') were attacking in the northern zone, marked by the blue rectangle; 2nd Lt. John Kipling's regiment, the 2nd Irish Guards, were part of the merged Guards division (in which Harold Macmillan was also serving), which attacked in the southern zone around Loos, indicated here by the orange rectangle [the Guards division arrived after the start of the battle and are not yet marked on this map].

All the trench maps in this article are taken from those produced by Major Archibald Frank Becke for the History of the Great War based on Official Documents by the Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence; 'Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915', compiled by Brigadier-General Sir James Edmonds, Vol. II, published by published by Macmillan and Co., London, 1928. [Click on a trench map image to display a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Robert Graves: the battle in the northern sector of Loos

The following excerpts are taken from the revised, 1957 edition of the book (Doubleday, New York). Occasional comments of mine and my subtitles are in [square brackets].

The text of the 1957 edition was very substantially changed from that of its 1929 predecessor. The amusing reason for this unusually thorough revision is that in 1943 Graves had published The Reader over your Shoulder, which announced itself as 'A Handbook for Writers of English Prose' and which gave aspiring writers all kinds of precepts and rules for writing prose. (My copy from 1963 cost '21s. net'.) While revising the first edition of Goodbye to All That, rather than just lightly tinkering with the work, hoist with his own petard, he was forced to undertake some substantial revisions to make it conform to his own literary precepts: 'Omission of many dull or foolish patches … and a general editing of my excusably ragged prose'. The existence of the two very different versions has of course caused publishing chaos. The text of the 1957 Penguin edition, for example, claims to use the revised text, but when compared with the Doubleday edition of 1957 displays some major differences. The text used here is that of the Doubleday edition.

A photograph of Robert Graves from around the time of his military service.

On September 19th we relieved the Middlesex Regiment at Cambrin, and were told that these would be the trenches from which we attacked. The preliminary bombardment had already started, a week in advance. As I led my platoon into the line, I recognized with some disgust the same machine-gun shelter where I had seen the suicide on my first night in trenches. It seemed ominous. This was by far the heaviest bombardment from our own guns we had yet seen. The trenches shook properly, and a great cloud of drifting shell-smoke obscured the German line. Shells went over our heads in a steady stream; we had to shout to make our neighbours hear. Dying down a little at night, the racket began again every morning at dawn, a little louder each time. ‘Damn it,’ we said, ‘there can’t be a living soul left in those trenches.’ But still it went on.

Dead German at the entrance to a deep dugout in a captured trench near Loos, 30th September, 1915. Image: IWM Q 28982

British dead in front of a captured German trench near Loos, 30th September, 1915. Image: IWM Q 28980

Barbed wire defences in front of captured German trench and machine gun emplacement, near Loos, 28th September 1915. Image: IWM Q 28976

The Germans retaliated, though not very vigorously. Most of their heavy artillery had been withdrawn from this sector, we were told, and sent across to the Russian front. More casualties came from our own shorts and blow-backs than from German shells. Much of the ammunition that our batteries were using was made in the United States and contained a high percentage of duds; the driving bands were always coming off. We had fifty casualties in the ranks and three officer casualties, including Buzz Off – badly wounded in the head [Buzz Off: A 'lieutenant-colonel with a red face and angry eye', the Second-in-command of the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Welch Fusiliers]. This happened before steel helmets were issued; we would not have lost nearly so many with those. I got two insignificant wounds on the hand, which I took as an omen of the right sort.

A typical and well-established trench, occupied by the Cheshire Regiment (one still alive, others dead) on the Somme battlefield in 1916. The soldier is kneeling on the firing step.

British troops holding a front line trench near the Hairpin Quarries, Loos, 19th January, 1916. Image: IWM Q 29052

[The attack briefing]

On the morning of the 23rd, Thomas [Graves' company commander, Captain G. O. Thomas: 'He was a regular of seventeen years’ service, a well-known polo-player, and a fine soldier. This is the descriptive order that he would himself have preferred.'] came back from Battalion Headquarters carrying a note-book and six maps, one for each of us company officers. ‘Listen,’ he said, ‘and copy out all this skite ['1869– A jollification, a spree, a binge.' OED] on the back of your maps. You'll have to explain it to your platoons this afternoon. Tomorrow morning we go back to dump our blankets, packs and greatcoats in Béthune. The next day, that’s Saturday the 25th, we attack.’ This being the first definitive news we had been given, we looked up half startled, half relieved. I still have the map, and these are the orders as I copied them down:—

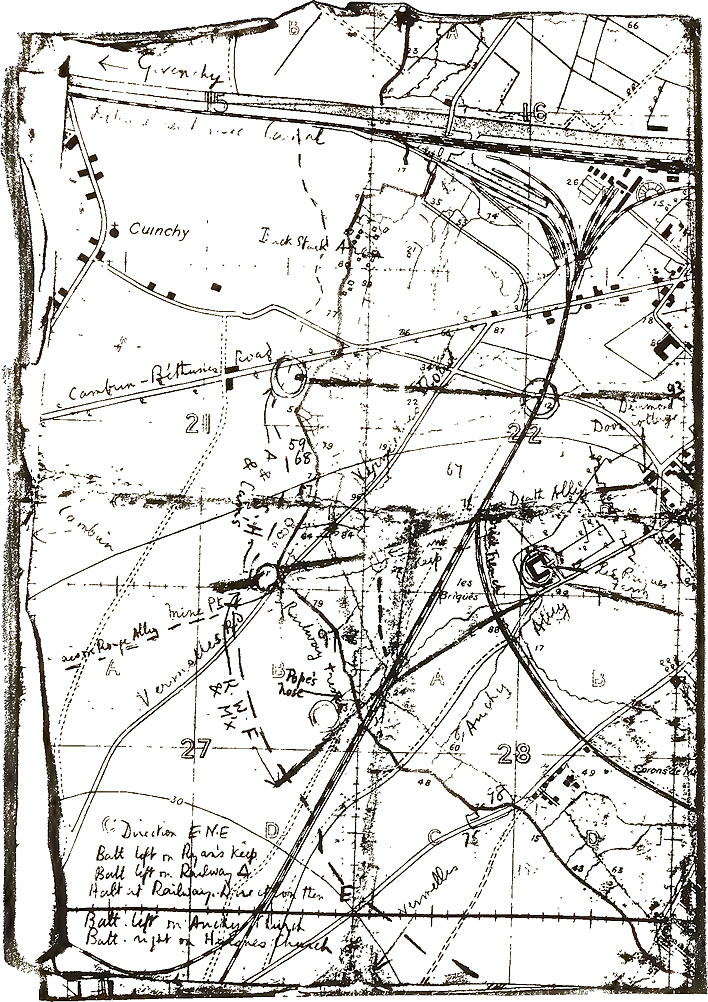

Robert Graves' trench map and battle instructions, annotated by him before the battle. [Click to open a large image in a new browser tab.]

The Royal Welch Fusiliers [R.W.F.] are in the reserve trench behind the Middlesex regiment in the front trench at the bottom of the map. The 10th Highland Light Infantry occupy the front trench to their right. Les Briques farm is a little to the left of Auchy; the 'Pope's Nose' was the troops' name for the 'Railway Redoubt' to the left of the rail line to Vermelles and just opposite the Middlesex front line. The purple rectangle marks the approximate limits of Graves' annotated battle map.

'First Objective — Les Briques Farm — The big house plainly visible to our front, surrounded by trees. To reach this it is necessary to cross three lines of enemy trenches. The first is three hundred yards distant, the second four hundred, and the third about six hundred. We then cross two railways. Behind the second railway line is a German trench called the Brick Trench. Then comes the Farm, a strong place with moat and cellars and a kitchen garden strongly staked and wired.

'Second Objective — The Town of Auchy — This is also plainly visible from our trenches. It is four hundred yards beyond the Farm and defended by a first line of trench half-way across, and a second line immediately in front of the town. When we have occupied the first line our direction is half-right, with the left of the Battalion directed on Tall Chimney.

'Third Objective — Village of Haisnes — Conspicuous by high-spired church. Our eventual line will be taken up on the railway behind this village, where we will dig in and await reinforcements.'

[…]

‘Between the six of us, but you youngsters must be careful not to let the men know, this is what they call a “subsidiary attack”. There will be no troops in support. We've just got to go over and keep the enemy busy while the folk on our right do the real work. You notice that the bombardment is much heavier over there. They've knocked the Hohenzollern Redoubt to bits. Personally, I don’t give a damn either way. We'll get killed whatever happens.’

We all laughed.

‘All right, laugh now, but by God, on Saturday we've got to carry out this funny scheme.’ I had never heard Thomas so talkative before.

A trench group in Loos.

Thomas went on: ‘The attack will be preceded by forty minutes’ discharge of the accessory [codeword for gas], which will clear the path for a thousand yards, so that the two railway lines will be occupied without difficulty. Our advance will follow closely behind the accessory. Behind us are three fresh divisions and the Cavalry Corps. It is expected we shall have no difficulty in breaking through.'

Photograph taken by a member of the London Rifle Brigade (1/5th Battalion, The London Regiment) of British infantry from the 47th (1/2nd London) Division advancing into a gas cloud during the Battle of Loos, 25 September 1915.

Image: HU 63277B, Imperial War Museum collection no. 9306-11.

[The attack]

An hour or so past midnight we moved into trench sidings just in front of the village. Half a mile of communication trench, known as ‘Maison Rouge Alley’, separated us from the firing line. At half-past five the gas would be discharged. We were cold, tired, sick, and not at all in the mood for a battle, but tried to snatch an hour or two of sleep squatting in the trench. It had been raining for some time.

A grey, watery dawn broke at last behind the German lines; the bombardment, surprisingly slack all night, brisked up a little. “Why the devil don’t they send them over quicker?’ The Actor [a fellow subaltern, anonymised by Graves] complained. 'This isn’t my idea of a bombardment. We're getting nothing opposite us. What little there seems to be is going into the Hohenzollern.’ ‘Shell shortage. Expected it,’ was Thomas’s laconic reply. We were told afterwards that on the 23rd a German aeroplane had bombed the Army Reserve shell-dump and sent it up. The bombardment on the 24th, and on the day of the battle itself, compared very poorly with that of the previous days. Thomas looked strained and ill. ‘It’s time they were sending that damned accessory off. I wonder what’s doing.’

[Releasing the gas]

It seems that at half-past four an R.E. captain commanding the gas-company in the front line phoned through to Divisional Headquarters: ‘Dead calm. Impossible discharge accessory. The answer he got was: “Accessory to be discharged at all costs.’ Thomas had not over-estimated the gas-company’s efficiency. The spanners for unscrewing the cocks of the cylinders proved, with two or three exceptions, to be misfits. The gas-men rushed about shouting for the loan of an adjustable spanner. They managed to discharge one or two cylinders; the gas went whistling out, formed a thick cloud a few yards off in No Man’s Land, and then gradually spread back into our trenches.

More gas blowin' in the wind at Loos.

The Germans, who had been expecting gas, immediately put on their gas-helmets: semi-rigid ones, better than ours. Bundles of oily cotton-waste were strewn along the German parapet and set alight as a barrier to the gas. Then their batteries opened on our lines. The confusion in the front trench must have been horrible; direct hits broke several of the gas-cylinders, the trench filled with gas, the gas-company stampeded.

British soldier in a gas mask.

Crew of a Vickers machine-gun in gas masks.

[The Middlesex attack]

No orders could come through because the shell in the signals dug-out at Battalion Headquarters had cut communication not only between companies and Battalion, but between Battalion and Division. The officers in the front trench had to decide on immediate action; so two companies of the Middlesex, instead of waiting for the intense bombardment which would follow the advertised forty minutes of gas, charged at once and got held up by the German wire – which our artillery had not yet cut. So far it had only been treated with shrapnel, which made no effect on it; barbed wire needed high-explosive, and plenty of it. The Germans shot the Middlesex men down. One platoon is said to have found a gap and got into the German trench. But there were no survivors of the platoon to confirm this. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders went over, too, on the Middlesex left; but two companies, instead of charging at once, rushed back out of the gas-filled assault trench to the support line, and attacked from there.

Attacking in the fog of war.

First get over your own barbed wire.

The survivors of the two leading Middlesex companies now lay in shell-craters close to the German wire, sniping and making the Germans keep their heads down. They had bombs to throw, but these were nearly all of a new type issued for the battle. The fuses were lighted on the matchbox principle, and the rain had made them useless. The other two companies of the Middlesex soon followed in support. Machine-gun fire stopped them half-way. Only one German machine-gun remained in action, the others having been knocked out by rifle- or trench-mortar fire.

Trench map repeated from above.

At this point the Royal Welch Fusiliers came up Maison Rouge Alley. The Germans were shelling it with five-nines (called ‘Jack Johnsons’ because of their black smoke) [Jack Johnson was a renowned black American boxer of the time] and lachrymatory shells. This caused a continual scramble backwards and forwards, to cries of: ‘Come on!’ ‘Get back, you bastards!’ ‘Gas turning on us!’ ‘Keep your heads, you men!’ ‘Back like hell, boys!’ “Whose orders?’ ‘What’s happening?” ‘Gas!’ ‘Back!’ ‘Come on!’ ‘Gas!’ ‘Back!’ Wounded men and stretcher-bearers kept trying to squeeze past. We were alternately putting on and taking off our gas-helmets, which made things worse. In many places the trench had caved in, obliging us to scramble over the top. Childe-Freeman reached the front line with only fifty men of ‘B’ Company; the rest had lost their way in some abandoned trenches half-way up.

The Adjutant met him in the support line. ‘Ready to go over, Freeman?’ he asked.

Freeman had to admit that most of his company were missing. He felt this disgrace keenly; it was the first time that he had commanded a company in battle. Deciding to go over with his fifty men in support of the Middlesex, he blew his whistle and the company charged. They were stopped by machine-gun fire before they had got through our own entanglements. Freeman himself died – oddly enough, of heart-failure – as he stood on the parapet.

[The Royal Welch attack]

A few minutes later, Captain Samson, with ‘C’ Company and the remainder of ‘B’, reached our front line. Finding the gas-cylinders still whistling and the trench full of dying men, he decided to go over too — he could not have it said that the Royal Welch had let down the Middlesex. A strong, comradely feeling bound the Middlesex and the Royal Welch, intensified by the accident that the other three battalions in the Brigade were Scottish, and that our Scottish Brigadier was, unjustly no doubt, accused of favouring them.

[The obliteration of 'C' Company]

One of ‘C’ officers told me later what happened. It had been agreed to advance by platoon rushes with supporting fire. When his platoon had gone about twenty yards, he signalled them to lie down and open covering fire. The din was tremendous. He saw the platoon on his left flopping down too, so he whistled the advance again. Nobody seemed to hear. He jumped up from his shell-hole, waved and signalled ‘Forward!’

Nobody stirred.

He shouted: “You bloody cowards, are you leaving me to go on alone?” His platoon-sergeant, groaning with a broken shoulder, gasped: ‘Not cowards, Sir. Willing enough. But they’re all f—ing dead.’ The Pope’s Nose machine-gun, traversing, had caught them as they rose to the whistle.

[The reprieve for 'A' and 'D' companies]

We went up to the corpse-strewn front line. The captain of the gas-company, who was keeping his head, and wore a special oxygen respirator, had by now turned off the gascocks. Vermorel-sprayers had cleared out most of the gas, but we were still warned to wear our masks. We climbed up and crouched on the fire-step, where the gas was not so thick – gas, being heavy stuff, kept low. Then Thomas arrived with the remainder of ‘A’ Company and with ‘D’, we waited for the whistle to follow the other two companies over. Fortunately at this moment the Adjutant appeared. He was now left in command of the Battalion, and told Thomas that he didn’t care a damn about orders; he was going to cut his losses and not send “A’ and ‘D’ over to their deaths until he got definite orders from Brigade. He had sent a runner back, and we must wait.

Meanwhile, the intense bombardment that was to follow the forty minutes’ discharge of gas began. It concentrated on the German front trench and wire. A good many shells fell short, and we had further casualties from them. In No Man’s Land, the survivors of the Middlesex and of our ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies suffered heavily.

My mouth was dry, my eyes out of focus, and my legs quaking under me. I found a water-bottle full of rum and drank about half a pint; it quieted me, and my head remained clear. Samson lay groaning about twenty yards beyond the front trench. Several attempts were made to rescue him. He had been very badly hit. Three men got killed in these attempts; two officers and two men, wounded. In the end his own orderly managed to crawl out to him. Samson sent him back, saying that he was riddled through and not worth rescuing; he sent his apologies to the Company for making such a noise.

We waited a couple of hours for the order to charge. The men were silent and depressed; only Sergeant Townsend was making feeble, bitter jokes about the good old British Army muddling through, and how he thanked God we still had a Navy. I shared the rest of my rum with him, and he cheered up a little. Finally a runner arrived with a message that the attack had been postponed.

[Recovering the wounded and dead]

Trench map repeated from above.

At dusk, we all went out to rescue the wounded, leaving only sentries in the line. The first dead body I came upon was Samson’s, hit in seventeen places. I found that he had forced his knuckles into his mouth to stop himself crying out and attracting any more men to their death. Major Swainson, the Second-in-command of the Middlesex, came crawling along from the German wire. He seemed to be wounded in lungs, stomach, and one leg. Choate, a Middlesex second-lieutenant, walked back unhurt; together we bandaged Swainson and got him into the trench and on a stretcher. He begged me to loosen his belt; I cut it with a bowie-knife I had bought at Béthune for use during the battle. He said: ‘I’m about done for.’ [He would survive.] We spent all that night getting in the wounded of the Royal Welch, the Middlesex and those Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders who had attacked from the front trench. The Germans behaved generously. I do not remember hearing a shot fired that night, though we kept on until it was nearly dawn and we could see plainly; then they fired a few warning shots, and we gave it up. By this time we had recovered all the wounded, and most of the Royal Welch dead. I was surprised at some of the attitudes in which the dead had stiffened — bandaging friends’ wounds, crawling, cutting wire. The Argyll and Sutherland had seven hundred casualties, including fourteen officers killed out of the sixteen who went over; the Middlesex, five hundred and fifty casualties, including eleven officers killed.

British dead caught in barbed wire defenses outside a captured German machine-gun emplacement, near Loos, September 28, 1915. Image: IWM Q 28975

Two other Middlesex officers besides Choate came back unwounded; their names were Henry and Hill, recently commissioned second-lieutenants, who had been lying out in shell-holes all day under the rain, sniping and being sniped at. Henry, according to Hill, had dragged five wounded men into a shell-hole and thrown up a sort of parapet with his hands and the bowie-knife which he carried. Hill had his platoon-sergeant there, screaming with a stomach wound, begging for morphia; he was done for, so Hill gave him five pellets. We always took morphia in our pockets for emergencies like that.

[The Middlesex lions report to their donkeys; Choate's meat pie]

Choate, Henry and Hill, returning to the trenches with a few stragglers, reported at the Middlesex Headquarters. Hill told me the story. The Colonel and the Adjutant were sitting down to a meat pie when he and Henry arrived. Henry said: ‘Come to report, Sir. Ourselves and about ninety men of all companies. Mr Choate is back, unwounded too.’

They looked up dully. ‘So you've survived, have you?’ the Colonel said. “Well, all the rest are dead. I suppose Mr Choate had better command what's left of “A” Company; the Bombing Officer will command what’s left of “B” (the Bombing Officer had not gone over, but remained with Headquarters); Mr Henry goes to “C” Company. Mr Hill to “D”. The Royal Welch are holding the front line. We are here in support. Let me know where to find you if you're needed. Good night.’

Not having been offered a piece of meat pie or a drink of whiskey, they saluted and went miserably out.

The Adjutant called them back. ‘Mr Hill! Mr Henry!’

‘Sir?’

Hill said that he expected a change of mind as to the propriety with which hospitality could be offered by a regular colonel and adjutant to temporary second-lieutenants in distress. But it was only: ‘Mr Hill, Mr Henry, I saw some men in the trench just now with their shoulder-straps unbuttoned and their equipment fastened anyhow. See that this does not occur in future. That’s all.’

Henry heard the Colonel from his bunk complaining that he had only two blankets and that it was a deucedly cold night.

Choate, a newspaper reporter in peacetime, arrived a few minutes later; the others had told him of their reception. After having saluted and reported that Major Swainson, hitherto thought killed, was wounded and on the way down to the dressing-station, he boldly leaned over the table, cut a large piece of meat pie and began eating it. This caused such surprise that no further conversation took place. Choate finished his meat pie and drank a glass of whiskey; saluted, and joined the others.

Wounded soldiers, noticeably cheerful, about to board the train that will take them away from the front and, with a bit of luck, all the way back to Blighty.

[The next attack]

We had spent the day after the attack carrying the dead down for burial and cleaning the trench up as best we could. That night the Middlesex held the line, while the Royal Welch carried all the unbroken gas-cylinders along to a position on the left flank of the Brigade, where they were to be used on the following night, September 27th. This was worse than carrying the dead; the cylinders were cast-iron, heavy and hateful. The men cursed and sulked. The officers alone knew of the proposed attack; the men must not be told until just beforehand. I felt like screaming. Rain was still pouring down, harder than ever. We knew definitely, this time, that ours would be only a diversion to help a division on our right make the real attack.

The scheme was the same as before: at 4 p.m. gas would be discharged for forty minutes, and after a quarter of an hour's bombardment we should attack. I broke the news to the men about three o'clock. They took it well. The relations of officers and men, and of senior and junior officers, had been very different in the excitement of battle. There had been no insubordination, but a greater freedom of speech, as though we were all drunk together. I found myself calling the Adjutant ‘Charley’ on one occasion; he appeared not to mind in the least. For the next ten days my relations with my men were like those I had in the Welsh Regiment; later, discipline reasserted itself, and it was only occasionally that I found them intimate.

Loos: Gas released before an attack.

At 4 p.m., then, the gas went off again with a strong wind; the gas-men had brought enough spanners this time. The Germans stayed absolutely silent. Flares went up from the reserve lines, and it looked as though all the men in the front trench were dead. The Brigadier decided not to take too much for granted; after the bombardment he sent out a Cameronian officer and twenty-five men as a feeling-patrol. The patrol reached the German wire; there came a burst of machine-gun and rifle-fire, and only two wounded men regained the trench.

Leaving a shallow trench, possibly a 'scratch trench'. Photograph taken after the time steel helmets had been issued.

We waited on the fire-step from four to nine o'clock, with fixed bayonets, for the order to go over. My mind was a blank, except for the recurrence of ‘S’nice ‘S’mince Spie, S’nice S’mince Spie… I don’t like ham, lamb or jam, and I don’t like roly-poly…’

The men laughed at my singing. The acting C.S.M. said: ‘It’s murder, Sir.’

‘Of course, it’s murder, you bloody fool,’ I agreed. ‘And there’s nothing else for it, is there?’ It was still raining. ‘But when I sees a snice s’mince spie, I asks for a helping twice…’

[Waiting]

At nine o'clock Brigade called off the attack; we were told to hold ourselves in readiness to go over at dawn.

No new order came at dawn, and no more attacks were promised us after this. From the morning of September 24th to the night of October 3rd, I had in all eight hours of sleep. I kept myself awake and alive by drinking about a bottle of whiskey a day. I had never drunk it before, and have seldom drunk it since; it certainly helped me then. We had no blankets, greatcoats, or waterproof sheets, nor any time or material to build new shelters. The rain continued. Every night we went out to fetch in the dead of the other battalions. The Germans continued indulgent and we had very few casualties. After the first day or two the corpses swelled and stank. I vomited more than once while superintending the carrying. Those we could not get in from the German wire continued to swell until the wall of the stomach collapsed, either naturally or when punctured by a bullet; a disgusting smell would float across. The colour of the dead faces changed from white to yellow-grey, to red, to purple, to green, to black, to slimy.

Loos, a shallow-trench. By this time, steel helmets had been issued.

[Baxter goes it alone]

On the morning of the 27th a cry arose from No Man’s Land. A wounded soldier of the Middlesex had recovered consciousness after two days. He lay close to the German wire. Our men heard it and looked at each other. We had a tender-hearted lance-corporal named Baxter. He was the man to boil up a special dixie for the sentries of his section when they came off duty. As soon as he heard the wounded man’s cries, he ran along the trench calling for a volunteer to help him fetch him in. Of course, no one would go; it was death to put one’s head over the parapet. When he came running to ask me, I excused myself as being the only officer in the Company. I would come out with him at dusk, I said – not now. So he went alone. He jumped quickly over the parapet, then strolled across No Man’s Land, waving a handkerchief; the Germans fired to frighten him, but since he persisted they let him come up close. Baxter continued towards them and, when he got to the Middlesex man, stopped and pointed to show the Germans what he was at. Then he dressed the man’s wounds, gave him a drink of rum and some biscuit that he had with him, and promised to be back again at nightfall. He did come back, with a stretcher-party, and the man eventually recovered. I recommended Baxter for the Victoria Cross, being the only officer who had witnessed the action, but the authorities thought it worth no more than a Distinguished Conduct Medal. [Note: a total of 21 VCs were awarded at Loos. In 1916 Anthony Eden, serving in Belgium, was awarded an MC for a similar rescue action.]

[The derelict trench]

The Actor and I had decided to get in touch with the battalion on our right. It was the Tenth Highland Light Infantry. I went down their trench sometime in the morning of the 27th and walked nearly a quarter of a mile without seeing either a sentry or an officer. There were dead men, sleeping men, wounded men, gassed men, all lying anyhow. The trench had been used as a latrine. Finally I met a Royal Engineer officer who said: ‘If the Boche knew what an easy job he had, he’d just walk over and take the position.’

Loos: after an engagement. 'Fifth element mud', said Napoleon.

Lieutenant Graves in uniform. ND.

John Kipling: death in the Killing Field

2nd Lieutenant John Kipling Image: IWM HU 123608

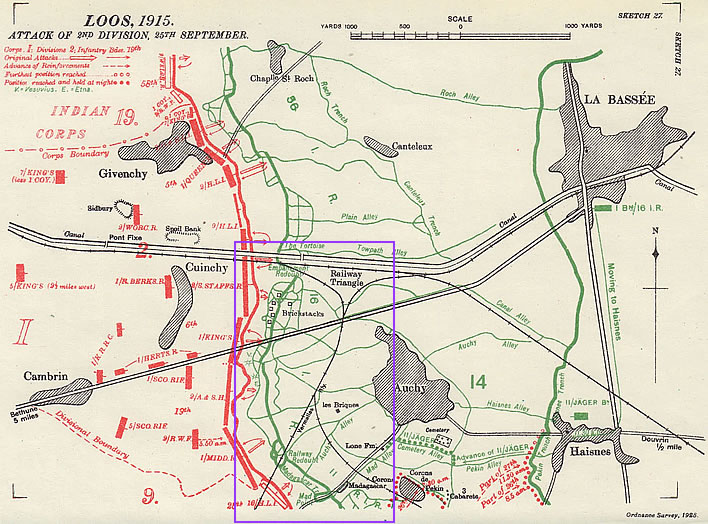

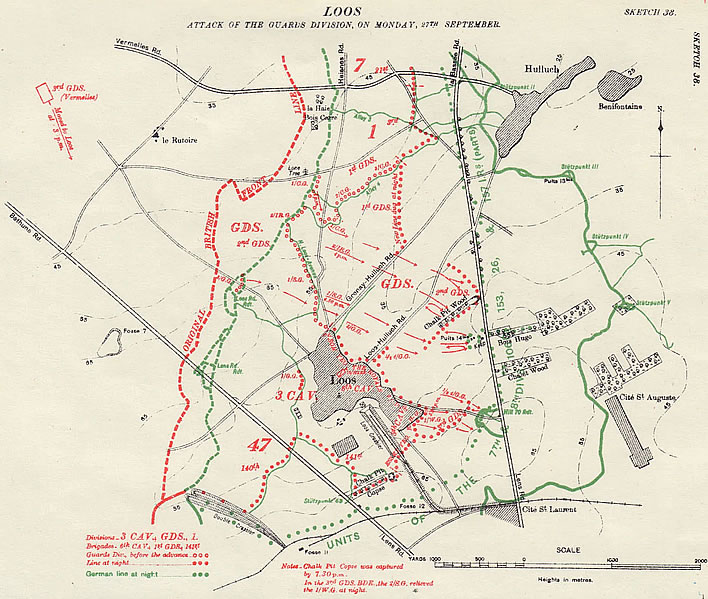

The Guards Division at Hulluch, 27 September 1915, overview.

We have no account of the fate of 2nd Lieutenant John Kipling which matches the first-person immediacy of Robert Graves' memoir of the fighting between Cambrin and Auchy. The nearest we can get is Rudyard Kiplings's reconstruction of his son's death in the regimental history he wrote as a tribute to his son. The account is in volume II of The Irish Guards in the Great War, published in 1923.

Rudyard Kipling: The action around Chalk Pit Wood

The Guards Division at Hulluch, 27 September 1915 (detail).

The 'Lone Tree' is top left; the advance of the components of the Guards Division is shown by the group of red arrows labelled 'GDS'. The main engagements took place along the Lens-La Bassée road: 'Chalk Pit Wood' at the centre of the map, Puits 14bis, (Coal-Tip 14a) just below it, then the heavily fortified 'Hill 70' redoubt.

From its trenches in front of Le Rutoire the Guards made their way slowly along congested roads and across much broken country, arriving at the selected spot – an old line of captured German trenches in front of 'Lone Tree' – just a little before midnight. Kipling adds drily:

This, as is well known to all regimental historians, was a mark of the German guns almost to the inch, and, unfortunately, formed one of our dressing-stations. At a moderate estimate the Battalion had now been on foot and livelily awake for forty-eight hours; the larger part of that time without any food. It remained for them merely to go into the fight, which they did at half-past two on the morning of the 27th September.

They were to 'push forward to another line of captured German trenches, some five hundred yards, relieving any troops that might happen to be there.'

It was nearly broad daylight by the time that this disposition was completed, and they were much impressed with the permanence and solidity of the German works in which they found themselves, and remarked jestingly one to another, that "Jerry must have built them with the idea of staying there for ever." As a matter of fact, "Jerry" did stay within half a mile of that very line for the next three years and six weeks, less one day.

The Germans had had plenty of time since their invasion to transform the terrain along the La Bassée Road and particularly between the road and the town of Loos into a killing field. They had the luxury of choosing the most defensible positions for their front and support lines. The important trenches had deep bunkers that could survive the worst bombardments; the prominences in that very flat landscape such the coal tips (Puits), the quarries and chalk pits and particularly the redoubt of Hill 70 made every Allied attack close to suicidal.

This is said to be a photograph of the British Grenadier Guards readying themselves with fixed bayonets and unusual gas masks to attack.

The plan for the attack on the 27th foresaw that at two-thirty the sector would be bombarded for an hour and a half.

At four the Second Irish Guards [John Kipling's company] would advance upon Chalk-Pit Wood and would establish themselves on the north-east and south-east faces of it, supported by the 1st Coldstream. The 1st Scots Guards were to advance echeloned to the right rear of the Irish, and to attack Puits 14bis moving round the south side of Chalk-Pit Wood, covered by heavy fire from the Irish out of the Wood itself. For this purpose, four machine-guns of the Brigade Machine-gun Company were to accompany the latter battalion. The 3rd Grenadiers were to support the 1st Scots in their attack on the Puits. Chalk-Pit Wood at that time existed as a somewhat dishevelled line of smallish trees and brush running from north to south along the edge of some irregular chalk workings which terminated at their north end, in a deepish circular quarry.

The plan turned out to be just more of the sort of wishful thinking that assumes the Germans, hunkered down in their deep bunkers, would all be killed or take the day off.

The orders for the Battalion, after the conference and the short view of the ground, were that No. 3 Company (Captain Wynter) was to advance from their trenches when the bombardment stopped, to the southern end of Chalk-Pit Wood, get through and dig itself in in the tough chalk on the farther side. No. 2 Company (Captain Bird), on the left of No. 3, would make for the centre of the wood, dig in too, on the far side, and thus prolong No. 3's line up to and including the ChalkPit—that is to say, that the two companies would hold the whole face of the Wood. Nos. 1 and 4 Companies were to follow and back up Nos. 3 and 2 respectively. At four o'clock the two leading companies deployed and advanced [. …]

They advanced quickly, and pushed through to the far edge of the Wood with very few casualties, and those, as far as could be made out, from rifle or machine-gun fire. (Shell-fire had caught them while getting out of their trenches, but, notwithstanding, their losses had not been heavy till then.) The rear companies pushed up to thicken the line, as the fire increased from the front, and while digging in beyond the Wood, 2nd Lieutenant Pakenham-Law was fatally wounded in the head. Digging was not easy work, and seeing that the left of the two first companies did not seem to have extended as far as the Chalk-Pit, at the north of the Wood, the CO. ordered the last two platoons of No. 4 Company which were just coming up, to bear off to the left and get hold of the place. In the meantime, the 1st Scots Guards, following orders, had come partly round and partly through the right flank of the Irish, and attacked Puits 14bis, which was reasonably stocked with machine-guns, but which they captured for the moment. Their rush took with them "some few Irish Guardsmen," with 2nd Lieutenants W. F. J. Clifford and J. Kipling of No. 2 Company who went forward not less willingly because Captain Cuthbert commanding the Scots Guards party had been adjutant to the Reserve Battalion at Warley ere the 2nd Battalion was formed, and they all knew him.

Together, this rush reached a line beyond the Puits, well under machine gun fire (out of the Bois Hugo across the Lens-La Bassée road). Here 2nd Lieutenant Clifford was shot and wounded or killed – the body was found later – and 2nd Lieutenant Kipling was wounded and missing. The Scots Guards also lost Captain Cuthbert, wounded or killed, and the combined Irish and Scots Guards party fell back from the Puits and retired "into and through Chalk-Pit Wood in some confusion." The CO. and Adjutant, Colonel Butler and Captain Vesey went forward through the Wood to clear up matters, but, soon after they had entered it the Adjutant was badly wounded and had to be carried off. Almost at the same moment, "the men from the Puits came streaming back through the Wood, followed by a great part of the line which had been digging in on the farther side of it."

About the operation in which his own son died, Kipling notes bitterly:

Evidently, one and a half hour's bombardment, against a country-side packed with machine-guns, was not enough to placate it. The Battalion had been swept from all quarters, and shelled at the same time, at the end of two hard days and sleepless nights, as a first experience of war, and had lost seven of their officers in forty minutes.

The denoument of the farce was bitter for the Guards Division:

The re-formed line would go up again exactly to where it had come from. No counter-attack developed, but it was a joyless night that they spent among the uptorn trees and lumps of unworkable chalk. Their show had failed with all the others along the line, and "the greatest battle in the history of the world" was frankly stuck. The most they could do was to hang on and wait developments.

They were shelled throughout the next day, heavily but inaccurately, when 2nd Lieutenant Sassoon [NB: not Siegfried Sassoon] was wounded by a rifle bullet. In the evening they watched the 1st Coldstream make an unsuccessful attack on Puits 14bis, for the place was a well-planned machine-gun nest — the first of many that they were fated to lose their strength against through the years to come.

That night closed in rain, and they were left to the mercy of Providence. No one could get to them, and they could get at nobody; but they could and did dig deeper into the chalk, to keep warm, and to ensure against the morrow (September 29) when the enemy guns found their range and pitched the stuff fairly into the trenches "burying many men and blowing a few to pieces."

They were taken out of the line "wet, dirty, and exhausted" on the night of the 30th September when, after a heavy day's shelling, the Norfolks relieved them, and they got into billets behind Sailly-Lebourse. They had been under continuous strain since the 25th of the month, and from the 27th to the 30th in a punishing action which had cost them, as far as could be made out, 324 casualties, including 101 missing. Of these last, the Diary records that "the majority of them were found to have been admitted to some field ambulance, wounded. The number of known dead is set down officially as not more than 25, which must be below the mark. Of their officers, 2nd Lieutenant Pakenham-Law had died of wounds; 2nd Lieutenants Clifford and Kipling were missing, Captain and Adjutant the Hon. T. E. Vesey, Captain Wynter, Lieutenant Stevens, and 2nd Lieutenants Sassoon and Grayson were wounded, the last being blown up by a shell. It was a fair average for the day of a debut, and taught them somewhat for their future guidance.

Some of the details of John Kipling's death can be reconstructed from the testimony of witnesses. Rudyard spoke to many of the men involved in the action, but they seem to have kept the more harrrowing parts of the incident to themselves. In the fog of battle it is only to be expected that these accounts were sometimes confused.

It appears that in the attack on Chalk Pit Wood, John Kipling had become separated from his men. According to at least one witness he was wounded in the face, his mouth shattered, and was last seen after the wood had been taken, in terrible pain, trying to dress the wound himself. He was finally found by Sergeant Farrell of the Irish Guards, who picked him up and laid him in a shell crater on the left edge of Chalk Pit Wood, believing him dead.

Finding John

Rudyard Kipling continued to use the formulaic phrase 'wounded and missing' about his son for some time, but by the end of that year it was clear that John was not in some field hospital or taken prisoner. In this, Kipling was quite correct: without an eyewitness to the death or until a body is found the phrase is technically correct, however odd it may sound. It took two years before Rudyard and Carrie heard Sergeant Farrell's account, which settled the matter for them.

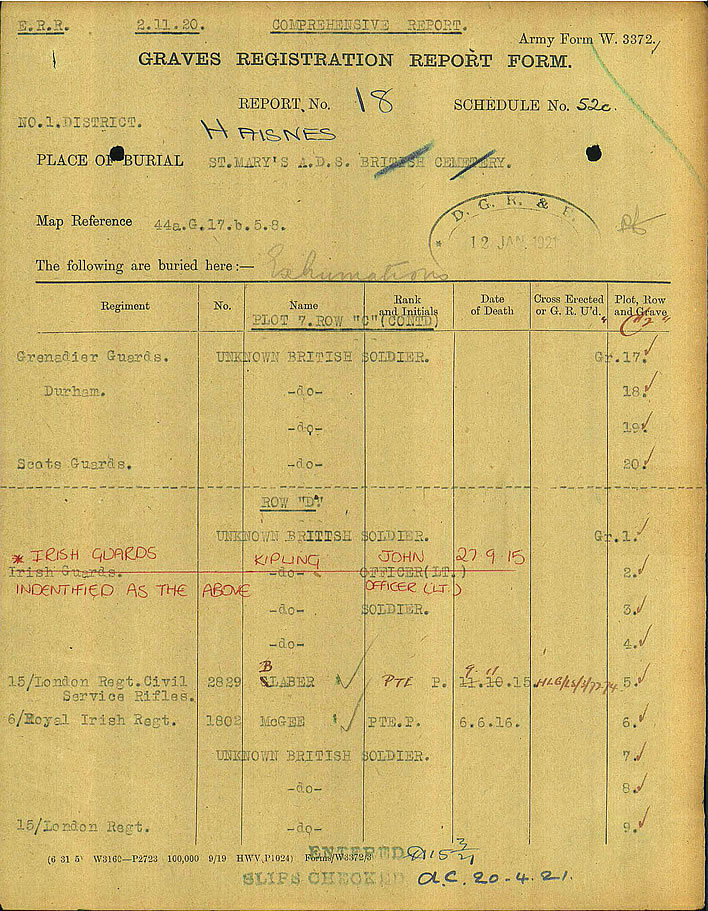

From being the grave of an unidentified Lieutenant of the Irish Guards ('A Soldier of the Great War / Known unto God') in 1919/20 to being the grave of Lieutenant John Kipling in 1992. Image: Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Around September 1919 a body of an Irish Guards Lieutenant was recovered at grid reference G.25.c.6.8. After four years in the earth only the uniform was identifiable. The body was buried in plot 7, row D, grave 2 of St. Mary's A.D.S cemetery in Haisnes. The headstone carried the text formulated by Rudyard Kipling for the graves of the unknown. 'Known unto God'. In 1992, after painstaking research, the body was identified as that of Lieutenant John Kipling. The old headstone was replaced in June 1992.

John Kipling's headstone in St. Mary's A.D.S cemetery in Haisnes.

Beginning shortly thereafter (and still continuing) there was some discussion about whether the identification with Kipling was sound. Further research appears to have confirmed the original attribution, but there are still numerous unresolved questions. Apart from doubts that the map reference given for the discovery of the body was correct (the maps of the area had been resurveyed), a further problem was that the uniform on the body had the two shoulder pips of a full Lieutenant, whereas John Kipling was nominally a 2nd Lieutenant (one shoulder pip). The suggested solution was that, although a promotion does not officially take effect until properly gazetted, which only happened after Kipling's death, it meant that the promotion was in the formal pipeline but was considered to have taken effect immediately in the field. Given the mortality rate of young officers leading their companies into battle, candidates for promotion to fill the dead mens' shoes were always in demand. Not a few recipients of field promotions were already dead by the time the notice of promotion appeared in the gazette. Even this explanation is still a matter of debate.

John Kipling's headstone in St. Mary's A.D.S cemetery in Haisnes. On either side of him is 'A soldier of the Great War / Known unto God'. Remembrance Day wreaths have been laid, the wreath at the front is from the Kipling Society.

There are numerous interested parties who continue to dispute for various reasons that John Kipling is buried here. The powers that be in such matters have stated that as far as they are concerned the matter is decided. We shall see.

Anyway, all those standing before the grave in plot 7, row D, grave 2 of St. Mary's A.D.S cemetery in Haisnes are on notice that their veneration may be misplaced. Still, whoever is down there is not undeserving of our thoughts, though his Dad may not have been the great Rudyard. As usual, only time will tell.

The war memorial in Burwash, Sussex, with John Kipling's inscription.

The memorial plaque to John Kipling in Burwash Parish Church.

The dead children

In our examination of Kipling's Just So Stories we became aware how deeply the death of their eldest daughter Josephine/Effie/Taffy affected Rudyard and Carrie, each in their own way. Now, a little over sixteen years later, the loss of John, the bright young man with a fine future ahead of him, was yet another grave blow. Harold Macmillan knew Rudyard Kipling in his later years. In his autobiography he tells us:

Rudyard Kipling I met from time to time, either at a club or by his calling in at the office to see me on some point. Two or three times I went to Bateman’s, his house in Sussex. He did no business in the strict sense of the word. All this was done for him by Mrs. Kipling or his literary agent, Mr. Watt. But he would occasionally like to get advice about such things as illustrations and format. He was very reserved, and always seemed to me a somewhat sad figure. Partly, this was due to the death of his only son in the war. I remember the devotion which he gave to his history of the Irish Guards, as a tribute to his son’s memory. But by the time I knew Kipling, he had retired from the world. Occasionally, he would lunch at the Beefsteak or dine at Grillions, where he would sometimes talk freely. He was still the supreme journalist, always interested in the master of any craft or the hero of an exciting adventure. He treated me with kindness and courtesy; but he did not unbutton himself.

Harold Macmillan, Winds of Change, 1914–1939, p. 17-18.

Parting shots

Rudyard Kipling's summary

If John Kipling had survived at Loos, the following year he would, like Robert Graves, have been sent off to the Battle of the Somme, yet another slaughterhouse into which the donkeys led their lions and which turned out to be even worse than Loos. On the Somme, the distances between the fronts were much greater than at Loos, yet for some now incomprehensible reason the British troops advancing were told to cross No Man's Land at a steady walk and not do the 'platoon rush' used at Loos – just one of the numerous reasons that the first day of the Battle of the Somme was the most deadly single day in the history of the British Army. Many of the same mistakes of wishful thinking were made that had been made at Loos (and at the first and second battles of Ypres before that). As Rudyard Kipling put it:

…it does not seem to have occurred to any one to suggest that direct infantry attacks, after ninety-minute bombardments, on works begotten out of a generation of thought and prevision, scientifically built up by immense labour and applied science, and developed against all contingencies through nine months, are not likely to find a fortunate issue. So, while the Press was explaining to a puzzled public what a far-reaching success had been achieved, the "greatest battle in the history of the world" simmered down to picking up the pieces on both sides of the line, and a return to autumnal trench-work, until more and heavier guns could be designed and manufactured in England. Meantime, men died.

Rudyard Kipling, The Irish Guards in the Great War, Volume II (1923) p. 14.

Harold Macmillan's summary

In his autobiography, Harold Macmillan gave an insightful summary of the mistakes made at the Battle of Loos, reckoning the immense toll in human lives to have achieved as good as nothing.

Inscribed by hand: 'Taken at Vermelles nr. Loos, at about 2.30 p.m. on Tuesday, Sept. 28th 1915 just before the attack on Hill 70' (Detail). Unknown source.

It is not my intention to give a general account of the Battle of Loos. This has been written in many histories. It started on 25 September with the attack by I Corps on the line between La Bassée Canal and Vermelles, and by IV Corps from Vermelles to Grenay. The attack was partially successful, but casualties were heavy, and certain positions could not be held, although the 15th the splendid Highland-Division had pushed on to Loos and even over Hill 70, but only after terrible losses.

On the afternoon of 26 September XI Corps, consisting of the Guards Division and the 21st and 24th Divisions, was transferred by Sir John French to Sir Douglas Haig’s command. Throughout that day – it was a Sunday – violent fighting took place, the 21st and 24th Divisions being used to reinforce the battle. There were heavy losses, and serious counterattacks by the Germans. Hill 70 had to be abandoned, leaving Loos exposed. The Guards Division, the third division in XI Corps, did not reach Haillicourt, nearly ten miles off, until early Sunday morning, and marched through Noeux-les-Mines to Vermelles. It was the first time the Guards Division had been in action since its creation.

But, as our regimental historian says, ‘All element of surprise had disappeared, and the Germans had had time to recover from the effects of the first blow and to collect reinforcements. It is doubtful whether the Guards Division ever had any real chance of succeeding in its attack. It had to start from old German trenches, the range of which the German artillery knew to an inch, while the effect of our own original artillery bombardment had died away.’

It was, however, decided to put in the Guards Division and try to regain as much of the lost ground as possible. The battle continued through 26 and 27 September. By the 28th it was in effect over. Lord Kitchener subsequently described it as a substantial success. Actually, what was achieved was a gain of something under a mile at a cost of 45,000 casualties [modern estimate: c. 59'000]. It is true that 3,000 prisoners and a number of guns were taken, and the official estimates – but only estimates – of German casualties were put at 50,000 [modern estimate: c. 26'000]. How far all this may have justified Lord Kitchener’s description must be left for individual judgement. However, of all these grand designs, whether failures or successes, my comrades and I knew little at the time.

Harold Macmillan, Winds of Change, 1914–1939, p. 71-72.

Put another way, it very gradually dawned on the military and political mind that the winner of a modern war is the country with the biggest infrastructure – the biggest mines, the biggest iron foundries and steel works, the biggest chemical industries, the biggest transport systems and generally the most advanced technologies. In the infrastructure battle, the little, vulnerable human bodies count for nothing. John Kipling and all the other dead and wounded of that and all subsequent wars just got in the way of the infrastructure. Human lives matter hardly at all – when hundreds of thousands are killed, the incremental value (or marginal value, as the economists call it) of the individual life is vanishingly small.

Wrapping up

Human bodies versus shells, bombs, gas and bullets. John Kipling met his end at Loos. Robert Graves survived the battle more or less intact; less than a year later he was sent to roll the die once more in the Battle of the Somme. Harold Macmillan also survived Loos, but with a bullet wound to his hand, which healed in time for him to be sent, like Graves, to roll the die once more in the Somme slaughterhouse.

They both survived that hellscape – just – but both were sent home dreadfully wounded – their dice rolled badly this time.

Graves has that special distinction, given to few, of seeing the announcement of his death posted in the casualty list in The Times. In our days of slick, technologically advanced emergency medical services, his account in Goodbye to All That of his injuries and their treatment makes for a sobering read for a modern. Macmillan, who lay badly wounded in a shell crater for a day before being retrieved, needed four years of doctoring to get him back to some sort of normal.

Despite the batterings their bodies had received in the war, Graves (90) and Macmillan (92) both lived long, outstandingly productive lives. John Kipling, to whom we pay our respects today, died at eighteen, leaving a promising life unfulfilled.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!