Schubert's syphilis revisited (yet again)

Posted on UTC 2026-02-04 09:12

This is a review of a paper published last year, One night with Venus, a lifetime with mercury, which was published on 29 April 2025 [Fischer, L., Hann, S., Amory, C. et al. 'One night with Venus, a lifetime with mercury'. Wien Klin Wochenschr 137, 438–445 (2025), DOI, which I shall refer to from now on as ONV. This paper contains many procedural and factual errors. As far as I can tell, among the six(!) authors of the paper there was no Schubert scholar or even an Austrian historian (very plentiful at the moment).

The purpose of the ONV paper can be stated very simply. In 1823 (or very late in 1822) Franz Schubert (together with his then bosom-buddy Franz Schober) picked up syphilis and underwent a course of treatments with mercury. Mercury hangs around in the body and traces of it are deposited in human hair. If Schubert's hair contains mercury, we have evidence that the syphilis episode took place and was treated in the customary manner.

Background

We don't know anything about the fun bits. Perhaps it was a Christmas or New Year's present from the wealthy womaniser Schober to his cash-strapped and highly introverted little friend to allow him to finally break his duck; perhaps Schubert had just sold a composition. Who knows? The two best mates, well oiled and adrift in the imperial capital, shared what would turn out to be a life-changing experience, certainly for Schubert.

Prurient minds like mine wonder whether they each had their own lady of the night or whether they indulged in that great male bonding act of sharing the woman. Perhaps Schober got a discount. Was it a one-off, or had they picked up the habit? 'One night with Venus' is a bit of an assumption. The 'Schubert was gay' evangelists should reflect that, if the two halves of the 'Schobert', as the pair came to be called, were really gay, they would not need to be out on the town looking for love interest. Who knows?

Such vulgar observations may have genteel Schubert fans reaching for the smelling salts, but we cannot ignore the fact that the Act of Darkness a.k.a. the Beast with two Backs, with all its absurdities and ridiculousness was in there somewhere. A few weeks later the ulceration appeared: they had rolled the dice and lost, at least in the first instance.

Schubert went for treatment to the Vienna General Hospital with the usual medication involving principally concoctions of mercury.

As far as I know we have no information about Schober's treatment; we might suppose that as a relatively rich man he could afford home doctoring and didn't need to slink in and out of the syphilis ward of the General Hospital, but that is just a supposition.

We know of Schubert's infection despite the discretion that surrounded this sexually transmitted disease. Even then the cause was inescapably clear – no innocent toilet seats were involved in the acquisition of this bacterium.

The need for discretion during a very uptight Catholic period in Austria meant that little was written or discussed about Schubert's illness, but we know with a fair degree of certainty that this episode took place. Given Schober's louche reputation amongst those who knew him, even from his school days, a dose of syphilis would surprise no one.

Schubert seems to have lain low for a while, moved his residence and taken to wearing a wig (although I am not completely convinced about this last point); Schober astonished his friends by taking himself off to join a theatre troupe in Breslau (now Polish Wrocław), in which wig-wearing was part of the job and possibly many of his colleagues had probably had a brush with the disease.

We also know nowadays what Schubert could not have known, that in about three-quarters of cases the infection runs its course over a few months and then the symptoms and the bacteria disappear. The fate of those in the unlucky quarter is, at its worst, horrible and the fear of the disease was widepread.

Goethe (1749-1832) had a deep-seated terror of the disease which seems to have kept his libido in check whenever opportunity knocked; Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) believed the disease that confined him to his 'mattress-grave' during the final part of his life was syphilis (the modern opinion is multiple sclerosis); it is generally accepted that Robert Schumann's (1810-1856) mental disintegration during the last years of his life was a result of syphilis; Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) died 55 years old, after ten years of progressive mental degeneration, until very recently also thought to be the result of syphilis.

It appears to us now that, though Schubert and Schober both lost on the first roll of the dice (they were infected), they both seem to have won on the second (they were cured). Nevertheless, we can understand how Schubert seems to have been haunted in the years following 1823 until his death with the thought that the syphilis was still present within him and was the source of his frequent headaches and other malheurs. Was all the manic activity in his later years the act of a man who imagined that his great mental faculties were on a short lease?

There is another aspect of Schubert's mental state following his infection that would hardly cheer him up. The general opinion at the time was that such diseases were the earthly punishment of the lustful. In his correspondence with his brothers during his first stay in Zseliz (July to November 1818) he ranted against the bigotry of the local rural priest, who had thundered from the pulpit over the sins of a man and a woman getting it together after an evening in the tavern.

Now, after his own experiment with the joys of wild sex, he might feel that he had received his just desserts, just like the preachers warned him. Was he stewing in guilt? In order to understand this feeling we moderns have to empty our heads of all our modern knowledge: it would be at least a quarter of a century after Schubert's death that germ theory, which provided a causal explanation for the transmission of infectious diseases, entered the medical mainstream.

In this respect syphilis was particularly mysterious. Whereas the characteristic ulceration of the male genitals was highly visible, in the female the ulcers were not external – the woman herself might have had no idea that she had been infected. He revisited Zseliz (May to October 1824) presumably when the symptoms had died down. I wonder if he recalled the sermon he had heard there six years before. Certainly for the short, dumpy, introverted composer, frequently strapped for cash, the syphilis episode was one further reason that no sensible woman would consider him as a mate.

Schubert died on 19 November 1828. We can say with some certainty that the cause of death was typhoid fever. Whether the syphilis of 1823 was a factor in his succumbing to typhoid fever five years later we shall never know – but it doesn't really matter, since typhoid fever (which had also killed his mother) is quite capable of killing someone without assistance from some other little helper.

Our simple understanding of Schubert's death and his brush with syphilis is capable of being messed up with all kinds of other speculations – for example, that the beatified Schubert never caught syphilis, or that he was not treated, or that he suffered for the rest of his life from the disease and so on and so forth.

It would be of interest, therefore, to have some solid evidence of Schubert's treatment for syphilis if only to add a bit more substance to the received opinion. This is where ONV comes in, which attempts to demonstrate using hair analysis that Schubert had substantial amounts of mercury and lead in his system, in quantities that could only have come from a mercury treatment. It does that, in fact, but manages to sabotage its own success through a surprising lack of rigour.

The article is so error-ridden that going through it line-by-line to correct all the mistakes and misstatements would require more energy than I am willing to give. Let's do it thematically, an approach that will probably make more sense to readers anyway.

Provenance

ONV uses two hair samples; one that is in the possession of Raimund Hofbauer, a descendent of Schubert (the composer was his great-great-great-uncle, to be precise), the other is sealed in a glass display medallion in the Ignaz Weinmann collection (at the time of writing of the paper in the Atzenbrugg museum).

Now the most critical part of using such artefacts in research is providing a credible provenance for the artefact in question. It is nice when we can do this with 100% certainty, but often we have to take what we know and add a little bit of common sense to generate a provenance. The value of the analytical results from the artefact can only ever be as good as the artefact's provenance.

The provenance of the Hofbauer sample

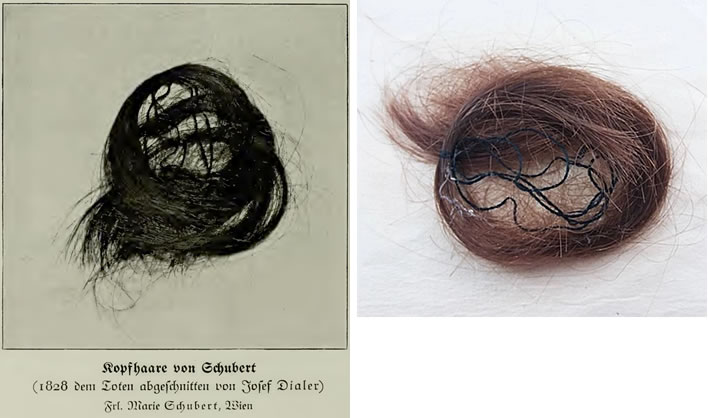

Curls of Franz Schubert (Private possession of Raimund Hofbauer, Kritzendorf, Lower Austria) Image: Fischer et al.

Under the heading 'Provenance of Schubert's hair' this is what the ONV authors tell us about the provenance of the Hofbauer hair samples:

In the following section, provenance and proof of authenticity of the samples is described briefly. More information can be found in the supplementary section.

Unfortunately there is no further information about provenance in the 'supplementary section' (which scarcely exists), so we have to rely on what we are told here.

Hair samples of curls which are currently in the private possession of Raimund Hofbauer (Kritzendorf, Lower Austria) and preserved in a sand-colored envelope have also[sic] been provided for analysis. An inscription, written in German current handwriting (style approximately from 1850) declared the authenticity: 'For Mrs. Mitzi Schubert, retired teacher, curl from Fr. Schubert. By kindness — a synonym for delivered by messenger at the time' [translated].

This is not a valid provenance at all. This text has not 'declared the authenticity' of the artefacts. We are not told who sent this; we don't know when it was sent – versions of Deutsche Kurrentschrift were in use for centuries and there were many regional variants, so 'style approximately from 1850' does not qualify as a date – how 'approximate' is this guesswork, 1840? 1860?; we are not told who 'Mitzi Schubert' was, we are not given the text in the original language but have to make do with a translation by some person unknown which mysteriously includes the word 'kindness' as a postal service.

That something was sent by an unknown person to someone called Schubert at some unspecified date does not make the hair sample authentic – and it is actually quite amusing that six credentialled scientists think it does.

Herr Hofbauer himself was kind enough to supply me with some more information, including the German original of the mangled translation. According to him, the text was written by the great Austrian Schubert scholar Otto Erich Deutsch (1883-1967). He had borrowed the two locks of hair for an illustration in his work Schubert. Sein Leben in Bildern. If this is correct – and there is no reason to doubt this – then the date of dispatch was 1913 or thereabouts. Forget 1850 Kurrentschrift. The German text is as follows:

An Frau Lehrerin i.R. Mitzi Schubert durch Güte.

To retired teacher Ms. Mitzi Schubert by hand.

Herr Hofbauer was kind enough to supply me with some private details of 'Tante Mitzi' ('Aunt Mitzi'), Marie Schubert, who was only two generations removed from Schubert's artist brother, Carl (1795-1855) via Carl's son, Heinrich Carl Schubert (1827-1897). That by around 1913 she was a retired teacher fits the timeline perfectly.

The lack of the German original and the odd word 'kindness' in the translation caused me some headscratching. Once we have the German text the matter is clear: durch Güte is an expression the sender wrote on a letter that said it was being delivered in person by the writer or through some intermediary such as a friend or courier. In English we would write 'by hand'. With such a precious object we would be surprised if Deutsch had simply entrusted the packet to the normal post. I have seen examples of letters bearing this instruction from as late as the 1930s.

I stumble over the English phrase 'curl from Fr. Schubert'. The phrase seems wrong – one wouldn't advertise to the world the contents of a packet such as this, even when privately transported. Is this a 'helpful decoration' from the translator? After further enquiries, it turns out that this phrase – as we suspected – is not part of Deutsch's address line, but was written apparently by Mitzi on the envelope after receipt: Locke von Franz Schubert, 'curl from Franz Schubert'. Just running together Deutsch's address line and Mitzi Schubert's memo line – written in differing hands – to make a single attribution text is unacceptable.

So, in sum, we can provide an approximate but reliable date, and the context: a credible name of the sender, a credible name of the recipient. And for the avoidance of all doubt we have this, the photograph of the ringlets that appeared in Deutsch's work, side by side with the modern photograph reproduced in ONV.

Left: An illustration of Schubert's hair from O.E. Deutsch, Schubert. Sein Leben in Bildern, 1913, p. 38. Right: Photograph of Schubert's hair (Hofbauer sample) from ONV.

Now that's a provenance.

Our joy would be unconfined were it not for Deutsche's caption 'cut from the dead Schubert by Josef Dialer in 1828'. In fact, Herr Hofbauer tells me, Deutsch is in error here.

Herr Hofbauer has forbidden me to reproduce here the statement he sent to me in an email, but in essence he states that the ringlets of hair were taken in 1824 at a time when his hair was falling out 'in clumps' as a consequence of the treatment with mercury.

We can even add to the credibility of this provenance when we note the presence of roots on the hairs (mentioned in ONV). Had the hairs been cut post-mortem there would have been no roots.

Our contentment doesn't last long, since for some reason I do not understand, the ONV team carried out a DNA analysis on two hairs from the Hofbauer sample. After much expensive hacking about in contaminated DNA, they came to the conclusion that:

Despite the lack of maternally related reference samples from a (living) relative of Franz Schubert, we can assume that the two curls in Raimund Hofbauer’s possession come from one and the same person

We have to run this statement through our sanity parser in order to extract something from it, since it consists of two independent and quite unrelated statements bound together by the otiose conjunction 'despite': 1) we don't have any DNA samples from the maternal Schubert line – and then the unsaid part, paraphrased – so we cannot prove that this hair came from Schubert, just that they both came from the same person (whoever that might be!). To which my answer is: since you knew this before you ran the tests, why bother?

The unrelated statement 2) is that the characteristics of two hairs taken from the Hofbauer sample match, meaning that they came from the same person. In view of the provenance we have now worked out for them, the shock would have been if they hadn't come from the same person. Then again, if they are serious in investigating the homogeneity of the Hofbauer sample, they would have to perform this test on a statistically meaningful sample of all the hairs in the two bunches in the source, which would certainly cause more destruction than Herr Hofbauer would agree to.

The Weinmann collection sample provenance

Photograph of the medallion from the Ignaz Weinmann collection with Franz Schubert's hair. Light-colored bronze, diameter 64 mm, circular engraving. Image: Fischer et al.

For some reason I do not understand, the ONV team introduced a second source of hair, a few strands mounted in a glass container from the Ignaz Weinmann collection, which has its permanent home in the Vienna City Library. My bafflement at this pointless complication is increased by the poor quality of the sample:

Hairs from the medallion (Weinmann/Vienna City Library), on the other hand, showed a severe loss of scale structure of the surface and a fluctuating hair thickness between 45 and 75 μm. Extensive microbial contamination and spongy, fine-pored matrix loosening was found both on the surface and in the medullary substance.

We have managed to establish with a high degree of certainty that the Hofbauer hairs were collected in 1824 (possibly 1823), right in the middle of Schubert's syphilis treatment. The ONV team doesn't tell us when the Weinmann hairs were acquired. I would assume that they were clipped post-mortem, that is, in 1828, around four years after the treatment in 1823/24, but they may be the degraded sample from the exhumation. ONV is not clear on this point. To be frank, I have got to the point where I don't care any more.

The ONV team has not even attempted to provide a provenance for the Weinmann hair. Perhaps they think that just because it is in a museum all that tricky provenance stuff has already been resolved. Simple people!

Then for me, with my limited brainpower, the project descends into an incomprehensible chaos from the point where hair samples are taken and labelled. I have tried making notes and drawing diagrams, but still get no further. Perhaps our sparky readers can make more sense of it all. Here's the acquisition of the test material from the Hofbauer samples:

A few single hairs were removed with sterile and pre-annealed tweezers, transferred into small paper envelopes and labelled accordingly: Schubert A1.W, Schubert A2.W, Schubert A3.W, Schubert B and Schubert B 1.W.

To which we can only ask: How many is 'a few'? The summary speaks of 'three strands of Franz Schubert's hair'. Now we have five packets. What do these designations represent? Then, from the Weinmann source, we have the following:

Two single hairs of the loose strands of approximately 3 and 4 cm in length were removed from the medallion individually using sterile and annealed splinter tweezers and subsequently transferred in paper envelopes labelled as follows: Schubert C 1—tox and Schubert C 2—DNA.

Don't bother trying to memorise the names of these samples, they are hardly ever used again. From now on we have 'hair A', 'hair B' and 'hair C', and a little later hair segments 'A‑S', 'B‑S' and 'C‑S' – and sometimes other variants which I cannot be bothered to enumerate.

This may sound like nitpicking, but it is actually a very important matter for this research project. Furthermore, my inner pedant (always close to the surface) rebels at 'annealed' and 'pre-annealed'. Annealing is a process that uses high temperatures to change the properties of metal. I think they mean 'autoclaved', that is, sterilised in an autoclave. Stating 'sterile and annealed' [sic, autoclaved] is a duplication.

The Weinmann sample now seems to disappear. However, if we were paying attention when reading the summary we would recall that:

The two hair samples presumably taken from the deceased’s head showed matching molecular biological parameters, while the sample taken 35 years after his burial did not contain any usable DNA.

I have no idea what they are talking about here, no idea at all. Are the 'two hair samples' from the Hofbauer or the Weinmann sources? What is this sample taken 35 years after is burial? Is this the Weinmann, or some other source we have not been told about?

Worse still, the ONV authors simply state in the summary that the 'two hair samples [were] presumably taken from the deceased’s head'. Given what we now know of the provenance of the Hofbauer hair, this statement is completely incorrect. Is the ONV team under the impression that the Hofbauer sample was taken post-mortem? In which case they have to explain how hair snipped from a corpse can still have roots. In which case, too, their presumption that the samples dating from 1824 date from 1828, means that their interpretation of their measurements is four years out.

Already confused, the reader has now to trudge through a lot of hypertech-talk about mitochondrial (mt) DNA analysis, hair analysis by LA-ICP-SFMS and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Which is fair enough, it is what the paper is about – it's not the author's fault that I do not understand a word of this apart from occasional highlights such as 'Pritt non-permanent double-sided tape'.

So let's have a look at what emerges from this complexity.

Interpreting the results

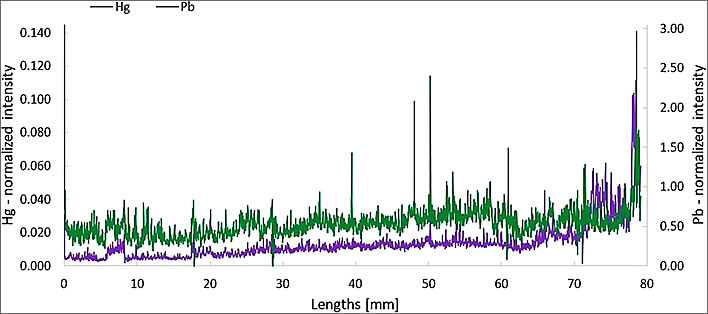

Variations of relative concentrations (34S normalized intensities) of Hg and Pb in a hair sample of Franz Schubert (Schubert A 3.W). The hair sample was ablated from close to the root (0 mm) to the end of the hair (surface scan), reflecting exposure of toxic metals during approximately the last 8 months of his life. Image: Fischer et al.

Well if this is hair 'Schubert A3.W' from the Hofbauer source (there is a root), we can say that the interpretation 'reflecting exposure of toxic metals during approximately the last 8 months of his life' is completely wrong. It represents the levels of 'toxic metals' in the middle of his syphilis treatment, at the point his hair was 'falling out in clumps'.

In order to understand these plots you have to know that on the x-axis (length), zero is the hair root and the value on the right is the length of the hair. We are told (rather obliquely) that this length scale represents between five and eight months of hair growth.

Now if this hair had been taken post-mortem, as the authors assert, and assuming eight months growth, the scale therefore runs left to right from 19 November 1828, the moment of Schubert's death, to (say) eight months before, that is March 1828. In this respect, Schubert fans will think of Schubert's first and last concert, on 26 March 1828 – except eight months is just guesswork, remember.

But we know with some certainty that the samples were collected in 1823/24 in the middle of his treatment, so they represent in reality an eight month span during this period.

The spike around the 80 mm mark may be inconvenient and thus can be dismissed as an outlier – possibly. There are no error bars (the lack of which I find quite puzzling, actually, given the noisiness of the plot and the numerous outliers), so we have no idea whether the variations or the overall slight slope on the graph are significant. I am not sure at a glance which curve is Hg and which is Pb. From the other graphs it seems that Hg is purple and Pb is green. If we discard the early spikes we are forced to conclude that not very much changed in this period.

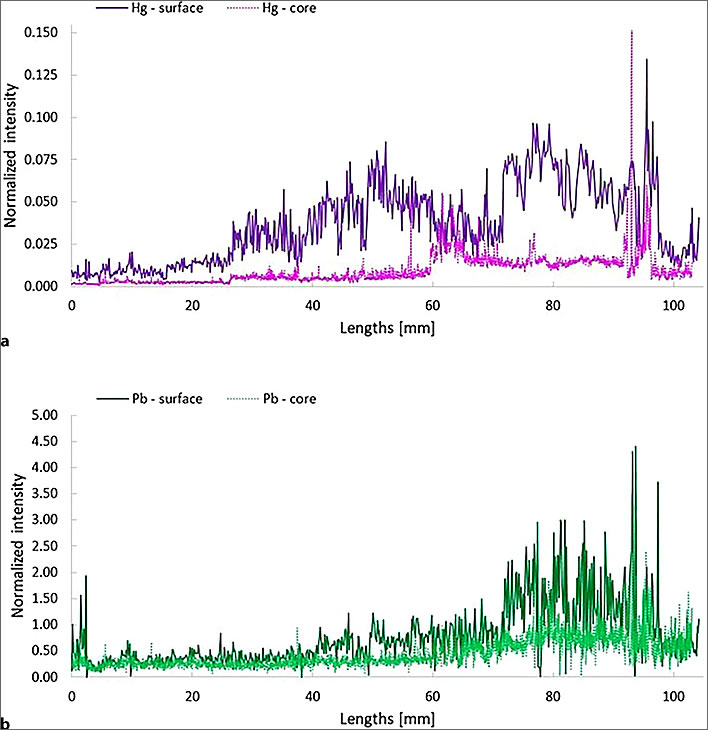

Yet more measurements. As a layman in such matters, I find it difficult to reconcile the following plots with the previous plot. Try as I might to get my decrepit brain to sum the core and surface plots in a way that they produce the combined plot in the previous graph, I cannot do it.

Variations of relative concentrations (34S normalized intensities) of Hg (a) and Pb (b) in the surface (cuticle) and the core of a hair sample of Franz Schubert (Schubert B). The hair sample was ablated from close to the root (0 mm) to the end of the hair, whereas the second scan was performed with an offset of the z‑axis (10 µm) to laser scan the inner part of the hair Image: Fischer et al.

As we have noted, the ONV team imagines that their results arise from 1828. They therefore have to think of a way of making them relevant to poor Schubert being slathered with mercury compounds in 1823/24. It means that we poor readers have to cope with a lot of scientific abracadabra and good old sophistry:

Elevated mercury levels in the hair samples of Franz Schubert were evenly distributed over the entire length of approximately 7–10 cm, reflecting approximately the last 10 months of his life. There is no indication regarding mercury-based medication within the last few months preceding his death and medicines taken 2 weeks before his death were not specified on the prescription [5]; however, in cases of typhoid fever (formerly known as “nervous fever”), doctors would not have prescribed medication containing mercury. Furthermore, a significant increase of the relative mercury concentration would have been observed in the hair samples over the last 2 weeks, corresponding to 0–5 mm of lengths. Elemental/metallic mercury affects all body tissues via the blood circulation, consequently, it bioaccumulates in the central nervous system, the kidneys and, due to the liposolubility, it crosses the blood-brain barrier and accumulates in the brain, particularly if it is inhaled. The biological half-life of mercury is approximately 30–60 days, whereas in the brain, it might be 20 years or even more as oxidized elemental mercury strongly binds to the Se and SH groups of biological ligands [27, 28]. Constant release of bioaccumulated mercury from body tissues into the bloodstream and incorporation into the hair matrix over many years could explain the elevated relative concentrations in the hair of Franz Schubert.

When you read this argumentation carefully, it becomes clear that in invoking a persistent temporal presence of mercury and lead in hair samples the team destroys the validity of its own work. If raised levels of these two elements in any particular sample could arise from exposure that occurred at any time between the present and the previous 20 years, then the temporal resolution of the situation can never be finer than 20 years.

And then comes the baffling statement '[t]here is no indication regarding mercury-based medication'. If we assume that the team is talking about one of the Hofbauer hairs, since they were taken in the middle of Schubert's medication programme, the researchers have just destroyed the premise of their work. Astonishing. Let's be kind: if by 'indication' they mean 'evidence in the data', they are quite wrong; if they mean 'no external evidence that Schubert was being medicated' (don't forget: the team thinks it is looking at 1828, not 1823/4), then they are also quite wrong.

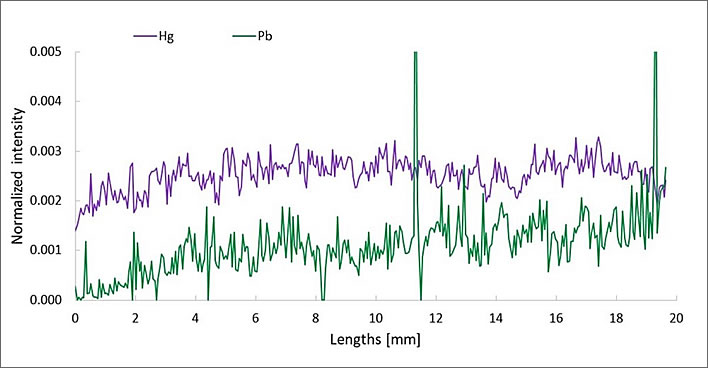

Figure S1: Relative concentrations (34S normalized intensities) of heavy metals in a single hair (cuticula) of a male non-smoking individual. The hair sample was ablated from the root (at 0 mm) to the end of the hair. Image: Fischer et al.

The results from the normal person (mysteriously consigned to the section 'Supplementary Information') are plotted to a much larger scale – the y-axis of the 'normalized intensity' runs from 0.000 to 0.005. The x-axis of the length is also much shorter than that of the Schubert samples (20 mm instead of 80..100 mm), meaning that for the normal person the intensity is at least a factor of 10 smaller than Schubert's levels and the time span represents only three to four weeks of growth. The researchers could have been kind to the weary brains of their readers and presented all their results on the same scales, since this is in effect the crux of their argument. As it is, readers are left to study the y-axes on their own.

Improper comparison sample

Comparing Schubert's results with those from a contemporary male strikes me as being a waste of time. The environmental differences between the 1820s and the present are so enormous and multifactorial that a comparison of the two is both meaningless and misleading. The only relevant comparison would have been with hair samples from several of Schubert's contemporaries. Of course this would be more difficult, but I am sure that Austria is not short of post-mortem hair clippings from the early nineteenth century.

I had to read the researchers' concluding remarks a few times before I was able to decipher what they were saying. Despite my efforts, I am not convinced that I have understood their statement. The reader must judge:

The continuous but on average 50-fold increase of the relative mercury concentration and the up to 2000-fold increase of the relative lead concentration in Schubert’s hair in the last 10 months before his death indicate a massive heavy metal exposition years before with subsequent long-term excretion.

Apart from not making any sense in general, the difficulty with this screwed up statement seems to be that they are using the word 'increase' when in fact they mean the word 'difference'. I have no idea what 'a continuous … 50-fold increase' is. According to their own data, Schubert's 'pollution' did not increase in the months before his demise, if anything, it decreased. The alarming '50-fold' and '2000-fold' statements are in relation to the levels found in a modern non-smoker (I think). This level of drama is achieved by taking the pronounced spikes which, we were told, were treated as outliers and ignored. And, lest we forget, they think they are looking at 1828 when in fact they are looking at 1823/24, totally invalidating every conclusion they draw.

And what was it they said a few paragraphs before this? 'There is no indication regarding mercury-based medication within the last few months preceding his death'. The word 'indication' makes the reader think that this is in the scan results. Allow me to translate: 'There is no evidence that Schubert was being medicated with mercury…' – whereas he very much was being treated with mercury. Now we are told that the levels of mercury and lead are many times higher than the 'normal' case. I leave it to the reader to resolve all the contradictions in this summary.

If the ONV team had just got the date of origin of the Hofbauer samples correct, none of this wiggling around would have been necessary. One simple measurement showing the absolute values of mercury and lead around 1823/24 would have been sufficient to prove the reality of Schubert's syphilis cure.

If we date the Hofbauer samples correctly (1823/24) then we can help out the ONV team with another puzzle they faced:

As shown in Fig. 4a, b and the relative concentrations of mercury and lead were higher in the surface (cuticle) than in the core of the hair samples and vary similarly over time. Lower metal concentrations in the core compared to the cuticle are in accordance with previous findings [34]; however, the reason for this peculiarity remains unclear. Variations of mercury in the outer and inner area of sample B (see Fig. 4a, in particular in the section from 60–70 mm) do not show the same variation.

If we imagine poor Schubert being slathered with mercury and lead ointments and even perhaps sitting in a mercury steam bath, it would come as no surprise that the outer sheath of the hair is richer in toxic metals than the inner core.

The dating of the samples has two consequences. Firstly, when we know that the levels of toxic metals in Schubert's hair were high in 1823/24, the thesis of Schubert's syphilis infection and resultant treatment goes from highly probable to certain, which is what the research set out to show.

However, before the researchers light up the cigars and break out the prosecco, they should realise that what they have done by mis-dating the samples as immediately post-mortem is that they have given ammunition to those who want to believe that Schubert died as a result of his 1823 syphilis and/or the associated mercury treatments that were still spooking around in his body.

The ONV team should retract this shambles and go away and have a little think about it.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!