The antennae of the race

Richard Law, UTC 2016-08-15 07:41

Cerebral hygiene, anyone?

Most of The Cantos was written after 1924, when Pound moved from Paris to Rapallo. In that small Italian town he lived and worked in relative isolation. During his time in London and Paris he had thought that the spirit of the new age was a metropolitan spirit. All the '-isms' of that time were essentially metropolitan movements. The rustics and Romantics were of an earlier age and the kitsch countryside of the Georgian poets was popular but passé. By the mid-1920s Paris had lost its charms for him and his health would benefit from a warmer and more rural climate.

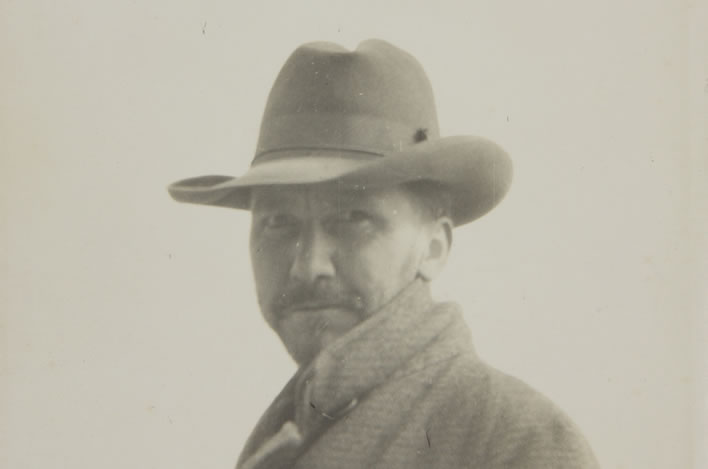

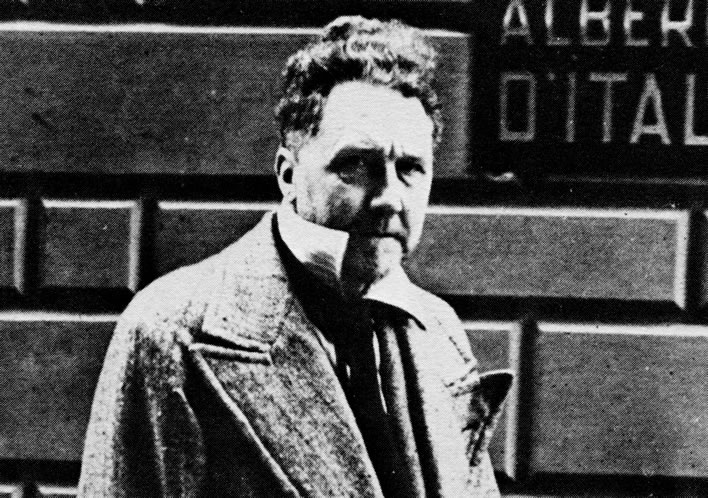

Ezra Pound in 1929. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 54, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate

Describing Pound's personal life from this time as a moral mess is an understatment: he had a wife and a live-in mistress who hated each other – their mutual dislike does not come as a surprise; his son by his wife was sent to England to be looked after by his wife's mother; his daughter by his mistress was fostered out and later sent to a school in Switzerland.

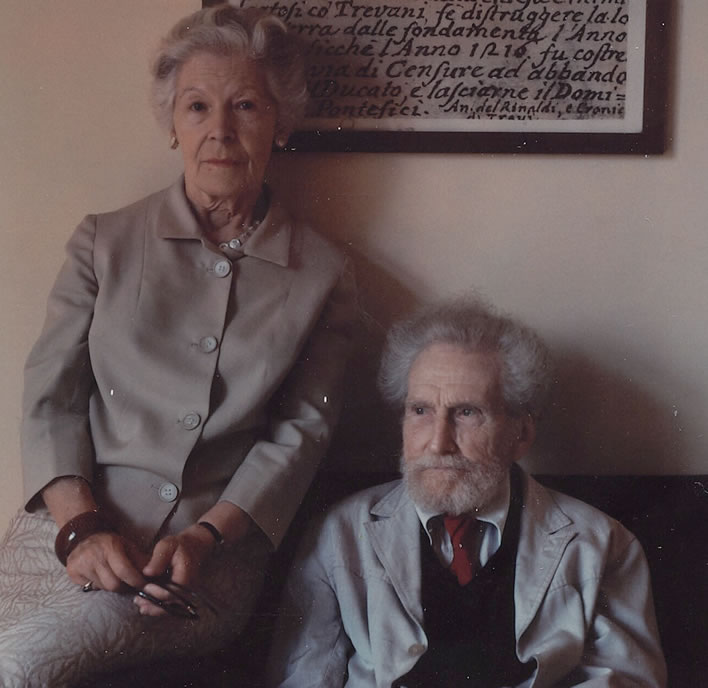

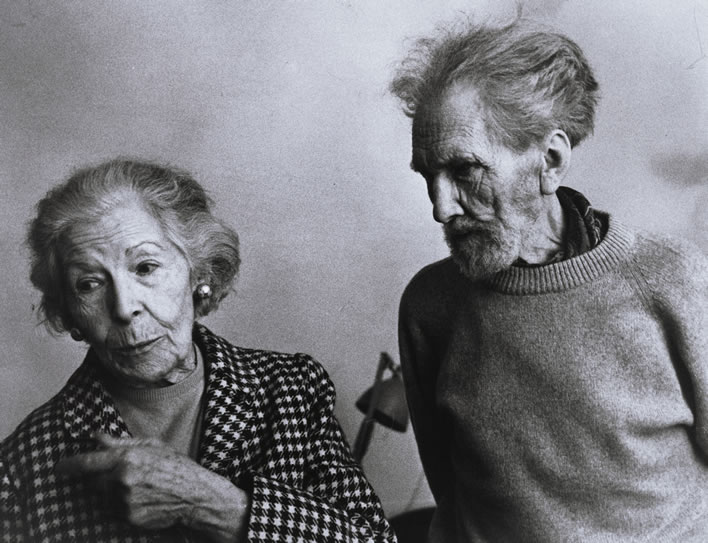

Ezra Pound and Olga Rudge in Venice, 1923. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 54, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate

Ezra Pound and Olga Rudge, undated Polaroid photograph. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 241, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate

Ezra Pound and Olga Rudge in 1971. Image: Beinecke Library, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate

In those fifteen years in Rapallo Pound completed his personal journey from loud eccentric to lunatic.

In terms of his work, the cantos he wrote during that period, C31-C73, can only be described as unhinged. Although they contain occasional patches of luminous poetry, the further the reader goes in them the further the hinge detaches from the door.

In terms of his life during this period, his opinions, lacking any serious intellectual counterweight, became as unhinged as his poetry – quite bonkers, in fact. A serious psychiatric assessment is outside our scope: if you find the terms 'insane', 'unhinged' or 'bonkers' unsatisfactory then you will have to paddle your own path through this vale of tears – you will still arrive at the conclusion that Pound's political, intellectual and social ideas were bonkers.

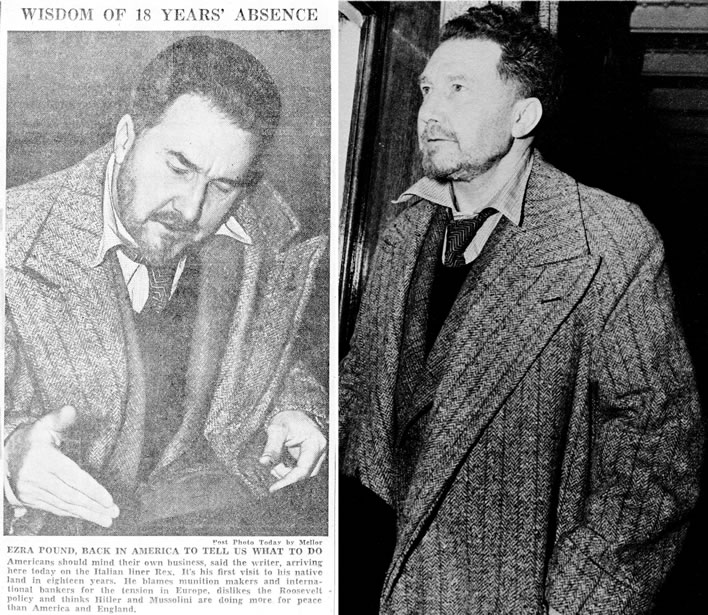

Left: Newspaper clipping from the New York Post reporting Pound's arrival to the USA in 1939. The caption hits a nicely ironic tone: 'EZRA POUND, BACK IN AMERICA TO TELL US WHAT TO DO. Americans should mind their own business, said the writer, arriving here today on the Italian liner Rex. It's his first visit to his native land in eighteen years. He blames munition makers and international bankers for the tension in Europe, dislikes the Roosevelt policy and thinks Hitler and Mussolini are doing more for peace than America and England.' Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 43, Yale.

Right: Pound on board the liner Rex arriving in New York in 1939. Hope springs eternal.

He could have saved himself from what was to come had he remained in the USA when he went there briefly in 1939, but he was too far gone. He returned to Italy and spent the war-years happily on the wrong side, supporting Mussolini and Hitler, even broadcasting on Rome Radio. He was a fascist who managed to be simultaneously an old-school Jeffersonian democrat yet fully support the Führerprinzip in its incarnations in Mussolini and Hitler. He was an antisemite, mainly against the 'big jews' rather than the 'little jews' – the latter were a little less harmful.

Ezra Pound the radio broadcaster in front of his hotel in Rome in 1942. Between 1941 and his arrest in May 1945 he earned 153,060 Lire from the Italian Ministry of Culture, presumably for his broadcasting activity. Given that his copyright earnings were all trapped abroad during WWII a crust had to be earned somehow. Image: source unknown at present.

Our thoughts go out to the poor underling from the US monitoring service who was detailed to transcribe these crackly ravings. The jumble of obscure, unrelated scraps in half a dozen languages was clearly a challenge. Pound apologists choose to chortle at the ignorance of the transcriber rather than the lunacy of the speaker.

Mussolini was shot and strung up on 28 April 1945. A few days later Italian partisans arrived at Pound's house and took him away. His American citizenship and his obviously defective mental state saved him from joining the shade of Il Duce. After the partisans released him he surrendered to the safe-keeping of the nation he had unceasingly traduced during the previous 20 years, the United States.

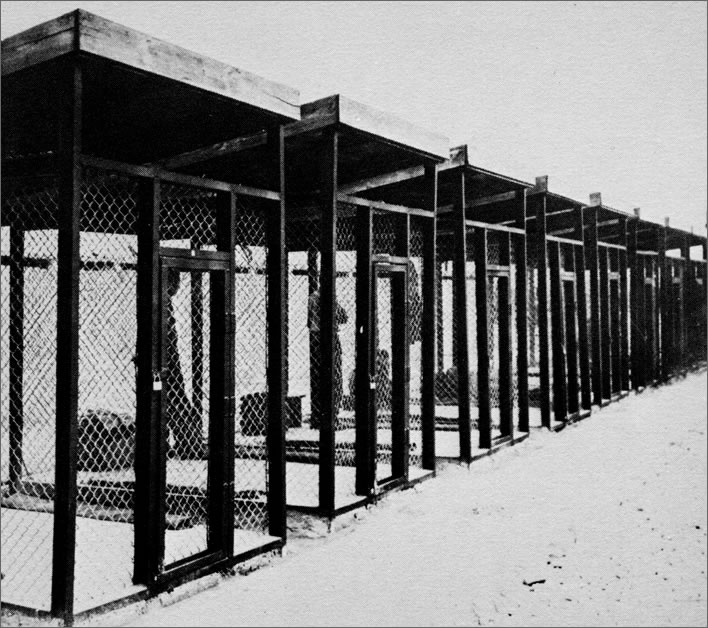

The cages at the United States Army Disciplinary Training Center in Pisa, Italy, where Pound was held for three weeks immediately following his arrest in May 1945.

The Americans sent him to an army prison camp, the 'Disciplinary Training Center' in Pisa, where he was kept in a reinforced cage under floodlights just in case his fascist friends tried to rescue him. After nearly a month of that he had a nervous breakdown, was given a psychiatric assessment and transferred to the more humane accommodation of a tent. He was given access to a typewriter in the medical centre of the camp and it was there that he started to write down the section of The Cantos called the Pisan Cantos. It is a regular observation on this blog that the mark of a true writer is that, however terrible the circumstances, they never stop scribbling. In this respect Pound was a true writer: there is some evidence that during his time in the cage he was even scribbling on sheets of toiletpaper.

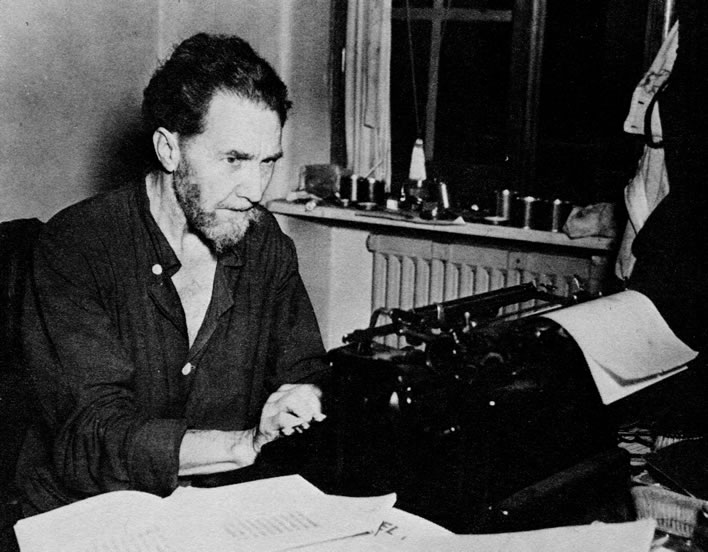

Ezra Pound writing the Pisan Cantos (presumably) on the typewriter in the Medical Center in the US Army Disciplinary Training Center in Pisa, 1945. Image: US Signal Corp.

After five months in the camp he was transferred to Washington and charged with treason. He avoided what could well have been life imprisonment by being declared insane – a declaration that was extremely easy to prove.

'When the men in the hats come around'. Two U.S. Marshals avoid fraternising with their prisoner after collecting him off a flight from Italy on 18 November 1945. Let's not speculate what he is saying to them.

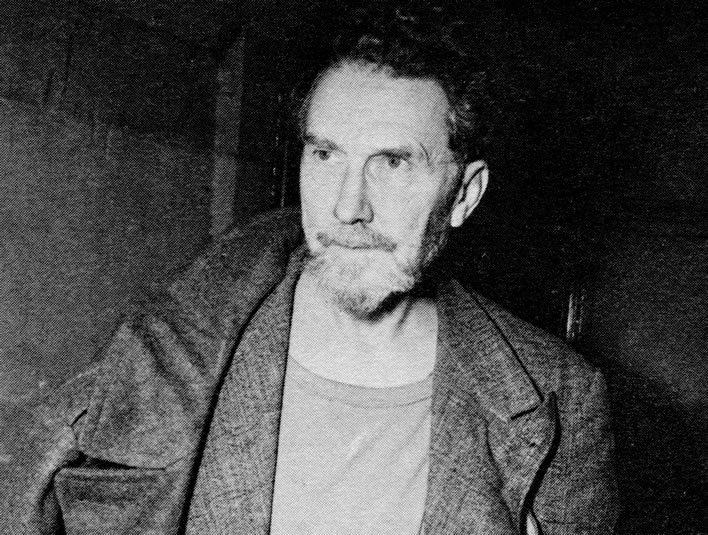

Ezra Pound following his arraignment in the District Court in Washington D.C. on 20 November 1945.

The details of Pound's time in the mental hospital, in which he was incarcerated for 13 years, are outside our scope, thank goodness, as is the discussion whether during this time Pound's mental door was rehung on its hinges (it wasn't). In 1958 he was released as incurably insane, gave a fascist salute and went home to Italy to face 14 years of familial turmoil, painful introspection, mental breakdown and senility.

That I lost my center

fighting the world

[C117:802]

He died on 1 November 1972.

Ezra Pound's body laid out in the Ospedale SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Venice on 1 November 1972. Olga Rudge is laying a bouquet of roses on the bed, which is decorated with a poet's laurels.

Ezra Pound's grave in the cemetary of Isola di San Michele in Venice. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 54, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate

Is his poetry worth examination?

The work done in the 40 years from 1925 to 1965, particularly The Cantos, is as unhinged as the personality of its creator – how could it be otherwise? But there are also some moments of outstanding, revolutionary poetry – great poetry, in fact.

nor shall diamond die in the avalanche

be it torn from its setting

[C74:430]

You, valued reader, now have to decide. Do you want to leave his crazed rantings and go and do something useful? In which case, leave this posting now – I really cannot blame you. Or shall we see if some diamonds can be rescued from the rubble of 40 years of the misguided intellectual effort of a sensitive master of the English language – who also happened to be unhinged?

Antennae of the age

Although clearly unhinged, Pound was indisputably a genius. I nearly wrote 'literary genius', but changed my mind because that would be too restrictive. I almost wrote 'flawed genius', but then which genius wasn't? He was a genius.

He lived through a febrile period of cultural innovation and, yes, derangement. All the '-isms' crossed his desk: the last years of Symbolism, then Futurism, Cubism, Imagism, Vorticism, the lunacy of Dada and so on. He experienced the deranged years before the First World War, then those four years when the so-called civilised world went collectively mad and slaughtered its young men, followed by a frantic quarter-century of boom, bust and desperation until the slaughter began again.

'Artists are the antennae of the race' he wrote in 1918, after the cataclysm of the Great War. It was an important insight for him, for he repeated the phrase several times over a period of decades. By 'antennae' he meant both radio antennae and insect antennae; both were sensors that respond to conditions that others cannot register.

The sensibilities of artists were like measuring instruments: barometers, wind-gauges, 'a nation’s writers are the voltometers and steam-gauges of that nation’s intellectual life'. [LE 58]

Artists and poets undoubtedly get excited and ‘overexcited’ about things long before the general public. [ABC 82f]

…

The concept of genius as akin to madness has been carefully fostered by the inferiority complex of the public. [ABC 82]

…

Before deciding whether a man is a fool or a good artist, it would be well to ask, not only: ‘is he excited unduly’, but: ‘does he see something we don’t?’ Is his curious behaviour due to his feeling an oncoming earthquake, or smelling a forest fire which we do not yet feel or smell? [ABC 82f]

…

Flaubert said of the War of 1870: ‘If they had read my 'Education Sentimentale', this sort of thing wouldn’t have happened.’ Artists are the antennae of the race, but the bullet-headed many will never learn to trust their great artists. If it is the business of the artist to make humanity aware of itself; here the thing was done, the pages of diagnosis. The multitude of wearisome fools will not learn their right hand from their left or seek out a meaning. [LE 297]

Pound's own antennae were overwhelmed throughout that period with all this newness: the race went mad and so did he. His radio-receiver intellect picked up only jumbled nonsense interspersed with whistles, crackles and bangs as European culture fractured and disintegrated.

Left-right: James Joyce, Ezra Pound, Ford Madox Ford and John Quinn. The famous photo of them in Pound's apartment in Paris (70bis Rue Notre Dame des Champs in the 6e arrondissement) taken in 1923. Pound and Ford were near neighbours. Ford and Quinn are perched on two of Pound's homemade chairs. Pound's rapiers are propped in the corner of the wall. Ezra and Dorothy left Paris for Rapallo in the autumn of 1923.

During these times he settled in places where he sensed a 'vortex', an innovative turmoil: London and Paris. These vortices were metropolitan, based on close and creative contact between artists of all types: writers, painters, sculptors, composers and so on. Pound earned some money as a music critic, wrote an opera, was a cultural journalist, a friend and supporter of artists such as Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891-1915), Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), James Joyce (1882-1941) and T. S. Eliot (1888-1965). His practical support for struggling artists of the time is very much to his credit.

But the vortices lost momentum and force, rotated more slowly, drew in less and less. In 1924 he moved to Rapallo in Italy, which some critics deem to have been a mistake, because in the little Italian town Pound just became isolated. There was no one at his side to moderate his innovation, no one of distinction and reputation to contradict him or argue with him, meaning that much of The Cantos is the record of the life of the mind of a solitary individual, thrown back on his own devices and left only with memories and with the garbled static from his antennae. Two decades later, in May 1945, after yet another cataclysm, he would emerge:

As a lone ant from a broken ant-hill

from the wreckage of Europe, ego scriptor.

[C76:458]

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!