Non-linear obscurity

Richard Law, UTC 2016-08-15 07:42

Backwards and forwards

The customer takes The Cantos off the shelf in the bookshop, feels its weight – 'Great bulk, huge mass, thesaurus' [C5:17] ('thesaurus' here also in the sense of 'treasure house' as well as 'word repository') – and observes its thickness, 802 pages.

It's a book. Or at least, it looks like a book: it has two covers, the pages are arranged in an immutable sequence and, to avoid all doubt, that sequence is numbered from 1 to 802. All the reader has to do is hold it the right way up, start reading at the correct end and keep going from left to right until there are no more pages. The conventions of book reading have been well established for about two thousand years and on the surface The Cantos seems to respect them.

The bookshop customer looks at the first page, which starts harmlessly enough:

And then went down to the ship,

Set keel to breakers, forth on the godly sea,…[C1:3]

then flips open some pages further on. The new passage is not quite so straightforward:

Io venni in luogo d'ogni luce muto;

The stench of wet coal, politicians…[C14:61]

take perhaps a bigger jump – it can't be all like that:

Take it before Prince Tçin gets there.

Thus Ouang Yeou to the Khitan of Apaoki

whose son was lost in the mulberry forest…[C55:293]

Yes it can. In fact, the more samples the baffled reader takes, the greater the bafflement. There are scraps of Greek, Latin, Italian, French, Provencale, Chinese ideograms, even the odd Egyptian hieroglyph; there are mysterious spacings and indentings of the text; there are many names, most of them unknown and a lot of quotations from unidentified works.

Wisely – and completely understandably – the book is returned to the shelf. To what purpose would all this reading effort be?

One source of difficulty for the unprepared reader is that although The Cantos looks like a book and has a strong beginning and a fractured conclusion, what goes on between those two points is only in the most general sense a linear progress.

At the deeper level it is a model of its times: frantic, deranged, imagistic. Pound's work, as Max Nänny memorably pointed out, was 'poetry for an electric age', non-linear. Pound himself had called his work a 'ragbag', jumbled up scraps of cloth that might one day make a useful patchwork. Nänny would later observe that The Cantos was really more a work of collage, that frantic medium that was so popular in the inter-war years, particularly with German artists in the middle of that Weimar frenzy. The casual reader loses all orientation in the turbulent jumble of ideas and allusions.

And worse: since some of these scraps or fragments embody in Pound's opinion a particular truth or fact they become labels for that truth, semaphore signals that are repeated, often separated by great distances of text. The reader is kept busy with the question: 'where did I come across that?'

That obscurity thing

But also in its finer grain The Cantos is infuriatingly obscure. The irritated reader may suspect at first that this is mere pretentiousness, which is how it probably started in my opinion, but further investigation suggests some kind of mental derangement.

We get the feeling that Pound writes as though he expects us to be able to see inside his head and to have read and experienced all the things that he has read and experienced. But the truth is exactly the opposite: he can have no reasonable expectation of such telepathic powers – unless, of course, he's mad. He needs the incomprehension of his readers to confirm the elevated status of his own understanding, which in itself also a kind of lunacy. I can't remember who it was or be bothered to look it up but someone once assigned a well-known character type to him: the 'village explainer'.

For example, Pound encountered Confucius in a French translation of The Four Books (my copy is dated 1858, so good luck getting yours). Consequently, when Pound is quoting the sage at us, those quotes are his transliterations from that French translation. He would later do his own translations and use other sources, making Confucius' work as inscrutable as its author. A substantial part of academic work on Pound is occupied with tracking down all these cryptic allusions from so many sources and in so many languages: a literary MRI of the contents of his head.

Academics who write about The Cantos have learned the essential skill of gliding over all the unknown or so far unexplained material. As we shall see in our own explorations in this piece the safest tactic is to quote only a line or two at a time; extend the scope beyond that and you risk including inexplicables that just have to be ignored.

We might also accuse Pound of possessing a repellent intellectual arrogance, but his mind had gone far beyond that into the deluded certitude that among moderns he alone had found the treasure and that the rest of us were mere ignorants.

This arrogance was deeply psychopathic. Two normal minds, one an expert on the presocratic philosophers and the other an expert on fluid dynamics, do not think less of each other because each knows next to nothing about the other's field. In contrast, when Ezra Pound towards the end of the 1930s discovers the work of Scotus Erigena, he gives us the impression that anyone who has not read Erigena's work is intellectually lacking – overlooking the fact that only a short while before he had not read Erigena's work either.

The roots of Pound's delusion that others could see inside his head seem to reach back to his London years. When we read the very early drafts of the first three cantos we find that they contain, aside from the usual impenetrables, the occasional explanatory remark that gives us some hints about his sources.

Pound paused after he had written those cantos and rethought the work. In a new approach he took his editorial hatchet to all that explanatory text: it was just explanatory material and not the condensed and hard core of his poem. If the reader cannot see inside his head, tant pis.

A draft of Eliot's Wasteland fell into his hands around the time of the early cantos: it was a much more comprehensible poem before Pound edited it. His changes increased its obscurity to such an extent that Eliot was embarrassingly forced to add notes, but those changes also increased its poetic value: Pound's interventions made it a better poem.

Pound's derangement was amplified by his desire always to 'make it new', a constant drive not merely to repeat or simply extend the culture that had gone before but to innovate – boldly going, if you like, where no man had gone before. Much of this innovation led to a dead end, but the innovation is interesting and worth a try. That said, however, no sane poet will follow The Cantos 802 page experiment, just as no sane novelist will follow James Joyce's 628 page experiment, Finnegans Wake.

That manifestations thing

If you are sceptical of the existence of all forms of spiritual manifestations then The Cantos is not for you. It is full of visionary moments, moments of enlightenment, of divine ecstasy. It is at heart a mystic work suffused with Neoplatonic ideas. In another context we touched on the power of ecstatic Neoplatonism to conjure up visions and views of the world that take us outside the quotidien, on to another plane. These may be just glimpses, moments of heightened awareness. The plane of another reality seems to intersect the plane of the everyday world.

Many artists – painters, writers or musicians – have left us witness of these moments. In the piece just referenced we looked at Plato, Aristotle, Van Gogh, Hölderlin, Hamsun, Hofmannsthal, but we could have equally discussed Blake, the chemically enhanced Coleridge, Wordsworth – apparently so grounded but in fact full of revelation – in fact so many of the writers and painters of the last two centuries. We mentioned in passing the Joycean epiphanies, the visions of Yeats and that sense of other reality, particularly across time. Even as recently as 2001 we find W.G. Sebald putting these words into the mouth of his character Jacques Austerlitz:

Once I dreamed that, after a long absence, I returned to the apartment in Prague. All the pieces of furniture were in the usual places. I knew that my parents would be returning from holiday soon and that I had to give them something important. I had no idea that they had been dead a long time; I thought only that they must be very old, around ninety or a hundred, which they would have been had they still been alive. However, when they finally stood in the doorway they were in their mid-thirties at most. The entered, walked through the rooms, handled this and that, sat for some time in the drawing room and talked together in the enigmatic language of the deaf and dumb. They took no notice of me. I suspect that they will soon depart for the place somewhere in the mountains where they now live. It seems to me that we do not understand the laws that govern the return of the past, but it seems to me more and more as if there were no time, rather just various spaces nested within each other in accordance with some higher stereometry, between which the living and the dead can transfer back and forth and the longer I think about it, the more it appears to me that we who are still alive are in the eyes of the dead unreal beings who only occasionally, under particular lighting and atmospheric conditions, become visible to them. As far back as I can remember, said Austerlitz, I have always felt as though I had no place in reality, as though I were not even there and this feeling has never been stronger than it was that evening in the Šporkova [apartment] when the eyes of the Rose Queen's Page [his child self in fancy dress in a photograph] bored through me.

[SEBALD:268f]

You may not be able to suspend disbelief in such writing; may not yourself be moved by altered states of consciousness that are not directly chemically induced; you may be sceptical of all visions and the susceptibility of some people to eidetic imagery. You may believe that Pound's visions and breakthroughs are merely the creative artifice of a poet struggling consciously for an effect. In which case, so be it.

Throughout The Cantos– from the very earliest ones in draft form to the very last flickers of the Poundian paradise – we are presented with visionary moments, moments when the divine breaks through into the everyday, or perhaps the tissue of the everyday is momentarily torn, allowing us to see beyond it.

These moments may be deliberately invoked, as, for example, right at the beginning of The Cantos in the translation of a section of Book 11 of the Odyssey, a passage in which Odysseus summons up the shades in Hell. But overwhelmingly they are involuntary manifestations – similar to those described in our previously noted piece on Hofmannsthal – in which Chandos tells us that he could not evoke his visionary moments of heightened perception consciously. For Pound, a pretty washerwoman on the back of an ass-cart can suddenly be a manifestation of the divine:

Beauty on an ass-cart

Sitting on five sacks of laundry

That wd. have been the road by Perugia

That leads out to San Piero. Eyes brown topaz,

Brookwater over brown sand,[C29:145]

'Topaz', an otherwise unusual word used six times in The Cantos, always in some divine context. Sixty-four cantos, 480 pages and an eventful quarter of a century later Pound has not forgotten that moment, nor has the attentive reader, we hope:

belleza (outside Perugia,

seated on three sacks of laundry,

[C93:626]

The very attentive reader will note that the five sacks are now three sacks, but will nevertheless be struck at the force this epiphanic moment must have had for Pound. It has lingered in the memory, from which come the major source of Pound's fragments.

Lights, shades and diafana

The particular trouble with Pound is that he just doesn't have epiphanies, visions or revelations in the way other artists do. Pound's visions, at least by the time they are presented to us, are irredeemably intellectualised and bedded in a nexus of knowledge from which the modern reader is completely estranged – or better: from which every reader is estranged. Pound doesn't just see visions, he sees characters from the Divine Comedy.

Pound's early literary obsessions were with troubadour poetry (c. 1100-1350) and the works of Dante Alighieri (1265?-1321). In other words, his first field of interest was a late medieval one. In this he was not in any way modern for his times, if anything, slightly out of date, since the interest in those times had already been and was almost gone. The boom in those two subjects had come at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries and was already fading when Pound arrived in London in 1908. But there were still plenty of works on the troubadours and Dante in the publisher's catalogues: the young Pound was not a Modernist or revolutionary poet, but a rather fusty traditionalist.

He threw himself into the work of troubadours such as Arnaut Daniel (fl. 1180–1200) and Bernart de Ventadorn (1130?-1200?), Dante and the Italian poet and troubadour Guido Cavalcanti (1250?-1300), Dante's friend. Pound read eclectically in the works of that period, also in the work of medieval philosophers.

To the Neoplatonism he acquired from his Renaissance studies he added ideas picked up in his wanderings through medieval philosophers, particularly (in chronological sequence) Johannes Scotus Erigena (815?-877?), Richard of Saint Victor (?-1173) and Robert Grosseteste (1175?-1253).

It is fair to say and in no way a criticism that the educated modern non-Poundian, non-specialist reader has no idea who these people are or what ideas they represent. This statement is probably also true of Pound's contemporaries. To be brutally frank these writers have nothing – repeat: nothing – to say that can be of the slightest relevance to anyone living after the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. We study them as historical artefacts in the context of their times, not as people who said anything that a modern person requires to know.

Pound journeyed through this intellectual landscape in his characteristically pick-n-mix way: ideas about light and colour from Grosseteste are tossed in with gleanings from Erigena and with obscure poems from Cavalcanti and the troubadours. Add to the resulting collection of Neoplatonic, Neopythagorean shadows and lights the Dantescan spirits of darkness and light and Odyssean shades and we have the perfect Poundian storm.

Pound's essay on Cavalcanti, published in 1934 but written sometime after 1925, spews forth a jumble of half-digested pieces, 'creatively' translated from all these sources and many more. One of these lumps is the concept of the diaphan, one of the central ideas we have to cope with in The Cantos. The word is used by the troubadour Arnaut Daniel and the philosopher Grosseteste. In Grosseteste's works on light and colour the Latin word diaphani is the term for transparent media. Pound, the magpie searching for sparkling things, alights on plura diaphana as 'multiple media', but ignores the word that follows it, diversorum.

This passage, which Pound takes to be a treatise on the manifestation of spirits (?) by light acting on otherwise transparent planes of being (?) in the original [GROSS De Luce / De Iride] is actually a sober, nearly-scientific discussion of the propagation, reflection and refraction of light. There is simply no mystery here, which is why some modern commentators on Grosseteste see him as one of the first scientists. The careful reader of Grosseteste is completely baffled by Pound's interpretation of the philospher's work.

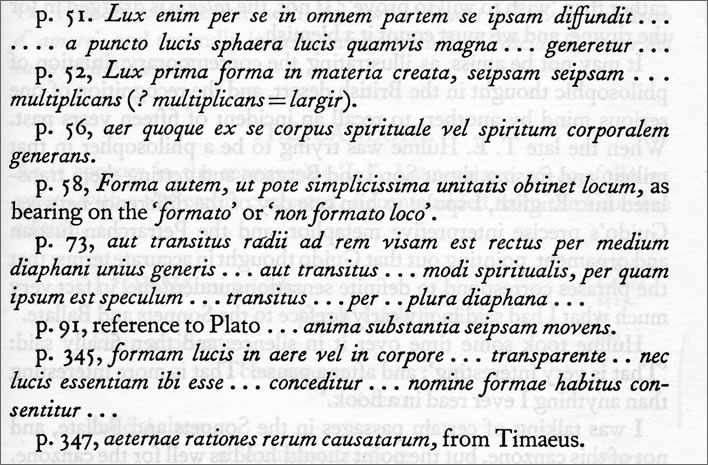

In his Cavalcanti essay, Pound's technique for quotation from Grosseteste is a telegram-style picking out of those words and phrases which, freed from boring bits such as context and grammar, could possibly be interpreted in a mystical way.

Telegram-style scholastic philosophy from Ezra Pound's essay, 'Cavalcanti' [LE:161]. After reading Pound's telegram we might come to the conclusion that the sober-sided proto-scientist Grosseteste could just as well be a teacher at Hogwart's School.

Does Pound believe that there are multiple transparent layers of reality (diaphani, diafana) that under certain conditions become visible to us (similar to the situation described by Sebald)? Or perhaps the visibility of one layer disappears to reveal the layer underneath it? I have no idea what exactly is inside Pound's head in this matter – we have to leave it in a simple formulation: in The Cantos, things appear and disappear.

Hints to the wise

In The Cantos these involuntary breakthroughs are often prefigured by hints of what is to come. These hints usually take the form of a word or a phrase alluding to another plane of reality. This is yet another reason why The Cantos is such a difficult read for the uninitiated: the resolution of these hints may come a long way away in the poem. The wide scale of these allusions across many pages and many cantos is the proof that The Cantos is not really a ragbag, but that it really has some sort of 'major form', as the professionals put it, at least in the thematic sense.

It is not an accident that one of the principal themes of the very first cantos was the Metamorphoses of Ovid. The world of the everyday can at any moment transform into things 'rich and strange'.

Often, as we shall see, we tremble in a preliminary state that prefigures the moment itself. The breakthrough is sensed, but the actual moment of breakthrough may come many lines later or may have come many lines before and is now just being recalled to memory as a dying echo, or a shorthand reference to the longer description. These hints, which are often just a single word or short phrase, may puzzle and annoy the reader, but they are important tokens – almost statements of musical themes that will be developed as the poem progresses.

Fragments, bits and pieces

Let's illustrate this with a characteristic passage that will have the unguided reader tearing out lumps of hair in frustration – although by the time the reader has arrived at Canto 93 there will be hardly any hair left to tear out. In fact, this is one of the more immediately accessible passages. It is not offensively obscure – it reads quite well even if you have no idea of what it is about. Just don't ask.

'Oh you, as Dante says

'in the dinghy astern there'

There must be incognita

and in sea-caves

un lume pien’ di spiriti

and of memories,

Shall two know the same in their knowing?

[C93:631]

In the opening two lines of this passage Pound warns us – albeit somewhat late in the day – that our progress through The Cantos will not be an easy passage:

'Oh you, as Dante says

'in the dinghy astern there'

Ezra being Ezra, he does this by invoking some words of Dante from one of the models for The Cantos, the Divine Comedy. This allusion comes from the moment at the opening of Canto 2 of the Paradiso where Dante is sailing from the Garden of Eden to Paradise. He warns the reader following him in his 'dinghy' – Dante's term was piccioletta barca, 'little boat' – to turn back now:

O you that follow in light cockle-shells,

For the song’s sake, my ship that sails before,

Carving her course and singing as she sails,

Turn back and seek the safety of the shore;

[PAR:2:1-4]

We, his battered readers trailing behind him in our little boats, have long ago been warned that The Cantos are ‘By no means an orderly Dantescan rising’ [C74:443]. On the contrary, we can expect a very disorderly Poundian ascent to Paradise and we poor readers are in for rough waters.

In the next lines we have to cope with a characteristically Poundian jumble of fragmentary allusions, which he opens with

There must be incognita

‘incognita’ in its major sense is 'unknowns' (Latin incognita, the neutral plural of incognitus, 'unknown'). We might read this as ‘unknowables’ in the sense of hermetic knowledge, the 'mysteries'. And, of course, with Ezra there is frequently a woman hidden away somewhere in the text, so, at a bit of a stretch, we might take incognita to be an Italian word, the feminine of incognito, 'unknown [female]', the female goddess who does not care to reveal her true identity and who passes amongst us disguised and usually unrecognized except for that moment of manifestation – perhaps as a 'beauty on an ass-cart'. There are many such moments in The Cantos in which the disguised female goddess of classical tradition is perceived for what she is: ‘a great goddess, Aeneas knew her forthwith’ [C74:435], a quotation we have used elsewhere.

That's Ezra for you, always these mysteries! And now some more:

and in sea-caves

un lume pien’ di spiriti

The mention of 'sea-caves' takes us back to a fragment a mere 16 lines previous – nothing of a separation in Poundian terms – where we were told

Such light is in sea-caves

e la bella Ciprigna

Where copper throws back the flame

[C93:631]

La bella Ciprigna is 'the beautiful Cyprian', the term used by Dante in Paradiso, Canto 8, line 2, to denote Aphrodite/Venus, sea-born and sea-borne, associated through her island of Cyprus with copper, cupris ('Cu'). We shall leave the copper which 'throws back the flame' without further comment, otherwise we shall have to jump to the end of Canto I, make a tour through the Homeric Hymn VI, and then… well, you get the idea. On the same principle we shall also leave unexplored 'sea-caves', a term which occurs several times in The Cantos.

Returning to our original text – how often we shall have to write that! – Pound now tells us that we shall also meet ‘un lume pien’ di spiriti,’ the light of the spirits of love that emanate from the eyes of the beloved as described by Dante's friend, Guido Cavalcanti (1250?-1300) in Le Rime, poem 26. The relevant lines in Pound's own translation of this poem, 'Ballata V', make everything much clearer:

Light do I see within my Lady's eyes

And loving spirits in its plenisphere[TR:107, 'Cavalcanti Poems']

Clear? Quite. On to the next lines – no time to linger:

and of memories,

Shall two know the same in their knowing?

We would also be wise not to follow the tangled web that Pound weaves in The Cantos around memory, represented by the Greek goddess Mnemosyne, who was the mother of the nine Muses. We would find ourselves in a prose piece of W.B. Yeats quoting a charming poem by the 19th century writer Walter Savage Landor. No! Stop! There must be limits, just as there must be incognita.

Epistemology made easy

and of memories,

Shall two know the same in their knowing?

In the eight words of the second line Pound confronts us with the core epistemological fact that actually sabotages The Cantos, our inability to see inside the heads of others, to share or understand those memories that are stored there, to comprehend their thoughts.

It is a magnificent summary of the essence of epistomology, ‘Shall two know the same in their knowing?’. It is much deeper that T. S. Eliot's trite invocation of the idea of an 'objective correlative' that was supposed to be capable of reliably summoning up emotion in different people. Pound questions the whole idea that people can know each others minds.

For example, when I call something 'blue' and you call something 'blue' the philosopher is left wondering how we can say that our experience of 'blue' is the same. We share a word but we cannot share the experience, in the same way that the 'normally' sighted person cannot directly share the world of the colour-blind person and vice versa. Objects and words become loaded with personal significance which others can imagine but not experience directly: the flowers left on a grave are not the flowers the florist or the gardener sees. Language is just a workaround that we use to surmount this problem of shared experience in everyday life.

The exasperated reader of The Cantos, who so often has cried out ‘How am I supposed to know what this man is on about? How can I be expected to see into his head?’ now has the answer: in the end, he or she cannot know. What then is the point of writing? I don't know, you tell me. And reading? Ditto.

The question of the nature of human communication, the question as to whether the reader of even the most ‘self-explanatory’ work can ever fully grasp its nature as seen by its creator, the whole problem of literary obscurity is here brought to a point.

Exegesis may sometimes be able to tell us who the remembered were, may elucidate places and times and incidents, may derive the sources of allusions and their relevance, but the source memory remains unreachable.

We practise a questionable habit with every work of art – whether text, image or music – we delve into the artist's biography and try to 'explain' the work in terms of that. And what do we do with all these incomprehensible fragments of Pound's memory whilst we are waiting for the hoped-for elucidation?

Even when we find a source for a phrase or quotation, more often than not we find ourselves repeating the words Pound ascribes to Professor Lévy in Canto 20 'Now what the DEFFIL can that mean!' [C20:90]. So, for example, we cheer at a sentence in a late-published 'Addendum' for Canto 100 which reads:

'A pity that poets have used symbol and metaphor

and no man learned anything from them

for their speaking in figures.'[C100:799]

Pound has put this text in quotation marks, so we must assume that these are not Pound's words but those of someone else. As far as I know, no one knows the source of this quote. Even if we did it is unlikely to help us elucidate the meaning.

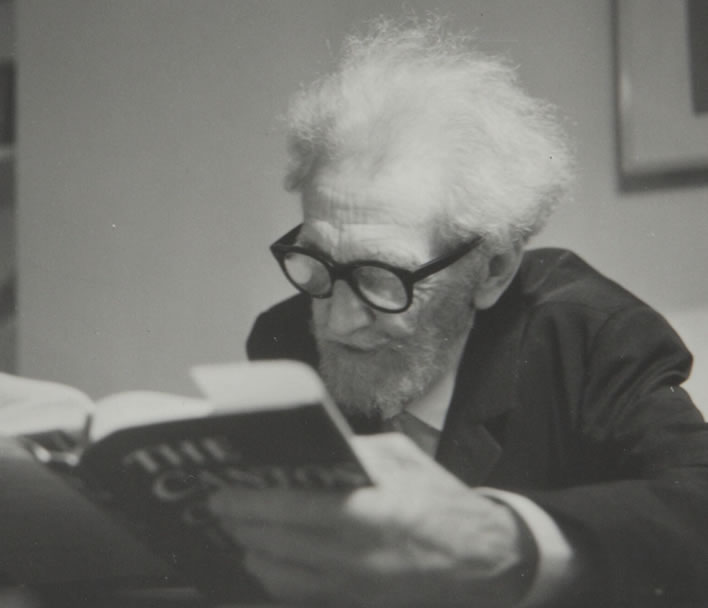

Ezra Pound reading The Cantos: 'Now what the DEFFIL can that mean!' [C20:90]Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 241, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

Taken at face value it is a criticism of almost every poetic text that Pound ever wrote. Can it possibly be that Pound is quoting this statement approvingly? Or is it meant satirically, or critically, or self-critically? Questions upon questions. It seems unlikely that we will ever know and therefore it remains just another one of those inaccessible bits of knowledge that became totally and permanently inaccessible on 1 November 1972, one of those bits from which 'no man [has] learned anything'.

Picking over the pieces

Our browsing customer in the bookshop closed The Cantos, put it back on the shelf and left the shop with the impression that Pound's book is irredeemably obscure and thus not worth the effort of elucidation. This impression is understandable, also to a great extent true.

Perhaps it is worth some effort, though. Can anything be recovered? Let's try taking this non-serial work of the electric age and look as it as a collage of overlapping pieces, pieces from many sources, some obvious, some obscure or unidentifiable. In doing this we don't feel the need to explain every little scrap we come across. We can also take some scraps and leave others untouched. We are, after all, cool moderns, even post-moderns or maybe even post-post-moderns. At moments of uncertainty we can just use that popular modern expression: 'it is what it is'.

Out of Pound's collage we are going to pick what we will call the 'shipwreck theme', which, after Pound's personal shipwreck at the end of the war, became one of the great themes of the later work. We, following him in our picchiolette barche, are going to have to hold on tight.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!