Conclusion and bibliography

Richard Law, UTC 2016-08-15 07:47

Conclusion

At the start of this post we asked a question: why should we bother with Ezra Pound and his monstrous poem? The answer is: we shouldn't. The Cantos is a failure and a dead-end. The only possible activity with this work is autopsy by specialists – slap the cadaver down on the table, open it up and see what went wrong. Not my idea of fun, but there are doctorates to be had in this morgue.

Pound got it into his head to write a 'long poem' that would be the 'tale of the tribe'. What is a 'long poem'? Eliot's Four Quartets comes in at around 30 pages; Browning's Sordello, the great unread and unreadable that Pound so admired, stretches to about 200; the blind Milton dictated Paradise Lost in five years and took around 500 pages; my copy of La Divina Commedia extends to 900 pages with extensive commentary taking up about a half of each page – let's say 500 pages of poetry. The Cantos staggers to a stop after 25 years and 800 pages.

Its vast length aside, Ezra Pound's 'long poem' was doomed to failure as soon as he took The Divine Comedy as his principal model.

That Dante thing

No one has ever written a second Divine Comedy– not even nearly. There is a reason for that, which is that the work was a dead end. Even in its own time it was obscure: one of the first efforts of Italian scholars was to write commentaries for the work. The annotations to the Commedia are relatively straightforward: a personage described here, a philosophical or theological nicety discussed there. Even so, the commentaries and annotations to the work take up nearly as much space as the poem itself – probably more if you allow for their tiny typeface and abbreviated style.

Dante's moral certainties and ethical classification could not be repeated nowadays. Dante was writing in a biography-free time and could do with his figures what he pleased. We find, for example, that Dante places the great Habsburg emperor Rudolph I in 'Ante-Purgatory' [PUR:7:91f], where he lolls around in negligent idleness, having failed to pay enough attention to the problems of Italy. This is the emperor who rode his backside off for 20 years restoring the Holy Roman Empire from the chaos into which it had fallen, a dynamic, prudent and exceptionally pious ruler right into great old-age. Our astonishment increases when Dante reports that Rudolph's shade is being comforted by that of King Ottokar, Rudolph's most bitter opponent, whom Rudolf dispatched to his current position in Purgatory at the Battle of Marchfeld in 1278.

In contrast, choose a modern ruler according to your taste, consider how much biographical information we have about him or her for the evaluation, then assign them to a single position in Dante's scheme. You cannot do it. Unfortunately for Ezra, most people these days would not make Mussolini one of the great figures of the time, send Jews and Churchill to the lower regions of Hell and put a troubadour's girlfriend in Heaven. If only for that reason alone, Pound's Cantos has lost any chance of greatness.

Mixing it up

Pound took the journey/descent-ascent metaphor from the Divine Comedy and made its usability a thousand times worse. Whereas each of Dante's cantos is founded on some clear category with almost always only single instances of allusions within it, Pound's categories and his allusions are usually totally fragmented.

The task of the annotator of the Divine Comedy is relatively straightforward drudgery; the task of the Pound commentator is impossible – almost impossible? – no: impossible. We have ourselves seen the way the 'shipwreck theme' is spread out across about 350 pages: single words, phrases and here and there or a few lines stirred in amongst so many other Poundian scraps. The reader has noted with irritation how much effort we have had to expend explaining juxtaposed lines that just happen to be woven in among our theme and which may or may not relate to it in some way in Pound's mind.

Only by exercising strict cerebral hygiene have we avoided foundering hopelessly with every new line. We have fortunately been spared having to deal with the tedious, monomanic groups of cantos which follow a single theme in numbing and incomprehensible detail: Adams, Leopold, Chinese history.

A saner poet might have written the shipwreck theme within the scope of one canto, perhaps adding some interesting background. Such a canto would have made a fine transition from the Pisan Cantos to Rock-Drill. It would have been a legitimate demand to make of the reader that this canto was based on Book V of the Odyssey. Instead, Pound fractures the theme almost beyond comprehension across time and space and thus wrecks any chance of his readers disentangling it.

Unlike the Dante drudge, the Pound commentator has an impossible task trying to make all these tangled threads intelligible to the non-specialist reader. No one will write another Divine Comedy, no one will write another Cantos. It is a failure that will never be repeated – although Pound's work encouraged a number of younger poets to write incomprehensibly, too. Oblivion has been their just reward. Is it fair to say that if Pound had not been imprisoned after the war oblivion would have been his reward, too? The backstory has taken over.

The question of merely quoting phrases or even just odd words from obscure works is another problem. The quotation does not inspire or inform the poem, the reason for the quotation is usually just as obscure as its source. James Joyce, a much more thoroughly educated and intelligent writer than Pound, was able to write his masterpiece Ulysses alluding to the form of the Odyssey, but in such a way that it can be read and enjoyed by someone unfamiliar with its prototype.

A deservedly famous image of the moment Ezra Pound meets up with the shade of James Joyce (1882-1941) in Fluntern Cemetery, Zurich in 1967. Joyce died in Zurich in 1941 of a perforated ulcer, his wife Nora died in 1951 and was buried by his side (with later their son, Giorgio in 1976). The statue is inspired by the 'gracehopper' from Finnegans Wake and is by the American sculptor Milton Hebald. There have always been some flowers in the open book on the few occasions I have been there. Image: ©Horst Tappe-Stiftung.

Rescue party required

Is there anything good in The Cantos?

Yes, but the frustrating thing is that these fragments of verse that glow with poetic skill and intelligence are buried under an avalanche of the incomprehensible. Ezra may have been unhinged and his Cantos a general shambles, but there are moments when he shows us clearly what a master of the English language he was, certainly the greatest in the 20th century and one of the greatest overall. That being the tragedy of The Cantos, that the greatest lyric artist of his time ground himself into the dust with his ill-conceived 'long poem'. Here are just a few examples of the sort of thing Pound was capable of.

The first requires no annotation at all and is thus immediately accessible – it is just a wonderful piece of observation:

The water-bug's mittens

petal the rock beneath,

The natrix glides sapphire into the rock-pool

[C91:616]

In the next example the reader probably needs to know that Pound is describing his visit to the Roman remains at Saint-Bertrand-De-Comminges in Provence in 1919. Apart from that, everything is clear.

From Val Cabrere, were two miles of roofs to San Bertrand

so that a cat need not set foot in the road

where now is an inn, and bare rafters,

where they scratch six feet deep to reach pavement

where now is wheat field, and a milestone

an altar to Terminus, with arms crossed

back of the stone

Where sun cuts light against evening,

where light shaves grass into emerald

[C48:243] (my indentation)

The final example is Pound's magnificent rendering of Odyssey Book 10, ll. 490-5. Here is Fitzgerald's translation:

That day, and all day long, from dawn to sundown,

we feasted on roast meat and ruddy wine,

and after sunset when the dusk came on

my men slept in the shadowy hall, but I

went through the dark to Kirkê's flawless bed

and took the goddess’ knees in supplication,

urging, as she bent to hear: 'O Kirkê,

now you must keep your promise; it is time.

Help me make sail for home. Day after day

my longing quickens, and my company

give me no peace, but wear my heart away

pleading when you are not at hand to hear.'

The loveliest of goddesses replied:

'Son of Laertes and the gods of old,

Odysseus, master mariner and soldier,

you shall not stay here longer against your will;

but home you may not go

unless you take a strange way round and come

to the cold homes of Death and pale Perséphonê.

You shall hear prophecy from the rapt shade

of blind Teirêsias of Thebes, forever

charged with reason even among the dead;

to him alone, of all the flitting ghosts,

Perséphonê has given a mind undarkened.'

Now Pound's masterful adaptation of the bedroom whispers (my quotation marks for Kirkê's words):

'Who even dead, yet hath his mind entire!'

This sound came in the dark

'First must thou go the road

to hell

And to the bower of Ceres' daughter Proserpine,

Through overhanging dark, to see Tiresias,

Eyeless that was, a shade, that is in hell

So full of knowing that the beefy men know less than he,

Ere thou come to thy road's end

Knowledge the shade of a shade,

Yet must thou sail after knowledge

Knowing less than drugged beasts'

[C47:236]

In these examples the poetry stands on its own or needs only the merest background hint. I can think of Betjemen poems that are more obscure. Extracting deeper insights such as the Platonic nuances of the water-bug's mittens can be left to the reader – that kind of thing is after all what readers do. Perhaps there is scope for an anthology, The Readable Ezra Pound, containing just the good bits.

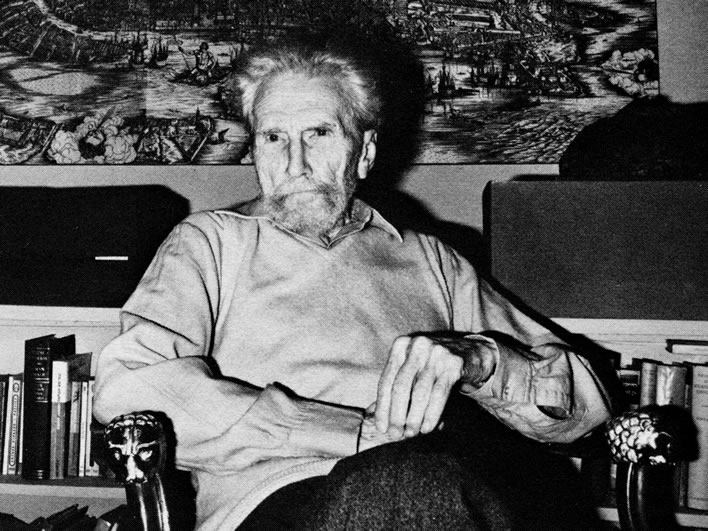

Ezra Pound in his study in Venice in 1971. Pound's habit of scratching the back of the hand was remarked on by several visitors during this time. Image: ©Horst Tappe-Stiftung.

Coda

In 1963 a 16 year-old found himself in a small bookshop in a small town in Yorkshire in northern England. In a rotating bookstand he came across Guide to Kulchur (Faber, 1938) by Ezra Pound. A hardback, it would make a large impact on his pocket money, but even to casual browsing it looked like no book he had ever read and was not to be resisted.

Whilst he was fishing out his money his attention was drawn by the young man running the bookshop to a poster advertising a lecture on the Indian polymath, poet and mystic Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941, a death which happens to have been 75 years ago on 07.08.2016). Tagore, among his many other achievements, figured in the vortex of Pound's London years, something the assistant clearly knew.

In this small bookshop in a small town in the Yorkshire dales an arm of the great spiral vortex that Pound had sensed in London in the first two decades of the 20th century could still be felt simultaneously by two strangers – a kind of gravity wave left over from that tumultuous time long ago that is still detectable with the right antennae.

It took the youngster many years to break away from the crazed influence of that remarkable book and its remarkable author, though not before it had done him rather a lot of damage. There comes a time though to discard the spar, seize the veil and set off paddling towards the distant shore.

Images

The majority of the illustrations of Ezra Pound used in this piece come from the excellent collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Where images are not already in the public domain their use in this posting falls under the rubric of 'fair use': not-for-profit, non-commercial, low-resolution reproduction for the purpose of discussion and academic comment. Readers should be aware that downloading the images and using them in other contexts may get them into trouble.

After so much heavyweight text let's lighten up and cast a glance at at some of Ezra's memories, some interesting photographs:

Left: Ezra Pound (nearly 5) on 25 July 1890. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 43, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate. Middle: Ezra Pound (? I am not convinced that this is him) (19) in 1904. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 54, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate. Ezra was a relatively frequent visitor to Europe during his youth. Right: Ezra Pound (24) in 1909. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 43, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

Chick magnet Ezra Pound (15?) lurking in the bushes in 1900(?) in the uniform of the Cheltenham Military Academy in Cheltenham Township, Pennsylvania. Possibly treading the boards in some theatre production – one of the girls is dressed in her finery, the other much more simply. This photograph must have been taken towards the end of his time at the Academy because his uniform has 'officer' stripes on the sleeves. Image: Beinecke Library YCAL MSS 43, Yale; ©Olga Rudge Estate.

Bibliography

Books and other sources referenced in this post.

| Ezra Pound | |

| ABC:page | ABC of Reading. London: Faber and Faber, 1979. |

| C canto:page | The Cantos of Ezra Pound. 4th collected ed. London: Faber and Faber, 1987. |

| CEP:page | Pound, Ezra and King, Michael. Collected Early Poems of Ezra Pound. London: Faber, 1977. |

| CSP:page | Collected Shorter Poems. London: Faber and Faber, 1968. |

| GK:page | Guide to Kulchur. London: Faber and Faber, 1938. |

| LE:page | Literary Essays of Ezra Pound. London: Faber and Faber, 1960. |

| TR:page | The Translations of Ezra Pound. London: Faber and Faber, 1970. |

| Homer | |

| IL:chap:line | GREEK and ENGLISH online: Perseus. |

| OD:chap:line | ENGLISH: Homer, and Robert Fitzgerald. The Odyssey. New York: Doubleday, 1963. The standard text used in this post. GREEK and ENGLISH online: Perseus. |

| Dante | |

| INF:book:canto:line PUR:book:canto:line PAR:book:canto:line |

Dante, Divine Comedy online, according to taste: Princeton Dante Project / Dartmouth Dante Project / Dartmouth Dante Project Reader. |

| Other | |

| GROSS | Grosseteste, Robert, De Luce, also De iride is accessible here. The site is useful but apparently no longer maintained. |

| PHIL:book:chap:page | Philostratus the Athenian, Vita Apollonii, Carl Ludwig Kayser, Ed. |

| PROP:poem:lines | Sextus Propertius, Elegies, Lucian Mueller, Ed. (Latin) Perseus. |

| SEBALD:page | Sebald, Winfried G. Austerlitz. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verl, 2013. |

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!