The Tyrolean Fatherland

Richard Law, UTC 2017-04-24 16:42

Michael Senn's busy political life in those turbulent times is well documented but outside our scope. Nevertheless some background about the political turmoil of the time is necessary – we'll meet a number of Tyroleans in the biography of Senn, the Tyrolean patriot. An executive summary may be helpful for non-specialists.

However, the history of this period in the Tyrol is extremely complex – for almost every viewpoint there is a counter-viewpoint – and is still an active field for research. Do not take anything in this summary as the last word on the subject. For those who wish to know more and who read German a reliable and compact review can be found in [Kern].

At the time of Michael Senn's birth the Tyrol was a state of Austria with borders to Italy, Switzerland and Bavaria. Before mass tourism it was a poor region, mainly reliant on hill-farming.

Top: Franz von Defregger (1835-1921), Bäuerin am Spinnrocken / Farmer's Wife at the Spinning Wheel, 1873. Defregger built a good career on genre paintings of life in the Tyrol. A large collection is available online at zeno.org. Amidst the grinding poverty here we can also see the large house number, one of the administrative innovations of the Empire of Paperwork in the 1770s.

Bottom: Franz von Defregger, Landecker Häuser / Houses in Landeck, 1870. More poverty, this time a scene in Landeck, the area from which Barbara Zoller, Johann Senn's mother came. It was also the home town of Aloys Fischer, who will play a large role in Johann Senn's biography. Time moves slowly in mountain communities – we can assume that the scene a century before, during Barbara's time, would not be much different.

Poor regions export their superfluous children, as we know today, and many Tyroleans were driven to seek a living outside its borders: in the 18th century the word 'Tyrolean' was associated with men who travelled widely hawking patent medicines, blankets, gloves and so on. The women sold needles, ribbons and often themselves: the word Tirolerin came to be used as another term for prostitute. In the minds of the other residents of Europe the Tyroleans were often decorative oddities, almost in a state of nature: the men in their leather shorts and broad-brimmed hats and the women in the Dirndlkleid.

Three genre scenes from Franz von Defregger, illustrating Tyrolean sartorial exceptionalism.

Top: Wilderer in der Sennhütte / Poachers in the mountain cottage, 1876. Wilderer, poacher, not Jäger, hunter, as we see from the expression on the mother's face.

Middle: Auf der Alm / At the mountain meadow cottage, 1881. The girl is churning butter, the hunter's dog is taking advantage of the distraction. During summer, when the animals are grazing on the high pasture, butter and cheese are produced on the spot in the Almhütte, a cottage dairy.

Bottom: Der Salontiroler / The salon Tyrolean, 1882. The 'genuine' Tyroleans mocking the natty, affected Tyrolean. During the 18th century many of the courts of Europe affected to have a Tyrolean among their menagerie.

Not only their appearance was odd. The inhabitants of the Tyrol were fanatically Catholic, fanatically loyal to their emperor and – paradoxically – fanatically independent. Their motto was 'For God, Emperor and Fatherland', 'Fatherland' meaning here 'Tyrol'.

Top: Albin Egger-Lienz (1868-1926), Die Prozession / The Procession, 1903. Egger-Lienz was a Tyrolean painter.

Bottom: Albin Egger-Lienz, Feldsegen / Blessing the fields, 1896.

That independence and exceptionalism meant that, unlike the rest of the male population of the Habsburg Empire, the men of Tyrol were not required to do military service: they had their own militia troops – rather like the Swiss – and would muster to defend their interests when required. Leave them to themselves and they would be pious, loyal and reliable subjects.

Poking the wasps' nest

The calm of this laissez-faire relationship did not survive its encounter with the great meddler, the Emperor Joseph II (1741-1790, reigned alone 1780-1790). Joseph, with his 'enlightened' mind and hasty, intemperate nature, took exception to Tyrolean exceptionalism and the simple, colourful, bigoted, icon-laden and superstitious Catholicism of these mountain folk. Joseph wanted to turn the Holy Roman Empire into an orderly 'enlightened' state that was administratively homogeneous, not an empire of oddities such as the Tyrol.

As the decrees fluttered from his hasty, despotic pen the inhabitants of the Tyrol – and most of the other parts of the empire, for that matter – became increasingly enraged. The hasty retractions, clarifications and adjustments also fluttered, but by the time the Lord took mercy on the Austrian Empire in 1790 by finally calling Joseph to his bosom, much damage had been done. His successor, Leopold II (1747-1792), managed to pull back the empire from the cliff's edge where Joseph had left it tottering, but the next challenge was just round the corner: Napoléon Bonaparte.

Leopold had only a two-year reign. He was succeeded by his son Franz II/I (1768-1835) in 1792, when the French wars were just starting. In 1796 the French attacked Tyrol, which, from Napoleon's European perspective, was a key transit region. The French were quickly driven out by the Tyrolean army.

Tyrol, the pawn on the Napoleonic chessboard

The next great setback for the Tyrol occurred outside their territory: the great victory of Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805. Tyrol was no longer a proud, independent statelet, it was just a pawn in the negotiations of the Treaty of Pressburg, 26 December 1805, which rearranged the chessboard of Europe. Tyrol, a useful pawn, was handed over to Bavaria.

Franz II/I had already in 1804 accepted the reality of the collapse of the rickety structure that had been the Holy Roman Empire. He called what was left of it the 'Austrian Empire' and declared himself to be emperor of that, styling himself Franz I, the first Franz of the new empire. After Austerlitz the old Holy Roman Empire was effectively no more, so in 1806, the emperor with two crowns, Franz I and Franz II, laid down the crown of the Holy Roman Empire and became simply Franz I, Emperor of Austria. Emperors are really not like us. In our text from now on we shall usually call him Franz II/I.

The Bavarians were Josephinian in their 'enlightened despotism', which meant trouble for their new underlings, the highly unenlightened Tyroleans. True to their mentor, the Bavarians immediately started hasty actions to integrate their new territory into Bavaria. Many 'superstitious' religious practices were circumscribed, the number of feast days was reduced, taxes were raised and – worst of all – the old freedom from external conscription was removed. The Bavarians pursued forcible conscription harshly throughout the Tyrol.

Betrayals

It was in the time after 1805 that Michael Senn was most active. He attempted to coordinate resistance to the Bavarians, but all to no avail. An uprising against the Tyrol's new masters began in Innsbruck on 9 April 1809, under the leadership of an even more charismatic figure, Andreas Hofer. Senn played his part, but the French got involved and after some heroic battles the game was up.

Franz von Defregger, scenes of the Tyrolean uprising.

1: Andreas Hofer: left, painted 1880; right, 1901.

2: Der Kriegsrat Andreas Hofers / Andreas Hofer's war cabinet, 1897. Battling the French and the Bavarians.

3: Treffen zum Aufstand / Mustering for the uprising, 1900.

4: Heimkehrender Tiroler Landsturm im Kriege von 1809 / Return of the Tyrolean infantry in the war of 1809, 1876. Tyrolean militia returning after one of their early victories in the 1809 conflict with their French captives in tow.

5: Das letzte Aufgebot / The last call-up, 1872.

At the end of May 1809 Franz I proclaimed that there would be no Austria without the Tyrol – conveniently forgetting that he had handed it over to the Bavarians barely three years before and also conveniently overlooking the fact that Vienna was in the hands of the French and that at that precise moment he and his government were sitting in Hungary, watching events at a safe distance. It was a promise he was always powerless to keep.

Another distant battle, another chess move on the European board, this time the Battle of Znaim in Moravia between the French and the Austrians on 12 July 1809. Despite Austrian numerical superiority on the battlefield, Franz's younger brother, Archduke Karl, on his own authority concluded a ceasefire with Napoleon. A clause in the agreement explicitly required the occupation and pacification of the Tyrol, still a pawn on the European chessboard.

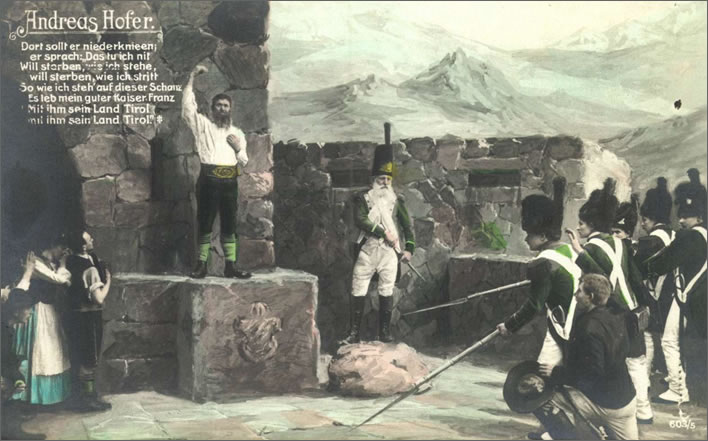

The execution of Andreas Hofer 20.02.1810, visualised on a postcard of 1899. Image: B. Johannes, k. u. k. Hofphotograph, Meran, The Zemplén Museum

Andreas Hofer, in hiding, was betrayed, captured by the French, executed by firing squad in Mantua on 20 February 1810 on Napoleon's direct orders and made into a Tyrolean martyr.

Top: Albin Egger-Lienz, Ein Abschied in Tirol im Jahre 1809 / A farewell in Tyrol in 1809, 1894.

Bottom: Albin Egger-Lienz, Nach dem Friedensschluss 1809 / After the peace settlement 1809, 1902. The defeated returning home.

What singled out this romantic-religious mountain people was its remarkable resignation in death. There is not a single example from the several people who were executed by courts-martial of anyone who died without showing the greatest steadfastness and courage. It was the complete surrender to the will of God and their own religious faith and their belief right up to the last moment that saw their own death as martyrdom.

Equally remarkable is the fact – evidence of their pure German ancestry – that from the moment the whole people came to the acceptance of their complete subjugation there was no hostility, no assassination, no mistreatment of individual soldiers. Despite the complete impoverishment of the class who had so far lived only from war there was no robbery or theft, even though individual soldiers and officers of the Bavarian army passed through the remotest valleys and houses. A general muffled silence, a general dolefulness in the country were the only traces of the war that had just ended.

Baur, Carl von. Der Krieg in Tirol während des Feldzugs von 1809, München, 1812, p. 172f, quoted in [Kern 44]. Baur was an officer in the Bavarian army.

Senn had desperately tried to make a last minute peace treaty with the Bavarians, but finally they forced this curmudgeonly, troublemaking lawyer in 1810 to sell his house and belongings within the space of a few days to intermediaries at a large financial loss and move to exile in Vienna, where he became a magistrate.

Unfortunately, his last-minute attempt to engage with the Bavarians in order to avoid needless bloodshed made him suspect in Vienna and some say that he was placed under police observation. Eventually, in 1815, the Congress of Vienna would reinstate Tyrol to Austria and the emperor who had betrayed it.

Michael Senn did not live to see that moment, he died in 1813 of Nervenfieber, typhus. The violent passions in Tyrol had seethed on and spread to wherever Tyroleans were, so much so that the rumour was spread later that Senn had been stabbed to death by a political opponent.

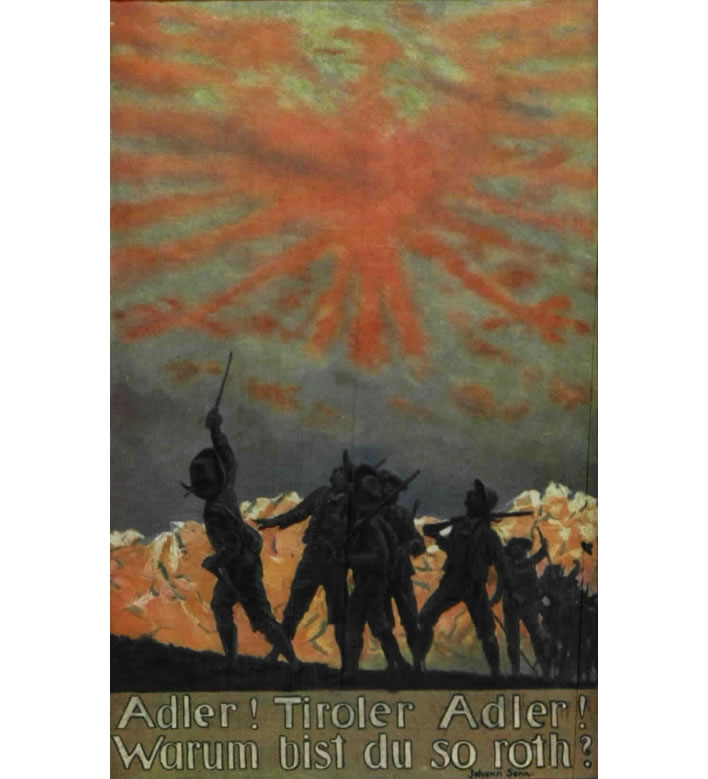

The red Tyrolean eagle

Michael Senn's son Johann had already been in the Stadtkonvikt six years at the time of his father's death. In 1809, we are told, the 14 year-old Johann Senn wrote the poem that would be his greatest – and only – hit: Der rote Tiroler Adler. I have never seen any evidence for this dating. If the date is correct, then it must belong to the early part of 1809, before the Napoleonic/Bavarian nemesis arrived.

| Der rote Tiroler Adler | The Red Tyrolean Eagle |

| Adler! Tiroler Adler! | Eagle! Tyrolean eagle! |

| Warum bist du so rot? | Why are you so red? |

| Ei nun, das macht, ich sitze | Well now, that's because I sit |

| Am First der Ortlesspitze, | On the ridge of the Ortler |

| Da ist's so sonnenrot, | Where it's red with the sun, |

| Darum bin ich so rot. | That's why I'm so red. |

| Adler! Tiroler Adler! | Eagle! Tyrolean eagle! |

| Warum bist du so rot? | Why are you so red? |

| Ei nun, das macht, ich koste | Well now, that's because I drink |

| Von Etschlands Rebenmoste, | From Etschland's wine, |

| Der ist so feuerrot, | Which is as red as fire, |

| Darum bin ich so rot. | That's why I'm so red. |

| Adler! Tiroler Adler! | Eagle! Tyrolean eagle! |

| Warum bist du so rot? | Why are you so red? |

| Ei nun, das macht, mich dünket, | Well now, that's because, I think, |

| Weil Feindesblut mich schminket, | The enemy's blood adorns me, |

| Das ist so purpurrot, | That is so purple-red, |

| Darum bin ich so rot. | That's why I'm so red. |

| Adler! Tiroler Adler! | Eagle! Tyrolean eagle! |

| Warum bist du so rot? | Why are you so red? |

| Vom roten Sonnenscheine, | From red sunshine, |

| Vom roten Feuerweine, | From red fire wines, |

| Vom Feindesblute rot — | From the red blood of the enemy — |

| Davon bin ich so rot! — | From that I am so red! — |

Notes on the poem: The Ortler ('Ortles' in Italian) was the highest mountain in the Tyrol, but now is part of South Tyrol. Etschland, the valley of the river Etsch, is now also part of South Tyrol. The text used here is that of Johann Senn's Gedichte, Poems, Innsbruck 1838.

Do not be misled by the superficial simplicity of this poem: it is a masterful recreation of the style of the Volkslied, 'folk poem', that was coming into vogue around 1809. If Johann Senn wrote this as a 14 year-old in the Stadtkonvikt he deserves great respect.

Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the iconic collection of 'folk poems', had been published between 1805 and 1808. The general opinion among literary critics today is that that anthology represents the starting point of the Romantic Movement in German literature. Few of the poems in the anthology were completely genuine 'folk poetry'. The authors of Wunderhorn, Clemens Brentano (1778-1842) and Achim von Arnim (1781-1831), either made up the poems from scratch or, more usually, cobbled them together from fragments they found in older sources. They were quite brazen in doing this, even adding fake attributions.

Brentano and von Arnim put a lot of effort into writing 'authentic' folk poetry and either one of them would have been proud had they written something as good as Senn's piece – although it would have been too political for Wunderhorn. The swots reading this blog will recall Wilhelm Müller's effort in the two 'Schubert' verse cycles, Die schöne Müllerin and Die Winterreise (less so) to write 'rustic' verse.

Senn's Der rote Tiroler Adler is a textbook example of the rustic poem: the repetitions, the simple language, the colloquialisms (Ei nun, das macht), the short lines. It's also a song of triumph, not disaster, and as such would be just the thing to cheer up Tyrolean hearts after 1809 – and, indeed, after all the disasters that afflicted Tyrol in the 20th century. The proof of the pudding in the case of Senn's piece is its popularity from the late 19th century onwards, particularly – it should be noted – outside Tyrol.

A postcard from the First World War: Adler! Tiroler Adler! Warum bist du so roth? Image: ÖNB.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!