Revolting students

Richard Law, UTC 2017-04-24 16:44

A picture of paranoia

The disaster that would ruin the life and career of Johann Senn only makes sense to modern readers when it is seen against its historical background, a background that consists of layers built up one on top the other, like that of a painting.

Germany in tatters

The bottom layer, the gesso ground if you like, of our painting takes us back to the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Thirty years of misery: bitter religious factionalism mixed with feudal opportunism, battles, plunder, famines and disease. That disaster was ended – 'resolved' would be an overstatement – by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

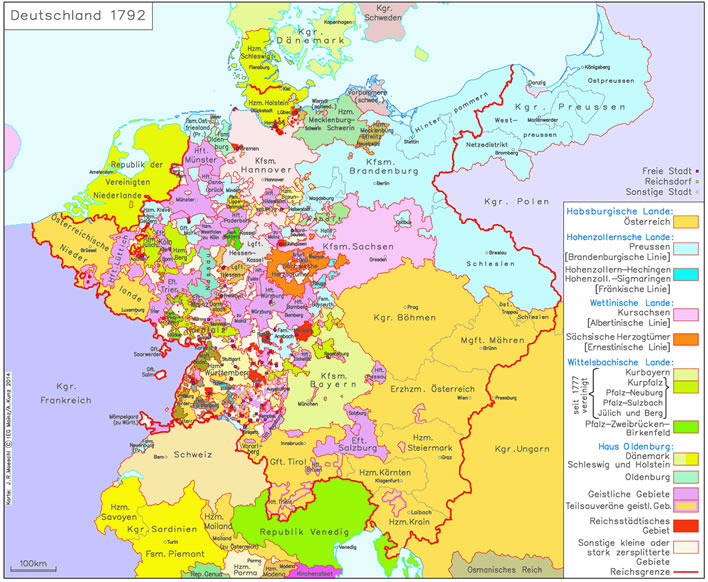

That treaty left German-speaking Europe in tatters – the word 'patchwork' is really too dignified to describe this assembly of scraps of feudal statelets, each with its duke or princeling. The German-speaking peoples had a linguistic, cultural and intellectual identity that transcended this political mess. Even two centuries after the treaty the great German writer Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) would note that the Germans had 'three dozen rulers'. [Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen, 1844, Caput XI, l.38, p.33].

Map of the European patchwork in 1792. This is the year of the accession of Franz II/I to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. Image: IEG-Maps.

We now need to add a further layer to our background: German political weakness. That jumble of scraps, the German 'cultural nation', was left politically divided and fundamentally helpless. True, the largest of the scraps, Prussia, was a force that could not be ignored, but it was still only one element among many.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), during the twenty years before his final defeat in 1815, was able to humiliate the scraps more or less at will. The patriots of the German-speaking world were shocked at the signs of weakness that the Befreiungskriege, 'Wars of Liberation' against Napoleon had laid bare. The French continued their humiliation of the scraps even after Napoleon was gone, thus sowing the seeds of the great European conflicts of the 20th century.

But the desire for political unification of the scraps had a corollary: the desire for political reform. The nation that would arise when the scraps were finally stitched together could not be just another feudal imperium. This new German nation would have to be a constitutional state under the law with rights and freedoms for its citizens.

And now one more layer must be added to our background: the sense of German identity. During the two centuries after the Treaty of Westphalia the dukes and princelings of the German-speaking scraps had vied with each other to emulate the extravagances of the Bourbon court in France under Louis-the-this and Louis-the-that. In their courts and amongst themselves they spoke French, believing they were speaking the language of civilisation and culture. German was the language of the common people and therefore acquired a politically democratic aspect.

The author of the poem Die Forelle, Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart (1739-1791), arguably the first German journalist in the modern sense of the word, mocked the Bourbonesque tyranny, extravagance, immorality and affectations of Carl Eugen Duke of Württemberg (1728-1793), whilst praising the down-to-earth honesty and simplicity of the German population. He was finally hooked by the Duke and his persiflage cost him ten years in a fortress prison.

But from the middle of the 18th century the high culture of Europe became more and more German, too; the great writers – Lessing, Goethe, Schiller, Herder, Wieland and many more – and the great philosophers – Kant, Hegel, Fichte, Schelling and many more – were writing in German. A great and subtle German culture arose based on a great and subtle German language, all spread across these politically feudal scraps. [see Heine, Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland, 1834, passim.]

And yet another layer needs to be added to our background: academic unrest. The horizon of the farmer and the peasant is the field boundary, that of the intellectual is the German-speaking culture that encompassed most of middle Europe. The discontent of the intellectuals of the German tribe at the political helplessness of that culture was particularly strongly felt among many of the students of German universities. In turn this discontent set the ideological tone for the student societies that had evolved in universities, the Burschenschaften, roughly: 'young men's associations'.

The Burschenschaften displayed all the usual trappings of social identity: shared ways of dressing, symbols, oaths and a sense of loyalty. Their members felt that powerful emotion: belonging – not only to their own association but to the many others throughout the German world. No one will be surprised to hear that these clubs of young men had a hang to passionate excess in their behaviour as well as in their ideas which manifested itself in rowdiness, drunkenness, dangerous pursuits and general disorderly conduct.

And finally we add the last layer to our background: repression. After Napoleon had been definitively defeated, the Congress of Vienna was held in 1815 to re-establish the lost order of Europe. The norm of political life was considered to be the conditions that existed before they had been so rudely interrupted by the rabble of the French Revolution and that upstart lieutenant. Now that Boney was sitting safely on his distant island the Austrian Foreign Minister, Prince Metternich, bound the dukes and princelings of the scraps together into the Deutscher Bund, the 'German Confederation', in the hope of mutual self-preservation. The clock would be turned back.

The murder of Kotzebue

Despite the attempts of the Congress to impose political calm throughout the statelets of Europe there was one political element that was still churning: the Burschenschaften. Their activities could just be viewed by the authorities as a public order problem arising from youthful excess. Until, that is, a theology student at the University of Jena, Carl Ludwig Sand (1795-1820), a prominent Burschenschafter, stabbed to death the popular writer August von Kotzebue (1761-1819) on 23 March 1819.

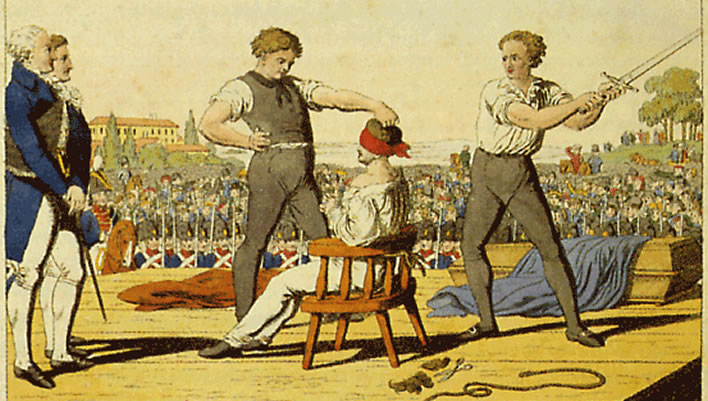

Sand's murder of the hapless writer Kotzebue, whom he alleged to be working as a paid agent for Russia, was an act of derangement. He paid for it by being publicly executed by beheading with a sword.

The execution of Carl Ludwig Sand in Mannheim on 5 May 1820.

It was, though, a trigger for Metternich to impose in August 1819 the Karlsbader-Beschlüsse, the 'Karlsbad Agreements' across the German-speaking world. The dukes and princelings of the scraps agreed to support each other in censorship and repression. Thirty years before, the murderous fanatics of the French Revolution had toppled a monarchy and a state. That could not be allowed to happen again.

In June 1819, even before the Karlsbad Agreements, Kotzebue's murder had triggered in Germany a wave of dismissals of professors and students, together with arrests and confiscation of writings.

The reaction in Austria was at first calm. The measures now imposed across the German statelets were nothing new in Austria: they had been applied ever since 1803, when Franz II/I had put the final touches to his police and censorship system.

Police activity during the rule of Franz II/I, Metternich and Sedlnitzky was an everyday event. It could strike almost anyone. The interception of Johann Schärmer's letter in 1813 to his father about the death of Michael Senn is just one tiny example of the culture of fear that emanated from the fearful Emperor Franz, which brought a belljar of suspicion, censorship and repression down on the Austrian Empire.

For well over a century historians have used lazy expressions such as 'Metternich's repression' or his 'system' to describe this period. It was in fact Emperor Franz's system. He had started developing it immediately after his accession in 1792 and continued its development as the years went by. Prince Metternich, Count von Sedlnitzky and all Franz's other myrmidons were merely subordinate elements of that system.

As a first reaction to Kotzebue's murder the Austrian police concentrated on identifying German students in Vienna and spying on visiting German academics. Austrians were not allowed to study at German universities.

This was the calm before the storm, because it soon became clear to the authorities that German revolutionary thinking and organization had also spread among Austrian students, not just in Vienna but also in Salzburg, Linz, Graz and Innsbruck. When the trigger to act came, the Austrian police were prepared.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!