The Kaiserbrunnen in Konstanz

Richard Law, UTC 2018-06-28 09:44

To Konstanz. 'Pearl of the Bodensee' – or is that Meersburg? or Romanshorn? or Friedrichshafen?

No, definitely not Friedrichshafen.

And should we write 'Konstanz' or 'Constance', 'Bodensee' or 'Lake of Constance'?

Who cares? Sometimes this, sometimes that – our wise readers will sort it all out.

Once in Konstanz we go to the Marktstätte, the 'Market Place' just by the ferry harbour. A few steps further and there we have it: The Kaiserbrunnen, the 'Fountain of the Emperors'.

For twenty-five years the Kaiserbrunnen has been impressing visitors with its scurrilous and witty treatment of its eponymous subjects: three medieval German emperors. There is much more to it than that, though. So, a quarter century after it was constructed, it's high time for a closer look.

Hans Baur's Kaiserbrunnen

What the visitor sees today is in fact at least the third fountain at this spot. The second fountain, the original Kaiserbrunnen, came into existence in 1892, when its artist, the local sculptor Hans Baur (1829-1897), won the competition to replace the then dilapidated fountain in the Marktstätte.

Baur created a four-sided stone stele – a red sandstone obelisk in the centre of a granite fountain basin – that would house on each side a statue of one of four German emperors, each of whom represented one of the great ruling dynasties of German history: Heinrich III (Franks), Friedrich I 'Barbarossa' (Hohenstaufen), Maximilian I (Habsburg) und Wilhelm I (Hohenzollern). So far, so traditional.

The fountain was completed and unveiled on 30 October 1897, 121 years ago. Bauer never saw it finished – he died six months before its completion, on 5 June of that year. Here are some photographs of it taken from postcards:

Two postcard images (undated) of Baur's Kaiserbrunnen. The lack of motor transport and the presence horse-drawn carriages suggest that the photographs were taken in the late 19th or early 20th century, not too long after the erection of Baur's fountain in 1897.

The lower image is a detail taken from the top image showing the Kaiserbrunnen. The locals appear to have done their best with flower boxes to cheer up Baur's austere construction. The dating is difficult, but we can be sure that we have entered the motor age completely by this time. We might guess that the pennants or banners are in the black-white-red colours of the German Empire. This was the official colour combination of the flags of the German Empire from 1871 until 1919. Although Weimar Germany introduced the black-red-gold flag, black-white-red colours were still tolerated. The colour scheme came back again with the founding of the 'Third' German Empire by the National Socialists in 1933, who wanted to shed every association with the detested Weimar Republic. It seems unlikely that this is a photo taken before 1919. There also seem to be two banners with swastika symbols(?), which would date the photograph to some time after 1933 – but not long after, since the banners would then all carry swastikas. The puzzle of what special occasion it was that caused so much flag flying has to remain unsolved.

Another postcard image from around the same time as the previous images, possibly somewhat later.

Germania arise!

Baur's choice of emperors for his 'Fountain of the Emperors' has to be understood in the context of the rebirth of the single German state under Prussian leadership at the end of the 19th century.

The presence of the Johnny-come-lately Hohenzollern Wilhelm I (1797-1888, first German Emperor 1871) in the company of the three medieval emperors is a brazenly political gesture to the emerging German nationalism of the time. After the German triumph over the French in the Franco-Prussian war of 1871, Wilhelm I had become the first emperor of the newly proclaimed Reich. He had died only four years before theKaiserbrunnen project was initiated, by which time the successor was Wilhelm II, 'Kaiser Bill' himself. And we all know what happened under his rule.

Baur's Kaiserbrunnen was a political and propaganda gesture that attempted to portray the roots of Wilhelm I's German empire reaching back into the medieval period, a period to which many Germans looked back as the last time that Germany was a proud, unified nation before it was torn apart by the Reformation and the Thirty Years' War. The three other emperors alongside Wilhelm came from that antediluvian period: Friedrich I, emperor 1155; Heinrich III, emperor 1046; Maximilian I, emperor 1508.

The emperors at war

Baur's figures were created using the electrotyping technique, which deposited a layer of metal (mainly copper) onto a positive or negative mould. The artist could work easily in wax or plaster, after which the electrotyping process created a perfect replica in metal. Electrotyped sculpture used much less metal than traditional bronze casting.

Despite the relatively small amount of metal in Baur's figures, in 1942 they were removed and melted down for the war effort. All that remained was the stone stele, which stood in that state for nearly fifty years.

A postwar image of the Marktstätte. From what little we can see of one of the alcoves of the Kaiserbrunnen it appears to be empty.

Decline and rebirth

During the second half of the 20th century the destiny of Konstanz was clear. It had become an adjunct of Switzerland. It is located on the border between Germany and Switzerland, that is, right on the southern edge of Germany. Worse, it lies at the end of a peninsula, from where there is nowhere else to go but Switzerland.

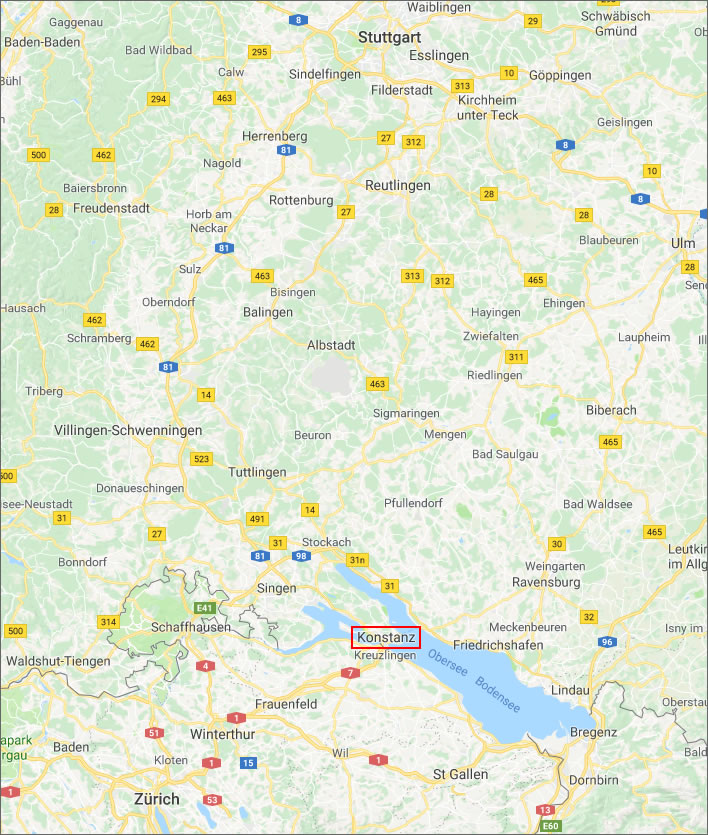

On the road to nowhere: Konstanz on the tip of the peninsula. The nearest half-decent motorway connection to the rest of Germany is in the vicinity of Singen. Image: Google Maps.

The few industries in Konstanz were in decline. Once road transport became king their fate was sealed. The environmentally sensitised inhabitants of the university town did everything they could to stop the hated motorised traffic, which means that this peripheral town still has no fully motorway-standard link to the rest of Germany even today. It is still much easier to get to Switzerland than it is to get to Germany.

During most of that period the Swiss had a lot of buying power and went shopping in Germany, where many things were cheaper – particularly upmarket goods. By the 1990s it was clear that no sane company would start a business of any size in Konstanz, so its future would be as a shopping and tourist town.

As part of this future, the Marktstätte, opposite the harbour with its ferry services and close to the railway station, was to be turned into an attractive place for visitors. The revitalised Kaiserbrunnen would play its part in that plan.

Barbara and Gernot Rumpf's Kaiserbrunnen

In 1990 the bare fountain obelisk that had been left after the scrap metal raid in 1942 and its surroundings were decorated with sculptures done by Professor Gernot Rumpf and his sculptress wife Barbara. The project was finished in 1993.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

The days of the respectful treatment of imperial might had gone. The view from the 1990s, after a century of grim history in Germany, was unsurprisingly quite different to that of the emergent German superpower at the end of the 19th century.

For the Rumpf fountain, two of the emperors in Baur's selection were reinstated, the Staufer Friedrich I and the Habsburger Maximilian I; two were dumped: the Frank, Heinrich III and the Hohenzollern, Wilhem I. The fourth niche was left empty as – 'the future' –. Here are some context views of the Rumpf Kaiserbrunnen taken a few days ago (24.06.2018).

All images: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

In the spirit of the times the new fountain is much more family and tourist friendly than its predecessor. A particular feature is a ground-level assembly of cute mythical animals associated with the Lake of Constance, notably the Seehase, the 'Lake Rabbit', with the head of a rabbit and the tail of a fish. There is also an eight-legged bronze horse onto which visitors can climb, its saddle polished by a million bottoms of all nations, offering the perfect photo-opportunity.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Let's look at the emperors who give the Kaiserbrunnen its name.

Friedrich I, 'Barbarossa'

The Staufer Friedrich I, (Barbarossa) (1122?-1190, Holy Roman Emperor 1155) had been on Baur's stele, but re-emerged in the Rumpf reincarnation in a very different form.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

He is wearing the unmistakeable Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, here dramatically prominent. His beard – alluding to his nickname 'Red Beard' – was in historical tradition a rather dainty one, but here has been extended with what seems to be at first glance a grotesque neck-beard.

Looking more closely, it is clear that this is no beard. The lines and gravity of it make it appear more like the worm-like body of an invertebrate that descends from behind the emperor's goatee. And what is the head of the fish on one side of the block behind Friedrich and the bones of its tail on the other side of the block doing here?

German medievalists ride to our rescue. They remind us – as if we had ever forgotten! – that Barbarossa died on a crusade in Anatolia (now south east Turkey). After sacking the city of Iconium (Konya) he drowned in the river Saleph (Göksu) on 10 June 1190. The reason he drowned – that is, the reason why he was in the river in the first place – is unclear. It seems, therefore, that the presence of the fish alludes to Friedrich's watery end.

No one knows where Friedrich's remains are. According to an old Germanic tradition, particularly applicable during foreign adventures such as wars and crusades, the innards of the dead person were disposed of and the rest of the body was pickled and boiled until all the flesh fell from the bones. The bones were the important things and were carefully preserved – they were considered to be the necessary basis for the resurrection of the dead.

Once we recall this, the allusion in the sculpture to Friedrich's boneless, boiled body now drooling gelatinously down from his head is now obvious, as is the unhappy-looking fish being turned into a bony skeleton in some sort of cooking pot behind the great man. The fish goes in, the flesh drools down and the bones emerge.

The Cappenberger Barbarossakopf, which seems to have served as the Rumpfs starting point for their startling caricature. The gilded bronze head was noticed in 1882 in Schloss Cappenberg and first associated with Friedrich I by the historian Friedrich Philippi in 1886 – an attribution that is still not universally accepted, however. The head was created in western Germany around 1160. Photograph: Münster, Bischöfliches Generalvikariat, Kunstpflege/Stephan Kube Gräven.

Certainly not the most respectful representation of Friedrich Barbarossa, who occupies a key place in Germanic mythmaking. According to the myth made popular by the Brothers Grimm and the 19th century poet Friedrich Rückert – but mocked by Heinrich Heine among others – Barbarossa never died but is merely sleeping under the hills of the Kyffhäuser mountain range in Thuringia, awaiting the moment when he will awake to lead Germany to the restoration of its greatness.

On the death of Wilhelm I in 1888, who was, you will recall, one of the other emperors on Baur's original stele, a monument to Barbarossa was erected on the Kyffhäuser mountain between 1890 and 1896, just around the time work was proceeding on Hans Bauer's monument. The monument was principally to Wilhelm, of course, and was just another effort at associating the two 'founders' of the German Empire across a gap of 700 years.

On the edge of the basin, in front of each of the three emperors, is that emperor's seal. This is Friedrich's seal. He is holding the imperial orb and sceptre. Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

It takes little imagination for those who know the history to burst out laughing at the Rumpfs' wonderfully iconoclastic representation of the boiled-fish Friedrich, the great Barbarossa, as a gelatinous dribble: 'But doth suffer a sea-change, into something rich and strange' ( Tempest 1:2). Satire at its finest.

You don't think that the Rumpfs are mocking Baur, his emperors and the entire myth of renascent imperial Germany, do you?

Maximilian I

The emperor on Friedrich's left is the Habsburger Maximilian I (1459-1519, Holy Roman Emperor 1508). In his representation we see little of great importance. The pigeons seem to like him. His image is reminiscent in a general way of Durer's famous portrait of him from 1519.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Over his shoulders he is wearing the 'Spanish Cloak', a half cloak which partially exposed the left arm. The Spanish Cloak was an important part of the courtly mannerisms of the Habsburgs, particularly in the Spanish branch. In Austria its use was dispensed with by the Austrian Habsburgs from about the middle of the 18th century.

The cloak is held together by the clasp variant of that other great innovation of the Habsburgs, the Order of the Golden Fleece. As we have already noted on this website, the Order was one of the defining accoutrements of the male members of the House of Habsburg.

The real interest in the representation of Maximilian on the Rumpf fountain is the tense distance in the relationship between the Emperor up in his niche and the bust of his second wife, Bianca Maria Sforza (1472-1510) down on the parapet.

Maximilian's first wife had been the Archduchess Maria von Burgund (1457-1482), whom he had married by proclamation on 21 April 1477 (ceremonially on 19 August 1477). She died on 27 March 1482, only 25 years old, from the consequences of a riding accident. Maximilian seems to have loved her, for on his own death his heart was placed in her sarcophagus.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Maximilian married Bianca on 30 November 1493 (ceremonially on 16 March 1494). It was a marriage of money, not love.

There was a considerable hierarchical distance between the Emperor and Bianca, which caused some criticism of the marriage from the outset. This mood is captured in the de haut en bas relationship of their figures on the fountain. In addition, Maximilian seems to have found his wife intellectually very limited, but this may be just Maximilian blackening his wife's reputation.

But all that was easily overlooked at first, because the best thing about the relationship for Maximilian was that Bianca came with an enormous dowry of 400,000 ducats in cash and a further 40,000 ducats in jewels. The permanently cash-strapped Maximilian could hardly refuse, however dim and low-bred she was.

In the production of children she also failed him, even though Maximilian was a very successful breeder with his mistresses. After about six years the marriage was all over except in name. Even the flow of money stopped when Bianca's rich uncle Ludovico Sforza, who had bankrolled the marriage, lost his possessions in 1499.

She died on 31 December 1510 in his absence. He did not even visit her funeral service or erect a gravestone for her.

On the parapet of the Kaiserbrunnen she has her back to him. From time to time the bird-like creature perched on her head spews out a stream of water on to Maximilian's outstretched hand – presumably representing the flow of cash from the Sforza family that kept Maximilian's Imperial Court afloat for many years. The details are not entirely clear, but it is said that whenever he travelled he left Bianca and her court behind as a guarantee for his creditors.

Otto I

A worthy third emperor, the Saxon Otto I (912-973, Holy Roman Emperor 962), sometimes called 'the Great', was added by the Rumpfs. He is the earliest of the three emperors.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Whereas the two emperors taken over from Baur's stele are the subject of mockery, the emperor selected by the Rumpfs is a model of decorum. His image is relentlessly positive and unmuddled by deeper symbolism.

The facial features which the Rumpfs have given to Otto I are well delineated – noble, without a trace of satire or caricature. The iconography is that of the imperial ruler: the crown, the sceptre, the orb. He is not wearing Habsburg regalia, of course, because he was no Habsburg but a Liodolfinger: such trinkets were thought up well after his time. Like Maximilian's bust, the cloak curves around him, but the differences stand out: it is not the heavy Spanish Cloak and the clasp holding it together is not the seal of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

His reign, though tumultuous, led to the creation of the wider Holy Roman Empire, the transition of rule to his son was peaceful and well-regulated.

The reign marked the beginning of an era of peace and progress that is called the Ottonian Renaissance, since it encompassed the three successive Ottos – Otto I (936-973), Otto II (973-983) and Otto III (983-1002) – and so lasted thirty years after his death.

His marriage to Adelheid von Burgund (931?-999) was not only a dynastic masterstroke, it seems to have been a relationship of great affection. She was not a cipher to this great king, either. Her great works for the Catholic Church and her lasting reputation of piety, humility and her works for the poor led to her sanctification in 1097, nearly a century after her death. Her feast day is 16 December, for the pious.

She may be represented in the Rumpf portrait as the little bird with the plaits on Otto's shoulder who seems to be talking into his ear. This seems a very minimalist representation of her influence, but it is a positive one. The birdlike creature on Otto's shoulder is very similar to the birdlike creature on the head of Bianca Sforza which from time to time spews out money into Maximilan's outstretched hand.

Perhaps the satire in Otto's case is the very presence in the group of this great emperor, one of the greatest of them, who was left out of Baur's collection for his Kaiserbrunnen.

The future

The niche where a fourth emperor once stood is now a closed pair of doors. It may be that the implication is that at some future point the doors will open and a new emperor will arise. This seems a far-fetched interpretation.

The Rumpfs labelled this niche on the water outlet beneath it 'FUTURUM' [the Latin nominative neuter singular of futurus, meaning 'the future', not the German das Futurum, which, with the more modern das Futur, is only used as the name of the future tense].

It seems more likely that the closed doors indicate that the position of 'emperor' is now closed. The future as envisaged at the end of the 20th century is that there will be no more emperors – in these days of constitutions, democracies, republics and globalisation they are now surplus to requirements, at least on the European scale. In global terms, dictators are the modern thing – we have plenty of those. Emperors, though, are in short supply.

Would we be taking interpretation too far if we saw the bird emerging from underneath one of the doors as being a dove, the universal symbol of peace? Unlike all the other birdlike creatures that the Rumpfs have created it has the form of a real bird, not some mythological creature.

Pacifists – and there were a lot of them in Germany in the second half of the 20th century – will look at the three blood-soaked despots occupying the other niches, rulers whose reigns were filled with battle and conquest, and they will shudder; they can only hope for that time to arrive when the dove of peace finally emerges.

But the optimism for the future is unmissable: at some time the dove will emerge and plume for flight – we see its wings raised in readiness. How different in spirit from the four warrior emperors on Baur's original Kaiserbrunnen!

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

The outer circle

The sculptures around the rim of the pool add historical aspects to the figures of the emperors above them. Just as the rim surrounds the obelisk, they are also features from the historical surroundings of the emperors.

The feudal estates

On the diagonal that runs down from Otto I's right we find a pair of birds squawking up at him:

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

One of the birds is decorated with crucifixes and is wearing a mitre on its head. The figure clearly represents the power of the Catholic Church and particularly the Pope in medieval times.

The other bird is wearing the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire, unmistakeable with its unusual eight-sided shape, having a prominent cross at the front and the notable arch. This was the same sort of crown that we saw on Friedrich I's head. The creation of the crown is traditionally attributed to Otto I, but it is the bust of Friedrich that is wearing a large-size example.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

The two birds thus appear to represent the two feudal estates of the realm, the clerical and the aristocratic. There was a third estate in the medieval feudal system, the peasants (or, less misleadingly, the free farmers). This estate is represented here by the tiny mouse, crouching, perhaps even asleep, its back turned to the great emperor, or perhaps hoping not to be noticed.

The three popes

On the diagonal that runs down from Friedrich I's left we find a strange three-headed peacock-like creature:

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Each head is wearing a papal tiara, the hat with three crowns (the 'triregnum', shown here suggested by lines scratched around the circumference) in the style worn by late medieval popes. The fact that there are three heads and three tiaras is an allusion to the Council of Constance, which was held in Constance between 5 November 1414 and 22 April 1418.

The council was called primarily to resolve the so called 'Western Schism', which by the time of the opening of the Council had brought three popes into existence: Pope Gregory XII; an 'antipope', John XXIII and a second antipope, Benedict XIII. After much to-ing and fro-ing both Gregory and John stepped down, making way for the election of Martin V as the one true pope in 1417. Benedict dug his heels in and was excommunicated. Benedict and his followers would keep up the resistance for about another ten years, after which Martin V was finally recognised as the single, universal pope.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

The Council of Constance has a firm place in the history of Konstanz– in some ways it was its highpoint – and so the allusion to it on the Kaiserbrunnen is justified, even though it has nothing directly to do with any of the emperors represented.

Die Konstanzer Friede

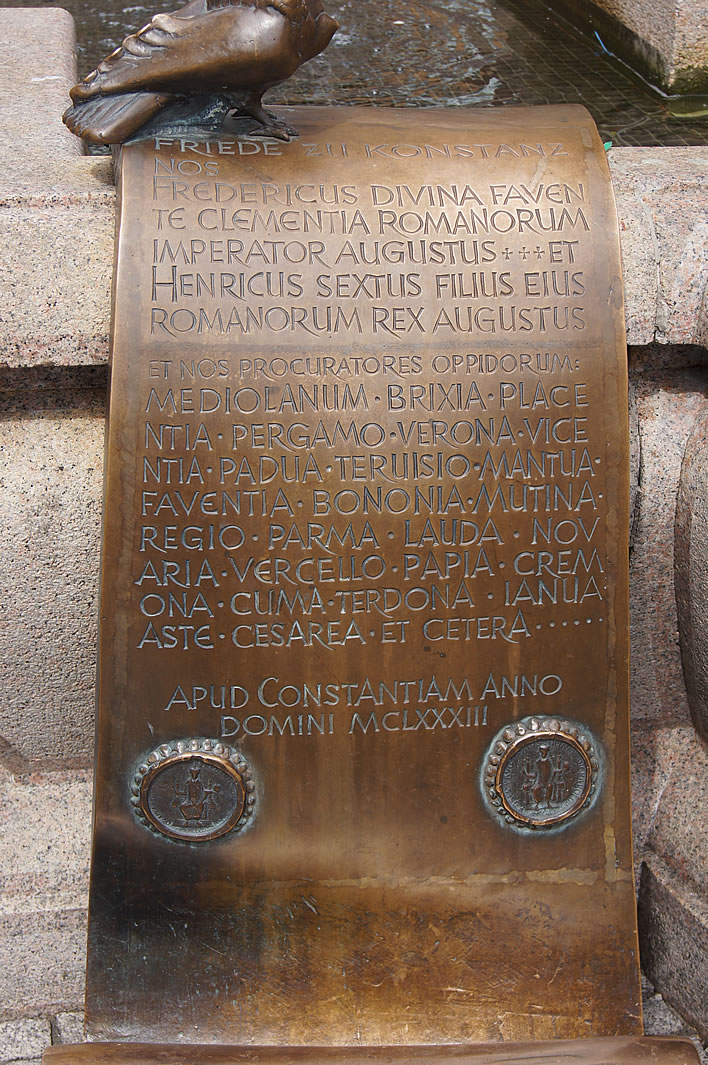

Another piece of the history of Konstanz we find at the diagonal from Friedrich I's righthand side: a bronze scroll representing the Friede zu Konstanz, the 'Peace of Constance', concluded on 25 January 1183 by Friedrich and the Lombards.

Historians to this day are still debating the exact implications of the treaty, but its main consequence was that it bought Barbarossa some time to go to the aid of the Pope in several conflicts elsewhere. It also granted considerable political and administrative freedoms to the city states of the Lombardy, thus laying the foundations for their renaissance power. The scroll contains the Latin preamble and the list of signatories to the agreement:

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Frederick, by divine mercy emperor of the Romans, Augustus, and Henry VI, his son, king of the Romans, Augustus …

The conclusion is a list of the cities of Lombardy assenting to the agreement, the date 'at Constance in the year of Our Lord MCLXXXIII' and the seal of Friedrich I and his son Henry VI.

A wildly fanciful representation of the treaty scene with a fine Teutonic representation of Barbarossa that is nothing like the Cappenberger Barbarossakopf can be seen in a fresco in the front of the Rathaus, the 'Town Council' in Konstanz.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Returning to the Kaiserbrunnen, we only need to add that it was Otto I who secured northern Italy for the Holy Roman Empire and it was Friedrich I who nearly lost it again.

The female principle

Perched at the top of the scroll is another female, bird-like creature, apparently squawking at Friedrich. She is the third creature in this style on the Kaiserbrunnen: one is perched on top of Bianca Sforza's hat, occasionally spewing water into Maximilian I's hand; another is perched on Otto I's shoulder, singing into his ear. All three have braided hair, possibly an allusion to something Teutonic –who knows? Let's call them the 'female principle' to cover up our ignorance. The modern version is in the background of the photo looking cool and eating an ice-cream, her hair unfortunately not braided.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

The hare

The Rumpfs have placed a hare in the corner of the basin close to the bust of Bianca Sforza. Like the birds, it has two plaits. The hare is a traditional symbol of fecundity. If this symbolism is valid in the present case, then the reason it is placed close to Bianca Sforza – who produced no children for Maximilian, we recall – is a mystery. Perhaps the hare is there just for the fun of it – which is, after all, allowed.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

Finally, the artists have signed their work with a plaque containing two seals showing their initials, between them the word GESTALTUNG, 'Design', their names and their town, the date A.D. 1993 and two round and one rectangular cartouches containing ideogrammic inscriptions.

Image: ©Figures of Speech [re-use requires a link to this page].

How far we have come since 1897! We have here a Kaiserbrunnen which is simultaneously entertaining, is fun for the family and enriches the life of the street.

It provokes questions, which it does not always answer; it presents without explaining; it puzzles and amuses us – birds and rabbits with mighty Brünhild braids; it encloses deeper meanings, but we have to search for them. It is modern, postmodern, something to climb over, sit on, paddle in and photograph. There is some satire, some persiflage and ultimately a cutting mockery of its predecessor.

Just what the visitor needs when eating an ice-cream and looking cool in shades.

Now all that historical pondering is over it's off to the Münsterhof we go. Schnitzel und spätzle! Beer and bells!

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!