Schubert the Insignificant

Richard Law, UTC 2019-06-21 08:21

It is an enduring problem for the Schubert biography that its subject was a social nonentity for the whole of his life. That state of irrelevance continued for at least thirty years after his death. Schubert's 'greatness', 'fame' or 'significance' is an entirely modern phenomenon, one that really only came into being around the beginning of the 20th century.

The great and the good

The biographers of those people who attain fame in their own lifetimes can rely on the contemporary importance of their subjects to frame their tales. In life such people were the points around which events and other people revolved. In Schubert's day that significance was usually the result of an inherited feudal title and associated role – the emperors, the kings, the dukes and the counts – or very exceptionally it may have been acquired through particular talents or enterprise.

We should note in particular that social significance at that time always involved money: no pauper played any role in the history of those times.

Tempus loquendi, tempus tacendi. For a very few of these once important people time still speaks; for most, though, time is silent: a few contemporary greats became historical greats – the odd king, general or politician – but most were lowered into their crypts and graves and sank shortly afterwards into oblivion.

In a statement more focused on Schubert, we can say that most of the once significant people connected in any way with him have found oblivion. They are now known only unto God and perhaps only unto specialists of the period – and then mostly only superficially.

Imagine that we could transport some non-specialists from our own day back to Spaun's glittering last Schubertiade on 28 January 1828, the one that Moritz von Schwind reconstructed in his memory forty years later, and imagine we went round introducing the company to our moderns, what would be the reaction of our contemporaries? Bafflement. Who? The Imperial Court Controller of the what? Only when we got to the tubby little man sitting at the piano would there be a smile of recognition.

Moritz von Schwind's homage to a Schubertiade. This was drawn in 1868, 40 years after Schubert had died, and is therefore not a portrait of any particular event but more of a group portrait of the people in Schubert's life. Schwind left out the buffet table with the sausages and punch bowl.

And the corollary of this thought experiment is that, even if we know anything of those gilded ones at all nowadays, it is largely because of their association with that insignificant little man at the piano, Franz Schubert. Among every thousand moderns who have heard of Schubert, how many have heard of Joseph von Spaun?

The great and the good of Schubert's time, the lawyers, the imperial administrators, the minor aristocrats, the rent-seekers, the scribblers and the professors, all those with income and status and significance, all gone:

O dark dark dark. They all go into the dark,

The vacant interstellar spaces, the vacant into the vacant,

The captains, merchant bankers, eminent men of letters.

The generous patrons of art, the statesmen and the rulers,

Distinguished civil servants, chairman of many committees,

Industrial lords and petty contractors, all go into the dark,

And dark the Sun and Moon, and the Almanach de Gotha

And the Stock Exchange Gazette, the Directory of Directors,

And cold the sense and lost the motive of action.

Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 'East Coker', III, from 'Four Quartets' in Collected Poems 1909-1962, Faber, 1963, p. 199.

The Almanach de Gotha, indeed.

Growing in importance

The trajectory of Schubert's significance runs in quite the opposite direction to those of his once significant contemporaries. For his entire life he was socially insignificant. This lifelong insignificance was followed by a slightly longer period of insignificance after his death.

This means that in Schubert's case, history has reversed itself: Schubert is now one of the few stand-out figures of his age, whilst no contemporary of his has any significance in their own right for us at all now, unless, of course, they knew Schubert:

Ah, did you once see Shelley plain,

And did he stop and speak to you?

And did you speak to him again?

How strange it seems and new!But you were living before that,

And you are living after;

And the memory I started at—

My starting moves your laughter.I crossed a moor, with a name of its own

And a certain use in the world no doubt,

Yet a hand's-breadth of it shines alone

'Mid the blank miles round about:For there I picked up on the heather

And there I put inside my breast

A moulted feather, an eagle-feather!

Well, I forget the rest.

Browning, Robert. 'Memorabilia' (1855) in Collected Poems, John Murray, London 1919, p. 297.

The temptation for the modern biographer is to take Schubert's present significance and project it back into the times in which he lived. He becomes the centre of attention, as it were, when in fact he was never the centre of anything during his life. When the biographers became interested in Schubert thirty years or so after his death, how many of his 'friends' realised – late learning! – that they may still have the odd eagle feather in their minds or the drawers of their desks?

Karl, not Groucho

In order to achieve whatever limited understanding we can, we have to look at Schubert and his age through the eyes of the historian – particularly the social historian – not through the eyes of the musicologist or the music fan.

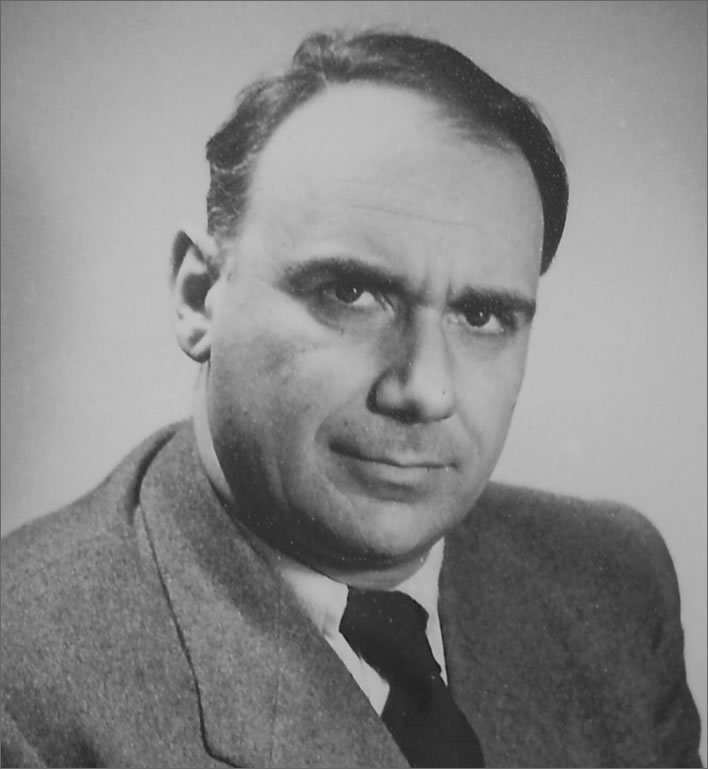

That said, the musician and musicologist Harry Goldschmidt (1910-1986), in his portrait of Schubert, approaches the historian's broader understanding of the age. Goldschmidt's mind was forged in the iron sociological shackles of Marxist theory, always aware of the fundamental importance of the material, economic and social basis for all art.

Harry Goldschmidt in 1951. One of the few Swiss people to emigrate from Switzerland, after his war service in the Swiss army, to the Soviet sector of Berlin (in 1949). Image: unknown.

Despite their more nonsensical, even mystical aspects, the analytical methods of Marxism have one great advantage: they never neglect the larger social and economic context; they never focus on the individual; they never look at the superstructure without also considering the base – the means of production founded on the technological substrate of society. You don't have to be a Marxist, though, to find suggestive the insights which that viewpoint offers:

Only against the background of a time that was already at its very core hostile to art, a time when victorious capitalism reached out its hand to tottering feudalism, can [Schubert's] rich life in the wealth of its details and singularity be understood.

Nur vor dem Hintergrund einer bereits in ihrem Kern kunstfeindlich gewordenen Zeit, als der siegreiche Kapitalismus dem wankenden Feudalismus die Hand reichte, kann dieses reiche Leben in der Fülle seiner Einzelheiten und Eigenheiten verstanden werden.

Goldschmidt, Harry. Franz Schubert, Ein Lebensbild, Henschelverlag, Berlin, 1954, p. 357.

At the risk of losing ourselves in a pretentious debating point whilst we are juggling all this Marxist terminology around, readers might like to reflect on Schubert's role as the individual, free-enterprise, free-market, laissez-faire creator and producer caught between the two tectonic plates of the failing feudal system and the growing large-scale organization of capitalism. Both feudalism and capitalism are ultimately antipathetic to the individual creator, whether shoemaker, baker or composer.

Let us be clear, though: our characterisation of Schubert's life as 'insignificant' is not to say that his life or his work was a failure, or that what he did was not heroic under the circumstances. It was just not important at the time:

It was a life, hemmed in by a reactionary provincialism that even poisoned a great city; a life for friendship, which appeared to him as the safest refuge against social oppression; a life marked by privation, pain and illness. But in this short, modest, unheroic existence that was rich in disappointments, Franz Schubert, the simple unspoiled man of the people, remained true to his last breath to the vital elements of his work: the good, the true and the beautiful.

Es war ein Leben, eingeengt in reaktionären Provinzialismus, der selbst eine Hauptstadt vergiftete; ein Leben für die Freundschaft, die ihm als der sicherste Hort gegen die gesellschaftliche Bedrückung erschien; ein von Entbehrung, Schmerz und Krankheit gezeichnetes Leben. Aber in diesem kurzen, anspruchslosen, an Enttäuschungen reichen und keineswegs heroischen Dasein ist sich Franz Schubert, der einfache unverbildete Mensch aus dem Volk, dem das Gute, Wahre und Schöne das Lebenselement seines Schaffens war, bis zum letzten Atemzuge treu geblieben.

Ibid p. 356.

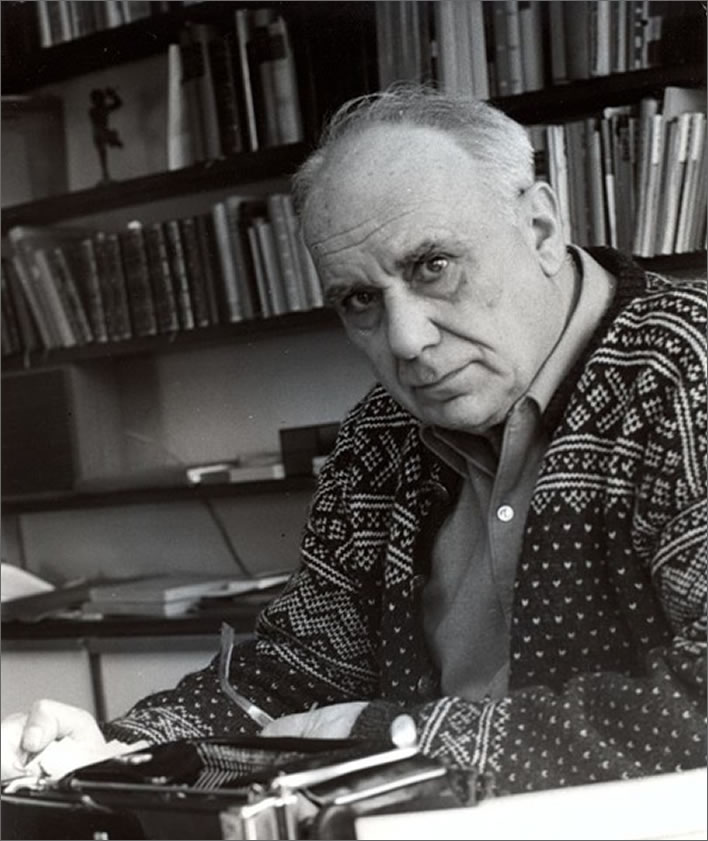

Goldschmidt in Berlin in 1985, the year before his death. Image: ©Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz.

Allowing ourselves a moment or two of overview combined with rhetorical hysteria, we could sum this up by saying that Franz Schubert was one small ant trying to stay alive and follow his lights in the churning 'anthill of Europe' [Ezra Pound, Canto 76, p. 458.], an anthill that was already disintegrating [Joseph Roth, Radetskymarsch, passim] but which would do so violently and definitively a century later (and its reassembled rubble once more two decades later).

A life at the margins

Some readers will object to our characterisation of the musical genius Schubert as an insignificant ant; others will perhaps say that Schubert's income over his lifetime was reasonable compared with what he might have earned in some minor musical post and that he certainly never starved in a garret.

Some censorious souls may even point out that Schubert's finances might have been in a better state had he not poured a lot of his income down his throat. These are the capitalists who would like to optimise the artist's productivity through the orderly life of the wage-slave's embourgeoisement.

These arguments miss the point: that it was only by grinding effort that he managed to maintain even that blessed state of just-about-surviving or its converse, just-about-not-starving. He had no regular income, no job title, no property, he wasn't even allowed to marry. His nominal employment at his father's school, which he maintained for a considerable period, was the only thing that preserved him from being thrown out of Vienna as a vagabond.

His status would appear to be a position close to zero on the significance scale, slightly below the skilled artisan but slightly above the war invalids and the widows begging in the streets of the imperial capital. He needed every friend and every lifeline he could get.

However you interpret the relationship between Franz Schubert and Therese Grob, however deep or shallow you care to make it, the fact is that in the end she married a baker, an artisan who, unlike Schubert, was allowed to marry her. Therese and Johann Bergmann both lived a good bourgeois life thereafter, a lifestyle which was utterly beyond Schubert's reach.

It is this insignificance that is the basis of the heroic aspect of Schubert's life. Ezra Pound once remarked bitterly on his own efforts to live as an independent writer: 'It takes a man of education to live without a fixed income' [the source will be added when I remember it!].

Schwammerl and friends

This problem is the special curse that falls on the biographies of those people such as Schubert who were social nonentities in their own lifetimes: the subject at their centre was never the centre of anything nor ever achieved anything that obtained recognition during their lives. What is there to write about?

But Schubert's biography offers a particularly egregious example of this curse, the notion of the Freundeskreise, the 'Circles of Friends'.

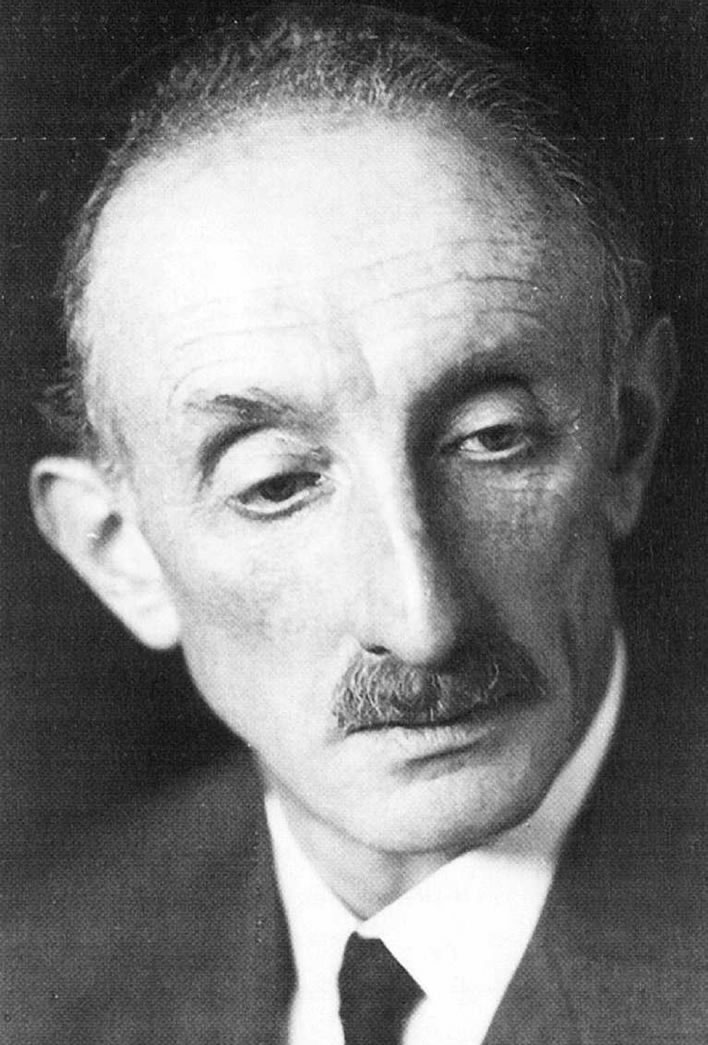

As far as I know, the term was brought into circulation as a literary conceit by the Austrian writer Felix Braun (1885-1973) in his book Schubert im Freundeskreis. Ein Lebensbild aus Briefen, Erinnerungen, Tagebuchblättern, Gedichten, which first appeared in the prestigious Insel Verlag in 1917, soon after the beginning of the Schubert boom. Extended into the plural Freundeskreise, 'Circles of Friends', the term went from being a literary conceit to a fixed star in the Schubert vocabulary.

Felix Braun, ND. Image: ©Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Wien.

It fitted the tenor of the times in which it appeared. The book was part of a series that Insel Verlag launched under the collective title Österreichisches Bibliothek, 'Austrian Library'.

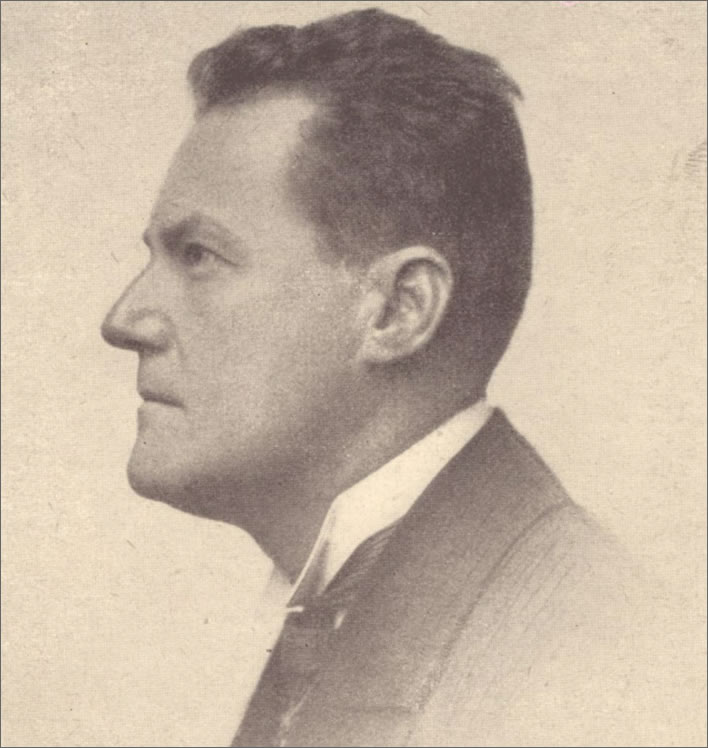

Only five years before Braun's work, in 1912, Rudolf Hans Bartsch (1873-1952) had exploited the growing Schubert market with his fantasy novel Schwammerl.

Rudolf Hans Bartsch, c. 1915. Image: ©Bildarchiv der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Wien.

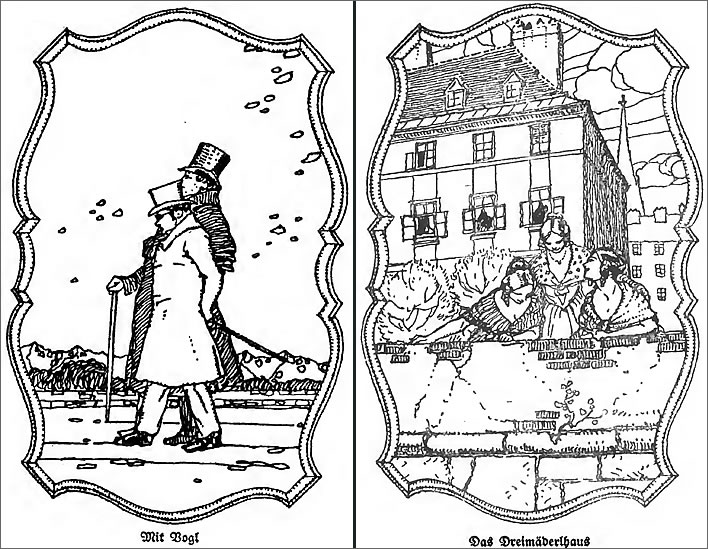

Bartsch's sentimental recreation of Schubert's life was pure kitsch, but very popular kitsch – very, very popular kitsch that sold well for the next thirty years (more than 200,000 copies).

Two illustrations by Alfred Keller from Rudolf Hans Bartsch, Schwammerl / ein Schubert-Roman, Staackmann, Leipzig, 1912.

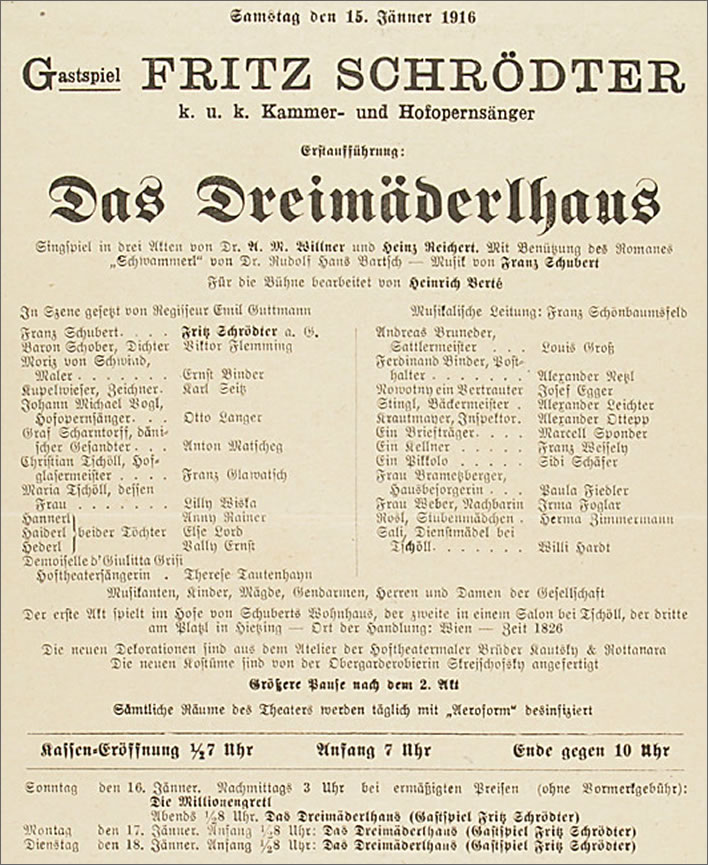

Four years after the appearance of Schwammerl the Austrian composer Heinrich Berté (recte Bettelheim, 1857-1924) reworked bits of Schubert's music into Bartsch's kitsch and came up with the operetta Das Dreimäderlhaus in 1916.

The playbill for the first performance of Das Dreimäderlhaus at the Raimundtheater on 15 January 1916. The noted tenor Fritz Schrödter was engaged to play Schubert, at least for the first performances. Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien.

Franz Glawatsch as Christian Tschöll with his three Mäderl in 'Dreimäderlhaus', 1916. Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien.

Alfred Piccaver as Franz Schubert in Dreimäderlhaus, 1916. Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien.

Two years later Berté's operetta was itself adapted into a silent(!) film of the same name by the Austrian film director and scriptwriter Richard Oswald (recte Ornstein 1880-1963).

Three scenes from the now lost 1918 film of Das Dreimäderlhaus. The only thing we can say with any certainty is that the man at the piano in the top image is Schubert, played by the singer and actor Julius Spielmann (1866–1920). The third still seems to be a death scene, but which of the figures are dying, Schubert, his eyeshadowed love Hannerl or the songbird – or perhaps all three – is uncertain. We learn also that Schubert only possessed one waistcoat (these big budget silent films!). Images: Flickr.

Julius Spielmann, ND. Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien.

Thus, in the six years between 1912 and 1918 Bartsch, Berté, Braun and Oswald had created a Schubert for the masses.

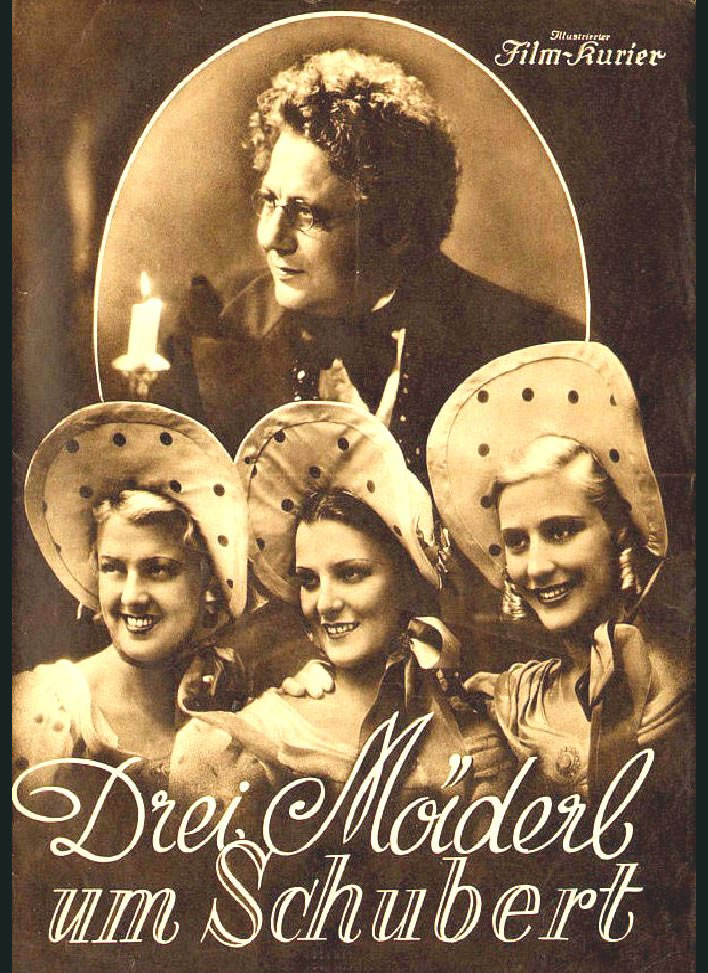

The tradition was continued in 1931 with Schuberts Frühlingstraum (also by Oswald) and in 1936 with a further adaptation of Bartsch's novel, Drei Mäderl um Schubert, which cut its sentimental cloth as required for the politics of the time in the German-speaking world. Then, in 1958, yet another version of the same kitsch, Das Dreimäderlhaus, appeared, just in time to cheer up the masses still shovelling away the rubble of that German dream gone hideously wrong.

A still from the 1931 film, Schuberts Frühlingstraum, another attempt by Richard Oswald to milk the Schubert nostalgia.

An illustration for the 1936 film, Drei Mäderl um Schubert, which recycled Bartsch's material once again.

The man who started all this, Rudolf Bartsch, was no Schubert scholar, merely a patriotic Austrian scribbler. Nor was the man who concocted the 'Circle of Friends', Felix Braun: he was just a jobbing literary type among the hundreds that infested the newspaper feuilletons of the time. He saw his opportunity in the Schwammerl-boom and seized it with both hands.

Rudolf Hans Bartsch, c. 1925. Image: unknown.

That we bring Braun and Bartsch together in the same period and in the same breath is not merely a rhetorical tactic. They were not telepathically connected by the Zeitgeist, the connection was more physical: both men belonged to a now almost forgotten circle of writers based in Sievering, now a suburb in the outer northwest of Vienna, a circle centred on the so-called Dichterhaus, 'Poets' House' in the Agnesgasse 7.

The house was owned by the painter and antiques collector Max von Scherer (1866-1939) and became a salon for a group of local writers. Among them were the two Braun brothers, Felix and Robert, and their sister Käthe. Another painter, the talented Rudolf Bacher (1862-1945) and his close friend Luigi Kasimir (recte Alois Heinrich 1881-1962), also a painter, lived nearby and were frequent participants.

Most interesting for us at the moment is the fact that another close member of the group was Rudolf Hans Bartsch, the author of Schwammerl. He was a particular friend of Luigi Kasimir. Bartsch was indeed a very close member of the group, in fact, since he lodged in the house for several years and, it is said, read some parts of his novel Schwammerl to the assembled guests. Telepathy was not needed. When Braun wrote of the Freundeskreis, Schwammerl was in his mind.

The cluster of artists and scribblers in Sievering were part of a much more extensive network involving such luminaries as Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) and Hugo von Hoffmannsthal (1874-1929), but the reader will be relieved to hear that we shall leave that byway to be explored on another occasion. In later years Kasimir in particular drank deeply of National Socialist ideology; determining how far the sources of that draught reach back into the glorification of the Heimat in the Sievering years is also a task for another day.

Schwammerl stood at the start of the romanticised kitsch that accreted around Schubert's biography. In fact, the fantasy level of Schwammerl is so high that there is little in it that can be counted to be in any way connected with Schubert's 'real' biography as far as we know it.

Nowadays Schubert scholars snigger, roll their eyes and shake their heads pityingly at Schwammerl. The plays and films, based on Bartsch's novel and then on each other, added ever more nonsense to the general understanding of the composer Franz Schubert. But that is, of course, exactly our point.

The tenor Josef Ausim as Franz Schubert in an unspecified production from 1870. Ausim was a singer, actor, comedian and impresario who, in addition to engagements in theatres, made a career of touring with his own one-man shows and operettas. The strange attire and odd upright piano suggest that this photo represents one of his one-man (comedy) turns. Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien.

Schubert's historical reality until the middle of the 19th century was close to non-existent. His biography (despite the work of his first biographers) was almost a blank sheet waiting to be written on, because it was the biography of someone who was merely a cipher, a nobody in his own lifetime and for a long time afterwards. By 1897, the celebrations of the centenary of his birth, the invented biography for this historical nonentity had been written and was just waiting to be decorated by further fantasies.

The Schubert professionals currently shaking their heads in amazement that we should even mention Bartsch's novel and its many spin-offs might care to reflect on the number of people (at least in the first half of the 20th century) who have encountered these products (whether as book or film) with the comparatively miserable circulation figures of their own learnèd products. That nonsense Schwammerl cleared 200,000 copies in steady sales down the decades. Even Felix Braun's slightly more serious work Schubert im Freundeskreis had a published life of more than forty years. By 1954 it had reached a total of 48,000 copies.

Circles in the mind

But one bit of that nonsense is still in circulation even among Schubert scholars: the Freundeskreise – now usually encountered in the plural.

The term suggests that the gifted composer, whose professional success was limited in his own lifetime and limited for decades after his death, at least enjoyed a friendly social context. The more the term was used, usually completely uncritically, the more real and self-evident it became. Several scholars have dug into these circles of friends and classified and structured them according to the origin of their members, leading to an even greater reification of this biographical phantom.

Yes, mea culpa, we on this website are also guilty of lazily using this misleading shorthand on occasions – it's just too convenient. It has become part of the terminology of the Schubert trade.

In 1999 Ilija Dürhammer produced a doorstop PhD spinoff, Schuberts literarische Heimat, which combed through the associations within the Circles of Friends and produced lists and diagrams connecting everyone with everyone else, mainly with the purpose of showing that these circles were in fact expressions of 'homophilic' tendencies. At least we were spared all discussion of Schwammerl, the little fat mushroom.

Another doorstop of a PhD spinoff arrived in that same year (it was a tough year for eyesight and those of us who like our German syntax simple), Michael Kohlhäufl's Poetisches Vaterland : Dichtung und politisches Denken im Freundeskreis Franz Schuberts, which also leveraged the concept of the Circle [singular] of Friends to construct a pot pourri of rather disparate conclusions.

Our own conclusion, after all this eye-strain and brain-strain, is that the concept of the Circles of Friends is not your analytical friend. In reality the young men of the civil servant classes arrived in Vienna from schools in Linz, Kremsmünster etc. and intermingled with the young men – among them Schubert – from Viennese institutions such as the Akademisches Gymnasium and the Stadtkonvikt.

Franz Schubert was neither magnet nor centre for these people. The loose aggregation of young men followed their individual lights and from time to time a subset of them accreted around one person or the other – but never Schubert. Schubert was never a leader nor a focus, but rather an opportunistic follower.

The firebrand Johann Senn was Schubert's first leader figure, until the abysmal Franz von Schober took over that role after Senn's imprisonment and ejection from Vienna.

Schubert had friends, Harry Goldschmidt himself noted that, but the trouble with the term 'Circles of Friends' is that it suggests to the unquestioning reader that Schubert was at the centre of these circles. As historically the last man standing, Schubert is the only individual left whose later fame can organize and hold these 'circles' of nonentities together.

In fact, at the time, as we have noted, Schubert himself was the nonentity – one among many lesser or greater nonentities in these groupings.

Nowadays we would rely on computer software to generate impressive 'network diagrams' and 'sociograms' which represent the social structure of this population of well-educated and talented young men in terms of various factors. The doctorate is waiting for the drudge who undertakes such an analysis, after which there would be no more talk of 'circles'. We would begin to realise that the patterns of Schubert's friendships were improvisatore, depending on the exigencies of whoever happened to be accessible at any particular time and whatever interest moved him at that moment.

Schubert's friends were getting on with their lives, even Schober, missing in action in Breslau for two years, whose wealth allowed him to lead an indolent life of erratic fancy; Joseph von Spaun was missing for several years; Leopold Kupelwieser also away on his studies at times. The greatest loss to Schubert was without doubt Johann Senn, who had a similar, Schubertian scorn for bourgeois existence and who was as detached from contemporary society as the penniless Schubert was. Penury? – a badge of honour!

What a loss Senn was! After Senn was forced away into exile Schober took Schubert under his wing and made him the dependent handmaid of the bourgeois lifestyle. His talent was harnessed as an entertainer of the aesthetic classes in Vienna. Schubert's reference group change from the broke, ascetic, intellectual revolutionaries – the proudly penniless – to the careerist denizens of the Austrian state, occasionally leavened with some independent minded artists who needed to be permanently on the lookout for sponsors and patrons. No wonder Schubert suffered from bouts of depression in that company.

That class thing

It was an entrapment that Senn, who was scratching out his meagre existence giving private lessons to the sons of the rich, would never have tolerated. Schubert was for long periods squatting in the Schobers' apartment and was borrowing money from Schober right up to his death – that which empowers, also enchains. What would Senn have said about Schober's affectation of the Schubertiaden as a means for embourgeoisement?

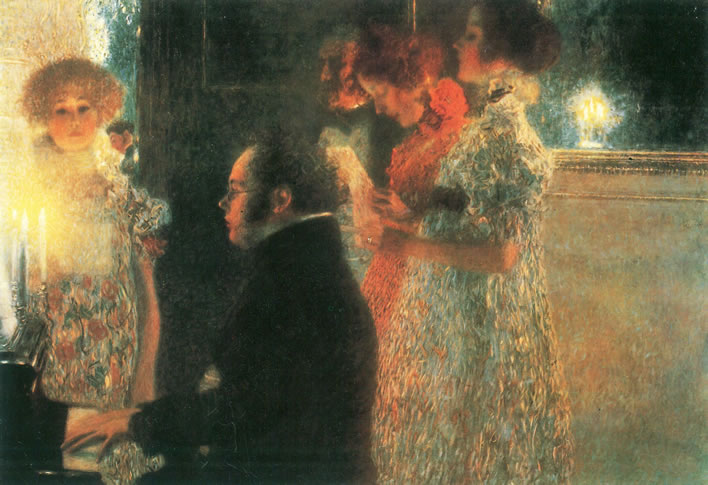

The Schubertiaden became part of the romantic mythmaking of the Schubert biography as much as the Freundeskreise did. Around much the same time as Bartsch, Braun et al. were inventing Schwammerl and his cheerful friends in that mythological country Alt-Wien, 'Old Vienna', the Austrian painter Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) was inventing the glittering candle-lit romance of the Schubertiaden: the slender, blank-faced, dead-eyed girl (Marie Zimmermann, one of Klimt's mistresses); the distinguished-looking older chap lurking in the shadows and, in the foreground but slightly off-centre, the composer, performing for a glass of punch and a sausage roll (not shown).

Gustav Klimt, Schubert am Klavier, 1898 (destroyed 1945)

Readers should put on a pair of Marxist spectacles (preferably the 1848 vintage) and take another look at Klimt's painting. As reality it is nonsense, but as fantasy it is illuminating. What do we see here? The low-status genius at the piano who could never marry; the three women in the expensive frocks who would burst out laughing were someone to hint at romance with the tubby little proletarian with no position, hardly any income and no future; the shadowy figure of feudal Austria in the background. Whether this is what Klimt was trying to say to us is doubtful – but it is what he said to us in effect.

The fact is that Schubert was a marginal figure in the social life of his time. It may well be that, looking back, our modern imaginations make him one of the iconic figures of the age, when, in fact, he was one of the smaller insects in the undergrowth of the Vienna woods. He was marginal in most of the formal and informal cultural groupings and institutions with which he came into contact.

We read of the Schubertiade, but have next to no knowledge of his participation in the many, much more prestigious salons in Vienna – with the 'stiff people', as Schubert liked to call them. The single exception is an anecdote related by Joseph von Spaun in his memoir of Schubert:

When Vogl or Schönstein, accompanied by Schubert, performed songs before larger gatherings they [the singers] were bombarded with applause, but no one took any notice of the modest genius who created the melodies. He was so used to this neglect that it never bothered him at all. Once, when he and Baron Schönstein were invited into a princely residence and were to perform his songs before a very aristocratic audience, the delighted listeners surrounded Baron Schönstein with the most passionate recognition and with praise and compliments on his performance. But when no one bothered to even look at the composer sitting at the piano the noble lady of the house, Princess B. attempted to counter this neglect and greeted Schubert with the most extreme praise, thus implying that he should overlook the fact that the other listeners, completely captivated by the singer, only praised the singer. Schubert thanked her and replied that the Princess should not trouble herself at all about this since he is accustomed to being overlooked and that he even preferred it this way, since he felt less embarrassed.

Wenn Vogl oder Schönstein, akkompagniert von Schubert, in größeren Kreisen Lieder vortrugen und damit hinreißende Wirkungen hervorbrachten, so wurden sie mit Beifall und Dank förmlich bestürmt, aber kein Mensch dachte an den bescheidenen Meister, der die herrlichen Melodien schuf. Er war diese Vernachlässigung so sehr gewöhnt, daß sie ihn nicht im mindesten bekümmerte. Als er mit Baron Schönstein einst in ein fürstliches Haus geladen war, um seine Lieder einem sehr hohen Kreis vorzutragen, umringte der entzückte Kreis den Baron Schönstein mit der feurigsten Anerkennung und mit Glückwünschen über seinen Vortrag. Als aber niemand Miene machte, den am Klavier sitzenden Kompositeur auch nur eines Blickes zu würdigen, suchte die edle Hausfrau Fürstin B. diese Vernachlässigung gut zu machen und begrüßte Schubert mit den größten Lobeserhebungen, dabei andeutend, er möge es übersehen, daß die Zuhörer, ganz hingerissen von dem Sänger, nur diesem huldigten. Schubert dankte und erwiderte, die Fürstin möge sich gar keine Mühe diesfalls mit ihm geben, er sei es ganz gewohnt, übersehen zu werden, ja es sei ihm dieses sogar recht lieb, da er sich dadurch weniger geniert fühle.

Deutsch, Otto Erich. Erinnerungen, p. 157f.

Seen through Joseph von Spaun's feudal eyes, this tale shows the praiseworthy humility of the great genius. But then, feudal aristocrats such as Spaun like their underlings to be humble – it is a very valued quality in an underling.

But if we put on our Marxist spectacles once more we step into a different Weltanschauung, one that sees the social insignificance of the great genius in the feudal context. What the Marxist sees here through those spectacles is not humility but repression. Both Spaun and Schubert are victims of 'false consciousness' in its broadest sense and in its two facets: Spaun's assumption of social dominance and Schubert's assumption of social deference.

The Marxist analyst – still grumbling and bitter as befits the job description – does not let the analysis rest. The princess' condescension (in the meaning that Jane Austen would have used it, sadly now defunct, of 'affability to one's inferiors' [OED]) towards the little commoner was very touching, but ultimately, at least as far as we know, it did him in economic or social terms no good at all – in which case, how does it matter? Affability doesn't pay the rent or buy the scored paper.

Life on the periphery

Schubert drifts in and out of the lives of others. He played a role in the Unsinnsgesellschaft, for example, a grouping which grew up among students of the Kunstakademie, the Vienna Art School in 1817-18. The full extent of his participation has yet to be examined (Rita Steblin has made a start), but he was clearly not the centre of the group. In fact, as Steblin pointed out in puzzlement, there was no codename or entry for Schubert in the list of members of the Nonsense Society, though a number of clear allusions to him in the content. [Steblin, 'New Thoughts on Schubert’s Role in the Unsinnsgesellschaft' in Schubert : Perspektiven, 2010, p. 193.]

The various amorphous 'circles' now identified by Schubert scholarship came into being independently of him. We repeat: to call them his 'Circles of Friends' is misleading, because Schubert was never their centre, but a figure on their respective peripheries with a slight integrative function in his role as tame musician.

It is often noted that Schubert's 'close' friends were pictorial artists or writers, not musicians or composers. His contact with the Unsinnsgesellschaft may have something to do with this, for this was centred largely in the students of the Viennese Kunstakademie. It is also a fair point that until we understand the role the Unsinnsgesellschaft played for two critical years in Schubert's life, we cannot begin to understand the interactions with his other friends and acquaintances during this time, let alone write of 'Circles of Friends'.

Schubertiaden

Schubert was a peripheral figure in so many ways. Even the Schubertiaden, that branding exercise and vanity project undertaken by Franz von Schober, soon took on a form that did not require the attendance of its eponym and ultimately became an event for the purpose of social networking by the denizens of the Austro-Viennese imperial bureaucracy. Schubert and Vogl were an attraction but not a purpose.

Hans Temple (1857-1931), 'Eine Schubertiade bei Ritter von Spaun', c. 1900, heliogravure from a painting. A fine example of the 'artistic licence' (a.k.a. 'derangement') that is so common in Schubert studies, here particularly during the boom years around the turn of the century. Those present at this remarkable event:

Josephine Fröhlich (1803-1878)

Joseph Ritter von Spaun (1788-1865)

Johann Michael Vogl (1768-1840)

Franz Grillparzer (1791-1872)

Eduard von Bauernfeld (1802-1890)

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Leopold Kupelwieser (1796-1862)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Anna Fröhlich (1793-1880)

Katharina Fröhlich (1800-1879)

Johann Mayrhofer (1787-1836)

Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871)

Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien. [Click to view a larger version in a new browser tab.]

Writers of potted and not so potted biographies grasp at the Schubertiaden in an attempt to add some social relevance to his existence. But one or two dozen of the same people having an occasional party during the winter months at which Schubert could play and Vogl could sing for a while before the dancing started – well, that's not social relevance. The events may have given him a bit of hope, a bit of fun, a glass or two of punch and the odd free sausage and, most importantly of all, that balm that soothes away all the afflictions of the creative artist: recognition. But apart from that, the Schubertiaden did nothing for him.

In terms of numbers, this relevance did not extend beyond the quantity of people who could be crammed into a medium-sized Viennese apartment and still leave space for dancing and the buffet table.

In terms of career effect one could argue that in the intervals between the Schubertiaden, their eponym sank back into obscurity and social irrelevance for the attendees. A Schubertiade led to nothing – apart from an invitation to entertain someone else for free.

We recall, too, that Schubertiaden were sometimes held when Schubert himself was unavailable, or when he frankly couldn't be bothered to turn up to participate in his ritualised exploitation as a party entertainer. Ultimately, the main thing was that Vogl or Schönstein appeared, which they would do only if the right names were on the guest list.

And the final thing we must always remember about the Schubertiaden is that no money ever changed hands. Whether you like your Marxist viewpoint hard or soft, these evenings were a brazen exploitation of a creative artist, whether you prefer to see that exploitation as the power of capital exploiting the worker or the aristocrat demanding services from the serf. To rephrase Harry Goldschmidt: Schubert was the grain of corn between the two dialectical millstones of the age: feudalism and capitalism.

There was, of course, friendship, but even that was conditional and sporadic. In the dark days of his syphilis in 1823, with key friends far away – Schober in Breslau, Spaun back in Linz, Kupelwieser in Rome – there were only a few left to buoy him up.

In the serious depression that seems to have fallen upon him in 1827, in his ultimate isolation in that social context, his friends now busy with careers, wives and families, Schubert himself perceives that truth: he was never at the centre of anything. He really doesn't belong here, in the interstices of Alt-Wien.

Writing to Marie Leopoldine Pachler in Graz in autumn 1827 on his return to Vienna from his stay with the Pachlers he confirms his outsider status. This is not the letter of someone who was at the centre of any circles at all:

I haven't adjusted back to Vienna yet, it is big, but lacking in heart, openness, real thoughts and particularly in intellectual deeds. One never really knows whether one is clever or stupid, there is so much muddled chatter here and one seldom or never attains a state of inner happiness.

Wien will mir noch nicht recht in den Kopf, 's ist freylich ein wenig groß, dafür aber ist es leer an Herzlichkeit, Offenheit, an wirklichen Gedanken, an vernünftigen Worten, und besonders an geistreichen Thaten. Man weiß nicht recht, ist man gscheidt oder dumm, so viel wird hier durcheinander geplaudert, und zu einer innigen Fröhlichkeit gelangt man selten oder nie.

[Deutsch, Otto Erich. Schubert: Die Dokumente seines Lebens p 451f Schubert and Frau Pachler, Wien am 27. September 1827.]

When the centre moves, the circle should move with it. Nothing like this can be observed in Schubert's putative 'circles'. Sometimes he is present, sometimes not. Many later commentators remark on his social unpredictability: if he was in the coffee house or the beer house or the Heurigen, he was there, if not, he was not; ditto the Schubertiade, which ultimately did not require his presence at all; ditto the first performance of Ständchen, where the only person not present (at least initially) at the social manifestation of his composition was the composer himself. His nomadic existence in Vienna – seventeen addresses in his life, by Deutsch's count – is not that of a centre of anything. In all social respects he was a peripheral figure, unnoticed by most.

Franz Schubert, postcard image from the boom years, ND. Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien.

His death was scarcely noticed outside his immediate family and friends. He died, almost alone. The first obituary of him in the Wiener Zeitschrift, which appeared shortly after his death, was cobbled together by someone who barely knew him.

He died, was forgotten by most Viennese and remembered by most of his 'friends' as an episode in their young lives – certainly no central figure. For thirty years he was for many just the chap who composed some nice songs, played the piano at parties and died regrettably young. It was the biographers who turned him into one of the central figures of his time – and it was the Schwammerl-fever that consolidated his legacy, however mistakenly.

Franz Schubert, postcard image from the boom years, ND. Image: ©Theatermuseum, Wien.

Resolution

It is a truth which the Schubert business does not like to face, that he was a nonentity until his musical contribution was finally recognized and he was elevated onto the pedestal of his monument. Even his bones were moved around until they found their resting place in the pantheon of the great and the good in Vienna. The Schubert business and the tourism business now likes its new idol and markets him appropriately, with fake images and equally fake biographies as required – Schwammerl was just the start.

Attentive and regular readers of the Schubert pieces on this website may be thinking that we bang on about the theme of Schubert's low socio-economic status too much: we discussed it here and here, to give just a couple of examples from the many we could cite. Well, we bang our busker's drum outside the concert hall with little hope and no conviction that a few of those inside – the frocks! the music! the Winterreise! poor sensitive, repressed gay Schwammerl! – may catch a rumble.

Let's make a resolution for our not-quite-so-shinily-new millennium to look at Schubert and his historical context in a more rational way. A good first step might be to deprecate the misleading term 'Circles of Friends'. 'Friends' is completely accurate and sufficient. Let's also stop writing about Schubertiaden as though they were a good thing for Schubert's career or his mental state. We would then at last be on the way to understanding the life of the tubby little composer in the Strudel of life in Vienna. We have until 19 November 2028 to get it sorted out, ready for the next wave of nonsense that will strike us.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!