Goethe on ice

Richard Law, UTC 2019-06-16 08:22 Updated on UTC 2019-11-13

Our recent piece on Goethe's poem Der Fischer contained an entry from Goethe's diary for 17 January 1778, in which he recorded the tragic death of Christel von Laßberg. He tells us that on that morning he was 'with Duke Carl August on the ice'.

Readers may well have been puzzled by this statement, but there was no opportunity on that occasion to explain it – that lengthy article had already exhausted its quota of byways, digressions and asides.

Let's have another run at it: by 'on the ice' Goethe meant ice-skating – both he and his Duke were enthusiastic and confident skaters.

He learned to skate in the winter of 1771-72 he tells us in his autobiographical work Dichtung und Wahrheit. He had just disentangled himself from Friedrike Brion, the vicar's daughter in rural Sessenheim, to whom he had became semi-betrothed during his two years of legal studies at the University of Strasbourg.

The manner of that dumping was at best heartless, at worst evasively dishonest. When he wrote to Friedrike telling her it was a dumping not just a departure, she responded with a hard-hitting letter to Goethe, now at a safe distance in Mannheim and Frankfurt. This letter has not survived so we do not know its contents. In Dichtung und Wahrheit, though, Goethe recalls that Frederike's letter made unpleasant reading for him:

Friedrike's response to my written farewell tore my heart.

Die Antwort Friedrikens auf einen schriftlichen Abschied zerriß mir das Herz.

[Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, and Walter Hettche. Aus meinem Leben. Dichtung und Wahrheit, 'From my Life. Invention and Truth' (c.1811–1833). Durchges. und bibliogr. erg. Ausg. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2012. Teil 3, Buch 12, p 558. Online Zeno.org.]

In the winter of 1771-72 Goethe got over the broken heart Friederike's letter had caused him. We always have to read Dichtung und Wahrheit with scepticism – better, cynicism – in our hearts, for among the Wahrheit, 'truth', there is much self-serving Dichtung, 'invention'. If we believe Goethe's account, the task of repairing his broken heart turned into yet one more of his self-improvement plans:

Just as injuries and diseases in youth are quickly overcome, because a healthy system of organic life can step in for an unhealthy one and thus give it time also to become healthy again, so physical activities emerged fortuitously, in various favourable opportunities even advantageously, and I pulled myself together, revitalised by many new pleasures and enjoyments.

Horse riding displaced more and more frequently the sauntering, melancholic, tedious and ultimately slow and pointless walks; the goal was reached more quickly, more pleasantly and more comfortably. My younger friends took up fencing again; but with the approach of winter, a new world opened up in front of us, in that I quickly took up ice skating, which I had never tried before and within a short period, thanks to practice, reflection and persistence, I managed to become skilled enough in order to enjoy a happy and crowded ice skating course, without wanting to distinguish myself.

Wie man aber Verletzungen und Krankheiten in der Jugend rasch überwindet, weil ein gesundes System des organischen Lebens für ein krankes einstehen und ihm Zeit lassen kann, auch wieder zu gesunden, so traten körperliche Übungen glücklicherweise, bei mancher günstigen Gelegenheit, gar vorteilhaft hervor, und ich ward zu frischem Ermannen, zu neuen Lebensfreuden und Genüssen vielfältig aufgeregt. Das Reiten verdrängte nach und nach jene schlendernden, melancholischen, beschwerlichen und doch langsamen und zwecklosen Fußwanderungen; man kam schneller, lustiger und bequemer zum Zweck. Die jüngern Gesellen führten das Fechten wieder ein; besonders aber tat sich, bei eintretendem Winter, eine neue Welt vor uns auf, indem ich mich zum Schlittschuhfahren, welches ich nie versucht hatte, rasch entschloß, und es in kurzer Zeit, durch Übung, Nachdenken und Beharrlichkeit, so weit brachte als nötig ist, um eine frohe und belebte Eisbahn mitzugenießen, ohne sich gerade auszeichnen zu wollen.

[Ibid, Teil 3, Buch 12, p 560. Online Zeno.org.]

'Without wanting to distinguish myself' – the progress of Goethe's entire life can be reduced to a desire to distinguish himself in one way or another.

There may be geniuses who are lazy, self-effacing, unfocused and unmotivated, but we never hear of them because their genius is never realized. Goethe's genius, in contrast, is the payload sitting on top of an intercontinental ballistic missile fuelled by ego, aspiration and a deep seated need to prove himself to whoever may be watching.

As a genius he was also intelligently self-aware, meaning that, again and again, we can take the motives he explicitly denies as being implicitly true. His dedicated mastery of ice-skating is therefore typical Goethe, as is the aside that rounds it off, to the effect that he really wasn't trying to show off.

But he gives the game away nearly 200 pages later in Dichtung und Wahrheit, when he recounts a skating incident which took place in Frankfurt in the winter of 1774-75:

A very hard winter had completely covered the Main with ice and turned it into firm ground. The liveliest, unmissable and merriest social activity took place on the ice. Endless skating tracks, wide areas frozen to a glassy surface seethed with crowds on the move.

I was there from early morning, but not warmly dressed and by the time my mother arrived in a carriage to watch the spectacle I was frozen stiff. She sat in the carriage looking imposing in her red velvet coat, closed with thick golden cords with tassels.

'Give me, dear Mother, your coat' I called out spontaneously, without a moment's further thought, 'I'm freezing to death'. She didn't think about it either; in a moment I had the coat on me. It was purple, reached down to my calves, was edged with sable and decorated with gold, all of which, combined with the brown fur hat I was wearing, looked not at all bad.

So I skated up and down and the crowd was so great that no one seemed to take any notice of this peculiar figure. Some did, however, and held it up at a later date half-jokingly, half-seriously, as yet one more of my anomalies.

Ein sehr harter Winter hatte den Main völlig mit Eis bedeckt und in einen festen Boden verwandelt. Der lebhafteste, notwendige und lustig gesellige Verkehr regte sich auf dem Eise. Grenzenlose Schrittschuhbahnen, glattgefrorne weite Stellen wimmelten von bewegter Versammlung. Ich fehlte nicht vom frühen Morgen an und war also, wie späterhin meine Mutter, dem Schauspiel zuzusehen, angefahren kam, als leichtgekleidet wirklich durchgefroren. Sie saß im Wagen in ihrem roten Sammetpelze, der, auf der Brust mit starken goldnen Schnüren und Quasten zusammengehalten, ganz stattlich aussah. »Geben Sie mir, liebe Mutter, Ihren Pelz!« rief ich aus dem Stegreife, ohne mich weiter besonnen zu haben, »mich friert grimmig.« Auch sie bedachte nichts weiter; im Augenblick hatte ich den Pelz an, der, purpurfarb bis an die Waden reichend, mit Zobel verbrämt und mit Gold geschmückt, zu der braunen Pelzmütze, die ich trug, gar nicht übel kleidete. So fuhr ich sorglos auf und ab, auch war das Gedränge so groß, daß man die seltene Erscheinung nicht einmal sonderlich bemerkte, obschon einigermaßen: denn man rechnete mir sie später unter meinen Anomalien im Ernst und Scherze wohl einmal wieder vor.

[Ibid, Teil 3, Buch 12, p 727f. Online Zeno.org.]

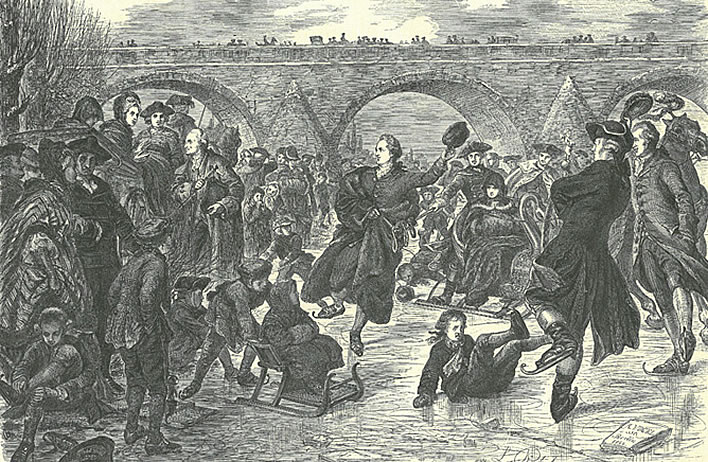

Wilhelm von Kaulbach's spirited re-imagining of the skating episode in Book 16 of Dichtung und Wahrheit. Kaulbach takes poetic licence to its extremes in portraying the tall, dashing Goethe skating effortlessly across the ice under the delighted eyes of his female tribe: his adoring mother, his sister Cornelia (with the snowball) and Maximiliane von La Roche (muse and friend of Goethe's and mother of Bettina von Arnim).

Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874), Der junge Goethe auf dem Eise, 1867. Image: Universität Düsseldorf.

Goethe wrote Dichtung und Wahrheit long after the events it recounts took place. The reader may get the impression that its text comes more or less contemporaneously directly from Goethe's memory, but most of it is carefully constructed from numerous sources. In our accounts of his three crossings of the Gotthard Pass we saw him using this technique to generate his narrative from several texts written by other people.

We are not surprised, therefore, that the present ice-skating anecdote in Dichtung und Wahrheit is actually reconstructed from a letter written to him in 1810 by Bettina von Arnim (née Elisabeth Catharina Ludovica Magdalena Brentano, 1785-1859) the sister of the poet Clemens Brentano (1778-1842) and the wife of Achim von Arnim (1781-1831), both would become renowned as the co-creators of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, the collection of mostly fake 'folk poetry' that marks the beginning of the Romantic Movement in German.

Bettina von Arnim, unknown artist, date unknown. Image: Universität Würzburg.

Bettina had a close friendship with Goethe's mother Catharina Elisabeth Goethe (née Textor 1731-1808) and the two exchanged many letters. Bettina, writing to Goethe in 1810, two years after his mother's death, retails a story that his mother told her about a particular ice-skating incident, which formed the kernel of the story that Goethe tells to us in Dichtung und Wahrheit:

This and the following story made the liveliest impression on me, I can imagine you in both of them, in the full flower of your youth.

Diese und die folgende Geschichte haben mir den lebhaftesten Eindruck gemacht, ich seh Dich in beiden vor mir, in vollem Glanz Deiner Jugend.

[Arnim, Bettina von. Goethe's Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde. Bd. 2. Berlin, 1835, S. 261. 'An Goethe, 28 November'. Online in deutschestextarchiv, also in zeno.org.]

Bettina was not born when this event took place. At the time of her letter she was 25 and Goethe was 61.

On a bright winter's day, when your mother had visitors, you suggested taking them skating on the Main.

'Mother, you have never yet seen me skating and the weather is so beautiful today' etc.

— I put on my crimson coat, which had a long train and which was fastened at the front with golden clasps.

And so we travelled over there, where my son was shooting like an arrow between the other skaters, the cold air had put the roses in his cheeks and the powder flew from his brown hair. When he saw the crimson coat he came up to the coach gave me a friendly laugh

— 'Now, what are you after?', I said. 'Oh, Mother, you are not cold in the carriage, give me your velvet coat',

— 'You are not going to wear it, are you?',

— 'Of course I'm going to wear it.'

— So I took off my magnificent warm coat and he put it on, folded the train over his arm and then skated off, like a son of the gods, across the ice. Bettina, if only you had seen him!!

— There will be nothing so beautiful ever again, I clapped my hands with pleasure!

I'll remember as long as I live how he skated out through one arch of the bridge and back through the other and how the wind drew out the train behind him, on that occasion your mother was with you on the ice and you wanted to please her.

An einem hellen Wintertag, an dem Deine Mutter Gäste hatte, machtest Du ihr den Vorschlag, mit den Fremden an den Main zu fahren. »Mutter, Sie hat mich ja doch noch nicht Schlittschuhe laufen sehen, und das Wetter ist heut so schön« usw. – Ich zog meinen karmoisinroten Pelz an, der einen langen Schlepp hatte und vorn herunter mit goldnen Spangen zugemacht war, und so fahren wir denn hinaus, da schleift mein Sohn herum wie ein Pfeil zwischen den andern durch, die Luft hatte ihm die Backen rot gemacht, und der Puder war aus seinen braunen Haaren geflogen, wie er nun den karmoisinroten Pelz sieht, kommt er herbei an die Kutsche und lacht mich ganz freundlich an, – »nun, was willst du?« sag ich. »Ei Mutter, Sie hat ja doch nicht kalt im Wagen, geb Sie mir Ihren Sammetrock«, – »du wirst ihn doch nicht gar anziehen wollen«, – »freilich will ich ihn anziehen.« – Ich zieh halt meinen prächtig warmen Rock aus, er zieht ihn an, schlägt die Schleppe über den Arm, und da fährt er hin, wie ein Göttersohn auf dem Eis; Bettine, wenn du ihn gesehen hättest!! – So was Schönes gibt's nicht mehr, ich klatschte in die Hände vor Lust! Mein Lebtag seh ich noch, wie er den einen Brückenbogen hinaus und den andern wieder herein lief, und wie da der Wind ihm den Schlepp lang hinten nachtrug, damals war Deine Mutter mit auf dem Eis, der wollte er gefallen.

[Ibid.]

Ludwig Pietsch's recreation of the skating incident in Frankfurt, which follows both Goethe's and Bettina's accounts much more closely than Kaulbach's picture. Here Goethe is recognisably Goethe and not the god Apollo with curly locks; the ladies in the party remain in the carriage (on the left); Goethe is shown prominently holding the train of his mother's coat, a feature which was only contained in Bettina's letter. The detailed representation of the Alte Mainbrücke (now long gone), with its rounded arches and prominent buttresses also relate well to Bettina's account, compared with Kaulbach's vague background hint at the presence of the bridge.

Ludwig Pietsch (1824-1911), Goethe auf dem Eise in Frankfurt a.M. Original drawing. Woodcut appeared in the Illustrirte Zeitung, Goethe-Nummer, 24. August 1899, S. 245. Image:

As we have seen, Goethe dated this incident as occurring in the winter of 1774-75, shortly before he moved to Weimar and the employ of Duke Carl August. The only hint that the story came from an external source is the otherwise cryptic remark in Dichtung und Wahrheit about the people who took the skating incident as being one of his 'anomalies'.

It is telling that he leaves out any mention of the things which modern, psychologically interested readers find most compelling in the tale: his need to show off to his mother and the joy his mother took at seeing her son cruising effortlessly over the ice. Perhaps Kaulbach merely drew what Goethe's mother saw. A psychiatric assessment of Goethe? Now that really would be a digression!

Catharina Elisabeth Goethe (1731-1808), c.1785-1790, unknown artist. Image: Source unknown.

In Weimar, from 1775 onwards, he found himself amongst skating fanatics, at the head of whom was Duke Carl August himself. The winters of the time were frequently very cold and during them the court took every opportunity to amuse itself on ice and in snow.

Baron Karl Wilhelm Heinrich von Lyncker (1767-1843), then a page at the court, whom we met in the previous article, provides the standard account of the life on ice of the court in Weimar:

Ice skating was a custom from the earliest years of the Duke's reign [1775] and became a regular courtly amusement. The Captain of Horse von Lichtenberg, who began his career in Dutch then in Prussian service, was a master of this art. Goethe, who had learned to skate in his native city, also enjoyed it a lot.

The pond in the Baumgarten, which then still belonged to the court, but which later on was bought by the legation councillor Bertuch, was used for this pastime. A cottage was erected and all the local worthies were allowed to use it.

The Duke himself skated almost daily for a while; the Duchess regent, Frau von Stein and several others also learned to skate and it was a pleasure to watch the serene lady floating over the ice with complete propriety. [The actress and singer] Corona Schröter had become quite skilled at skating and her beautiful figure looked splendid.

Several breakfasts were given there by the court and by other nobles. When later the Schwansee ['Swan Lake'] meadows were flooded the Duke organized larger parties, even ice masquerades and illuminations, attended by the most serene ladies and nobility.

Das Schlittschuhfahren war schon in den ersten Regierungsjahren des Herzogs Sitte und zu einer fortlaufenden Hofvergnügung geworden. Der Rittmeister von Lichtenberg, früher in holländischen, dann in preußischen Diensten, war Meister in dieser Kunst. Goethe, der es in seiner Vaterstadt erlernt hatte, fand auch viel Gefallen daran. Den Teich im Baumgarten, welcher damals noch der Herrschaft gehörte, späterhin aber von dem Legationsrath Bertuch erkauft wurde, benutzte man zu dieser Lust; ein Häuschen wurde darauf errichtet und allen Honoratioren der Zutritt gewährt. Der Herzog selbst fuhr eine Zeit lang fast täglich; auch die regierende Herzogin, die Frau von Stein und mehrere andere Damen erlernten es, und es war eine Freude die Durchlauchtige Frau mit vollem Anstand über das Eis schweben zu sehen. Die Corona Schröter hatte viel Fertigkeit darin erlangt; ihre schöne Figur nahm sich dabei vortrefflich aus. Mancherlei Frühstücke wurden dabei teils von den Herrschaften, teils von Andern von Stande gegeben. Als aber späterhin die Schwanseewiesen überschwemmt wurden, gab der Herzog dort größere Feste, sogar Eis-Maskeraden und Illuminationen, denen die durchlauchtigsten Damen und der Adel beiwohnten.

[Karl Freiherr von Lyncker, Am Weimarischen Hofe unter Amalien und Carl August, Berlin, 1912, p. 80-82. Online.]

Friedrich Preller the Elder (1804-1878), Eisfahrt auf den Schwanseewiesen Weimar, 1824. Image: Schloss Weimar.

We page boys usually appeared only twice a week, in order not to affect our schooling too much and the Duke, as well as Goethe, had us learn skating tricks.

For example, we had to stab apples with daggers whilst skating past, jump over poles, chase hares with riding crops, sometimes blanks were shot from pistols behind the fleeing game, which for us was a great excitement.

During a night-time masquerade and illumination we were given devil masks and had to drive the ladies who could not skate around in sleighs between the lighted up pyramids and fiery rockets and firecrackers. There were also fireworks fixed on the horns of our devil caps which the men who skated past ignited with burning fuses, keeping a continuous display going.

Since we frequently fell and damaged ourselves somewhat, our parents were not always happy with these amusements. All such things were blamed on Goethe and most of the events of that time were spoken about with mixed feelings.

Wir Knaben erschienen gewöhnlich nur zwei Mal die Woche, um unsere Lehrstunden nicht zu sehr zu vernachlässigen, und der Herzog, so wie Goethe, ließen uns Kunststücke erlernen. Wir mußten nämlich in vollem Schlittschuh-Fahren Äpfel mit bloßen Degenspitzen aufspießen, über Stangen springen, wurden gleich Hasen mit Parforcepeitschen gehetzt, ja man schoß aus nur mit Pulver geladenen Pistolen hinter dem flüchtigen Wilde drein, welches für uns die größte Lust war. Bei einer nächtlichen Maskerade und Illumination erhielten wir Teufelsmasken und mußten die Damen, welche nicht selbst Schlittschuh fuhren, auf dem Schlitten zwischen den erleuchteten Pyramiden und feuerspeienden Raketen und Schwärmern herumkutschieren. Auf unsern mit Teufelshörnern versehenen Mützen waren gleichfalls Schwärmer angebracht, welche die vorbeifahrenden Herrn mit brennenden Lunten anzündeten und somit ein fortlaufendes Feuer bewirkten. Da wir aber oft auf das Eis fielen und uns mit unter leicht beschädigten, so wollten unsere Eltern diese Belustigungen nicht immer gut heißen. Alle dergleichen Dinge gab man hauptsächlich Goethen Schuld, und gewöhnlich wurde über die meisten Vorgänge damaliger Zeit etwas zweideutig gesprochen.

[Ibid.]

Come to think of it, perhaps Goethe's skating hobby should have been discussed in the previous article after all. In the context of that diary entry giving Goethe's morning skating activities with his duke it is not as much of a digression as one might imagine.

In the general context of Goethe's depression, presumably including his forced role in the vacuity of court life, amusing himself and his duke with his show-off antics on the ice whilst his servants were searching for the missing Christel von Laßberg must have come back to haunt him when the body of the 'wet woman' was finally found in the cold weir under the Floßbrücke.

That feeling of guilt would have been yet one more reason for the frantic distraction therapy that followed, just as learning to skate had been the distraction therapy for his guilt over his brutal abandonment of Friedrike Brion a few years before. But then in Frankfurt, as now in Weimar, he got over it.

Update 13.11.2019

In his 1887 work Imaginary Portraits, the essayist, literary and art critic Walter Pater (1839-1894) made use of the account of Goethe's skating episode:

The Enlightening, the Aufklärung, according to the aspiration of Duke Carl, was effected by other hands; Lessing and Herder, brilliant precursors of the age of genius which centered in Goethe, coming well within the natural limits of Carl's lifetime. As precursors Goethe gratefully recognised them, and understood that there had been a thousand others, looking forward to a new era in German literature with the desire which is in some sort a "forecast of capacity," awakening each other to the permanent reality of a poetic ideal in human life, slowly forming that public consciousness to which Goethe actually addressed himself. It is their aspirations I have tried to embody in the portrait of Carl.

A hard winter had covered the Main with a firm footing of ice. The liveliest social intercourse was quickened thereon. I was unfailing from early morning onwards; and, being lightly clad, found myself, when my mother drove up later [153] to look on, fairly frozen. My mother sat in the carriage, quite stately in her furred cloak of red velvet, fastened on the breast with thick gold cord and tassels.

'Dear mother,' I said, on the spur of the moment, 'give me your furs, I am frozen.'

She was equally ready. In a moment I had on the cloak. Falling below the knee, with its rich trimming of sables, and enriched with gold, it became me excellently. So clad I made my way up and down with a cheerful heart.

That was Goethe, perhaps fifty years later. His mother also related the incident to Bettina Brentano: —

There, skated my son, like an arrow among the groups. Away he went over the ice like a son of the gods. Anything so beautiful is not to be seen now. I clapped my hands for joy. Never shall I forget him as he darted out from one arch of the bridge, and in again under the other, the wind carrying the train behind him as he flew.

In that amiable figure I seem to see the fulfilment of the Resurgam on Carl's empty coffin — the aspiring soul of Carl himself, in freedom and effective, at last.

Walter Pater, Imaginary Portraits, 'Duke Carl of Rosenmold', Macmillan, London 1887, p. 178-180. Online at Gutenberg.org.

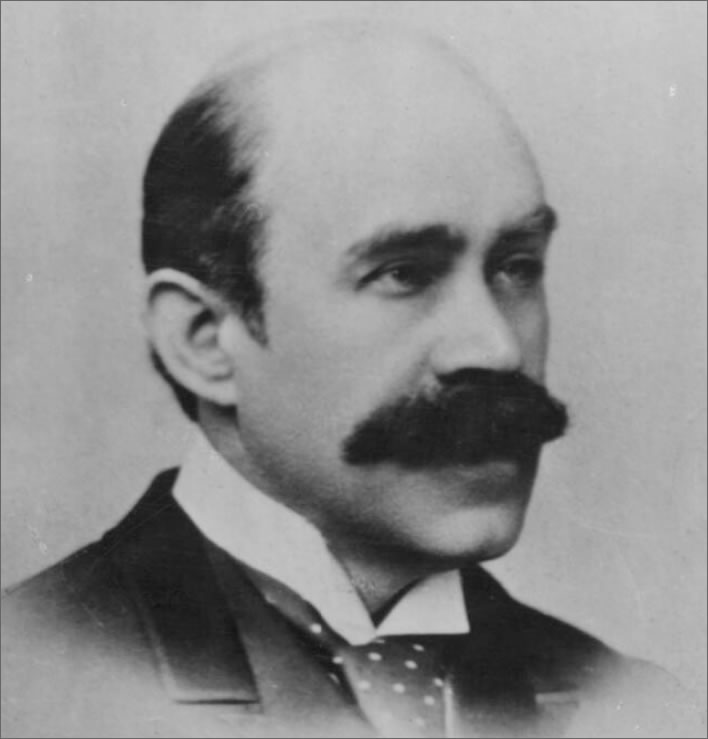

Walter Horatio Pater, by Elliott & Fry, half-plate glass copy negative, 1890s, NPG x81864 Image: National Portrait Gallery UK.

Readers who are curious about the (fictional) 'Duke Carl', who embodies the equally fictional 'public consciousness' to which Goethe fictionally 'addressed himself' must plug through the eight thousand or so words of Pater's concocted 'imaginary portrait', 'Duke Carl of Rosenmold'.

With the publication a few years ago of a new critical edition of Walter Pater's Imaginary Portraits it might have been expected that Pater's work would have experienced a revival. But it has not happened – Pater's culture has gone for ever, the once much admired stylist in English prose now seems fustian, prolix, his sentences mannered rather than stylish.

Reading him now is akin to sniffing your departed Granny's favourite shawl: musty, threadbare and with a whiff of old violets. Reading his etiolated, back-to-front syntax has become harder as our age has progressed. Our modern concept of literary style is increasingly formed by the laconic social media message, that is: the shorter the better.

Our age of fakery also worries about authenticity. We can still accept that 'historical novels' move imagined figures around a more or less well researched historical stage – there the story is the thing – and these fictions bring their times to life. But the figures of Pater's portraits have a heavy load to bear, in that they have to embody not just the age in which they live, but some great cultural transition which is taking place at that time.

The word Zeitgeist springs to mind, a word which Pater seemingly chose not to use. Unlike Hornblower et al., who have personalities to which we can relate and which help us to suspend disbelief in their existence, the figures in Pater's portraits are anodyne, bloodless symbols.

No reader would ever for a second think that such ciphers as 'Duke Carl' had ever lived. Worse: no reader who knows a bit about Goethe is happy with a name that recalls Goethe's patron, Duke Carl August, nor with the fictional Duke Carl's role as a kind of Doppelgänger of Goethe in his travels to the Gotthard and who also stands at the 'apex' towards which 'the whole of Europe sloped upwards'. Is this Pater, or Duke Carl August or Duke Carl or Wolfgang? The book is therefore hopelessly mistitled, for these are not in any arguable sense 'portraits' – just a patchwork of the concocted and historical allusions in the service of some cultural thesis.

Pater is generally held to be one of the intellectual fathers of that late 19th-century gaggle of bloodless, effete, usually degenerate and usually drunk writers (with the one exception of Oscar Wilde).

Ironically, by the time that Pater was writing his portraits, the age of Goethe had long passed. Goethe had died seven years before Pater was born. Goethe's work was a magnificent, still feudal, establishment monolith, but had fossilised, whilst the new German culture moved through the second half of the 19th century.

German writers from Heine onwards had left Goethe's world behind well before the 1848 revolution in Europe had opened an age in which everything would change and do so with a rapidity never before known to man.

It is telling that the young Pater did not attach himself to the cause of his contemporaries, the young artists of the great movements in German literature which followed the Goethe era, but chose to stick in the company of the previous generation, all of them yesterday's men: Goethe and the other three 'stars' of Weimar, Schiller, Lessing and Herder. Pater was out of date even before he went out of date.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!