13 December Saint Lucy's Day

Richard Law, UTC 2019-12-10 09:12

Over the last few years on this website we have attempted to lighten the early December mood with a piece for Saint Lucy's Day, the 13th of the month. This year we take as our subject the saint herself. We do this as atheist-agnostics, without any axe to grind for organized religion.

The person we call Saint Lucy may have existed; she may have been called 'Lucia' or some variant; she may have lived in Syracuse, the ancient city near the southern extremity of Sicily; she may have lived in the era of Diocletian (244-305 AD) and particularly during that emperor's persecution of all things Christian, which was quite unparalleled in its ferocity; she may even have been born in 283 and have met her end in 304.

But even for this most rudimentary indication of 'existence', for any of the 'facts' above, we have not the slightest scrap of documentary evidence. Nothing.

Who was Lucy? What was she?

There once was a man called Voltaire. We shrinking band of adherents read that second paragraph and assign poor old Lucy to our tooth fairy category – not a single statement of that paragraph can be considered to be demonstrably 'true' in any accepted sense of that word.

Apart from one sense, that is. It is 'true' insofar as the reader wants it to be 'true' – a particularly egregious violation of reason that seems to have become intellectually respectable these days.

The Christian Church wanted Lucy to exist. Down the long centuries its acolytes did what they could to achieve this goal, just as they did with so many of the early saints and martyrs, Saint Barbara, for example. Christianity built an heroic founding myth out of them, the ones who stood firm in their faith during the three centuries of persecution in the Roman Empire that reached its peak in the barbarities of Diocletian.

The end of that era of persecution was astonishingly abrupt, lasting no more than a handful of years. It was the Emperor Constantine (272-337) who brought about that end. Under his reign Christianity came to be tolerated, then recognized, then institutionalised.

The narrative of Lucy's hagiography expanded slowly with the expansion of Christianity. More than a century after her presumed death an inscription mentioning her name was 'found' in the catacomb of San Giovanni in Syracuse. It may very well be that a local Christian of this name was martyred around this time and that her death passed into the local folklore – we can no more rule this out than we can rule it in. Nevertheless, this evanescent hero is really too frail to bear the weight of the legends that would be heaped upon her by subsequent ages, although she rapidly became a significant figure.

The very earliest form of the Roman Canon, the eucharistic prayer at the communion climax of the Catholic mass, in use even by the early Fathers of the Church, mentions Lucy. She is named in a section praying to the apostles, saints and martyrs, Nobis quoque peccatoribus, which is held to have been added to the Canon towards the end of the fifth century, around a century before Saint Gregory instituted the relatively definitive version of the Canon as part of the Mass. In this section Lucy is listed among the seven female martyrs and saints, Felicitas, Perpetua, Agatha, Lucy, Agnes, Cecilia and Anastasia.

It is fair to point out, though, that we are now nearly three centuries further on from the alleged moment of her alleged martyrdom – three long centuries of chaos and upheaval; three long centuries of creative hagiography.

It is also fair to point out that although we empiricist fanatics have been so rude about Lucy's physical existence – or rather the lack of it – nearly two millennia of reverence and veneration have made her a greater reality than a mere documentary existence alone could have ever done. There are probably thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands of people around the world who address their sincere prayers to her every day.

The early Lucy

When was Lucy made a saint? No idea. Lucy was canonized by that mysterious process of veneration that applied to all the early saints. The theory is that, beginning with local veneration, a figure, usually a martyr, would gradually emerge into the consciousness of the Christian community as particularly respected or reverenced. At some point a bishop would make this veneration official and then time and custom would work their magic.

The process is organic and highly obscure, particularly in comparison with the formal and bureaucratic procedure applied by the Church of Rome since the late 16th century. That so many famous saints of its early history are, like Lucy, lacking all evidence for their actual historical existence is an embarrassment with which the Church's modern rationalists have to live. The power of the continued existence of these obscure figures in the hearts and minds of the faithful is self-propagating, though.

Another three or perhaps four centuries after her presumed death, some early Christian martyrologies – for which we have no secure dates either – mention her and give hints at her life and her death. Consider that: after four hundred years of imperial collapse, invasions and turmoil, suddenly someone somewhere writes something down about this Lucia of Syracuse.

Finding Lucy

There seems to have been some Christian folk memory that was trying to reach back across those centuries to a time when Christianity was almost wiped out, trying to recover its early heroes in fragmentary holograms from that dreadful past. Since nothing was really known about Lucy, then just making something up had to do – a noble lie, in other words, assisted by the Chinese whispers of oral history down a dozen generations.

The culture of the West had to make do with noble lies, Chinese whispers and concocted histories until the middle of the 18th century, when scientific empiricism and the rationalism of the Enlightenment finally set new evidential standards for fact. Until that moment men and women lived in a fog of hopes, beliefs, wishful thinking and superstition. More than two and a half centuries later, in our social media age, one might argue that there is a lot of that fog still hanging around.

Once Christianity had triumphed in the West, the stories in the martyrologies were decorated progressively with all kinds of marvels and miracles. But legends were not enough: the lives of the saints and martyrs of the early Christian Church, lacking all documentary foundations, were also frequently supported by the existence of physical 'relics'.

The fact that the provenance of these bits and bobs was as fanciful as the legends they were supposed to support was no hindrance to their widespread adoption. Even in today's supposedly rationalist, science-centred world, there are thousands of churches around the world with caskets and cases containing the remnants of someone or other and millions – perhaps billions – of people who venerate these objects.

We rationalists shake our heads in amazement, but attempt to remain cheerful, tranquil, polite even: 'Another chocolate biscuit, Father?'

Follow the relics

Some bones alleged to be those of Lucy turned up in Constantinople in the middle of the eleventh century. These remains seem to have stayed in Syracuse for seven centuries, without attracting any attention of which we have any record.

During those seven centuries those relics even survived the more than two century long Muslim occupation of Syracuse. That was not a good time to be a Christian in Syracuse: a large number of inhabitants were massacred and the cathedral was turned into a mosque. Somehow, however, 'Lucy's bones' survived.

In 1038, the Byzantine general Georgios Maniakes freed Syracuse from the Muslim Caliphate. Shortly thereafter, so the story goes, he brought the putative remains of Lucy back to Constantinople. After that, all traces of them fade.

One and a half centuries later, in 1204, it was the turn of Constantinople to fall, not to the Turkish hordes but to a gang of 'crusaders', fellow Christians from France and Venice, led by the 96-year-old Venetian Doge, Enrico Dandolo. Enrico's vigour, violent energy and tactical cunning put us weary septuagenarian striplings to shame.

The collapse of Constantinople took place during the Fourth Crusade, one of the crusades that gave crusading a bad name. This crusade was initially supposed to conquer Egypt for Christendom, but turned into a power play that sacked the Christian Constantinople instead. The correct word to describe the events leading up to the sacking, complex beyond our scope, is, of course, 'Byzantine'. It is an indisputable fact that in the long centuries since Christianity got a footing, the greatest danger for Christians has generally come from other Christians.

In Constantinople in April 1204 there began a three-day orgy of murder, fire-raising, destruction and plundering by the crusaders. The extent of the cultural loss in that last repository of the Classical and early Christian worlds during those three days of mayhem is simply unimaginable.

Steven Runciman, the doyen of English crusade specialists, assigned the Fourth Crusade to a section of his opus magnum he urbanely titled 'Misguided Crusades', but delivered an impressive description of the events of the sacking of Constantinople.

There was a little fighting in the streets as the invaders forced their way through the city. By next morning the Doge and the leading Crusaders were established in the Great Palace, and their soldiers were told that they might spend the next three days in pillage.

The sack of Constantinople is unparalleled in history. For nine centuries the great city had been the capital of Christian civilization. It was filled with works of art that had survived from ancient Greece and with the masterpieces of its own exquisite craftsmen. The Venetians indeed knew the value of such things. Wherever they could they seized treasures and carried them off to adorn the squares and churches and palaces of their town. But the Frenchmen and Flemings were filled with a lust for destruction. They rushed in a howling mob down the streets and through the houses, snatching up everything that glittered and destroying whatever they could not carry, pausing only to murder or to rape, or to break open the wine-cellars for their refreshment. Neither monasteries nor churches nor libraries were spared. In St Sophia itself drunken soldiers could be seen tearing down the silken hangings and pulling the great silver iconostasis to pieces, while sacred books and icons were trampled under foot. While they drank merrily from the altar-vessels a prostitute set herself on the Patriarch’s throne and began to sing a ribald French song. Nuns were ravished in their convents. Palaces and hovels alike were entered and wrecked. Wounded women and children lay dying in the streets. For three days the ghastly scenes of pillage and bloodshed continued, till the huge and beautiful city was a shambles. Even the Saracens would have been more merciful, cried the historian Nicetas, and with truth.

At last the Latin leaders realized that so much destruction was to nobody’s advantage. When the soldiers were exhausted by their licence, order was restored. Anyone who had stolen a precious object was forced to give it up to the Frankish nobles; and unfortunate citizens were tortured to make them reveal the goods that they had contrived to hide. Even after so much had wantonly perished, the amount of booty was staggering. No one, wrote Villehardouin, could possibly count the gold and silver, the plate and the jewels, the samite and silks and garments of fur, vair, silver-grey and ermine; and he added, on his own learned authority, that never since the world was created had so much been taken in a city. It was all divided according to the treaty; three-eighths went to the Crusaders, three-eighths to the Venetians, and a quarter was reserved for the future Emperor.

Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, Volume III, The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades, Cambridge University Press, 1955, p123-4.

Yet amongst all the destruction and loss, Enrico Dandolo supposedly caused 'Saint Lucy's relics' to be taken to Venice. This is particularly odd, since amongst the mad lust for booty so many other religious relics, buildings and artefacts were destroyed utterly. The crusaders were principally French knights and Venetian sailors, a fact which makes us even more suspicious of this sudden burst of reverence for the girl from Syracuse. It seems likely that the Doge of Venice, surrounded by the smoking ruins of Christianity in the east, saw a fine opportunity for the acquisition of a reputational treasure for his city, but… who knows?

In short, we latter-day followers of the Sage of Ferney find as little empirical evidence in this tale as we did in the supposed historical 'facts' of Lucy's life – only puzzling questions. Yet more tooth fairy, in other words.

The acquisition of the relics had hardly been a saintly act, but, once in Venice, all was forgiven. The bones went first to the island of San Giorgio Maggiore. Then, 75 years later in 1279, they were transferred to the Church of Cannaregio, which was then rededicated to her as the Church of Santa Lucia, where they remained for nearly six centuries. In 1860 they were transferred to the nearby San Geremia church, now known as the Santuario di Lucia.

In modern times the Venetian tourist industry has marketed her as loudly as it would any other commodity. For visitors there is no escape from Santa Lucia this and Santa Lucia that. Enrico Dandolo would be proud of his foresight in securing those bones for his city.

_Santa_Lucia_01_708x604.jpg)

The relics of Saint Lucy in the Santuario di Lucia (San Geremia) in Venice – a fine piece of understatement. Image: ©Didier Descouens. [Click to open a larger version in a new browser tab].

The propaganda technique in all this historicity, though easy to spot, is still seductive and has seduced those who wish to be seduced down the ages: take a washing line of historical events and hang on it at various intervals some imagined Lucy event.

Readers who think we are being overly harsh in our scepticism and whose hearts were perhaps softened by all this decorative prose about the recovery of Syracuse and the doings of the Fourth Crusade should note that an equally (im)probable and competitive scenario exists.

According to this account, her relics turned up in the central Italian town of Corfinio whence they were transported to Metz around 970. They remained in Metz during the following centuries, even surviving – just – the anti-religious rigours of the French Revolution. They are still there. The relics in Metz have almost as many supporters among the locals as those in Venice – one analysis found evidence of burning on the bones, so take that, Venice! In other words, just as in the case of Saint Barbara, one has to choose one's relics and one's fairy story with care.

If, against all scepticism, these Venetian bones are those of the person now called Saint Lucy, they can hardly be considered to be at peace. A forefinger and an arm are now in Syracuse, as a gesture to the Sicilians. In 1955 the skull – a less than cheerful sight – was covered with a silver face mask.

Saint Lucy behind bulletproof glass and a silver mask in the Santuario di Lucia (San Geremia) in Venice. Image: ©Didier Descouens

Worst of all, on the night of 7 November 1981 two robbers armed with guns entered the Santuario di Lucia, smashed open the vessel containing Lucy's relics and made off with the bones wrapped up in her gown, inexplicably leaving the skull behind.

This is an Italian tale, so no one knows even today what really went on behind the scenes. The thieves are supposed to have demanded a ransom – 'pay up or the bones get it' – some say of 200 million lire, some say 40 million, but the general public outrage at the crime seems to have got to the criminals in the end, who abandoned their plan (most likely when the Mammas found out what their boys had done).

After being missing for 36 days, the relics were 'found' on the tiny uninhabited island of Montiron in the lagoon, wrapped in a white sheet, just in time – remarkably so – for their return to be announced on the morning of Saint Lucy's Day, 13 December. Two young men were arrested and imprisoned in short order, but had to be released after a few months in prison in May of 1982 for lack of that plaything of the Enlightenment, evidence. Lucy is now resting under an armoured glass box.

Follow the tale

By the late Middle Ages the cult of Saint Lucy had expanded enormously. The arguably most influential account of her life was to be found in what became known as the Legenda Aurea, 'The Golden Legend or Lives of the Saints', written by Jacobus de Voragine (c.1230-1298), a Dominican Friar from the region of Genoa. In 1292 he became Archbishop of Genoa.

It is thought that he wrote the present work around 1260, fifty or so years after the sacking of Constantinople and around nineteen years before the transfer of 'Lucy's bones' to their long-term resting place in the Church of Cannaregio, which was then renamed as the Church of Santa Lucia. Around 700 years after his death he was beatified by the Catholic Church (in 1816). A modern translator of the work, Father William Granger Ryan, notes

The popularity of the Legend was such that some one thousand manuscripts have survived, and, with the advent of printing in the 1450s, editions both in the original Latin and in every Western European language multiplied into the hundreds. It has been said that in the late Middle Ages the only book more widely read was the Bible.

Jacobus de Voragine, William Granger Ryan (translator), The Golden Legend, Volume I: Readings on the Saints, Princeton University Press, 1993. Introduction, p. xiii.

An indication of the quantity of manuscripts still in circulation is given by the fact that in 2008 a late 14th century specimen on vellum 'only' raised a sale price at auction of 9,375 GBP, still 50% better than the top estimate, though. As a return on 289 pages of painstaking calligraphy and illustration, it seems to have been barely worth the scribe's interrupting his observances.

Paradoxically, Jacobus' astonishing success with his Legenda Aurea has had fateful consequences for scholarship. In addition to having around a thousand manuscripts to compare, each compiler/author has treated Jacobus' original as merely a starting point for further compilations. Before even attending to the text itself, the scholar is faced with the problem of deciding which tales come from Jacobus and which from others. Fortunately, for our present purposes we don't have to disentangle such skeins.

The Legenda Aurea is only one of many hagiographies circulating in this period. As is the way with these things, every writer took the opportunity to add their own bit of gruesomeness to our Lucy's martyrdom: boiling oil, seething pitch, gouged out eyes. Although Jacobus doesn't mention the gouging out of her eyes, the theme was frequently associated with her and became a common part of her iconography: the saint daintily holding a dish containing her eyeballs. The Middle Ages were a fun time to be alive, it seems, before CGI animation took all the pleasure out of torture and mutilation.

But isn't the very existence of so many contradictory elements – such an abundance of morbid creativity arising essentially out of nothing – one of the main reasons why we sceptics purse our lips and wrinkle our brows?

The legend in words and pictures

The vivid and pictorial details which made Jacobus' work a bestseller have been a source of inspiration for religious artists down the pious ages. The pictorial representation of the martyrdom of Saint Lucy we present here was done as an altar panel by the painter we only know as the 'Master of the Figdor Deposition' in Haarlem in the Netherlands sometime between 1505 and 1510, let's say around forty years after Legenda Aurea was first published. There can scarcely be any doubt that the unknown artist took de Voragine's work as his source.

In effect, the artist created what we would now call a comic-book page, only without the frames around the individual scenes. Instead of using frames, the artist has embedded a series of asynchronous events from the hagiography into a synchronous representation of a late Medieval landscape. Here it is:

The Master of the Figdor Deposition, The Martyrdom of St Lucy, Haarlem, c.1505-1510. Image: Rijksmuseum [Click on the image to display a larger version in a new browser tab].

There is much to be said about the iconography of this painting – the figures, their clothes, the buildings and the landscape – but this is beyond our competence. Let's just use the painting as a visual guide whilst we follow Father Jacobus' account of the Lucy's life and martyrdom.

The account is longwinded and written in a style that is quite unsuitable for the social media age. Jacobus not only embellished the tale with detail, he reproduced much of it in the form of direct speech between the participants. The use of direct speech adds life to the story and adds a veneer of seeming authenticity to it, but slows down the narrative appreciably.

William Caxton's (c.1422-c.1491) 1483 English translation has some antique charm in places, but is heavy going for moderns. We have used here Father William Granger Ryan's 1993 translation of Jacobus' Latin.

A name to conjure with

Jacobus opens with a riff on Lucy's name as cognate with Latin lux, 'light' (genitive 'of light': luce). There can be hardly a doubt that such etymological reasoning has been a particular motivation for the veneration of Saint Lucy down the ages and into modern times. A passage of etymological reasoning is a characteristic element in Jacobus' tales, as Ryan notes:

To [Jacobus], a name is the symbol of the person who bears it, and in its letters and syllables can be found the indication of what the person's life, with its virtues and its triumphs, is to be. So he dissolves the compound of the name, so to speak, into its component elements; and he shows – frequently by recourse to Greek, of which he obviously knew little, and at times to Hebrew, of which he knew less – what the name meant when by the providence of God it was conferred on the future saint.

Ryan, ibid, p. xvii.

Jacobus was not in the least unique in this habit of using names as the proxies for the things to which they were attached – it was a widespread trait of all areas of medieval thinking. Of the name Lucy, Jacobus writes:

Lucy comes from lux, which means light. Light is beautiful to look upon; for, as Ambrose says, it is the nature of light that all grace is in its appearance. Light also radiates without being soiled; no matter how unclean may be the places where its beams penetrate, it is still clean. It goes in straight lines, without curvature, and traverses the greatest distances without losing its speed. Thus we are shown that the blessed virgin Lucy possessed the beauty of virginity without trace of corruption; that she radiated charity without any impure love; her progress toward God was straight and without deviation, and went far in God's works without neglect or delay. Or the name is interpreted "way of light."

Ryan's translation is precise, but we must mention Caxton's charming 'she passeth in going right without crooking by right long line; and it is without dilation of tarrying' for Rectum incessum sine curvitate, longissimam lineam pertransit sine morosa dilatione.

We mentioned in another context the mystical, almost Neoplatonic theorising of medieval schoolmen such as Richard of Saint Victor (?-1173) and Robert Grosseteste (c1175-1253), the latter a partial contemporary of Jacobus, on the subject of the metaphysical properties of light. Having a martyr named 'of light' is a feast for the metaphorical intellect.

And so it is for Jacobus. His purpose in this etymological passage on Saint Lucy is not to break new philosophical ground but to present the nature of light as manifested in the figure of Lucy in a way that could be grasped by the priests and preachers who could incorporate the materials from this wonderful source of anecdote and scriptural allusions into their own sermons. It is also a welcome opportunity to enhance the glamour of her life and her martyrdom.

It seems clear that the tales of the gouging out of Lucy's eyes were unknown to Jacobus, otherwise he would have had much metaphorical fun with the notion of the eyeless saint of light.

For the greater glory of God

Jacobus is a professional at this task, dutifully invoking the scriptures and the writings of the sound Fathers of the Church and adding some innocuous anecdotal colour. He was for forty years, after all, a member of the Dominicans, the Order of Preachers, and thus deeply familiar with the important task of mediating Christianity to the clergy and the laity. It is no wonder he rose to become an Archbishop and was eventually beatified.

We have slandered Jacobus' tales as being no better than fairy stories. In evidential terms that is clearly fair, but they are not simply tales written by a credulous simpleton for other credulous simpletons – their messages are structured with scholastic care to get across – directly or by implication – critical features of Christian doctrine. Hence their suitability for sermonising.

The Dominican aura emanating from the Legenda Aurea is one of its most important features. The Dominicans became the conservators and guardians of doctrinal orthodoxy in the Church of the time. The great Doctor Angelicus himself, Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274), was a Dominican contemporary of Jacobus (c.1230-1298).

Jacobus' Legenda Aurea was thus not some colourful book of tales to amuse the laity, it had a hard doctrinal purpose, as we can deduce from its original title Legenda Sanctorum, 'Readings on the Saints'. The Latin word legenda here having little do with the modern word 'legend' – for Jacobus it meant 'readings' and may have still contained a hint of its principal meaning in Classical Latin of 'collecting' or 'anthologising'.

In common with so many of the stories and sagas collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 19th century, however superficially incredible they are, they encapsulate some deep moral message such as fidelity, trust, filial piety and so on. In the same way, each segment of Lucy's life and martyrdom is freighted with a moral or some disputatious purpose. This is a Dominican writing.

The noble Lucy

Lucy, the daughter of a noble family of Syracusa, saw how the fame of Saint Agatha was spreading throughout Sicily.

The common people of the New Testament – the carpenters, tradesmen, tax collectors and fisherman – belong to a Jewish underclass eking out an existence under the Roman oppressor. Once that underclass, now Christianised, had been absorbed into the hierarchical systems of the Roman Empire and then into the feudalism of the Middle Ages we find it has developed its own brand of feudalism.

Thus, the first part of Jacobus' opening sentence about Lucy's life fixes in a handful of words her Sitz im Leben: a daughter of a noble (= rich) family in Syracuse. The modern proletarian wonders whether Lucy's martyrdom would have gained any attention at all had she not been of a 'noble family'. As we shall see, the problems that led to her martyrdom were not theological but financial.

Saint Agatha and intercession

The mention of Saint Agatha and her role in the first part of Lucy's biography is also critically important, establishing as it does a kinship with another, slightly earlier female martyr, a fellow Sicilian, whose story Jacobus also included in the Legenda Aurea. Saint Agatha is reputed to have perished in a brutal martyrdom around 250 AD, that is, thirty years before Lucy's reputed birth.

Jacobus tells us that Lucy's mother, Euthicia, had suffered for four years from dysentery – the 'bloody flux' as Caxton put it – perhaps these days we might call it Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Colitis or Crohn's disease. Lucy told her mother that she would be immediately cured were she to touch Agatha's tomb in good faith. Lucy fell asleep and had a dream in which she had a vision of Agatha in Heaven. Jacobus has Agatha say to her:

"My sister Lucy, virgin consecrated to God, why do you ask me for something that you yourself can do for your mother? Indeed, your faith has already cured her."

In this important statement, Jacobus raises Lucy to the status of her martyred predecessor, Agatha. He also underscores the doctrine of intercession: Lucy and her mother pray to Agatha to intercede with God to cure her distressing ailment.

This doctrine has been a central element in Christian theology since the earliest days, the belief that an intermediary can intervene with a higher power to grant someone's wishes. It creates a kind of chain of command to the Godhead – an idea which we atheist-agnostics find more than a little troubling, just one more of those feudal metaphors which characterise the relationship of Man to God as the relationship of the powerless serf to the all-powerful lord.

The Protestant sects, of course, dispensed with such Roman autocratic, crypto-feudal folderol in short order. In their world, every soul has direct access to God and requires no priest, no 'moth-eaten musical brocade' (©Philip Larkin) or saint in heaven to answer prayers and grant wishes.

Lucy herself now has the status of an intercessor – she is an example of the rare form of intercessionary power vested in the still living. Her martyrdom now takes on the character of an inevitability – almost a completion – much as the crucifixion of Christ was preordained for him. Even before her martyrdom, the manner of Lucy's life has been of such exemplary virtue. The Dominican lesson of this is that Lucy, through the manner of her life, her essentia as it were, had become a living saint before her martyrdom.

The rule of poverty

Her mother was healed, which in the circumstances comes as no surprise to us at all. What is surprising is that Lucy now promulgates her own theological doctrine, a form of extreme asceticism that repudiates all wealth – the Lord will provide, as it were:

"Mother, you are healed! But in the name of her to whose prayers you owe your cure, I beg of you to release me from my espousals, and to give to the poor whatever you have been saving for my dowry." "Why not wait until you have closed my eyes," the mother answered, "and then do whatever you wish with our wealth?" But Lucy replied: "What you give away at death you cannot take with you. Give while you live and you will be rewarded."

The celestial level of the narrative so far is suddenly brought down to earth by this example of a vulgar quid pro quo: in return for being healed Lucy's mother must now acquiesce in disbursing Lucy's dowry to the poor and not waiting until her mother has died to do this.

This is a monkish doctrine and in this plan of Lucy's we hear the voice of Jacobus de Voragine, the Dominican Friar – the Dominicans being not only a preaching order but a mendicant one, pledged to live in temporal poverty, relying only on the alms they received day by day. With this tale of the divestment of all worldly goods, Jacobus has effectively enrolled Lucy in his order.

Lucy's father had already been dead for some years, so that Lucy and her mother giving away all their wealth in the belief of divine support would have been no cause for concern to anyone had it not been for the presence of a betrothed, to whom Lucy and her once considerably dowry had been promised:

The wronged fiancé

Lucy's vision of progressive, pious impoverishment foundered on the presence of the would-be man in her life, her betrothed:

When they returned home, they began day after day to give away their possessions to satisfy the needs of the poor. Lucy's betrothed, hearing about this, asked the girl's nurse what was going on. She put him off by answering that Lucy had found a better property which she wished to buy in his name, and for that reason was selling some of her possessions. Being a stupid fellow he saw a future gain for himself and began to help out in the selling. But when everything had been sold and the proceeds given to the poor, he turned Lucy over to the consul Paschasius, accusing her of being a Christian and acting contrary to the laws of the emperors.

Note that in making a fool of her fiancé no lie passes Lucy's lips, the deception is effected by Lucy's nutrice, her nurse or handmaid. The woman is thus a useful agent, a Shabbat goy, employed to keep the would-be saint's hands impeccable. These days we would speak of deniability.

No man comes out of this tale of female empowerment unscathed. Lucy's stultus, her 'stupid' fiancé, is so dim that for a time, gulled by the nurse, he even helps Lucy to give away the dowry nominally intended for him, thinking that it will be to his profit. The legend treats him with the utmost contempt, to the point of leaving him, the Judas who rats on her, nameless.

The other man in the story at least is given a name, but comes off even worse than the nameless betrothed. He is Paschasius the consul, her judge, who is reduced to sputtering rage – 'all anguishous and angry' as Caxton put it – at Lucy's clever, self-confident parries and can only respond with threats and attempts at actual violence.

The despots, the guards, the would-be punishment rapists, the torturers and the executioners are all men and all fools and all made to look fools by Lucy, the young, empowered virgin. Her tale as a feminist tract for the 13th century? Why not?

Lucy's dialogue with Paschasius is lengthy and involved – the reader will be delighted to hear that we are not going to go into it in all its details.

Friar Jacobus develops the disputation with the flummoxed consul along the lines of the separation of temporal and spiritual authority famously defined by Jesus in Matthew 22:21: 'Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar's; and unto God the things that are God's.'

In a disputation of the type beloved of the schoolmen, Jacobus makes the young girl in effect tell the consul to go and mind his own business – his secular power has no authority over Lucy's soul and only Christ and God can be its master.

The disputation concludes with a defiant Lucy daring Paschasius to do his worst with her – confident that her soul will remain untouchable and unsullied. Ultimately, the literal-thinking Paschasius decides on a rape-fest to deal with this troublesome virgin:

Paschasius: "So the Holy Spirit is in you?" Lucy: "Those who live chaste lives are the temples of the Holy Spirit." "Then I shall have you taken to a brothel," said Paschasius, "your body will be defiled and you will lose the Holy Spirit." "The body is not defiled," Lucy responded, "unless the mind consents. If you have me ravished against my will, my chastity will be doubled and the crown will be mine. You will never be able to force my will. As for my body, here it is, ready for every torture. What are you waiting for? Son of the devil, begin! Carry out your cruel designs!" Then Paschasius summoned procurers and said to them: "Invite a crowd to take their pleasure with this woman, and let them abuse her until she is dead."

A fate worse than death

The use of rape as an assertion of male dominance is of course a major theme in the feminist canon. Lucy's assertion of her right to virginity and her rights over her own body sound very modern, though written 750 years ago and put into the mouth of a young woman who supposedly lived around 800 years before that.

The threatened rape party is arguably the central element in the tale of Lucy's martyrdom. The Master of the Figdor Deposition, realising this it seems, took some pains with the representation of the brothel – his detail shall be ours:

The brothel is a building which the artist has rendered with some care, even though it is a place which, as we shall learn shortly, Lucy never actually reaches. It takes up the upper third of the painting, but since it represents a major threat to Lucy by Paschasius, even if unrealised, its visual dominance is probably justified.

Since this illustration is part of an altarpiece we can expect and we get due modesty from the artist, albeit with not too subtle allusions. There are dark hints of drinking and licentiousness on the upper floor.

Through the window on our left we see an older woman with a headscarf, who seems to be the madam presiding over the goings on. She appears to be handing out the drinks. That ancient symbol of erotic hanky panky, the erect plumes, confirm what we imagine is going on through the right hand window.

Inside the dark entrance to the brothel we can just make out a couple embracing. The male and female figures sitting on the right of the door seem to be a social comment by the artist on the general theme of chastity. The young man's hand is wandering where it shouldn't wander and the girl is blocking its further progress with her left hand.

Her gesture with her right hand towards the open door of the brothel seems to be saying to the young man: 'if that's what you want, then go somewhere where you can get it.' Others can take up the tricky discussion of the preservation of the souls of the chaste at the expense of the souls of the working girls.

Resistance

Lucy's fortitude in the face of being raped to death is ultimately not tested. The Holy Spirit, the engine of God's action at a distance, prevents this happening:

But when they tried to carry her off, the Holy Spirit fixed her in place so firmly that they could not move her. Paschasius called in a thousand men and had her hands and feet bound, but still they could not lift her. He sent for a thousand yoke of oxen: the Lord's holy virgin could not be moved. Magicians were brought in to try to move her by their incantations: they did no better. "What is this witchery," Paschasius exclaimed, "that makes a thousand men unable to budge a lone maiden!" "There is no witchery here," said Lucy, "but the power of Christ; and even if you add ten thousand more, you will find me still unmovable." Paschasius had heard somewhere that urine would chase away magic, so he had the maiden drenched with urine: no effect.

The artist goes into detail with this episode, although he wisely ducks Jacobus' wild hyperbole of the thousand men and the thousand pairs of oxen. The gentleman with the ladle of urine is not overlooked, though.

As an aside whilst we are looking at this detail, we expect the eyes of the historians of the medieval period to light up at the fine and detailed representation of traditional medieval strip farming on the hill in the background. Even the crop rotation is visible.

Although her persecutors failed to move her to the brothel, she now appears to permit her progress to the place of her execution. The painter has taken some trouble to illustrate the procession of Lucy, led by the chief executioner in his natty armour, past the front of the brothel to the place of execution. The figure of the solitary, radiant young woman contrasts dramatically with the crowd of helmeted soldiers crammed into the narrow ginnel along the side of the brothel.

The lack of a narrative transition in Jacobus' tale between the immobile Lucy and her transit to her execution is puzzling. It seems that the Holy Spirit moved to prevent her physical, sexual desecration and humiliation in the brothel, but willingly allows her free passage to her martyrdom by fire.

The painter has solved this narrative break with his elegant invention of the journey to the execution, the which device brings the added value of a fine visual contrast between the girl and her tormentors.

She is shown apart from the mob, almost aloof. Two of the guards have hold of her, but we have no sense of dragging or even leading. Lucy is in complete control of this situation. As for her appearance, we come back to Jacobus' opening sentence: 'Lucy, the daughter of a noble family of Syracusa'. The painter has rendered her as richly dressed – no mendicant pauper here. Compare her clothes, for instance, with the much plainer dress of the girl defending her chastity in front of the brothel. Lucy's exceptionalism is on clear display here.

The fire and the sword

Next the consul, at the end of his wits, had a roaring fire built around her and boiling oil poured over her. And Lucy said: "I have prayed for this prolongation of my martyrdom in order to free believers from the fear of suffering, and to give unbelievers time to insult me!" At this point the consul's friends, seeing how distressed he was, plunged a dagger into the martyr's throat; but, far from losing the power of speech, she said: "I make known to you that peace has been restored to the Church! This very day Maximian has died, and Diocletian has been driven from the throne. And just as God has given my sister Agatha to the city of Catania as protectress, so I am given to the city of Syracusa as mediatrix."

In the execution scene the Master of the Figdor deposition has taken the artistic licence to depart from the strict representation of Jacobus' description. The imagery of the written description of the execution scene is anyway rather weak: no other participants are mentioned apart from Lucy herself, the consul and some anonymous 'friends' of his. Jacobus deals with the practicalities of the execution scene in sixteen Latin words.

In contrast, the painter has brought this scene alive with detail. The saint herself is immaculate, neither her body nor her dress has been damaged by the flames. One man is using a bellows to force the fire, but we think we see a sense of desperation in the frantic puffing. The same is true of the man adding faggots to the already ineffective blaze.

We see that one bellows blower has withdrawn from the task, the pose suggests not only exhaustion but also puzzlement, perhaps even sorrow or self-doubt. It may be that the heat of the flames has become too much for him – the other bellows blower and the faggot scooper seem to be keeping low in order to avoid the worst heat of the fire

The finely armoured soldier we first encountered on the way to the execution is stabbing his sword into Lucy's throat in a remarkable, dynamic thrust. The boiling oil of the written narrative rightly finds no place here – understandably, since the visual situation is already bad enough, without the potential confusion of the pouring of boiling oil. In Jacobus' tale, it is the amici Paschasii, 'the consul's friends', who stab Lucy through the neck. Here the painter shows us Lucy being stabbed with a sword by the ornately costumed soldier, which is a slightly more realistic scenario.

The attempt to silence Lucy in the course of her unwelcome utterances with a sword through the throat has, of course, heavy metaphorical echoes of those who attempted to hinder the work of spreading the gospel, particularly during the years of the early church. It does not succeed – on the contrary it leads to even more unpleasant prophesies of the fate of the oppressors of the early Church, particularly the fall of Diocletian and the rise of Constantine.

To one side from the execution itself, the painter has rendered Paschasius (who wears a green robe throughout the tale) 'at the end of his wits', possibly being comforted by his friends.

It seems more likely, though, that the painter is showing us the seizure of Paschasius by the ministri Romanorum, 'envoys from Rome', in which case the arm on his shoulder is not a gesture of comfort but a sign of his arrest. The two prominent and splendidly attired figures at the front of the group seem to be watching events with concern, perhaps even sorrow, and thus may also represent the senior envoys who have come to collect Paschasius and take him back to Rome to account for all his other misdeeds.

Why are we shown Roman functionaries wearing turbans reminiscent of the pashas of the Ottoman empire?

In order to answer this we have to recall that the memory of the Roman Empire in the West faded rapidly after its fall in the fifth century. Within the space of a few generations no one had any idea what these Roman remains were, or what the people looked like who once lived there. The Classical world was completely forgotten. Although the empire in the east, based on Constantinople, kept on going for another eight centuries or so, that, too, for most people in western Europe, was a strange, distant, legendary place.

However, from around 900 AD until the middle of the 18th century, successive Muslim caliphates left their mark on the countries around the Mediterranean. Those images of the Greek and Roman world with which we are now so familiar only came into the cultural currency of the West during the Renaissance in the 15th and 16th centuries, with the rediscovery of the Classical world. Before that, illustrators drew the heathens they knew, the Muslims of the medieval caliphates. They knew nothing of the elegant toga'd figures we now associate with the warm Classical world – the heathens and infidels of the medieval Christian world were all considered to dress like the rich nabobs of the Arab world.

Taking back control

While the virgin was still speaking, envoys from Rome arrived to seize Paschasius and take him in chains to Rome, because Caesar had heard that he had pillaged the whole province. Arriving in Rome he was tried by the Senate and punished by decapitation.

The seizure and execution of Paschasius is sufficiently important for the painter to include it in the top right hand section of the painting. The now ex-consul, still wearing the green robe that has figured throughout the rest of the painting, is being beheaded.

It is an almost universal feature of tales of martyrdom and oppression in the Roman Church that, although the martyred and the oppressed are lifted into eternal life in Heaven, the wrongdoers on Earth get their just desserts. We feel that the martyrdom of Saint Lucy would not be complete without being concluded by Paschasius' downfall.

As for the virgin Lucy, she did not stir from the spot where she had suffered, nor did she breathe her last before priests had brought her the Body of the Lord and all those present had responded Amen to the Lord. There also she was buried and a church was raised in her honor. Her martyrdom took place about the year of the Lord 310.

Some variants

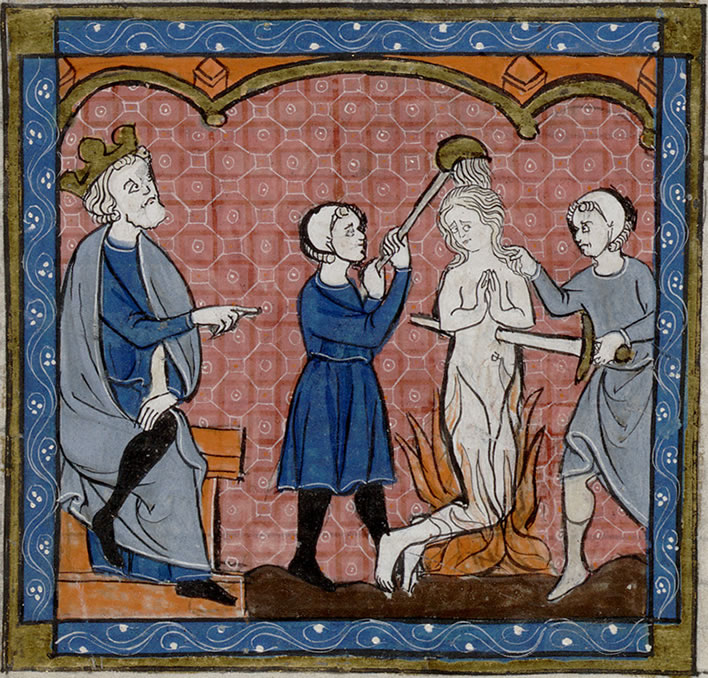

There are more representations of the martyrdom than we care to deal with here. They all show the role of the creative imagination of artists in illustrating the scene. The illustrator of one of the manuscripts of the Legenda Aurea, for example, manages to pack most of the action around the execution into the small space at his disposal. He renders the flames and the boiling oil, but the sword is thrust through her body, not her neck. In this strand of the tradition, her eyes are still in her head:

Illustration for the entry for Lucia in the manuscript of the Legenda Aurea in the Huntington Library, California. This richly illustrated manuscript copy is considered to have been produced between 1270 and 1280 in Paris. Image: Digital Scriptorium Database.

A fifteenth century image has the martyr fastened to a stake, there are bellows and boiling oil or pitch. Surprisingly, the sword, the object most associated with Lucy, is still at rest in the hands of one of the observers. Her eyes are also intact.

Bernat Martorell (1390–1492), Martirio di Santa Lucia, 1435-1440 Image: Museo nazionale d'arte della Catalogna.

An image from the Nuremberg Chronicle of c. 1493 shows Lucia martyr with her most iconic attribute, the sword rammed futilely through her throat. Her eyes are also intact.

'Lucia Martyr', from Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514), Nuremberg Chronicle c1493. Image: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek / Münchener Digitalisierungzentrum.

Dante's women

The group of the 'seven women in heaven' introduced into the Canon is of great importance in Catholic theology. At this point, Dante scholars will be itching to write about them, particularly Saint Lucy, who is given a major role in the Divina Commedia. The period of the composition of the book, c. 1308 to 1320, represents an important waymarker on the route taking Saint Lucy to her current canonical position. We'll take a brief sweep past the Dantescan Lucy and leave all the other female intercessors for others to write about.

In Canto I of the first book of the trilogy, the Inferno, Dante has strayed from the true path and has got lost in the Dark Wood. He tries to escape the wood by climbing a beautiful mountain (Mount Purgatory), but is turned back by three beasts, a leopard, a lion and a she-wolf. He is about to return to the Dark Wood, but is intercepted by the shade of Virgil, who tells him that he can only complete his journey by putting his faith in him and following him down the longer path through Hell and Purgatory. There is no shortcut to heaven, it seems.

In Canto II we find that Dante, faced with the challenging journey, is losing heart and starting to make excuses for not continuing. In order to spur him on, Virgil explains the origin of the journey he is undertaking [Inferno II.94-126]. We learn that Virgil's appearance to Dante at that moment of despair in the Dark Wood was in fact the result of the intervention of a triad of females who, most scholars feel, represent different aspects of the Divine Grace: Beatrice, Dante's great love, had been prompted by Saint Lucy, who herself had been prompted by the Virgin Mary, to descend into Limbo, the place where the souls of the unbaptised of the ancient world repose, to ask Virgil to go to Dante's rescue in the Dark Wood.

Saint Lucy performs another critical service for Dante, this time in the second book of the trilogy, the Purgatorio. After conversing with the spirits on the terrace of the 'Late Repentant' (those souls in the 'Ante-Purgatory' who only repented of their sins on their deathbeds), Dante falls asleep. He has a dream, the content of which does not concern us here, but when he awakes he finds that he has been carried up in his sleep by Saint Lucy to the Gate of Purgatory itself [Purgatorio IX.49-63].

Lucy's intervention is a narrative device which gets Dante past the Three Steps of Penitence needed to get to Saint Peter's Gate. The device is needed because, since Dante is only visiting Purgatory and Paradise, there is no need for him to submit to the rigmarole required to pass the Three Steps of Penitence. Saint Lucy is clearly taking her role as enabler on Dante's journey seriously.

Our final encounter with Lucy comes in the Paradiso, where Dante sees Saint Lucy in her alloted position in the circle of the 'Saints in the Empyrean', where she sits opposite Adam [Paradiso XXXII.136-138]. Explaining such calculated juxtapositions has put food on the tables of Dante scholars for eight centuries.

Chronicle

Readers whose heads are spinning with all these dates – all of you, admit it – may find a brief table of dates useful. A question mark should be placed alongside most of these dates:

| 231 | Agatha born |

| 251 | Agatha martyred |

| 283 | Lucy born |

| 284 | Diocletian's reign begins |

| 304 | Lucy martyred |

| 305 | Diocletian's reign ends |

| 324 | Constantine the Great's reign as sole ruler begins |

| 337 | Constantine the Great dies |

| 480 | Collapse of the Western Empire |

| 500 | Lucy enters the Roman Canon |

| 970 | Lucy's bones arrive in Metz |

| 1038 | Georgios Maniakes takes Lucy's bones to Constantinople |

| 1204 | Constantinople sacked, Lucy's bones taken to Venice |

| 1225 | Thomas Aquinas born |

| 1230 | Jacobus de Voragine born |

| 1260 | Jacobus de Voragine writes the Legenda Aurea |

| 1274 | Thomas Aquinas died |

| 1279 | Lucy's bones transferred to Church of Santa Lucia in Venice |

| 1298 | Jacobus de Voragine died |

| 1320 | Dante's Divina Commedia finished |

| 1453 | Collapse of the Eastern Empire |

| 1483 | William Caxton's translation of the Legenda Aurea in English |

| 1493 | Nuremberg Chronicle |

| 1505 | The Master of the Figdor Deposition, The Martyrdom of St Lucy |

| 1608 | Caravaggio's Burial of Saint Lucy |

| 1860 | Lucy's bones transferred to Church of San Geremia in Venice |

| 1955 | Venetian skull gets silver mask |

| 1981 | Venetian remains kidnapped for 36 days |

The new age

Jacobus' text was produced around 1260. The images we have looked at so far were all produced in the two-and-a-half centuries after that. The altar panel by the Master of the Figdor Deposition, done around 1510, forms the last example of this group.

The final painting we are going to look at in our meditation for Saint Lucy's Day 2019 is Caravaggio's (1571–1610) breathtaking work The Burial of Saint Lucy, done around 1608. It hangs in the church of Santa Lucia al Sepolcro in Syracuse. Done only one century after the Figdor panel, it brings home to us the breathtaking changes that occurred in the culture of Europe in the intervening 16th century.

The genius of Caravaggio has caused him to disdain all pictorial storytelling, ignore all static scenes from the martyrdom and go straight to the emotional heart of the legend of Lucy's martyrdom. Put somewhat pretentiously, he has gone past the narrative structure of her story to uncover its emotional correlative. He can anyway assume that his audience all know the narrative and need no help from him to recall it.

Here is the full painting:

Caravaggio (1571–1610), The Burial of Saint Lucy, c.1608. Image: Wikimedia [Click on the image to open a larger version in a new browser tab].

We are looking at the work of a genius and a fearless innovator. Only a fearless innovator would fill the top half of his painting with a rendering of a scruffy brown wall. But – who dares, wins: this bravery focusses our attention on the huddled line of mourners who take up the third quarter of the painting. The line is not horizontal, but slopes gently downwards to the left:

Readers are perfectly capable of drawing their own conclusions about these mourners, the types of people they represent and the types of grief they exhibit. The strange, bulky, armour-wearing figure on the extreme right is worth our attention, though.

Despite his marginal location, there is no doubt that, from his sheer bulk, he is one of the dominant figures in the composition. The blade of his sword is well defined, which is surely no accident. Is this the blade that was thrust into her neck? Is the soldier here to keep order among this Christian rabble, or himself to mourn? Is he the symbol of the earthly power that put her to death? Unfortunately the degraded state of the painting gives us no chance of an answer.

When we take this section of the painting as an image in itself, we find a breathtakingly clever composition: The head and shoulders of the dead Lucy are located at the intersection of the vertical and horizontal golden sections within this part of the painting. Not only that, they are encircled by the figures of the two gravediggers, whose legs and whose spades lead our sight down into the ground.

The image of Lucy's head and shoulders glows out of that characteristic Caravaggio darkness at us. And what an image! Here is no medieval saint, suffering fire, boiling oil and the sword with serenity. Here we have the body that death has left behind, the body of a young woman with the face of someone we might encounter nowadays on any day on any street.

The body has not been laid out or presented for burial in any way that we would consider fitting– it has been laid on the ground, the head rolled back, the mouth unclosed, the skin unwashed. The arm is already partially covered by soil – all hints of urgency that we might expect from a persecuted religion. We could be looking at the murder victim at a crime scene.

The eyes are not closed, either – they are not there: only when we look closely do we notice the hollow sockets where eyes once were and the wound in her neck where the sword entered.

The rest of her body is dark, possibly charred by flames, a colour that merges into the ground which will soon accept her. The fire was not a cremation, but a torture. Part of her bodice appears to have been stained by the blood that flowed from her wounded throat. Her arm lies in the dirt. Only the highlight on her face and shoulders brings the saint of light out of the deep physical darkness behind her, a darkness into which she herself is about to descend.

Caravaggio's greatest triumph in this painting is to have created a Saint Lucy in whom even grumblers and doubters such as we atheist-agnostics can believe, despite our rationalist selves. Perhaps we wizened pedants need to give more weight to the faint imprints of a girl's silken slippers in the ashes of history.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!