Franz Schubert and Franz von Schlechta

Richard Law, UTC 2020-01-17 16:43

We recently carried out a textual and contextual analysis of Franz Xaver Freiherr Schlechta von Wssehrd's (1796-1875) poem Fischerweise, set to music in 1826 by Franz Schubert as D 881.

Schlechta's relationship to Schubert has scarcely been studied. No modern scholar has the slightest interest in Schlechta's literary ephemera – Ephemeren, 'Ephemera', being the highly accurate, perceptive and prescient title he gave to his last collection of his poetry. Schlechta's presence in Schubert's biography is shadowy at best, their relationship is consequently incoherent.

In this vacuum the best we can do at the moment is just to draw attention to their differing paths and the instances when those paths crossed. Theirs was a long relationship which began in 1813 when their paths first briefly crossed in the Vienna Stadtkonvikt.

In the Stadtkonvikt

The almost seventeen year-old Schlechta arrived there in the autumn of 1813 from the Kremsmünster Stift (along with Joseph von Spaun's brother, Max). The Stift was a boarding school in Kremsmünster, Lower Austria, run by the Dominicans. Kremsmünster is about 30 km from Linz and about 180 km from Vienna.

In the Vienna Stadtkonvikt, one arrived and one left: Schubert, then sixteen years old, his voice broken and his head ditto, resigned from the Akademisches Gymnasium and the Stadtkonvikt in November 1813. We are assuming that the two met early on, but this overlap was not long: the idea that the two young men met during that period is thus speculative, but not unreasonable.

Drawing by Salomon Kleiner (1700–1761) of the Jesuit Church (centre) and the Jesuit Kollegium (right) in 1724. The Stadtkonvikt was housed in the Kollegium from 1802 onwards. The building on the left became the Aula of the university. Image: Österreichisches National Bibliothek.

Schlechta left an early mark on Schubert history with the grumbling letters he wrote from the Stadtkonvikt to his friend Franz von Schober, still in the Kremsmünster school. Schlecta was in the Stadtkonvikt to complete the two years of the superiora, the philosophy classes in the Akademisches Gymnasium attached to the Stadtkonvikt, after which he would board there whilst studying Law at the nearby University of Vienna.

Since in our present era of the Gretaceous we are bidden to take the opinions of teenagers seriously, let's get a taste of the seventeen year old Franz Schlechta's opinion of the Stadtkonvikt, which was his world at the time. Shortly after starting there, he wrote to Schober:

I am not happy in the Konvikt, in particular I dislike the angry faces the Prefects make. Another time [I'll write] more.

Ich bin nicht im Convicte zufrieden, besonders mißfallen mir die bösen Gesichter, die uns die Hn. Präfekten machen. Ein anderesmal mehr.

[Konvikt p. 487, 28/29 November 1813.]

Schober has seemingly already acquired his lifelong, lazy habit of ignoring the letters of those meaningless moths who fluttered reverentially around his flame, replying to them only if he really had to. Schlechta, the sensitive aesthete, after a month of waiting for the god to acknowledge him, sent a plaintive stream of consciousness letter to him once more. Perhaps this would arouse his idol's pity and thus move him to respond:

Since you haven't written I shall once again describe my situation [and] our magnificent entertainments during this Christmas holiday, just imagine, friend! a circle of the most stupid, crudest people, who do nothing other than happily drink and play games, a dusty, almost revolting room, dusty boots, drinking glasses, uniform stands, hat cases, boot trees, old trousers, shabby novels, chamber pots, bottles, brushes, tables and cupboards full, in addition a caretaker the polar opposite of the Prefects, those bulldogs of Director Schönberger etc. etc. not even considered – and you will know my physical surroundings. So I have only that mood which overcomes me just looking at my new colleagues, even though I usually repress it, – I feel so confined, so tearful – when I, chained to my desk, think of home, of you all, my loved ones! when I see the friendly sky, where every bird happier than I, freer than I, spends its existence, the most beautiful, better part I have to trust – and so I stood today, too, in the open window of our corridor, saw the blue sky, decorated with clouds, thought of you all, thought how it vaulted over you also, how you also see it, but cheerful and happy, how differently to me! – However, this mood will pass once more, until we can breathe freely, which means, turn our backs often on the prison!

Ich will Dir jetzt einmal, weil Du nicht schreibst, meine Lage, unsere prächtigen Unterhaltungen dieser Weihnachtsferien schildern, denke dir nur, Lieber! einen Kreis der dümmsten rohsten Menschen, die nichts als gerne saufen und spielen, ein staubiges, fast ekles Zimmer, staubige Stiefel, Trinkgläser, Wichshäfen, Hutfuterale, Stiefelhölzer, alte Hosen, lumpige Romane, Töpfchen, Flaschen, Bürsten, Tische und Kästen voll, dazu einen Wirthe mit Antipoden zum Präfekten, der Bullenbeißer von Direktor Schönberger etc. etc. gar nicht gedachtet – und Du wirst meine lieblichen Umgebung kennen. So bleibt mir meistens jene Stimmung, die mich beim bloßen Anblick meiner neuen Mitkollegen anwandelte, wenn ich sie auch meistens unterdrücke, – es wird mir so enge, so weinerlich – wenn ich so oft angefesselt am Pult nachhause, an Euch, Ihr Lieben! denke, wenn ich den freundlichen Himmel sehe, wo jeder Vogel froher als ich, freier als ich sein Dasein verlebt, dessen schönsten besseren Teil ich vertrauen muß – und so stand ich auch heute im offenen Fenster unsers Gangs, sah den blauen Himmel, den weiße Wolken umkräuselten, dachte an Euch, dachte auch über Euch wölbt er sich, auch ihr seht jetzt ihn froh und glücklich, wie verschieden gegen mich! – Doch sie wird wieder vergehen diese Stimmung, bis wir wieder freier atmen können, das heißt, öfter dem Gefängnisse den Rücken kehren!

[Konvikt p. 487f, 30 December 1813.]

Those heroic readers who plugged through our piece on the poetic defects of Schlechta's Fischerweise and even more so those poor galley slaves such as your author who have rowed across the queasy undulating sea of Schlechta's collected poems will read the young author's over-sensitive and maudlin letters to Schober and say to themselves: 'Yes, that's him'.

Still, despite his grumbling, he survived his time in the Stadtkonvikt, proved his academic abilities and set his feet firmly on the ladder of promotion in the imperial civil service. The fact that his father was made a baron in 1819 was certainly a help in his career.

The question of whether Schlechta's juvenile adoration of Schober persisted into his later life is just one of those many questions we cannot answer – take a ticket and wait your turn. Also unanswerable at the moment is the even more puzzling but interesting question of how the Schober-Schlechta axis and the Schober-Schubert axis aligned – in the modern argot, how did Schober run his two bitches? Since we don't even have a certain date (1815?) for when Schober recruited Schubert to the discipleship, we are struggling with that one, too.

Schubert had left the Stadtkonvikt by the time Schlechta wrote these letters, but we know that he returned there from time to time to meet his old comrades and to play them his new compositions.

The Kremsmünster circle

Despite the brevity of this first encounter, Schlechta's acquaintance with Schubert appears to have deepened over the next few years. Being one of the boys from Kremsmünster school, Schlechta had an automatic entry into the group of ex-Kremsmünster pupils who were close to Schubert: the Spauns (Joseph and Max), Mayrhofer, Stadler, Kenner, Kreil, Huber, Schober (of course) and even, from much earlier days, Michael Vogl.

We can therefore safely assume that Schlechta and Schubert can be said to have been friends to some degree. To what degree we do not know: whereas all of these Kremsmünster boys pop up in the narrative accounts of Schubert's life, Schlechta is rarely mentioned. However, we encounter isolated pieces of evidence that point to some sort of an ongoing relationship.

For example, Schlechta was a singer in a performance of Schubert's Prometheus Cantata (D 451) on 24 July 1816; in that year he wrote a poem about Schubert and the cantata entitled An Herrn Franz Schubert, which he managed to get published a year later in the Wiener Allgemeine Theaterzeitung on 27 September 1817, after he had become a contributor to the journal. [Dok 47] In that role over the next few years he wrote benevolent reviews of the rare occasions on which works of Schubert managed to get a public performance.

Schubert's settings of Schlechta's poems

In addition to the smattering of biographical information about the two, we know that Schubert set a total of seven of Schlechta's poems, scattered through his life. With poets he did not know personally Schubert had the habit of setting a number of that poet's works as a block before moving on to someone else.

In Schlechta's case the seven compositions stretch out through most of Schubert's adulthood. This is another indicator of an ongoing acquaintance or friendship in which Schlechta places from time to time a work on Schubert's composing conveyor belt. The seven songs fall into two temporal clusters: the first four came in their young days, the final three in a group in the mid-1820s.

The first of Schubert's settings was of Auf einen Kirchhof (D 151) in 1815; the second setting, of the poem Aus Diego Manazares (D 458), came in 1816; the third was of the poem Widerschein (D 639) in 1818 (it is thought). There are two variants of this text which result from Schlechta's habit of fiddling retrospectively with his poems.

In 1820 Schubert set his fourth Schlechta poem Des Fräuleins Liebeslauschen (D 698). Thus, four of the seven Schlechta poems were set in Schubert's first five years as a song composer.

The process of the composition of this fourth poem is quite remarkable, in that the presence of extensive corrections in a foreign hand (apparently Schlechta's) in the manuscript score shows the poet revising his own text in the context of Schubert's music. All the many changes that were made continued to fit the melody – an instance of a poet having second thoughts on his text as a result of Schubert's musical analysis.

The collaboration on this project was clearly close. Consider: Schubert would have had to give Schlechta access to the manuscript score and he in turn would have had to return the score to Schubert. It is inconceivable that Schubert would have handed over his score and let Schlechta do what he wished without further ado.

Schlechta even continued to fiddle with the text of his poem in versions which appeared in 1820 ('Conversationblatt'), 1824 (Schlechta's volume), 1832 (Schubert's published score) and 1876 (Schlechta's great rewrite of his poems). [Dürr 101f.]

The title page of the 1828 edition of Dichtungen vom Freyherrn Franz von Schlechta. Source: Klassik Stiftung Weimar / Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek.

After 1820 there follows what appears to be a five year fallow period in their artistic relationship, until in 1825 Schubert set his fifth Schlechta poem Des Sängers Habe (D 832). In 1826 came the sixth, Totengräber-Weise (D 869) and the seventh (in March), Fischerweise (D 881). This burst of activity may have had something to do with the publication of Schlechta's volume of verse in 1824. Or perhaps not, as the case may be.

1826: Schlechta and the Schubertiaden

Although during the 1820s we have no narrative of the relationship between Schubert and Schlechta, Schlechta is mentioned in passing in a handful of observations by others.

For example, in the weekly 'Schubertiaden without Schubert' that were held by Karl von Enderes in the period following Schubert's illness, we read in a letter of Schwind's to Schober on 14 February 1825 that Schlechta was among the dignitaries present at these events ('a mixture of the same faces'). [Dok 275]

Nearly two years later we read Franz von Hartmann's diary entry for 15 December 1826, in which he tells us of a 'great great' Schubertiade at Joseph von Spaun's house. [Dok 388] He tells us that Die Gesellschaft ist ungeheuer, 'the society was tremendous'.

In his list of the great and the good who who had gathered at Spaun's he records the presence of Baron Schlechta und andere Hofkonzipisten und -Sekretärs, 'Baron Schlechta and other court administrators and secretaries'.

We recall that the brothers Fritz (1805-1850) and Franz Hartmann (1808-1875), from whom we gain so much priceless gossip from this time, were in Vienna between 1824 and 1828 completing their Law studies, which would soon set them on the ladder into the imperial civil service.

This is the context in which we find them carefully scanning those present and noting who was who. Their sensitivity to rank and status is quite illuminating. Schlechta is named specifically and thus was clearly one of those worthy of note to the aspiring civil servants. But in another a listing by Hartmann of what we might term the coffee house circle around Schubert, there is no mention of Schlechta. [Litschauer 86] Indeed, Franz Hartmann's note on Schlechta's presence at the 'great great' Schubertiade hints at a certain distance between the two students, who themselves had been rapidly assimilated into the inner circle of friends, and the civil servant.

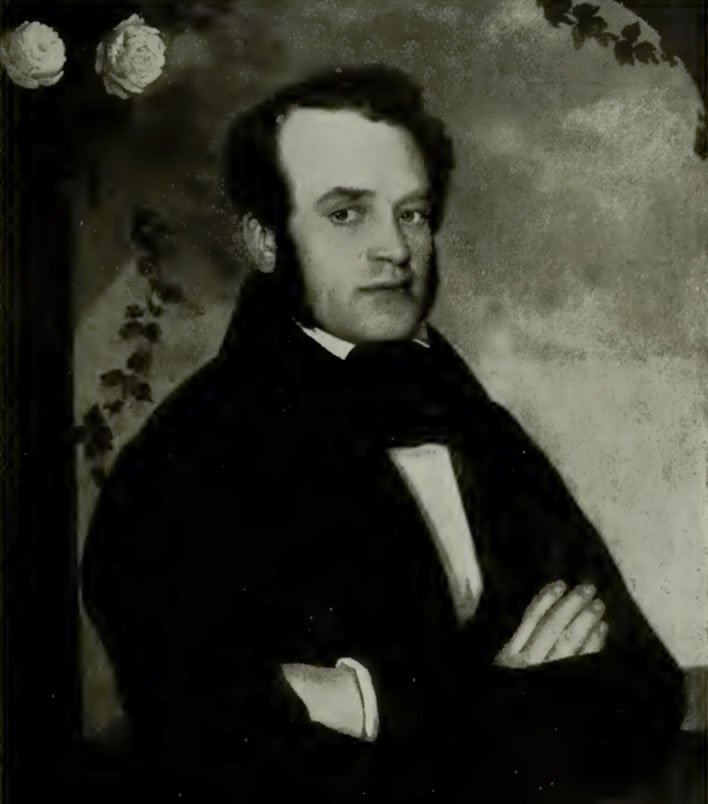

Heinrich Hollpein (1814-1888), portrait of Franz Xaver Schlechta Freiherr von Wssehrd, 1835. Image: hanging on someone's wall.

1827: Schlechta and Nina

A few months later, in April 1827, Eduard Horstig (1795-1828) a gifted and promising member of a noted family, who was at that time a relatively elevated administrator in the imperial court chamber in Vienna, wrote to his parents in Bückeburg (in Lower Saxony, north-west Germany) describing a particularly glittering evening in the house he shared with his aunt in Vienna.

Große Abendgesellschaft bei uns, 'great evening gathering here', he wrote to his parents in on 10 April 1827, and went on to list the glitterati in this large gathering. In Eduard's list of the cluster of barons in attendance we find Baron Schlechta, once more noted by name. [Dok 421]

Our telegram-style description of that evening does not really do justice to the situation, since it misses out the key figure: Nina.

Eduard Horstig and his sisters Liane and Fanny were staying with his aunt Nina d'Aubigny von Engelbrunner (1770-1847) in a splendid apartment in a palatial house in the Riemergasse belonging to Prince von Paar.

A description worthy of Nina would take up an entire article. She was widely travelled, spoke and taught a number of languages, was a prolific author and a fine contralto singer, pianist and harpist. After settling in Vienna (1825-1828) she threw lavish parties attended by large numbers of the cultured great and the good. During those three years, in her person and in her salon, Nina united the academic, literary and musical worlds of Vienna.

Eduard's letter, a seeming footnote in the Schubert biography, cracks open a door on Schubert's life just wide enough to give us a frustratingly brief glimpse of Schubert's contacts with the high-level cultural circles in Vienna.

Unlike at the later concert for Charlotte Kinsky, which also cracked a door open for us, in Nina's salon Schubert was not simply the little piano player whom no one recognised – many of Schubert's friends were at Nina's party too: Anselm Hüttenbrenner, Grillparzer, Schlechta. Eduard also tells us that the tenor Ludwig Tietze (1797-1850), accompanied by Schubert, sang Schubert songs and Beethoven's setting of Friedrich von Matthisson's Adelaide, the latter possibly in memory of Beethoven (revered by Nina and Schubert) who had died only a few weeks before, on 26 March.

It seems unlikely that this was the only time that Schubert turned up at Nina's frequent events, but this parallel world of Schubert's appearances in wider Viennese society and cultural circles has so far gone unnoticed. Popular Schubert mythology obsesses about the cosy Schubertiaden and the fantastical Freundeskreise, because that is where the easily available reminiscences are. It is high time – long overdue, in fact – that we gave these cracked doors a shove and looked at Schubert's part in the wider world of Viennese society in the late 1820s.

Eduard Horstig had been in poor health for most of his adult life and died in the year after this event, in October 1828, probably from tuberculosis. For Nina the frantic gaiety of her life died with him – she withdrew from society and withdrew from Vienna to Graz. That autumn and winter of 1828 was indeed a bad year in one way or another for Viennese music.

1828: the last year

Which brings us to 1828. The early part of 1828 is an interesting time in the Schubert-Schlechta relationship. The pieces of information we have are all frustratingly disconnected. It is foolhardy to begin fantasising a greater context on all these fragments, but let's take the risk.

There are three key events that we know about which are relevant to Schlechta. Firstly, the Spaun Schubertiade on 28 January, the last one ever. Secondly, the Private Concert on 26 March. Thirdly, the concert and dedication for Charlotte Kinsky which took place sometime around the beginning of July. After that, the summer lull set in and the social whirl of Vienna spun down. By the time it spun up again, Franz Schubert was dead.

The last Schubertiade

In terms of the relationship between Schubert and Schlechta, what is interesting about the last Schubertiade at Joseph von Spaun's apartment on 28 January 1828?

Interesting is the fact that Franz Hartmann leaves a brief description of the event in his journal but makes no mention of Schlechta. However he does tell us that about 50 people were present. [D 485f] Well, that's not conclusive of anything.

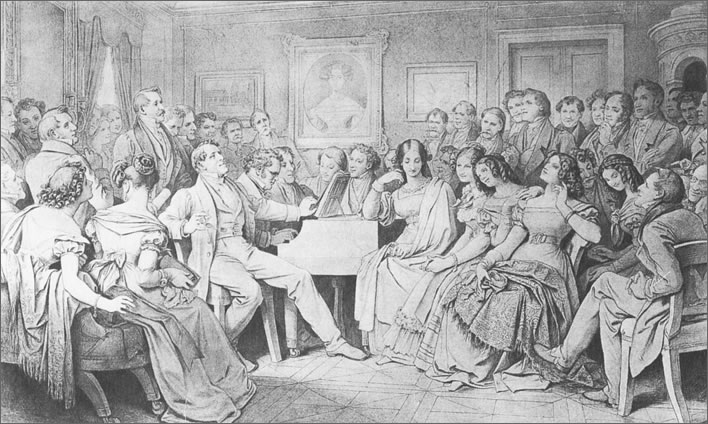

However, when Moritz von Schwind reconstructed this event from memory nearly forty years later, he didn't include Schlechta in the company, either. This is also not conclusive of anything, because Schwind was not illustrating figuratively and accurately a real event. Schwind's portrait is not a record of that or any other particular Schubertiade, but is a generic representation of those close to Schubert.

Moritz von Schwind's homage Ein Schubert-Abend bei Josef von Spaun, 'A Schubert evening at Josef von Spaun's'.

That is why we find Franz von Bruchmann (1798-1867) and Johann Senn (1795-1857) lurking in the shadows at the back on the right. Bruchmann may have been present on that 28 January 1828, but Senn certainly wasn't – he had been festering in his Tyrolean banishment since 1821, in which he would continue to fester miserably until his death thirty years on.

Schwind and Bruchmann both visited him during his Tyrolean exile. Senn is one of the most important figures in the Schubert biography – it would have been a very different biography if Senn could have remained at Schubert's side. Schwind knew Senn had to be in this panoptic gathering of Schubertians, in which he now stands in the shades as the Ghost of Schubert Past.

Schwind shows us another event in the biography which had long been resolved by 1828: Schober's secret 'engagement' to Justina von Bruchmann. We see Schober and Justina bent down low in the second row, carrying on a flirtatious conversation during the performance. That relationship was broken up in 1823. We can guarantee that they would not be sitting together like that in 1828: in the years prior to this painting, Schwind had gone from worshipping Schober to detesting him – now we are shown Schober being much more interested in the rich Justina than Schubert and Vogl's performance. Clearly, a dish best eaten cold.

As we scan the faces of all these people who played some role in Schubert's life, we miss one who is currently on our minds: Franz von Schlechta. Can it be that Schwind, forty years after the fact, forgot about this avid Schubertian? Even if Schlechta had not attended that particular final Schubertiade at Spaun's, Schwind would have had every reason to include him in the gathering. Make of it what you will.

The Private Concert

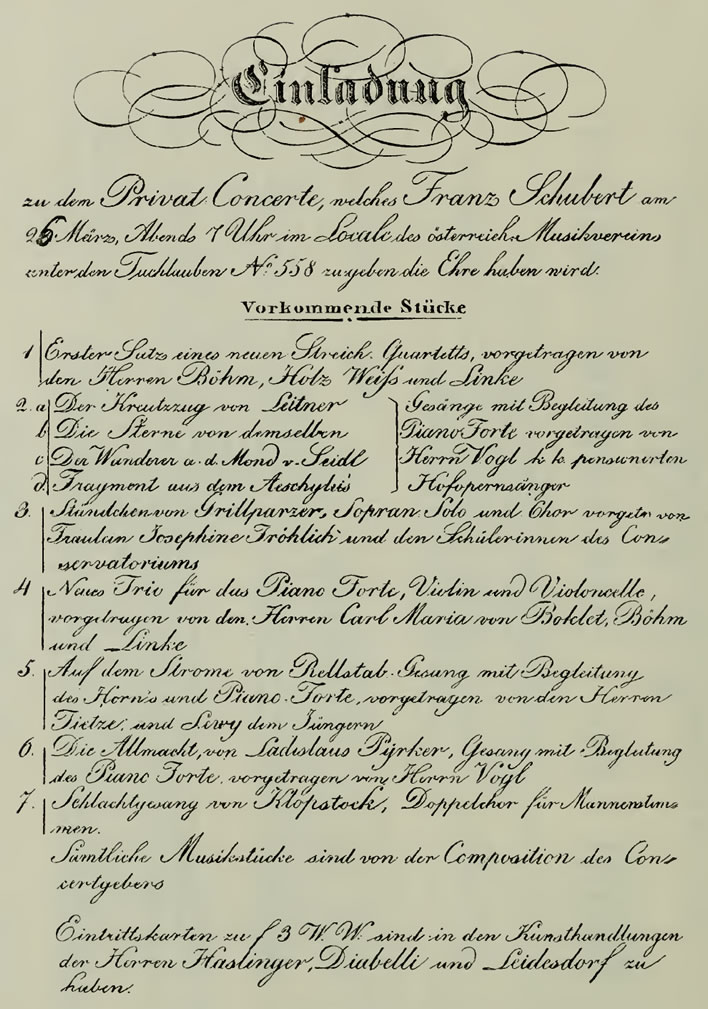

We looked at the Private Concert in some detail nearly two years ago. Here is the combined flyer and programme for the event:

The programme leaflet for Schubert's one and only concert, 26 March 1828.

Schubert musicologists could spend much time discussing this programme – the items that were chosen, the order of their performance and, possibly most importantly of all, the items that were not chosen.

Interesting, for example, is what we might call the 'great gap'. Most of the pieces in the concert belonged to the composer's most recent work, all of them dating from 1826-28. In the midst of this we get an old boiler of Mayrhofer's from 1816, the beginning of Schubert's career, Fragment from Aeschylus (D 450, 1816). Your author cannot begin to comprehend what guided the choice of these pieces.

It is surprising, for example, that the programme has no obviously commercial aims, but then we reflect that Schubert's core income came from selling music to publishers, not to the public. If attending the concert moved someone to purchase a score, Schubert would not be a penny better off for that. Fortunately for our present purposes we can ignore all these puzzles.

After an instrumental opening, the second item on the programme was a group of songs (2a-d) to be performed by Michael Vogl 'singer of the Imperial Court Opera, retired', accompanied at the piano by Schubert himself (although his name was not specified as such here).

What interests us particularly at the moment is the fact that after the concert flyers had been printed, and even after the programme as given here had appeared in newspaper advertisements on 25 March, the programme was changed. Schlechta's Fischerweise was substituted for Seidl's Der Wanderer an dem Mond.

This was a last minute change, but why was it made? What reason was important enough to necessitate sabotaging the printed programme? Such changes when done without obvious reason unsettle audiences.

Your author has no real idea why this dramatic change was made, but can only speculate that, perhaps in a final rehearsal, it became clear to Schubert and Vogl that they had lined up four heavy, gloomy, soulful songs in a single block. That cheerful, uplifting and upbeat piece of Schlechta's Fischerweise was on hand to save the day.

Since we are already pushing the speculative boat out and currently have one foot on land and one on the stern, let us allow ourselves one last push: that it was in fact Vogl who pressed for the change. Vogl knew his audiences and knew what they needed. Schubert had already decided on his programme, so the impulse to change it would probably have had to come from elsewhere. Having been Schubert's house singer for more than a decade, Vogl had the authority that was needed to intervene in Schubert's running order for his own concert. Splash!

Opus 96

Following the March concert we now find ourselves sometime around May or June. Baron von Schönstein and Schubert have received an invitation to perform at a house concert organized by Charlotte Princess Kinsky. Schubert wants to take advantage of this occasion to get Charlotte to accept a dedication to a small album of four songs. But which songs?

Schubert, riffling through the manuscripts in various drawers, came up with Die Sterne (D 939, 1828), Jägers Liebeslied (D 909, 1827), Wandrers Nachtlied (D 768, 1824) and Fischerweise (D 881, 1826), in this order.

Just as with Schubert's selection of the songs for his Private Concert, your author has no explanation for the thought processes that led to this collection of songs. Some texts are diamonds, some texts are stones.

In terms of text quality alone we have two dull stones that should be thrown back into the water, one diamond and one piece of cut glass that is quite pleasant as long as you don't look at it too closely. Schubert's genius could do nothing to rescue the two stones that Schober and Leitner had created – they would sink the greatest musician.

Goethe's diamond had inspired Schubert to place it in a wonderful, crystalline setting. Out of Schlechta's mediocre Fischerweise, as we have seen, Schubert managed to create a song of great charm, despite everything. But in the selection in this album we face that great mystery of Schubert's talent: he shows us again and again what a sensitive reader of poetic texts he is, but nevertheless continues to set rubbish such as Karl Gottfried von Leitner's Die Sterne and Franz von Schober's nonentity, Jägers Liebeslied to music. We'll look at the defencies of these two texts and Schubert's settings thereof another time.

The posthumous narrative

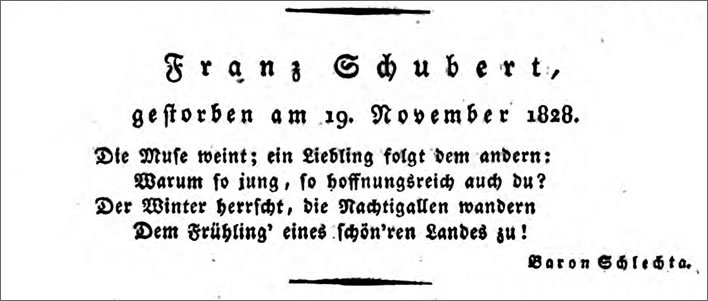

As the bookend which concluded their shared biography, on Schubert's death in 1828 Schlechta wrote a four-line elegy for Schubert, which appeared in the Wiener Zeitschrift für Kunst, Literatur, Theater und Mode on 9 December 1828. [Dok 564]

But as far as we know, Schlechta never wrote a prose obituary or any reminiscence of the Schubert he knew. Whether he was contacted by Schubert's biographers Luib and Kreißle and whether he then responded to such contacts we do not know. Instead of a narrative account of his friend Schubert we are left with only a micro-poem:

Franz Schubert, gestorben am 19. November 1828.

Die Muse weint; ein Liebling folgt dem andern;

Warum so jung, so hoffnungsreich auch du?

Der Winter herrscht, die Nachtigallen wandern

dem Frühling eines schön'ren Landes zu!

Franz Schubert, deceased on 19 November 1828.

The muse weeps; one loved one follows the other;

Why so young, so full of hopes you too?

The winter reigns, the nightingales migrate

to the springtime of a more beautiful country!

Quoted in [Dok 564]. Image: ANNO.

We shake our heads – can this be true? Schlechta has even managed to work his favourite nightingales into his elegy on the passing of Franz Schubert.

According to Otto Deutsch, Anselm Hüttenbrenner set this poem to music in 1861. That song was reproduced in the Viennese magazine Lyra on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of Schubert's birthday on 31 January 1897. There really is no accounting for taste.

Otto Deutsch also adds that Schlechta wrote and declaimed a longer poem about Schubert in 1840, which is now mercifully lost. [Dok 610]

Conclusion

Schlechta the poet, the author of the texts for seven of Schubert's songs, is easy to deal with. We only need to spend enough time in order to fix his place in the canon. We have demonstrated Schubert's rescue of Fischerweise. If you, Reader, want to go searching for pearls in the other six of Schubert's Schlechta songs you are free to do so. Your author, though, has had more than enough of the poet Schlechta to last him a lifetime.

Schlechta the Obscure, the friend of Schubert's, is another matter. He and some other figures on the dark margins of the Schubert biography as we know it today seem to offer interfaces to the wider cultural life of Vienna at the time. A study of these figures would enable us to understand much better the role of that strange creature, the freelance composer, during this period.

Sounds like hard work – perhaps another time.

Sources

All translations ©FoS.

| Dok | Deutsch, Otto Erich, ed. Schubert: Die Dokumente Seines Lebens. Erw. Nachdruck der 2. Aufl. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1996. [DE] |

| Erinn | —, ed. Schubert: Die Erinnerungen Seiner Freunde. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1997. [DE] |

| Konvikt | —, 'Das k. k. Stadtkonvikt zu Schuberts Zeit', Die Quelle, Wien, 1928, Folge 4, p. 477-490. [DE] |

| Dürr | Dürr, Walther, ed. 'Der literarischen Test als Parameter eigenen Rechts: Zur Edition Schübertischer Lieder' in Der Text im musikalischen Werk: Editionsprobleme aus musikwissenschaftlicher und literaturwissenschaftlicher Sicht, Erich Schmidt Verlag, 1998, 416 pages, p. 98-112. [DE] |

| Litschauer | Litschauer, Walburga, ed. Neue Dokumente zum Schubert-Kreis: Dokumente zum Leben der Anna von Revertera, Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag, 1993, Volume 2, 112 pages. [DE] |

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!