Michael Holzer

Richard Law, UTC 2020-07-08 14:24

Anyone who has read only a bit about Franz Peter Schubert has probably come across the name Michael Holzer.

The swots will remember him as the choirmaster of the Lichtental parish church, where Schubert's masses were performed. The swottier swots will add that he was also the person who taught Schubert singing, piano and violin between 1804 and 1809, the period in which he was being prepared for the entrance test for the Imperial Boys' Choir, the passing of which would get him his board and a good education at the expense of the Emperor Franz.

Holzer's rapture over the musical qualities of his pupil Franz Peter was recorded in two memoirs, one by Schubert's father, Franz Theodor, written shortly after his son's death, and one by his brother, Ferdinand, written around ten years later.

There is really only one memoir, for, apropos Holzer, Ferdinand's memoir is an almost word-for-word copy of his father's – yet another example of Ferdinand's lazy and unimaginative curation of his brother's legacy. Ferdinand, who had not an original thought in that wizened, mimetic brain of his; Ferdinand, who could recount an anecdote yet manage to leave out every relevant part.

Writing thirty years after Schubert's death, one of Franz Peter's companions in his Stadtkonvikt days, Anton Holzapfel, passed on to Schubert's would-be biographer Luib one of those frustrating snippets that litter the Schubert sources, snippets which tell us so much, but never enough.

In a masterful phrase – your author is quite filled with envy – Holzapfel mentions almost in passing that Michael Holzer was ein etwas weinseliger, aber gründlicher Kontrapunktist, 'a somewhat tipsy but solid contrapuntist'. [Erinn 72]

Dry humour at its driest and most humorous. To take weinselig, 'tipsy', and gründlich, 'solid' or 'thorough', and apply both adjectives incongruously to that symbol of unimaginative musical drudgery that is so antithetical to the spirit of the limpid songs of the Romantics, the Kontrapunktist – well, that is the mark of a master.

Let's take Holzapfel's cleverly ambiguous barb to mean that Holzer was literally a bit of a bibber, albeit a functioning one. There are so many other adjectives that Holzapfel could have used that we have to take his choice as read. Once we do that, we also understand father Schubert's dry, gimlet-eyed report of Holzer's tear-filled encomium to his talented Franz Peter:

[Michael Holzer] assured me on several occasions, with tears in his eyes, that he had never had such pupil. 'Whenever I wanted to teach him something new', he said, 'he already knew it. As a result I have never actually taught him anything, just talked with him and silently gazed at him in wonder.'

Dieser versicherte mehrmals mit Tränen in den Augen, einen solchen Schüler noch niemals gehabt zu haben. 'Wenn ich ihm etwas Neues beibringen wollte', sagte er, 'hat er es schon gewußt. Folglich habe ich ihm eigentlich keinen Unterricht gegeben, sondern mich mit ihm bloß unterhalten und ihn stillschweigend angestaunt.' [Erinn 244]

If we believe the former magistrate Holzapfel's sly hint about Michael Holzer's fondness for drink we can also recognise Franz Theodor's description of him as barbed satire. Both Anton Holzapfel and Franz Theodor Schubert are indulging in the fine art of that censored era: writing for those reading between the lines.

The proud father Franz Theodor could have easily reported Holzer's admiration for his son's talent without the hysterics, but he didn't, choosing instead to reconstruct twenty years after the fact some direct speech that Holzer said 'on several occasions'. We grim sceptics sense an underlying distaste in Franz Theodor's attitude to Holzer, nine years his junior.

Franz Theodor could not allow himself to be directly critical of Holzer, even several years after Holzer's death – Holzer was after all the man who helped him get his son that important education. But that the Jesuit moralist in him feels it necessary to hint, for those reading between the lines, at Holzer's over-emotional state is a measure of his contempt for this character defect. Dull Ferdinand just copied from his father and thought no more about it, it seems.

Anton Holzapfel is not yet finished giving us food for thought: Holzer, bei dem alle Schubertschen Brüder Musikunterricht nahmen, 'from whom all the Schubert brothers took lessons.'

On the question of whether Holzer taught not just Franz Peter but all the brothers we can take no decision, but it seems not improbable. In fact, in an 1842 piece about Ferdinand, the Allgemeine Wiener Musik-Zeitung asserts that Ferdinand studied singing and then basso continuo and organ with Holzer. But then, why doesn't Franz Theodor – or particularly Ferdinand – mention this, if it was so?

Perhaps it is because in his account, Franz Theodor was writing on the specific point of his grand strategy to get an education for Franz Peter. In this context the musical education of the other brothers was, strictly speaking, beside the point, but even so, it strikes us as odd that Franz Theodor doesn't mention that Michael Holzer was his family's music teacher. Dim Ferdinand, of course, was dimly copying from his father's memoir and never thought to add that he and his brothers had taken lessons from Holzer, too.

If there was frequent contact between Holzer and various members of the Schubert family over more than a decade there is nothing in the documentary record that indicates that Michael Holzer or the members of his family had the same kind of intimate connection with the Schubert family that we find in the case of the Wagners. No mutual godparenting, no witnessing.

Whereas Franz Theodor Schubert and Ignaz Wagner certainly built a long-lasting friendship, we have not the slightest trace of any relationship between Franz Theodor and Michael Holzer that rises above the level of business or acquaintanceship. Given their important positions in the community and Franz Theodor's interest in music, this distance comes as a surprise.

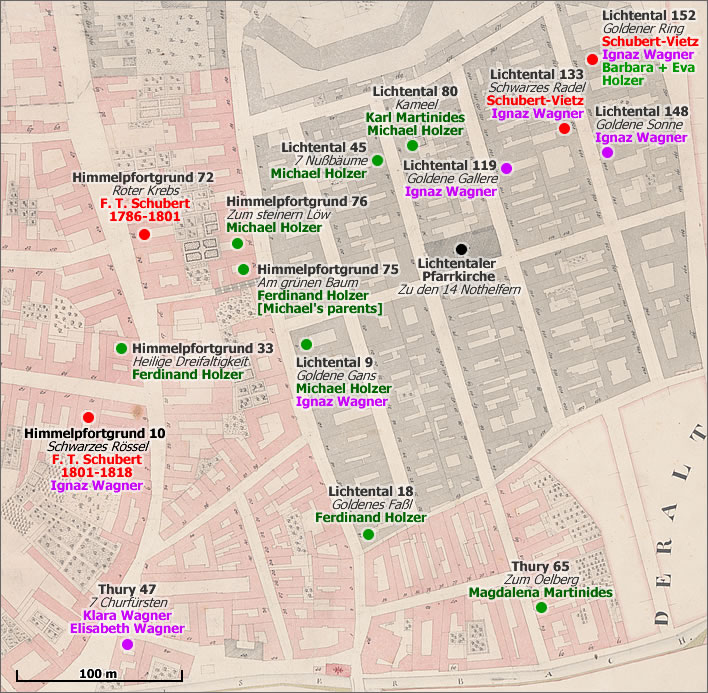

Residences of the Schubert, Wagner and Holzer families 1785~1820. Image: Stadtplan, Anton Behsel (1820-1825), Thury, Lichtenthal 1821. ©ViennaGIS/FoS.

In a tight knit community such as Lichtental there were bound to be many interactions between someone of Franz Theodor's standing and the rest of the community.

On 19 January 1807, for example, during the period that Michael Holzer was still tutoring Franz Peter, Franz Theodor wrote out in his disciplined schoolteacher's hand the will for Magdalena Martinides, the unmarried sister of Karl Martinides, the former choirmaster of Lichtental parish church, and thus Michael Holzer's aunt. She died of tuberculosis exactly one month after the will was signed, so her impending demise would have been foreseen.

Given the stage of the disease, her handwriting would not have been up to the task, either, which is probably why Franz Theodor, the respectable schoolteacher with the elegant handwriting, did the job. He would also have made sure that the formalities of writing a valid will were met and, as a non-beneficiary, was competent to be one of the witnesses (the other was Magdalena's doctor).

The content of the will does not interest us much, except that her niece Anna Maria Holzer-Martinides, wife of Michael Holzer, was one of the two universal beneficiaries who each inherited a modest 81 fl.

Although it is tempting, we should not assume that the writing of this will by Franz Theodor Schubert was a gesture of friendship for Magdalena Martinides. In times before typewriters and word processors, an elegant and disciplined hand was a marketable skill – just one more skill that could earn a bit of money for hard-up teachers. Producing fair copies for money was, however, one further interface with the community in which he lived.

Even if only as a result of Franz Theodor's strategy to get his musical son a good education at the expense of the Emperor, for a number of years Michael Holzer played an important part in the life and education of the young composer and probably the other brothers as well. So what do we know about him?

Artisan's son to choirmaster

Michael Holzer's life is yet another good illustration of the use of the teaching profession as a route to social advancement.

He was born in Vienna on 28 March 1772, the sixth and penultimate child of Ferdinand Michael Holzer and his first wife Rosalia Dreylinger. At the time of their marriage on 19 October 1761 Ferdinand was a journeyman silk stocking weaver, the son of a dyer (or a butcher), and Rosalia was the daughter of a servant. Their witnesses were a chimney sweep and another silk stocking weaver. In later life, Ferdinand Holzer would turn his hand to making wooden clocks.

Michael had two older sisters who survived into adulthood, but all the others in his family of seven died young.

He had the good fortune to receive an education that ultimately qualified him as a school teacher, another one who benefitted from the 1774 school reform which came into force just two years after he was born. How Holzer's education was financed we have no idea.

Just to be clear, Michael was born in 1772 in Lichtental, meaning that Franz Theodor Schubert could have played no part in his elementary education: Michael Holzer was already fourteen and well past elementary school by the time Franz Theodor took over the school in Himmelpfortgrund 72.

Michael also had the good fortune, we are told by one of his children, to have grown up with a violin virtuoso as a neighbour, who gave him the lessons which led to his later musical career.

The defining moment in Michael Holzer's life came on 13 January 1794 with his marriage in Lichtenthal to Anna Maria Martinides.

The marriage record tells us that Michael Holzer was a certified teacher and that the blooming bride was the daughter of the current occupant of the post of choirmaster in Lichtental, Karl Martinides. The witness from the Holzer side was a butcher.

Readers will recall that both Andreas Becker and Karl Schubert married a woman with a school attached. Michael Holzer has now married a woman with a choirmaster's position attached.

The bride's father did his duty and died on 5 November of that year, leaving his job ready to be taken by his new son in law. This seemingly effortless transfer is misleading: such para-religious posts in the Empire of Paperwork could not simply be handed down from father-in-law to son-in-law – Michael would have had to prove his suitability for the job and to have had an array of fixers and backers on his side.

Michael's bride was blooming in the same way that Franz Theodor's bride had bloomed at their hasty wedding: a daughter, Elisabeth, arrived only four months later on 8 May that year. She survived just over a year, so one further, grim commonality.

Whilst on that point we note that the Holzer's breeding record was much better than that of the two Schubert families or the Wagner family: out of five children, only two infant deaths and three children who lived to old age.

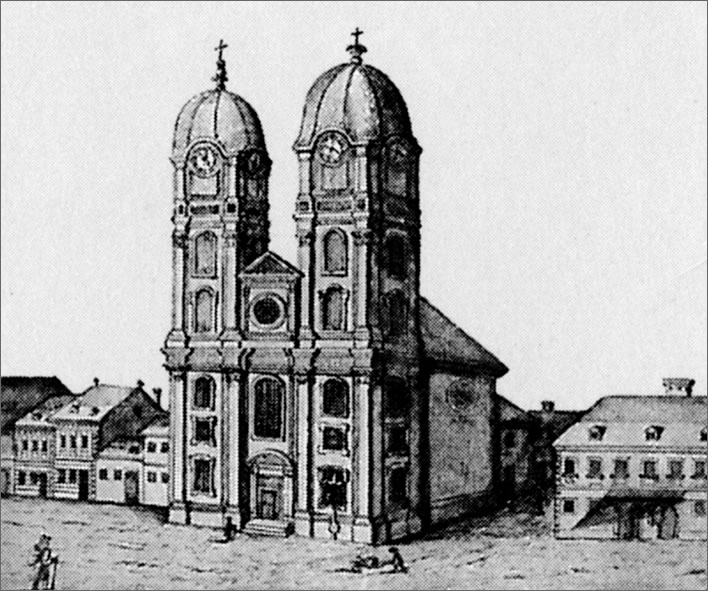

Lichtental Parish Church. Artist and date unknown.

Choirmaster to down and out

Michael Holzer died of Magenverhärtung, probably stomach cancer, in Himmelpfortgrund 76 on 23 April 1826, having just turned 54. He died destitute, possessing nothing worth recording – even his few clothes, der wenigen schlechten nicht schätzenswerthen Leibskleidung, were not even worth the effort of valuation. He was buried at the cost of the parish of Lichtental. He left three children and a penniless widow.

He seems to have been plagued by a shortage of cash, which started in earnest in 1806 – in the middle of the period 1804-1808, in which Holzer was instructing Franz Peter Schubert in preparation for his entry exam for the Imperial Boys' Choir.

We know this because in 1802, Hölzer had signed up to the Tonkünstler-Societät, the 'Musicians' Society', a benevolent organization set up to provide pensions for the widows and orphans of its members.

The access to a pension was one of the great material benefits of that uncertain age, since without one of these only penury and starvation or cold charity awaited dependents. If we ever wonder why so many creative artists laboured on for years in the civil service we should always think first: pension!

In the Musicians' Society, members paid into the fund and on their deaths their widows received a pension of 200 fl (C.M.) – not much, but at least better than the minimum wage for a school teacher and a good actuarial gamble if the musician died young.

As the years went by after 1802, Holzer repeatedly came into arrears for his contributions, until 1812, when the Society finally excluded him for unpaid fees. The amount owing was trivial, just under 17 fl. (W.W.), giving us an indication of just how broke he must have been if he was unable to raise that sum. [NB: the value of the W.W., the Wiener Währung, varied between one-half and one-quarter of the C.M., the Conventions Münze.] His financial situation never improved, for at his death 14 years later even the clothes off his back were not worth selling. Why was he so poor?

To answer that question, we should return to the Jesuitical examples of the two Schubert brothers, Franz Theodor and Karl.

The life lesson they teach us is that, though starting with a small fixed income, it was possible to make money in Vienna. The key to doing this was dedication, years of industrious drudgery, taking on extra paying work wherever this was available, seizing whatever chances turned up and leading a moderate, self-disciplined and abstemious lifestyle. Franz Theodor's anxieties for his son Franz Peter's future as a buccaneering freelance composer arise from this perception: the only way out of the swamp was an iron work ethic combined with a sober and even ascetic life.

Holzapfel's weinselig, 'tipsy', jibe may hint at one defect in Holzer's life. One might think that it would have been easy for the choirmaster of the parish church to acquire private students in music-mad Vienna. It appears that the Schuberts were customers of his, but who else? Was he lazy? Did his old-fashioned musical understanding not appeal to his students? Once his weinselige behaviour became apparent, did his pupils stick with him? Who knows?

His predecessor, his father-in-law Karl Martinides, was nearly as destitute when he died in 1794. At least he was able to leave enough shabby furniture to fill a shabby bed-sit.

As we suggested earlier, we might imagine that in Holzer the gimlet eye of Franz Theodor saw a man who was slithering down the slope into indolent, boozy poverty whilst he himself was labouring up the slippery slope of financial success and social esteem. Holzer seems to have been a man with a personality that was almost the opposite of Franz Theodor's. Who knows?

However speculative, this would be one explanation for the arm's length treatment of Holzer in the Schubert record.

Michael Holzer and Laibach

Since this flight of fancy has already taken us higher than it should, we may as well give a few more flaps and melt the wax properly.

What role, if any, did Michael Holzer play in the 1816 drama surrounding Franz Peter's application for the post of Music Teacher in the newly founded music school in Laibach (Ljubljana in present day Slovenia)?

The post offered a modest salary of 500 fl. per annum. Schubert's father was paying him 80 fl. a year as an assistant teacher, which makes the 500 fl. from Laibach seem like a fortune. Franz Peter's teacher's salary works out at just over 13 Kreuzer a day, which is less than was spent to feed the average inmate of a dungeon at the time.

But, put in context, the situation is quite different. Otto Deutsch calculated that, averaged over his lifetime of musical buccaneering, Schubert earned 750 fl. a year. The Laibach position was nothing special: the salary was comparable with other mid-range musical posts in Vienna. The only advantage of the post was that it would have been a steady income and the position would have allowed him to marry. But then, whilst the buccaneer could choose to live cheaply in Viennese hovels or doss down with friends, the married man would have had greatly increased costs to maintain the decorum required of the post.

We are surprised that Franz Peter even applied for this post, 250 tedious kilometres from his beloved Vienna, but his situation at the time was a mess and he did not have the advantage of our hindsight.

The selection procedure took around three months, from the mid-May to mid-August. There were 21 applicants for the post. It was only after the first round of the procedure that Salieri (who was involved in the selection process) suggested Schubert apply. Holzer, an insignificant choirmaster, played no direct part in Schubert's application.

Franz Peter was slaving as an assistant teacher for his father in Himmelpfortgrund on subsistence pay and desperately attempting to detach himself from that drudgery. Worse still, his father had effectively committed him along with his other sons to taking a post in the new school at Rossau, which was then under construction. The new school would become the family firm, in other words. An eternity of school teaching stretched ahead of him.

Freeing himself from that would lead to yet another battle with his father, but his father could hardly object if he got a steady job such as that in Laibach. It would, after all, be a fixed position that would even allow him to marry his beloved Therese Grob. In such turmoil no one thinks straight, let alone a teenager, so it was great good fortune that those offering the post chose someone else.

During this year of Sturm und Drang Schubert took to keeping a journal. Deeply introverted, he was not a natural diarist and the thoughts he set down are vague musings that have almost no interest for even the most passionate Schubert fan. Schubert was psychologically incapable of revealing his life and his thoughts in plain language.

If we can trust the general absence of documentary records of diary keeping in the Schubert biography, it seems clear that Schubert gave up the practice of journal keeping not long after he started. In later life he occasionally entrusted brief thoughts to paper or attempted literary excursions such as Mein Traum (03.07.1822 Dok 158f.) but, trapped within his introverted brain, no sense is to be had from them.

Yes, yes, you say… but what has this got to do with Michael Holzer?

We must be clear that Franz Peter's contact with Michael Holzer did not end when he entered the Stadtkonvikt and Academic Gymnasium in October of 1809. He left the school in September 1813 and began his one year teacher training course at the Normalschule Sankt Anna in November. He completed the course and passed his final exam on 19 August 1814.

From September onwards for approximately the next three years, he was an Assistant Teacher in his father's school in Himmelpfortgrund 10. During those three years he was an active visitor to the church choir in the Lichtental parish church. Franz Peter, the workaholic son of a workaholic father, spent those years not only churning out hundreds of secular song compositions – among them some of his greatest – but also knocking off not insignificant pieces of church music.

The most notable of these is the F Major Mass D 105, first performed on 25 September 1814 in Lichtental and a few days later in the Augustinerkirche in Vienna. This was followed by numerous smaller pieces and also three more masses for the Lichtental church. The last of these, the C Major Mass D 452 is dated between June and July 1816 and is dedicated to 'Hr. Holzer', a dedication that was expanded when the mass was published in September 1825, a year before Holzer's death. In 1816 Schubert also dedicated his Tantum ergo D 460 to 'Hr. Holzer'.

Well, of course, Franz Peter was not just haunting the rococo alcoves of the Lichtental church on his rare days off from teaching just for church music and cosy, though moist-eyed chats with the choirmaster. There was the heavenly soprano of his Therese Grob which soared above it all.

Unfortunately, the pathologically inhibited composer never quite got around to telling Miss Grob that she was 'his Therese' and she ended up being kneaded in the yeasty hands of a master baker, completely oblivious – so she wrote later – of the rapidly beating heart of the quiet genius who worshipped her.

The three-month crisis around the application for and ultimate rejection of the Laibach job, which in turn led to his ultimate rejection of a fixed position in favour of musical freebooting, fell in this period. In effect, Franz Peter's concept of his musical and financial future was forged at this moment.

In 1816 Schubert was nineteen. He must have been aware of the decrepit financial and moral state of his former teacher, that 'somewhat tipsy but solid contrapuntist', bobbing in that backwater of church music and private lessons – a fate quite sufficient to drive anyone to drink.

In contrast, Schubert the genius was creating the new music for his time, not decorating fustian and stitching together musty brocade. By the end of 1816 the 19-year-old had created around 500 Lieder and in doing so reinvented the Kunstlied and earned the title which subsequent generations would know him by, the Liederfürst, the 'Prince of Song'. The years 1815 and 1816 would become known as Schubert's great Liederjahre, 'song years'.

After he was rejected for Laibach, he never applied for another job again. We and he must kiss the ground and thank the heavenly powers that he never even made the final selection for that job.

Indeed, those powers seem to have been sending him signals from that moment on. He noted in his journal on 17 June 1816 that he had done his first 'composition for money' for which he had received 200 fl. (W.W.). In 1818 he spent the summer and autumn months as a paid music master with the Esterházy family in Zseliz. He reported to his brother Ferdinand in August 1818 that he had earned 200 fl. for the preceding month, including his travel costs. We chomp at our pencils: that's around twice what his father was paying him for a year of schoolteaching! [Dok 64]

In 1819 it seems he made the final break with his father from his schoolteaching duties in the family firm. He was supposed to return to his teaching duties in Rossau in 1819, but it appears from the fragment of a torn up application (from 1819?) [Dok 81] for a return to his teaching job that the moment of separation and the start of his freelance career had come. And, apart from a few brief wobbles, it had.

Michael Holzer, the ghost of what might have been, continued to scratch what he could of a living until his death in penury in 1826. The teaching trio, Franz Theodor, Ignaz and Ferdinand, continued their drudgery to attain solid respectability. Therese Grob brought more closure in November 1820 by marrying Johann Bergmann, the master baker.

Franz Peter acquired his own baritone singer, Johann Michael Vogl, along with young friends with bright ideas who talked of the sublime in art, who drew portraits and wrote poetry and talked and played music and danced and sang.

Choirmaster? Director of Music? Solid contrapuntist? Ha, phooey!

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!