The family bond

Richard Law, UTC 2020-07-08 14:24

Happy families

A sketch by Carl Schubert, Franz Peter's painter brother, of a scene of family life among the Schuberts (in 1822?). Franz Theodor is seated in the centre. The figure standing on the left at the back is either Ignaz or Ferdinand Schubert. In front of him is Franz Peter. The female group on the right consists of Anna Schubert, Franz Theodor's second wife, who is holding Carl's son Heinrich. The figure on the extreme right is that of the maid 'Margarethl'.

This charming sketch shows us the happy coexistence within Franz Theodor's second family.

His first wife Elisabeth Vietz died on 28 May 1812, leaving the four brothers Ignaz (27), Ferdinand Lukas (17), Franz Karl (16) and Franz Peter (15) and their sister Maria Theresia (10).

Eleven months later, on 25 April 1813, he married the 29 year-old Anna Kleyenböck. There is reason to believe that the Grobs were the matchmakers, since Anna also came from a prosperous silk-weaving family.

The youngish wife – barely older than the oldest brother, Ignaz – seems to have energised the 50 year-old Franz Theodor and it wasn't long before more babies appeared: Maria Barbara Anna (1814), Josefa Theresia (1815), Theodor Kajetan Anton (1815-1817) – then after a rest to get his breath back, Andreas Theodor (1823) and finally Anton Eduard (1826).

Unlike the experience in his first family, nearly all of these new babies survived infancy, which might suggest better health in the well-heeled circumstances of the Rossau school – or suggest perhaps nothing of the sort.

Anna Kleyenböck integrated well into the existing Schubert family and seems to have been treated with respect and affection by the children of the previous marriage.

Relatives, friends and neighbours

The greatest insight by far into the dynamics of the Schubert family and the local community comes in Franz Peter's correspondence with his brothers during the summer months he spent with the Esterházy family in Zseliz in 1818. Franz Peter had never really been away from Vienna before that. These letters contain almost the only insight into his family life that we possess.

Ignaz Schubert and the Hollpeins

Let's begin by looking at some parts of a long letter which Ignaz Schubert wrote to his brother in Zseliz on 12 October 1818.

… The name day of our Papa was marked with a celebration. The entire staff of the Rossau school with wives, brother Ferdinand and wife, our aunt and Lenchen and the entire clan from Gumpendorf were invited to an evening party, at which we valiantly ate and drank and which was very merry.

… Das Namensfest unseres Herrn Papa wurde feierlich begangen. Das ganze Rossauer Schulpersonal samt Frauen, der Bruder Ferdinand samt Frau, nebst unserm Mühmchen und Lenchen und der ganzen Gumpendorfer Sippschaft wurden zu einem Abendzirkel eingeladen, wo wacker geschmauset und getrunken wurde und es überhaupt sehr lustig herging. [Dok 71]

Franz Theodor and his family had only just moved to the newly rebuilt school in Rossau at the end of 1817, so it would be interesting to know who comprised the 'entire staff of the Rossau school with wives'. By 'our aunt' is meant, of course, Magdalena Schubert-Vietz, Karl Schubert's widow. It is unclear for the moment whether at this time she was still residing in Himmelpfortgrund 10 or had already moved to her new residence in Rossau 28, where she ran the girls' school.

'Lenchen' is the nickname of Magdalena's daughter Maria Magdalena (1797-1859). She was at that moment 21 years-old. The specific way Ignaz refers to Lenchen hints at her standing in the family. She is almost exactly the same age as Franz Peter and was thus his natural childhood companion. She was a year older than Therese Grob. The three children – Franz Peter, Lenchen and Therese Grob – grew up side by side and would have attended classes in Franz Theodor's school at about the same time.

The 'entire clan from Gumpendorf' refers to the relatives of Anna Schubert-Kleyenböck, who came from Gumpendorf, a suburb near the centre of Vienna. Her marriage to Franz Theodor is now five years old and the social matrix which Anna brought with her into the marriage is clearly still flourishing and well integrated in both directions.

Ignaz continues his letter with some news about friends and relatives:

Now a few words from the Hollpeins. Both the husband and the wife send their heartfelt greetings and ask whether you think of them from time to time? They would like to see again soon, although they think that your new social relationships may keep you away. They regret this frequently, since they love you, as we all do, with the most sincere heart and talk frequently of your happy condition with the sincerest sympathy.

Nun auch ein paar Worte von den Hollpeinschen. Sowohl Mann als Frau lassen Dich herzlich grüßen und fragen, ob Du denn auch bisweilen auf sie denkest? Sie wünschten, Dich bald wieder zu sehen, wiewohl sie meinen, Du werdest bei Deiner Rückkehr nach Wien nicht so häufig mit Deinen Besuchen sein, wie sonst, da Dich Deine ganz neuen Verhältnisse wohl davon abhalten möchten. Dieses bedauern sie gar oft, denn sie lieben Dich, so wie uns alle, mit dem aufrichtigsten Herzen und äußern oft über Deine glückliche Lage die innigste Teilnahme. [Dok 71]

The 'Hollpeins' were the coin engraver Leopold Hollpein (1785–1836) and his wife Wilhelmine Grob (1785-1856). Yes, that Wilhelmine, the daughter from Bartholomäus Grob's first marriage. They had married on 23 December 1807 in Lichtental. He was 23 and she was 22 years old. They lived at Lichtental 147, very close to the Grob family residence of Lichtental 163.

They had four children, three of whom survived infancy: Therese (1808-1848), Heinrich (1814-1888) and Karl (1818-1875). Heinrich Hollpein would achieve fame as a portraitist and writer. Ignaz's letter is dated 12 October 1818, meaning that Karl Hollpein, who had been born on 23 April, was just six months old at the time.

We relish Wiener Schmäh – that ironic and cynical humour of the driest type – wherever we find it. Here we are party to a fine example between Ignaz and Franz Peter. Mocking his brother's currently elevated social company – that is, the Esterházys in their country house of Zseliz – Ignaz portrays the Hollpeins wondering whether Franz Peter will ever be able to bring himself to socialise with them ever again.

Whether the mockery has been cooked up by Ignaz or Leopold or both of them we don't know. Whoever it was, it was a fine example of the genre, for it concludes with the massive sarcasm that only true intimates can afford to wield against each other: 'They regret this frequently, since they love you, as we all do, with the most sincere heart and talk frequently of your happy condition with the sincerest sympathy'.

Those readers who remember our discussion of the anticlericalism (Bonzenheer, 'army of clerics') shared by both Franz Peter and Ignaz will not be surprised to find that Ignaz's mockery of the elevated society his brother is currently keeping shows clearly that he is generally chippy about all his betters, whether clerical or secular.

Ignaz's particular mention of the Hollpein family brings one further facet of the extensive integration there was between the Schubert family and the various Grob families. That it should be Ignaz who brings the Hollpeins into the letter in itself has some significance.

Leopold Hollpein would die on 24 Februar 1836 as a result of an 'accidental fall' (according to the Wiener Zeitung for 12 March 1836). With Leopold out of the way his widow Wilhelmine and Ignaz didn't hang around: they married on 14 September 1836. They were then both around 51 years old.

An 'accidental fall', indeed! We know from another example of Wiener Schmäh, this time in a letter from Franz Peter in Steyr to his parents in Vienna dated 25 July 1825, that Ignaz's interest in the Hollpeins was not just present in 1818, but was even more present in 1825:

Ignaz will probably be at the Hollpeins at the moment; since he is only there mornings, afternoons and evenings, it would be difficult for him to be at home. I cannot cease to marvel at his endurance, although one doesn't really know whether it is actually a benefit or not, whether he is more deserving of Heaven or Hell. He will have to explain it to me.

Ignaz wird vermuthlich jetzt eben bei Hollpein sein; denn da er nur Morgens, Nachmittags und Abends dort ist, so wird er schwerlich zu Hause sein. Ich kann nicht aufhören, seine Ausdauer zu bewundern, nur weiß man nicht recht, ob es eigentlich ein Verdienst ist oder keines, ob er sich dadurch mehr den Himmel oder die Hölle verdient. Er möchte mich doch darüber aufklären. [Dok 300]

By 1836, in Ignaz's slow way, he would finally get the girl. Franz Peter may have let his Grob slip away in 1816, but his oldest brother got one in the end, even though he had to wait twenty years – perhaps even thirty if he had started spooking around them straight after their wedding in 1807. 'Everything comes to him who waits'. Only another ten years to go, Ignaz!

Ignaz would have been writing his letter to Franz Peter in his room at the Rossau school, so it is natural that he concludes the letter by sending greetings from the important women in Rossau:

The aunt and Lenchen also send their heartfelt greetings.

Das Mühmchen samt Lenchen lassen Dich ebenfalls herzlich grüßen. [Dok 71f]

From this greeting we can now assume that Magdalena Schubert-Vietz and her daughter Magdalena did in fact move to Rossau at the same time as Franz Theodor moved his school there.

Ferdinand Schubert and Therese Grob

Ferdinand Schubert also wrote to Franz Peter in Zseliz sometime in mid-October 1818. Ferdinand had had a teaching post in the orphans' school since 1811 and at the time of writing is heavily involved in his Director's attempt to introduce new educational techniques – easier to do in the orphanage school, where there were no parents to object to the innovations.

Our good father told me that even your little sisters, Marie and Bebi [=Pepi=Josepha] are getting tired of your absence and ask daily: when is Franz coming?

Unser guter Vater sagte mir, daß sogar Deinen kleinen Schwestern (Marie und Bebi) die Zeit schon lang wird, und täglich sich erkundigen: Wann kommt denn einmal der Franz? [Dok 72]

Marie [Maria Barbara Anna *1814] and Josepha [Josefa Theresia *1815] are the oldest children of Franz Theodor's new family with Anna Kleyenböck. At the time this was written the third child, Theodor Kajetan Anton (1815-1817) had died the previous year. Two more sons were still to come. This is another indication of the good integration between the two Schubert families.

Since Ferdinand's focus is the orphanage at which he teaches we hear much of his musical doings there. Amongst all this gossip our attention is suddenly captured when the name Therese Grob pops up.

We learn that Ferdinand had tried to organize a celebration of the name-day of the director of the institution, the educationalist Franz Michael Vierthaler [name-day: Archangel Michael, 29 September]. We are impressed by Ferdinand's honesty in describing this musical disaster, but his brother must know his talents – or lack of them – by now:

I wanted to celebrate the name-day of our Director with a big concert. Since I was lacking singers and money, it turned into a small concert. The entire orchestra consisted of thirteen members (strings, oboe and horn). Therese Grob refused to sing – she just wanted to be in the audience on this occasion.

Das Namensfest unseres Direktors wollte ich mit einer großen Musik feiern. Allein da es mir an Sängern und Finanzen fehlt, wurde eine sehr kleine daraus. Das ganze Orchester, welches außer den Geigen-Instrumenten nur mit Oboen u. Corno besetzt war, bestand aus 13 Individuen. Die Grob Theres schlug mir den Gesang ab; sie wollte diesmal bloß Zuhörerin sein. [Dok 73]

This is Ferdinand Schubert writing, so we can expect that his opaque prose will frustrate us more than it illuminates us. Among all the other unnamed actors in his account, why does he mention Therese Grob by name? Was this an acknowledgement of her special meaning for his brother Franz Peter?

But then, reading the flat wording of this letter, we wonder whether Ferdinand at this time had any idea of the emotions that must have churned in his brother's heart at the mention of the girl with the beautiful soprano.

Or perhaps not, for in Zseliz Franz Peter had found two empathetic females – ein Paar wirklich braver Mädchen 'a couple of really good girls', one of whom became his current love interest Pepi Pöcklhofer. It is a truth universally acknowledged, that the best cure for an old love is a new one – the hair of the dog, as it were.

Though we blame Franz Peter's introversion for his failure to get somewhere with Therese Grob, in 1816 she was a well-brought up 18 year old, chaste in mind and body, who probably lacked the maturity to deal with men – and particularly shy men – confidently. She may have been as introverted as he was for all we know. Unless the families stepped in, this pair of lovebirds would remain silent for ever – and silence was what in fact happened.

In Zseliz, on the other hand, it appears from Franz Peter's expressions of warmth towards the 'good girls' that he was with two girls who knew how to talk to a man: the chambermaid Josepha 'Pepi' Pöcklhofer was almost exactly the same age as Franz Peter; the lady's maid Therese Tschekal a few years older. Pepi would take over Therese's job shortly after this.

She certainly impressed Franz Theodor when he met her briefly in 1824. Unlike Theresa Grob, who was footling around in a rich family waiting for a husband to turn up, Pepi and Therese were two respectable working girls who had their own careers, careers which required above everything else the ability to empathise with others. The respectful deference coupled with charm that we imagine pleased the crusty old teacher Franz Theodor was part of the job description.

Figaro may be the eponymous scheming genius of Le nozze di Figaro but it is his bride, the lady's maid Susanna, who has the emotional intelligence to see into the minds of Count Almaviva et al.

Franz Peter's last letter that we have from Zseliz was addressed to his siblings Ferdinand, Ignaz and Theresia and dated 29 October 1818.

Firstly he sends greetings to the two step-sisters who were missing him so much:

Greet and kiss the lovely little creatures Pepi and Marie for me, as well as my good parents.

Die lieben kleinen Geschöpfe, Pepi und Marie, grüße und küsse mir herzlich, so auch meine guten Altern.[Dok 74]

He closes with more greetings and some responses to points in the letters they have sent him.

Whether you thought of me during the feasting, I don't know.

—Ob ihr bey der Schmauserei an mich dachtet, weiß ich nicht. [Dok 75]

Franz Peter is having some fun with Ignaz's description of the feasting on the occasion of their father's name-day. Whereas Ignaz piously asserts that the revellers missed Franz Peter's presence when they were making music, Franz Peter, with a reputation as someone who likes his food, self-mockingly wonders whether they perhaps thought of him during the feasting itself.

And you, dear Resi, think often of me, that is charming.

Und du, liebe Resi, denkst oft an mich, das ist charmant. [ibid]

Since this letter is addressed to the siblings Ferdinand, Ignaz and Theresia (his little sister, now 17 years-old), du, liebe Resi, 'you, dear Resi' means that Theresia. Otto Deutsch states that Theresia sent a letter to Franz Peter enclosed with Ignaz Schubert's letter dated 12 October 1818, so we must assume that 'you, dear Resi, think often of me' is a direct response to some statement in the missing letter.

I send 99 kisses to all the Hollpeins, man and wife, and Resi and Heinrich and Karl, also his godfather together with his future wife.

Die Hollpeinischen, sowohl Mann als Frau u. Resi u. Heinrich u. Carl u. seinen Herrn Pathen, samt zukünftiger Gemahlin laß ich alle 99 Mahl küssen. [ibid]

Then Franz Peter picks up Ignaz's Schmäh (alleged to be from the Hollpeins) suggesting that he will be too good for them now, but decides to make no more of it in writing.

'Resi' and 'Heinrich' and 'Carl' are, as in Ignaz's letter, the Hollpein's children. 'Carl's godfather' is a roundabout way of sending greetings to Carl Schubert, the artist brother, who was about to be married to Therese Schwemminger.

This statement is a little puzzling, since Carl Schubert did not marry Therese Schwemminger until five years later on 19 November 1823 in Lichtental parish church. The process required for the marriage to be permitted under the Ehe-Consens law was started a little over a month before on 6 October 1823. Were Carl and Therese really engaged for five years?

The family bond

Whatever disagreements Franz Peter had with his father over his buccaneering profession as a freelance composer, the bond within the family survived them. The ties that bound the family together were forged in the cramped proximity of life in the teeming schools of Himmelpfortgrund and they remained with them throughout their lives.

One final example of those ties comes in 1828, ten years after Franz Theodor and his teacher sons had moved to the school in Rossau, ten years after that first visit to Zseliz and ten years after Franz Peter had started out on his wilful, buccaneering life.

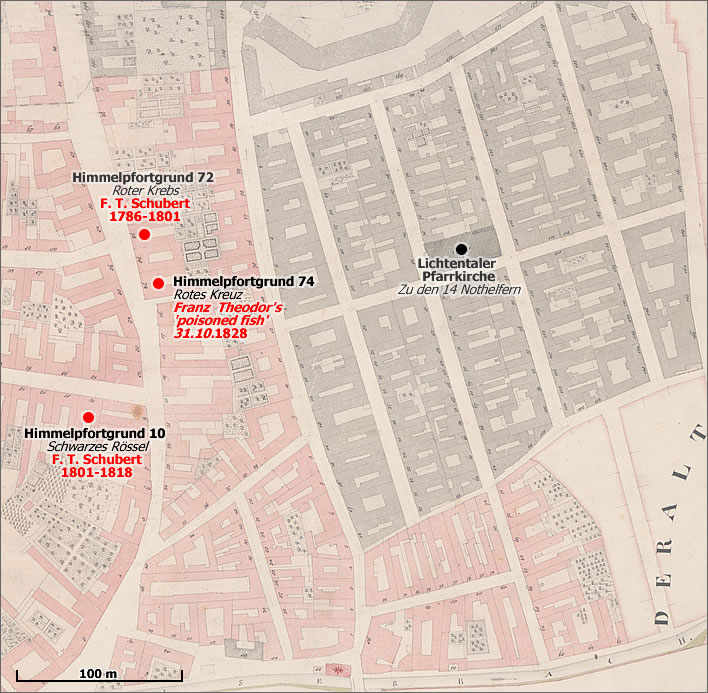

We find the family together once again in Himmelpfortgrund on 31 October, presumably for the Feast of All Saints (1 November) or All Souls (2 November). The two important feast days are frequently run together for the tradition of remembering the souls of the dead and for visiting and decorating the graves.

A pious and close family such as the Schuberts would certainly observe this day – it would have been shameful had they not done so. They have ten dead children to remember, the first wife and mother, Elisabeth (†1812), the seven dead children from brother Karl (†1804) and Magdalena, the infant Theodor Kajetan Anton from the second marriage and the ancestors from distant Moravia.

Ten years after the core Schubert family had moved to Rossau and Franz Peter, Ferdinand and Carl were all living elsewhere, we learn that at least Ferdinand and Franz Peter (who was staying with Ferdinand at the time) walked the 5 km from Ferdinand's apartment in Neu-Wieden, to the Gasthaus 'zum roten Kreuz' in Himmelpfortgrund.

The family reunion in Zum roten Kreuz, with the 'poisoned fish'. Image: Stadtplan, Anton Behsel (1820-1825), Thury, Lichtenthal 1821. ©ViennaGIS/FoS.

We can only presume that they must have both gone to meet other family members there, but, as usual, Ferdinand's account frustratingly leaves out all the relevant material. We know from a letter which Franz Peter wrote to his parents from Steyr on 25 July 1825 that Ferdinand was especially loyal to that restaurant. According to Otto Deutsch, however, Franz Peter thought it served adulterated wine:

He probably still crawls to the Kreuz and cannot be rid of Dornbach; he will certainly be ill again seventy-seven times and will think he is dying nine times, dying as though it were the worst thing that could happen to a human.

Er kriecht vermuthlich noch immer zum Kreuz und kann Dornbach nicht los werden; auch wird er gewiß schon wieder 77 Mal krank gewesen zu sein, und 9 Mal sterben zu müssen geglaubt haben, als wenn das Sterben das Schlimmste wäre, was uns Menschen begegnen könnte. [Dok 300]

It seems a strange thing for Franz Peter to do, to go five kilometres with Ferdinand to a restaurant he disliked for a meal on All Souls Day, unless it was a family event for this solemn feast day.

It was there that Franz Peter ate the fish the taste of which, according to Ferdinand, so revolted him that he left it uneaten, believing it to have been poisoned. Schubert chose to eat fish because 31 October 1828 was a Friday, a day of meat abstinence for Catholics.

Perhaps his low opinion of the Kreuz informed his persistent hypochondria and predisposed him to blame the fish from that restaurant. What those present on that occasion did not know was that his premonition was justified: in less than three weeks, Franz Peter himself would join the company of all silent souls.

This last act of familial piety is a fitting conclusion to the span of a life that was lived, however strong the centrifugal forces of the composer's metropolitan life were, in the intimate context of the family in the wider social context of the communities of Himmelpfortgrund and Lichtental.

0 Comments

Server date and time:

Browser date and time:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!