The female factor

Richard Law, UTC 2020-07-08 14:24

One clear lesson that we can take from our extended look at the community in which Franz Peter grew up is that the social network in that community consists of both male and female links – how could it be otherwise? In fact, we might even assume that the girls and women of the district were much better than the men at establishing and cultivating social connections.

We ethnographers, currently observing the tribes in that distant country called the past, know that if we really want to understand the things that are done so differently there, we must seek out the females of the tribes, for it is they who hold it all together.

Unfortunately, it is just those female networks about which we know so little.

Tetchy feminists might feel that this paucity of information is due to the lack of interest of the predominantly(?) male reseachers in this field, but the reason is more likely to be that the documentary records of the time were not really concerned with females beyond the laconic information contained in birth, marriage, death and testamentary records.

From these miserable pickings it is just possible to gain a hint, if no more than that, of the female network which included the Schuberts. One of the keys to this insight comes from the establishment by Maria Theresia's Schulordnung of 1774 of girls' schools.

Girls' schools

Before readers leap up and down in excitement at this innovation, they should be aware from the outset that this was half-hearted stuff. Girls were just as much obliged at boys to attend a Trivialschule, but boys and girls had to sit on separate benches – which is what would have happened in Franz Theodor's schools in Himmelpfortgrund as far as we know.

Where possible – the Schulordnung puts it no more strongly than that – a separate school for girls should be established. These schools were to instruct the girls in 'sewing, knitting and other things appropriate to their sex'. Where there was no separate girls' school, a similar educational diet was to be served up for the girls in mixed sex schools. On the details of exactly how this was to be implemented, which 'boy subjects' were to be skipped in favour of which 'girl subjects', the Schulordnung is vague.

Two centuries on, readers may find the intellect-free female role imagined by the Schulordnung to be horribly constricted, but that was how it was.

Looking on the bright side – our preferred viewpoint on this website – we are cheered that the education of girls was just as obligatory as that of boys. Girls were taught religion and the three Rs just as the boys were, but ultimately, girls were prepared for the roles generally available to them at that period – it would have been a poor education system that prepared them for lives they would never be required to lead.

And – still looking on the bright side – the explosion in the quantity of magazines and almanacs primarily intended for a female readership that took place in German-speaking countries in the 19th century was detonated by the new universal female literacy that had been introduced by the educators of the late 18th century in Austria, Germany and Switzerland.

The 'girl subjects' were to be taught by women who had qualified for this role. Their abilities in these subjects had to be certified by Ursulines, the members of the Order of Saint Ursula.

David Adolph Constant Artz, Interior of the Katwijk Orphanage, c1870-80 (detail).

To this end, the girls' school set up by the order became a kind of Normalschule that was used as the measure for all the others.

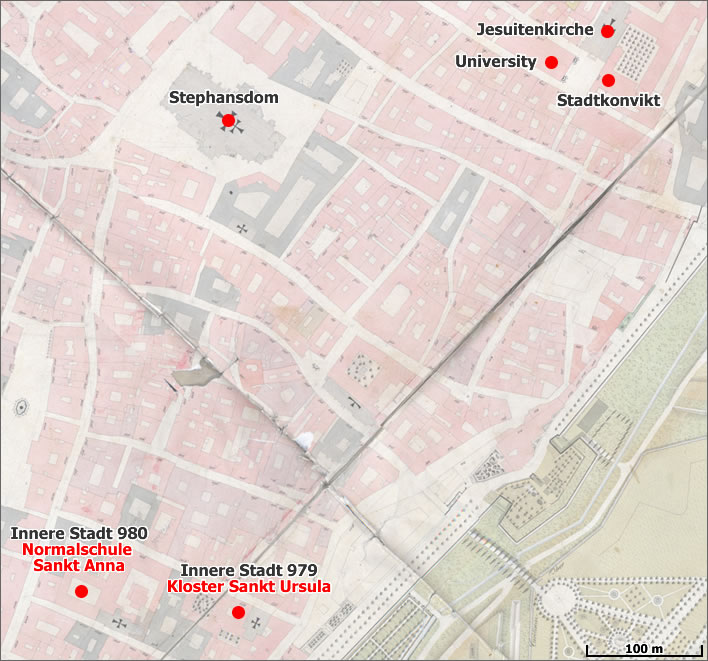

The Normalschule for Vienna, Saint Anna, which started the teaching careers of all the Schuberts, next to it was the Convent of Saint Ursula, which was responsible for the assessment of teachers for girls' classes. Image: Stadtplan, Anton Behsel (1820-1825), Innere Stadt 1824. ©ViennaGIS/FoS.

Magdalena, Magdalena and Therese Schubert

It appears to be the case that in each of the two Schubert schools in Himmelpfortgrund, at least one qualified female teacher had to have been available. Unfortunately, the relevant records for most of this period have been destroyed.

The first hint we get of who these teachers were is an entry in the diocesan archive (it was the job of the church diocese to supervise the schools) which relates to the school at Himmelpfortgrund 10 and which is dated 14 February 1814.

The entry tells us that Franz Theodor Schubert had submitted a list of persons who teach 'female work' in the school and requested that they be tested by the Ursulines and given 'permission to continue teaching girls'. Unfortunately the names submitted on that list are unknown. However, on 17 March 1814, we learn that a 'Magdalena Schubert' had been tested and accredited as a girls' teacher.

Which 'Magdalena Schubert' is meant here is uncertain. The most probable person would be Magdalena Schubert-Vietz, since 1804 Karl Schubert's widow, who was at that time resident in Himmelpfortgrund 10 and who was 51 years old. The researcher Rita Steblin, who uncovered these records, assumed however that this person was Magdalena's daughter [Maria] Magdalena ('Lenchen'), also resident in Himmelpfortgrund 10 and at that time 17 years old (the same age as her cousin Franz Peter).

It seems more likely that the 'Magdalena Schubert' here is simply the widow Magdalena Schubert-Vietz. This makes further sense when we remember that Franz Theodor had taken up Magdalena and her daughter in 1805, after Karl's death.

From what we know, Magdalena had no means to pay Franz Theodor rent, but as a girls' teacher she would be able to do something to earn her keep. As we have already noted, Franz Theodor was not rolling in money at that time, Karl's estate was as good as worthless and he himself had his long overdue mortgage debt hanging over him – every little would have helped.

If Magdalena had started to earn her keep promptly then perhaps this is what is meant by the phrase 'permission to continue teaching girls' on the 1814 application for accreditation – that is, for all we know, Magdalena Schubert-Vietz may have been teaching girls since 1805, or perhaps even for husband Karl in his Leopoldstadt school.

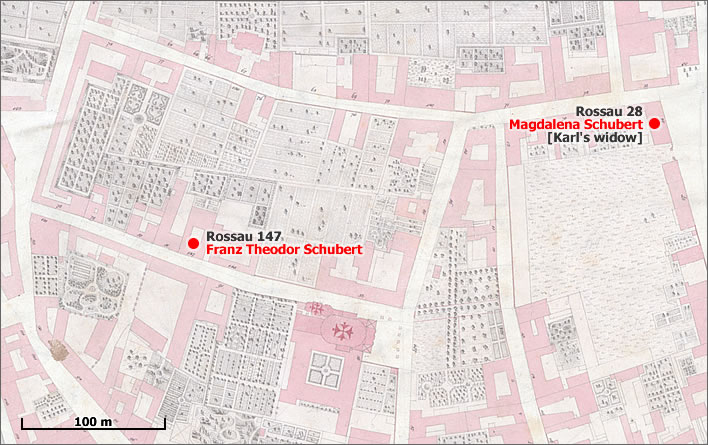

Franz Theodor opened the new school at Rossau 147, another family firm, at the beginning of 1818. We learn that there was now a separate girls' school at Rossau 28, run from her home address by none other than Magdalena Schubert-Vietz. This implies that when Franz Theodor moved his school out of Himmelpfortgrund 10 to Rossau 147, Magdalena Schubert-Vietz and her daughter Lenchen also moved out of Himmelpfortgrund 10 to her own accommodation and girls' school in Rossau 28. The accreditation she received as a teacher of girls in 1814 would still have been valid.

Franz Theodor Schubert's school in Rossau (1818-) and the girls' school run by Magdalena Schubert (Karl Schubert's widow). Image: Stadtplan, Anton Behsel (1820-1825), Rossau 1821. ©ViennaGIS/FoS.

In September 1820 another Magdalena Schubert is accredited as a girls' teacher. This really must be widow Magdalena Schubert-Vietz's daughter Magdalena ('Lenchen'), Franz Peter's cousin, who was now 23 years old. She would be joining the family firm, as it were, as a teacher in the girls' school at Rossau 28, which is where she too lived. Whether she replaced her mother or merely assisted her we do not know.

But clearly the girls' school was doing good business, since another female Schubert applied for accreditation as a girls' teacher in July 1820, this time Maria Theresia, Franz Peter's little sister, then 19 years-old, who joined the family firm alongside her cousin Magdalena. Both Magdalena and Theresia would have been in post at Rossau at the beginning of the autumn term 1820.

Thus, as we might have expected, we have a clear indication that Franz Theodor was running a girls' class within his school at Himmelpfortgrund 10 (and presumably in his earlier school at Himmelpfortgrund 72) and in his new school in Rossau. Although Franz Theodor had nominal responsibility for the separate girls' school in Rossau, the day-to-day conduct would have been conducted by his sister-in-law, his brother's widow, Magdalena Schubert-Vietz.

Theresa Grob was one year behind Franz Peter Schubert in her schooling at Himmelpfortgrund 10 (sitting on a separate bench, of course). She would have finished her school time before the move to Rossau in 1818.

The girls' school would offer companionship and convivial work in a relaxed social setting, a supervised setting in which girls of good character could happily and safely be together, whether they were technically being educated there or not.

Max Liebermann, Free Time in the Amsterdam Orphanage, 1881 (detail).

We know so little of the everyday situation in such schools. Scholarly papers are written about Franz von Schober's book-reading circle, or the production by and for the 'Linzer Circle' of the insufferably affected Beyträge zur Bildung für Jünglinge, 'Contributions for the Education of Young Men' – 'young men', nota bene. A distant country, indeed.

Of course, the ethnographer realises that in this distant country, which we lax moderns find so difficult to visualise, there was a glass wall of propriety and modesty erected between males and females.

Even in father Schubert's Trivialschule, in pre-pubertal mixed classes, girls and boys had to sit on separate benches – hence the preference, wherever possible, to teach girls in completely separate schools. Rita Steblin asserts that teachers in girls' schools could only be female relatives of the schoolteacher himself, but your author has never come across such a ruling. It is quite a plausible one, though.

We have had cause to mention on occasion on this website the coy courting rituals established for well-brought up young men and women, or that Heloise Höchner's younger sister had to provide the excuse of a having a headache in order to get them both out for a walk on the Bastei (where Heloise hoped to meet her adored Franz Grillparzer). Jane Austen fans will get the idea. A distant country.

More than half a century before, in 1752, the pious Maria Theresia had set up her Keuschheitskommission, 'Chastity Commission', which operated at the highest level of government to pursue all types of immoral or unseemly behaviour. It quickly became a laughing stock – but remained no joke: it could ruin careers and reputations on the basis of a report by some disaffected nark. Its prudery lived on long after it had faded out of formal existence.

The Rossau sewing circle

The Viennese researcher Robert Franz Müller (1864-1933) left an anecdote about his grandmother Therese Poscher's (c.1805-1869) experience of the Schubert girls' school.

Magdalena Schubert (1763-1829) […] taught young girls in female handicrafts in Rossau 28. My grandmother attended this school and became close friends with Magdalena Schubert (1797-1859), the composer's cousin, and with Therese Grob, whom she met there often. The innkeeper's daughter Anna Streim (1801-1870) also joined this group. She would become the wife of Johann Strauss senior (1804-1849). She lived with her parents in the now demolished house Thurygasse 3

Magdalena Schubert […] unterrichtete dort [im Hause Roßauerlände 21 = Rossau 28] junge Mädchen in den weiblichen Handarbeiten. Diese Nähschule besuchte auch meine Großmutter und schloß dort mit Magdalena Schubert [1797-1859], der Cousine des Tondichters und mit Therese Grob, die sie dort oft antraf, innige Freundschaft. In diesen Bund wurde auch die Wirtstochter aus der Thurygasse Anna Streim [1801-1870], die später die Gattin Johann Strauß des Vaters wurde, aufgenommen. Diese wohnte mit ihren Eltern in dem heute nicht mehr bestehenden Hause Thurygasse 3.

For a few lines we have a glimpse into the social life of the female community in the suburbs of Himmelpfortgrund, Lichtental, Thury and Rossau. It is fair to say that Franz Theodor's schools were an important component of the social dynamics of these communities.

Franz Theodor started teaching there in 1786 and in the near half-century from that moment until he died in 1830 (when Ignaz took over) generations of locals would pass through his portals, getting to know each other and the Schubert family intimately. Amongst those who passed through those portals were the Schubert children themselves, whose integration into that community was total.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!