Bye bye, democracy. Hello, general will

Posted by Richard on UTC 2015-09-28 13:24

We seem to be reading more and more these days about the limitations of democracy and the need to mobilise for the common good – generally to save the Earth, the world, often even the planet. Such arguments are made with a po-faced air of conviction in the obviousness of their case. The worst are indeed 'full of passionate intensity' as Yeats wrote. All this can only mean one thing: the zombie has awakened and is walking abroad once more. In every age this particularly dangerous zombie emerges from his box to cause mayhem and despair among the living. His name? Jean-Jacques Rousseau (human: 1712–1778; zombie: 1778–present).

Rousseau was a novelist, essayist and musician. Some call him a philosopher. His personal life was reprehensible. His treatment of the many people who helped and supported him was disgraceful. We find no morals in his conduct, which seems to have been entirely based on immediate self-interest.

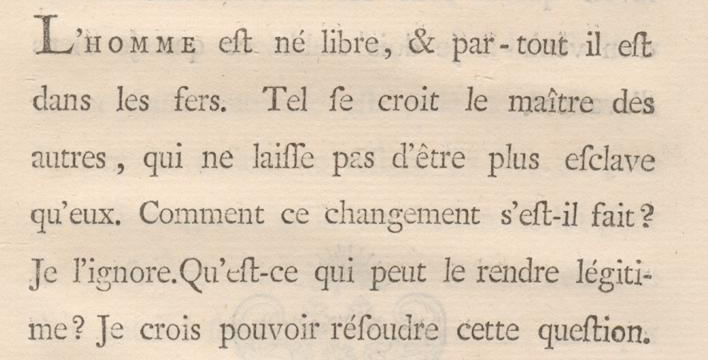

Take any 'philosophical' statement of Rousseau's and shine the light of reason and analysis on it and it will crumble to dust like some zombie artefact dragged from the crypt into the sunlight. Take his most famous quote, the first lines of his work The Social Contract: 'Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. Those who think themselves the masters of others are indeed greater slaves than they.'[1] Ponder that. What does any of that mean? These sentences have been quoted again and again, but I challenge anyone to give a rational explication of them.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du contract social, ou, Principes du droit politique, Amsterdam, 1762, p3. Source: Bibliothèque de Genève.

A human baby is not 'free' in any sense of the word: it is totally helpless. Compared to other organisms, the offspring of humans have an extremely long biological dependence on their parents, an even longer social dependence and in modern societies a legal dependence usually until about 18, in some places 21. In fact, we are never free, we need each other too much. You say to me: but this sentence is not to be taken literally, it is a metaphor. Well, if you insist. But a metaphor for what?

Rousseau's second sentence defeats all understanding. It reminds me of the nonsense Thoreau wrote in Walden, as he watched those idiots who, unlike him, didn't live in a hut on an exclusive diet of beans but got up in the morning, raised children, kept animals, worked the fields and grew food for others: they had enslaved themselves, he thought. Whilst others were labouring, he could go and contemplate the pond or hoe up and down his bean rows. Despite his contempt for the self-enslavement of the people of Concord to their possessions, he was happy to barter his beans for all the useful things he needed and which their enslavement produced – nails, planks and tools. Other idiots made his clothes, his shoes, his paper and his ink. Without all these idiots his life in his shed would have been nasty, brutish and short indeed. As it is he managed two years or so of hut life. At least Thoreau's prose is comprehensible, if wrongheaded. Rousseau's is just nonsense.

Yes, I know. You don't have to tell me: Rousseau sparkles and I plod. That is the danger, I reply. These statements are just demagoguery, 18th century sound-bites. After reading The Social Contract a learned contemporary called him the 'new Diogenes', alluding quite accurately to the legendary lunacies of that crazed Greek, who, as we all remember, was another free-thinker who rejected polite society, who lived in a barrel, behaved like a dog and went looking for wise people with a lamp.

It is true: Rousseau's writings are compelling, but to what purpose is another matter. His readers slither across the glittering surface of his prose like flies on a pond. He has the demagogue's magical powers: for nearly two and a half centuries people have read into his words whatever they wanted to read. Freedom, nature, childhood innocence, chains – yeah, I'll have some of that. All the dogwhistle words are there, just not connected in any way that makes sense. Despite their confusion and general incomprehensibility his books were best sellers, even when banned.

Paradox upon paradox. The man who abandoned his own children and put them into an orphanage – at that time effectively a medical death sentence – and also maintained that only a few people should be educated anyway and the rest left stupid is, even today, lauded as a great educationalist. The man who held that the private ownership of property was theft and who took the Greek city state of Sparta with its unyielding, totalitarian militarism as his model is held to be a great champion of freedom. The man who held intellectual and technological progress to be bad for us, who thought we should return to some previous, unspecified time in the past and throw out all scientific, technological and medical progress is considered a great progressive thinker. We should listen carefully to Voltaire: he detested Rousseau.

Paris

Rousseau the Undead first crawled out of the sodden soil of his lake-island grave a little over ten years after his burial. He staggered around among the unhinged sansculottes of the French Revolution as they howled with mindless rage. Voltaire may have despised him, but the monster Robespierre loved him – that fact alone should tell us all we need to know about Rousseau. His work delivered a glib, pseudo-philosophical justification for the massacre of more than 40,000 people in the space of about four years: the concept of la volonté générale, the 'general will'. This astonishing force, which no-one has ever managed to explain, does not arise from a democratic majority. No one votes in Rousseau's world and so no one now should call him a democrat. The general will just mysteriously crystallises out in the heads of leaders as 'the right thing to do'.

It was the justification used for almost every death during that awful time. In September 1792, the demagogue monster Danton suggested that the 'traitors' in the prisons of Paris were a threat to the new republic. The general will moved in its mysterious way and over the course of three days about 1,400 prisoners – priests, aristocrats, tradesmen, servants – were dragged out of their cells and slaughtered (the word is completely appropriate). At the start of the following year, 1793, the general will gave Louis XVI a show trial and lopped his head off; the head of his queen would roll after another show trial a few months later. In the bloodbath of what became known as the 'Terror' it was the general will that selected the victims. Those who had been born free were now in real chains and awaiting their appointment with 'the barber'. Quelle drôlerie! Next please!

Charles-Louis Muller, Roll Call of the Last Victims of Terror, c. 1850. The general will has spoken. Your tumbril awaits, Madame!

Here is a great irony: even Thomas Paine, the author of the Rights of Man and one of the fathers of the American revolution, ended up in a Parisian dungeon and only escaped the sharp blade of the general will by an astonishing fluke. A further great irony: on 11th October 1794, a few days before Paine escaped the guillotine, the mouldering body of Rousseau the Undead was fished out of its soggy grave where it was having a brief nap and placed in the Panthéon in Paris, a completely fitting bookend for the Terror. Ironies come in threes it appears: his tomb is now located directly opposite that of his enemy Voltaire, both garlanded equally these days with bemused foreign tourists. Unfortunately, Voltaire is dead, but Rousseau is still very much undead.

Not only Voltaire but also Bertrand Russell, writing in 1946 shortly after the forcible removal of a few Grendels from the world stage, found Rousseau's works philosophically incomprehensible. Russell saw in them the spirit that had been used by all the worst totalitarian despots since the zombie first crawled out.

The Social Contract became the Bible of most of the leaders in the French Revolution, but no doubt, as is the fate of Bibles, it was not carefully read and was still less understood by many of its disciples. ... [B]y its doctrine of the general will it made possible the mystic identification of a leader with his people, which has no need of confirmation by so mundane an apparatus as the ballot-box. [2]

Berlin and Moscow

Since 1794 the zombie has slid back the lid on his tomb in the Panthéon and staggered out whenever he has been called. He has not been idle: Communism, Bolshevism, Trotskyism, Stalinism, Maoism, National Socialism, all in their own way make an appeal to Rousseau's mood music. All these monsters claimed to be the agents of the general will, just as the French monsters did two and a half centuries ago – it was all in the best interest of their people. Anyone who can't be bothered with the messiness of democratic process invokes the general will – it is always the 'good thing', the 'right thing' to do. Russell again:

Its first-fruits in practice were the reign of Robespierre; the dictatorships of Russia and Germany (especially the latter) are in part an outcome of Rousseau’s teaching.[3]

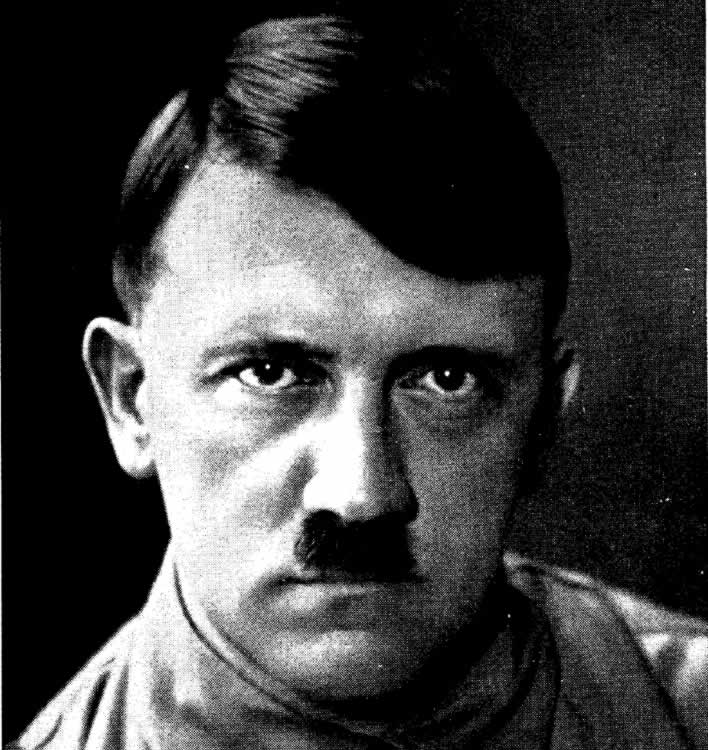

The Nazis? you say. How can pauvre Jean-Jacques, as he liked to style himself, be considered to be a Nazi thinker? Victor Klemperer, a Jewish (Protestant!) Professor for Romanic Philology at the Technical University of Dresden saw this clearly. Klemperer kept acribic notebooks recording the 'small history' in Germany from the moment the Nazis seized power in 1933 until their obliteration in 1945 – a daily record of ever increasing tyranny and spiteful, shameless oppression. His own survival through the daily depredations of a life lived under the jackboot is a great miracle. Despite all the chaos and humiliations around him, he kept on writing in secret both his diary and his two volume work on 18th century French Literature. Volume 1 was mainly Voltaire, Volume 2 was mainly Rousseau. Klemperer was a thinking man who was exposed simultaneously to Stalin's Bolshevism, Hitler's National Socialism and Rousseau's confused sparkles. He realised how astonishingly alike all three were. Immersed in Rousseau's work and simultaneously immersed in Nazi propaganda he saw many parallels in language and reasoning.

Property was theft? – the Nazis turned forced confiscation of private into an art form. Sparta was the ideal? – how much of Germany's golden youth was tossed away in glorious but hopeless combat, never to surrender? Rousseau and Goebbels were capable of contradicting themselves within two sentences without damaging the mesmerising flow of their rhetoric. It didn't matter. The only thing that mattered was the radiance of the rhetorical present. Klemperer's diary[4] through those dreadful times is studded with instances of the equivalences between the minds and language of Stalin, Hitler and Rousseau. All three shared the same thought processes and the same erratic egotism. Because they thought it, it must be right. In their last years all three were lunatics with extreme persecution complexes. Rousseau himself never became a demagogue: his mind was too erratic and unfocused for that. He just left behind all the ideas and specious justifications that others needed for that task.

Adolf Hitler on the frontispiece of the 1936 edition of Mein Kampf. Key expressions in the Nazi vocabulary: 'will', 'fanaticism' and the 'leadership principle'.

Klemperer's view is extended by someone from the other side of the divide: Günther Franz was a professor of agrarian history, who had been a Rottenführer (group leader) in the SS, so, in terms of Nazis, he knew whereof he spoke. After the war his rehabilitation finally came after a long wait. He noted Rousseau's glorification of the peasant as leading a life close to Nature and his simultaneous demand that peasants should not be educated, so as not to spoil them. They were to be kept stupid. Their state was sufficient as it was, agricultural progress was unnecessary. The tractor, the milking machine would be inventions that led to degeneracy.

The farmer was held to be an exemplary person, to be the core of the people. We can thus follow the threads from Rousseau and Hirzel through Riehl and Gotthelf to the Blut-und-Boden ideology of the 20th century.[5]

We do not need to spend much time looking at Bolshevism – as the Nazis liked to call it – that mirror image of National Socialism, with its equally institutionalised contempt for the masses. The masses were always just a stupid mob: the worthless Lumpenproletariat, who had no idea of their position in society and history but who could, with caution, be useful to the revolution; the proletariat, who were just confused and mistaken about their position and needed to have their heads straightened out by their revolutionary betters before anything useful could be done with them. Finally they all just become the same malleable, worthless clay – the tovarisch, the (Volks-)Genosse – the dumb-ox peasants who can be extinguished in their millions, on their farms, on roads heading east and west, in camps, at the gates of Stalingrad or under the rubble of German cities, or driven from their homes with no more than the clothes they are wearing and a small suitcase. And all these crazed -isms have their foundation in a rejection of constitutional order at the expense of the belief in the rightness of a leader's ideas: the general will.

Switzerland

But, astonishingly, Rousseau is still applauded by intellectuals around the world. Many French call him a hero and claim him for their own, when, in fact, any right-thinking French person would have shuffled their feet a bit and tried to pretend the Genevan was really Swiss and therefore nothing to do with them. Even more astonishingly, the otherwise ever-so democratic Swiss seem to love him too. His muddled ideology has sunk deep into their muddled modern heads.

In 2012, the 300th anniversary of his birth, the Swiss state broadcaster reserved a whole week for discussions of Rousseau's bizarre Luddite ideas. Irony upon irony: the organizers set up a flashy website[6] for the old technophobe and even won a prize for it.

In the discussions during that week academics mused about the general will as a means of putting an ethical patina on action against social heretics – especially climate heretics, who clearly only think of their own self-interest in wanting low fuel prices for their gas-guzzlers. However, such selfish knuckle-draggers can account for a large number of votes: every Swiss referendum decision on saving the planet has gone the Neanderthals' way so far.

Surprisingly, the resistance at the ballot box has had no effect. Public feeling is powerless in the face of the general will as it is conceived by the political and media classes. As governments become administrations rather than political entities, the general will and its legal counterpart, the 'common good', are invoked in numerous fields, but 'climate change' policy is the most egregious at the moment. There is a 'cause', an overriding cause, and that is always dangerous. How can we save the planet with so many SUV-driving knuckle-draggers around? Easy. The Swiss government works around the voting results: the rejected measures are renamed and the administration trundles forward with its plans anyway because, in Rousseau's world, votes don't count. Problem solved: the general will wins. The high priests of the global warming cult envisage supranational bodies that will take decisions for our own good, decisions that are made by the general will. Under this scheme individual nations will have no real say in these decisions and will simply be their executors. Their politicians can shrug their shoulders and say: nothing to do with us. Their own citoyens in turn will just have to do what is best for them. Democracy – Churchill's least worst system – is becoming to look less worse every day.

Noble lies

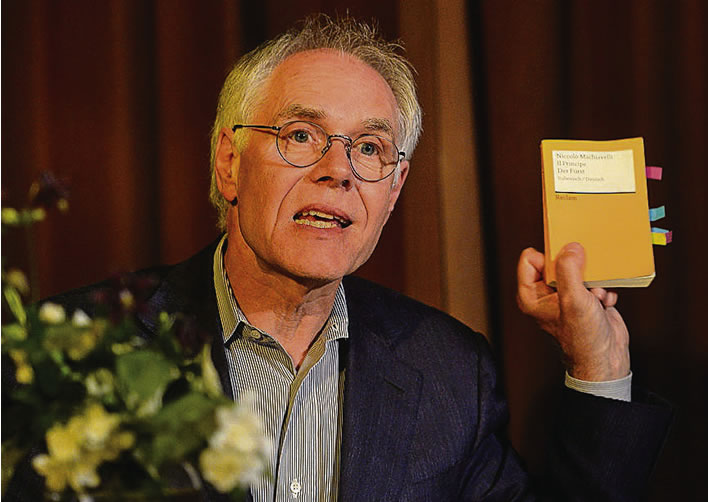

I exaggerate? Let us stay in the home of democracy and quarterly voting for a while. When the much hyped Climate Conference in Copenhagen in December 2009 ended in a snowy, impotent fiasco – remember it? the private jets, the limos, the discount hookers and best of all, the mass of snow that fell on them? Yes, that climate conference that contributed so much to the gaiety of a cold winter. Remember, too, that 'Climategate' had hit the news just a month before: the 1,000 or so leaked emails that showed climate researchers in an interesting light. Well, after all that, the long-serving, socialist Swiss Energy Minister Moritz Leuenberger went back home and officially announced to his parliament and people that Copenhagen 2009 had been a great success. Leuenberger, who had also even served two terms as President, simply lied. There is no euphemism we can use – he lied. The reason: a referendum on measures to curb carbon dioxide emissions was going to be held shortly thereafter and the failure of the conference 'would have been disastrous'.

You are shocked that I call him a liar? It is a badge he wears with pride. In June of this year, five years later and now safely out of government, he gave a speech[7] in which he said that lying about Copenhagen had been necessary to achieve his ends. He expressed no regret over this, on the contrary. For it was a lie in a 'good cause', a 'noble lie', a justified lie. It was what politicians had to do, even in what is arguably the most democratic country in the world. The Lumpenproletariat may nowadays have a vote but they just don't understand what to do with it unless you lie to them. Nota bene: he is a trained lawyer.

Former Swiss Energy Minister Moritz Leuenberger holding up Machiavelli's The Prince in Ermatingen, Switzerland in 2015. Photo: Tagblatt Online/Nana Do Carmo.

Despite his proactive fibbing, that referendum was indeed a disaster for Leuenberger. Never mind. Our zombie, Rousseau, pats the minister's shoulder with a rotting hand – 'his finger-bones / Stick through his finger-ends' – and whispers 'La volonté générale, mon fils'. That's why it all came right for them in the end. Targets were set, emissions were regulated, taxes and Lenkungsabgaben (so-called 'steering taxes' to change behaviour) were raised and penalties imposed; directives were issued, building technology was regulated, acceptable limits were defined; schools were alerted, curricula changed and teachers and pupils encouraged to pull together for the sake of the planet; schemes were proposed, plans designed, 'energy towns' designated and Stakhanovite awards offered. It all sounds dreadfully familiar to me.

Am I calling today's eco-warriors Nazis? Of course not. Nowhere near: the horrors of the 20th century -isms must not be trivialised in a such a way. But it is important for those eco-warriors to realise that when they talk of the general will and the common good and ponder ways to bypass democracy they should also realise what zombies they are calling up as legitimisation of their deeds. Be careful what you wish for, indeed.

Even as long ago as 1946 Bertrand Russell saw the danger: 'What further triumphs the future has to offer to [Rousseau's] ghost I do not venture to predict'.[8] The lid has slid open and the sarcophagus in the Panthéon is empty once again, the foreign tourists look puzzled. Rousseau strides the Earth but Voltaire's dust lies undisturbed. We have had Sansculottes and Nazis and Bolsheviks. Whatever next? How do you kill a zombie? I wish I knew.

References

-

^

L’homme est né libre, & partout il est dans les fers. Tel se croit le maître des autres, qui ne laisse pas d’être plus esclave qu’eux.

in Jean Jacques Rousseau, Du Contrat Social - ^ Bertrand Russell, History Of Western Philosophy, Unwin, London 1946/1961, p 674.

- ^ Bertrand Russell, ibid.

- ^ Victor Klemperer, Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten, Tagebücher 2 Bde: 1933-1941/1942-1945, Aufbau Verlag, Berlin, 2015.

- ^ Günther Franz, Geschichte des deutschen Bauernstandes vom frühen Mittelalter bis zum 19. Jahrhundert, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart, 1970.

- ^ JJR2012: Jean Jacques Rousseau heute

-

^

Er selbst habe im nachhinein bemerkt, dass er ab und zu, gerade was Volksabstimmungen anging, wissentlich Informationen nicht weitergegeben oder abgeändert habe. «Der Klimagipfel in Kopenhagen kurz vor der Abstimmung zur Reduktion des CO2-Ausstosses war desaströs», gibt Leuenberger jetzt zu. Doch damals habe er dies absichtlich nicht den Medien gesagt und somit gelogen, damit die Schweizer dafür stimmen würden. Leuenberger: «Jetzt glaube ich, die Lüge ist legitim, wenn sie etwas Gutes bewirkt.»

in Tagblatt Online: 1. Juni 2015, 06:52 Uhr - ^ Bertrand Russell, ibid.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!