All Saints' Day, 1 November

Posted by Richard on UTC 2015-11-01 10:12 Updated on UTC 2018-10-03

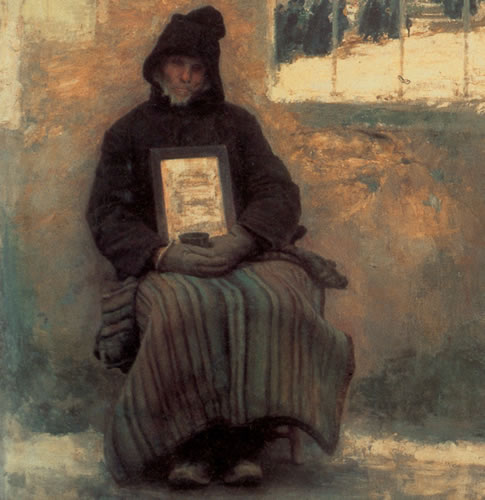

Here is a painting entitled La Toussaint ('All Saints' Day') by the French artist Émile Friant (1863–1932). He painted it in 1888. Trying to describe a painting in words is nearly as pointless as trying to describe a piece of music. Nevertheless let's try, because there are depths in this painting that are easily overlooked.

Émile Friant: La Toussaint, tableau représentant une scène de Toussaint au Cimetière de Préville, à Nancy. Peinture à l'huile sur toile, 254 × 334 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nancy, 1888.

The location is the Préville cemetery in Nancy, in north eastern France, part of the region in which Friant grew up. Knowing the exact location is actually unnecessary, but interesting nevertheless. Even without the title it would be absolutely clear that this was a painting of a scene on All Saints' Day or All Souls' Day: the season, the location and the clothes allow no other conclusion. There are three major components in the painting: the family, the blind beggar and the cemetery. Let's take them one by one.

The family is dressed in black mourning clothes, which we would expect on such a solemn occasion. They are well dressed, too, meaning that they belong to the well-to-do bourgoisie. Two of the women are carrying flowers, one as bouquet, the other as plant in a pot. The flowers are chrysanthemums, which, being late-flowering and hardy, are a traditional flower for grave decoration at this time of year.

It is striking how quickly the family is walking for such a solemn event. The object of their visit is not going anywhere, so a few minutes here or there wouldn't really matter. Their pace is perhaps because of the cold, or perhaps they just want to get past the beggar as quickly as possible. This latter option must be the case: just note their gaze. The adults are looking studiously forward or away from the beggar. The young woman with the pot of chrysanthemums is looking away, shielded by the flowers from this unattractive figure. One of the the older women is looking at the young girl, who has been delegated to put some money into the beggar's cup.

The fact that the adults have given the child money to give to the beggar instead of giving it themselves is in itself quite telling. Only the girl is looking at him, perhaps with an innocence that has not yet been tainted by the social discomfort of the adults. But we note that her hand with the money is also held out long before it needs to be. The action is that of a child giving a treat to a potentially dangerous animal kept at arm's length. All pointless as far as the blind beggar is concerned: he cannot see anything of this posturing.

The beggar is blind and is sitting completely passively on a stool with his back to a pillar of the cemetery wall. His back is, quite literally, against the wall, his passivity a metaphor for his situation in life: he has no options left, there is nothing he can do that will improve his position. His blindness makes a mockery of the attempt by the rich family to avoid eye-contact with a sightless man. Money will be given, an act of charity will be performed, but the blind beggar, scratching to retain a hold on life but waiting by the gates of the cemetery for what will soon come, has for them less meaning than the decomposing corpses already inside. The coins will be dropped into his cup by unknown people who then hurry past. The isolation of his figure in the painting reflects his social isolation, above all the social distance between him and the rich family. Let us not quibble over the appelation 'rich': whether the family is rich or well-off or bourgeois, they have a standard of life that is utterly apart from his squalid misery.

The rendering of the cemetery through the railings in the background is masterpiece of understated suggestion. The foreground of the picture, the flowers, the faces of the family and even the veils the women are wearing are painted with precision. The next layer is the beggar, rendered slightly more coarsely: his passivity and social non-existence not requiring great detail. He is what he is: it doesn't matter who he is. The cemetery itself and the throng of black-clad figures against the snowy ground within it needs no further detail than that which Friant gives it. We see the cemetery through the railings of the wall. There are no railings in the cemetery wall today, about a century and a quarter later, which might mean no more than that Friant had to open up the wall with some minimalist railings in order to include the view of the cemetery. Artists are allowed to do things like that.

In addition to these three visual components there is, however, a fourth element: the picture itself. The painting is much more than a snapshot of a scene from everyday life: a 'genre' painting. Friant was a classically trained artist and as such stood in a long tradition of metaphorical art. Friant was not a photographer with a brush instead of a camera. Each of the elements is deliberately placed in this composition and the relationship of the parts leads us into a deeper understanding of the situation.

Firstly, the title of the work is 'La Toussaint'. It is not 'family visiting dead relatives' or 'cemetery scene' or 'visiting the grave'. The painting is about All Saint's Day itself, not the participants. I'll leave you to delve deeper into such things, but for me, personally, I am forced into deep thoughts about an institutional occasion that leads to expensive gestures for mouldering graves and trivial displays of virtue for cases of desperate human hardship among the living.

Secondly, the layers of the painting pass us inexorably from life into death. The cemetery wall is a frequent metaphor for the boundary between life and death and the act of passing beyond it. Do you think that my fervid brain is imagining things, reading too much into this scene? Well, maybe. It still puzzles me that, if this metaphor of the wall as the boundary between life and death is not there, why does a wall take up two thirds of the painting?

Here endeth the meditation for All Saints' Day. It gets worse tomorrow.

Update 03.10.2018

A photograph of a woman buying flowers on All Saints' Day in Paris in 1911. The flowers are, of course, chrysanthemums.

Image: photographer unknown, source Vintage Everyday.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!