The grass on the weirs

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-02-01 13:24

In these times of uncertainty and fear let us begin February with an affirmation of serenity.

In 1916 the Irish poet W.B. Yeats (1865-1939) wrote in his autobiography Reveries over Childhood and Youth of his memories of growing up in Sligo on the west coast of Ireland and living with his grandparents, the Pollexfens.

Once every few months I used to go to Rosses Point or Ballisodare to see another little boy, who had a piebald pony that had once been in a circus and sometimes forgot where it was and went round and round. He was George Middleton, son of my great-uncle William Middleton. Old Middleton had bought land, then believed a safe investment, at Ballisodare and at Rosses, and spent the winter at Ballisodare and the summer at Rosses. The Middleton and Pollexfen flour mills were at Ballisodare, and a great salmon weir, rapids and a waterfall, but it was more often at Rosses that I saw my cousin. [1]

Twenty or so years later the delicate boy is now a 24 year-old late-Victorian poet sporting floppy neckwear. He wrote a poem 'An Old Song Re-sung' and published it in his first book of poems, The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems (1889). In a footnote to the poem he placed the location and inspiration of the poem in Ballisodare:

This is an attempt to reconstruct an old song from three lines imperfectly remembered by an old peasant woman in the village of Ballysodare, Sligo, who often sings them to herself. [2]

Yeats was never happy with his first volume and edited and sliced the collection and its poems almost as soon as it appeared. The poem we know now is called 'Down by the Salley Gardens' and appears in his book Crossways in 1889.[3]

Here is the first verse:

Down by the salley gardens my love and I did meet;

She passed the salley gardens with little snow-white feet.

She bid me take love easy, as the leaves grow on the tree;

But I, being young and foolish, with her would not agree.

Yeats was still in the soft-focus world of the poets of the 1890s, dreaming his soft-focus Irish dreams. A modern reader will probably find this verse twee, perhaps even syrupy. He ditched most of the poems in The Wanderings of Oisin except for four, one of which was 'Down by the Salley Gardens'.

Willow coppices

That said, the expression 'salley gardens' in among this fustian excites our curiosity but was left unexplained by Yeats. Perhaps at the end of the nineteenth century it was a common expression in rural Ireland. The phrase certainly lifts the poem slightly out of its banality, but now requires some exigesis for modern readers.

The word salley is the terminal anglicism of a great word that has descended down the Indo-European language tree, mutating as it passed down. It refers to a tree that the modern English call the willow. There may even still be some rural geriatrics who might call the tree sallow. The etymology of the English willow is not completely clear, but sallow is aligned with the many descendants to be found throughout all the European languages. We should not be surprised that such a useful tree has carried its name down the ages and into so many human tongues. salix in Latin, salce in Italian, sauce in Spanish, salisch in Romanisch, finally to lose its final consonant in French saule and the anglo-Irish salley. By the way, the French call the name of an orderly plantation of willows a saulée, intriguingly close to the willow coppice we hear in salley garden.

This useful tree, friend to man throughout history, supplies flexible thin branches that can be used to manufacture everything from household baskets, fish and eel-traps to lobster baskets. It had the utility of modern plastic before plastic was invented. Its German name, standing aside from the sal- etymology, is Weide (sometimes Salweide), derived from Middle and Old High German wide/a meaning 'flexible', 'bendable'. Even its extremely bitter bark had medicinal properties which we now recognize in the chemical name for that miracle drug, aspirin, acetylsalicylic acid.

Another property of the willow that made it even more useful is its ability to be 'coppiced'. If the stem of the tree is cut down, many young shoots, perfect for weaving, will rapidly grow in a crown from the stump and can be 'harvested' only a few seasons later. Such a willow coppice deserves in every respect to be called a 'garden'. It is an important resource for the village. Hazel is another similarly useful tree that can be coppiced. The willow thrives in the wet, and we are not surprised to find the dwellers on the Ballisodare river have created a 'salley garden', such as we would find in many traditional villages near water. It would certainly be a discreet place for lovers to meet.

Thundering weirs

Well, that's cleared up the first verse, for modern taste a rather maudlin four lines, let's face it. Now, in the second verse, Yeats the still-to-become great poet engages poetic gear.

In a field by the river my love and I did stand,

And on my leaning shoulder she laid her snow-white hand.

She bid me take life easy, as the grass grows on the weirs;

But I was young and foolish, and now am full of tears.

Much better. We have a clearer sense of place than that implied by 'salley gardens' in the first verse. We are in a 'field by the river'; two lines later we hear of 'the weirs'. We may still be a little queasy at 'on my leaning shoulder she laid her snow-white hand', but at least it has more action than anything in the first verse.

We now find that the poem has come together from the tweeness of the first verse. We see the hard structure behind the soft surface and the artifice, the poetic intelligence that created it.

| Verse 1: the coppice | Verse 2: the river |

| willow coppice | field by river |

| meet | stand |

| snow-white feet | snow-white hand |

| take love easy [lovers' dispute] | take life easy [i.e. farewell advice] |

| leaves on tree [in coppice] | grass on weirs [in river] |

| would not agree [lovers' dispute] | full of tears [end of the relationship] |

| Situation: The lovers are meeting. | Situation: The lovers are parting. |

If there is one sure way to kill the glamour of a poem it is deconstructing it, just as we have done here. However, at least we have shown that on careful reading the poem is not just about two soppy lovers feeling sad. It is a relationship where the man, full of passion, wants more and the girl, full of wisdom, wants time. The differences between them in the first verse cannot be reconciled and the parting takes place in the second: 'She bid me take life easy' – that's a farewell.

But above all we are struck by the phrase 'as the grass grows on the weirs'. We remember from Yeats' biographical account the 'great salmon weir, rapids, and a waterfall' at Ballisodare, and truly they are there and the grass still clings serenely onto them, untouched by the thundering torrent all around.

Views of the weirs, rapids and falls at Ballisodare, County Sligo, Ireland. The stillness of small clumps of green growing on the thundering weirs.

This surely is the crux of the poem, the need to retain calm, a sage-like serenity among the roaring tumult of life and love. And, of course, the fact that you didn't do it and are now filled with regret at that realisation.

The ghost of Uncle William

In 1945, just over a fifty years after 'Down by the Salley Gardens' was first published, the American poet Ezra Pound was being held a prisoner in the United States Army Disciplinary Training Center outside Pisa, accused of treason. Starting during his six-month imprisonment there he wrote the section of his magnum opus, The Cantos[4], entitled The Pisan Cantos. (You can always tell a true writer: however bad the circumstances that they are in at any moment, they will be there scribbling away. In situations in which most of us would sit in a dark corner and burst into tears, writers pick up a pen and start scribbling. In a dungeon they will find a piece of burnt bone in their food and start scribbling Pindaric odes on the rock walls with it.)

Pound had started The Cantos in 1917 with an adaptation of Odysseus' journey to Hades, to seek advice from the shade of Tiresias, the Theban soothsayer. In Pisa there were many ghosts: the great figures of his years in London and Paris were now almost all gone – Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (†1915), Henry James (†1916), Ford Madox Ford (†1939), James Joyce (†1941), W.B. Yeats (†1939) and others too numerous to mention here.

In the prison camp at Pisa, initially sleeping on concrete in a reinforced cage, later in a tent, expecting his own execution to be among those that took place there, these ghosts of his past appeared to him, much as the shades had appeared to Odysseus in Canto I, all those years ago in London in 1917.

The famous lunch held to honour Wilfrid Scawen Blunt at his Sussex manor house in Sussex on 18 January 1914. L-R: Victor Plarr, Thomas Sturge Moore, William Butler Yeats, Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington, and F. S. Flint. Photograph: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

This remarkable occasion is dealt with in detail by Lucy McDiarmid in Poets and the Peacock Dinner, Oxford University Press, 2014.

The 82 year-old Pound visits the grave of James Joyce – 'Jim the comedian' – in Zurich's Fluntern cemetery in 1967. Photograph: Horst Tappe.

Pound's ghosts did not linger, nor were they intact. Like all the breakthroughs into the other world that came to him in Pisa they existed 'only in fragments unexpected excellent sausage, the smell of mint'. His visions came not in person, but in fleeting phantasmagoria, fractured memories. The Muses, as he correctly tells us, being the 'daughters of memory' [74:445] (Mnemosyne). At one point, out of the fog of his years in England, (1908-1920), Yeats, 'Uncle William', rose into his mind and a nexus of meaning clustered around that memory:

the sage

delighteth in water

the humane man has amity with the hills

as the grass grows by the weirs

thought Uncle William consiros

as the grass on the roof of St What's his name

near 'Cane e Gatto'

soll deine Liebe sein

[83:529]

The phrase 'as the grass grows on the weirs' makes us sit up and pay attention now. But as usual with Pound we have some legwork to do before we can begin to untangle his fragments. Let's take it step-by-step.[5]

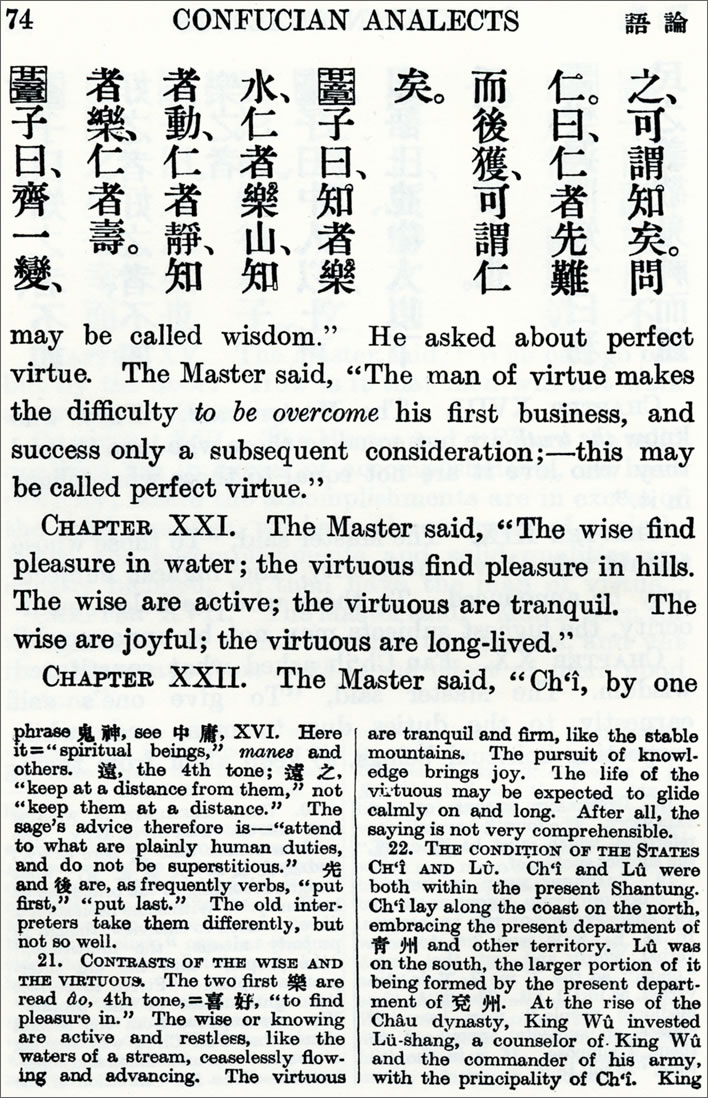

The sage… is paraphrased from Confucius, The Analects, Book 6, xxi.

In Pound's translation: He said: the wise delight in water, the humane delight in hills. The knowing are active; the humane tranquil; the knowing get the pleasure, and the humane get long life.[6]

Confucius, Analects, Book 6, xxi, as rendered by James Legge in The Four Books, Shanghai 1923/New York 1966. It pleases me that the great sinologist Legge finds the meaning of the passage as baffling as I do (see his note).

The grass on the weirs: Stillness amidst turmoil in 'Down by the Salley Gardens'. Also the admission of foolishness (see the following, consiros, which is placed on the same line).

Consiros: In the Divine Comedy, Purgatory, 26:143, Dante meets the soul of Arnaut Daniel (fl. 1180-1200), a Provençal troubadour. Pound, recognising a fellow obscurant, was a particular fan of Arnaut's difficult trobar clus, his 'hermetic songs'. Dante's respect for Arnaut is so great that the troubadour's words are given in his own tongue, Provençal. Arnaut, who is being purged in the fires of Purgatory, looks back and sees his own folly: consiros vei la passada folor, / e vei jausen lo joi qu'esper, denan. 'Reflecting, I see the folly of my past and look forward to the hoped for joy'. [consiros: literally 'thoughtful,' cognate with Latin considerare.]

Ezra (in prison), Arnaut (in flames) and the narrator of 'Down by the Salley Gardens' (dumped by the girl) all now realize the error of their ways in their hasty actions.

The grass on the roof: The church with the grassy roof in Pound's time, 'St What's his name', is San Giorgio in the Via di Pantaneto, Siena, Italy. There is a narrow street off the Via di Pantaneto nearby called Cane e Gatto, 'Dog and Cat'.

soll deine Liebe sein: is a line from a German song 'Still wie die Nacht'. The song is doggerel, which has not prevented it getting into the canon of German Volksmusik. For obvious reasons the author of the lyric preferred to remain anonymous. I give the German here for the record.

Still wie die Nacht / und tief wie das Meer, / soll deine Liebe sein!

Wenn du mich liebst, / so wie ich dich, / will ich dein eigen sein.

Heiß wie der Stahl / und fest wie der Stein / soll deine Liebe sein!

This rubbish was given an appropriately execrable musical setting by Carl Bohm (1844-1920) and was first published in 1889 in Berlin. In his early years in London Pound earned a few shillings by writing concert reviews. If he did hear it publicly performed in London it was probably in the English translation by Nathan Haskell Dole (1852-1935). Dole was an all-purpose jobbing translator and scribbler of the time and provided a terrible translation to match the terrible original text and the terrible music:

Calm as the night, / Deep as the sea, / should be thy love for me!

If love like mine / glow in thy heart, / I am for ever thine.

Fervent as steel, / And firm as the hills, / Should be thy love for me!

It would be a mistake to assume that Pound, that great critic of the squishy doggerel of that time, by calling up soll deine Liebe sein implies any approval of the poem as a whole. He is a fine magpie, capable of picking here and there. But the idea of love being 'calm as the night, deep as the sea' is directly cognate with Yeats' 'as the grass grows on the weirs', the centre of Pound's current meditation.

Grass nowhere out of place

As so often with these crazy poets, we have to dig even deeper: in this case there's a lot more to grass and roaring water than meets the eye.

Grass was a favourite object of Pound's. He used one memorable phrase, 'grass nowhere out of place' directly on three occasions in The Cantos:

- in [43:219] during a note on a 'wheat scheme' in Siena (readers who are still awake will remember that as the location of the church of San Giorgio and its grassy roof);

- in [51:251] adjoined to a remark of the scholastic philosopher Albert the Great on the 'godlike intellect' that has 'grasped' – in a Canto that begins with the Neoplatonic statement: 'Shines in the mind of heaven God who made it more than the sun in our eye';

- in [74:435] in the context of many divine manifestations in the Pisan prison camp.

Grass is a frequent indirect presence in the Cantos, too frequent to go into here. It often signals the presence of the unseen, as in [74:444], when it turns in the wind, revealing the invisible.

Water, too – whether still, smoothly flowing or tempestuous – also appears too frequently to discuss here, if anything more often than grass.

Yeats and Pound were both strongly influenced by Neoplatonism.[7] They both used the metaphor of water as an image of the nous, that Platonic fluid representing our everyday world.

There is plenty of evidence for this in Yeats' writings – his late poems, 'The Delphic Oracle upon Plotinus' (1931) and 'News for the Delphic Oracle' (c. 1938) are fun examples.

Pursuing the imagery of water in Pound's work would lead us down many rabbit holes, through many tunnels, possibly never to emerge into the light again. After many hours we would look up from our mound of books, hundreds of scribbled notes, cross-references and cups of cold, unfinished coffee and we would realise that we still cannot see fully into his head, but what we can comprehend is fascinating, beautifully expressed and, possibly, completely misunderstood. Someone, somewhere will come up with an allusion that we have missed and the chase will be on again.

What, therefore, can we say with certainty? Only that finally, in 1945, in the dust and heat of the Pisan summer, two writers are united by the symbolic vision of grass that is 'nowhere out of place', that can grow calmly in the most unexpected places – a church roof in Siena, the weirs in Ballisodare – grass that represents a quiet, serene existence above the turbulent waters of the everyday, the Platonic nous; the survivor full of self-knowledge and regret.

She bid me take life easy, as the grass grows on the weirs;

But I was young and foolish, and now am full of tears.

What must the restless survivor in the Pisan prison camp have thought of that? The thought stayed with him. Towards the end of his life, among the last lines he ever published, he wrote: 'That I lost my center / fighting the world' [117:802]. Consiros.

References

- ^ William Butler Yeats (1865-1939), Reveries Over Childhood and Youth, London, 1916, p13f.

-

^

Alexander Norman Jeffares, A Commentary on the Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats, Stanford University Press, 1968, p. 14f.

Jeffares researches the folk-song predecessors for the first verse of Yeats' poem thoroughly. These predecessors are mildly interesting because they show what Yeats might have taken over. But if we believe Yeats' statement that he started with an oral basis, 'three lines imperfectly remembered by an old peasant woman' – and we have no reason not to – the exact texts of the predecessors are really only of academic interest. Yeats' poem is what it is. - ^ 'Down by the Salley Gardens' in Crossways (1889) in Collected Poems, Macmillan, London, 1965, p. 22f.

- ^ All the references to The Cantos take the form [canto number:page number] and relate to The Cantos of Ezra Pound, Faber and Faber, London, 1975.

- ^ Ezra Pound, Confucian Analects, Peter Owen, London 1979 (1956), p.39.

- ^ Some initial steps in the explication of this section were undertaken by my friend Walter Baumann in his book Roses from the Steel Dust, Orono, Maine, 2000, p. 136f.

-

^

A good and comprehensive review of Pound's Neoplatonism can be found in Peter Th. M.G. Liebregts, Ezra Pound and Neoplatonism, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, Madison, 2004.

Yeats' Platonism, much more on show, has been thoroughly explored. A brief account – although by no means the last word on the subject – can be found in Brian Arkins, 'Yeats and Platonism' in Platonism and the English Imagination, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 279-289.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!