The great survivor

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-03-14 12:42

A nation looks in the glass

There have been six Swiss National Exhibitions (Schweizer Landesausstellungen). The first two, in 1883 (in Zurich) and 1896 (in Geneva), are outside our scope.

From their dates we might think that the second two – in 1914 (in Bern) and 1939 (in Zurich) – both fell at very inauspicious times for the nation: a world war was declared during the course of each one.

In fact, the exhibition in 1914 was a useful platform to demonstrate Switzerland's defensive will, although its Teutonic atmosphere succeeded in driving a wedge between the German and the French speaking parts of Switzerland. To this day the Swiss still jokingly refer to the Röstigraben, 'the rösti trench' between the two language regions. The best jokes have a basis in truth: to this day, political opinion as expressed in referendum results often divides along the 'trench'.

The Landi: in search of the nation

In contrast, the 1939 National Exhibition expressed a moment of national unity and conviction. It was such a success that it had its own nickname: Die Landi– pedants add '1939' but that is unnecessary: in the folk memory there was only one Landi.

Over a period of six months from May to October in the dark year of 1939 it brought together all the wonderful features of the Switzerland of the time: the 'old' Switzerland with its houses and farms, its Alpine grandeur, its folklore and tradition and the 'new' Switzerland with its technological innovations, its transport and modern industry. The country was not Germany, France or Italy, but Switzerland. To every visitor it was clear: this was a country worth fighting for.

All indicators of success show that the Landi was a defining moment for Switzerland, expressing the identity, the unity and the defensive will of its people in those worrying times. Despite the outbreak of war on 1 September 1939 the exhibition stayed open and even hit its visitor record on 15 October, ten days before its scheduled close.

In search of the 'cool'

Against great odds the small country embedded in the middle of the Axis powers survived the war and the hard decade that followed it. By the time the next National Exhibition took place in 1964 in Lausanne the world was glowing in the 'white heat of the technological revolution' and the exhibition showed the dazzlingly optimistic technological world that was to come. The exhibition was a success in its own terms, there were some patriotic elements, too, amongst the spectacle.

But that glowing optimism was soon quenched in the cold waters of a changing world. The attempt to hold another National Exhibition in 1991 – the year of the 700th anniversary of the founding of the Swiss Confederation, no less – fractured in discord: how times had changed.

In 2002 a National Exhibition was held in the area around Neuchatel. In the end the Exhibition obtained its visitors and was counted a success, but the process of organizing and financing it had been an incoherent shambles. Environmentalists protested at the invasive presence of the exhibition in an area of natural conservation. Patriots were annoyed by the 'un-Swiss' tenor of the exhibition: that powerful symbol the Swiss flag was nowhere to be seen and it was quite deliberately banned from a performance to celebrate the Swiss National Day, 1 August. The entry price was extremely high and visitors had frequently to queue for several hours to get in.

The exhibition was ultimately just a stage for 'creatives' to display their wares – much as the Millennium Exhibition in London had been – and expressions of national identity and unity of purpose were not to be found. It was a National Exhibition without the 'nation'.

Even the name was repellent: it had been branded 'Expo.02' in the 'cool' manner of the times. In stark contrast, its predecessor in 1939 had exuded warm, unselfconscious patriotism. That really had been the Landesausstellung, which the people took to their hearts with the affectionate nickname, Landi. In 2002 no one could love the mannered and linguistically colourless label 'Expo.02', a name that would be more fitting on the spine of a ring-file.

There is a plan for a further National Exhibition in 2027 but in your author's opinion it will never take place, certainly not in any form deserving the epithet 'National'. The modern Swiss nation is simply too fragmented and doubt-filled for that.

This may be a good thing, this modern lack of willingness for civilised countries to propagandise their own achievements, to wave their flags and feel patriotic pride. Spectacle has always been a useful item in the totalitarian toolbox, but particularly since the beginning of the 20th century the dictators of the world have brought state-sponsored exhibitions and spectacles into disfavour with the democratically minded.

For this reason many people these days feel uncomfortable with such things, and that is probably a good thing. Let us not forget that the Landi had its own 'Propaganda Committee' from the moment of its conception. Still, for Switzerland in 1939 it worked. We should not 'apply metric tools to imperial machinery' in an attempt to discount its great success.

Die Schweiz, das Ferienland der Völker

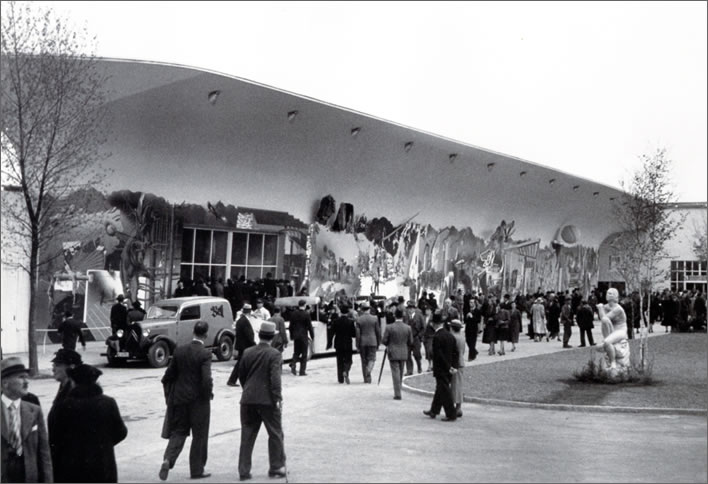

The Landi was built on two sites that straddled the neck of the Lake of Zurich, at the point just before its waters flow under the first bridge and through the city as the river Limmat. On the right bank – the Zurichhorn – a mock village, the Landidörfli was erected containing traditional buildings from various Swiss Cantons. A site on the other bank was given over to the modern Switzerland: technology, work and industry. The two sites were connected with a cable-car across the lake, 75 metres above the surface.

The Landi. Crowds of visitors passing Han's Erni's mural Die Schweiz, das Ferienland der Völker.

Image: Sammlungszentrum, Schweizerische Landesmuseen / Stadtarchiv Zürich.

As part of the 'modern Switzerland' site the Swiss graphic artist Hans Erni, then a 29 year old, was contracted to create a mural for the 'Tourism Wall'. Erni had trained as a surveyor and then as a draughtsman. He had moved into the field of fine arts and became a proponent of modern artists such as Picasso and Braque.

Hans Erni wrote later (1989) of his work on the mural:

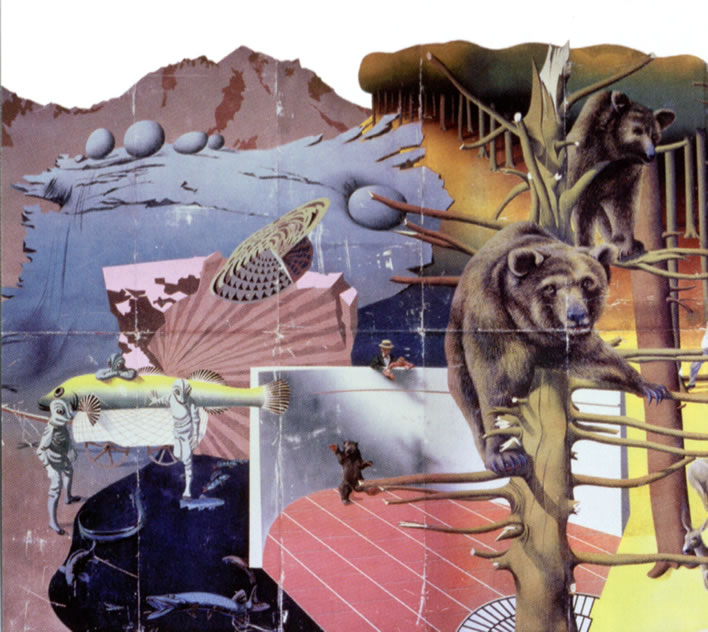

In countless drawings I wanted to visualise the relationship between the changing lives of humans and abiding Nature, to join visually the past and the present. The character of the people – their work, prosperity and culture – should be shown in the course of the succession of the seasons. The early history of the country, its mountains, glaciers, forests, clearances and wildlife, should be expressed in an easily understandable way.

The work was huge: ninety metres long and five metres high. It was built up of 136 panels. Other murals in the exhibition had been painted directly on walls and were demolished with them after the exhibition closed. Its separate panels saved Erni's mural from immediate destruction.

The artist at work.

Image: Sammlungszentrum, Schweizerische Landesmuseen / Stadtarchiv Zürich.

It was given the title Die Schweiz, das Ferienland der Völker – 'Switzerland, the holiday country of the peoples'. The translation is literal and precise, deliberately so, since the title tells us of the purpose of the mural: it was a tourist poster, sponsored largely by the Swiss Federal Railways and the Swiss Post (who, of course, ran the Postbuses). It refers not to 'the people' – that is, the Swiss people – but to 'the peoples' – the peoples of the world.

Erni's own description from 1989 we must treat with caution. By that time he had progressed from tacit communism to open eco-activism. It seems to me that the Erni we hear looking back on his monumental mural is not the young artist carrying out an important contract with a tourism brief. In 1939 it was his task to make Switzerland attractive to foreigners and so he created a ninety metre long tourist poster with all the folklore images you would expect and the trains, buses, roads and planes to get the tourist to it all. Erni's 'changing lives of humans and abiding Nature' appears to be reading something into the mural that is not there.

Nevertheless, whether taken as tourist poster or philosophical statement, Erni's mural is impressive. Judge for yourselves:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hans Erni, Die Schweiz, das Ferienland der Völker, 1939.

Click on the icon to display the image in the main panel. Each image overlaps the previous image by about 50%.

Images: Sammlungszentrum, Schweizerische Landesmuseen

Erni's mural is full of allusions. Here, for example, is the Abbey of Einsiedeln. The striking pair of mountains in the background echoes the Grosser and Kleiner Mythen nearby (but not in this relation to the abbey – the mural is a collage, not a landscape painting). The presence of two ravens on the rooftop in the foreground alludes to the legend of St. Meinrad of Einsiedeln, who was brutally murdered in 861. His killers were followed by two ravens, which led to their capture and execution. The arms of Einsiedeln bear the image of two ravens.

Postwar life in a shed

Unlike some of the other murals at the Landi, Erni's mural survived the demolition of the exhibition. Switzerland had other things on its mind during the years after the exhibition. The mural was dismantled and stored in a railway shed belonging to its owners, the SBB, the Swiss Federal Railways. Out of sight, out of mind for fifty years.

The panels of Erni's mural in a railway shed at Rorschach (?) in Switzerland, their home for nearly 50 years.

Image: Sammlungszentrum, Schweizerische Landesmuseen / Robert Brändli.

In 1990 the 136 panels were donated by the SBB to the Swiss National Museum in Zurich. The year before, the entire mural had been shown in the open at the Transport Museum in Lucerne, in which the Hans Erni Museum is located, and a couple of years later at the National Research Exhibition Heureka in Zurich, also in the open air. After that it disappeared from public view for more than a decade, stored in the Swiss National Museum – a step up from a railway shed, at least.

An object of interest

By the end of its exhibition in 1991 Erni's mural was showing its age. After six months in the open air in 1939 it had been assembled, dismantled, transported, stacked, re-assembled and exposed to the elements, all multiple times. After coming into the possession of the Swiss National Museum it was at least now packed appropriately for transport and stored in appropriate climatic conditions.

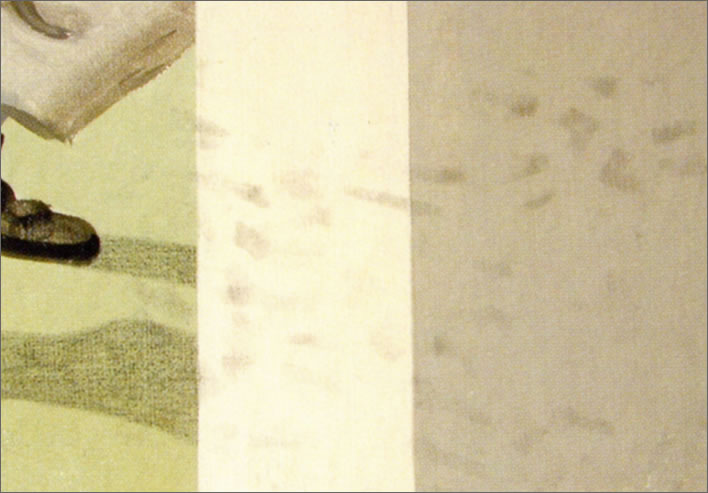

Examples of damage to the panels of the mural.

Image: Sammlungszentrum, Schweizerische Landesmuseen

The mural had been painted on plywood panels, the layers of which had started to split apart at points. Long cracks had appeared in the panels. Parts of the upper wood layer had separated from the base, corners and edges had been damaged. The painting itself had been scratched and flakes of paint were breaking loose or had fallen off. The mural had been painted with 'casein tempera', a mixture of pigment and milk protein. The paint layer had separated from the foundation at points and had formed large blisters and powdery patches.

What to do? Arresting the decline of 420 square metres of painting was a big project. Furthermore the task of re-attaching the paint layer was tricky. The motto in art conservation seems to be: do it wrongly and you make it worse. The conservation department of the Swiss National Museum set out on a decade-long search for a suitable glue to do this job.

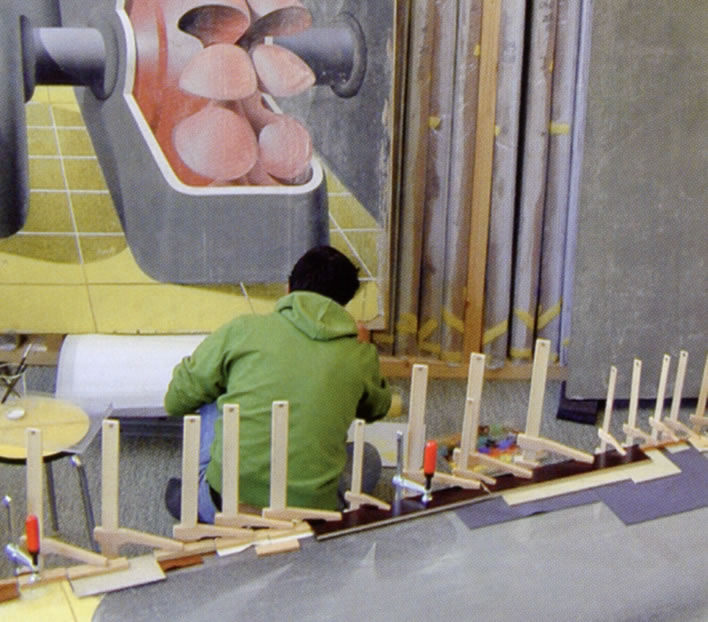

Confronted with the problem, the EMPA, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology and the specialists of the National Museum developed a special glue based on an extract from an algae to use to re-attach the matte paint layer to its base on the Erni mural.[1] The development took twelve years of painstaking and careful work. Only when that was completed could work start on the mural itself. The only thing missing now was money.

Conservation work in progress in the Swiss National Museum.

Image: Sammlungszentrum, Schweizerische Landesmuseen

The development of the algae-based glue had already cost 520,000 Swiss Francs, a sum that had been covered by grants from two foundations. The conservation work itself would cost another 850,000 Francs of which the National Museum could provide about a quarter. Hans Erni himself created a 'facsimile lithograph' specially for the occasion in a limited edition of 750 for sale at 750 Francs each. The lithographs were a sellout [2]– attesting to Erni's broad popularity in Switzerland – and brought in 565,000 Francs. A single anonymous donor contributed a further 70,000 Francs.

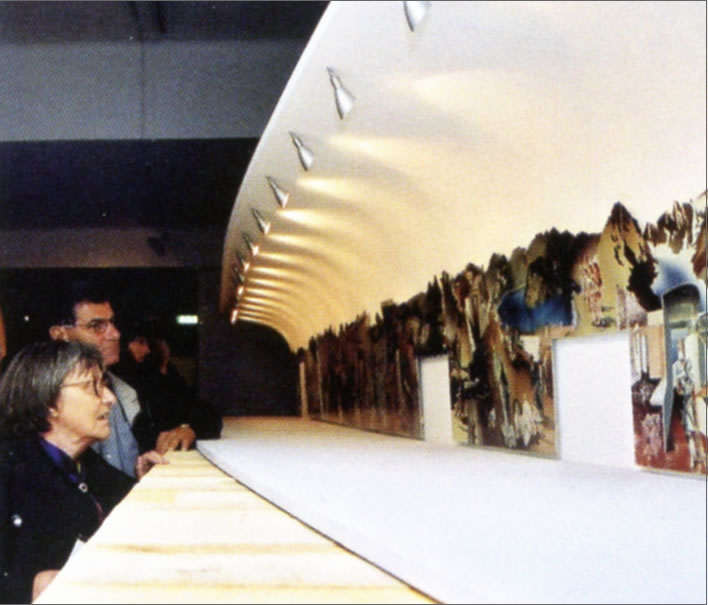

A handy exhibition-size model of Erni's mural.

Image: Sammlungszentrum, Schweizerische Landesmuseen

In the autumn of 2003 the National Museum put on an exhibition to launch the conservation project. Three years and 52 person-months of work later the conservation project was completed in 2006.

If private people and foundations are prepared to dig into their pockets and finance the conservation of Ern's mural, costing well over a million Swiss Francs, that is their choice. It attests, as we said above, to the popularity of Hans Erni's work and particularly to a sentimental attachment to that time in 1939 when Switzerland was a nation with a widely shared self-belief that was still intact. But apart from the sentimental gesture, what was the point?

What now?

Now the sentimental requirements of conserving this moment of history have been fulfilled we have to ask: what now?

It is hard to imagine that the mural will ever be displayed again in its entirety. It will never be exposed outdoors to the elements again and suitable indoor walls 90 metres long are not common. It looks as though the mural is condemned to remain in a museum store for ever. Groups of few panels may be shown here and there, but the integrity of the full size work – the passage of the seasons, the rhythm of geography and human activity – will never be seen again.

Even if a place were to be found, before the full mural could be shown it would surely require a full restoration, a task that would be much more expensive than the conservation. Perhaps it would even be cheaper to replicate it with modern materials. It would certainly make a fine feature in a large mainline station in Switzerland, for example, taking it back to the institution that commissioned it, the Federal Railways. What a wonderful visiting card for foreigners passing through! What a contribution to selfie-world!

True, it would have to be out of reach or protected in some way. In 1939 millions of people walked past it without incident (as far as we know). No one felt the need to violate it in some way to make a point about something or other. After 70 years of social progress we have sprayers, taggers, protesters and vandals of all types. Keeping it safe in a public space would be quite difficult.

But something that could be done immediately is the photographic recording of the panels and the creation of a zoom-able and pan-able internet presence for the mural. This would give easy access world-wide to that Swiss moment in 1939. It would be good for Switzerland, for the Landesmuseum and Erni's memory.

There are no downsides. The implementation would cost very little, even if, as a special addition, the damage to the image and the fading were to be improved digitally. True, the special sense of standing in front of the original mural with its 'aura' (a nonsensical concept of the cultural critic Walter Benjamin) is no longer there. But if we cannot have that, then any sort of easy digital access is much, much better than spending the next hundred years stacked in the darkness of an environmentally controlled bunker.

The author of this piece would like to thank the Sammlungszentrum of the Schweizerische Landesmuseen for their help. The opinions expressed in this piece are entirely his own.

References

- ^ This wonderful stuff is called JunFunori® and would make a perfect present for the art conserver in your life. When you rush out to get it don't forget your platinum card, though: it costs CHF 32,000 for 400 grams (a jamjar full).

- ^ I would like to show you this lithograph, Friedenswunsch 'A wish for peace', but as is quite normal for Erni's works, it has no internet presence and is therefore reserved for the eyes of the 750 who paid for it.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!