Portrait of the age

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-08-20 10:28

In the spring of 1769 the Roman artist Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787) received the most important commission of his life. It came from Maria Theresia (1717–1780), Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. Her sons the Emperor Joseph II (1741-1790) and Archduke Leopold (1747-1792) would be in Rome in March and he was to paint their portraits.[1]

Batoni had made a name for himself as the go-to portrait painter for aristocratic travellers passing through Rome on the Grand Tour, many of whom were English. Travellers wanted a souvenir of their time in the Eternal City and Batoni gave it to them. He even kept a stock of canvases with prepared backgrounds containing views of landmarks such as the Colosseum, or miscellaneous bits of sculptural relics – the glory that was Rome and all that.

Here's an example of Batoni's everyday work, a portrait of an unknown man from around 1765.

'Look where I've been!'. A young man in his finery and with a vacuous half-grin pointing at some generic Roman stuff: books (e.g. 'Lives of the Artists' – note the artful slip of paper in the bottom book, hinting that it has actuall been read), an inkpot with two pens, a copy of some relief or other, a statue of Minerva in the background. The view between the columns suggests Vesuvius(?). At least the handy little travelling dog looks interested. We don't really need to know who the subject was because the portrait tells us nothing about him: it's an empty snapshot.

The portrait is well executed – Batoni was a skilful craftsman who gave his customers exactly what they wanted, a quality souvenir of their time in Italy. The painting is, however, meaningless for anyone but the subject. In a gallery we would pause before this painting, look at the subject's face for a few seconds, note the adoring dog at his feet, the Classical bric-à-brac on the ornate table and move on to the next painting, completely unmoved.

It's a snapshot just like the millions of tourist snapshots taken with modern cameras: the sort that strike dread into the hearts of those facing tedious hours looking at other people's holiday snaps, scenes which are only interesting to the people in the picture. There are millions of people walking around with smartphones loaded with such stuff.

Such snapshots are what the travellers wanted and giving customers what they wanted had given Batoni the reputation of being the best portrait painter in Italy. He worked quickly, was reasonably priced and was set up to accommodate the passing trade.

An unfinished self-portrait of Batoni intended for the collection of artists' likenesses in the Uffizi Gallery. In his last years Batoni fell on hard times. He died insolvent in 1787. Despite being unfinished the self-portrait was accepted in the collection after his death.

Maria Theresia's golden boys

Batoni was not going to get away with routine work for the Habsburgs, especially Joseph, arguably the greatest meddler and know-it-all in the history of the world. The Austrian 'Empire of Paperwork' swung into action. Batoni, used to his somewhat intellectually limited Grand Tourists and various local nobility who just wanted an impressive portrait in their finery, must have been quite shell-shocked by this bureaucratic bombardment from the Viennese and their Roman representatives. When Joseph and his brother Leopold arrived in March the meddling could only get worse.

It seems the idea of having Batoni paint the pair was initiated in Vienna, before Joseph had set off. Commissioning the paintings was Maria Theresia's idea and she would be paying for them. The original plan was that Batoni would paint a portrait and a copy of each of her sons. She would get the portraits of them both, Joseph would get the copy of Leopold's portrait and Leopold the copy of Joseph's portrait.

Every mother of course has a special place in her affections for her children, but for Maria Theresia the two boys were very special indeed. Joseph was the boy whose birth secured the Habsburg descent at a time when the dynasty was faced with collapse. Despite their increasingly fractious relationship as rulers, Maria Theresia always adored him.

Leopold was the second son who was not only the 'spare' to Joseph's 'heir' but became the loins of the next generation of the Habsburg succession. Joseph's breeding days had been unsuccessful for a variety of reasons and the family relied on Leopold to secure the succession – which he did many times over. Maria Theresia learned that Leopold and his wife had also produced a boy, their second child, while she was in her box in the Burgtheater in Vienna. Legend has it that she stood up and cried out in joy to the audience in Viennese dialect Der Poldl hat an Buam, 'Leopold has had a son'. It was such displays of spontaneous and heartfelt emotion that gave her, the 'Mother of Austria', such a secure place in the hearts of her people. There can be no doubt: these two were her special boys.

The brothers were in Rome for 15 days. We believe that Joseph had seven sittings in Batoni's studio and Leopold six. It appears that the idea for a joint portrait may have crystallised out during that first session. The details were worked out in discussions between Batoni, the brothers and the Imperial Ambassador in Rome. Joseph refers to the project as 'my portrait' in various documents from the time, but that may just be Joseph's monumental ego expressing itself.

If only we had a record of the discussions that took place between the artist and his subjects during the commissioning of this work! Batoni was not a mind reader and would not presume to know his sitters well enough to set them in scene – he had to rely absolutely on their instructions. Which is just another way of saying that this is Joseph's portrait, not Batoni's. As it happens, since the brothers themselves, the Viennese and Florentine courts and the Embassy in Rome were all involved there is an unusually large amount of documentation available on the project – the Empire of Paperwork doing what it does best: scribbling. From the only person who really mattered, Batoni, we have nothing.

These two Austrian subjects were anything but simple tourists and required Batoni in this portrait to construct a book that told everyone who they were. It was not a simple book, either. It was a programmatic book, a manifesto for the coming age that would be read with great attention by their contempories.

The brothers left Rome on 30 March 1769, leaving Batoni to complete the work. The artist had little peace and quiet in which to do this: the portrait of the two great nobles, who had been treated almost as rock stars during their stay, received a stream of visitors in Batoni's studio whilst he worked on it. He also had to contend with frequent visits and monitoring by the delegates of Maria Theresia.

Every Habsburg project had to be top-down micro-managed. Batoni, his customer skills honed by long practice, seems to have kept his handlers happy. After about two months' work he was able to dispatch the painting on 17 June to Leopold's court in Florence, where it went on show for three days before being sent on to Vienna.

Far from being the routine Grand Tourist portrait, Batoni, under the guidance of the brothers and with them frequently looking over his shoulder, turned out a magnificent composition that was anything but meaningless. Unlike the snapshots that were his bread-and-butter work, this painting demanded every painterly skill in his possession. The hand of history was on Batoni's shoulder and he delivered a painting which marks a turning point in the history of Europe and is arguably one of the the most important images of the 18th century.

Here it is:

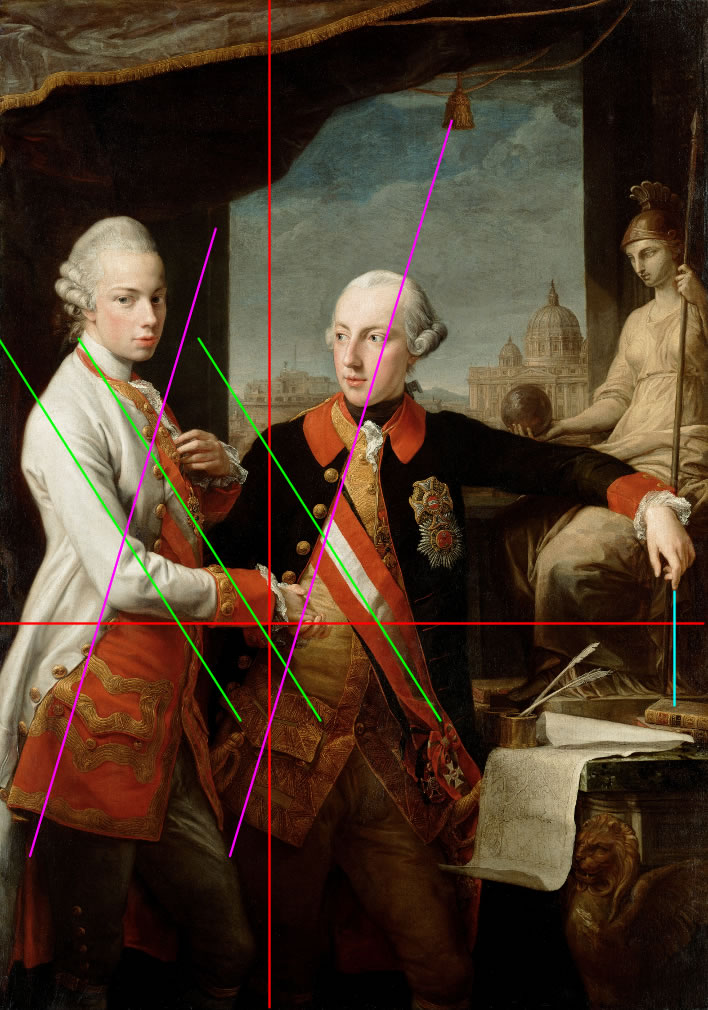

Pompeo Batoni: Kaiser Joseph II. (1741-1790) und Großherzog Pietro Leopoldo von Toskana (1747-1792), dated 1769, canvas, 173 cm x 122.5 cm. Image: Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie Inv.-Nr. GG_1628.There are many copies and variants in existence.[2]

You don't see this in a gallery and then walk away after 30 seconds.

Batoni, his bread-and-butter work the single posed figure, now had to represent in paint the complex dynamic between these two young rulers. Rank had to be taken into account: Joseph, the 29 year-old Emperor (although still co-regent with his formidable mother) most definitely takes centre stage in the painting. He is the figure around which everything else is grouped. His brother Leopold, six years younger and 'only' at this time the Archduke of Austria and Grand Duke of Tuscany appears to be pushed to the side of the composition – except that he appears taller and glows white against the gloom of his background. In that sense he is not a subordinate figure in the composition – if anything it is to him that the eye of the viewer is drawn first. Batoni, it has to be said, achieved a remarkable balance in the representation of a theoretically unbalanced group.

Composition

Let's look briefly at the structure of the portrait.

The brothers' handshake – what a clever pose! – is located almost exactly at the horizontal and vertical 'golden sections' of the painting (red lines). The unity of the two young men is on public display.

Joseph's massive ego, his feeling of superiority to the rest of the human race in anything he did was understandably a hard trait for the younger and more introverted Leopold to live with – actually for anyone to live with. There were arguments over responsibilities, inheritances and money. Joseph even intervened in the education of Leopold's children. Leopold's comments made in his personal journal during his visits to Vienna in 1778 and 1784 about Joseph are scathing and utterly contemptuous. After the catastrophe of Joseph's ten-year reign, Leopold felt it wiser not to be present at the deathbed of his now universally despised brother. The handshake represents an outward show of harmony where none really existed, even in 1769.

Given the static nature of most of Batoni's other society portraits the dynamism of this painting is remarkable. Leopold seems to be almost in movement. If we trace the main structural lines of the painting (green and purple) we begin to see how artfully the painter achieved this. Both figures are angled, which gives the overall sense of dynamism in the painting. Leopold's coat is swept back, as though he has just turned to Joseph. Even the tassel of the cloth canopy is part of this dynamic structure, almost an anchor point.

Joseph is gazing at something outside the picture on the left, but not at the same point as Leopold. The differing directions of view, at first slightly unnerving, have an inner logic that Batoni clearly understood: having the pair look at each other with hands held would have turned the painting into a wedding portrait, whereas a challenging eye-contact with the viewer with heads in semi-profile would have just made them look shifty. Batoni earned his reputation here: the differing viepoints give the painting a lively feel that transcends conventional, static poses.

Leopold, pale and interesting, is looking not quite directly at us. The dark background behind him makes his white coat, pale face and white periwig glow for our attention, even though he is on the edge of the painting. He is standing with his right side to us and so his white coat shows us no orders or decorations.

His left hand hovers over his heart, almost pointing, its delicate fingers toying, not quite absent-mindedly, with the lace ruffles of his shirt, leading the observer's eye to the pendent of the Order of the Golden Fleece just below those elegant fingers, hanging over the Austrian sash for us all to see. The gesture of pointing at the heart is a long established symbolic expression of loyalty and devotion. Contemporary viewers would have noticed this immediately.

Joseph, as older brother and Emperor, is in the centre of the composition. His dark coat stands out in front of the pale background of the 'window' behind him. Batoni's use of light and shade in the background to the two brothers is absolutely masterful.

Despite the darkness of his coat and his position in the midground of the painting he takes up space across the centre of the scene and dominates the group – his left arm outstretched and his right arm behind Leopold, attaching him to the group. There is no visible gap between the two figures.

Joseph is leaning insouciantly – quite cheekily in fact – on the thigh of a seated statue of the goddess Roma. We catch a glimpse behind his head of the bow of the military-style hair plait in which he liked to wear his hair. Contemporaries will note that he is wearing the single-roll periwig popular with officers of the time. The military man and his military goddess.

You are what you dangle

His rank is evident from the orders he wears: the great stars down the lefthand side of his jacket are the Grand Cross of the Military Order of Maria Theresia and the Royal Hungarian Order of Saint Stephen – Austria and Hungary united, the great ancestral Habsburg lands. The pendants of these orders are on his sash. We also see his pendant Order of the Golden Fleece dangling from a buttonhole of his waistcoat. Both brothers are wearing their 'uniform swords'.

These trinkets were of immense importance to the 18th century aristocrat. Batoni knew the importance of such things to his customers and used his considerable skill with detail where it mattered.

Joseph is holding his brother's right hand in his, perfectly positioned by Batoni at the horizontal and vertical golden sections of the painting. This fact is not just a compositional device: it is a statement. Leopold's hand is cradled in Joseph's. It is not really a handshake between two equal partners.

The brothers

The faces of the two young men can only be those of brothers – two peas in a pod. There is only the slightest trace of the 'Habsburg lip' that was such a characteristic disfigurement of the genetically defective earlier members of the family. The careful rendering of the brothers' lips may be intended to make this point – or it might just be Batoni showing off his famous skill in delineation.

He appears to have used Bernard van Orley's trick to reduce the size of the lower lip by painting their mouths slightly open. The feature was slightly more pronounced in Leopold.

Although only visible here for those that have eyes to see, the genetic defect is still there and would surface again in Leopold's eldest son, Franz II/I and be passed in turn – with a vengeance – to his eldest son, Ferdinand I. For the moment, in this portrait, the two Habsburg men appear as the golden boys of Europe.

We should also note Joseph's pale blue eyes, which became one of his trademarks during the short time in which people still liked him:

[Joseph had] eyes of such a beautiful blue that in Austria it was fashionable for a time to wear clothes of that colour. In all the shops it was known as 'emperor's-eyes blue' (Kaiseraugenblau)[3]

Joseph's gaze is distracted, introspective, even. Batoni has added quite strong highlights to Joseph's eyes, which make them sparkle. They are much livelier than such pale eyes in a pale face would otherwise be – this is an artist giving us a masterclass in bringing out the best in a sitter's face.

That remarkable, distracted gaze of Joseph's is striking. He is the dreamy thinker in the midground of the portrait. Is it intended that Leopold, the bright figure in the foreground looking out of the canvas, has a 'mediator role' between his pensive, distracted brother and the world?

Holiday reading

Joseph's left hand points downwards – the index finger is definitely pointing, albeit in a relaxed way – at two volumes on the table on the right of the picture (blue line on the structure image). The volumes are not just generic books. Batoni, famed for his mastery of accurate detailing in his paintings, has given them clear titles: De l'esprit des loix, Montesquieu's seminal work of the Enlightenment. The work, at first censored, had finally been legalized in Austria about 15 years before.

Under the books is a city plan of Rome and upon that an inkpot with two quill pens. The two pens share the same inkpot, the two brothers writing from the same source. We saw the inkpot and the two quills in Batoni's portrait of the unknown gentleman, although in that painting the quills were white and black.

Dea Roma, wisdom and arms

The goddess over whose thigh Joseph has so casually draped his arm and on whom he is therefore relying for support is Dea Roma, the goddess Rome. For this figure Batoni has made a close adaptation of the statue of Dea Roma in the Piazza del Campidoglio, a landmark which the brothers may have seen. Dea Roma was originally the goddess Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, arts and crafts, the Roman parallel to the Greek goddess Athena. She is also a warlike goddess, as her helmet and spear shows. Joseph, the happy though ineffectual warrior, would feel comfortable resting on her thigh.

The statue of the goddess Dea Roma, part of the Fountain of Dea Roma in front of the stairs that lead up to the Senatorial Palace in the Piazza del Campidoglio on the Capitoline Hill in Rome. The square was designed by Michaelangelo, who completed the design for the stairs. The porphyry statue of the seated Dea Roma is actually a statue of the goddess Minerva from the time of Domitian (51-96, emperor 81-86 – yet another 'enlightened despot'), who regarded her as his protectress. It was placed in 1593 in a niche in the centre of the fountain group.

In Batoni's version Dea Roma is holding a globe of the Earth in her right hand and the spear/sceptre in her left, the opposite way round to the original, thus bringing her spear to the front. It can be no accident that Joseph's left hand almost seems to grasp her spear, which is resting on the pediment just behind Montesquieu's books: force based on law, indeed!

Batoni does not distract the viewer from the importance of his sitters by over-rendering this powerful and potentially very solid figure – he has left her pale, almost a wraith, an idea of justice. He has also extended the thigh of the goddess beyond its normal proportions in order to give the Emperor Joseph something to lean on, but so skilfully that the distortion does not disturb us.

Through the window

Returning to the 'window', we note on closer inspection that what we are shown is not a real Roman cityscape, but an artfully constructed juxtaposition of two distinct views: on the right St. Peter's Basilica viewed from the east and on the left Castel Sant'Angelo, also from the east. Artfully constructed because the view as it is represented here is impossible in reality. These two buildings are not close enough to be painted as neighbours and even if they were, their positions would have to be flipped horizontally to match the view in the painting: Castel Sant'Angelo would be on the right and St. Peter's Basilica on the left. In their individual aspects from the east, however, they are completely consistent.

The 'window' is not really a window because it has no appreciable effect on the incident light in the room – it's more like a mural. We barely notice this inconsistency behind the dominant foreground.

The normal tourist would have been content with a standard boilerplate view of the Colosseum for a portrait, which we see in many other portraits painted by Batoni. In fact the Colosseum was used in an early draft of the painting, but the final cityscape turned out to be completely different. Why use these two particular buildings as a representation of Rome? Because they are laden with symbolism for our imperial travellers.

St. Peter's Basilica is, of course, the heart of the Vatican and Catholic christianity. We should note that that we are shown the Basilica, not the Vatican Palace – the centre of faith not the centre of power. To the readers of our portrait book the image of St. Peter's says: Defender of the Catholic Faith. There is perhaps a greater symbolism that we shall see later when we discuss Joseph's involvement in the Papal Conclave during his visit.

Castel Sant'Angelo, also known as Hadrian's Mausoleum, is the resting place of a number of Roman emperors – not just Hadrian but also Marcus Aurelius, the stoic philosopher-emperor. This is an 'imperial' monument, but not just of one particular triumph or one particular emperor but of the concept of Roman imperial power in itself. It is also a memorial of the 'good', the noble, ancient Rome, unlike the Colosseum, for example, with its aftertaste of bread, circuses, excess and imperial decline. To the educated readers of our portrait book the image of Castel Sant'Angelo says: The glory that was Rome.

Or perhaps it says more. Castel Sant'Angelo was also the fortified refuge used by the popes at times of danger. Although St. Peter's and the Mausoleum are not close neighbours, the route between the adjoining Vatican Palace and the fortress is only about 800 metres along a special and direct escape route, an elevated path called the Passetto di Borgo. The use of Castel Sant'Angelo as a papal refuge was not a distant historical fantasy: it had been used for that purpose on several occasions.

Apart from protecting the occasional pope on the run, the fortress was a handy prison for the disfavoured, such as Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571). There were others, too, whom we might more easily count among the enlightened: Giordano Bruno (1548–1600), burned at the stake as an heretic; a number of troublesome humanists in the 1460s, among them Bartolomeo Sacchi (1421-1481), (known as 'Platina'), who was locked up and tortured for a couple of years and Giulio Pomponio Leto (1428-1498), who was also imprisoned and tortured. We shall slide over the details of the horribly brutal executions there of the Cenci family in 1599, which turned the young Beatrice Cenci (1577-1599) into a folk hero in Italy.

Whether the tour guide had informed the two noble visitors about these darker shadows – mostly cast by the exercise of papal authority – on the reputation of the Castel Sant'Angelo we do not know. Perhaps Joseph and Leopold are juxtaposing papal and imperial authority; perhaps they are juxtaposing brutal papal intransigence with the sacrifice of the humanist martyrs of the Italian Renaissance. Or perhaps both, which is my feeling.

The pair were certainly well educated, even though it is unlikely that their Jesuit teachers made much of the Italian humanists or of the Cenci family. Given their Enlightenment passions, which they are currently showing us in this painting, it is scarcely credible that they did not know this background. They had prepared carefully for their visit with their list of things to see. It would therefore be a surprise if they managed to visit Castel Sant'Angelo without hearing of these dark happenings. To the well-read readers of our portrait book the image of that building may say: The dark road from bigotry to Enlightenment.

Now that we understand the symbolism of the various components of the painting we can appreciate clearly the significance of Joseph's position in the composition. He it is who occupies the major ratio and who is surrounded with all the symbolic objects we have discussed: Montesquieu's work, Minerva and the two buildings symbolising religion and empire that frame his head.

Leopold stands aside, his right hand in Joseph's, his left hand pointing to his heart. This is Joseph's painting and Joseph's manifesto – with a walk-on part that allows Leopold to demonstrate his loyalty to his elder brother. Joseph's gaze is detached, imperial, careless of the viewer; Leopold, on the other hand, is looking out almost directly at us, for he is making a statement that he wishes us to see. The handshake is not so much a display of harmony as a display of submission, a submissive gesture intended for us all to see.

Wandering around Rome

Students of history tend to divide naturally into two groups. The 'stuff happens' group generally sees the figures of history stumbling around doing their best to cope with a barely understood Zeitgeist. The 'machinations' group believes that whatever happens, there is usually someone in the background pulling the strings. My temperament puts me in the first group – unless Habsburgs are involved, in which case, without solid evidence to the contrary, I am firmly in the second group. And so it is with the brothers' trip to Rome.

Why did Joseph and Leopold undertake a journey to Rome just then? The journey was arranged at extremely short notice. Why the haste to chase off to Rome and see the sights? We note merely that Clement XIII had died suddenly on 2 February 1769 and a Papal Conclave to elect his successor was convened on 15 February. It lasted until 19 May 1769. Joseph arrived in Rome on 15 March. Given the time required for news to carry and the days of travelling needed to get from Vienna to Rome we realize how rapidly the Habsburg administration responded to the news from Rome in order to get Joseph there by mid-March. Something was afoot.

Some of the paperwork from an earlier, abandoned journey two years previously was recycled, in particular a report on the papal state. Joseph being Joseph – the useful, the practical, the inquisitive, thirsty-for-knowledge Emperor – he drew up a long list of 'things to see'[4], both in Rome and on the journey. Joseph would 'do' Italy and Rome, storing the results in that part of his brain reserved for all the things he knew that no one else did. Vesuvius had to be ascended, for example (which he did on 30 March)[5]. It's a typical Habsburg self-improvement list from the Empire of Paperwork written by Emperor know-it-all in his own hand.

Leopold would travel to Rome from the ducal residence in Florence. Joseph would depart from Vienna, travelling 'incognito'.

Joseph's 'incognito travel' is one of the more entertaining aspects of his life.[6] We haven't space here to go into the many lengthy journeys he made, each planned in immense and minute detail, but we have touched upon them briefly elsewhere.

He travelled under the pseudonym 'Count von Falkenstein', so that he could see for himself things as they really were. Joseph's pseudonym immediately became the worst kept secret in the Habsburg empire. Despite this, Joseph kept up the pretence of travelling incognito, presumably so that he, the man of the people, could affect the common touch. He seems also to have enjoyed the consternation it caused among his subjects: having the Holy Roman Emperor turn up unannounced at your inn, castle or palace in the guise of a humble count – 'No fuss, no fuss!' – caused much discomfort in those hierarchical and respectful times. The underlings threw on their finery to greet their Emperor but felt ill at ease when the man of the people turned up in his travel attire. But then, one thing that Joseph really enjoyed was the psychological advantage he gained from wrong-footing other people.

So it was in Rome. 'Count Falkenstein's' carriage was greeted by heaving, cheering crowds – 'No fuss, no fuss!' – but what a blow it would have been had he really arrived unnoticed![7] During his time in Rome he walked through the city almost unattended, with crowds following him everywhere.

Gatecrashing the Papal Conclave

And then he 'happened to' turn up at the Vatican just whilst the cardinals were choosing the next Pope. They were supposed to stay locked away until they had reached their decision, but for the Holy Roman Emperor an exception was made and the seals were broken on 20 March to allow Joseph to enter and make a short, unexceptional speech.

However, this was no ordinary Papal Conclave. It was one of the most critical moments in the history of the Catholic Church – and in the cultural history of a large part of Europe. More than anything this conclave was the gateway to the Enlightenment, because it led to the suppression of the Society of Jesus – the Jesuits – throughout Europe.

The Society was founded by Saint Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556) in 1534-1540 and became a major player in the Counter-Reformation. The discipline and sense of vocation of of 'God's Soldiers' led to their deep penetration into nearly all aspects of life in Catholic countries. The Jesuits did not recognise a separation of church and state – the state was an arm of the church. In the deeply Catholic Habsburg Empire they had an almost exclusive hold on education at all levels, they were responsible for the censorship of all printed materials, whether academic or everyday.

The success and determination of the Jesuits aroused resentment and distrust and a number of countries moved against them. They were ejected in 1759 by Portugal, in 1762 by France, in 1767 by Spain and in 1768 by Naples, Sicily and the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza.

Nevertheless, in the late Pope, Clement XIII, the Jesuits had a strong ally: he had done his best to support them against the secular and religious forces ranged against them. He died on 2 February 1769, leaving the issue unresolved. A proposal for a general ban on the Jesuits would be the top document on his successor's desk, making it absolutely critical who that successor was. The Conclave took three months to choose that successor.

The cardinals pondering the choice between pro- and anti-Jesuit factions may not have seen it quite this way, but the effect would be that an anti-Jesuit Pope would open the Catholic countries – among them particularly the Habsburg Empire – to the Enlightenment ideas that were causing so much progressive change in the Protestant countries. A pro-Jesuit Pope, on the other hand, would slow down the progress of the Enlightenment in Catholic countries, possibly for decades. Education, science, the new technologies and the new learning would remain in the Jesuit stranglehold.

Joseph's address to the Conclave was on the surface innocuous. He simply wished them well in their deliberations and toured the building, marvelling at the sights. He spoke with a number of cardinals. Depending on whose account you believe he made his feelings about the outcome he desired known, albeit indirectly. For Joseph there could be only one outcome: ban the Jesuits. No one can find Joseph's fingerprints on that decision – which is actually how it should be. He wore gloves.

However, we just need to ask ourselves: all that last-minute rush, travel and expense for a few harmless sentences at the Conclave and a painting? Really?

The Jesuits and 'that book'

For the last 20 years Joseph, who saw himself as a figurehead of the Enlightenment – at least as he understood it – had watched the battles that had gone on in Austria against the Jesuits and the deep roots they had put down in the state. The Church, the schools, the universities were dominated by the Jesuits. The boys and men they had educated became their roots into every corner of Austrian society. But there was a particular case that Joseph had observed at first hand. The title will be familiar to the reader: Montesquieu's De l'esprit des loix.

The book was a monumental comparative review of systems of government around the world. It was a work of 21 years of heavyweight scholarship the value of which was recognised immediately by rulers, administrators, writers philosophers and thinkers throughout Europe.

Before this book appeared the laws and customs of any particular country seemed self-evidently valid to its inhabitants. Travellers might find some things odd, but 'when in Rome' etc. Enlightenment satirists such as Voltaire and Montesquieu himself often used the conceit of a journey into distant foreign parts to point out the foolishness or arbitrariness of particular rules.

In De l'esprit des loix Montesquieu introduced an empirical basis to political philosophy and sociology, quite in the spirit of the Scientific Revolution that was already proceeding apace. The works of Isaac Newton (1642-1727) among many others had delivered an empirical understanding of the physical world. Montesquieu in 1748 delivered an empirical understanding of government and administration: reason should now rule in public affairs as much as it did in science. No ruler or administrator wishing to claim to be 'enlightened' could do without reading it.

Montesquieu published the book in 1748, anonymously, because he knew as a satirist and essayist perfectly well what to expect. The book had no chance of passing the censors. In 1751 it was put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the infamous index of banned books maintained by the Catholic Church, principally because the Society of Jesus believed that it had been attacked in certain parts of the book.

De l'esprit des loix arrived in Vienna in 1750, when the Jesuits were still playing the main role in censorship. Accompanied by a campaign of misrepresentations, misquotations and general defamation of Montesquieu, the book was banned in the Austrian Empire. One respected commentator, Joseph von Sonnenfels (1732-1817), who would become one of the great Enlightenment luminaries of the Austrian Empire, noted that it would have cost you your position and happiness had you mentioned that you had leafed through L'Esprit. Sonnenfels also admitted that he had had access to the book and so had been able to check the 'quotations' from it that the Jesuits had put forward in their arguments for the continued banning of the book. Our jaws do not drop open in surprise that the quotations turned out to be either taken completely out of context, mangled or simply just made up.

For any rational, educated person the situation was untenable. Montesquieu's book was an extensive and well-documented treatise on political theory that was the culmination of about 20 years of study by one of the great thinkers of the age, a book that would, within months of its publication, be recognized throughout the western world as a model of its kind. The fact that the dissemination of such a work could be suppressed in its entirety by a religious order just because it took exception to a few passages (in volume 4, chapter 6, actually) was emblematic for the malign influence that the Jesuits had on the entire cultural life of the Catholic states Europe – and above all the Austrian Empire.

Despite Maria Theresia's Censorship Commission under the leadership of the redoubtable Gerhard van Swieten lifting the ban on the book in 1752 the determination and organization of the Jesuits pursued a series of delaying tactics to keep the book banned until finally, in March 1753, even the devoutly Catholic Maria Theresia's patience was at an end and she ordered that L'esprit should published. Van Swieten's battles with the Jesuits continued for another six years until 1759, when Maria Theresia nominated him as President of the entire commission and the Jesuits were rendered powerless in censorship matters. However, that was just one battle in a long guerilla war.

The young Joseph, an 18 year-old in 1759, had watched all this from the sidelines as a teenager. Ten years later he was in Rome as Emperor and co-regent at this pivotal moment in history. Was he just there to see the sights and have his portrait painted?

That critical Papal Conclave would elect an anti-Jesuit Pope, Clement XIV (1705-1774, Pope 1769-1774), who would four years later, in 1773, suppress the Society of Jesus entirely. The Austrian government now had complete control over the education system and all the money and infrastructure that had belonged to the Jesuits. It could also implement its own register of banned books. The transformation of the Austrian Empire and all the other Catholic countries of Europe started here. They would never catch up the Protestant countries, but at least a breakthrough had been achieved and they had started out on the road to being modern, secular states.

Batoni's portrait of the two Enlightenment rulers could be considered to be also a portrait of a book, Montesquieu's De l'esprit des loix, to which Joseph is helpfully pointing, for the slow ones among us. The painting was, in 1769, a great visual, programmatic, manifesto.

The Enlightenment and all that

We moderns have lost touch with the original meaning of the movement that was labelled the 'Enlightenment'. That radiant label allows us to ascribe all sorts of pleasant features to it, all those features that we happen to hold to be desirable or 'progressive'. We have on this blog occasionally protested at such misinterpretations: in its original form the Enlightenment had nothing to do with democracy or human rights or individual freedom, it was then almost a perfect synonym for 'secularism' – and more specifically the separation of church and state.

Montesquieu was the father of the idea of such a separation, which is another telling argument for the importance of his book's presence in the painting of the two rulers. The goal of the Enlightenment thinkers was to remove the influence of organized religion from secular life. Voltaire's immense powers of ridicule were directed – some would say obsessively – against organized religions, whether Catholic or Protestant. Immanuel Kant's much misunderstood essay What is Enlightenment?[8] rests on an argument against religious bigotry and thought-control by organized religion. In religious matters, the 'enlightened person' should think for themselves. However, when it came to Kant's patron, the despotic Frederick the Great, then one had simply to 'obey' – thinking for yourself was no longer required of Prussians. In Kant's essay we find no trace of human rights or democracy, simply an argument for the rationalisation of religious thought.

When Joseph II and his followers flaunt his Enlightenment credentials we must understand the term 'enlightened' as it was meant then: a detachment from religious interference and the creation of a secular state based on the rule of law.

In Batoni's portrait the image of Joseph II, the personification of the young Enlightenment ruler pointing at De l'esprit des loix, is placed between St. Peter's Basilica, the symbol of the Roman Church, and the Castel Sant'Angelo, the symbol of the Roman Empire, visually separating them. Montesquieu's idea of the separation of church and state is here expressed in paint.

Joseph's brain contained no trace of democratic thought, no idea of freedom or any sensitivity to human rights. When it suited him and the right idea popped into his head he was quite capable of trampling over his subjects' wishes or introducing barbaric punishments. From Joseph's point of view the money circulating in the country should be flowing through his administration, not into the coffers of the churches, those swamps of superstition and clerical mumbo-jumbo.

Historians use terms such as 'enlightened despot' to describe him and Frederick the Great, seemingly unaware of the irony in that oxymoron. It would be better to call them 'secular despots' – as opposed to Maria Theresia, for example, who was undeniably a 'religious despot' of the first chop.

She did, however, let her two golden boys go to Rome to give the Enlightenment project for secularisation a push in the right direction. And she, the Empress who hated the very thought of Protestants in her Catholic empire, paid Batoni to paint the manifesto of that project. She did not have an allegorical mind: she just saw a painting of her two beloved boys clasping hands in harmony.

Reception

We are not surprised that Batoni's stunning painting caused a sensation – when had its like been seen before? Consider the reaction during its three-day stop in the Ducal Palace in Florence on its way to Vienna.

The famous painting done in Rome by Batoni that shows an almost full figure view of Emperor Joseph II and the Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo arrived in Florence. It was put on public display for three successive days in an apartment of the Palazzo Vecchio. The painting aroused amazement and was judged to be a truly outstanding work.

…

On the last day of its exhibition the mass of people who wanted to see the painting was so great that attendants had to be posted in order to prevent a disorderly crush.[9]

Just imagine the impact that this portrait had on the brothers' contemporaries. You pass by other portraits with just a glance: the usual figures in landscapes, the family home in the background, the dogs, the children, the book or the other object pro memoria. And then you stand before this, the two pale brothers holding hands.

Batoni was not only extremely well paid for the original, he received many orders for copies not only from the court but from many other buyers. He was also ennobled and sent a number of valuable presents. All those years of painting portraits of passing aristocrats and their dogs standing in front of miscellaneous antiquities had paid off. The number of copies and the enthusiasm for this portrait show how highly it was regarded.

We Habsburg conspiracy theorists note with pleasure that the Pope, Clement XIV – the one Joseph had helped onto the papal throne and who had completed the deal by banning the Jesuits in 1773 – even commissioned a copy of Batoni's painting to be executed in mosaic by Bernardino Regoli of the Vatican's own mosaic workshop, which he sent to Maria Theresia as a gift in 1773, the year of the Jesuit ban. For the Habsburgs, this rather clunky copy was not just any old papal present: when the mosaic portrait arrived verses were commissioned in its honour and everyone associated with it – even the driver of the transport wagon – received gifts in accordance with their station.

The circle which Joseph and Leopold had started to draw in Rome in 1769 was completed when that mosaic arrived. And everyone at the Habsburg court knew it.

This was the image that the enlightened thinkers of the Empire had before them. Here were the golden lads shining in the surrounding darkness who would bring Austria out of its historical slumber using the rationality, the empircism of De l'esprit des loix.

It wouldn't last.

[A few small changes were made to this piece on 21.08.2016 to improve clarity and remove a few errors.]

References

- ^ I am aware that I have not always been completely precise about the exact titles of the Habsburg monarchs in this period, which covered the complicated period of the co-regency, but the titles used are accurate enough for the purpose of this article.

- ^ The painting discussed here is Batoni's original, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. A version was made by Batoni containing full length figures and some changes: Roma became explicitly Minerva/Athena, held an olive branch of peace not a globe, etc. This painting was lost or destroyed in World War II.

- ^ Pezzl, Johann, Lebensbeschreibung Josephs II, Wien, 1790, p. 289.

- ^ 'Table des choses a voire' in Joseph's hand: AT-OeStA/HHStA HausA Hofreisen 1 Reisen Kaiser Joseph II., 1766-1781

- ^ Pezzl, p. 23.

-

^

Pezzl, p. 22.

The journeys that he undertook were always made with the greatest simplicity. A general or other high-ranking officer, a couple of cabinet secretaries, a few servants, all in three or four carriages, made up the full party. -

^

Pezzl, p. 22f.

The roads he drove along were filled with with people and everywhere could be heard the joyful cry: 'Long live the Emperor!'. Deputies and a guard of honour were sent to him. He forbade it all, saying that 'he was travelling incognito'. - ^ Immanuel Kant, 'Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?' (1783), in Schriften zur Anthropologie Geschichtsphilosophie Politik und Pädagogik, Darmstadt, 1966, p. 53.

-

^

Quoted in Schmitt-Vorster, Angelika, Pro Deo et Populo: Die Porträts Josephs II. (1765-1790), Untersuchungen zu Bestand, Ikonographie und Verbreitung des Kaiserbildnisses im Zeitalter der Aufklärung. Dissertation LMU München: Faculty of History and the Arts.

This work has been plundered shamelessly at points in the creation of the present post. Her work is indispensable for those who wish to trace the many versions of the painting and its influence on the representation of Joseph in other works.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!