The Schubert trajectory

Posted by Richard on UTC 2016-11-04 19:11

Standing back

How difficult it is, in the midst of the turmoil of a life, to see and understand its greater context and significance! To do this we have to stand aside from the churning clockwork in which we live, step out of the comfortable contexts in which we normally think and assume the role of the impartial visitor from outer space. Who of us can do that? Ordinary minds are tethered to their present.

When it's all over, the biographer collects the accumulated scraps and snapshots of a life as seen from within: positions filled, marriages, friendships, antipathies, letters written and received and all the numerous events of the quotidien. The lives of the great, the important and the busy are buried under such detail. In contrast, the lives of social nonentities such as Schubert leave relatively little behind.

The greatest challenge of biography is not to collect all these artefacts and lay them out accurately over a few hundred pages but to transcend the more or less bountiful paperwork of the everyday and achieve the alien's perspective on the life lived. The details make no sense, irrespective of how many of them there are, without the greater understanding of the trajectory as a whole.

In our next few Schubert posts we are going to be looking at some of the more interesting of his contemporaries, but before we splatter you with Schubert-trivia and detail we wanted to set down an overview of the trajectory of Schubert's life. Once this context is clear the details will start to make more sense to us.

The trajectory of a life

When Schubert's life ended, at 3 pm on 19 November 1828, he was 31 years old. What had the trajectory of that life been? What would he have seen had he been able to turn around and look impartially at that trajectory?

Franz Grillparzer (1791-1872), whom we met a year ago as the author of the text for the wonderful Zögernd leise, wrote the epitaph on Schubert's life for his gravestone: 'The musical arts have buried here a rich possession, but many even more beautiful hopes'. That epitaph has often been criticised as misunderstanding or downplaying the importance of the composer: Schubert achieved greatness in his 30 years on the Earth, more greatness than most, more years were not needed to confirm that. But Grillparzer's epitaph was totally accurate and Schubert's most loyal friend, the conscientious and measured Joseph von Spaun (1788-1865), shared that view. They saw that trajectory in a calm, analytical light, both of them, who had known him so well.

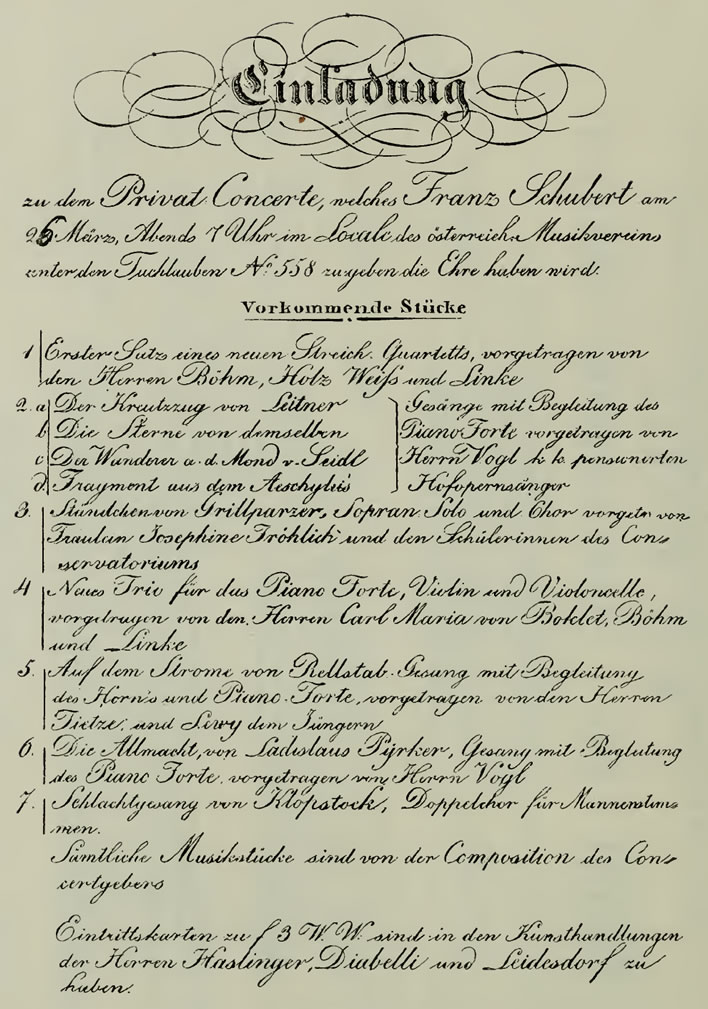

At the moment of his death Schubert had barely 'achieved' anything. All his work on operas had come to nothing, mostly blocked by censorship. He had given one public concert eight months previously. One. The Vienna Society of the Friends of Music had held several concerts featuring his works.

The programme for Schubert's one and only concert, 26 March 1828.

At that moment on 19 November 1828 he left some old clothes, some loose change and some 'old music scores' that were valued nominally at 10 Gulden. In the final accounts, the financial cross-section of the life that stopped on 19 November, the costs of his last weeks of medical care and his burial were not covered by his assets. He died broke, in other words. He had no wife, no children and no close female friend. He had been cared for by his brother's 13 year-old daughter.

The family covered the deficit, but immediately started to cash in on what remained, beginning with the sale in December of the confected 'cycle' Schwanengesang, which brought them in 300 Gulden. Another 2,000 Gulden flowed in from the sale of some instrumental works a year later. You simply can't beat the death of a composer to shift sheet music.

In contrast, most of the people of his Freundeskreise, his 'Circles of Friends', most of the participants in the Schubertiaden, presumably had careers, married and founded families. At their deaths most, we presume, left money, belongings, grieving children and sufficient assets to care for them. Schubert left his socks, a few shirts and a couple of old coats. And that was the end of him.

The professional struggle

Ernst Hilmar (1938-), the Austrian musicologist and archivist, argued that Schubert was, in reality, 'a very successful composer'. Otto Deutsch (1883-1967), the great Schubert scholar, noted that Schubert 'had never gone hungry'. Perhaps these statements are strictly speaking true, considering all we now know about his genius, but leaving behind a few old clothes after your lonely death does not bring the word 'successful' to mind. Nor does avoiding starvation.

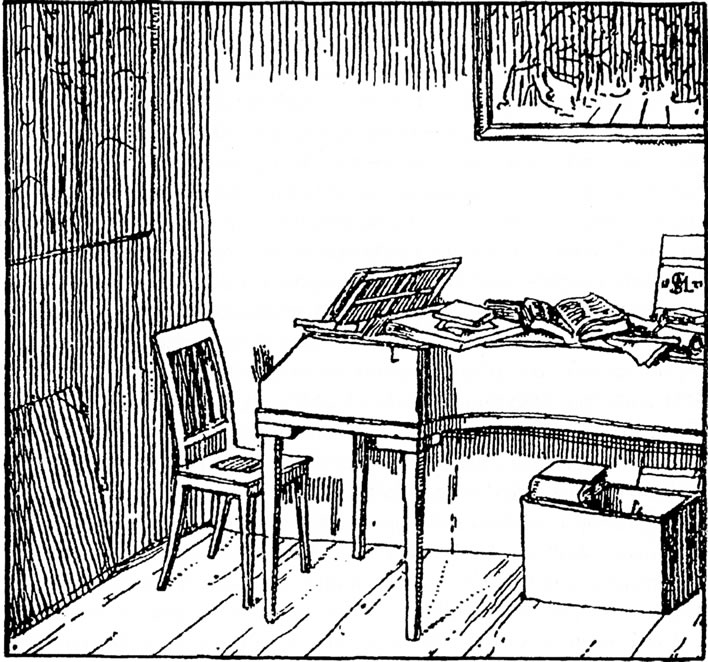

Moritz von Schwind: The successful composer's room in Wipplinger Strasse, 1821.

At Schubert's death he still had an outstanding loan from Franz von Schober (1796-1882) for just over 190 Gulden: the 'successful composer' was surviving on borrowed money right up to the end. Schober, by the way, was paid back by the executors of Schubert's estate by end of that year. Hilmar, in fact, goes on seemingly unwittingly to support my position. At that moment of caesura, 28 November, 1828:

Not one symphony, only one string quartet (D 804) out of 15 complete ones, one Mass (D 452) out of eight complete ones and only three piano sonatas (D 845, D 850, D 894) from more than a dozen such works had been published.

Music publishers, writes Hilmar, were not interested in such wares. In that case his labours didn't do him any good at all. Schubert's professional life was spent battering his head against brick walls and coping with repeated rebuffs, rejections and disappointments. In this respect we pointed out that 1823, the year of the composition of Die Schöne Müllerin, 'was a year of work without profit, of setbacks and rejection, disease, pain and hopelessness'. Nothing really would change much over the next five years, either.

The art of forgetting

Only a very few of his friends were really aware of his epochal musical status. Grillparzer, the Spauns and a few others understood his importance. For most of his acquaintances the death of Schubert was merely the end of one aspect of a particular era of life in 'Old Vienna'. Many would have attended the Schubertiaden or the other intimate performances in which he participated. For them, Schubert was just a figure in a flowing, paperless present: he was there amongst them and then, after that November day, he was gone.

The Strauss and Lanner dynasties were now carrying the torch of 'Old Vienna', happy Vienna, dancing Vienna and the decaying Empire. Schubert's most loyal and devoted friends, above all Joseph von Spaun, wrote fitting obituaries. A gravestone was commissioned, the gravestone on which Grillparzer's epitaph for him was written. It was erected in the summer of 1830. After that, that was it. He was gone.

He remained in the hearts of a few, but in the circles of the Schubertiaden and the salons he was forgotten. In her memories of those times written in the 1840s, around 15 years after Schubert's death, the author and socialite Caroline Pichler (1769-1843) barely mentions him. She was not musically inclined and so Haydn (1732-1809), Beethoven (1770-1827) and Schubert get a few sentences each in a large two-volume work. Gossipy as ever, for Schubert she simply repeats Vogl's nonsensical anecdote of Schubert composing 'in a trance' out of which the music simply flowed without effort. She had really nothing to say about him apart from a piece of third-hand tittle-tattle. She does not note his death or funeral: it had no meaning for her.

For most of Vienna, at least those people who had even heard of him, Schubert had just been a passing phenomenon. His music was hardly published, scraps of manuscripts accumulated in drawers throughout Vienna and Germany. By the beginning of 1829 Schubert had gone and it would be more than another 20 years before anyone tried to remember him or rediscover who this 'Franz Schubert' was.

Tellingly, this rediscovery was not initiated by any of these 'friends' from the famed 'circles'. It was Franz Liszt (1811-1886) and Robert Schumann (1810-1856) and Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) who started the process – that is, it was a musical resurrection: Schubert was reborn through the quality of his music. After that, some biographers attempted the rediscovery of the life. The first one of these biographies (Kreißle's) appeared more than 37 years after that winter day in 1828. For a hundred years after his death people were still finding manuscript scores in drawers and tucked into books.

The art of melancholy

That is the trajectory of Schubert's life. Was Schubert himself aware of it? How can we know? He was capable of gaiety – the one-man social entertainer has to be – but the underlying tenor seems to have been melancholy.

The modern modish word 'depression' is not correct here. Schubert never seems to have evidenced the classical characteristics of the depressive's checklist: no listlessness, no apathy, no black moods or sleeplessness (that we know of). On the contrary, he was driven by an almost superhuman work-ethic. He never succumbed. But, in Die schöne Müllerin and the Winterreise, in the late trios and piano sonatas, we cannot fail to hear it. The roots of that melancholy are easy to find.

Franz Peter Schubert's grandfather, Carl Schubert, a Moravian farmer, had lifted up socially his two sons, Karl and Franz Theodor, through a Jesuit education. They in turn had lifted themselves up into the lower bourgoisie of the teaching profession. Franz Theodor's son, Franz Peter had gained an education on the basis of his musical skills, but after that, there was nowhere for him to go. He had no fixed position and thus no fixed income.

The ridiculous and authoritarian Ehe-Consens Gesetz, 'Marriage Approval Law', introduced 16 March 1815, required that the lower orders apply for a special permit to marry: without a demonstrable income sufficient for the upkeep of a family, or ownership of property, there was no hope that they would attain a permit. It was supposed to improve morals, family life and childcare, but, like most of the other top-down, authoritarian, Catholic-Austrian wheezes it did the opposite.

Vienna was the prostitution capital of Europe. Young men and women with no hope of a marriage and family life were everywhere. Schubert was one of them and the great disaster of his life occurred in September 1816, the year after the law had come into effect. His application for a job in Laibach had been turned down on 7 September. The day after that he confided in one of the only six entries in his only diary the alternatives he now had: a dreary life without female companionship or a life of 'coarse sensuality', that is, the recourse to prostitution. Cohabitation without benefit of marriage could be – was – punished by imprisonment and no sensible woman would go down that path. Even had he remained the humble teaching assistant his father so desired – in the family firm as it were – he would have still not qualified for a marriage permit.

His secret passion for Therese Grob went unfulfilled. The painfully introverted Schubert never told her of his love and simply bottled it up within himself. How could he even declare a love for which there could be no legal outcome? He had to watch her marry a master baker – someone with status, particularly among the sugar and cake fetishists of Vienna – and rise to comfortable prosperity. She would be an old lady before she learned of the passion Schubert had secretly felt for her. For her he had just been a friend of the family.

The song album which Schubert is supposed to have put together for her on the occasion of her 18th birthday on 16 November 1816 – only two months after that dark night of the soul expressed in his diary – is part of the Schubert love-story myth: he never actually gave it to her personally, just handed it over to her brother Heinrich. His hopes of Therese had been dashed the year before by that damn Ehe-Consens Gesetz. If there had been any lingering doubts, which seems unlikely, they were definitively obliterated when she married her baker in 1819.

He wanted sex, true, but he wanted love and affection much more. During his twenties Schubert had loves, but all unrequited. Some of his aspirations, such as Caroline Esterházy in 1824, were hopelessly out of reach, mere fantasy; others, such as Pepi Pöcklhofer in 1818, fizzled out for some reason. There may have been more, Schubert was by no means a monk, but we know nothing about them and they certainly didn't come to anything.

Not many years after this diary entry, around 1822, a moment of 'coarse sensuality' would lead to the syphilis that plagued him through his twenties and made him a sexual untouchable. We can understand why so many of his friends speak of an underlying melancholy.

Social insecurity

His psyche really had a lot to cope with. We have already discussed Schubert's low social status and lack of recognition: the musical entertainer at soirées; the piano-player at song recitals, when all attention was directed to the singer; his invented position that never fitted into the rigid hierarchy of the Empire – 'Compositeur'; his friends were almost all minor nobility – they could go places and do things that he couldn't; as far as the Viennese police were concerned when they encountered him in the Senn case, he was a 'teaching assistant' – a very short step away from a complete nonentity.

He was short, pot-bellied, short-necked, his face far from handsome and he carried the stains and smells of too much smoking of inferior tobacco. He was painfully short-sighted – 'painfully' here is precisely used, since it was probably his bad eyesight and not syphilis that is the easiest explanation of the crashing headaches that so often beset him and through which he continued to work heroically. He was not entirely careless of his appearance, he had, for the time, a remarkable set of intact teeth, but the basics were just not there.

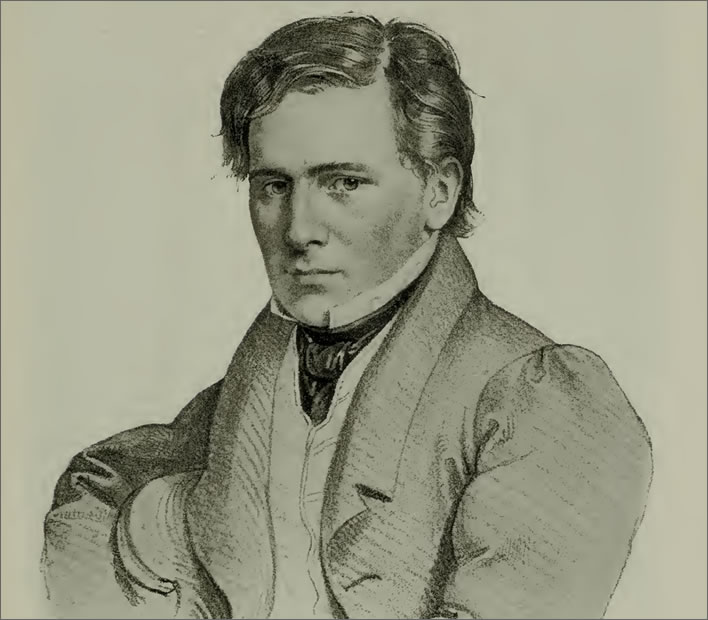

On this blog we consistently use Friedrich Lieder's (1780-1859) sketch of him because of its unflattering honesty. Most of the other representations of him are hopelessly 'improved' – which is what was expected of the portrait artists of the time.

Friedrich Lieder's 1827 sketch of Schubert: spontaneous, without cosmetic improvements.

Schober's viciously entertaining caricature of dumpy little Schubert, spectacled and with a carefully delineated pot-belly, trotting behind the singer Michael Vogl (1768-1840), that man-mountain, must have been deeply wounding if he ever got to see it. Possibly not, we do not know: it was found among Schober's carefully hamstered papers. It may have been done for the delectation of Vogl, whom Schober had introduced to Schubert.

Schober's caricature of Schubert and Vogl 'setting out to battle and victory'.

Schubert participated in the Unsinnsgesellschaft, the 'Nonsense Society', a secretive clique of young people who met up in pursuit of entertainment and diversion. Jokey manuscripts full of nicknames, double meanings and humorous and suggestive drawings were produced and passed from hand to hand, an extremely risky activity given the censorship and repression of the times. Schubert had to put up with his fair share of mockery.

Exploitation

Returning to our consideration of the trajectory of Schubert's life, it was Schober who set him on the path of salon entertainer. He invented the Schubertiade, at which his little friend Schubert and often his big friend Vogl would turn up and entertain the assembled 'friends' (without the 'stiff people') for free. These meetings gave Schubert a limited audience – the contents of a large drawing room – and the adoration of his musical skills may have been good for his morale, but when we aliens stand back and look at these events from a distance we must ask the grumpy but always relevant question: cui bono?, for whose good?

Schober's.

It was he who named these events Schubertiaden, thus binding the composer to them for the rest of his life. This was not branding, this was enslavement.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Franz von Schober, 1821. Let's play the Jane Austen game: this person could be Mr Darcy? No. Mr Bingley? No. Mr Collins? God, no. Mr Wickham. Yes, quite. Lock up your daughters.

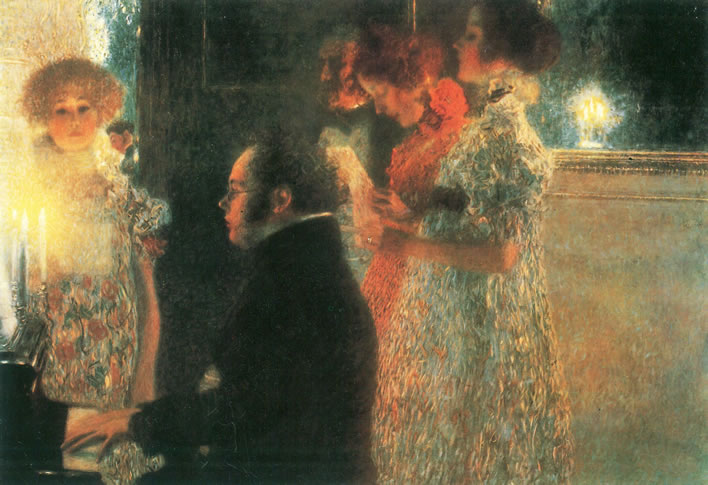

It was said of Schober later that he was adept at using the talents of others to his own parasitic benefit and for the purposes of his own promotion. After Schubert's death he would attach himself to Liszt. As organizer of the Schubertiade he had a key role, made contacts among youthful, intellectual society and had a chance to meet and, hopefully, to seduce women. In the famed Schubertiade portrait by Moritz Schwind (1804-1871), Schubert is playing, Vogl is singing and Schober is in the second row flirting with a woman. In later years Schwind fell out viciously with his former friend Schober, and for those who have eyes to see this portrait from 1868 is perfectly clear in its message about him.

Moritz von Schwind's homage to a Schubertiade. This was drawn in 1868, 40 years after Schubert had died, and is therefore not a portrait of any particular event but more of a group portrait of the people in Schubert's life.

In the second row on the right of the picture Franz von Schober is flirting with Justina von Bruchmann. They are the only ones not listening to the performance. Schwind is reminding us that Schober entered into a secret engagement with Justina (whose father was probably the richest man in Vienna). This plan was discovered and the engagement dissolved in 1823, leading to a break between Schober and her brother Franz von Bruchmann, a leading figure in the Schubert circles. By the time he created this group portrait Schwind had himself developed a deep loathing for Schober, a loathing that is unmistakeably revealed. Revenge is a dish that needs to cool for 40 years before it is eaten.

Josef Kriehuber, Portrait of Moritz von Schwind, 1827.

In Schwind's scene the singer is Michael Vogl, whom Schubert biographers routinely praise for getting the young composer an audience. He was from all accounts a pompous egomaniac, who, after some prompting, recognized Schubert's talent, but more likely recognized Schubert's potential in providing the fading opera star with a new career as a Lied-singer. Cui bono? Schober and his friend Vogl both got their piece of Schubert, as we say nowadays.

Leopold Kupelwieser, Portrait of Johann Michael Vogl, 1821.

Some – among them Joseph von Spaun – have asserted that the Schubertiaden were essential to Schubert's development, a kind of cultural and moral life support system for that most Viennese of composers. Your grumpy forensic biographer must assert that in his opinion they were not – they were in fact 'just another brick in the wall' for the composer: they brought him no money and the limited acquaintance of the members of a salon culture. 'What of soul was left, I wonder, when the kissing had to stop?' wrote Browning of the Venetian courts of pleasure and their musical entertainer Baldassare Galuppi. The Viennese salons of pleasure, the Schubertiaden, were just as evanescent: when their eponymous performer died that November in 1828 they ceased, leaving nothing behind.

In contrast, Schubert's first real concert a few months before he died brought him in a substantial amount, a wider audience than a Schubertiade could ever achieve and reviews of the concert that appeared throughout Europe. If only, we mutter, if only.

The Schubertiade were fundamentally selfish events – they kept their house musician busy entertaining their guests, paid him nothing, gave him a buffet and some drink and kept the knowledge of his talent as a composer, his genius and fame, firmly bottled up in the febrile, self-regarding scene of the Viennese salon. The typical conclusion of Schubert's salon appearances was a buffet, some drinking and then some dancing, as Schubert, the resident piano-player, would be expected to knock out gallops and ecossaises into the early hours of the morning.

The Schubertiade became part of the romantic mythmaking of the Schubert biography as much as the Freundeskreise and the Biedermeier. Those who subscribe to that myth cannot resist the Austrian Gustav Klimt's (1862-1918) elevation of the glittering romance of the events: the slender, blank-faced, dead-eyed girl (Marie Zimmermann, one of Klimt's mistresses); the distinguished-looking aristocrat lurking in the shadows and, in the foreground, the golden composer, wasting his time amusing these parasites. We would like to think that Klimt was making some incisive comment, but we fear he was just literally gilding the myth, painting some nice frocks and his girlfriend.

Gustav Klimt, Schubert am Klavier, 1898 (destroyed 1945)

Money

And when we stand far enough back from Schubert's trajectory, so far that its details all fade, there is one thing we still see: money – or rather the lack of it. Most of the other composers of the time had position, or money, or both.

The most egregious example is surely Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847). His family was extremely rich and indulged their prodigy: he was dandled on Goethe's knee, travelled around Europe giving concerts, had an orchestra to do his bidding, founded a singing school and founded a family. His work was printed and sold well across the continent.

In contrast, Schubert's family had no money; they could only enslave him as a teaching assistant; Goethe never bothered to respond to his letters and music; Schubert never travelled outside Austria, so no concerts in the capitals of Europe for him, his only concert was the one that took place a few months before his death; unlike Haydn or Beethoven no great princes supported him; he kept a small group of Viennese parasites entertained; a small amount of his music was grudgingly published, but large amounts were borrowed and disappeared into someone's drawer or library; he lived alone in rooms in friends' apartments without wife or family; he left nothing. The single difference? Money. Yet Schubert, the productive melancholic, left a legacy that is greater than Mendelssohn's (at least in my opinion). Unlike Mendelssohn, however, Schubert's life brought him no benefit. No benefit at all.

We look back on that trajectory which ended on 28 November 1828 with great melancholy but with great astonishment at what Schubert achieved despite all that.

Coming soon

Our next piece of Schubertiana will deal with Schubert's friend, Franz von Schober, one of the great conundrums of Schubert studies.

0 Comments UTC Loaded:

Input rules for comments: No HTML, no images. Comments can be nested to a depth of eight. Surround a long quotation with curly braces: {blockquote}. Well-formed URLs will be rendered as links automatically. Do not click on links unless you are confident that they are safe. You have been warned!